A world beyond passwords: Improving security, efficiency, and user experience in digital transformation has been saved

A world beyond passwords: Improving security, efficiency, and user experience in digital transformation Deloitte Review issue 19

26 July 2016

There’s a reason why so many of us use the same simple password for every login: Who can remember dozens of different combinations of numbers and letters? The good news is that technology is on the verge of rendering passwords obsolete, bolstering security as well as making users and customers happier.

The next time you’re at your computer about to access sensitive financial information about, say, an acquisition, imagine if you didn’t have to begin by remembering the password you created weeks ago for this particular site: capitals, lowercase, numerals, special characters, and so on. Instead of demanding that you type in a username and password, the site asks where you had lunch yesterday; at the same time, your smart watch validates your unique heart-rate signature. The process not only provides a better user experience—it is more secure. Using unique information about you, this approach is more capable and robust than a password system of discerning how likely it is that you are who you claim to be.

The next time you’re at your computer about to access sensitive financial information about, say, an acquisition, imagine if you didn’t have to begin by remembering the password you created weeks ago for this particular site: capitals, lowercase, numerals, special characters, and so on. Instead of demanding that you type in a username and password, the site asks where you had lunch yesterday; at the same time, your smart watch validates your unique heart-rate signature. The process not only provides a better user experience—it is more secure. Using unique information about you, this approach is more capable and robust than a password system of discerning how likely it is that you are who you claim to be.

Digital transformation is a cornerstone of most enterprise strategies today, with user experience at the heart of the design philosophy driving that transformation. But most user experiences—for customers, business partners, frontline employees, and executives—begin with a transaction that’s both annoying and, in terms of security, one of the weakest links. In fact, weak or stolen passwords are a root cause of more than three-quarters of corporate cyberattacks,1 and as every reader likely knows, corporate cyber breaches often cost many millions of dollars in technology, legal, and public relations expenses—and much more after counting less tangible but more damaging hits to reputation or credit ratings, loss of contracts, and other costs.2 Shoring up password vulnerability would likely significantly lower corporate cyber risk—not to mention boost user productivity, add the goodwill of grateful customers, and reduce the system administration expense of routinely managing employees’ forgotten passwords and lockouts.

Learn More

View the Dbriefs webcast

Explore the Cyber Risk Management collection

Read Deloitte Review

The good news, for CIOs as well as those weary of memorizing ever-longer passwords, is that new technologies—biometrics, user analytics, Internet of Things applications, and more—offer companies the opportunity to design a fresh paradigm based on bilateral trust, user experience, and improved system security. Successful execution can help both accelerate the business and differentiate it in the marketplace.

In fact, the ability to access digital information securely without the need of a username and password represents a long-overdue upgrade to work and life. Passwords lack the scalability required to offer users the full digital experience that they expect. Specifically, they lack the scalability to support the myriad of online applications being used today, and they do not offer the smoothness of user experience that users have increasingly come to expect and demand. Inevitably, beleaguered users ignore recommendations3 and use the same password over and over, compounding the vulnerability of every system they enter. Perhaps even more important, passwords lack the scalability to provide an authentication response that is tailored to the transaction value; in other words, strong password systems that require unwieldy policies on character use and password length leave system administrators unable to assess the strength of any given password. Without such knowledge, enterprises struggle to make informed risk-based decisions on how to layer passwords with other authentication factors.

The 21st century meets human limits

Twenty years ago, a typical consumer had only one password, for email, and it was likely the same four-digit number as his or her bank account PIN. Today, online users create a new account every few days, it seems, each requiring a complex password: to access corporate information, purchase socks, pay utility bills, check investments, register to run a 10K, or simply log into a work email system. By 2020, some predict, each user will have 200 online accounts, each requiring a unique password.4 According to a recent survey, 46 percent of respondents already have 10 or more passwords.5

