Social business study: Shifting out of first gear has been saved

Social business study: Shifting out of first gear Findings from the 2013 social business global executive study and research project

17 July 2013

David Kiron United States

David Kiron United States Doug Palmer United States

Doug Palmer United States Anh Nguyen Phillips United States

Anh Nguyen Phillips United States- Robert Berkman

How do some businesses reap value from social business? What's holding others back? Learn what respondents think in results from a 2013 MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte social business study.

Learn more about Deloitte's social business initiative with MIT Sloan Management Review.

Key Findings

Seventy percent of respondents to the 2012 global executive social business survey conducted by MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte1 believe social business is an opportunity to fundamentally change the way their organization works. Yet many companies face meaningful barriers to progress. In our 2013 report, we delve into why some businesses are reaping value from social business, and what is holding others back. The following are our key findings:

Social Business Is an Immediate Opportunity

- The importance of social business is mounting. In our 2011 survey, 18% of respondents said it was “important today.” In 2012, the number jumped to 36%. The time horizon is also getting shorter. In 2011, 40% of respondents said that social “will be important one year from now.” In 2012 that number leaped to 54%.

- The importance of social is growing across all industries. Between last year and this year, respondents from all industry sectors increased the value they place on social business. None remained at the same level. None reversed course.

However, Progress Is Slow

- The emergence of socially connected enterprises isn’t fast. When asked to rank their company’s social business maturity on a scale of 1 to 10, more than half of respondents gave their company a score of 3 or below. Only 31% gave a rating of 4 to 6. Just 17% ranked their company at 7 or above.

- Companies are facing common barriers. Three major culprits are impeding progress: lack of an overall strategy (28% of respondents), too many competing priorities (26%) and lack of a proven business case or strong value proposition (21%).

Shifting Out of First Gear

- Companies are developing more mature social business capabilities by focusing on key business challenges. Businesses that have more developed social business capabilities don’t view social business solely as an application or tool. They have integrated it into many functions, such as strategy and operations, and use it in daily decision making. As a business solution, social has evolved, moving well beyond the marketing department, to address business objectives across the organization:

- 65% of respondents use social business tools to understand market shifts.

- 45% turn to it to improve visibility into operations.

- 45% leverage it to identify internal talent.

- Leadership support, measurement capability, content, and appropriate processes are must-haves for social business success. To spur and maintain the adoption of social, companies are systematically nurturing it. Company leaders are driving a conversational culture in very hands-on ways, including using social media themselves. Although the discipline of measurement is still evolving, more mature companies don’t let measurement challenges halt the progress. Successful social business efforts never skimp on content quality. Companies continually create it, curate it and keep it fresh to ensure participation. Finally, social business changes the way work gets done, and processes need to be designed to assure its adoption and success.

Shifting Out of First Gear

Introduction: An opportunity on the immediate horizon

In an interview for this year’s social business report, Gerald Kane, professor at the Carroll School of Management at Boston College, succinctly characterized where social business stands today: “Any new technology experiences a faddish hype cycle where people adopt it because they feel they have to,” he says. “With social, we are passing the peak of faddishness. Companies are starting to crack social’s code and turning to it for business advantage, intelligence and insight.”

In this second annual report from the MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte1 Social Business Study, we probed executives’ views of the social business opportunity and how companies are harnessing its value. The study included 2,545 respondents from 25 industries and 99 countries. It also incorporated interviews with nearly three dozen executives and social business thought leaders.

Echoing Kane’s observation, a key finding of the research is the rapid growth in importance of social to business. In 2011’s survey, 18% of respondents said it was “important today.” One year later, the number doubled to 36%. The time horizon of its importance is also shrinking. In last year’s report, 40% of respondents agreed that social would be important one year from now. In 2012, the number jumped to 54% (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

In the 2011 survey, 18% of respondents said social business was “important,” the highest possible level on a five point scale. In the 2012 survey, that number doubled to 36%.

What is Social Business?

We employ the term “social business” to describe an organization’s use of any or all of the following elements:

- Consumer-based social media and networks (for example, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, Google+, YouTube, SlideShare)

- Technology-based, internally developed social networks (such as GE’s Colab or the Cisco Learning Network)

- Social software for enterprise use, whether created by third parties (for example, Chatter, Jive or Yammer) or developed in-house

- Data derived from social media and technologies (such as crowdsourcing or marketing intelligence)

More Industries Are Getting On Board

The immediacy of the social business opportunity is growing across industries, another indicator of its move from faddish hype to business value. Between last year’s study and this year’s, respondents from all industry sectors increased the value they place on social business. None remained at the same level. None reversed course (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Respondents were asked to rank how important social business is to their organization on a five point scale. “Important” was the highest possible ranking. In 2012, most industry sectors had at least 25% of respondents agree that social business is important, reversing the results from 2011 when most industry sectors were below the 25% line.

While Media (entertainment, media and publishing) and Tech (IT and technology) continue to lead all industry sectors in the importance they assign to social business, other sectors demonstrated a marked increase in the value of social business. Of particular note is the Energy and Utilities sector. The number of managers in this sector who feel social is important surged from 7.1% to 29% from last year. Of the multiple factors driving the growth, this sector’s increasing efforts to engage with customers is the most significant. Pike Research estimates 57 million customers worldwide used social media to engage with utilities in 2011. Pike projects that number will jump more than 10-fold to 624 million by the end of 2017.2 While utilities currently use social media to resolve billing issues and provide information on services, they are expanding social media use to include crisis/outage communication, customer education (for example, information on recycling, renewable energy and energy efficiency), customer service, green energy promotion, branding and recruitment. Utilities are beginning to see the value of social listening to keep abreast of consumers’ interests. This is especially the case as new types of competitors enter the market, including solar power and energy management providers.

