Private equity industry growth forecast | Deloitte Insights How PE firms can use expertise, technology, and agility to exceed stakeholder expectations

19 minute read

25 March 2021

Often behind the scenes, private equity firms stepped up to support their portfolio companies during COVID-19 in myriad ways. Learn how PE firms will likely continue to play a pivotal role in the economic recovery.

Key takeaways

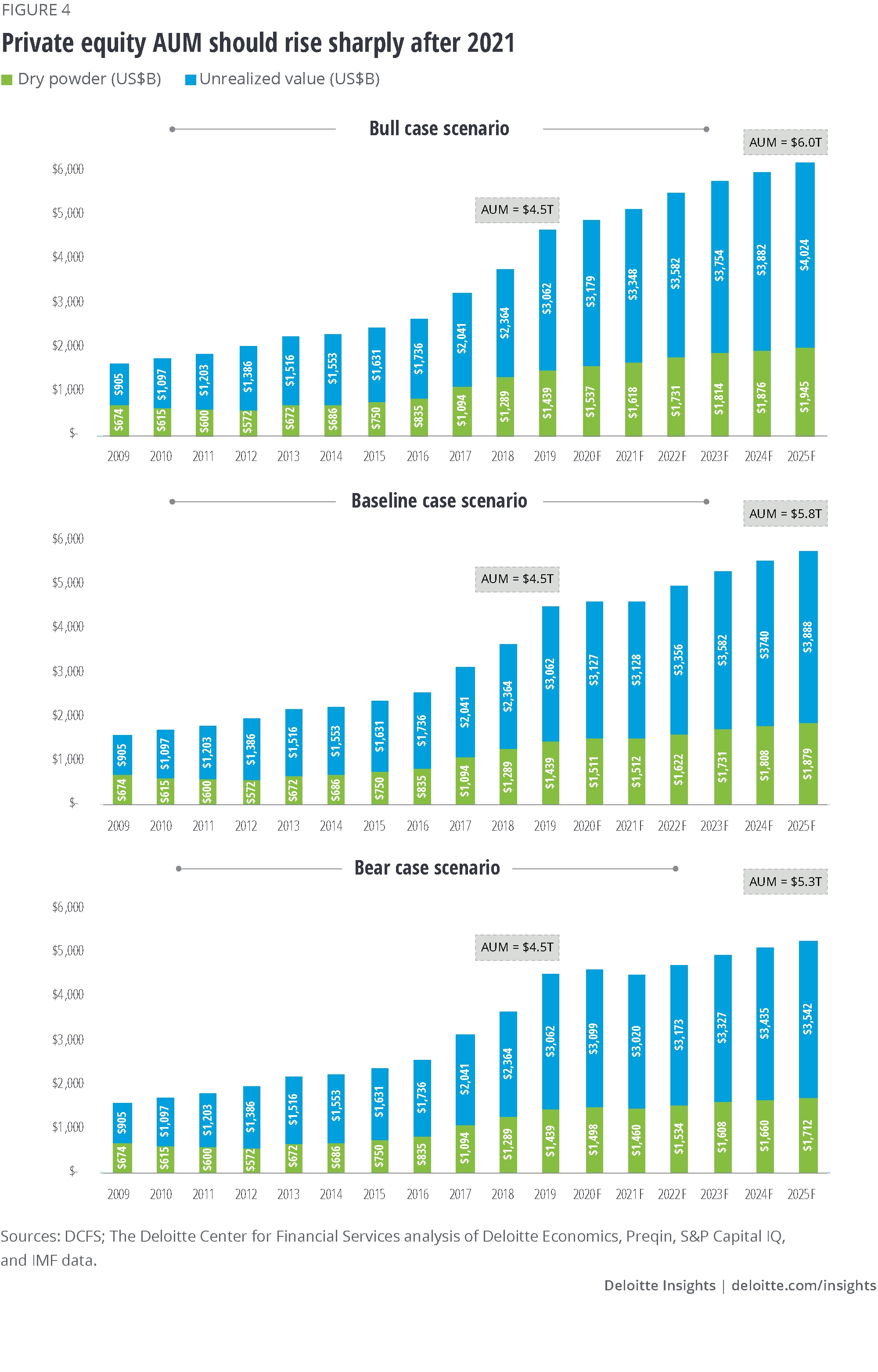

- Formidable growth is anticipated in private equity (PE) over the next few years. Our base case scenario (55% likelihood) forecasts global PE assets under management (AUM) to reach US$5.8 trillion by 2025.

- Since the pandemic hit in early 2020, many PE firms have stepped up to support their portfolio companies in myriad ways. Portfolio companies—especially smaller ones—seem to appreciate PE’s management input and industry connections as much as the capital they provide.

- As portfolio companies look to form partnerships with their PE providers, building relationships and demonstrating industry expertise have become more important than ever. One way for PE firms to excel in this regard is to focus on building diverse teams and boards.

- PE firms that excel at building and deepening relationships with three key stakeholder groups—their own workforces, portfolio companies, and limited partners—will likely be best positioned to cultivate and maintain growth in the long term.

The symbiosis between private equity firms, portfolio companies, and limited partners

Private equity (PE) firms play an important role in the economy: They can help small enterprises grow, and, in turn, generate returns for investors. In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, they often become even more important, providing companies with capital and industry expertise to help them weather the crisis better.