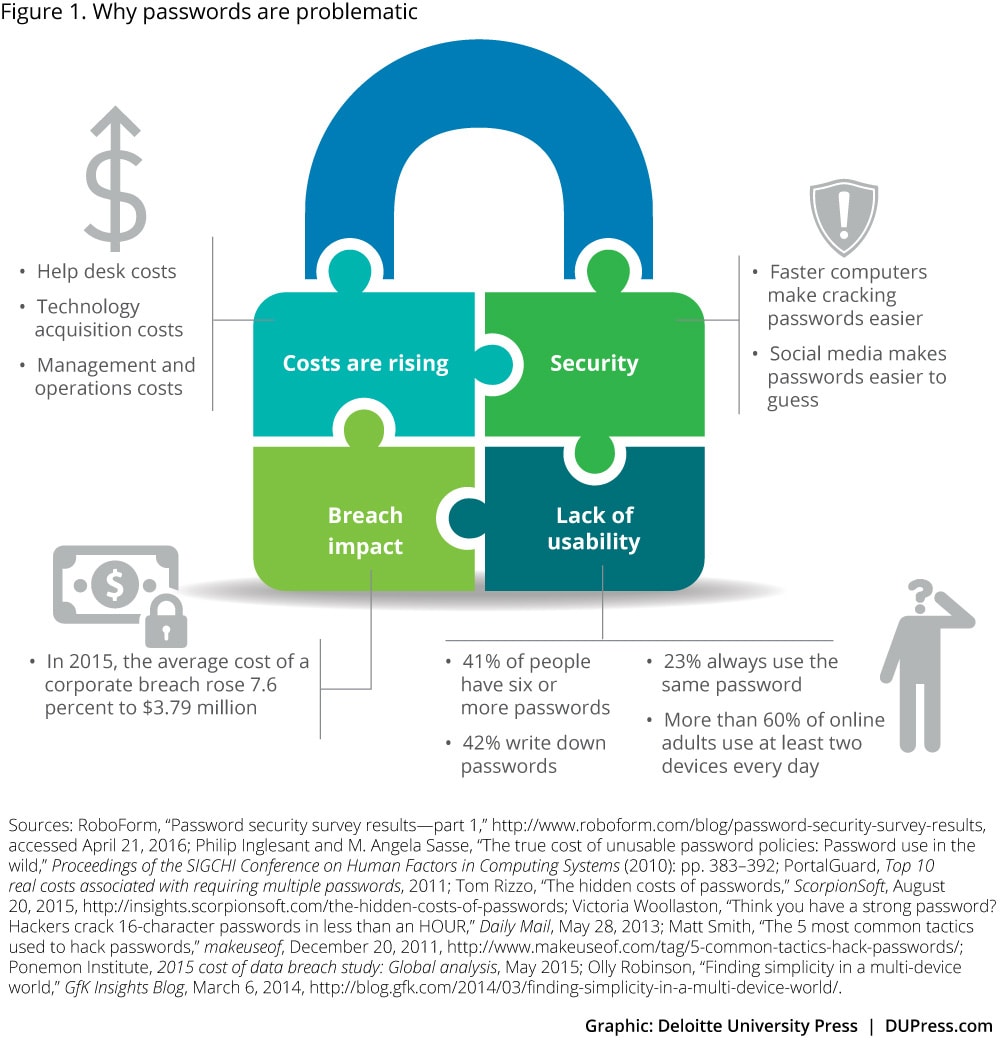

And the demands of password security are running into the limits of human capabilities, as shown in figure 1. According to psychologist George Miller, humans are best at remembering numbers of seven digits, plus or minus two.6 In an era where an eight-character password would take a high-powered attacker 77 days to crack, a policy requiring a password change every 90 days would mean a nine-character password would be sufficiently safe.7 But such a long password—especially when it’s one of many and changes regularly—starts straining people’s memory. The inevitable result: People reuse the same weak passwords for multiple accounts, affix sticky notes to their computer monitors, share passwords, and frequently lean on sites’ forgotten-password function. In a recent survey of US and UK users, 23 percent admitted to always using the same password, with 42 percent writing down passwords. While 74 percent log into six or more websites or applications a day, only 41 percent use six or more unique passwords.8 According to another survey, more than 20 percent of users routinely share passwords, and 56 percent reuse passwords across personal and corporate accounts.9 Password management software partially alleviates this particular issue, but it is still ultimately tied to the password construct.10

