The diversity and inclusion revolution: Eight powerful truths Deloitte Review, issue 22

22 January 2018

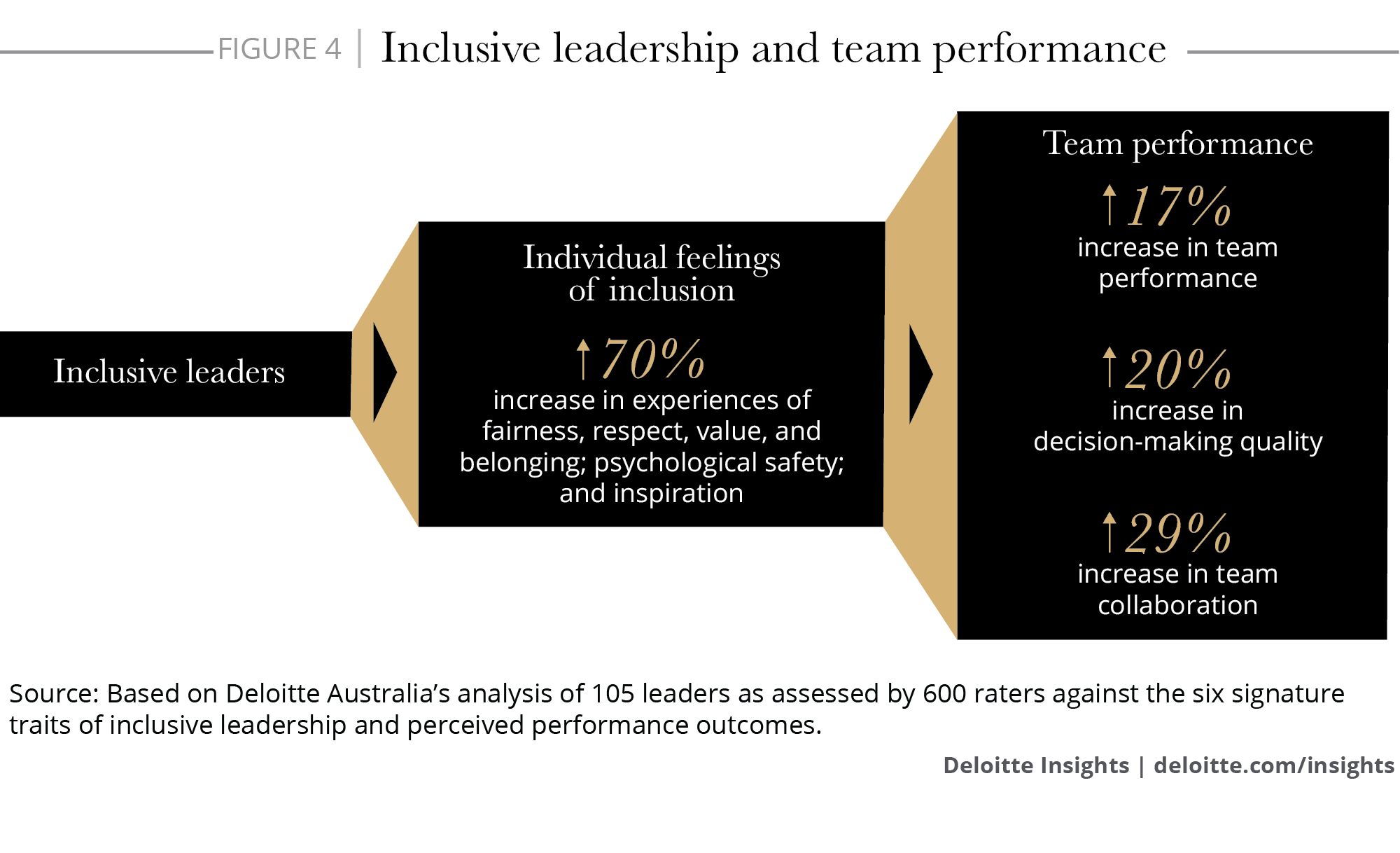

While most business leaders now believe having a diverse and inclusive culture is critical to performance, they don't always know how to achieve that goal. Here are eight powerful truths that can help turn aspirations into reality.

Diversity and inclusion as transformative forces

LEARN MORE

Explore the Future of Work collection

Subscribe to receive Talent content

Read Deloitte Review, issue 22

Create a custom PDF or download the issue

In 2013, Qantas posted a record loss of AUD$2.8 billion.1 This low point in the airline's 98-year history followed record-high fuel costs, the grounding of its A380s in 2010 for engine trouble, and the suspension of its entire fleet for three days in 2011 after a series of bitter union disputes. Across the country, predictions surrounding the fate of Australia’s national carrier were dire.

Fast-forward to 2017, and the situation couldn’t be more different.2 Qantas delivered a record profit of AUD$850 million,3 increased its operating margin to 12 percent,4 won the “World’s Safest Airline” award,5 ranked as Australia’s most trusted big business6 and its most attractive employer,7 and delivered shareholder returns in the top quartile of its global airline peers and the ASX100.8

Transformation is an overused word, but for Qantas it’s a perfect description. How did it happen? The company’s 2017 Investor Roadshow briefing sounded like a textbook in disciplined operational and financial management, as well as employee, customer, and shareholder focus. Yet for CEO Alan Joyce, the spectacular turnaround reflects an underlying condition: “We have a very diverse environment and a very inclusive culture.”9 Those characteristics, according to Joyce, “got us through the tough times10 . . . diversity generated better strategy, better risk management, better debates, [and] better outcomes.”11

Joyce’s insight reflects a growing recognition of how critical diversity and inclusion (D&I) is to business performance. Indeed, two-thirds of the 10,000 leaders surveyed as part of Deloitte’s 2017 Global Human Capital Trends report cited diversity and inclusion as “important” or “very important” to business.12 Despite this, overt attributions such as Joyce’s are scarce. Rarely does diversity and inclusion feature so centrally in a CEO’s story of success. The challenge lies in translating a nod of the head to the value of diversity and inclusion into impactful actions—and that necessitates a courageous conversation about approaches to date.

To accelerate that conversation, this document presents eight powerful truths about diversity and inclusion. It is the culmination of our work with approximately 50 organizations around the world, representing a footprint of more than 1 million employees. In this article, we draw upon the findings of seven major research studies that cut into new ground, covering topics such as diversity of thinking, inclusive leadership, and customer diversity.13 Our aim is to inspire leaders with possibilities and to close the gap between aspiration and reality.