Learn more

Read more forecasts in The path ahead series

Explore the Financial services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Also, as the public market equity valuations rise, PE funds may become relatively more attractive to investors on a valuation basis. The S&P 500’s forward price-to-earnings ratio (27.5 times analysts’ next year’s earnings estimates) has reached a decade-high level.1 In this scenario, more investors may look at asset classes such as PE for opportunities. PE firms’ ability to add value to their portfolio companies and deliver high returns could attract fresh capital and reinvestments, which may fuel assets under management (AUM) growth. The increased interest could boost PE AUM to US$5.8 trillion by year end 2025, up from US$4.5 trillion at year end 2019, based on a forecast developed by the Deloitte Center for Financial Services (for more details, see the sidebar, “Methodology”).

Despite an optimistic forecast, it does not guarantee success for all PE firms. Firms that exceed the expectations of three key stakeholders—their employees, portfolio companies, and limited partners (LPs)—will likely benefit the most. This paper forecasts PE AUM growth and explores how PE firms can deliver on each key stakeholder’s expectations, supported by insights from a survey of portfolio companies.

COVID-19 presents opportunities and challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic offers PE firms an opportunity as well as a challenge to deploy the record US$1.4 trillion in dry powder.2 While the first quarter of 2020 saw little change in the number of deals closing compared with the previous year, in the second quarter, the market tried to assess the effects of COVID-19 on potential investments. As many deals for business- and consumer-facing companies were put on hold, the four-quarter rolling median EV/EBITDA multiple for US buyout deals jumped from 12.9 in Q1 2020 to 15.2 in Q2 2020.3

As PE firms deploy their dry powder in the second half of 2020, they appear to be taking a very close look at the future prospects of target businesses and portfolio companies. COVID-19 pandemic has created a unique situation—corporate problems right now go beyond liquidity stress. They include impact on business dynamics such as supply chains and consumer behavior.4 This environment has led to deal activity remaining strong for businesses with low or positive impact. Meanwhile, some potential sales of companies with less certain futures have been put on hold.5 Considering the uncertainties around a second COVID-19 wave and consumer spending, some PE firms are adopting a wait-and-see approach for new investments, but with this approach comes the risk of missing an opportunity to deploy dry powder.6 To support existing portfolio companies, PE firms are actively working with them to manage through the pandemic and facilitate success.

Apart from fresh investments, firms can add value to existing portfolio companies by providing additional financing and expertise. PE firms’ financial backing and expertise is helping some portfolio

companies navigate through the pandemic and the resulting economic disruptions. Nearly one-half (47%) of respondents in our survey of portfolio companies either received or expected fresh investments from their PE investor during the pandemic. Another 15% received assistance with debt refinancing.