Even if an employee follows all regulations and has six distinct strong passwords that they remember, they still may be vulnerable. Humans can still be bugged or tricked into revealing their passwords. There is malware, or malicious software installed on computers; there is phishing, in which cyber crooks grab login, credit card, and other data in the guise of legitimate-seeming websites or apps; and there are even “zero day” attacks, in which hackers exploit overlooked software vulnerabilities.11And of course, old-fashioned human attacks persist, including shoulder-surfing to observe users typing in their passwords, dumpster-diving to find discarded password information, impersonating authority figures to extract passwords from subordinates, discerning information about the individual from social media sources to change their password, and employees selling corporate passwords.

No wonder the operational costs of maintaining passwords, including help-desk expenses for those who forget passwords, and productivity losses because of too-many-attempts lockouts and other issues are rising. Even more worrisome, ever-increasing computing power is enabling new brute-force attacks to simply guess passwords. The future of the password is both expensive and fraught.

- 74 percent of surveyed web users log into six or more websites or applications a day12

- 20 percent of surveyed employees routinely share passwords13

- 56 percent of surveyed employees reuse passwords across personal and corporate accounts14

From geolocation to biometrics

Corporate leaders are well aware that information and access strategy is at the core of nearly every business today. It’s time to recognize also that the password—the mechanism used historically to implement this strategy—is fundamentally broken. Given their fiduciary and governance responsibilities, boards of directors and C-suite executives owe it to stakeholders to guard the corporate treasure chest—digital information—by providing more robust online access protections. In turn, investors, customers, employees, partners, third-party vendors, and others will benefit from stronger protection of corporate data coupled with easier access for legitimate users, thus bolstering the bilateral trust that is at the heart of any healthy business relationship.

