Perspectives

Reaching deep in low-income markets

Enterprises achieving impact, sustainability, and scale at the base of the pyramid

Research finds for-profit enterprises successfully serving low-income markets, achieving economic sustainability and scalability at the bottom of the pyramid.

Analysis: Depth of reach into the bottom of the pyramid, critical variables, and success factors

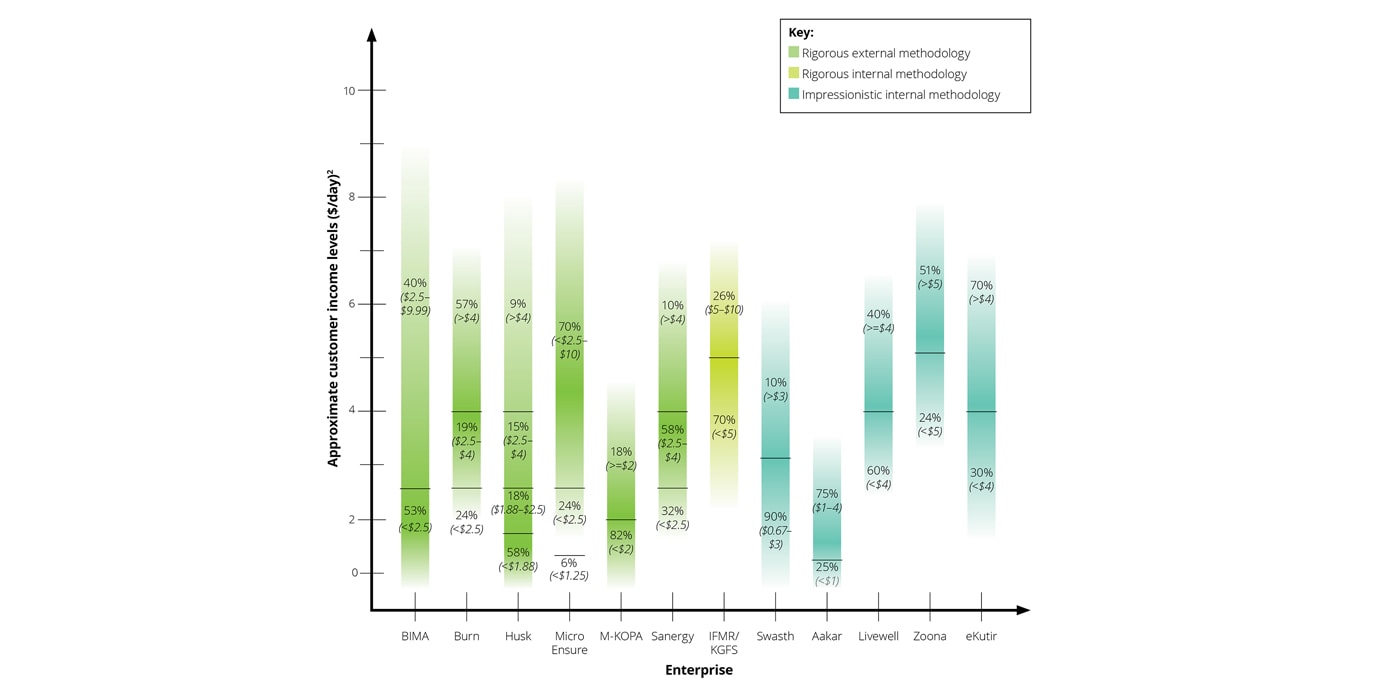

Enterprises seeking to achieve both impact and financial returns have worked hard for many years to deliver critical goods and services to those living at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP). While these efforts have clearly had tremendous impact helping large numbers of very poor people, it remains unclear how deeply down into the BOP we as a field are reaching.

Are these enterprises consistently reaching people living on $8 a day? How about $4, or $2, or less? Given the lack of good data, we really do not know. And yet we need to. In order to understand how to reach deeply down the pyramid, we need to understand who is successfully doing so. In order to know when we should subsidize for-profit enterprises to get them to reach lower, we need a better understanding of the “natural” limits to their current reach.