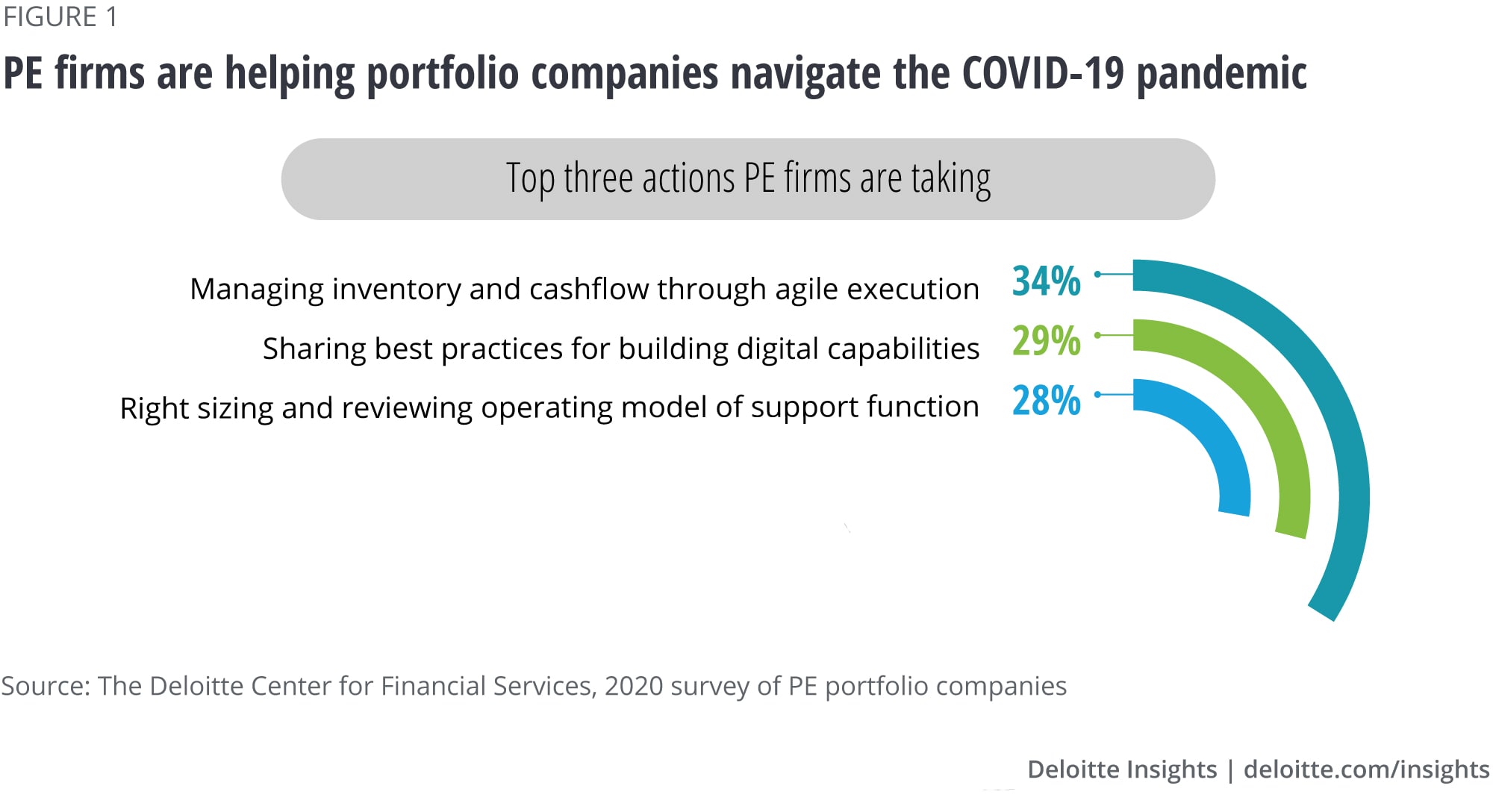

PE firms also helped portfolio companies manage their supply chains, build digital capabilities, maintain business continuity, and secure financing. According to the survey, the most common actions included helping companies manage inventory and cash flow by reviewing bottlenecks, monitoring cash balances daily, and revisiting payment terms (34%); sharing best practices to help companies build digital capabilities (29%); and rightsizing and reviewing the support functions’ operating model (28%).7 Some firms set up centralized crisis-management hubs and appointed leaders to enable information-sharing across portfolio companies and to provide support.8 Firms that helped portfolio companies build robust recovery plans can have better clarity into investment timelines and can potentially generate returns sooner.

