Why has the UK missed out on a trade boom? has been saved

Article

Why has the UK missed out on a trade boom?

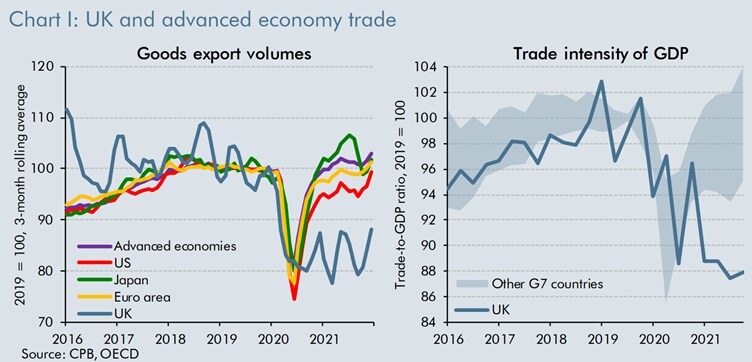

As part of its Spring Statement forecasts and analysis the OBR provided an update on UK trade and specifically the impact of Brexit. The OBR suggested that the UK has missed out on a trade boom which most other similar economies have taken advantage of as the global economic rebound took place. Furthermore, that the UK’s trade intensity (trade as a share of GDP) has declined much more than other countries. Much of the commentary around this simply put it down to Brexit. But the reality is more complicated. We examine what might be driving these two phenomena.

The first thing to say is this is all complicated by volatile data. Different organisations measure trade data differently with, for example, the ONS and Eurostat showing different impacts of Brexit on UK/EU trade. The ONS has also changed its approach to trade data from the start of 2022, so for consistency we will focus on data up to the end of 2021. Data collection has also been impacted by the pandemic.

The second point to make is that some of this can probably be put down to currency movements. On a trade value basis once currency fluctuations are accounted for, the performance of UK exports doesn’t look all that much worse than its peers, because the Pound has been relatively stronger over the past few years. That said, there haven’t been any large rapid shifts in the Pound relative to other currencies in recent years which could fully explain the performance of UK trade relative to other countries.

Nevertheless, with those two caveats in mind, it is still worth trying to explore what is going on with UK trade and why.