From ancient Greece to the digital age

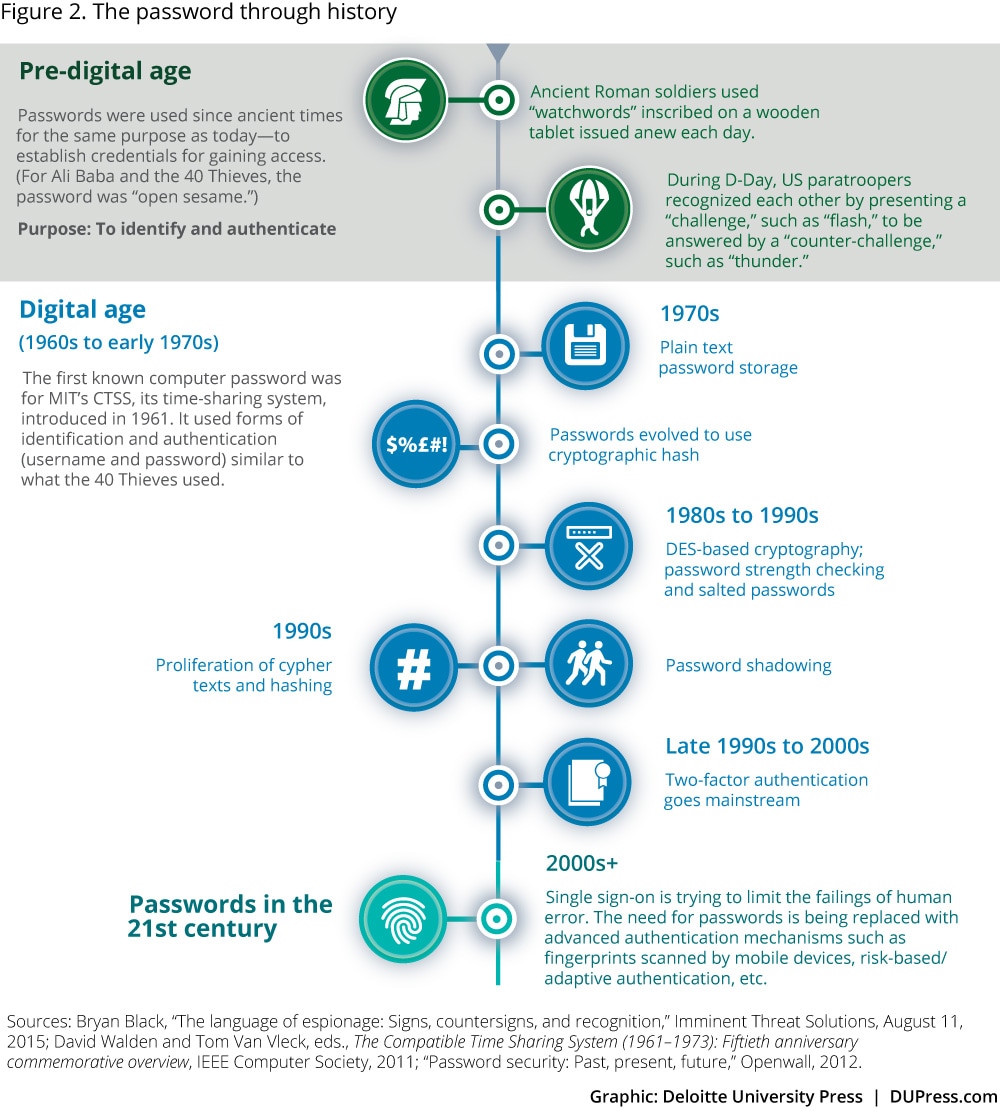

Passwords have been in use since ancient times for the same purpose as today: to establish one’s credentials to access protected assets. Establishing authority in this way depends on presenting “something you know”—the password—to be “authenticated” against the registered value. As figure 2 shows, passwords have been a cornerstone of our history, including serving as a digital key for around the past 50 years. Indeed, digital passwords used to possess advantages: They were simple, easy to use, and relatively convenient. They could be changed, if compromised. Conveniently, they could be shared, though this practice compromises security. Because passwords are the prevailing standard, corporate policies governing them are well established, and identity and access management systems support them.

Increasingly, consumers, employees, and partners all expect seamless digital interactions, leading to a fundamental paradigm shift in how companies help conceive, use, and manage identities. Supporting the makeover, new login credentials might include not just “what you know” or a specific password but also “who you are” and “what you have,” along with “where you are” and “what you are doing.” They can include detection of personal patterns for accessing certain information by time of day and day of week, other dynamic and contextual evaluations of users’ behavioral characteristics, individuals’ geolocations, biometrics, and tokens. Systems that rely upon authentication are evolving to become adaptive and can flag an authentication attempt as being too risky if typical usage patterns are not met—even though basic credentials may appear correct—and the system can then step up authentication, challenging the user to provide additional proof to verify his or her identity. Because of its ubiquity, the mobile phone is the most obvious device over which authentication takes place, but venture capitalists are also funding companies creating other connected devices, such as wristbands that identify one’s unique heartbeat and USB fobs that conduct machine-to-machine authentication without requiring a human to type in a passcode.15

Forces are converging for an overhaul. “From a technology perspective, we have amazing new authentication modalities besides passwords, and the computer capability to do the analysis to make informed decisions,” says Ian Glazer, management council vice chair of the Identity Ecosystem Steering Group, a private sector-led group working with the federal government to promote more secure digital authentication. “We’ve also overcome one of the biggest challenges: We put the authenticator platform in everyone’s hand in the form of a smartphone.”16

For companies, navigating change from legacy to new systems is never easy. But by following a risk-based approach, they can create a well-considered roadmap to make the switch by focusing investment and implementation on the highest-priority business operations. Beginning with a pilot to test selected options, companies can then expand successful solutions to where they are needed most. Most of all, setting out on the road to change soon is crucial. After all, businesses are operating at a time when continued innovation and growth depend more than ever on the integrity of information.