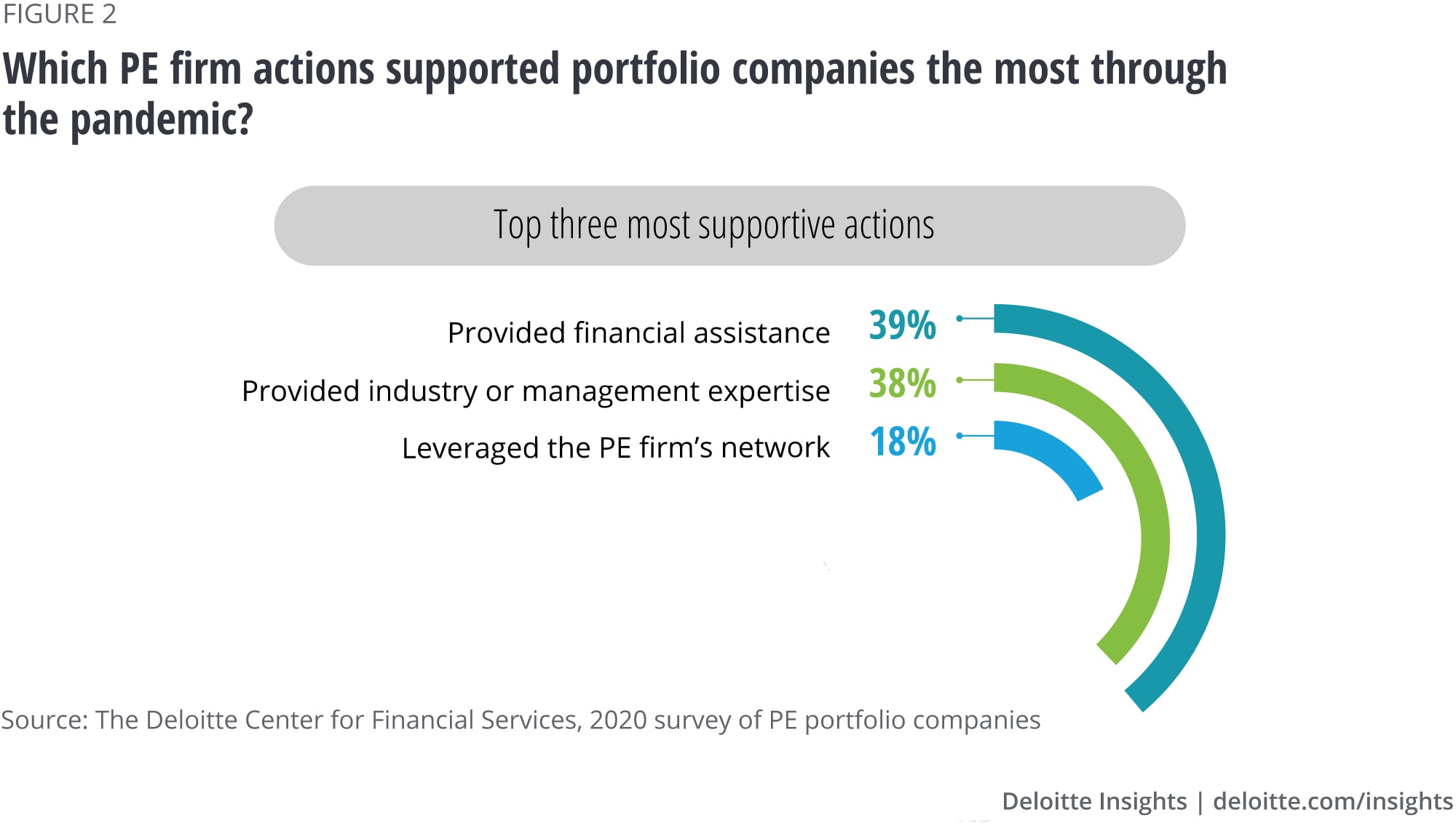

But do portfolio company leaders appreciate the actions PE firms are taking to support their companies through the pandemic? To varying degrees. Portfolio company respondents were asked to describe what they liked the most about their PE firm’s support. Financial assistance, comprising provision of capital and implementation of cash management plans, emerged as the most valued action. Delivering industry or management expertise was a close second. This involved refining companies’ operating models, planning for diverse scenarios, and providing advice through internal and external resources. Access to the PE firm's network, which included knowledge- and resource-sharing, centralized procurement, and network introductions, ranked third.

PE network assistance examples

- Apollo Global Management Inc. increased the frequency of conference calls with management teams and created an online information-sharing portal that served as a common communications channel.

- HireVue Inc., a Carlyle portfolio company providing video interviewing systems, offered three months of free access to other portfolio companies to help them hire during the pandemic.9

Some portfolio company respondents—mostly from companies expecting a decline in revenues—expressed concerns about PE investor actions. Their top concern cited was financial controls—such as those placed on investments and expenses as well as a lack of capital infusion. It was followed by tighter talent policies, such as headcount reduction and reduced compensation, while excessive operational scrutiny ranked third. That said, these actions may be necessary to help at-risk portfolio companies survive.