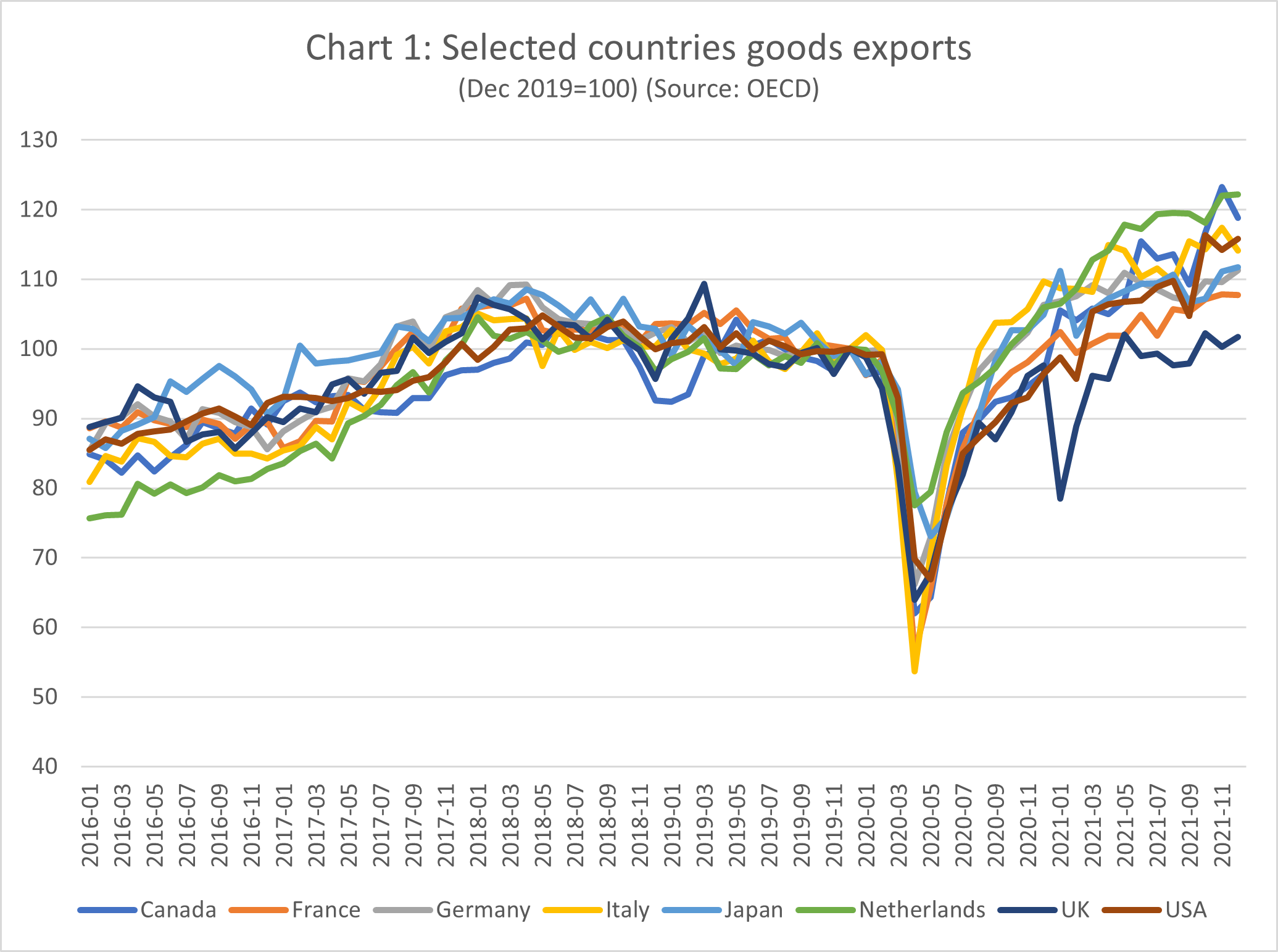

Missing out on a boom in goods exports

As chart 1 above shows, it does look to be the case that the UK has missed out on a trade boom in goods. As demand for goods, and particularly durable goods, boomed during the pandemic most countries have seen their exports rise. The UK’s have, at best, plateaued after recovering from the worst of the pandemic.

