Public sector, disrupted: How disruptive innovation can help government achieve more for less has been saved

Public sector, disrupted: How disruptive innovation can help government achieve more for less Part of a Deloitte series on innovation

22 March 2013

Governments around the world need to “do more with less” in the face of deep austerity measures. Disruptive innovation can help governments reduce costs while maintaining or even improving services.

Introduction

Introduction

With governments everywhere facing a sea of debt as far as the eye can see, taxpayers have been presented with a very unappetizing choice between higher taxes or radically curtailed public services—or, ever more often, both. This paper proposes an alternative path—a way to use innovation to make public programs radically cheaper without slashing services; a way to break the seemingly unavoidable trade-off between paying more or getting less. In short, a way to achieve that most elusive goal: getting more for less.

Outside of the public sector, we’ve grown accustomed to steadily falling prices for better products and services.

Access to a car on a Saturday used to cost upwards of $100. Because most rental agencies were closed on the weekend, you had to rent for several days even if you only needed it for a few hours—and then purchase insurance and gas. Car sharing companies such as Zipcar now allow urban residents to rent a car for as little as $7 an hour—insurance and gas included.

Airline travel was once largely unaffordable for many business travelers and most families.1 Then along came Southwest Airlines and other low-cost carriers, and now air travel is often cheaper than taking the train.2

The doubling of computing power every 18 months, known as Moore’s Law, results in reduced computer prices of about 6 percent and improved performance of 14 percent annually.3 The Univac I mainframe computer, first acquired by the US Census Bureau in 1951, was the size of a one-car garage, weighed 29,000 pounds, and cost$159,000—about $1.4 million in today’s terms.4 Today, anyone with $200 can buy a smartphone with a thousand times as much computing power—and can use it to tap into a worldwide computing network.5

Many other consumer and business goods have followed similar paths.

In one major sector of the economy, however, prices seem to just keep going up and up, and without a commensurate increase in performance. And that’s government.

More money for the same product

“In retail, consumers are continually getting things bigger and cheaper than before,” says Tony Dean, former Cabinet Secretary for the province of Ontario. “But for public services, we just keep asking citizens for more money for the same product. That’s no longer credible. People feel as though they’re paying enough.”6

This pattern can be observed throughout the public sector.

Higher education

If you went to a public university in the 1980s it would have cost you about $3,800 a year (adjusted for inflation). Today, thanks to college costs increasing at twice the rate of inflation, you would have to shell out close to $12,800, on average. The state-of-the-art lab equipment, research facilities, and stadiums the price increases have purchased may increase a university’s reputation, but they’ve also made it harder and harder for families to afford higher education.7 The average debt load for the class of 2008 was $23,200, compared to just $12,750 (inflation-adjusted) for the class of 1996.8

K-12 education

K-12 education cost increases are a bit lower than higher education—they’ve merely doubled in the last 30 years in the United States.9 We see similar patterns in other OECD countries, where expenditure per student on primary and secondary schools increased on average by 40 percent between 1995 and 2006.10

Security and defense

Security and defense also cost more and more each year. US intelligence costs, for example, have more than doubled since 9/11.11

Health care

The steep and steady increase in government health care costs has exceeded nearly all the other categories. US spending on Medicaid and Medicare has outstripped inflation for decades.12 At its current rate of growth, government spending on health care in the United States will soon overtake private spending.13 Other countries are seeing similar growth. Health care spending skyrocketed by 7.4 percent annually in Canada from 1999 through 2009, far surpassing the growth in GDP and inflation.14 Health care now consumes nearly 40 percent of some Canadian provincial budgets.

To be sure, performance has improved in many of these areas, but not nearly as fast as spending has gone up. What’s more, costs have risen faster than our ability to pay. The money just isn’t there to support the kind of rapid and sustained cost increases we’ve seen in the past decade or two across these sectors.

So why does the public sector seem so immune to the kind of innovation that allows us to get more for less over time? The lack of competition and profit motive in the public sector certainly plays an important role. As do the political incentives to increase spending and protect incumbents over upstart providers. But something else is at work, because industries outside the public sector also have seen little of the radical “more for less” innovation we see often in technology and other fields.15

A solution in disruption?