The new gatekeepers

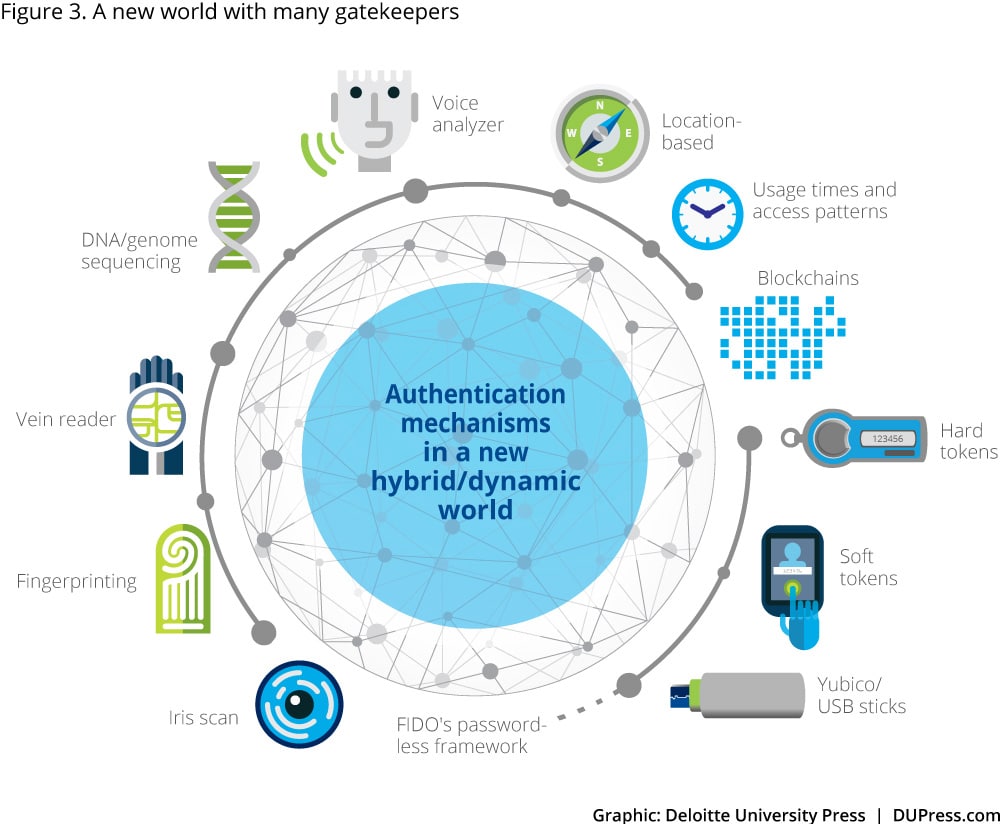

With the costs of password protection—in time, risk, and dollars—mounting, enterprises are looking to implement flexible risk-based approaches: requiring user authentication at a strength that is commensurate with the value of the transaction being requested. Fortunately, as shown in figure 3, various technologies are emerging that can be combined in a way that satisfies enterprise risk tolerance and user flexibility at the same time. Emerging technologies such as blockchain17 are positioned to replace the vulnerability of the single password with multiple factors.

Having multiple, cascaded gatekeepers fortifies security by requiring additional checkpoints. The more different proofs of identity required through separate routes, the more difficult it is for a thief to steal your identity or to impersonate you. Likewise, consumer platforms are paving the way by providing improved user experience by empowering consumers to choose how they access digital information.

The texting, sharing, and mobile-app economy has made immediate, seamless online communications and transactions ubiquitous. In a reversal of an earlier era, consumers are now the first adopters, followed by enterprises. Thus, as the smartphone becomes the consumers’ digital hub, on their person almost at all times, it is well positioned to perform a central function. Already, the majority of 16-to-24-year-olds view security as an annoying extra step before making an online payment and believe that biometric security would be faster and easier than passwords.18 Meeting these trends, leading technology companies founded the Fast IDentity Online Alliance in 2012 to advance new technical standards for new open, interoperable, and scalable online authentication systems without passwords.19

To maintain security and provide greater user convenience, a key precept in newly evolving login systems is multi-factor authentication. Gmail and Twitter, among others, today deploy this solution in simple form: They provide users a one-time code sent to their mobile phones to enter, in addition to the traditional password entered onto the user’s laptop screen. Enhanced security comes from authentication taking place over two devices owned by the user. A cyber thief would have to have access to the user’s phone, in addition to his or her online password, to get at the protected account.