This report was developed jointly by Monitor Deloitte, the MacArthur Foundation, the Omidyar Network, and the Rockefeller Foundation to help provide transparency and guidance to advance the broader field of funding for businesses serving the deep BOP.

Reaching the BOP—Key report concepts and variables

Ability to reach deeply into the bottom of the pyramid to low-income markets—in an economically sustainable way—may be influenced by a few general conditions. Our analysis focused on the impact of these variables:

Asset-light vs. asset-heavy businesses: Asset-light businesses have low marginal costs and up-front capital requirements (e.g., a mobile phone app). Asset-heavy businesses carry a higher cost structure due to the need for physical presence, complex distribution channels, and a skilled labor force (e.g., a manufactured product).

Pull vs. push products: Highly valued products for which there is ready demand and that can be used immediately with little risk are pull products (e.g., food, electricity). Push products are goods and services with less obvious value or that provide uncertain benefits in the future (e.g., insurance, clean drinking water, mosquito nets).

While it is important to assess whether asset-light, pull businesses reach more deeply into the BOP, the reality is that much, if not most, critical development work entails asset-heavy operations, often delivering push products—access to health, education, clean drinking water, basic sanitation, life-saving vaccines and medicines, safer cooking methods, and so forth.

These asset-heavy, push goods and services face significant challenges: They typically must be manufactured or carried long distances, distributed through real property, delivered by skilled and expensive workers, sold via lengthy educational campaigns, and the like. The question then becomes whether there are conditions or variables which might mitigate these challenges, specifically broadening the customer income range.

Low-income vs. multiple income segments: We looked at whether or not having some customers at higher income levels (e.g., $8/day, $10/day) might help companies also reach lower income customers (e.g., $2/day, $4/day). Including higher income customers provide a larger number of prospective buyers, buyers who purchase more consistently and reliably over time, and less risk-averse buyers.

On the other hand, serving multiple income segments—segments with potentially different tastes, product preferences, desired price points, and modes of payment—could complicate business operations, driving up costs or detracting from an enterprise’s ability to reach lower down the pyramid through products and services tailored to the specific needs of the deep BOP.

Case study methodology

To assess the extent to which these three conditions help or hinder an enterprise’s ability to reach more deeply down the income pyramid, we opted for a case study approach. Through secondary research and interviews, we narrowed down a list of 100 plus potential case studies to a set of 20.

We recognize there are several limitations using a relatively small sample size for case studies, including over representation of enterprises that have lasted long enough to be studied (e.g., survivor bias), have volunteered to participate in the study (e.g., self-selection bias), and have made some effort to collect data on customers (potentially reflecting the maturity of the enterprise).

Our view is also taken in a dynamic market environment, where many of these enterprises live on the thin edge of profitability on a year-to-year basis. Despite these issues, we are confident that at this stage, given the paucity of available data, our case study approach is the most effective one available.

| Sector | Enterprise | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Aldeia Nova | Provides farmers with agriculture production inputs, and buys and distributes poultry and dairy farming outputs |

| eKutir | Operates a network of microentrepreneurs/kiosks that use technology to deliver inputs and sanitation solutions | |

| Education | FINAE | Provides loans to low-income college students through risk- and cost-sharing agreements with university partners |

| Urban Planet Mobile |

Provides affordable, basic English language instruction via mobile phones | |

| Energy (cookstoves) |

Burn | Designs, manufactures, and distributes fuel-efficient cookstoves for urban and peri-urban customers |

| Envirofit | Develops and sells fuel-efficient cookstoves (charcoal, wood, and LPG), stove accessories, and lighting products | |

| Energy (electricity) |

Husk Power | Designs, manufactures, and installs 25-250 kW “mini” power plants in villages and sells energy on a pay-per-use basis |

| M-KOPA | Manufactures, sells, and provides financing for solar home systems that provide electricity to rural households | |

| Off-Grid Electric | Manufactures, sells, and services solar electricity systems to rural and commercial customers | |

| Financial services | IFMR/KGFS | Provides financial products and services in rural areas through an adviser-driven wealth management approach |

