AI-augmented cybersecurity How cognitive technologies can address the cyber workforce shortage

08 June 2017

As the cybersecurity talent shortage continues, adding cognitive technologies into the mix can help automate routine tasks, increase responsiveness, and allow cyber professionals to focus more on tasks requiring human ingenuity. Learn how it could work.

It may seem counterintuitive, but 0 percent unemployment in an industry is not a good thing. It’s often accompanied by high turnover, salary inflation, skill mismatches between workers and the positions they fill, and numerous vacant positions. Yet, this condition seems to be the reality for cybersecurity professionals, one of most consequential professions supporting an increasingly interconnected world. The demand for adequately trained and knowledgeable cyber personnel far exceeds the available talent pool.

Learn more

Subscribe to receive public sector content

Read Deloitte Review, issue 22

Create a custom PDF or download the issue

Recent reports confirm this situation to be true, and it’s unlikely to get better anytime soon: Cybersecurity unemployment is at 0 percent with more than 1.5 million job openings anticipated globally by 2019.1 Meanwhile, cyberthreats are increasing, and the annual cost of cybercrime is expected to rise from $3 trillion today to $6 trillion by 2021.2 This statistic is particularly troublesome news for government agencies responsible for protecting their citizens and corporations defending against crime. In an attempt to address this demand, federal and commercial marketplaces plan to spend $1 trillion globally on cybersecurity products and services between now and 2021.3

With no signs of the cyber workforce shortage letting up, new strategies should be devised to best utilize the available talent and meet public and private cybersecurity objectives. One of the most promising approaches is to combine cognitive technologies with cybersecurity professionals; this can address the myriad activities faced by the industry and ultimately aid in addressing the shortage of available talent. Through the use of advanced analytics, automation, and artificial intelligence, it’s possible to “train the technology” to deliver key insights that optimize cyber professionals’ work, streamline operational processes, and improve security outcomes. These efficiencies could permit a reallocation of cyber talent as well as the realignment of the tasks they perform, resulting in a more holistic approach to help mitigate the effects of a workforce shortage.

In an effort to challenge the traditional means in which cybersecurity is addressed, private and public organizations should rethink their approach toward talent and consider leveraging cognitive technologies to facilitate more cybersecurity insights in less time. Such an approach may enable a more secure cyber environment by taking targeted, proactive measures to prevent incidents before they happen.

All in a day’s work

Before tackling the cyber talent shortage, one basic question should be addressed: What do cybersecurity professionals do? The answer would seem to be straightforward enough, but the field has grown so large and complex that cybersecurity professional has often become a catch-all term that embodies a range of specializations, skills, and job functions. Some are experts with deep technical skills focusing on software development or digital forensics. Others specialize in the legal and administrative aspects of the profession, such as privacy, compliance, or customer service. And there are those practitioners who are self-taught, holding a number of certifications but with little “on-the-job” experience applying those skills. Just as each baseball position requires specific talents—pitchers and catchers are not interchangeable—cybersecurity professionals, too, often have different skills and responsibilities. These distinctions can be critically important in order to understand the quantity and quality of a cyber workforce.

To further complicate the issue, there is often great variability in how public and private organizations define cybersecurity and cyber-related skills. Some law enforcement agencies define cyber skills as active work—hacking into criminal organizations, tracking stolen credit card numbers, and determining the locations of criminally operated servers—as opposed to defensively operating firewalls and scanning the network for breaches, which many private-sector cybersecurity analysts perform on a day-to-day basis. Furthermore, an information security officer in one organization may be spending a lot of time on network administration and securing information sharing sites, while that same position at another organization is performing physical security work—or even law enforcement activity. These differing views of job responsibilities can lead to confusion when describing cybersecurity skills and shortages. Ultimately, they can result in a potential mismatch of resources to responsibilities, reducing professionals’ overall ability to provide the most impactful coverage of the cyber environment.