Market Drivers

Business leaders are keenly aware that social is becoming a primary tool that people use to share information and create knowledge. The consumerization of technology is making everything from tablets to smart phones as popular inside the enterprise as they are outside its walls. In addition, companies want their brands to be where their customers are — and where competitors already might be.

Social business is capturing significant business attention. McKinsey, for example, reported that social can create as much as $1.3 trillion in value in the four business sectors it examined (consumer package goods, consumer financial services, professional services and advanced manufacturing).3 Suppliers are covering all bases from marketing to social enterprise networking. In the social marketing software market, which includes a wide range of vendors from established players like Adobe, Lithium and Salesforce.com to a multitude of startups, Forrester predicts that the landscape “will look dramatically different in two years.” Leading vendors will partner and merge, and stragglers will be “swallowed or trampled by larger players from outside the social space.”4 In the enterprise collaboration software market, Gartner recently announced its revenue projection for team collaboration platforms and enterprise social software — $2 billion by 2016, with a notable five-year compound annual growth rate of 16.1%.5

But perhaps the strongest harbinger of social’s growth is the closing generation gap. “It’s not just young people or Millennials,” says Bill Ingram, vice president of analytics and social at Adobe. “It’s everyone, including grandparents who want to follow how their children and grandchildren are growing up.” Deloitte’s seventh annual State of the Media Democracy survey put hard numbers to the closing gap. The survey found that both Generation X and Baby Boomers see increasing value in social media: 81% of Generation X respondents and 70% of Baby Boomers see it as a powerful tool to interact with friends. And both generations have jumped on the texting bandwagon: nearly 80% of Generation Xers and nearly 60% of Baby Boomers see social networking sites, instant messaging and texting as an effective means to stay in touch.6 As the generation gap closes, businesses will find all age groups prepared to embrace social technologies.

Struggles With Social Business

Although the recognition of social’s importance is mounting, progress towards becoming a social business isn’t. The majority of companies we surveyed appear to be stuck in first gear. Our study found three major culprits holding back progress: lack of an overall strategy (28% of respondents), too many competing priorities (26%), and lack of a proven business case or strong value proposition (21%). Left unaddressed, these barriers can lead to daunting odds. Gartner estimates that 80% of social business projects between now and 2015 will yield disappointing results because of a lack of leadership support and a narrow view of social as a technology rather than a business driver.7

Nonetheless, some companies are poised to beat the odds. But they aren’t likely to beat them with one-size-fits-all enterprise transformations. Instead, businesses that assess themselves as more socially mature are building momentum by applying social tools and technologies to specific business challenges and assessing the impact. “Social is not an app nor a layer,” says J.P. Rangaswami, chief scientist at Salesforce.com. “Social is a philosophy and way of life that empowers customers and users.”

In this report, we delve into how some companies are bringing that philosophy to ground level — and what is holding others back.

Snapshot: The State of Play

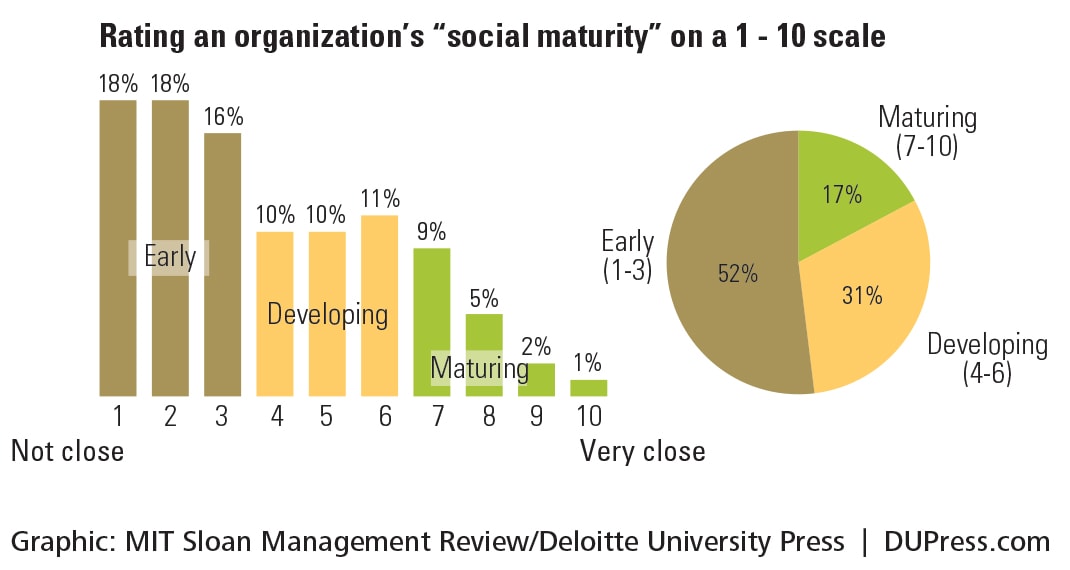

Despite the immediacy of the opportunity, the socially connected enterprise is emerging slowly. To assess that emergence, we asked respondents to evaluate their organization’s social business maturity along a scale of 1 to 10. Specifically, we asked: “Imagine an organization transformed by social tools that drive collaboration and information sharing across the enterprise and integrate social data into operational processes. How close is your company to achieving this ideal?” (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Figure 3

We asked respondents to imagine an organization transformed by social tools that drive collaboration and information sharing across the enterprise and that integrate social data into operational processes. Their responses reflect how close they believe their organizations are to that ideal.

More than half of the respondents — 52% — rated their organization at 3 or less. A scant 17% assessed their company at 7 and above. Moreover, in many organizations, social business is still an experiment: 44% of respondents indicated they are implementing an initiative in their departments, but more than half of these are pilot projects.

