Automation is changing how work gets done, and companies need to shift workers’ focus from routine tasks to more value-creating activities, the kind machines can’t replicate, say John Hagel and Maggie Wooll of Deloitte’s Center for the Edge.

“Before we start talking about who’s going to do work and how it’s done and all the rest… What is work? What should it be? ”—John Hagel, founder and co-chairman, Deloitte Center for the Edge

TANYA OTT: The workplace is rapidly changing. We’re communicating and collaborating in new ways. Robots and automation are taking over some of the more routine tasks. Today on the Press Room, we examine the future of work …

Tanya Ott: I’m Tanya Ott. If you’ve listened to this podcast before you’ve probably heard me say some version of, “This is the podcast about the issues and ideas that are important to your business today.”

One of the biggest issues we’re talking about these days is what work is going to look like 10, 15, or 50 years from now. How will technologies like artificial intelligence and automation change the way we work? What kinds of jobs won’t exist anymore? My guests today say, before you worry about who’s going to be doing the work and how it’s going to be done, you need to stop …

Read the article

Explore the Future of Work collection

Listen to more podcasts

Subscribe on iTunes

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights app

… and ask a more fundamental question.

John Hagel: What is work?

Tanya Ott: That’s John Hagel.

John Hagel: I'm the founder and co-chairman of the Deloitte Center for the Edge. The Center for the Edge is a research center that is focused on identifying emerging business opportunities that should be on the CEO's agenda, but are not. And we do the research to persuade them to put it on the agenda.

Tanya Ott: My other guest is Maggie Wooll.

Maggie Wooll: I lead research on the Future of Work and learning and human potential for the Center for the Edge.

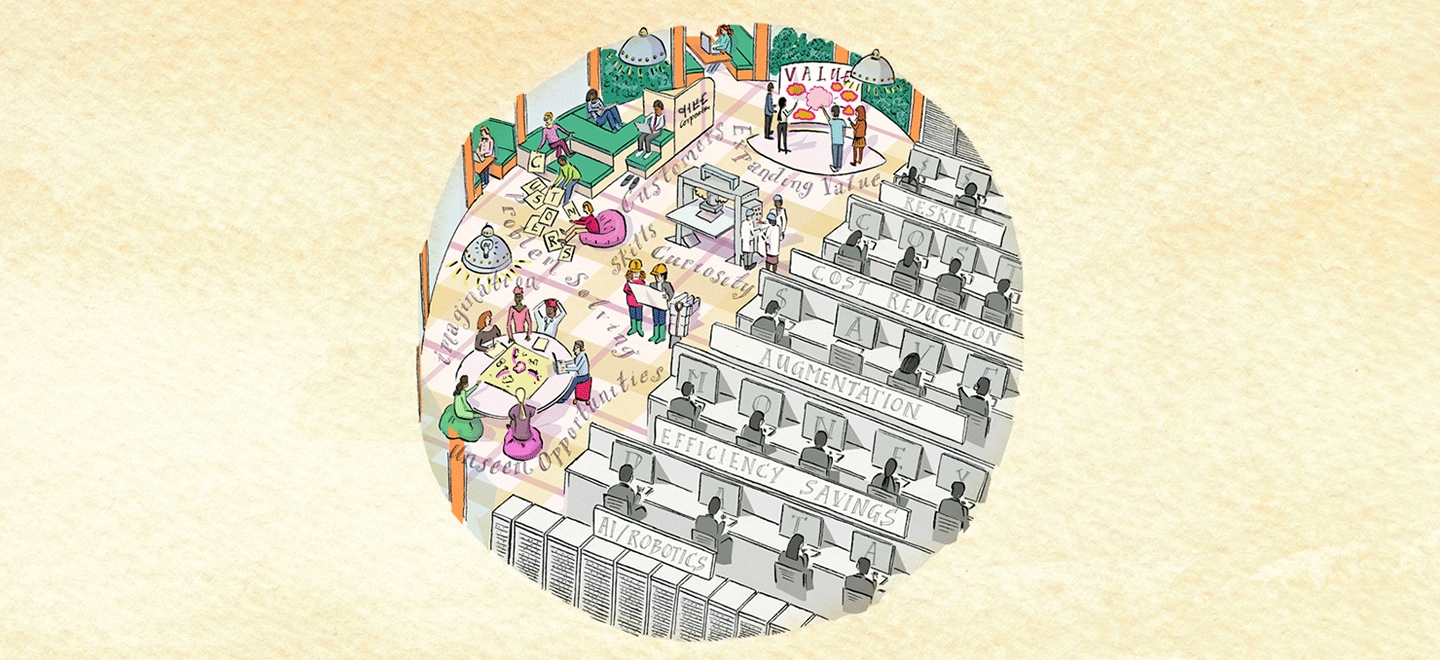

John Hagel: Our belief is that there is an opportunity and a need for a fundamental shift in how we define work for people, and it has to [happen] at a very high level with the notion of moving from work that typically is tightly specified, highly standardized routine tasks to work that is about addressing unseen problems and opportunities to create more value. [Those are] very different conceptions of what work should be, and at the risk of overgeneralizing, we would say most work in most institutions today around the world is in that former category of tightly specified standardized tasks.