For yet another layer of protection, in addition to delivery over different devices, the factors required for authentication can vary in type. In a two-factor authentication process, for example, a user could scan his or her retina via the camera on her laptop or smartphone, using biometric identification as a first step to gain access to his or her online bank account. In a second step, the bank could then send a challenge via text message to the user’s mobile phone, requiring the user to reply with a text message to finish the authentication.

One of the most popular new factors for authentication is biometric technologies, which require no memorization of complex combinations of letters, numbers, and symbols, much less which combination you used for which resource.20 It’s simply part of you—your fingerprint, voice, face, heartbeat, and even characteristic movements. Biometrics that can be captured by smartphone cameras and voice recorders will likely become most prevalent first, including fingerprint, iris, voice, and face recognition. Checking your biometric data against a trusted device that only you own—as opposed to a central repository—is emerging as the preferred approach. For example, you could use your fingerprint to access a particular resource on your own smartphone, which in turn sends its own unique device signature to the authentication mechanism that grants you access.21 This is the basis for scalability of authentication across multiple online services, and is the model that the Fast IDentity Online Alliance adopted.

A separate set of authentication factors come under the rubric of “what you have”—not only smartphones but perhaps security tokens carried by individuals, software-enabled tokens, or even an adaptation of blockchain databases used by bitcoin. Hardware USB keys enable workers to login by entering their username and password, followed by a random passcode generated by the fob at set intervals of time. Software tokens operate similarly, with a smartphone app, for example, generating the codes. Further off, the potential use of distributed blockchain technology could help provide a more secure and decentralized system for authentication.

Risk-based authorization in action

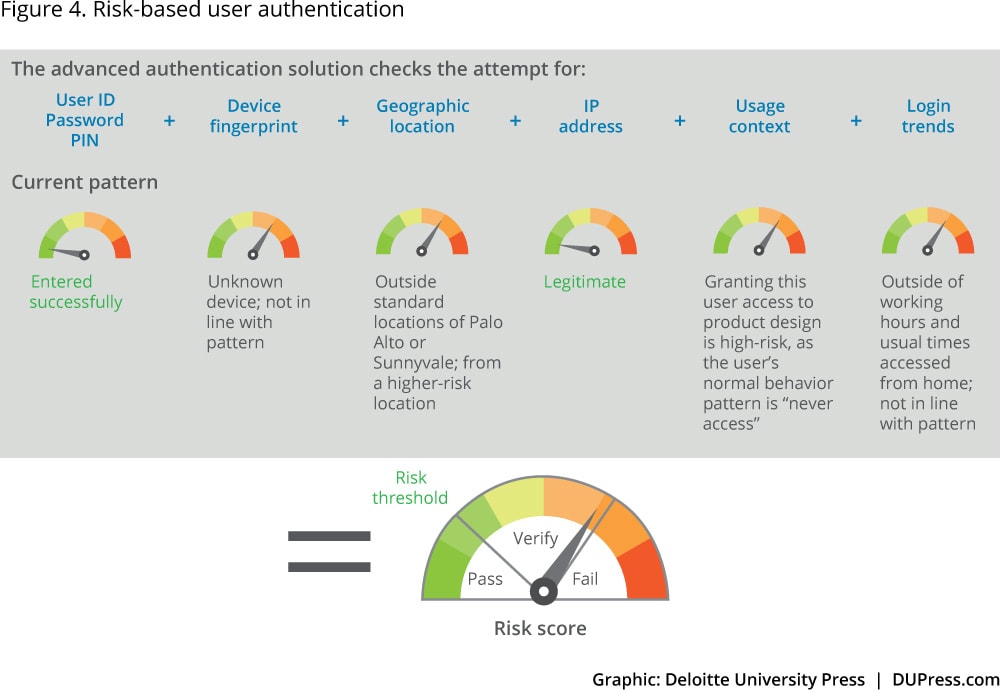

In a hypothetical example (figure 4), a corporate user usually logs in around 8:30 a.m. PST, logs out at 6 p.m., and logs in again around 9:30 p.m. Typically, he logs in from corporate offices in Palo Alto or Sunnyvale, accessing his company’s systems during the day via a company laptop or desktop.