In a 2010 report, the Center for Strategic and International Studies highlighted the need to outline cybersecurity job descriptions and facilitate alignment across the industry. The study recommended that the US federal government should “sponsor an effort to create an initial taxonomy of cyber roles and skills,” ensure alignment between desired workforce skills and certification and licensing requirements, and develop a standard occupational classification for the cybersecurity workforce.4 To facilitate this approach, the report proposed job descriptions for a number of cyber roles that were eventually incorporated into executive guidance from the White House. It also encouraged the use of executive surveys, college graduate recruitment strategies, and legislation to identify and address workforce shortages.

An intelligence official noted that to be effective in cyberspace, the United States needs about 30,000 people with specialized security skills—it currently has 1,000.5 And the shortage extends beyond highly technical talent; it includes those with niche skills who can write secure code, design secure network architectures, and develop software tools for network defense and reconstitution following an event.6

In partial response to these recommendations and the clear need for specific cyber talent, the National Institute of Standards and Technology created a working group, the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE), to help set standards that categorize and describe cybersecurity work. Titled the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, it maps skills to 7 categories, 33 specialty areas, and 52 work roles.7 With common terminology, it can be much easier to identify and communicate exactly which skills are in short supply, which specialties can best leverage insights from cognitive systems, and which tasks can be automated.

The characterization of cybersecurity jobs can play an important role in helping an organization identify and devise tailored technological solutions to address the workforce shortage. For example, some of the defined duties of a secure network administrator are typically to identify security weaknesses in network architectures, divert unwanted traffic, and characterize expected network behavior—all tasks that can benefit tremendously from insights derived from data analytics and automation. Whether helping threat analysts monitor anomalous traffic, security auditors scan wireless connections, or network engineers block malicious packets, cognitive technologies can be leveraged to help reshape the existing talent’s workload. Once a sound understanding is gained of all the activities carried out by cybersecurity professionals, it is much easier to determine which can be addressed by cognitive systems, which require human talent, and how much of the workforce shortage can be addressed.

Ultimately, while there are commonalities, every organization and government agency is unique in its needs and resources. There is no one-size-fits-all solution that will address the talent challenges across sectors, regions, and positions. Thus, in order to grasp the specific effects the talent shortage is having, each organization should craft an accurate picture of the responsibilities and tasks assigned to each of its cybersecurity positions. With this information in hand, it can begin exploring how cognitive technologies can address the shortage.

Racing with the machine

Skilled cybersecurity personnel across the spectrum of roles are typically highly prized, practicing what is more of an art than an exact science. And they, perhaps better than anyone else, understand the state of the profession. Recent studies show that 82 percent of cybersecurity professionals from eight different countries report a shortage of cybersecurity skills; 71 percent believe this shortage does direct and measurable damage; and 76 percent believe there isn’t enough investment in cybersecurity talent.8

Cybersecurity professionals agree: Nine out of ten believe that technology could help compensate for skill shortages, and that “the solutions most likely to be outsourced are ones that lend themselves to automation” and other cognitive technologies.9 Here again, a framework to define and categorize skills can be useful. In identifying the work roles that are best suited to technological solutions and those where cognitive technologies can support faster, smarter human decision making, the cyber talent shortage can be addressed—or at least the gap may be minimized.

The role for cognitive technologies

So what exactly are cognitive technologies and how might they address the talent shortage? Cognitive computing refers to the “systems that learn at scale, reason with purpose, and interact with humans naturally.”10 They include technologies such as artificial intelligence, text and speech processing, automation and robotics, and machine learning. Their use can typically be categorized in three primary ways: in product applications to improve customer benefits, in process applications to improve an organization’s workflow and operations, and for insights that can help inform decisions.11

For example, an executive at a leading investment firm noted its cybersecurity analysts were spending 30 to 45 minutes working through checklists in the course of investigating security alerts. Moreover, because the work was monotonous, the analysts began skipping steps, resulting in less rigorous examinations of incidents. But by automating the process, investigations were conducted in 40 seconds, and analysts were freed up to focus on remediation. The end result? Productivity of analysts tripled, with each one doing the work it would have taken three people to do prior to the integration of automated processes.12 Not only did this help address the firm’s talent shortage, but it seemed to aid in retention as well—employees were more satisfied now that the tedium of checklist completion was replaced with more challenging and exciting work.

