Perspectives

The rising divide

The growing wealth divide in New Zealand post COVID-19

Budget 2021 had been flagged as a recovery Budget, but it also had a strong focus on addressing the rising inequality seen in New Zealand. With the economy in a more advantageous position, the Government has delivered a Budget that utilises the relatively better financial position it is in, while continuing to spend in areas where they see the greatest need.

Budget 2021 included an increase in weekly benefit rates of between $32 and $55 per adult and is estimated to have a positive impact on at least 109,000 families with children, with an average increase in income of $175 per week. Those without children are expected to be on average $88 per week better off.

Inequality in New Zealand has been much debated, especially in the wake of COVID-19 where the impact of border closures and lockdowns have impacted various segments of the population vastly differently. Over the past year there has been a strong narrative around the increasing global and local inequality, exacerbated by a speedy rebound in stockmarkets and housing prices for the ‘haves’ and rising unemployment and wage cuts for the ‘have nots’.

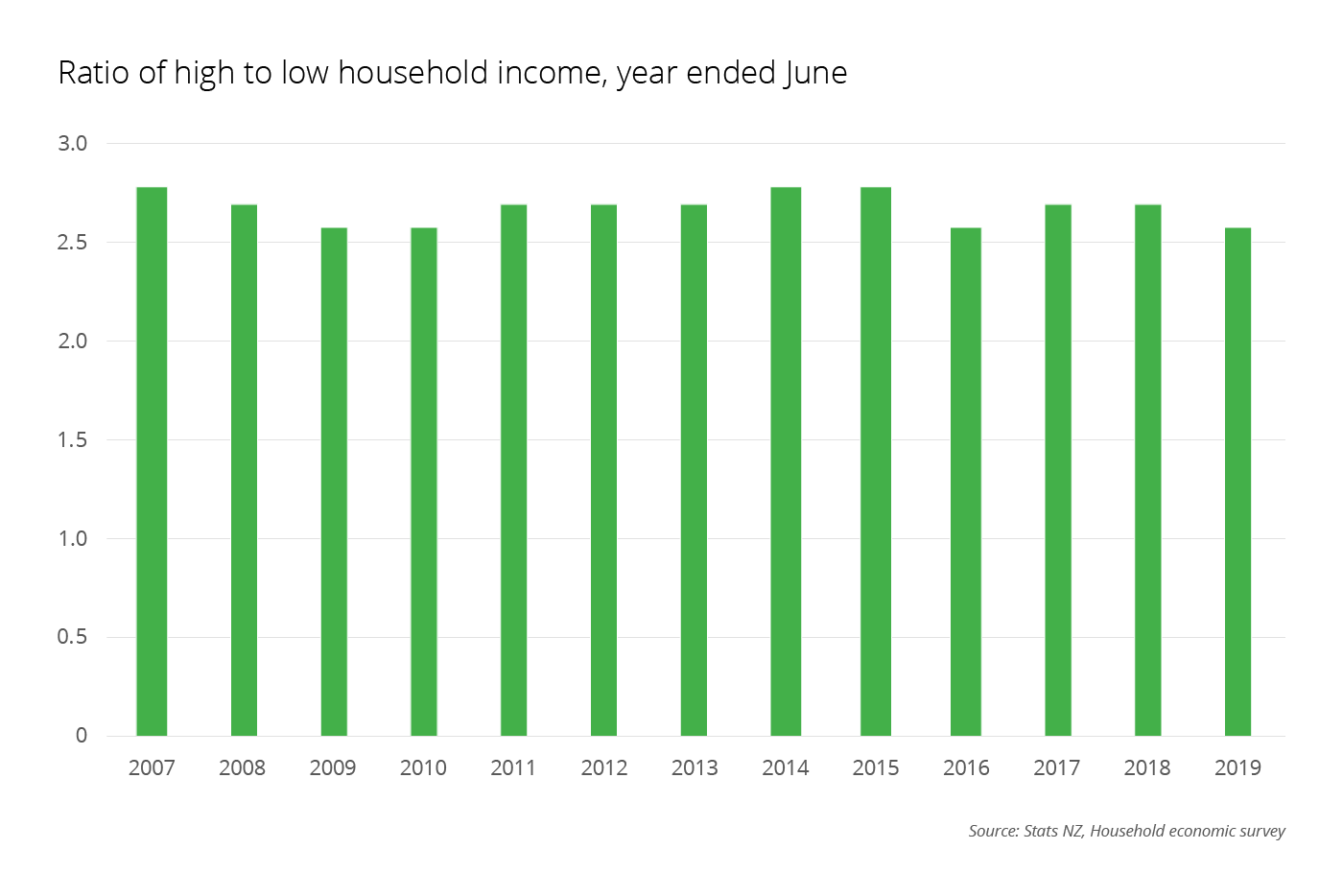

By some measures, inequality in New Zealand has not actually been on the rise. The ratio of high to low household income (80/20 ratio) has been bouncing around the 2.6-2.8 times range for the past ten years leading into the pandemic (see chart below).