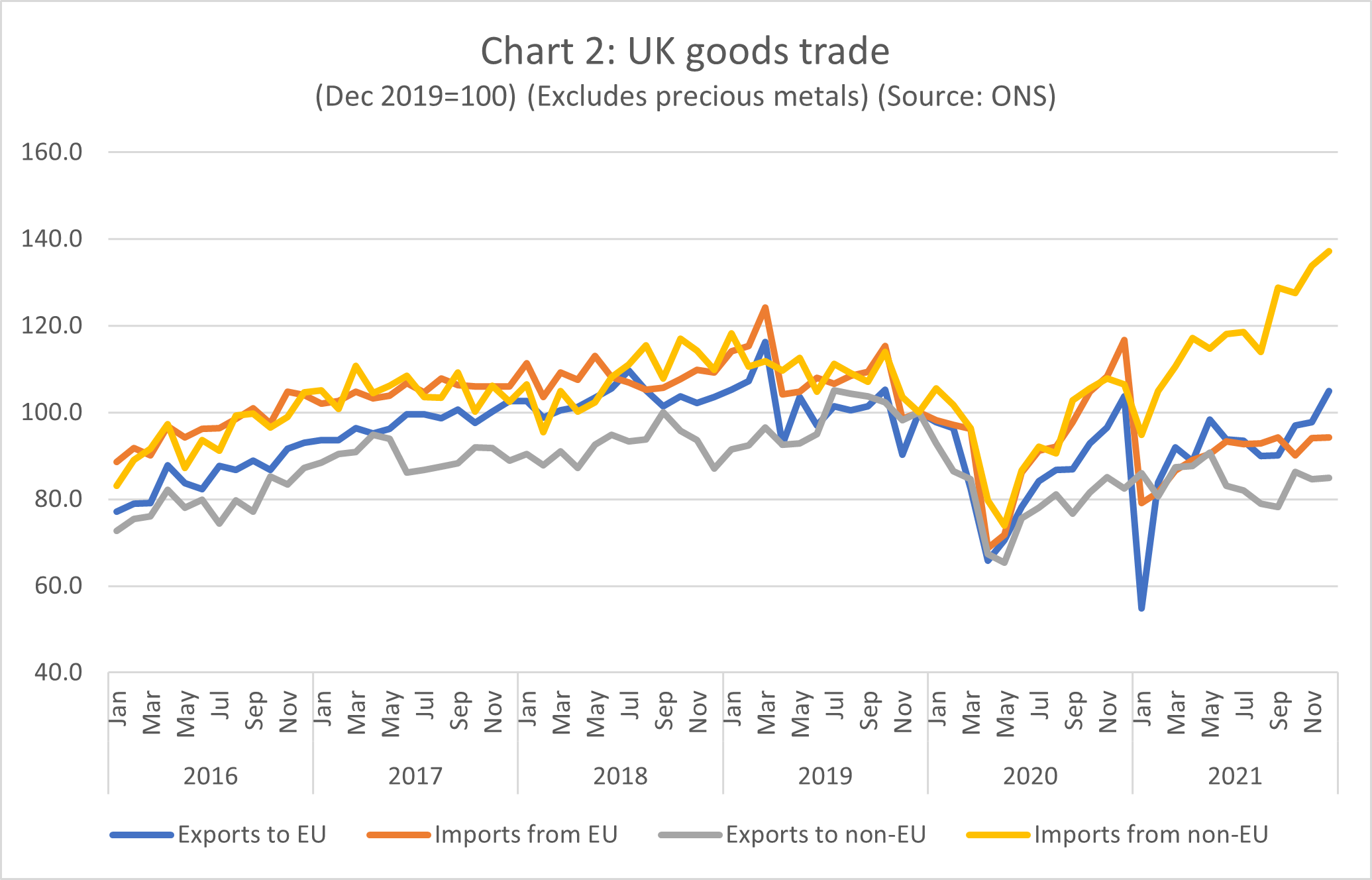

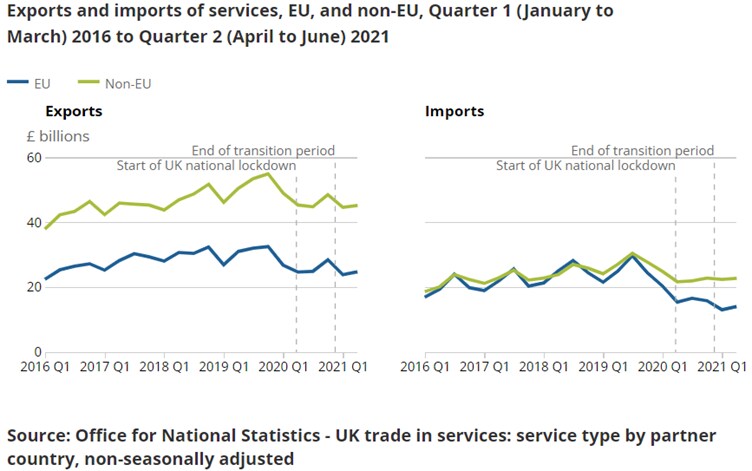

As chart 2 above shows, this is largely down to the fact that UK exports to non-EU countries have performed poorly. Clearly, Brexit had a significant impact on UK exports to the EU initially, but they have largely recovered to their previous levels by the end of last year. But as chart 2 shows Brexit continues to weigh on imports from the EU and while some of this has been replaced by rising imports from non-EU countries it probably accounts for some of the reduction in UK trade intensity. The real question then, is why have UK exports to non-EU countries performed poorly especially relative to other countries?