Dion Hinchcliffe of the Dachis Group describes “a trough of disillusionment” that businesses encountered with social media.8 He argues that social media was not originally intended for business use. It was created primarily by consumer companies looking for ways to better connect people. As a result, social media tools lacked the security, compliance and control capabilities businesses need. But the landscape is starting to change. “These requirements have made their way into the tools only in the past few years,” he says. “We are now at the point where the tools are starting to meet business needs.”

The point is well taken. However, our study discovered that there are statistically significant markers of success — and barriers to it.9 These markers correlate with social business maturity and go well beyond the business readiness of any technology. (See Figure 4.) For example, companies that are moving closer to the ideal of a socially networked organization share distinct characteristics. One significant characteristic is the integration of social into many business functions, including marketing, sales, IT and customer service. At Enterasys Networks, a mid-size network infrastructure and security company, 100% of employees have access to Salesforce.com’s Chatter product, and 80% use it to collaborate, share, and work across organizational boundaries and functions.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Practices that correlate with maturing social businesses.

Companies further along the maturity path also use social media technologies in daily decision making. The Cisco Learning Network, for example, is integrated with the company’s transaction systems, and the marketing team at Learning@Cisco uses data analytics tools to spot major trends and address customer requirements. More socially mature companies also avail themselves of a variety of social business tools and technologies, including media, software, data and technology-based networks.

Companies at the low end of the maturity spectrum share common hurdles. Lack of senior management sponsorship is significant. In businesses where support from senior leadership was lacking, respondents typically assessed their organization’s maturity a half point lower.

Lack of an overall strategy was also an influential barrier to progress. On average, feeling that their organizations lacked a clear social business strategy knocked nearly a third of a point off respondents’ assessment of the company’s maturity.

Taken together, the positive impact of management sponsorship and need for a clear strategy provide company leadership straightforward guidance on how to move the social needle. “It is incumbent on leaders to be intentional about social media and have a strategy for what they want to achieve with it,” says Michael Slind, co-author of Talk, Inc.: The Power of Organizational Conversation.

Divergent Paths to Social Maturity

There is no single path that leads to social business maturity. Company size plays a key role in determining the purpose of social business as well as how it matures. Among small companies (less than $250 million annual revenue), more socially mature organizations focus their social efforts on providing customer support, managing projects and accelerating innovation. According to our research, respondents from small companies that used social for any of these purposes rated their companies’ social maturity nearly half a point higher (on a 10-point maturity scale) than those that didn’t.

By contrast, larger organizations with more mature social capabilities leverage the entire analytical social business life cycle — generating social data, monitoring collection and integrating it into systems and processes. “The potential of social analytics is enormous,” says Sheila Jordan, Cisco’s senior vice president of communication and collaboration IT. “We capture and summarize major trends and communicate them to everyone from executives to engineers working on products in real time.”

More-mature large companies are also more likely than their less-mature counterparts to have a business case for social efforts. In fact, lack of a business case detracts considerably from the assessment of social business maturity at large companies. It cuts a half point. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Certain adoption factors measured in this year’s survey were found to correlate positively and negatively with social business maturity ratings. Regression coefficients for factors that meaningfully impacted both small and large firms’ social business maturity are listed above. Survey respondents rated their company’s social business maturity on a ten-point scale.

Dell’s Path to Social Maturity

Dell Inc. is a prime example of how companies can capitalize on social business opportunities and reach social business maturity over time. At Dell, social business began simply enough — a corporate blog. Seven years later, social is ingrained in its operations, and Dell now provides social business services to other companies. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Dell’s social business practice has evolved in many directions, often with senior leadership support.

As a company approaching social business maturity, unique aspects of Dell’s social business program stand out:

- Dell’s social activity extends beyond the marketing function. The company leverages social media to improve customer engagement, provide enhanced customer service and build products based on customer input through the company’s well-known IdeaStorm program started in 2007. The company extended IdeaStorm internally later in 2007, to help enhance productivity as well. IdeaStorm has led to the implementation of more than 500 new product ideas.

- Dell leverages the entire analytical social business life cycle — not only generating data, but monitoring and using it to make decisions. Building on the success of IdeaStorm, Dell realized that it needed to listen more carefully to the conversations among its customers in social media. In 2010, the company established a social media command center that helps it monitor online conversations in real-time and more deeply understand customer needs. In 2012, Dell enhanced its listening program, implementing social technologies that grab, sort and analyze vast amounts of digital conversations about Dell, its competitors and specific technologies. Applying natural language processing to more than 25,000 online mentions of Dell each day, the company translates that data into marketing strategy and customer service offerings.

- Michael Dell’s leadership has contributed to the company’s social business progress from the early stages to the present. According to Dell’s director of social media, Richard Margetic, “without Michael’s leadership, there’s no way we would have been able to become a social business.” Simply put, he says, “we wouldn’t have been able to get anything done.”

- The company’s social business strategies and direction are centralized, while its social media functions and teams are distributed and embedded across various functional units at Dell. In order to ensure the company is pursuing an agreed-upon direction and consistent strategy, the directors of each of these social teams meet weekly to work together cross-functionally. Richard Margetic brings together these directors and oversees the execution of the company’s social strategies, governance and policies.

Today, Dell Inc. has even set up its own consulting division to teach other companies how to be an effective social enterprise. Its Social Media Services Group trains other companies to develop better real-time customer insights, engage their audience and better understand their customers in the market. Not only does Dell show other companies what it has done, it also provides training for their staff on how to use and create these processes for themselves.

Shifting Out of First: Focus on Business Challenges

As Dell has proven, some companies are successfully shifting out of first gear. The evolution of social business has moved well beyond the early Facebook marketing forays seeking “Likes.” Our study found that companies with more advanced social capabilities are turning to them to:

- Understand market shifts (65% of respondents are planning to focus there to a great or large extent versus 14% for less socially mature companies),

- Improve visibility into operations (45% versus 5%),

- Identify internal talent or key contributors (45% versus 4%) and

- Improve strategy development processes (60% versus 9%). (See Figure 7.)