1. Diversity of thinking is the new frontier

“The most innovative company must also be the most diverse,” says Apple Inc.14 “We take a holistic view of diversity that looks beyond usual measurements. A view that includes the varied perspectives of our employees as well as app developers, suppliers, and anyone who aspires to a future in tech. Because we know new ideas come from diverse ways of seeing things.”15

Apple’s insight lines up with Joyce’s. It’s about looking beyond demographic parity to the ultimate outcome—diversity of thinking.

This is not to say that demographic characteristics, such as gender and race, are not important areas of focus. Organizations still need to ensure that workplaces are free from discrimination and enable people to reach their full potential.

But there is a horizon beyond this.

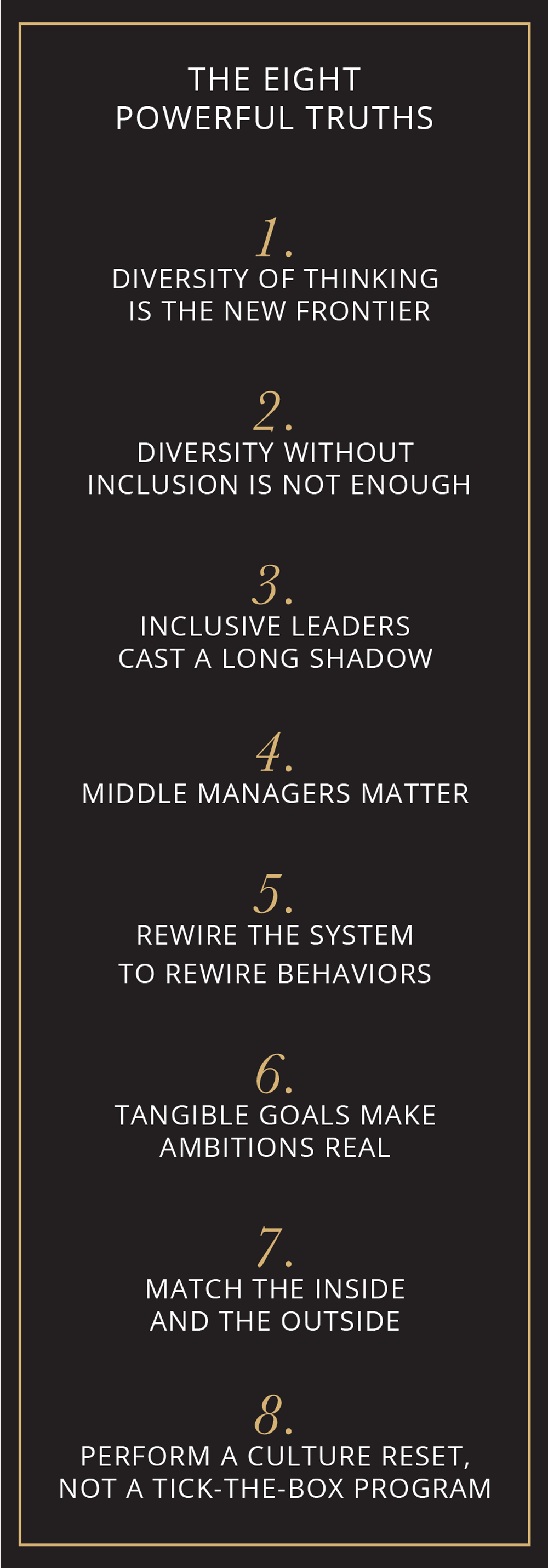

Our view is that the goal is to create workplaces that leverage diversity of thinking. Why? Because research shows that diversity of thinking is a wellspring of creativity, enhancing innovation by about 20 percent. It also enables groups to spot risks, reducing these by up to 30 percent. And it smooths the implementation of decisions by creating buy-in and trust (figure 1).16

So how can leaders make this insight practical, and not neglect demographic diversity?

The answer lies in keeping an eye on both. Deloitte’s research reveals that high-performing teams are both cognitively and demographically diverse. By cognitive diversity, we are referring to educational and functional diversity, as well as diversity in the mental frameworks that people use to solve problems. A complex problem typically requires input from six different mental frameworks or “approaches”: evidence, options, outcomes, people, process, and risk. In reality, no one is equally good at all six; hence, the need for complementary team members.17 Demographic diversity, for its part, helps teams tap into knowledge and networks specific to a particular demographic group. More broadly, it can help elicit cognitive diversity through its indirect effect on personal behaviors and group dynamics: For example, racial diversity stimulates curiosity, and gender balance facilitates conversational turn-taking.18

Diversity of thinking is powerful for three reasons. First, it helps create a stronger and broader narrative about the case for diversity, one in which everyone feels relevant and part of a shared goal. Second, it more accurately reflects people’s intersectional complexity instead of focusing on only one specific aspect of social or demographic identity.19 Third, a focus on cognitive diversity recognizes that demographic equality—rather than being its own end—is useful as a visible indicator of progression toward diversity of thinking.

The truth is, optimal diversity of thinking cannot be achieved without a level playing field for all talent, and clearly there is still work to be done on that front.

2. Diversity without inclusion is not enough

Deloitte’s research identifies a very basic formula: Diversity + inclusion = better business outcomes. Simply put, diversity without inclusion is worth less than when the two are combined

(figure 2).20

This insight is gaining traction, helping to position diversity and inclusion as separate concepts with equal importance. But there’s a problem. The definition of “inclusion” is often left to personal interpretation, and many organizations seem unclear about what it means. Without a shared understanding of inclusion, people are prone to miscommunication, progress cannot be reliably evaluated, leaders can’t be held accountable, and organizations default to counting diversity numbers.