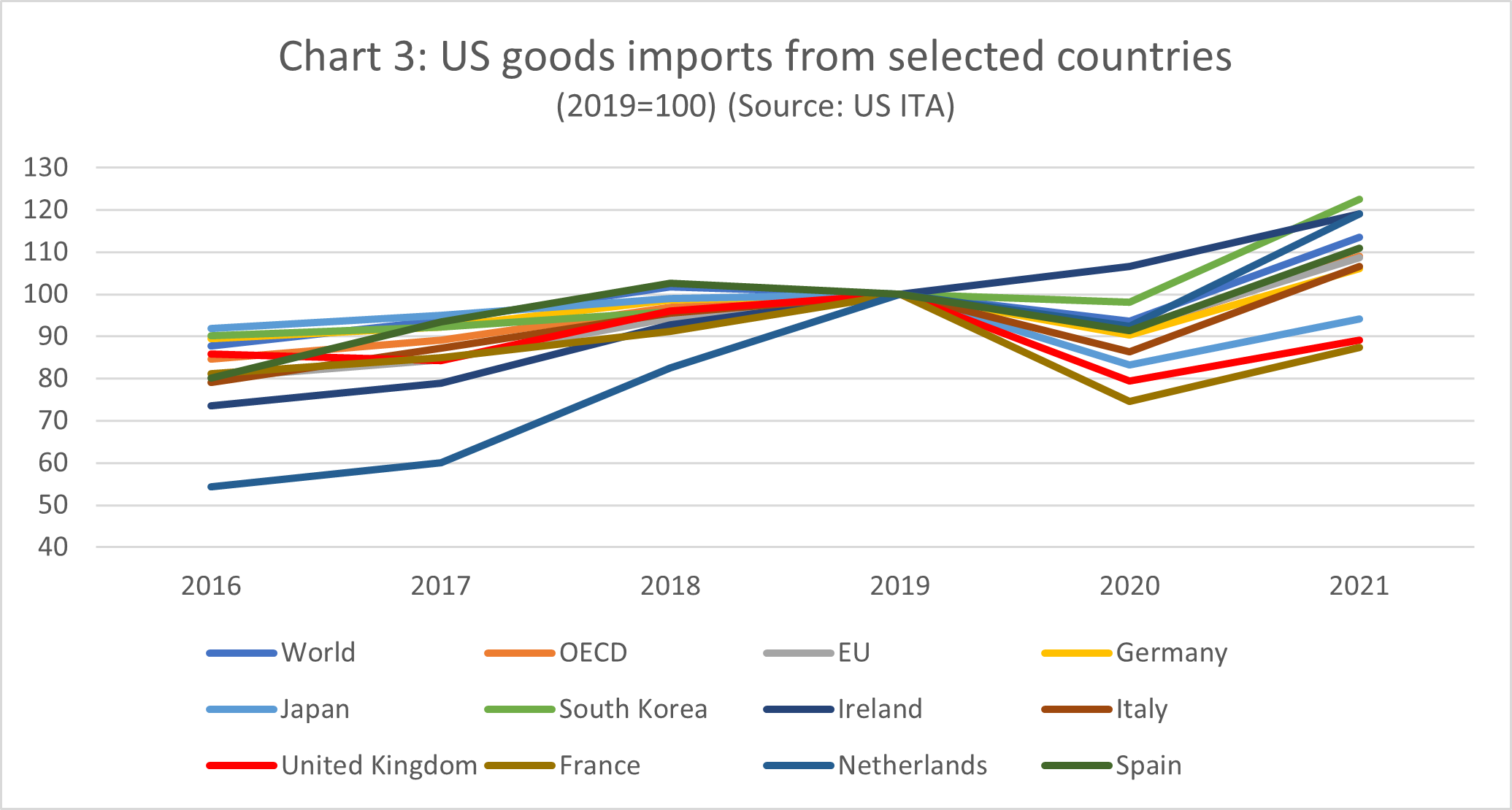

This is much harder to answer, not least due to data constraints. But we can gather some indications. Chart 3 below shows US imports for selected countries. Having undertaken significant fiscal stimulus, US demand has been growing quickly following the worst of the pandemic. As the WTO forecast, “in 2021, demand for traded goods will be driven by North America thanks to large fiscal injections in the United States”. A number of countries have seen this translate into an increase in exports to the US; however, the UK is not one of them. Given the US is a significant driver of global trade and the UK’s second largest trading partner (after the EU) it’s likely this is a large part of the explanation for why the UK has missed out on the trade boom.

Digging even further into the data, we see that the US’s increase in imports stem from a few areas. Specifically: computers and electronics, chemicals, electrical equipment and primary metals. Of these areas the UK is a very minor exporter to the US of computers and electronics ($4bn pa), electrical equipment ($1.7bn pa) and primary metals ($2.2bn pa). This suggests that the UK simply doesn’t export/produce some of the products which have seen a boom in demand.