| Zoona | Provides domestic and international money transfer via an agent network of 1,500+ mobile money transfer outlets | |

| Health | Aakar Innovation | Produces and sells compostable low-cost sanitary pads to low-income women via a female-led microenterprise model |

| Livewell Clinics | Operates a network of health clinics, focused on quality and efficiency, that serve as a “one-stop-shop” for primary care | |

| Swasth Foundation | Operates nonprofit health centers that provide high-quality primary health care services at half current market rates | |

| Housing | Echale | Offers an affordable and sustainable “self-build” housing solution and provides low-cost financing solutions |

| Patrimonio Hoy ((unit of Cemex) |

Provides market-based, do-it-yourself housing solutions to low-income families | |

| Insurance | ACRE Africa | Provides farmers microinsurance products that lower risk of investing in quality inputs, productivity, and access to loans |

| BIMA | Provides low-cost insurance and m-Health services via mobile network operators and financial service providers | |

| MicroEnsure | Designs and delivers affordable microinsurance with insurance companies, mobile network operators, and microfinance institutions (MFIs) | |

| Sanitation | Sanergy | Purchases, operates, and maintains a network of hygienic toilets; converts waste to agricultural inputs (fertilizer) |

Findings and implications

The most valuable findings for stakeholders actively seeking to reach the BOP include:

- Most enterprises we studied are able to reach BOP populations with critical goods and services and some are able to reach surprisingly deep (less than $2.50/day and in some cases $1.25/day).

- Many of the enterprises reaching the BOP and deep BOP are operating fairly successfully, both in terms of financial viability and growth.

- Being asset heavy and selling a push product does not necessarily prevent companies from reaching the BOP in a financially sustainable way; several have done it. Moreover, selling to customers across a broader range of incomes is clearly possible; the vast majority of our cases did so, and given its prevalence, this may be critical to financial viability and growth.

- Regardless of sector or products sold, enterprises can improve their chances for success by using a number of common business model design tactics to get more asset light, make products more preferential, or serve customers across a broader range of incomes.

- Most enterprises in our study received some form of subsidized capital, which was often very helpful in mitigating start-up risks as well as navigating the challenges inherent in BOP markets. It was often received at an early stage and then replaced by more market-rate capital, suggesting subsidy does not preclude businesses from eventually becoming self-sustaining.

- While all the enterprises we researched had an obvious social impact from the goods or services sold to BOP customers (access to finance, greater food security, etc.), these enterprises also yielded a number of less obvious development benefits (e.g., job and entrepreneurship opportunities, provision of public goods, improved resiliency of individuals and communities).

Based on our research, supporting for-profit enterprises that provide needed goods and services to the poor is a viable way to drive a development agenda. Our expectation going in was that it would prove very difficult for asset-heavy businesses selling push products to reach deeply down the income ladder to low-income markets (those living around $2–4 per day). Our research found the opposite: Asset-heavy businesses selling push products can indeed reach low-income markets in an economically sustainable way, at scale.

This said, many of these enterprises still seem to benefit greatly from, perhaps even require, some form of subsidy. With the exception of the asset-light business selling pull products, virtually every organization received a subsidy of some type, indicating such financial support may be critical.

Additionally, serving populations at somewhat higher income levels does not seem to prevent organizations from also reaching much lower income levels; given its prevalence, this also may be a near necessity. As such, grant makers and impact investors should not insist that all or most of an enterprise’s customers be at a certain level of poverty for that enterprise to be eligible for funding.

For-profit enterprises can be used to help deliver public goods and other services typically provided by government, including power, sanitation, health care, housing, and education. For governments and donors, these enterprises could be a useful supplement or substitute to government services.

Finally, governments and donors might consider investing in public education campaigns to promote certain product categories or services that benefit society overall. Any spending to get customers to buy one brand of a product category (or service) over another should of course be shouldered by individual organizations. But educating customers about the value of a product category (e.g., preventive health care, insurance, improved agriculture inputs, etc.) is a public good and can legitimately be taken on by government and other development organizations.

For more on our findings and areas of opportunity for further research, analysis, and support of enterprises serving the bottom of the pyramid, we invite you to download and read our full report.