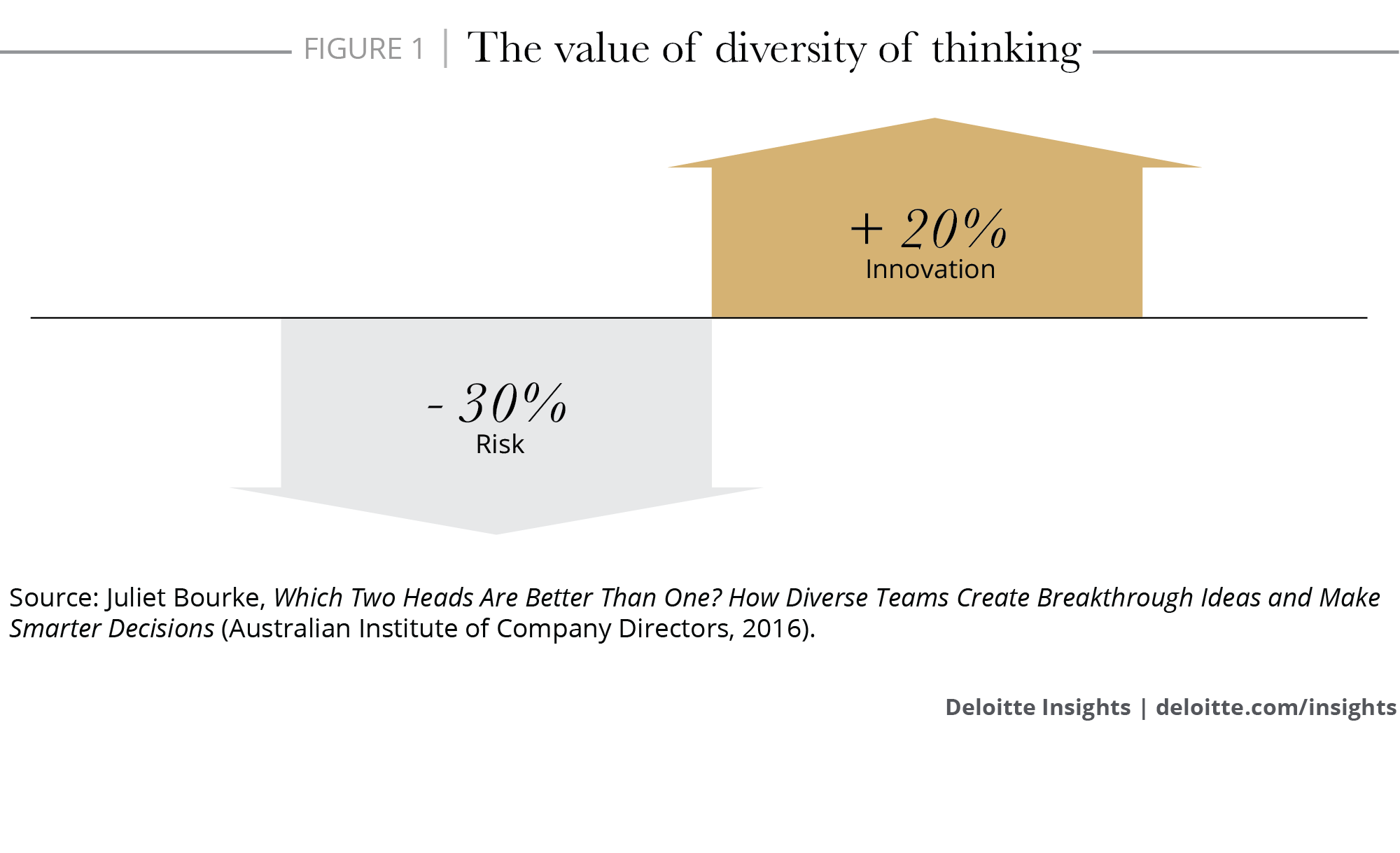

What does inclusion really mean? Deloitte’s research reveals that a holistic definition comprises four related yet discrete elements (figure 3).

First, people feel included when they are treated “equitably and with respect.” Participation without favoritism is the starting point for inclusion, and this requires attention to nondiscrimination and basic courtesy.

The next element relates to “feeling valued and belonging.” Inclusion is experienced when people believe that their unique and authentic self is valued by others, while at the same time have a sense of connectedness or belonging to a group.

At its highest point, inclusion is expressed as feeling “safe” to speak up without fear of embarrassment or retaliation, and when people feel “empowered” to grow and do one’s best work. Clearly, these elements are critical for diversity of thinking to emerge.21

The truth is that only when organizations are clear about the objective can they turn their attention to the drivers of inclusion, take action, and measure results.

At its highest point, inclusion is expressed as feeling “confident and inspired.”