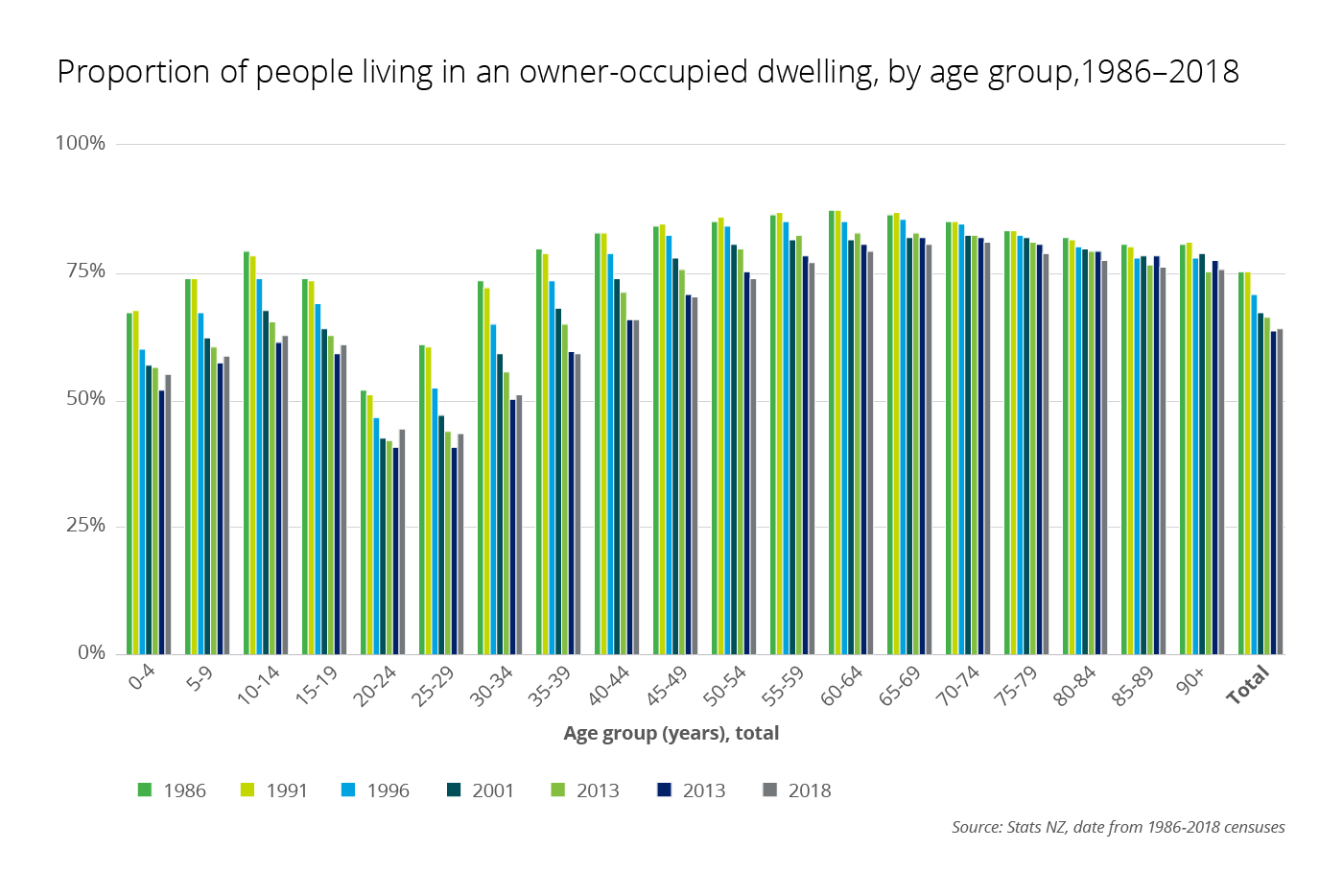

However, many measures of household income don’t account for the dramatic increase in the cost of housing. A large driver of rising inequality has been the difference in wealth outcomes for those who own their own home versus those who don’t. While lower interest rates have benefitted those who have managed to scrape together a deposit, they have contributed to rising house prices and have reduced the return on people’s deposit savings – both of which have made it harder for many people to buy their first house. The bouyant housing market has seen the wealth of home owners climb dramatically over the past ten years, while home ownership rates have declined to the lowest level since the 1950s at 65%.