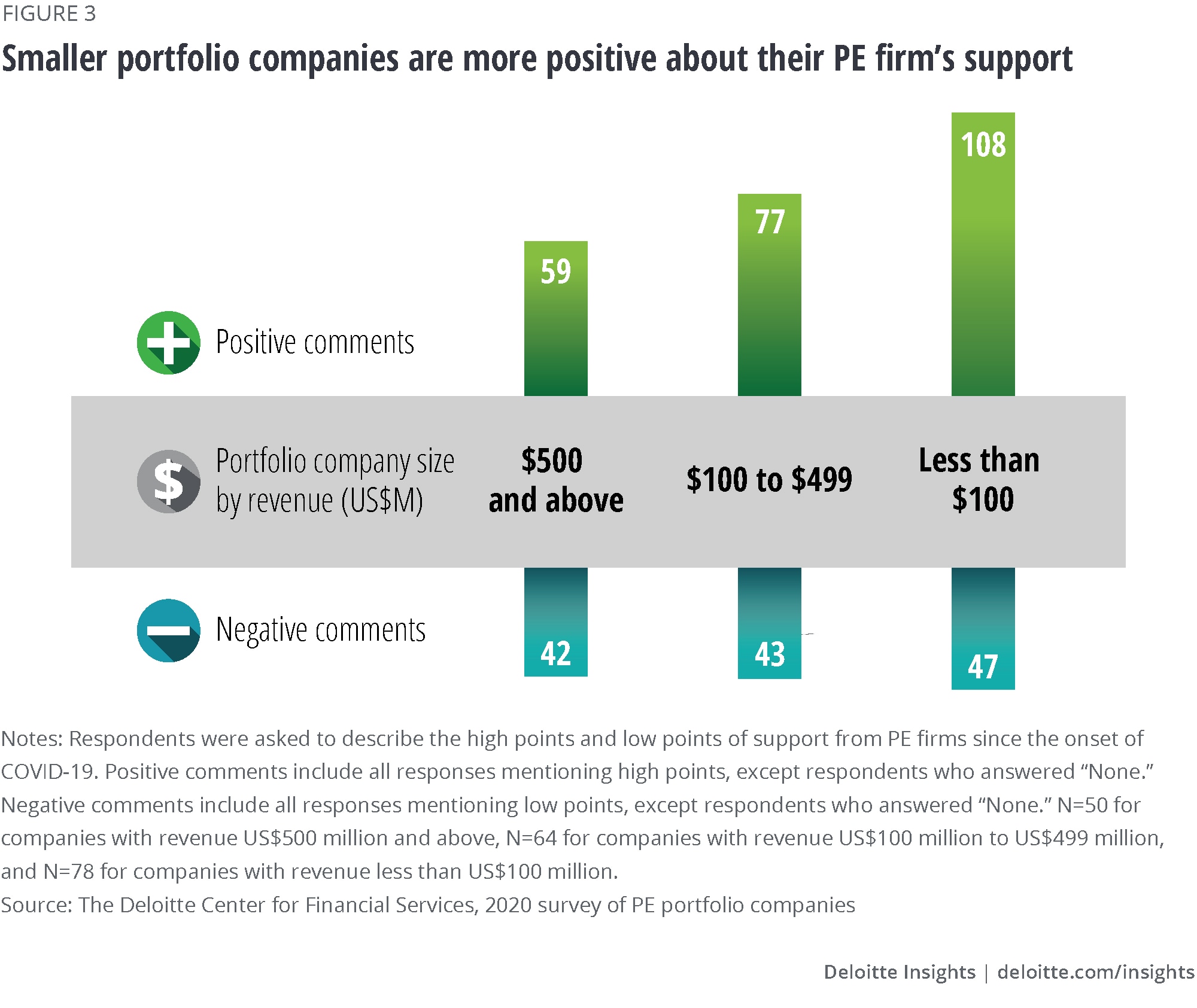

PE backing was viewed overwhelmingly positively by surveyed portfolio companies. Just 3% of portfolio company respondents did not receive any substantial help from their PE investors, whereas nearly two-fifths (39%) stated they experienced no shortcomings in the support they received. Satisfaction levels of surveyed portfolio companies varied with size (figure 3). Companies with less than US$100 million in revenues spoke most favorably, while those with more than US$500 million in revenues seemed the least satisfied. This may be because larger portfolio companies likely received less attention and financial assistance because these firms had greater internal resources.

How PE firms managed the crisis will likely influence their returns for years to come. The pandemic may turn out to be a pivotal point in the history of PE firms, widening the gap between winners and losers.

Uncertain times can boost growth in PE

As economic activity returns to normal growth levels in the post–COVID-19 world, PE will likely play a key role in the recovery. Unlike other investment vehicles such as mutual funds, ETFs, and hedge funds, PE firms can wait for the right moment to deploy cash committed by limited partners. They also have more control over the duration of investments, allowing them to time exits to benefit from better valuations. Additionally, because PE firms are actively involved in the management and oversight of portfolio companies, they can effectively steer these companies through a crisis.10 In times of crisis, PE firms can also buy companies at attractive valuations, improve their operational performance, and realize substantial profits when they exit.

We can get a glimpse of PE funds’ performance with vintage years corresponding to years of crisis by looking at the great recession of 2007–2009. Even though many PE funds did not catch the bottom of the cycle and stayed on the sidelines a bit too long, they delivered double-digit returns.11 For instance, buyout funds with vintage years 2008–2011 had a pooled IRR of 13.0% compared to 9.2% for vintage years 2004–2007.12 From this experience, many PE executives have learned that agility during times of uncertainty can influence fund returns.13 Implementing their past learnings, PE firms can benefit from uncertainties presented by the pandemic, deliver better returns, and grow their AUM.

To estimate PE asset growth, we built a model that forecasts AUM growth under three different scenarios: baseline, bear, and bull (figure 4; see sidebar, “Methodology”). The baseline scenario, which has a 55% likelihood of occurring, assumes that US GDP grows by an average of 2.9% annually from 2020 to 2025.14 It estimates that global PE AUM may reach US$5.8 trillion by the end of 2025. These results indicate a 28% jump in AUM over 2019, despite staying steady for the initial two years of the forecast. In our bear case, which assumes 1.5% average GDP growth, AUM is expected to grow to US$5.3 trillion. But if GDP growth averages 3.4%, our model predicts that assets grow to US$6.0 trillion in 2025, denoting the bull case. Fueled by economic uncertainty, all of these forecasts reveal the opportunities PE funds have to grow AUM; the amount of growth will likely depend on investment returns and investor behavior.

Methodology

The quantitative model forecasts global PE AUM using nominal US GDP and global public equity market capitalization as the explanatory variables. The model envisages three outcomes based on the economic scenarios forecasted by the Deloitte Global Economist Network. To stabilize the impact of public equity markets’ volatility on PE AUM, the model incorporates an elasticity factor that considers the historical relationship between them. It also modifies the relationship between public and private market valuations based on whether public equities market capitalization is growing or declining.

We also conducted a survey of 200 portfolio companies globally to glean insights on the support they received from their PE investors during the COVID-19 crisis. The respondents were diversified across geographies, industries, and revenue sizes.

What is driving PE demand?

The demand for PE funds is increasing as high returns and perceived low volatility continue to drive inflows from both existing and new institutional investors.15 In 2020, 66% of institutional investors invested in PE, up from 57% in 2016.16 Additionally, retail investors can now access PE due to new regulations. Let’s explore the trends in investor allocations and why many investors find PE attractive.

Institutional investors increase allocation

Since bond yields are expected to stay low and public equity returns are likely to be below historical annualized returns over the next 10 years, institutional investors—pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, foundations, investment companies, banks, and family offices—are increasing allocation to private capital.17 US public pension funds’ average investment return assumption is 7.1%, which is higher than the past 5-year average returns of 6.5%.18 In contrast, the median net internal rate of return (IRR) for PE funds with vintage years 2008–2017 has continuously been 12% and above.19

With bond and public equity return expectations unlikely to rise in the near future, many pension funds are increasing their private capital investments to meet these increased return targets. PE is likely to benefit from this trend. Institutional investors’ average target PE allocations rose from 9.9% of total assets in 2019 to 11% in 2020.20 Even COVID-19 failed to dent target allocations for PE. In fact, according to a recent Preqin survey, 41% investors plan to increase their PE allocations over the next 12 months.21

More investors gain access

Recent US regulatory actions have also helped widen the PE investor pool. In August 2020, the SEC broadened the definition of accredited investors to include individuals and entities that are financially knowledgeable.22 In June 2020, the Department of Labor (DOL) provided guidance that PE in retirement plans meets existing ERISA fiduciary requirements, paving the way for defined contribution plans to invest in PE.23 In response, plan sponsors will likely increase exposure to PE assets gradually over the next few years.24 Consequently, 401(k) assets may boost PE AUM in the long term; however, the regulation is expected to have a limited impact of up to US$50 billion per year over the forecast period.25