3. Inclusive leaders cast a long shadow

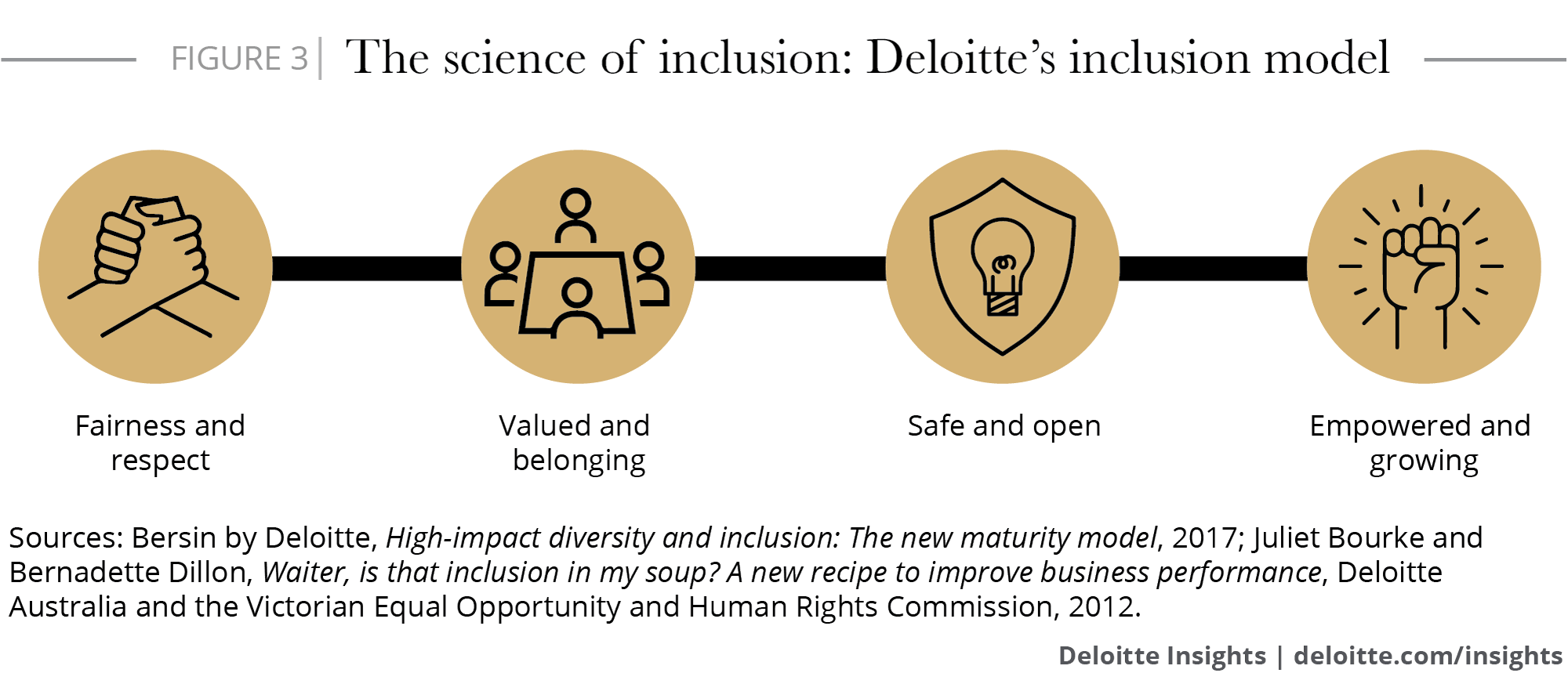

Deloitte’s research shows that the behaviors of leaders (be they senior executives or managers) can drive up to 70 percentage points of difference between the proportion of employees who feel highly included and the proportion of those who do not.22 This effect is even stronger for minority group members.23 Furthermore, an increase in individuals’ feelings of inclusion translates into an increase in perceived team performance (+17 percent), decision-making quality (+20 percent), and collaboration (+29 percent) (figure 4).24 Pause for a second to let those numbers sink in. This phenomenal difference reflects the power of a leader’s shadow.

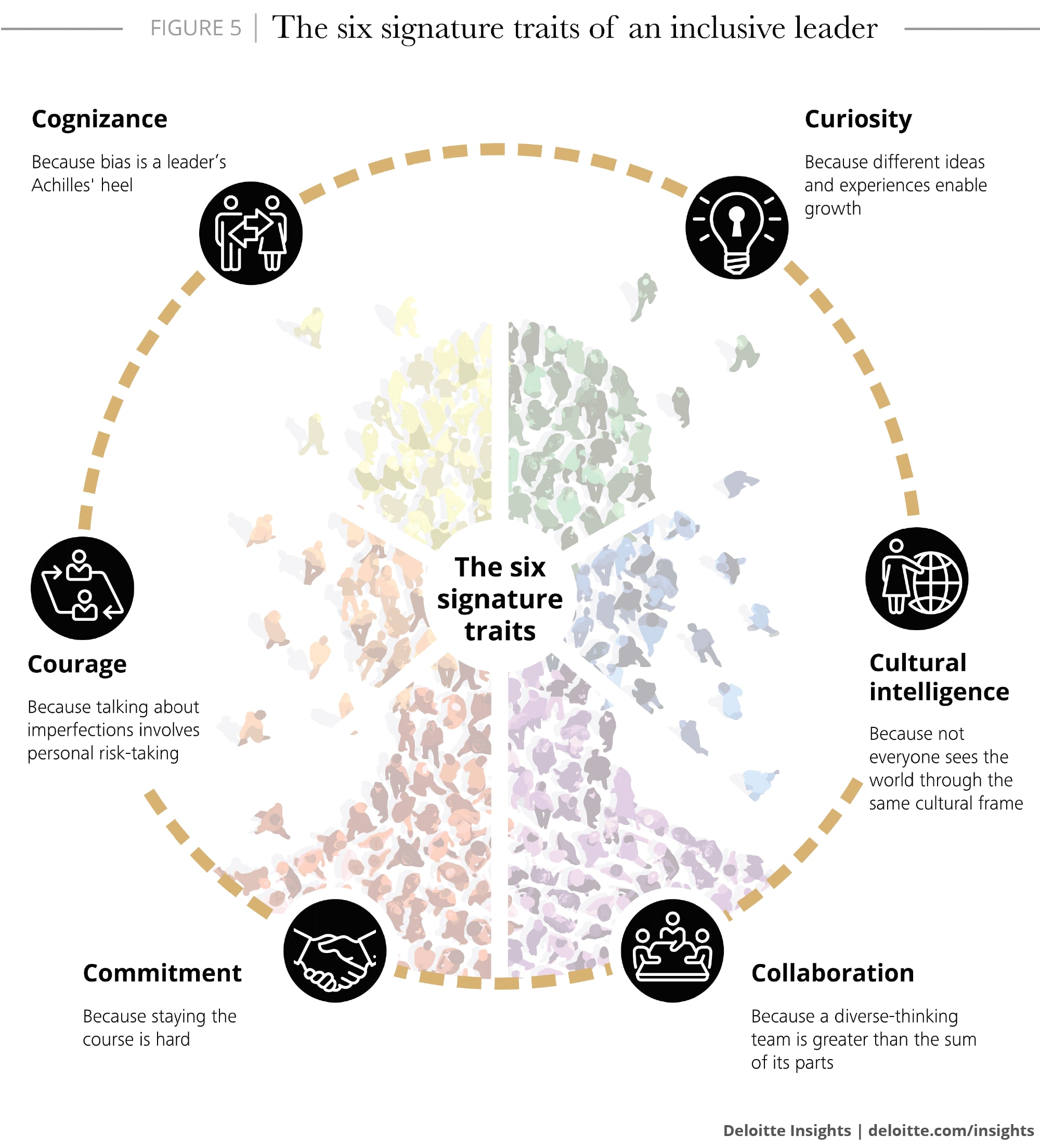

What distinguishes highly inclusive leaders from their counterparts? Deloitte’s research identifies six signature traits, all of which are interrelated and mutually reinforcing (figure 5):25

- Commitment: They are deeply committed to diversity and inclusion because it aligns with their personal values, and they believe in the business case for diversity and inclusion. They articulate their commitment authentically, bravely challenge the status quo, and take personal responsibility for change.

- Courage: They are humble about their own capabilities and invite contributions by others.

- Cognizance of bias: They are conscious of their own blind spots as well as flaws in the system, and work hard to ensure opportunities for others.

- Curiosity: They have an open mind-set; they are deeply curious about others, listen without judgment, and seek to understand.