Tanya Ott: When I think about work I think I go to work at 8 o'clock in the morning [and] I come home at 5:00 at night. I pretty much know what my day is going to look like. I mean, that's a job, right. That's work. But you're saying, Maggie, that's not exactly maybe what work should be.

Maggie Wooll: Work that is laid out in predefined [tasks], and what we talk about as being routine—that is the stuff that is not being automated just now. It's been being automated for years in various forms, whether that's robotics or computer programs behind the scenes, but things that are pre-defined and very standardized can be done by machines. The last couple of years have really started to put a finer point on it—for humans, what is the work we do? And it's really starting to do the stuff that we want to do, that we're good at doing—understanding other people, thinking creatively, and solving problems. That's the stuff that we used to have to fill in around the gaps when we were spending our days doing really routine tasks. It is definitely a mindset shift, as well as an actual shift of how time is spent and what the expectations are.

Tanya Ott: It's a lot of shifting. You write at the top of your article, "In the age of artificial intelligence, the answer to a more optimistic future may lie in redefining work itself." But embedded in that statement, John, is this idea that even though we've been assured that automation is going to automate some processes and free up workers to focus more on rewarding tasks, there's still this huge concern amongst a lot of people that I talk to about what the future's going to look like. I hear people saying they're worried about losing their jobs to robots. And the question is why wouldn't they be, given that a lot of companies have responded to competitive pressures by rolling out cost-cutting measures that often include eliminating positions and asking people to do more with less.

John Hagel: That's the key challenge, and frankly our belief is fears are justified. If work is tightly specified standardized tasks and if the focus of the institution is on cost-cutting, then yes, all that work is going to get taken away and we're going to lose our jobs. But again, our view is [that] the missed opportunity is, what if we took that capacity that's now been freed up, that should have actually never been done by people to begin with, that's work that machines can do much better than we can, and refocus those people on creating more and more value for the institution. Now we're suddenly turning it into a situation that it benefits the institution. We're shifting the focus from just cost reduction to more and more of value creation. How can we have more and more impact in the marketplace and within the organization to create more value for the marketplace? Now, all of a sudden, it's how can we get even more workers doing that? We don't have enough. There's more and more value to be created. So, our sense is that it is a challenging shift, we don't want to underestimate it at all, but on the other hand it's something that already is happening. In our research we do case studies to support the research, and Maggie can talk to some of the examples that we've come up with in terms of companies and institutions that are already starting to redefine work and the way we're talking about.

Tanya Ott: I'm sure a lot of companies will say, “We're already doing this, we're all about the customer experience. We're all about tapping into the potential of our employees.” We see that kind of language scattered across their advertising and their promotional materials. But what you're saying is you're not even anywhere near there yet—work as a broader picture.

Maggie Wooll: It is interesting because there is a sense from some companies that, hey, this is what we already do. We already give power to the workers. We already work in teams. We're already thinking about that customer. That's true. There has been a shift in that direction in some companies, but if you actually look at where people spend the majority of their time, if you talk to the frontline workers, and if you look at how they're actually being measured and rewarded, you'll see that a lot of it still has to do with task execution that is really done within pretty tight boundaries and with the goal of getting more throughputs and being very predictable. What we're talking about is actually shifting to something that is, as John said, creating value in an unpredictable world when you don't know what the right outcome is going to be, and have that actually be the day-to-day full-time work of people, not something they do on the side or a guideline for them as they go through their everyday tasks, but that they actually are focused on as their full-time work.

John Hagel: And I should say a key assumption behind this perspective is that the world, the markets, the global economy is changing in a fundamental way. We used to be in a much more stable environment where you could tightly specify and standardize tasks, and that was the way to be very efficient. In a world that's more rapidly changing, where on a daily basis we're confronting new situations that have never been anticipated, that kind of work model becomes very inefficient because now workers are scrambling to figure out, “This wasn't in the process manual. How do I deal with this?” Our belief is it's an opportunity because of the way the world is changing. It's not only an opportunity, it's an imperative. If we continue to just hang onto the process manual, we're going to become more and more inefficient.

Tanya Ott: I want to dig into a case study so we could put a real clear picture on this. One of the companies that you look at is California-based Morning Star, which is an agribusiness company that does tomato processing and things like that. They took an interesting approach to empowering their employees. Maggie, what did they do?

