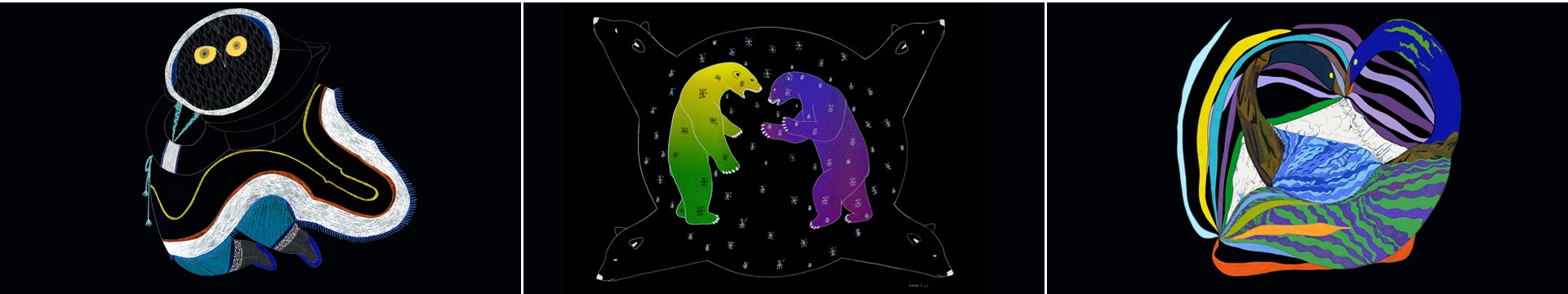

Colonization Treaties Climate action

Promises, promises

Can Canada meet its reconciliation and climate action commitments? We talked to Jason Rasevych, partner and national leader of Indigenous Services practice to find out.

December 2020 – The Government of Canada releases A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy, a new and improved climate plan laying out a framework to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030.

June 2021 – Bill C-15, an act respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, receives royal assent. This essentially means Canadian law will align with the UN declaration, which sets out a minimum standard for Indigenous peoples' survival, dignity, and well-being, covering issues such as self-determination and rights to their traditional lands.

Two moments in time. Two solemn commitments that will have a significant impact on the future of our country.

But many Canadians don’t realize that before we can fulfill these promises, we must first acknowledge the unique intersection between Indigenous reconciliation and climate action. Deloitte’s report— Promises, promises: Living up to Canada’s commitments to the climate and Indigenous reconciliation —does just this.

Jason Rasevych, a partner and the national leader of Indigenous Services, helps us understand and explore why advancing reconciliation is a powerful opportunity for Canada to tackle climate change at the same time.

Question: Why are Indigenous reconciliation and climate change fundamentally linked?

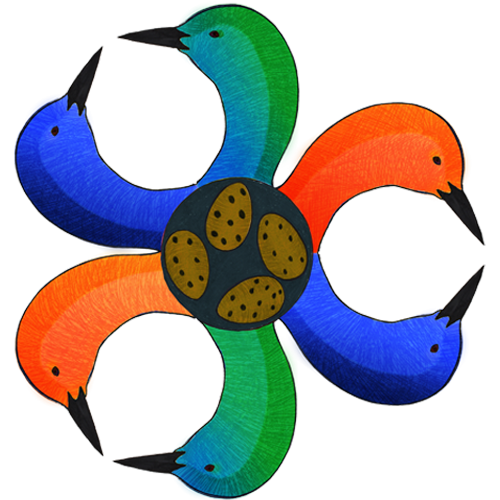

Jason: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples have lived on Turtle Island since time immemorial. As Indigenous peoples are the first inhabitants and peoples of the land, we have an ancestral and inherent responsibility to protect it. We have an intimate, spiritual, and cultural relationship with the land, air, water, and those who call it home.

Indigenous peoples have traditional knowledge and cultural wisdom. We’ve managed the lands and resources through a lens that looks at future generations, nature, humans, and economies as one. Reconciliation and climate change are linked because Indigenous free prior informed consent and social license will be required for approvals in natural resource development (oil and gas, forestry, mining), infrastructure development through traditional lands, and renewable energy development.