- Culturally intelligent: They are attentive to others’ cultures and adapt as required.

- Collaboration: They empower others and create the conditions, such as team cohesion, for diversity of thinking to flourish.

Clearly, these traits are much more than just being “nice” to people, or even just being aware of unconscious biases. Our view is that inclusive leadership is broader and a much more intentional and effortful process. In essence, inclusion of diversity means adaptation. Leaders must alter their behaviors and the surrounding workplace to suit the needs of diverse talent, ideas, customers, and markets.

The truth is, the rules of the game have changed, and the old “hero” style of leadership is . . . old. As the context has become much more diverse, inclusive leadership is now critical to success.

4. Middle managers matter

“Ah, the middle managers conundrum,” the authors of a 2007 research paper wrote. “The grassroots are energized, the executives have seen the light, and the top-down and bottom-up momentum comes to a screeching halt right in the middle girth of most organizations.”26

This may sound harsh, but in the context of diversity and inclusion, middle management is a historically underserviced group. While many executives have been afforded time to learn, reflect, and debate, mid-level managers are often given directives. A change-management process that leaves questions unaddressed results in managers feeling unable to move forward.

To say this is problematic is an understatement. While change needs to be driven from the top, the middle manager cohort is vital to the success of an organization’s diversity and inclusion strategy. As Jonathan Byrne of MIT observes, “Regardless of what high-potential initiative the CEO chooses for the company, the middle management team’s performance will determine whether it is a success or a failure.”27

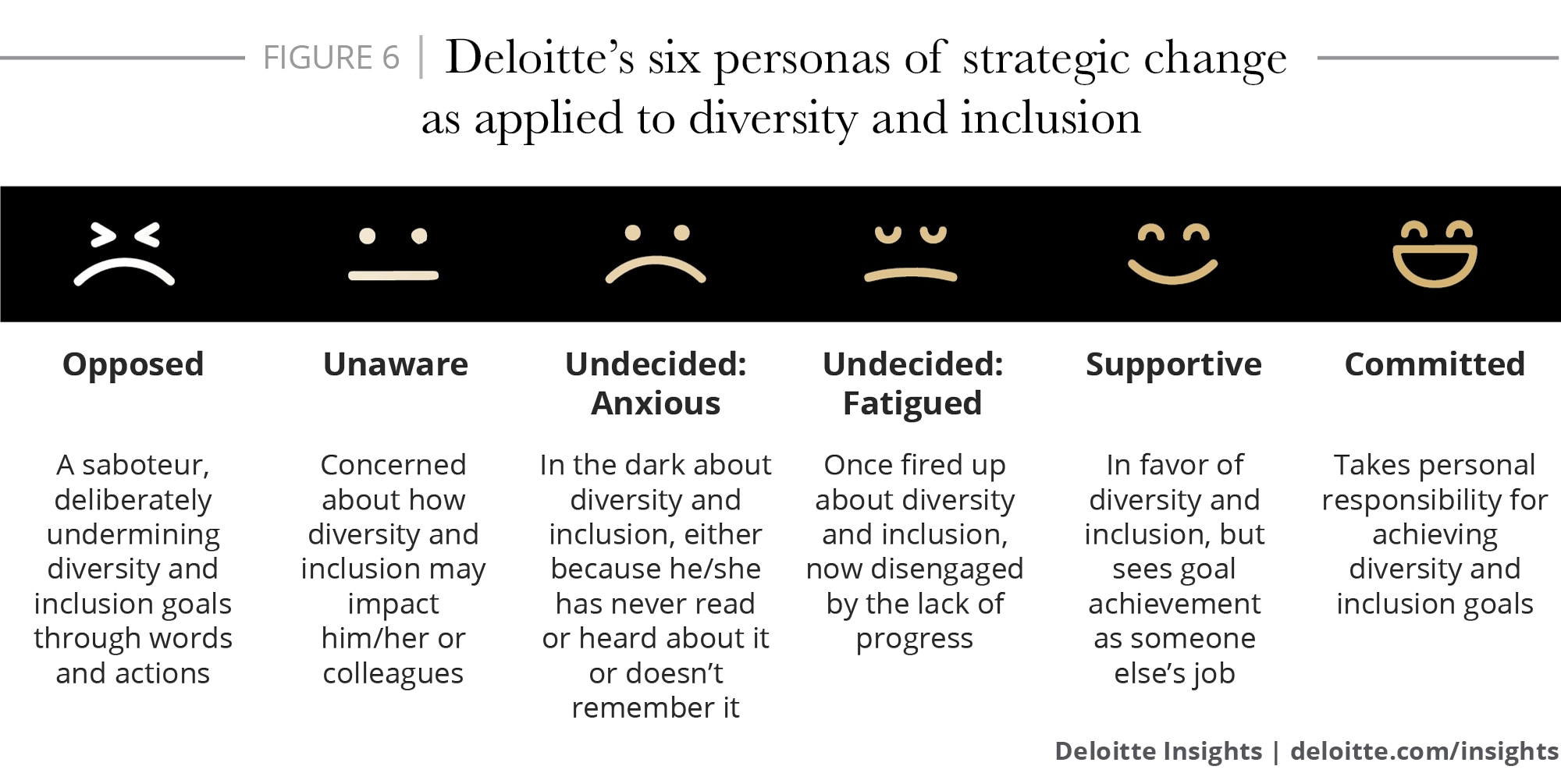

Clearly, organizations should engage middle managers. But when they do, they should also stop treating middle managers as if they are a single mass. Deloitte’s research identified six distinct archetypes, or “personas,” that individuals tasked with implementing change need to engage with and understand. These personas range from those who are deeply committed to those who can act as saboteurs (figure 6). Against that backdrop, one size will not fit all with respect to the way that information is delivered, experiences shaped, and boundaries set.

Senior leaders can influence middle managers in a variety of ways, including:

- Using storytelling to help move people emotionally and engage them on the purpose of the D&I agenda. For example, senior leaders could share their personal stories of commitment.