But to truly leverage the power of cognitive technologies, an organization could have employed data analytics to examine extremely large amounts of network traffic. One estimate shows that “a medium-size network with 20,000 devices (laptops, smartphones, and servers) will transmit more than 5 gigabits of data every second and 50 terabytes of data in a 24-hour period.”13 Using supercomputers and artificial intelligence systems to analyze such large data streams could have helped detect advanced threats in near-real-time, identified the most likely types of attacks against the network, revealed patterns of network and user behavior for stronger authentication procedures, and improved management of all devices connected to the network. Thus, analysts would not only accomplish more in less time, their workload would be focused and prioritized on the most pressing issues.

Importantly, such technological advances also require savvy cyber professionals with a particular set of skills that can recognize and act on the insights gleaned from processing big data sets. Just as the cyberthreat is emblematic of a changing world, the talent required to mitigate those threats should also change and adapt to the evolving security environment. Cognitive technologies can help direct the efforts of these professionals, thereby getting the best utilization of their time and skills.

Ultimately, cognitive technologies can mitigate the effects of cyber talent shortages in two primary ways. First, the lingering, unaddressed, or low-priority cybersecurity issues resulting from personnel strains and shortages can be remedied by applying cognitive technologies. And second, they can help inform smarter decisions through the use of artificial intelligence and advanced techniques, such as data analytics, which permits a forward-looking, predictive approach to security challenges.

Moving from the mundane

Discussions concerning the greater use of automation and similar tools for repetitive, mundane, and administrative tasks are sometimes met with the fear that “robots are taking our jobs.” As such, there is often worry and consternation surrounding efforts to integrate more cognitive technologies into different industries. When grocery stores brought in self-checkout kiosks, cashiers feared they’d no longer be needed. The advent and widespread adoption of ATMs caused many to believe that bank tellers were on the brink of becoming passé. But in both instances, the number of grocery store cashiers14 and bank tellers15 actually grew over time, and neither seem in any danger of becoming obsolete.

In the cybersecurity profession, the automation of these sorts of tasks is typically welcomed. With talent already in short supply, time spent on tasks requiring little human problem-solving ability wastes the skills and limited resources available to an organization. A recent study found that organizations spend about 21,000 hours investigating false or erroneous security alerts at an average cost of $1.3 million annually.16 These alerts could be handled by cognitive systems, which would only notify cybersecurity personnel when more investigation is warranted. Similarly, compliance reporting, security checklists, and standard network administration tasks could also be managed through automation, resulting in additional time and cost savings. And given its size, budget, and scope of responsibilities, the federal government’s savings on its nearly $20 billion cybersecurity budget could be quite significant.17

By conducting a detailed analysis of the time its cyber talent spends on particular tasks, organizations can identify the time and money spent on such activities to determine the size of the benefit from automation. Moreover, they may have a much better understanding of where their skills shortage is most acute. As a result, the time and talent recovered from integrating cognitive technology can be smartly reallocated to where they are needed most.

Extending the cyber workforce

Perhaps a greater benefit of cognitive technologies than the automation of repetitive tasks is the analysis of large data sets to identify insights and discern patterns that may have otherwise gone unnoticed. The amount of activity and alerts that occur in and around networks is simply too vast and complex for detailed human examination, even if no workforce shortage existed. But with the assistance of advanced analytics and machine learning, cyber professionals can more quickly pinpoint the cause of issues or even address incidents before they occur. This pairing of data-derived insights with skilled personnel is an especially potent combination that can significantly reduce the impacts of a talent shortage.

Consider predictive cyber analytics. This technique uses supercomputer processing power to sift through extremely large sets of data to identify malicious code, anomalous patterns, and other network threats that may not be readily apparent. When these insights are combined with an organization’s knowledge of its own network, cyber professionals can identify the network’s weak points, characterize the type of attacks the network is most susceptible to, and prioritize addressing the pertinent vulnerabilities. In this way, human-machine teaming can produce better outcomes in less time.