Businesses are following their own paths by using social business solutions to address problems that matter and by measuring the results. In this section, we move from the state of play to state of the art — current examples of social business applications.

Figure 7

Figure 7

More mature social businesses use their social capabilities to address important business objectives.

Marketing and Sales — A Sharper Edge

In our survey, respondents ranked sales second only to marketing as the functional area where social tools are used to a large or great extent. Social selling is becoming increasingly popular, and new tools are being developed to assist sales staff to use it in their work. However, social selling is about much more than using social media sites to generate leads.

We asked LinkedIn’s head of marketing for sales solutions, Ralf VonSosen, to elaborate on his company’s approach: “Social selling utilizes relationships and connections as well as insights that are available via social channels to facilitate a better selling and buying experience,” he says. “It’s really utilizing this fantastic social data to help us gain visibility and combine that with meaningful content we can share.”

The benefits of social selling are visible today. Consider the example of one global technology company we spoke with, which like many companies needs to sell more with less. Large enterprise sales are a complex matter in which sales people must make the case to decision makers and the myriad of influencers at the table. Traditionally, the process has been both costly and time consuming. To speed up the process and invigorate the quality of leads, this technology company developed a pilot program using LinkedIn’s social sales tool, Sales Navigator. With the tool, its sales professionals have access to all second- and third-degree connections of their fellow employees. Through that view into other companies and potential connections, the sales staff gains a deep understanding of potential clients and can reach out to decision makers and influencers through introductions and build credibility with meaningful content. By the same token, prospects can view the LinkedIn profiles of the company’s sales representatives to gauge the value of a potential business relationship, including seeing all of that company’s connections to their own organization.

In addition to measuring the number and rate of connections to assess its progress, the company has been using LinkedIn’s Social Selling Index,10 which ranks a company’s utilization of LinkedIn as a social selling tool. A three-month pilot of the new tool was completed in the spring of 2013, and the program’s numbers look promising. According to the data collected by the organization, the growth rate in unique connections with potential customers via LinkedIn grew by more than 200%, and the pilot team’s Social Selling Index increased more than 100%. Anecdotally, more than 75% of the 90 employees in the pilot have credited the tool with helping to achieve sales goals, and three sales professionals immediately purchased LinkedIn’s premium service out of their own pockets, rather than wait a matter of weeks for the company to purchase a long-term license for the broader team.

Morgan Stanley is using LinkedIn and Twitter to change the way its financial advisors acquire new clients and build their books of business. “We want to help financial advisors source new business in an easier way,” says Lauren Boyman, director of digital strategy at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management. “People reveal life-event information like promotions on social media that can be a gateway to a financially oriented conversation. Social also allows financial advisors to distribute content that enables them to build up credibility and eventually develop a trusted reputation based on their expertise.” Like many companies in highly regulated industries, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management had to work closely with its compliance organization. The wealth management organization also needed to provide financial advisors with a program that was easy to use. To meet both objectives, Morgan Stanley provides its tweeters and LinkedIn posters with pre-approved materials that are vetted to meet regulatory requirements.

The program was started as a pilot and moved out of pilot stage in June 2012. To measure the value, Morgan Stanley uses a monthly engagement scorecard. The scorecard tracks how many financial advisors sign up, as well as their behavior on the sites (i.e., how often they post or send invitations). The team also surveys the users to understand business impact. Of the financial advisors using LinkedIn and/or Twitter daily during the pilot, 40% had brought in new business from their social media usage. Perhaps the most compelling example: One advisor used LinkedIn to land a $70 million account.

Customer Service — A Step Change

Social offers new horizons for service effectiveness. For instance, companies are connecting with dissatisfied customers before their complaints spread and providing support wherever customers gather online. Businesses are also able to forge new connections between customers and use social analytics to understand needs and even moods.

One consumer product company is embarking on a step change in social’s application to service. The company has turned its staff and in-store representatives into social brand ambassadors to address everything from consumer complaints to questions about sunscreen.

For Facebook inquiries, for example, the company has set up chain of command including internal experts and store-based sales representatives. Each inquiry is assigned as it comes in. If no response has been given after several hours, the inquiry goes to the next person in the chain. Answers to common questions are archived for all employees to use.

“We leverage the knowledge of our internal experts to give customers informed advice,” says a company social media executive. “The customer is connecting with the expertise they need. If they want further information, we drive them to stores.”

Although the company measures consumer engagement in terms of clicks and online buzz, store traffic is an important metric. To capture it, the business offers coupons through social, blogs and partners. The coupons have unique codes so the company can measure the sales that come through its various online initiatives.

Operations — Precision and Visibility

The risk of supply-chain interruptions and delays is a common challenge in global business. For a pharmaceutical company, those risks involve more than dollars. They can put lives in danger if a product doesn’t ship on time. For the pharmaceutical company Teva, speed is of the essence, and rapid solutions to supply-chain issues are paramount.

Before Teva began to experiment with social platforms to solve supply-chain issues, resolving a problem could take weeks. And not solely because of the issue’s complexity. It could take a week or two just to schedule a meeting with all concerned. “Microsoft Outlook is a good tool,” says Nadine Jean-Francois, director of supply chain management. “But because people can book meetings so easily, they’re often double- or even triple-booked.”

To reduce the time drag, Teva created a social networking environment called Radar, using a Facebook-like tool where employees and partners can communicate in real time to address immediate challenges and build knowledge over the long haul. Users can collaborate, share data, comment on posts and blog about the issues at hand.

Measuring the direct impact of the social tool can be difficult, according to Jean-Francois. Although the cycle time for resolving supply-chain issues is getting shorter, process improvements are also part of the equation. But that also underscores a distinctive value of social business in more socially networked organizations — visibility into the specific operational issues the company faces.