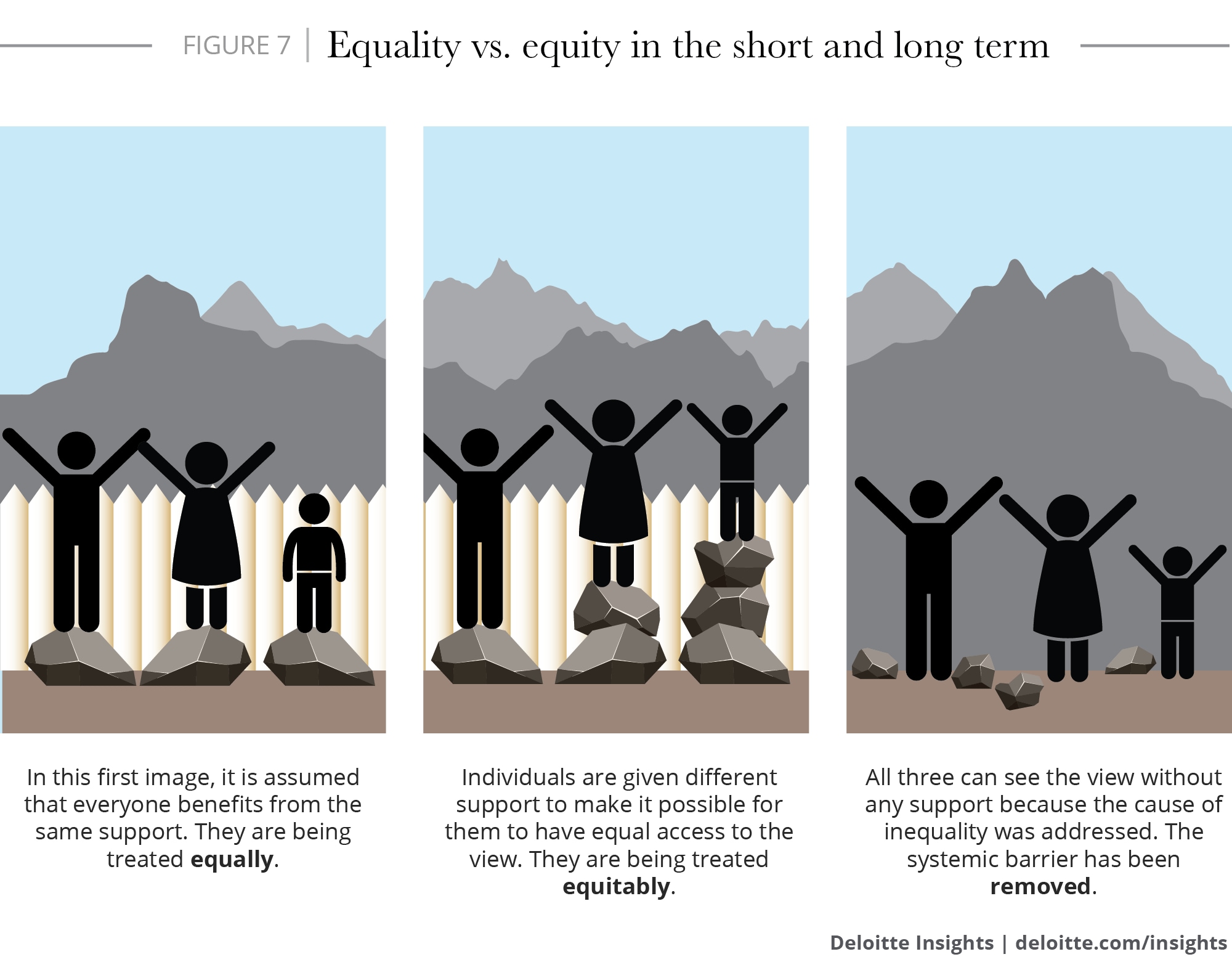

- Addressing myths and misconceptions by ensuring that middle managers understand the fundamentals—for example, by communicating the difference between equality and equity (figure 7).28

- Having open conversations to enable questions and concerns to be surfaced. Senior leaders should enter these conversations with curiosity and courage—two of the trademark characteristics of highly inclusive leaders.

- Exposing middle managers to influential role models and other powerful experiences, such as putting them on high-performing, diverse teams; presenting them with counter-stereotypic examples; offering them mentoring opportunities; and giving them experiences that put them in the minority. These tactics should help managers walk in someone else’s shoes and enable perspective-taking.

- Making tough decisions when needed to ensure that the organizations’ values are upheld. Inclusion is not a euphemism for “anything goes.”

5. Rewire the system to rewire behaviors

Training is the most popular solution to increase workforce diversity. Research shows that nearly one-half of the midsize companies in the United States mandate diversity training, as do nearly all the Fortune 500.29 Not surprisingly, the effectiveness of diversity training has come under scrutiny, with some claiming a positive impact (increased diversity representation), while others are dismissive (citing backlash and even activation of stereotypes).

Diversity training programs come in many shapes and sizes: educational vs. experiential, voluntary vs. mandatory, inspirational vs. shaming. At its best (voluntary, experiential, inspiring, and practical), training raises awareness, surfaces previously unspoken beliefs, and creates a shared language to discuss diversity and inclusion on a day-to-day basis. These objectives are a positive and important first step in the change journey.

However, when it comes to behavior change, training is often only a scene-setter. The more complete story is that, to change people’s behavior organizations need to adjust the system.

Why? First, biases can only be reduced rather than completely eliminated, and it is difficult to control biases that are unconscious. Second, biases can be embedded into the system of work itself, causing suboptimal diversity outcomes. Strategies to rewire the system make it easier to tackle biases and create a more comprehensive and sustainable solution.30

There are four steps to system rewiring:

- Using data to pinpoint leaks in the talent lifecycle. To do this, organizations can look at the profile of their employees from recruitment to retirement, coupled with data on inclusion experiences.

- Identifying and remodeling vulnerable moments along the talent lifecycle. These are points within specific talent processes where decision-makers are more susceptible to bias: for example, when decisions are discretionary and not subject to review.

- Introducing positive behavioral nudges, such as altering the default setting. In 2013, telecommunications firm Telstra introduced “All Roles Flex,” which made flexibility the starting point for all jobs rather than a special arrangement for some.31

- Tracking the impact. Periodically review diversity and inclusion data to assess the effectiveness of changes made.

When the BMO Financial Group,32 one of the 10 largest banks in North America, introduced an initiative based on these steps along with a communications and education campaign, it achieved significant impact. First, a record 83.5 percent of people managers voluntarily completed the initiative’s learning module within the first few months of its launch, signifying the program’s value. Second, there was an unprecedented year-over-year increase in employees’ perceptions of inclusion (+2 percent) and of having a “voice” at work (+2 percent). In addition, the hiring rates of minority group candidates increased by 3 percent in 12 months.