One of cognitive technologies’ greatest advantages for cybersecurity is that they allow organizations to take a proactive approach instead of the more prevalent reactive stance. Being able to predict where threats are most likely to occur, and then prevent them before they do, can change the security paradigm. Cognitive technologies can also contribute to behavioral analytics that can defend against insider threats, identify compromised credentials of employees, or quickly detect breaches. And machine learning allows networks to learn in real time so that when malicious or anomalous events occur, mitigation can begin immediately based on a set of programmable rules or human direction.

Interactive data analysis, proactive discovery, and threat characterization can empower cyber professionals and extend their capabilities far beyond the scope of what could be accomplished alone by even the most talented workforce. With these tools, cyber talent can be more precise in the application of their skills and resolve most issues in much less time.

Cognitive consonance

In a tight information technology and cybersecurity skills market, professionals are usually more than willing to race with the machine instead of raging against it. They are not worried about whether they will lose their jobs to automation, but rather how their jobs will change with its adoption.

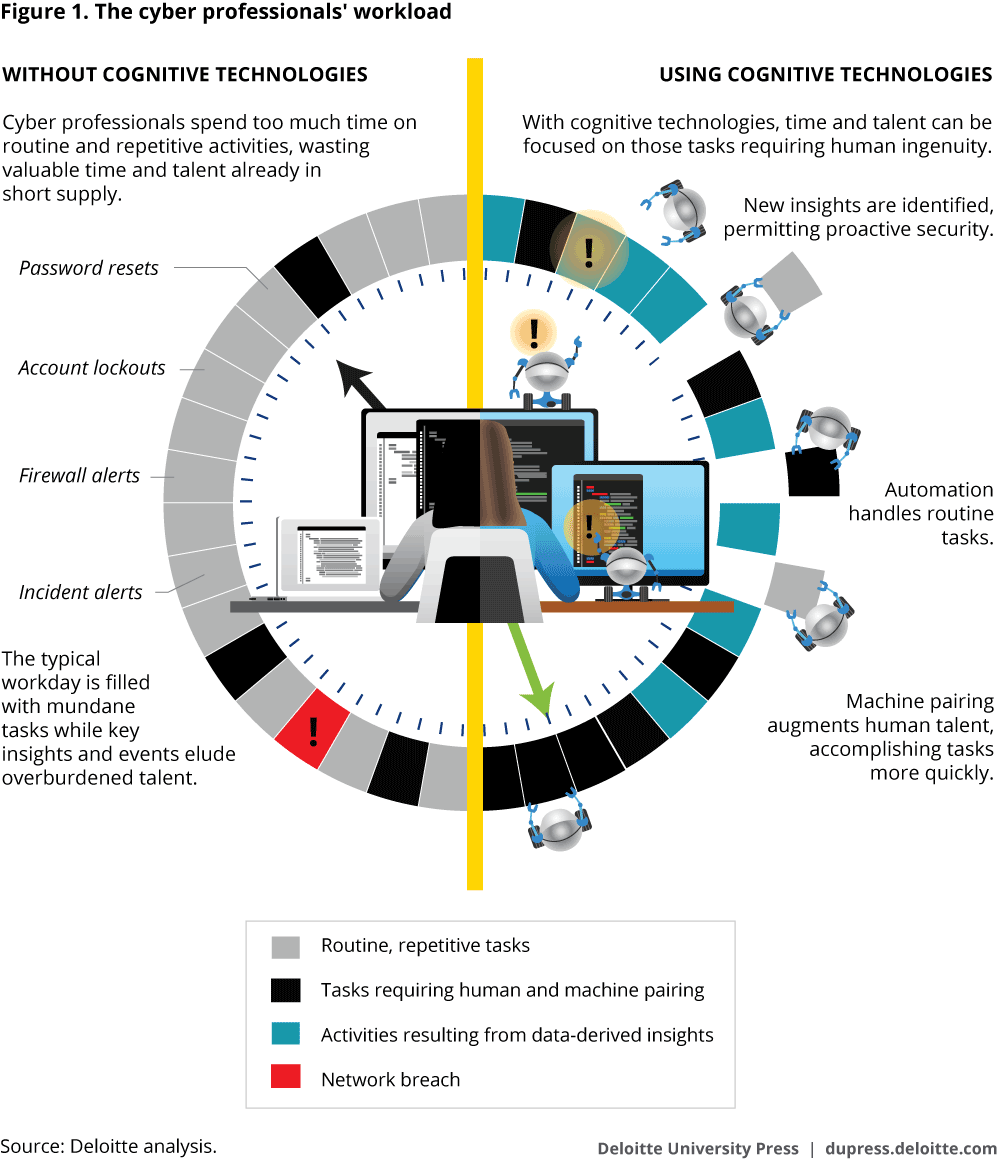

Cognitive technologies can manage rote security tasks, including tasks such as resetting passwords and deactivating malicious hyperlinks in phishing emails, only pushing specific incidents to analysts for further review. They can detect when a network is being attacked and respond at machine-speed to reduce impact. Data analytics and machine learning algorithms can identify threats to a network before attacks occur and recommend measures to address those vulnerabilities. They can scan the reams of legal and regulatory requirements and identify insights that help reduce the number of hours personnel spend on manual compliance and administrative work. And they can automate routine security updates and functions to ensure a network’s hygiene doesn’t lapse due to human error. A cybersecurity professional’s time and talents are put to best use when paired with cognitive technologies (see figure 1).

Put simply, cognitive technologies used for cybersecurity are not a job taker, but a job reallocator. These capabilities allow companies to address workforce shortfalls by reassigning existing personnel without needing to hire or let staff go, while also improving processes and adding rigor to decision making.

Evolving approaches to cybersecurity