Recruitment — Advantage in the Talent War

As the war for talent heats up, companies are ramping up efforts to beat competitors to the leading candidates. Covance, which manages clinical trials for pharmaceutical companies, is turning to social to fortify relationships with prospective candidates. “We have learned through years of traditional recruiting that people like to talk to others who do what they do,” says Lisa Calicchio, vice president of employee relations, global recruiting & diversity at the company. “They aren’t necessarily interested in speaking with a recruiter. They want to understand what their experience would be working here. The best people to answer those questions are the leaders in those roles.”

To build relationships between prospects and company leaders, Covance tweets. The recruiting organization works closely with marketing and communications to develop relevant content and draw potential recruits to its career website. For example, a Covance scientist might share research he or she is presenting at a conference. The tweet often generates new interest, and recruiters can reach out to new followers.

Once a potential candidate is in the fold, Covance sends text notifications when a position opens that matches the profile. The text includes a link for easy follow-up. “Mobile texting provides convenience that people really value,” says Calicchio. “It often works much better than cold calls or junk emails.” In terms of measurement, the company is still developing and relies on a combination of metrics and anecdotes. However, a telltale sign is resource efficiency and source of hires.

Innovation — Accelerating Top Management Buy-in

Concerns about innovation are constantly on the list of executives’ top concerns. The innovation process is often slow, and novel ideas are often watered down by the time they reach senior ranks. Electrolux tackled this challenge with an internal crowdsourcing event that filled a database with 3,500 new ideas and 10,000 comments on them — in three days. “The entire company was invited to join the innovation jam, and we had knowledgeable and skilled people to moderate and facilitate the event,” says Ralf Larsson, director of online engagement. “The leadership team was a big support and was out there building interest and asking people to join.”

To drive momentum during the three-day event, Electrolux created a scoreboard where participants earned rewards based on their activity. In addition, employees voted to select the top ideas, and three went immediately into the product development pipeline. “We may have come up with some of these ideas anyway,” comments Larsson. “But never with such speed, visibility and management buy-in.”

Plugging Into Other Technologies

The growth of social business innovation is forging new paths with media and other technologies. American Express, Nielsen, ConnecTV and Enterasys are cases in point.

American Express is leveraging Twitter with mobile phones and computers. In 2012, the company began offering statement credits to cardholders when they shopped at specific merchants including Whole Foods, Best Buy and McDonald’s. Either online or in-store with their mobile phone, the cardholder simply tweets a specific hashtag to activate the offer on the purchases they are making. “No one has ever offered anything like this before,” says Leslie Berland, senior vice president of digital partnership and development. “We have extended thousands of special offers, and cardholders have saved millions of dollars.”

The television ratings company Nielsen is leveraging Twitter to develop a more robust rating of television audiences. With its 140 million members, Twitter conversations add a deep dimension to any metric assessing audience size and engagement. The Nielsen Twitter TV Rating complements its existing ratings through real-time metrics about a program’s social activity, including the number of unique tweets associated with it.11

ConnecTV is capitalizing on the evolution of television from broadcast to social TV. A growing number of viewers are multitasking with phones and computers, giving rise to the second screen experience. Through an app, the ConnecTV AdSynch Network synchronizes a second screen through keywords on television as well as audio recognition technology that matches show, day, date, time and other television program attributes. The app provides viewers with the ability to get more product information or make a purchase in real time — all while the TV ad is running on the primary screen. According to a 2012 Nielsen report, 45%12 of U.S. viewers use a tablet daily while watching television, and 88% do so at least once a month. In addition, 27%13 are researching products related to commercials. Stacy Jolna, co-founder and CMO of ConnecTV, says that “amplifying and monetizing this new social TV behavior is the challenge.” ConnecTV provides both sides of the equation: companion content that syncs with the show to let viewers chat and share in real time on any second screen device, as well as a unique synchronization of TV ads that trigger a direct marketing experience, for the first time enabling viewers to see a product on TV and buy it easily and immediately. “That’s the future of television,” says Jolna.

Enterasys has embarked on machine-to-machine applications to provide better service to its business-to-business customers. In 2011, the company commissioned a team to develop Isaac, a social media translator that takes complex machine language and converts it into tweets, Facebook messages and chats. Isaac connects IT personnel to their networks for 24/7 monitoring with consumer devices and social media. “We have automated the entire front-end life cycle of the services interaction, machine to machine,” says Vala Afshar, chief marketing and customer officer at Enterasys. “For me, that has been the biggest ancillary benefit of becoming a social business — we started developing social machines.”

Shifting Out of Second: Spur the Effort

It may be tempting to believe that social media’s popularity outside the office will imbue efforts inside if the technology is right. Although there may be some initial enthusiasm, it can quickly vanish. To spur and maintain the adoption of social, companies need to nurture it in a systematic way. Businesses that are making the greatest progress toward becoming a socially connected enterprise focus rigorously on four interrelated areas: leading a social culture, measuring what matters, keeping content fresh and changing the way work gets done.

Leading a Social Culture

Although providing a tool may be a springboard for adoption, it is not enough. Company leaders must actively drive its use.

When Teva launched Radar to accelerate the resolution of supply-chain issues, for example, the project gained bottom-up traction because the tool added value to people’s jobs. However, whenever top management support faded, the effort quickly lost steam; with every change in top management, Jean-Francois found herself reaching out to the new leaders and bringing them on board in order to rekindle the momentum.

Furthermore, “[for] social collaboration to be successful in business, leaders have to explain the why,” says Michael Slind. “Leaders need to really collaborate and make sure people understand the importance of transparency, shared accountability — and sharing in general.” Connecting social with important business objectives is the crux of “explaining the why.” Morgan Stanley’s Boyman, for example, credits the head of sales for connecting social to business needs and assuring that the bank became a social business leader in its industry. “If I didn’t have the head of our sales force tell me that we have to be the first in the industry to do this, it never would have happened,” says Boyman. “Even when the project hit initial bumps because of the realization it would require IT dollars, he was still committed to keeping people focused and getting the needed resources.” Leadership also plays a pivotal role in creating a social business culture. American Express SVP Leslie Berland notes: “Does the company have leaders who are believers in what’s possible? That’s a big piece of the [social business] puzzle.”