The truth is, rewiring the system is equally, if not more, important than retraining behaviors.

6. Tangible goals make ambitions real

When it comes to diversity and inclusion, nothing ignites greater debate than goals, targets, and quotas.33 On the one hand, the setting of specific diversity goals has been found to be one of the most effective methods for increasing the representation of women and other minority groups. On the other hand, contentious arguments about targets vs. quotas, accusations of reverse discrimination, and fears of incentivizing the wrong behaviors have arisen around goal-setting efforts.

Our view is that tangible goals are important. (By goals, we mean measurable objectives set by an organization at its own discretion,34 as distinct from dogmatic quotas.) However, their impact is tied to four conditions: communication, coverage, accountability, and reinforcement.

First, leaders should be capable of communicating confidently about what tangible goals do and do not mean. As Andrew Stevens, former managing director of IBM Australia and New Zealand, observes: “[Goals] don’t guarantee a woman a job or promotion. What they do is to increase the probability that a talented woman will be considered alongside a talented man.”35 This is done by prompting decision-makers to cast a wider search for candidates beyond their default comfort pool of talent.

Second, tangible goals should incorporate measures of inclusion, not just diversity. If diversity is the only metric, the organization misses half the story. Leading organizations know this. The financial firm Westpac, for example, not only measures diversity outcomes, but also uses the annual employee survey to test whether individual “people leaders” are committed to the creation of a diverse-thinking workplace.36 In the United States, facilities and food management firm Sodexo includes a diversity and inclusion competency in its performance management process, and 40 percent of a manager’s scorecard is devoted to inclusive behaviors.37

Third, tangible goals can only work when key decision-makers are accountable. By taking accountability for goals, leaders signal the importance of diversity and inclusion as a business priority and help focus people’s attention.

There has been an overemphasis on diversity, and an underemphasis on inclusion, as well as on the broader ecosystem of accountability, recognition, and rewards. The truth is, without appropriately crafted tangible goals, ambitions are merely ephemeral wishes.

Finally, tangible goals are most effective when combined with broader acts of recognition and reward. This powerful truth sits behind the success of global initiatives such as MARC (Men Advocating Real Change),38 the 30% Club,39 the CEO Action for Diversity & Inclusion,40 and MCC (Male Champions of Change)41—each of which implicitly recognizes the seniority and influence of its members. Conversely, there is embarrassment when leaders are called out for their organization’s poor diversity and inclusion track record.

Our view is that tangible goals have often been bluntly crafted and poorly communicated. There has been an overemphasis on diversity and an underemphasis on inclusion, as well as on the broader ecosystem of accountability, recognition, and rewards. The truth is, without appropriately crafted tangible goals, ambitions are merely ephemeral wishes.

7. Match the inside and the outside

In 2015, Samsung launched its “Hearing Hands” commercial. Built around a day in the life of Muharrem, a hearing-impaired man, it revealed a new world in which Muharrem’s neighbors engage with him for the first time in sign language, allowing him to feel much more connected to his community.42 In 2017, TV2 Denmark launched its “All that we share”43 campaign with a commercial that starts with the physical separation of people into line-drawn boxes based on stereotypical differences, and ends with a single larger group who now understands their shared points of commonality. That same year, Nike ran a commercial entitled “Equality,” which promoted the message that if diverse athletes can be equal on the playing field, they “can be equal anywhere” because “worth outshines color.”44

Each of these commercials went viral: 19 million views for Samsung, 4.5 million views for TV2 Denmark, and 5 million views for Nike. The question of why they were like cups of water spilled on dry earth underscores two compelling points.

First, customer diversity and inclusion have often been largely overlooked, with the lion’s share of attention devoted to employee diversity. And when customer segmentation is considered, it is more in terms of a customer’s financial profile than who customers are as people. As a consequence, services and products often reflect a stereotypical view of the customer. Lloyds Banking Group’s 2016 review of British advertising found that many minority groups were underrepresented in advertising, and only 47 percent felt that they were accurately portrayed.45 Similarly, Deloitte research from 2017 revealed that up to 1 in 2 customers from minority groups46 felt that their customer needs were often unmet over the past 12 months.47

Second, customers are becoming, and starting to lean into, a sense of empowerment; they communicate what they stand for with their wallets and social media shares, and messages of equality have a pervasive appeal. Deloitte’s 2017 research found that up to one-half of customers had been influenced to make a purchasing decision in the past 12 months because of an organization’s support for equality—whether around issues of marriage equality, gender, disability, age, or culture. The purchasers did not come only from the groups directly targeted by the message (such as the hearing-impaired in the Samsung campaign); they included anyone who felt that the message of equality had spoken to their personal values.

The truth is that while many organizations have prioritized workplace diversity over customer diversity, both are equally important to business success. Moreover, customers are often more ready to support diversity and inclusion than organizations perhaps realize. But a word of caution: This is not about vacuous marketing. Commercials that lack authenticity will be shamed by the very customers they seek to attract.

8. Perform a culture reset, not a tick-the-box program

Our final truth is the most sweeping and underpins all seven truths above: Most organizations will need to transform their cultures to become fully inclusive. While an overwhelming majority of organizations (71 percent) aspire to have an “inclusive” culture in the future, survey results have found that actual maturity levels are very low.48

What prevents the translation of these intentions into meaningful progress? Our experience suggests that organizations frequently underestimate the depth of the change required, adopting a compliance-oriented or programmatic approach to diversity and inclusion.49 For most organizations, change requires a culture reset.

This is no simple task. Cultural change is challenging irrespective of the objective, but it is perhaps even more so when the objective is an inclusive culture. Resistance is common: Those who are currently successful are likely to believe the system is based on merit,50 and change to the status quo feels threatening. Consequently, change toward greater inclusion probably requires more effort than many other business priorities. And yet it usually receives much less.

Workplaces have emerged as a venue in which these disparate pressures have manifested and become much discussed. Caught in the middle, workplace leaders around the world tell us that they feel ill-equipped to navigate these swirling waters.

So what does the path to an inclusive culture look like?