Maggie Wooll: Yes. The Morning Star company is very interesting. It's easy when we think about redefining work to kind of think about certain types of workers who could do this more creative, imaginative work and who could be trusted managing their own work. But the Morning Star company is a low-margin business with a lot of low-wage workers, and it's been around for a few decades. So, they are a little ahead of time. They operate on a principle of self-management. That means no one has unilateral authority over another person. Basically, they let each employee at every level shape their own responsibilities and relationships with their colleagues. What this ends up looking like is that there's kind of an assumption of trustworthiness, competence, and the ability to observe and make judgments and act in the interests, not just of the company, but of one's co-workers. They take this responsibility to the company and to their co-workers very seriously. I'll give you just one example that brings it to life.

One thing they do is that they're a pretty aggressive harvester, which means that a lot of vines come in with the tomatoes. So, tomatoes get unloaded at the plant; they're kind of floated down this flume of water, and that flume was getting really clogged up with vines and required a lot of sorting. There was a factory mechanic who'd been there since high school, and he had an idea that a bar that rested across the flume could snag these vines and eliminate the need to sort. He was a pretty good welder, so he just welded up a prototype and tested it out on just one flume. He watched it and it seemed effective. It didn't damage the tomatoes. It didn't slow down the flume. Then he pulled in an automation mechanic who helped him to design a small motorized system to automatically dump the vines. And when that proved out, then he shared it with a few other co-workers. They implemented it on another couple of flumes and only at this point did they actually raise it to higher visibility and suggest that it get implemented in other places.

This is just one example. The idea [is] that you see something, you observe for a little while, you try something, you pull another colleague to informally try it out again, and keep very responsibly trying to come up with a better solution to it. You never have to make presentations and go seeking approval from management just to try something out. So that was pretty amazing to me.

Tanya Ott: You can only imagine what it must feel like for them. If they try something out, it works, they iterate on it, and then it becomes something really successful in the company. To be able to look at that and say “I made that. That was my idea.”

Maggie Wooll: Yeah. One thing the Morning Star company does—and this was a company that started out with this vision and it started out smaller, so they were able to control it—they hire for people that they think can work in this type of environment. But what they have found is that even in their harvesting teams out in the field—a real farm labor—the teams there take it seriously, as well, and they'll see one harvesting team is more productive than another and so they go out and look and say, “What are they doing that's different?” And it's because everyone feels the latitude to tweak what they're doing, see what the result is, and then keep looking for better answers. People tend to stay there for a long time because it is not only effective for the company, but it's a good way to work for the people as well.

Tanya Ott: What I like about that example is that oftentimes when we're talking about these kinds of redefining the way work is done, it seems to focus on white-collar, knowledge workers. And this is not that. This is something different.

Maggie Wooll: That was one thing we found that was both affirming and really exciting when we went looking for examples: You can find different examples in all types of fields. It's interesting to start thinking about what creativity looks like in different contexts or what imagination looks like in different contexts. When people push back and say this is only for a certain type of person, they're viewing what imagination is or what creativity is in a very narrow way, [as if] we're all going to paint pictures and make songs. It's not that at all. Within context, these things look different.

Tanya Ott: You've got another case study that's interesting and that is Quest Diagnostics—one of the largest providers of diagnostic testing and laboratory services. They were facing some competitive pressures. What was going on with Quest?

Maggie Wooll: What we looked at specifically was what was going on in their call centers. Call-center work can be very difficult and, in their case, they were having tremendous turnover in their call centers and really poor customer satisfaction with what was happening with physicians calling in, medical centers calling in, as well as actual patients calling in. The call-center agents really felt like they were unable to answer the questions, to resolve questions, and there were very long wait times. What they did is they started small and grouped a couple of their call-center teams into actual pods. And this was like 12 to 15 agents with a supervisor, and they physically moved them together so that they could hear each other. These pods are actually competitively selected, so each of the teams came up with videos to say why they wanted to be part of this new way of working. Turns out there was a huge amount of interest in doing a better job. Nobody likes to do a bad job, and they were frustrated that they weren't serving customers well.

One thing they did is they gave the call agents videos about who these ultimate patients were to get them a lot closer to why the work they were doing mattered to customers and what some of the issues are. They also refocused the supervisors from being about managing absences, which is what they spent most of their time doing, to coaching employees. The supervisor was actually listening in. They could stop and discuss collectively what was working and what wasn't. Then they gave those pods of agents the time, resources, and latitude to actually identify problems and implement solutions. They would have a board where they'd come up with their idea cards and put them up, and then, once a week, they'd go through that and pick which ones they collectively were going to try to solve. Some of them were very simple. One thing was when an agent received a call, they'd get a little whisper in their ear that told them if the speaker was a Spanish speaker. Before they never knew what the person had selected when you do the dial-in. Things like that just started to save time.