On Monday, the user tries to log in from his Sunnyvale office at 11 a.m., using a work computer to access the corporate finance system. The user is logging in from a company computer from his office during his regular hours for information he typically accesses. The system grants access.

The next day, the user attempts to log in from Los Angeles International Airport at 7 p.m., using a company laptop to access the list of company holidays on an internal benefits system. Though his location and time are unusual, the other factors are typical for him, and the information is not sensitive. The system grants access.

The following day, a hacker tries to log in from Belarus at 3 a.m. with the user’s username and password to access designs for a not-yet-released company product on an internal development server. The username, password, and IP address are legitimate, but the other factors—such as location, time, and the information requested—are highly atypical for this user. The system implements controls that initiate step-up authentication techniques to verify the user’s identity—for instance, sending a one-time authentication code to the user’s phone. Because the hacker in this scenario does not have the user’s phone, he or she is unable to enter the authentication code, and the system denies access.

One of the most intriguing possibilities in new access controls is risk-based authorization, a dynamic system which grants access depending on the trustworthiness of the user requesting admission and the sensitivity of the information under protection. With Project Abacus, Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects is developing machine learning to authenticate users based on multiple assessments of their behavior.22 Using sensors such as the camera, accelerometer, and GPS functions, smartphones can gather a wide range of information about users, including typical facial expressions, their habitual geolocations, and how they type, walk, and talk. Together, these factors are 10 times safer than fingerprints and 100 times safer than four-digit PINs.23 With such capabilities, a user’s phone, or another device, can constantly calculate a trust score—a level of confidence—that the user is who he claims to be. If the system is in doubt, it would ask for more credentials through step-up authentication to verify the user’s identity or deny access altogether.

Such trust-scoring is useful for designing protections for information, depending on its sensitivity. Banking apps, for instance, would require very high trust scores; access to general news sites might require less. For widespread adoption of this approach, companies must take consumer privacy issues into account.

The best defense

To illustrate how a company might adopt a new system, take the hypothetical scenario of a retail chain that discovers the theft of customers’ credit card information. To fortify against future attack, the chain engages in a companywide assessment of its potential vulnerabilities and discovers three weaknesses that could have led to the attack: First, the server administration team keeps user names and passwords in an unencrypted text file on a shared directory. For convenience, store managers share their passwords for point-of-sale (POS) cash register systems with store associates to give them greater privileges to issue refunds, make exchanges, and the like. Last, to simplify integration, passwords for third-party vendors are set to never expire.

The retailer considers several new authentication options to strengthen security at points of sale, which analysis suggests were the most likely culprit in the breach. Managers decide against requiring employees to enter a one-time password delivered by smartphone each time they want to access the system because of the inconvenience. Instead, they opt to test—in one division of stores—a combination of fingerprint and facial recognition to authenticate store associates’ logins at POS systems. Not only is it more convenient for users, this option leverages existing infrastructure. Using cameras already in place to monitor POS activity, combined with a fingerprint-scanning application added to the login screen of touchscreen POS hardware, the company launches the pilot without additional hardware, spending primarily for third-party software development costs. The results: Store associates appreciate easier, faster logins; the company enforces the rights appropriate to a given user; and the constant reminder of the POS camera helps reduce theft among associates.

With the pilot’s success, the retailer implements the solution across all 1,500 stores, updating policies to further ensure security for the new system, including the application of fingerprint and facial authentication to higher-security operations with greater impact and safe recovery mechanisms for compromised authentication factors.

The company also engages in educational outreach to store associates. Local store trainers emphasize the new system’s ease of use, its effectiveness against vulnerabilities behind the original cyber theft, and the company’s willingness to invest in the latest technologies for the benefit of employees and customers. In addition, trainers share documents explaining how the solution works, with strong assurances that the biometric information captured will not be used for purposes other than POS authentication.