At companies known for their social culture, such as Cisco and American Express, an open and collaborative culture is always in the room. “Cisco has a really open culture of transparency and trust,” says Jordan. “When you are working on driving successful business outcomes, you need to be in the middle of it with your colleagues, peers and customers at the personal level.” Leslie Berland emphasizes the importance of American Express’s collaborative team-oriented culture and how critical it is to drive social business initiatives. “I think it’s impossible to win in digital or in social media if you’re approaching it in a siloed way. And you can see it when you see different brands and companies and organizations launching things in the social media space, especially if there’s not alignment. It’s very transparent. It looks disjointed and not clear.”

However, lack of a vibrantly open and collaborative culture isn’t an insurmountable hurdle to the progress of social business. Teva, for example, operates in a highly regulated industry not necessarily known for open cultures. Yet that didn’t impede the course of their social program. “At first, people thought our internal collaboration was a finger-pointing tool that, unlike email, which is seen by a limited number of people, could expose one’s flaws or failings to many people,” says Jean-Francois at Teva. “But when they realized it was a different mindset, they started using it extensively.” Mark McDonald, co-author of The Digital Edge: Exploiting Information and Technology for Business Advantage, goes so far as to argue that although social communities don’t require extensive structure, managers are more comfortable when social business activities are structured. The presence of parameters, security measures and controls can ease their fears of the open-ended character of collaboration. With that comfort, leaders can take a strong role in driving a collaborative culture appropriate to the company and industry.

If the culture isn’t open, leaders may have to stimulate collaborative behavior themselves. At a global entertainment company, for example, an operations executive wanted to build a collaboration platform for marketing departments to share information about products and promotions in real time. The marketing heads, however, rarely shared information and voiced doubt about the value of participating in a shared data platform.

To overcome the doubt and cultivate support for the idea, the executive convened face-to-face meetings with the marketing leaders. By the end of the meetings, the group had started hammering out a process for collaborating together on the project and developing the new collaboration platform. After 18 months, they had put the protocols, processes and systems in place to capture social media data about customer reactions to various marketing campaigns across the enterprise. Insights from this collaborative effort led to the creation and adaptation of promotions and products in real time.

Creating collaborative behavior for social also means using it. Richard Branson of Virgin Airlines is famous for being a power user of social media. At Enterasys, Afshar and other executives actively participate in the company’s new social media channels. Without that commitment, Afshar believes social would have floundered. “It’s a fundamental equation,” he says. “No involvement by leaders, no commitment by employees. No exceptions.” (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Senior executives who responded to our survey believe social business can fundamentally change the way work gets done.

Measuring What Matters

Although the classic adage admonishes that what can’t be measured can’t be managed, businesses on the path to social maturity aren’t letting disagreements about the “best” measures halt their progress. While there is no consensus yet about how to measure returns from social business, some clear approaches and guidelines are coming to the fore.

Perhaps the most important: measurement must tie to what John Hagel from the Deloitte Center for the Edge terms “metrics that matter.” When seeking funding for a social initiative, for example, proposals should link the investment to what leaders are concerned about. To make the investment case, Hagel argues that when social business improves operating performance, the improvements can be leveraged to drive broad employee buy-in and momentum — and improvements in operating metrics lift the financial metrics for which business leaders are accountable. Once leaders see that link in action, they are likely to place greater value in social tools and technologies.

Linking social tools to operating and financial metrics poses a number of challenges. The fragmented use of social across an organization is a primary one. As Susan Etlinger, an industry analyst at the social business consulting group Altimeter, points out, “Each department has a different view on the value of the data that they are looking at. So as a result, it requires a fundamental shift in the way that companies gather insight and normalize it across different data sets and different departments.” Professors David Gilfoil and Charles Jobs of the DeSales University business program consider the issue in their article, “Return on Investment for Social Media”.14 The professors developed a three-dimensional framework to align different groups of metrics. Measurement programs need to address these three dimensions:

- Levels within the organization — corporate, departmental, individual — as well as industry

- Functions impacted — for example, sales, business development, R&D

- Appropriate and available metrics — for example, sales, costs saved or website visits

A simple example illustrates how the use of social tools links to operating and financial metrics. Imagine a manufacturing company is using social networking tools to improve quality control. Social usage measures, such as relevant posts on an internal collaboration site, can be tied to operational improvements such as reducing the time it takes to resolve a quality issue. Those metrics, in turn, drive financial performance measures, including revenue increases and cost reductions.

Although straightforward applications such as these can be found in many companies, the discipline of social business measurement is still in its early stages. However, several leading experts have provided some practical guidance:

Test and Learn. Etlinger points out that Nate Silver, political analyst and author of The Signal and the Noise, sees the need for companies to embrace testing and erring when working with data. To what extent companies can embrace such an approach depends on their measurement culture. However, even organizations without strong measurement cultures can move forward. Beth Kanter, an expert in non-profit performance measurement, stresses that companies should focus on incremental advances. Organizations launching a social initiative, for example, can start with one or two metrics tied to a business objective. After tracking these for a period of time, the company can build momentum by steadily adding new metrics and observing patterns in the data.

Measurement Programs Need Continuous Improvement. In 2013, the U.S. General Services Administration released its framework and guidelines for federal agencies to measure the impact of their social media programs. Justin Herman, social media lead at the Government Services Administration Center for Excellence in Digital Government, emphasizes that the framework is a “living document” that should be modified as new and improved ways to measure come to light. To spur the creation of those improvements, the metrics program is open not only to agencies, but also to tool developers and the public.15

Social Doesn’t Operate in a Vacuum. Companies should not worry that social isn’t the sole, or even primary, source of improvement. Hagel points out that even if other changes occur when rolling out a social tool, if the tool was a critical enabler of the performance improvement, management should credit it accordingly.