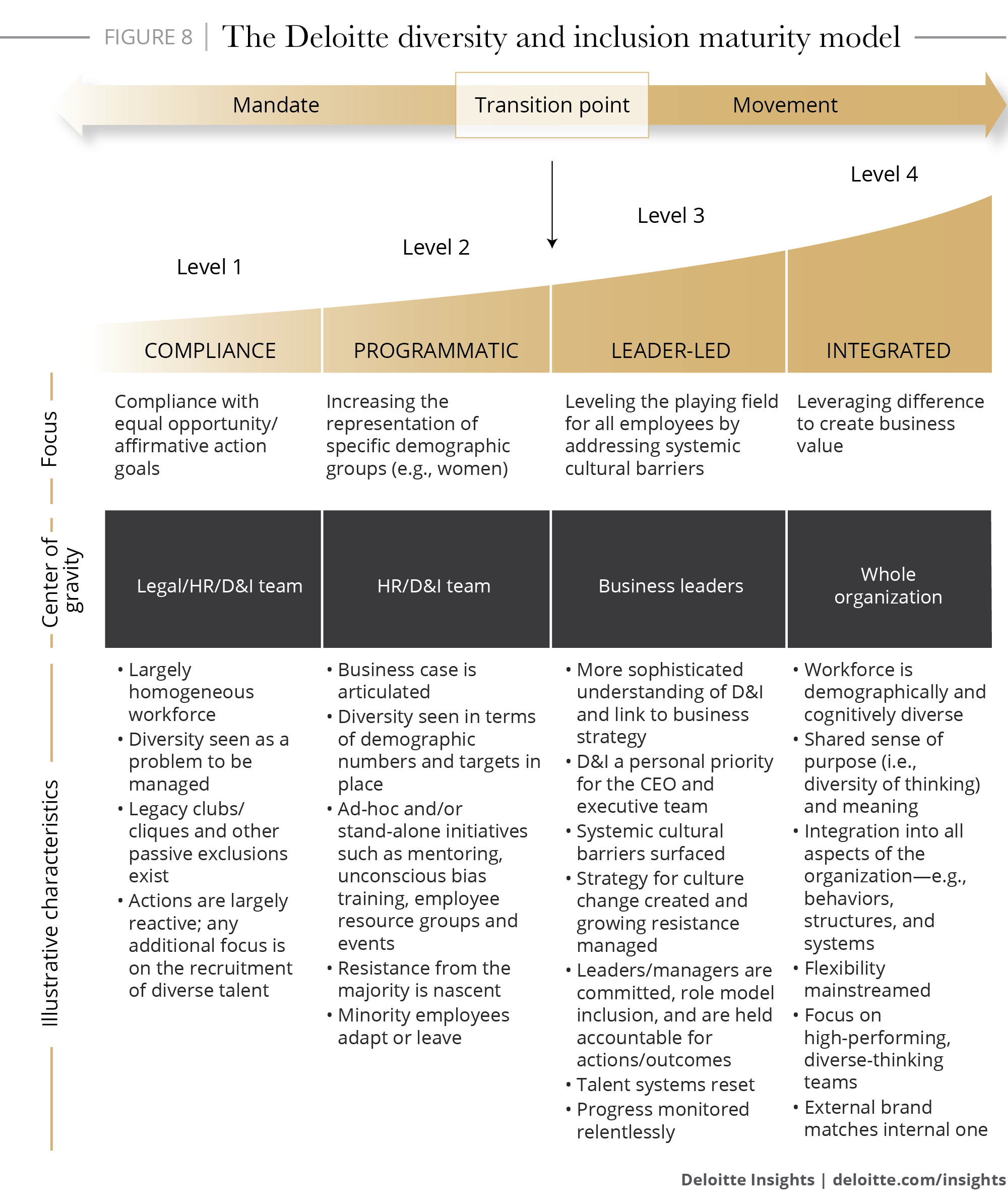

Deloitte research identifies four levels of diversity and inclusion maturity: (1) compliance, (2) programmatic, (3) leader-led, and (4) integrated (figure 8).51 Level 1 is predicated on the belief that diversity is a problem to be managed, with actions generally a consequence of external mandates or undertaken as a response to complaints. At level 2, the value of diversity starts to be recognized, with this stage often characterized by grassroots initiatives (such as employee resource groups), a calendar of events, and other HR-led activities (such as mentoring or unconscious bias training). At levels 1 and 2, progress beyond awareness-raising is typically limited.

More substantial cultural change begins at level 3—a true transition point—when the CEO and other influential business leaders step up, challenge the status quo, and address barriers to inclusion. By role-modeling inclusive behaviors and aligning and adapting organizational systems (for example, by tying rewards and recognition to inclusive behavior), they create the conditions that influence employee behaviors and mind-sets. Communications are transparent, visible, and reinforced. And at level 4, diversity and inclusion are fully integrated into employee and other business processes such as innovation, customer experience, and workplace design.

The truth is, significant change will not happen until organizations go beyond tick-the-box programs and invest the appropriate level of effort and resourcing in creating diverse and inclusive cultures.

Eight powerful truths, seven powerful actions

To borrow from Charles Dickens,52 this is the best of times and the worst of times to be advocating for diversity and inclusion. On the one hand, there is a groundswell of global energy directed toward the creation of workplaces that are more inclusive: 38 percent of leaders now report that the CEO is the primary sponsor of the diversity and inclusion agenda,53 and the formation of global initiatives speaks to the importance of these issues for the broader business community. On the other hand, some communities have become mired in divisive debates about equality (for instance, around issues related to sexuality, race, and religion).

Workplaces have emerged as a venue in which these disparate pressures have manifested and become much discussed. Caught in the middle, workplace leaders around the world tell us that they feel ill-equipped to navigate these swirling waters. Believing in the business case, but feeling time-poor and uncertain, leaders question what to say (and what not to say) as well as what to do (and what not to do).

To address these eight powerful truths, we propose seven powerful actions:

- Recognize that progress will take a culture reset

- Create shared purpose and meaning by broadening the narrative to diversity of thinking and inclusion

- Build inclusive leadership capabilities

- Take middle managers on the journey

- Nudge behavior change by rewiring processes and practices

- Strengthen accountability, recognition, and rewards

- Pay attention to diverse employees and customers

The truths we have presented challenge current practices, which are heavily weighted toward diversity metrics, events, and training. Our view is that the end goal should be redefined, cultures reset, and behaviors reshaped. Leaders should step up and own that change. Embracing these truths will help deliver the outcomes that exemplars have experienced. It will deliver the promised revolution.