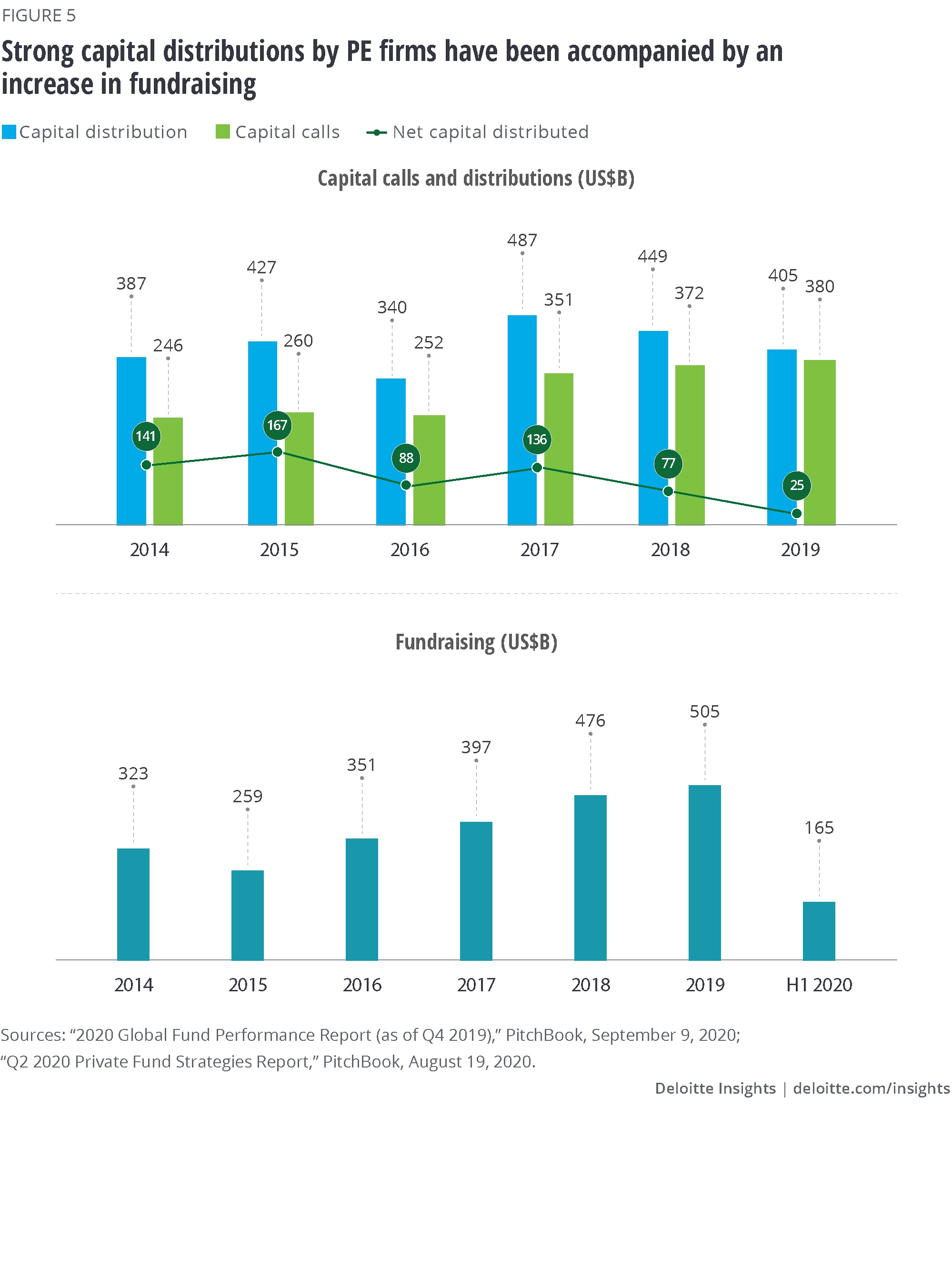

Capital distributions drive reinvestments

PE’s high returns have been accompanied by large capital distributions to LPs. Distributions have increased from under US$300 billion levels prior to 2012 to US$405 billion in 2019.26 Over the past five years, PE funds have returned more than US$2 trillion to investors.27 Also, capital distributions have exceeded capital calls, leaving more money in the hands of the investors. High absolute returns is the primary reason more than one-half (55%) of institutional investors cited for investing in PE.28 Delighted by their past experience, LPs are increasingly willing to reinvest part of the distributed sums in PE funds, which has resulted in AUM growth.

Satisfying key stakeholders can help PE firms grow

Despite the heathy growth forecast, not all PE firms are likely to benefit from this asset growth to the same degree. Success will likely depend on how well firms can meet the expectations of three key stakeholders: the PE workforce, portfolio companies, and LPs. Let’s look at some of the important considerations for each stakeholder.

Creating a diverse PE firm

As competition among PE firms intensifies, top private companies are likely to be looking for more than just financing from their PE investors. With record dry powder at their disposal, PE firms are chasing the same set of quality companies.29 Firms that do the best job delivering industry knowledge and building relationships will likely stand out and be poised to win deals and cultivate unrealized gains. Building, developing, and retaining strong deal teams may influence a firm’s ability to deploy dry powder in this competitive environment.