The effect of integrating cognitive technologies to address talent shortages often goes beyond insights from advanced analytics and automating specific tasks and actions. It changes the organization, too. Operations change. Workflow changes. Office structure and relationships change. And the processes associated with hiring, training, and retaining talent change. These evolutions are required to meet the demands of cybersecurity operations, compensate for talent shortages, and incorporate cutting-edge technology.

Ultimately, a strategic approach should be taken to integrate cognitive technologies and reallocate cyber talent. Organizations will need to gauge their internal demand for cybersecurity services informed by the threats they face, create a supporting talent strategy for the skill sets they need most, and ensure they are organized in the best way to accomplish their security objectives.

Threat environment

Before an organization hires additional cybersecurity staff or reshuffles its current employees, it should first look at its threat environment and related vulnerability data. Federal agencies have often been targeted because of the vast amounts of personally identifiable information they hold, such as social security numbers, fingerprint scans, and security clearance investigation materials.18

Telecommunications companies have faced denial-of-service threats, particularly with the proliferation of Internet of Things devices. Retail corporations and banks have been victims of cybercrime in which credit card numbers or related financial transaction data have been stolen. Hospitals have been increasingly singled out for ransomware attacks where hackers hold medical information hostage until a payoff is made. And phishing attacks have been the most prevalent form of delivering advanced, persistent threats and are responsible for 95 percent of all successful attacks on enterprise networks in all sectors.19

Knowing which data are most targeted by hackers and which methods they use to compromise networks can help prioritize cybersecurity efforts and the skills necessary to accomplish them.

Talent strategies

Organizations should use the same analytic rigor devoted to key business and risk-based decisions and apply it toward hiring, training, and retention strategies. To accomplish this, they need to better understand the data they have and how best to make use of it to glean insights on workforce strengths and areas for improvement. This approach can help predict workforce needs, which skill sets are available within the organization, and which areas can be augmented by cognitive technologies. Naturally, these requirements change over time, so companies and federal agencies should have an ongoing dialogue about their talent pools. Leaders should routinely ask: Do we have the right workforce skills? Are we automating the right things? Are we letting humans do the right work?