That said, chemicals is slightly larger at $11bn pa. Ireland, Germany, Switzerland and Japan have seen steady increases in chemicals sales to the US in recent years. While the UK’s picked up as well in 2021, it was still only back to levels seen in 2016. It is possible this is partly due to additional Brexit impacts with the sector as a whole becoming less competitive due to additional costs and supply chain disruption. That said, this is a phenomenon started while the UK was still in the EU so it is hard to put it down entirely to Brexit. As a whole it raises questions around the competitiveness of the UK chemicals sector, though further investigation is needed to establish what is behind this.

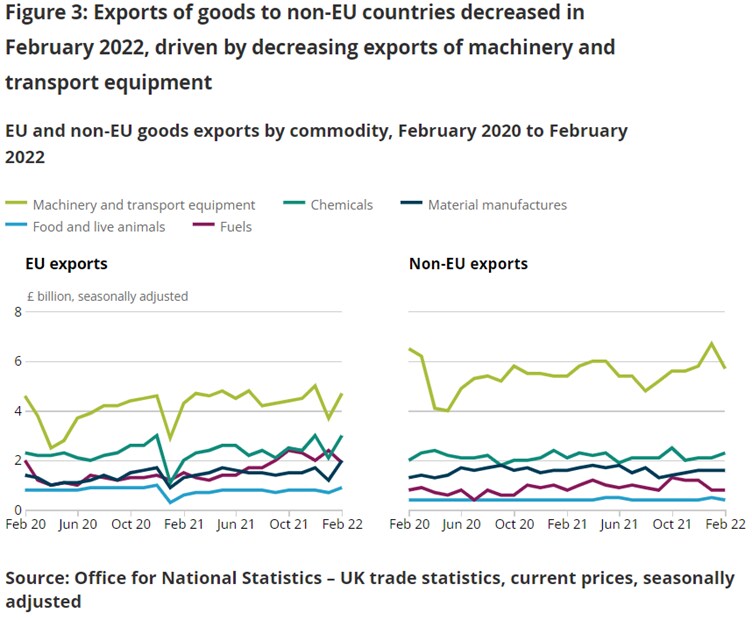

This is reinforced by data and analysis from the ONS. As figure 3 above shows, UK exports of machinery and transport equipment to non-EU countries have largely recovered to pre-pandemic levels now but clearly have not boomed.

What does all this tell us then? To the extent the UK has missed out on a trade boom in terms of its goods exports, part of the reason seems to be weak exports to the US. This is at least partly down to the fact the UK doesn’t really produce or specialise in the types of goods (electrical equipment etc.) which have seen a boom in demand. But even in areas where the UK is traditionally quite strong (e.g. chemicals) the expected increase in exports has failed to materialise.