Finally, companies should not try to measure everything. As Cisco’s Jordan cautions: “If you try to measure every single thing you are doing, you will manage the ants while the elephants are storming by.”

Leaders Chart the Journey

Driving a social business culture begins with leadership. As part of our research, we studied a full range of companies at all phases of the social business journey. We discovered the common hurdles these companies face and what actions leaders can take to advance the effort.

| Barriers to Social Business Adoption: Companies face multiple common barriers implementing social business throughout all stages of the journey. | |||

| Stage 1: Early | Stage 2: Developing | Stage 3: Maturing | |

| Top 3 barriers to social business |

|

|

|

| Leadership Actions: Specific actions by corporate executives help their organizations address these common barriers. | |||

| Lead the strategy |

|

|

|

| Signal the importance of the medium |

|

|

|

| Have the right attitude toward measurement |

|

|

|

Social in the C-Suite

Our research found that while C-suite awareness of social media’s importance is on the rise, the perception of its most important value varies among the C-suite’s functional members.

CIOs are certainly involved. But as social business initiatives become more successful, chief marketing officers (CMOs) are playing a larger leadership role by capitalizing on digital technologies that enhance their oversight and leadership of social business efforts. Both CMOs and CIOs see a powerful future in social business: In our study, some three quarters of both of these C-suite respondents say that social business is an opportunity to “fundamentally change the way we work.”

CIOs are committed to staying involved and doing more. Our research found that the percentage of CIOs who say that social is important to their business more than doubled from 14% in 2011 to 38% in 2012.

Nonetheless, CIOs face barriers and constraints in maintaining their leadership roles in social business initiatives. The rapid growth in influence of marketing on technology initiatives and static CIO budgets is prompting analysts to question how far CIOs will be able to take the lead in social business. Hinchcliffe points out that some CIOs are being “pushed” into a different type of CIO role — the “Chief Infrastructure Officer.”

However, the evolution and opportunity in the C-suite may be greater collaboration between the CIO and CMO. Adobe’s Bill Ingram says that, “what we’re seeing in the market is a real partnership starting to evolve between the IT and marketing organizations.” He also points out that IT can take on matters such as ensuring the site is up, apps are running, metrics are solid, and the infrastructure is well-managed. Marketing, on the other hand, can manage the content. Ultimately, according to Ingram, this division can help eliminate technology as a limiting factor for marketing; the new partnership lets IT do their job, and marketing can now do their own job faster.

At the same time, the new role of chief digital officer (CDO) is emerging in the C-suite. While the specific responsibilities vary, CDOs can provide broad leadership and attention to key digital initiatives. Afshar says that because the CDO will be the person aligning the social strategy with the hottest areas impacting the business, he or she could occupy “the most powerful role in the company.” Today there are many well-known organizations in a wide range of industries — both for-profit and non-profit — that currently employ a chief digital officer. Among them are Gannett, NBC, Simon & Schuster, Starbucks, Columbia University and Harvard University.

| CEO | CFO | CIO | CMO | |

| 1st Top Use of Social Business | Driving brand affinity | Increasing sales | Managing projects | Driving brand affinity |

| 2nd Top Use of Social Business | Increasing sales | Recruiting and managing talent | Driving brand affinity | Increasing sales |

| 3rd Top Use of Social Business | Crowdsourcing ideas and knowledge | Providing customer service | Providing customer service | Crowdsourcing ideas and knowledge |

Creating and Curating Meaningful Content

When CARA Operations, the Canadian restaurant franchisor, wanted to bolster the morale of its wait staff and focus on customer experience, it launched a reward program through Facebook where managers and restaurant staff could congratulate others for innovative efforts beyond the call of duty. After much planning and promotion, Staff Room was launched with great expectations — and then quickly fizzled. The problem, explains CIO Natasha Nelson, was a lack of dedicated resources to manage the program and regularly update it with new content. She says that the company thought that the program would grow organically, but “in hindsight, we see having a dedicated resource to manage the program would have helped to seed the system with the meaningful content that would have driven people to the site on a regular basis.” Having such a resource, Nelson says, would have “yielded a much higher level of adoption.”

Successful social business hinges on quality of content. And with the greater use of social comes much stronger demands for fresh, unique content. “We are entering the stage of social fatigue,” comments Ray Wang, CEO of Constellation Research. “Content has to be more relevant and in the context of a relationship, location, project and time.”

To overcome social fatigue, many companies devote considerable resources to content development. A 2013 study by Gartner, for example, found that nearly 50% of social marketing teams believe creating and curating content is their top priority.16 Coca-Cola is a prime example.

After becoming the first retail brand to exceed 50 million Facebook likes, Coca-Cola is shifting its marketing focus from creative excellence to content excellence — generating a steady flow of content that average social media users will feel they have to share. The goal is to create conversations with consumers by shifting from one-way storytelling to dynamic storytelling across many social media platforms.

Coca-Cola’s emphasis is on new content and applies a 70/20/10 investment principle to its creation: 70% of the content created is low-risk marketing, which consumes half their time. Another 20% feeds off ideas that already work and reinventing them to see what can be achieved. The final 10% is high-risk content marketing. When a high-risk effort pays off, it can fuel the content strategy anew.17

Relevant, timely and accurate content is also paramount at Cisco and drives what the company calls its “front” — the Cisco Learning Network. Over five years, the network has grown from 600,000 to more than 2 million users. It is charged with creating the next generation of Cisco customers by providing learning tools, training resources, and industry guidance to anyone interested in an IT career through Cisco certification. The network also provides a venue for gathering and discussing the company, its product lines, and the industry overall.