Q: What will happen tomorrow if we don’t act today?

J: Global warming will increase, natural disasters will evolve, destruction of lands and resources will occur at a rapid pace. Indigenous peoples will also feel the effects of climate change first and will be hit harder, since many continue to depend closely on the land for food, shelter, culture, and spiritual sustenance.

“Each and every one of us has a role to play in achieving our net-zero goals.”

Q: In developing this report, did you find anything particularly surprising that readers should know?

J: There’s a wide range of perspectives, but each and every one of us has a role to play in achieving our net-zero goals. There are many nature-based climate solutions and tools that we can use but we all need to be moving in the same direction. Many corporate boards lack the diversity in understanding the Indigenous aspects of ESG principles. The main challenge with ESG reporting frameworks is they fall short of disclosure requirements for corporations to report to shareholders, investors and regulators on their Indigenous relationships. The “I” for Indigenous is not just in the “S” of ESG but integrated throughout all aspects as Indigenous peoples have an inherent role as stewards of the land and sacred and spiritual connection to the land. We must do more to drive education in corporate boards to decolonize their corporate mindset to understand how to involve Indigenous peoples views to guide the values and decisions that impact Indigenous peoples lands and resources.

“Industry leaders make decisions based on a business case and regulatory and environmental impact assessments. But they often fail to address long-term or cumulative impacts of development.”

Q: Can you share a real-world moment that highlights this type of action? How are some of the affected communities responding?

J: One excellent example of nature-based climate solutions is the Great Bear Rainforest project in British Columbia, where the coastal First Nations are involved in carbon offsetting. This project helps Frist Nation peoples contribute to climate change mitigation by getting into an atmospheric benefit -sharing agreement with the BC government. This is a new pathway for those communities that wish to be involved in adaptive forest management and creating a system to reinvest into environmental monitoring and oversight that protects biodiversity, cultural values and traditional ways of life.

Q: The report briefly addresses the Seventh Generation principle. Can you elaborate a bit about this school of thought, and how it could help decision-making in the Canadian industries that are negatively impacting the climate?

J: This concept is about protecting the land, water, air, wildlife, and ecosystem by thinking through how any decision impacts the next seven generations. Many industry leaders make decisions based on a business case that is profit driven. The regulatory and environmental impact assessments often fail to address long-term or cumulative impacts of development. Integrating a long-term view and Indigenous traditional knowledge into decision making will help these leaders consider the short, medium, and long-term impact. Generational thinking will go a long way to limiting our footprint on Mother Earth.

Q: The report makes it clear that advancing reconciliation and reducing climate change must be done in tandem. But if I’m a Canadian business leader, where do I start my journey to achieve both?

J: Education and awareness of Indigenous peoples, communities, traditions, culture, customs, history, and legacy will be critical. Developing strategies for the company and individuals to learn about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Calls to Action, the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women inquiry, the residential school system policy, Indian Act legislation, impacts of colonialism, treaties, and cultural sensitivity and bias will be key. We are all treaty people, and we all have a role to play.

Q: What makes working with Deloitte on reconciliation and climate action unique?

J: Like all organizations, Deloitte is on a journey. We're trying to impact both areas—climate action and reconciliation—as they are aligned and non-partisan. Both issues are important to our network, clients, suppliers, and employees. We view our role as an integrator, helping the government, Indigenous peoples, and corporate Canada advance decision-making on these key issues.

Q: What are the areas of investment and innovation that organizations might be most interested in?

J: There are many—carbon offset accounting, decarbonizing industries, developing clean energy infrastructure, developing sustainable fuel, sustainability planning, goal setting for Indigenous relations and ESG consideration, renewable energy development.

Q: What’s the most important thing you hope people take away from reading this report?

J: Working together to take sustainable action is the way forward. It’s going to take 1,000 cups of tea—a concept I’ve learned from First Nation elders. The 1,000 cups of tea represent the time businesses need to commit to discussion and collaboration with Indigenous communities if they want to build a strong lasting relationship. So, let’s get started.