Another thing they did was to come up with an actual physical board that had all of the products that they were talking about that would sit there right in the pod so that they could look over and reference. [That way] the agent actually had a good sense of what the person on the phone was asking. All of this not only led to better customer service but a huge improvement in employee morale. It lowered attrition as well, which anyone who works in a call center knows is a big part of maintaining performance.

Tanya Ott: There are so many things about the way that companies operate today that can make it challenging to redefine work in these ways. Take, for example, the way that we evaluate people. It's often tied to making numeric goals, whether it's sales goals or parts made or whatever it may be. But those evaluations don't take into account the kind of time and energy and creativity that we see expressed in the Morning Star or the Quest Diagnostics examples. That's a pretty big cultural shift to try to implement in a company. What are your thoughts on how companies can start tackling some of this?

John Hagel: It is a fundamental cultural shift. It affects virtually everything, ultimately, that an institution does to create environments for their workers. Our recommendation is not to try to go in and do this for everyone tomorrow morning. It's a massive change. Instead, target a particular area in the company that has both the potential and the need for this kind of redefinition of work. Part of the process we advise in terms of selecting your initial target area is identify a work group or a set of workers where the performance is really meaningful to the overall company. If you could improve the performance of that work group, it would make a big difference for the company as a whole. It's what we call “metrics that matter.”

Part of it is looking at work areas where they are already starting to automate some of the work so [that] it's freeing up capacity. Because if you just, on top of all the routine tasks, tell workers to be creative and do problem-solving, you're probably not going to get a lot of effective response there. You need to find ways to free them up from the work that currently is occupying their time and attention. Then focus on performance. We still believe metrics matter. You need to focus on what are the metrics that would assess whether workers are, in fact, starting to create more and more value for the company. But it's typically what we would call frontline metrics. It's not going to be overall revenue or profitability, but it's something meaningful that that work group could be addressing where you could start to see accelerating performance improvement. Once you've got that, start to work with the workers to change the behaviors. In these scalable efficiency cultures that we currently live in, the key message to all the workers is failure is not an option: You [must] deliver as forecast reliably without fault. In this kind of work, the redefined work that we're talking about, failure is going to be pretty frequent. You're going to be constantly trying new approaches to problems and opportunities that have never been seen before.

Tanya Ott: It's almost baked into the concept.

John Hagel: Yeah, exactly. You've got to create an environment and leadership that encourages within that work group to say, “Look, you can fail, but the key is to focus on how are we going to accelerate performance improvement. So, fail, and learn from the failure, and then try something new to get to that next level. Don't stop there.”

Maggie Wooll: We hear a lot about the need to be lifelong learners or continuous learners. Redefining work in this way, and particularly redefining work and allowing people to work more often in groups to do this, this work really does become a platform for continuous learning. By taking on these different types of challenges and getting better at better at seeing what's not seen, figuring out new approaches to address it and trying to get closer to the customer, this is a real learning and growth opportunity for the workforce as well.

John Hagel: One key shift that this also implies is shifting our focus. The current discussion in the future of work is all about skills and reskilling. It's how do we give workers a new set of skills so they can continue to be productive. At one level, that's understandable because a lot of the work is being taken by the machine. But again, it's not rethinking the work itself. The way most people talk about skills, these are things that people need to accomplish something in a very specific environment. It could be how to operate this machine in this particular way or how to process this kind of paperwork. That's a skill. For us, what increasingly matters, and is not really on the agenda of most executives today, is what we call capabilities: Things that actually have value in any environment. It doesn't matter what environment you're in; if you have these capabilities you're going to have more impact. It's things like curiosity, imagination, creativity, emotional intelligence, social intelligence. Those are things that are essential to addressing unseen problems and opportunities in any environment.

One of the pushbacks we get, by the way, is this notion that, “Well wait a minute... creativity, imagination ... some of us are capable of that, but most of us just want to be told what to do and have a security of an income.” Our response to that is, let’s go to a playground and let’s look at children, six or seven years old, and show us one that doesn’t have curiosity, imagination, and creativity. We all have it as humans. The issue is that for many of us, if not most of us, it got crushed, first in schools and then the work environment where we were taught just to follow instructions. Don’t be curious. Don’t have imagination. But for us it's the metaphor of a muscle. These capabilities exist in all of us. If we don't exercise them, they atrophy. But they're still there. Given the right environment and the right encouragement, these capabilities come out very quickly and excite the workers and create value for the company.

Tanya Ott: John Hagel and Maggie Wooll have many more case studies in their article What is Work? You can find it at deloitteinsights.com. You can find us on Twitter at @deloitteinsight and I’m on Twitter at @tanyaott1. Thanks for tuning in today. See you again in two weeks.

This podcast is provided by Deloitte and is intended to provide general information only. This podcast is not intended to constitute advice or services of any kind. For additional information about Deloitte, go to deloitte.com/about.