The ultimate reason for this difference may be the presence or absence of a phenomenon called disruptive innovation. First articulated by Harvard business professor Clayton Christensen,16 disruptive innovation “describes a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves ‘up market,’ eventually displacing established competitors.”17

Disruptive innovations start out less good but cheaper than the market leaders, but then break the trade-off between price and performance by getting better, and typically even cheaper, over time. Disruptive innovation puts the lie to the traditional notion that you always have to pay more to get more.

In sectors of the economy where disruptive innovation is commonplace, consumers are accustomed to steady price reductions and performance improvements over time—think of computing, electronics, steel manufacturing, and telecommunications.

In sectors with little or no disruptive innovation, by contrast, costs and prices generally rise over time. Government is particularly conspicuous in this respect. Studies demonstrate low or even declining productivity in many government sectors. The UK Office of National Statistics found that total public service productivity actually fell by 0.3 percent between 1997 and 2008.18 Compare this with private sector productivity, which rose by 2.3 percent annually during the same period.19

By breaking seemingly immutable trade-offs, disruptive innovation offers a potentially powerful tool to policymakers to get more for less: a way to reduce costs by upwards of 50–75 percent in some instances while maintaining or improving services.20

In this paper, we advance a contrarian argument: that disruptive innovation can not only occur in the public sector, but that it can in fact thrive. Such an argument flies in the face of the conventional wisdom that the public sector is the last place where you find really transformative innovation. While that may generally have been true in the past, it needn’t be so now.

Creating the conditions for disruption will first require policymakers to view government through a different lens. Instead of seeing only endless programs and bureaucracies, the myriad responsibilities and customers of government can be seen as a series of markets that can be shaped in ways to find and cultivate very different, less expensive—and ultimately more effective—ways of supplying public services.

Before considering how to apply disruption to the public sector, let’s begin by going a bit deeper into the concept itself.

In sectors of the economy where disruptive innovation is commonplace, consumers are accustomed to steady price reductions and performance improvements over time.

Disruptive innovation A primer

The notion that the public sector can’t—or won’t—innovate is a myth. Innovation in government occurs virtually every day—from the way governments across the world are opening up their data to entrepreneurs to build apps for everything from real-time transit information to school test score comparisons to the myriad ways soldiers on the battlefield innovate to address life-and-death challenges.

Despite these examples, however, government innovation is rarely if ever disruptive. Instead, it typically represents what is called sustaining innovation. Sustaining innovation can improve existing products or services, typically adding performance but at a higher cost—and, typically, greater complexity. Some sustaining innovations are incremental, year-to-year improvements. Others are dramatic, such as the new breakthrough business models that emerged from the transition from analog to digital telecommunications, and from digital to optical.21

Because technology allows organizations to add incremental improvements quickly, products and services often overshoot the market, becoming too “good”—too expensive and too inconvenient for many customers.

Consider the laptop. New features have improved its speed, capacity, and capability, but the concept of the laptop itself hasn’t changed drastically in 20 years. Today, many of the most advanced capabilities of laptops are irrelevant to most of their owners—they can do more than most consumers require. Most laptop users spend a third of their online time simply checking email or browsing the Web; they don’t necessarily need a terabyte of data or high-resolution graphic processors.22

Sustaining innovations have numerous strengths, typically driving up quality and performance. They are a necessary element of nearly any organization’s innovation approach, but they do have one major shortcoming: They tend to result in price inflation of 6 to 12 percent a year.23 This means that even where the public sector is innovating—unless the innovation is of the disruptive variety—costs typically will rise faster than the rate of inflation. What this means is that the most common type of innovation often actually drives costs up, not down.