Relevant, quality content is central to the network’s success, according to Jeanne Beliveau-Dunn, vice president and general manager of Learning@Cisco. Without the initial content that Cisco seeded into the system, the Cisco Learning Network would not have taken off. “The content is what separated the Learning Network from other collaboration tools such as Facebook,” she says. “The content drives an organic community toward Cisco-specific conversations.” Given the practical reality of the community’s size, Cisco realizes that it can’t create all the content. Often, it takes the role of curator. But Cisco keeps the content fresh. “If you are trying to create community and you are lifting and shifting content, you are wasting your time,” says Beliveau-Dunn. “You don’t want to take what was stale and try to make it prettier. The key is identifying the interesting and relevant content that meets the needs of your audience and making it easy to find and digest.”

Changing the Way Work Gets Done

From responding to markets to fostering internal knowledge sharing, achieving social’s impact means changing the way work gets done. “Social is about using technology in a more thoughtful and broad-based way to meets business needs in a social context,” says Hagel. “It is front and center to the question: How can and should people connect to advance business objectives?”

Companies can change how the work is done by revamping processes and embedding social capabilities into workflows. This process — what we call social business reengineering — can break down barriers that hamper people’s ability to find the right information and work effectively across functions.

Social business reengineering is a planning process that moves systematically from strategy to technology.18 It begins by identifying natural groups of stakeholders who will see value in connecting in new ways — for example, linking R&D to marketers, product engineers and sales teams. With these stakeholders in mind, the process turns to the “who” and the “what” — the key players, business objectives and incentives that will garner social business buy-in and usage. Company leaders then need to identify any barriers to adoption and have a plan in place to remove them. Once these elements have been figured out, the company can identify the most appropriate tool for the job.

Dell is a prime example of social business changing the way work gets done. The company’s IdeaStorm platform is one of several initiatives where social business drives the way the company operates. In essence, IdeaStorm is a public suggestion box where customers can provide input on products and features. But the similarity ends there. As the company listens to the market, it identifies opportunities to refine product features. It then reaches out to the customer community and works with it to identify the specific requirements. “We begin by listening,” says Richard Margetic, Dell’s director of global social media. “We then work with the customers who are most active in the conversation and drive to a product launch.”

Reading the Signposts

Companies want to chart their social business progress, both in terms of their capability and that of their competitors. However, social business adoption is uneven, making progress difficult to track and monitor. In his research, Hagel found three common adoption patterns.i The first is under the table: teams using social software on their own to help their efforts. Ad hoc approaches are a bit more visible. For example, executives may see an opportunity for social and leverage it in his or her part of the organization. Finally, some efforts get a green light when senior executives “check the box,” acknowledging the importance of social but without a deep understanding of its value.

Although adoption is uneven, Wang has identified signposts that signal how an organization is progressing. He sees five stages — Discovery, Experimentation, Evangelization, Pervasiveness and Realization — and outlines these markers of progress from one to the next:

From Discovery to Experimentation: When an organization identifies an outcome to achieve

From Experimentation to Evangelization: The experiment in one department or division becomes the model of similar experiments in other parts of the organization

From Evangelization to Pervasiveness: The number of projects proliferates, creating a demand for context and relevancy in response to an explosion of information

From Pervasiveness to Realization: When an organization establishes governance to address disruptive technologies and business-model change

Companies shifting out of first gear are finding value from their social business efforts. Many realize that their companies need to be where their customers are, and they are using social business to tackle everything from sudden market shifts to the war for talent. McKinsey estimates that the global dollar worth of social business activity will be measured in the trillions. We found that executives see that value and immediacy.

Yet companies nonetheless face formidable odds. Gartner estimates that 80% of social initiatives will not meet expectations. In this report, we probed how companies stuck in first gear — or looking to boost mature efforts — can steer clear of Gartner’s prediction.

Focusing social business on business challenges is the key lesson learned. Companies that are successfully shifting out of first gear don’t view social as “an app” that will thrive at work simply because it thrives outside the office. These companies use social to address specific issues and define a role for social business in the solution. Be it tackling supply-chain issues or driving higher-octane innovation, success is about leveraging a business tool — not a technology.

Focusing on business challenges, however, is only part of the equation. To spur the effort, company leaders are cultivating new modes of communication and new patterns of dialogue. Sometimes that means modeling the behavior long before the tool is launched. Measurement is also critical. An effective measurement mindset, however, focuses on measurement that matters. Although the discipline of measurement is evolving, successful social initiatives don’t make the great the enemy of the good. Social business success is also about generating and sustaining content. Whether it is created or curated, its freshness is the draw and the glue that holds the effort together. Finally, social business changes the way work is getting done, by reengineering processes.

In the time it took to read this report, millions of tweets have been posted to Twitter, tens of millions of new postings have appeared on Facebook, and thousands of hours of new video are streaming from YouTube.19 Social media is evolving rapidly — and that evolution is changing the face of how businesses work and compete.

Appendix

The Survey: Questions and Responses

Results from the 2012 Social Business Global Executive Survey

About the Research

To understand the challenges and opportunities associated with the use of social business, MIT Sloan Management Review, in collaboration with Deloitte, conducted a second annual survey of 2,545 business executives, managers and analysts from organizations around the world. The survey, conducted in the fall of 2012, captured insights from individuals in 99 countries and 25 industries and involved organizations of various sizes. The sample was drawn from a number of sources, including MIT alumni, MIT Sloan Management Review subscribers, Deloitte Dbriefs subscribers and other interested parties.

In addition to these survey results, we interviewed 33 business executives and subject matter specialists from a number of industries and disciplines to understand the practical issues facing organizations today.

Their insights contributed to a richer understanding of the data. We also drew upon a number of case studies to further illustrate how organizations are leveraging social business.

Percentages in exhibits A, B, E, F, G, H, J do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.