The New Zealand housing market defied predictions of a post-pandemic collapse and house prices have continued to increase at pace over the last year. This is making it more and more difficult for younger generations and first home buyers to get their foot on the property ladder.

In our view there are several key reasons why house prices have continued to escalate:

- The removal of loan-to-value ratios (LVR) restrictions allowed investors to take advantage of leveraging up against existing property price gains on existing assets and record low interest rates have encouraged an increase in investment purchases as money is cheap to borrow.

- A fundamental shortage of housing stock compared with demand to buy in the market.

- Retirees looking at alternatives to parking funds in term deposits with the value of their money going backwards in real terms. For retirees, many of them know and understand the property market and it is seen as lower risk than investing in shares, with a steady rental return.

- Employment in New Zealand managed to hold up remarkably well overall despite the pandemic, meaning people continued to feel confident buying property and banks remained willing to lend.

House prices have risen 25% over the past year across the country, with double-digit price growth across every region. The median house price in New Zealand is now over 8.4 times the median household income, and for Auckland that ratio is 11.2 times the median. In Auckland, the median house price hit $1.12 million in March 2021 according to REINZ data. As the dust settles on the recent reinstatement of LVR restrictions (generally meaning people need a 40% deposit requirement on investment property and a 20% deposit requirement for first home buyers), we may see some slowdown in price appreciation but we aren’t forecasting an outright price decline at this stage. These changes have come into effect at a similar time to the announcement of rule changes on interest expense deductibility and the bright line test which will take the marginal investor out of the market. The Treasury also isn’t expecting house prices to decline but is forecasting a sharp slowdown in house price appreciation. House price inflation is expected to drop from 17% year-on-year (yoy) in the June 2021 quarter down to annual house price inflation of 2.5% yoy by mid-2025, with price inflation about 4% lower than forecast in HYEFU 2020 in response to the changes in government policy.

Fallout from COVID-19 felt disproportionate

The Budget Policy Statement included a focus on the wellbeing objective of “Lifting Māori and Pacific incomes, skills and opportunities, and combating the impacts of COVID-19”. In the wake of the pandemic, unemployment rose across the country but impacted different ethnicities differently.

Māori unemployment stood at 9% at the end of 2020, compared with 4.9% for the general population. The underutilisation for Māori (a measure of those who would like to work more but can’t find additional hours) stood at 19.3% compared to the national average of 10.8%. Underutilisation and the unemployment rate for Māori women were both higher than that of Māori men. Women of all ethnicities were hit harder by the impact of Covid-related redundancies than their male counterparts, although the female unemployment rate has fallen back to the same level as males at the start of 2021.

The Treasury analysed incomes of all employees in March 2020 and how they had changed for the same people by August 2020. This work showed that Māori and Pacific workers were more likely to have dropped into a low-income bracket (of between $200 and $300 per week). The numbers of Māori and Pacific in this low-income bracket had increased by 85% and 69% respectively, while the number of Europeans in the low-income bracket increased by 27%. Most of the people in this income bracket were on benefits, although some remained employed but working reduced hours.

The wellbeing objective to lift Māori and Pacific incomes, skills and opportunities is strongly supported through several specific funding announcements in Budget 2021. The first is allocating $380 million to invest in a range of housing solutions for Māori which is expected to yield about 2,700 additional homes. Home ownership for Māori is around 35% versus about 65% across the total population.

Additionally, the Government has set aside $243 million to fund Māori healthcare, with $18 million of the funding allocated to setting up Māori/Iwi partnership boards. Given Māori health outcomes and life expectancy are lower than for non-Māori in New Zealand this will be a welcome focus in lifting wellbeing for a critical group. Finance Minister Robertson noted that this is not the final amount to be invested in Māori health in coming years, but is an initial step to establish the frameworks and suggested that additional funding will be coming.

Māori education is being boosted with $150 million with $77 million in property funding to build new and expand existing Māori schools.

The Government is also establishing a Pacific Wellbeing Strategy, but this has a much smaller allocation of $7 million of expenditure and is not specifically targeting health but more general wellbeing outcomes. There is another $67 million of operating expenditure and $1 million of capital expenditure going toward economic development for Pacific communities and supporting training and education.