To fill cybersecurity openings, experienced personnel can be hired, or new graduates could be trained and groomed over a period of time. However, advanced analytics and automation reduce the workload of current personnel so that organizations can identify who could be retrained to fill some of the existing job vacancies. And the cost of retraining them is typically going to be a better value addition than trying to hire experienced people in an incredibly competitive market. Further, practitioners note that although industry demand for cyber talent is growing at 11 percent per year, American universities are only meeting 5 percent of that annual growth.20 The advantages of in-house hires through talent reallocation seem immediately obvious.

But where is the talent reallocated? Simply shifting personnel without deliberate matching of skills, aptitude, and preferences can have detrimental effects on an organization, its mission, and the retention of its workforce. As indicated above, cybersecurity professional tracks are rapidly evolving and many require specialization. Organizations have had the most success with their cybersecurity personnel by developing individually tailored career progression plans.21

Returning to bank tellers and the advent of ATMs, banks found that the teller job evolved once people began using machines for simple transactions. So while cash-handling became a less important skill for tellers to have, interpersonal skills became more critical since customers who came into banks had more complex transactions and questions that required more human interaction.22 Some tellers were not as well-equipped for this new role, but banks recognized that displaced cash handlers were detail-oriented, good with numbers, quick learners, and able to focus over long periods of time—the same skill sets that some cybersecurity jobs require, such as regulatory and compliance positions.23 As a result, some banks began training transition tellers for cybersecurity jobs. This is a win-win outcome for workers and banks alike.

Talent reallocation not only provides an opportunity to tailor-match personnel to open positions, it also aids in retention; as workers engage in work better suited to their talents, there is less turnover, reducing the amount of effort required to find and attract outside talent. Further, cognitive systems can enable the reallocation of specific parts of each individual’s workload so that daily tasks can be geared toward solving more complex issues.

Internal processes and structures

New technologies, talent placements, and the ever-present cybersecurity threat will require many organizations to reconsider the roles of their most senior cyber professionals. For many firms, there seems to be a disconnect between chief information officers, chief technology officers, and the human resources department. Further, these senior positions are relatively new additions to the executive level and must contest for resources and prioritization without the advantage of an organizational history that helps validate their requests.

One part of this many-sided challenge regarding cybersecurity leadership is often determining who is responsible for managing operations. Who do the cyber professionals report up to? Is it a chief information officer, a chief risk officer, or a chief operating officer? Where does responsibility for the work belong?

Some of the difficulties associated with hiring and retaining skilled cybersecurity staff can stem from internal issues within an industry or individual organizations, specifically as it relates to structure and accountability. To get this right, organizations should focus on placing skilled personnel in the right positions with the right amount of authority and influence within the organization. If they do not have the right people in this area, then they likely cannot recruit them, retain them, or train them.

Because cybersecurity is a highly specialized and technical pursuit, it can seem out of place in some traditional boardrooms. However, if cybersecurity challenges, opportunities, and objectives are not integrated into an organization’s business decisions, there could be insufficient structural support and accountability to allow for secure and efficient operations. One way to evolve this norm is to incorporate the ideas and input of cybersecurity professionals, from junior personnel up through executives. Once they are fully incorporated and empowered, an organization could be optimally positioned to meet its cybersecurity objectives.

Meeting the challenge

The cybersecurity threats facing public- and private-sector organizations require that they be secure, vigilant, and resilient. This objective is complicated by the widespread shortage of cybersecurity professionals. As other industries have shown, however, cognitive technologies can assist in addressing cybersecurity personnel shortfalls and provide organizations the latitude to reallocate talent to more complex and rewarding positions. But this will require significant forethought and deliberate actions to ensure security and talent objectives are met.

While there is a talent shortage within the cybersecurity profession, there is no shortage of talent in the US or global workforce from which public and private organizations can draw. Organizations that can best integrate cognitive technologies to address labor shortfalls may find an abundance of hidden talent and approaches ready to take on new challenges.