Unfortunately, it is hard to pinpoint why that is, with further research needed. It is not impossible Brexit plays a role, for example, by reducing the competitiveness of certain sectors overall due to a rising cost base - or that some sectors have seen firms move exporting bases into the EU and therefore the rise in exports has taken place there. But there just isn’t enough data or evidence to conclude either way at this point.

Declining trade intensity

As the OBR chart above shows, the UK looks to have lagged significantly in its recovery in terms of trade intensity (i.e. trade as a share of GDP). We’ve already looked at goods trade, and it could be that declining imports from the EU and struggling exports to non-EU countries could play a role in why UK trade hasn’t held or increased its share of GDP. However, the real question is what role services trade has played here.

Services trade accounted for 36% of UK total trade at the end of 2021. It has been at roughly that level since 2015, though pre-pandemic it peaked at 40%. This is a larger share than most economies - even similar developed economies. As such, the fact that services trade took a large hit during the pandemic and has yet to fully recover (unlike goods trade) would likely have had more of an impact on UK trade intensity than many other countries.

The combination of Brexit and the pandemic is also likely to have been a factor here. The ONS has already produced an analysis of these two events and their impact on services trade. As the ONS charts above show, services exports to the EU took a significant decline at the start of the pandemic and are yet to recover. While there is no obvious additional decline when the UK EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) came into force, it is certainly possible that the additional barriers to trading services across borders have played a role in keeping services exports to the EU subdued. As with goods trade though, the charts show the more obvious impact has come in imports of services from the EU, which declined significantly during the pandemic and then declined further post the introduction of the TCA.

As the charts above show, the decline has been largely down to travel and transport services. Again, this is expected due to the pandemic and the impact it has had on tourism. It is also worth noting that there has been a decline in financial services exports to the EU, likely down to the loss of passporting and some firms moving certain operations inside the EU. The fact imports from the EU in particular remain more subdued than other UK services imports and exports also suggests that the additional barriers to selling services into the UK (e.g. work permit/visa requirements) is having some impact in deterring EU services suppliers. But it is still early days and, of course, the pandemic is not yet over. So only time will tell whether this will be a lasting impact.

In our experience, clients are only now starting to grapple with the challenges around services provision and the complexities of the TCA. It is also worth noting here of course that the pandemic has fundamentally changed the way services are provided, with much more being provided remotely/digitally in the future. This effect, along with the new barriers to UK/EU services trade, are together pushing in the same direction in terms of subduing travel and transport services.

Conclusion

Bringing this all together, we can tentatively conclude (subject to the caveats above) that the UK has missed out on a trade in goods boom post the worst of the pandemic. Brexit has played some element in this, but mainly through the subdued levels of imports. By far the larger factor is the poor performance of UK exports to non-EU countries, especially the US. This is partly because the UK found itself poorly placed to take advantage of the increased demand since it seemed to largely fall in areas where the UK is not a major exporter. However, there are some areas where the lack of an increase in exports will raise concerns about the UK’s competitiveness.

Furthermore, given the government has a stated aim to not only significantly increase exports (having set a target of £1 trillion by 2030) but also to build a high tech, high productivity economy, this data should raise some concerns. It will be interesting to track over the next year or two to see whether various policies the government has put in place have an impact or not. In particular, given the challenges in exports to the US whether the current negotiations with the US will have any meaningful impact on UK/US trade.

The broader fall in trade intensity will be less of a concern, not least given the fact that the UK continues to be a very domestically driven economy. The fall here seems to be largely down to the prolonged downturn in services trade due to the pandemic. The slow pace of recovery though and the interplay with Brexit will still give some pause for thought. The longer-term issue for the UK, as with many other countries, is to consider how services trade is changing post-pandemic and how to remain competitive in the new landscape.

Finally, this all suggests that while Brexit has had an impact on UK trade, these particular problems are not entirely down to Brexit and likely not even mainly down to Brexit. It is easy to reach for it as an excuse for all problems but doing so risks obscuring the other complex trade challenges business are facing and makes it harder to find the right solutions.