Not only security—digital transformation

Moving beyond passwords is not just a wave of the future—it makes economic sense today. A recent survey of US companies found that each employee loses, on average, $420 annually grappling with passwords.24 With 37 percent of those surveyed resetting their password more than 50 times per year, the losses in productivity alone can be staggering.25 When you factor in the cost of the support staff and help desks required, the savings from eliminating passwords alone—let alone the security advantages—may begin to more rapidly justify a transition. Plus, streamlining employees’ everyday tasks may improve employee happiness and productivity: Research into complaint departments in the United Kingdom found a correlation between process improvement and employee attitude and retention, and even variables as far afield as financial performance of the organization.26

True, abandoning a legacy password system—familiar, however irritating—and adopting new login methods may seem daunting for administrators, users, and customers. Any such migration requires a clear-eyed investment and implementation plan, aimed at overcoming very real challenges. First, from a technical perspective, no system is airtight. If smartphones or tokens are a linchpin, lost or stolen devices could introduce risk: As in the case of a lost credit card, a user would have to contact the issuer of the device or authentication authority to report the loss and get a replacement. Crooks sometimes use account recovery of lost authentication factors to hijack accounts.27 And mobile phones can be a weak link, since wireless communications are often unencrypted and can be stolen in transit.28

Even biometric technologies are not fail-safe—many are difficult to spoof but are not spoof-proof. Fingerprints, for instance, can be faked using modeling clay.29 System designers can address these potential vulnerabilities by implementing liveliness detection on sensors and storing the biometric information in an application-specific way, but these techniques are not ready to be fully implemented. Neither are most analytics-based systems, which won’t deliver a full slate of benefits without business process changes. For example, consider the reputation-based security system discussed in the sidebar “Risk-based authorization in action.” There, defenses examined not just the user ID attempting to access the system but also his location, time, behavior patterns, and the data he wished to access; in cases where these markers were unusual, the system denied access to sensitive business data. This is an excellent security approach but is predicated on an organization knowing and controlling all of its data: You can be aware if someone is trying to access sensitive data only if you have already classified that information as sensitive and determined its protocols for access.

Granted, moving beyond passwords may sound daunting, requiring major IT upgrades as well as changes to internal knowledge management and other business processes. But organizations can take incremental steps (figure 5) on the path toward a smooth transition. The following provides a roadmap:

- Prioritize. Assess strategic business priorities against the threat landscape and identify weaknesses in authentication systems for key business operations ranked by importance.

- Investigate. Examine possible solutions for stronger authentication, evaluating advantages and disadvantages in protecting against top threats and the ability to provide a practical, cost-effective, and scalable answer for the specific work environment. Standards-based authentication software solutions help to avoid the costs of new infrastructure and also to lay the groundwork for integration of next-generation solutions.

- Test drive. After choosing a promising solution(s), conduct a pilot in one or a few high-priority business operations. In these trials, collect data and feedback on users’ experience. Are users able to adopt the solutions easily and intuitively? Has easier online access made their work more efficient? Is online access then being used correctly more often in a way that provides greater security? Do users raise privacy or other concerns about any biometrics or adaptive, dynamic solutions based on their behavioral norms? From the online administrator’s perspective, what is the experience in the costs of maintaining the new system, compared with the old password system?

- Expand. Harnessing lessons from the pilot, apply the solution to a wider swath of key operations in phases based on prioritization.

- Revamp and educate. Update access policies. Replace policies on password security with risk-based policies for authentication based on the sensitivity of information requested. Teach users how the new system works, focusing on its advantages over the old technology.

Technological advances are giving organizations the opportunity to begin moving beyond passwords—and they should strongly consider taking that opportunity, especially as cyberthreats expand. Given password mechanisms’ poor user experience, rising costs, and security weaknesses, companies should look into migrating to new digital authentication systems that meet the twin objectives of tightening protection and improving user experience.

Organizations can begin their journey by starting to invest in non-password-based authentication solutions now as part of their digital transformation efforts, such as the rapid adoption of software-as-a-service platforms and omnichannel customer engagement initiatives. These new solution areas can serve as the foundation for broader enterprise authentication initiatives, which may take time. While we may have to live with passwords for some time given legacy platform constraints and technology limitations, there is no reason to delay the integration of non-password authentication initiatives. DR