One way to stand out is to prioritize building diverse teams and boards. Building and cultivating a diverse team allows firms to gain a broad spectrum of perspectives that may resonate with potential portfolio companies’ management teams, especially from underrepresented communities. Hiring fund managers or board members with a wide variety of backgrounds and experiences enables firms to invest in more companies with diverse founders and increase the diversity within portfolio companies in general.30

PE firms that have diverse teams and boards can also be more innovative and may be able to source more and better deals, which could improve performance. Furthermore, one venture capital firm found that their investments in companies with women founders were more resilient and generated higher returns on investment.31 PE firms are aware of these benefits and are making efforts to improve diversity. In June 2020, more than 10 PE firms committed to adding five board seats for diverse candidates at each of their firms.32

Creating value for portfolio companies

PE firms need a strong track record of creating value for portfolio companies to help attract and win great deals. Using their own industry expertise and the areas of expertise of the company’s management, PE firms can tailor value-creation plans for each company. A value-creation plan identifies, quantifies, and outlines the implementation of performance improvement initiatives across the entire value chain.33 Once the plan is finalized, firms can work toward achieving each of the outlined action items. Implementation of such plans, however, has to be carefully executed so that PE firms are not perceived as micromanaging the business. Successful execution of the value-creation plan is a key determinant of investment returns.34

Formulating effective value-creation plans in consortium deals is typically more complicated. Consortium deals involve multiple PE firms with varied expertise that work with a portfolio company’s management to add value. At the outset, the partnering PE firms should decide on factors such as each firm’s roles and responsibilities, the strategy for business growth, governance structure, sharing of fees and expenses, and exit strategies. The expertise of the deal sourcing and management teams in handling these matters will likely play a key role in helping portfolio companies grow.

PE firms can leverage their networks to help portfolio companies boost revenues and reduce costs. While new customer introductions can increase revenues, portfolio companies can help reduce costs by obtaining scale discounts using central procurement of services. Our survey found that nearly one-half (44%) of the portfolio companies participating were able to improve operating margins through these types of ownership synergies.

Firms can also use advanced technologies to further boost operating efficiencies. Technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and robotic process automation (RPA) have enabled nearly two in five (39%) companies to improve their operating margins. Also, PE firms can utilize technologies such as big data and AI to benchmark portfolio companies based on factors such as customer base, brand reviews, product reviews, and employee sentiments to identify best practices.35 PE firms that share best practices among their portfolio companies can help them grow.

Build satisfaction and loyalty among limited partners

Limited partners are the third key stakeholder for PE, and their satisfaction is often essential to growth. LPs want to invest in quality companies and have access to strong deal flows, liquidity options, and well-defined exit strategies. While performance may be the primary driver of LP satisfaction, transparency, fee control, flexibility, and focus on social responsibility also contribute to LP satisfaction.

PE firms serve as the conduit linking LP capital to private companies enabling LPs to meet their target allocation and providing growth capital to these small companies. The importance of this role is increasing since the pool of private companies to invest in is large and growing. The number of US companies with more than 20 employees increased 2.8% from 2007 to 2017.36 Over the same period, the number of US listed companies decreased 2.0%.37 Moreover, secondary buyouts (SBOs) are increasingly becoming the preferred exit route for PE investors and the SBO marketplace now has enough liquidity to support even billion-dollar deals (figure 6).38 From 2006 to 2019, the number of SBO exits increased by 5.2% per year, while PE exits via IPOs declined by 7.3% per year.39 While there have been fewer SBOs and IPOs in 2020 due to the pandemic, some prominent unicorns are planning for IPOs in late 2020.40 The rising popularity of SBOs has resulted in more companies staying private longer.

PE firms that maintain a flexible operating model can continually monitor industry trends to capitalize on new opportunities for fundraising and deal-making. Based on the latest trends, firms may consider revisiting operational aspects such as product launches, deal sourcing, and exit strategies.

The rise in SBOs (figure 6) accompanies a change in investor sentiment. In 2020, many investors are preferring lower-risk strategies that SBOs offer. Now more than one-half the investors (56%) surveyed expect that secondary buyout funds will present one of the best opportunities for returns over 2020–2021, significantly more than the 34% of respondents in the previous year.41 PE firms can capitalize on this trend, for instance, by increasing the use of SBOs for deal sourcing. As deals grow in size, firms may also consider forming buyers’ consortia to manage risks.42 Furthermore, to add value to a company acquired through SBO, PE firms may need to offer expertise in operational areas that were left untouched by the previous PE investor. To do this, firms could need to develop niche expertise such as industry-specific or functional knowledge.43

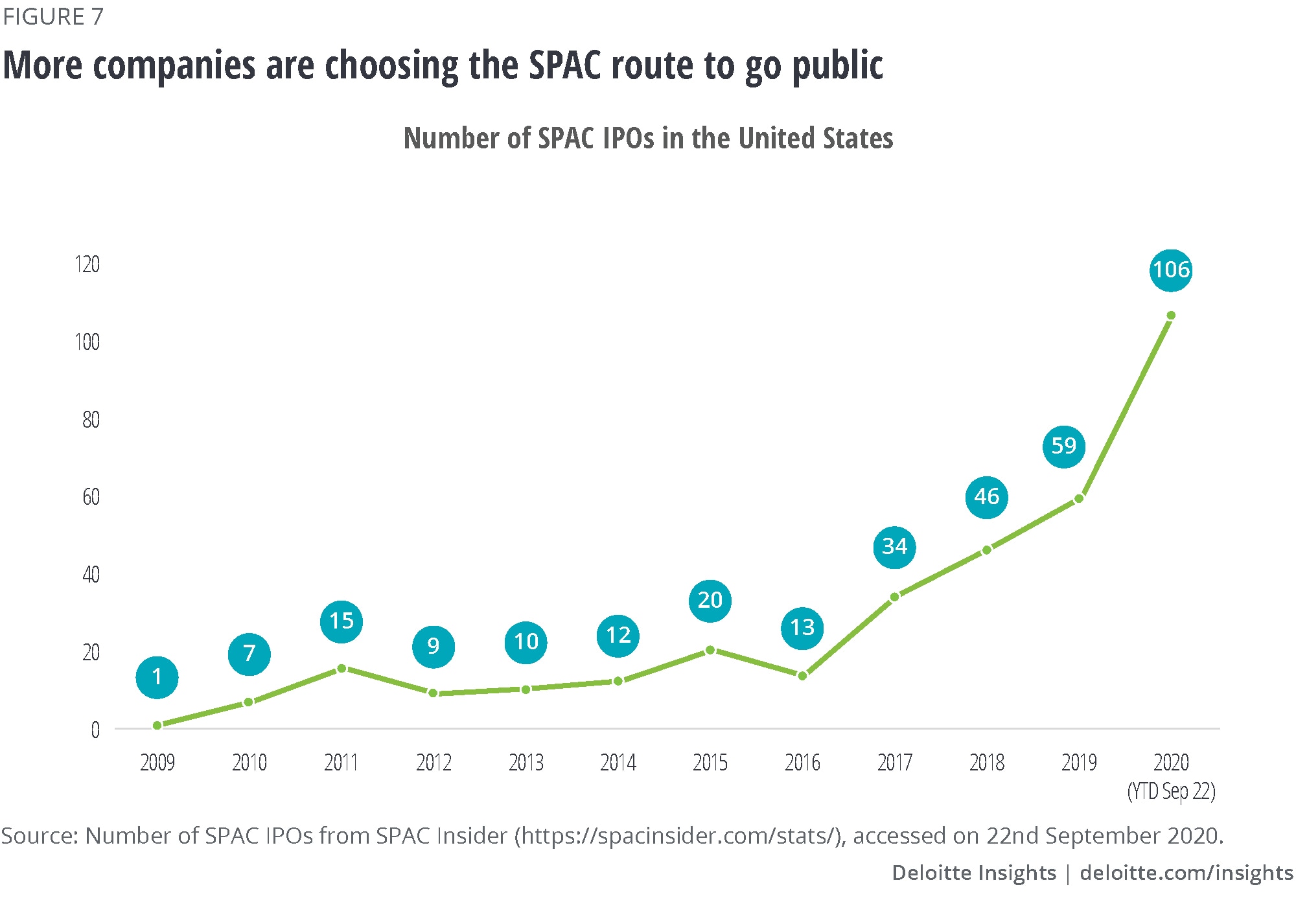

Rising activity in the Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) space is another trend that PE firms can leverage (figure 7). The process of listing through the SPAC route may be simpler and quicker than traditional IPOs.44 SPACs are becoming an increasingly popular route to take companies public and can be used as an exit strategy. TPG Capital is one firm using this strategy, taking the SPAC route for exits as well as acquisitions over the past few years.45 Moreover, SPACs that target PE portfolio companies are also coming to the market. For example, Forum Merger III Corp.—a SPAC that aims to collaborate with PE funds to generate liquidity and maintain some ownership while enabling portfolio companies to list on public equity markets—filed for an IPO in July 2020.46 Keeping up to date with potential exit strategies, such as the latest SPACs trend, can help build satisfaction among LPs.

General partners (GPs) recognize that LPs have been increasingly demanding transparency over the past few years. And, as concerns grow over the impact of the pandemic, nearly four out of five GPs globally (79%) expect investors to demand more performance reporting transparency over the next year.47 To increase transparency, firms can deploy technological solutions that provide on-demand financial reporting to LPs. Firms that are able to provide daily valuation may be able to gather assets from defined contribution retirement plans.

PE firms can use technology and automation to lower their operating costs as well. Cloud-based storage and delivery of data and analytics capabilities enables PE firms to sustainably save costs.48 Firms that operate at a lower cost can sustainably lower fees to reward investors while protecting their operating margins.

Succeeding together

The PE industry is poised for significant growth over the next five years: Our base forecast shows AUM increasing by US$1.3 trillion. While many paths exist to succeed in this growing industry, satisfying key stakeholders—employees, portfolio companies, and limited partners—will likely be the cornerstone of each strategy. Some firms may focus on retaining and attracting top talent by providing equal opportunities in senior management. Top talent in high-achieving PE firms can help portfolio companies achieve sales and profit growth by providing these companies with expertise and network connections. Finally, firms that are responsive to evolving investor preferences, such as customer experience and product choices, can develop stronger relationships with LPs. PE firms that excel in each of these areas will likely earn an outsized share of the expected AUM growth. Together, they can drive industry growth.