How can this be true? Because incumbent producers tend to innovate faster than customers’ lives change.24 To attract the top-tier consumers who are willing to pay extra, producers layer increasingly complex and expensive features onto existing innovations, overshooting the performance for which mainstream customers are willing to pay.25

In the public sector context, the quest for higher and higher performance levels often results in increasingly complicated and expensive approaches—more for more. Think of airport security. Screening techniques have improved dramatically since 9/11 but at a substantial cost, both in price and complexity. Many of the screening technologies were designed to detect a specific threat item—for example, the bottled liquid scanner. The current checkpoint system comprises multiple screenings that are cumbersome, lengthy, and expensive. A system that could screen passengers less intrusively, more quickly, and more cheaply through segmentation or other approaches might be quite attractive for both the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and the traveling public. The TSA’s Risk-Based Security initiative, announced in 2001, could potentially do just that: do more without costing more.

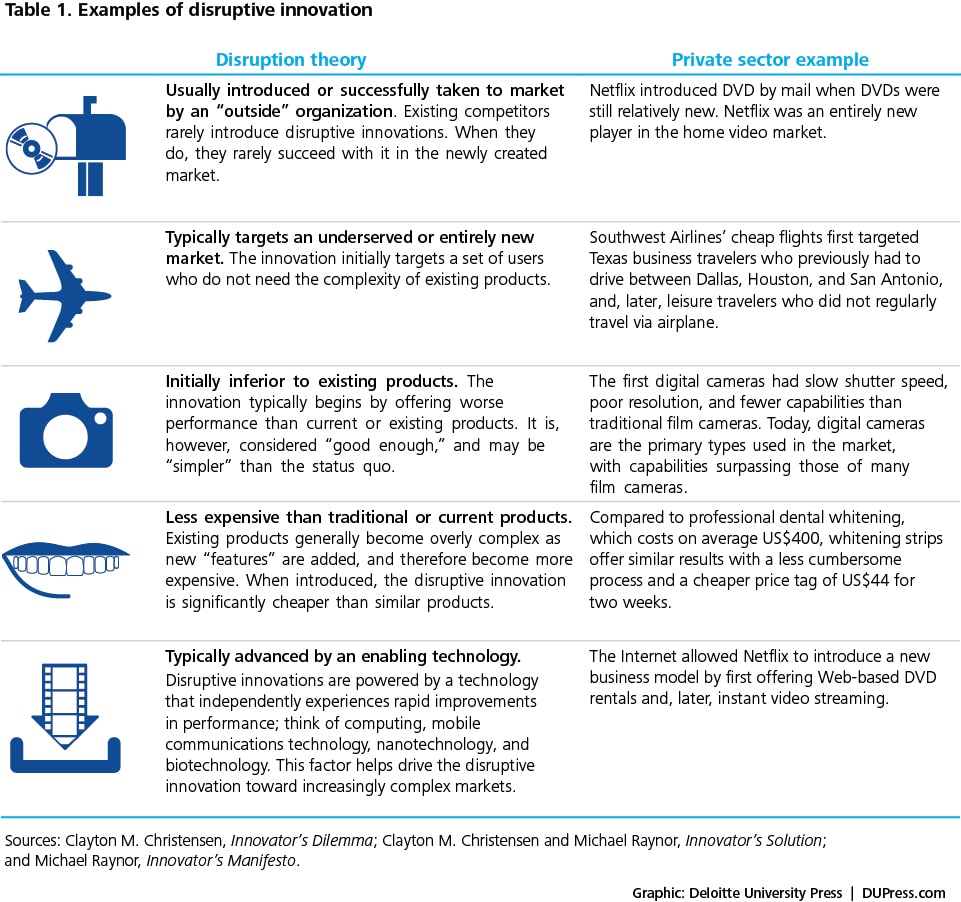

Table 1. Examples of disruptive innovation

Examples of disruptive innovation

Examples of disruptive innovation

Disruptive innovation comes from a very different mold. These innovations can provide a whole new population of “underserved” consumers access to a product or service that was previously available only to a few. In Africa, for example, mobile banking services like mPesa provide cheap and simple branchless banking for a population that had been massively underserved by banking institutions. Hundreds of examples of disruptive innovation have been catalogued in recent decades, ranging from personal computers to mini steel mills. The companies responsible for disruptive innovations often grow to dominate the industries they enter.

Health clinics

Disruptive innovations are springing up throughout the health care industry. One example is the MinuteClinic, which offers quick and convenient health care delivered by nurse practitioners at kiosks in retail stores. The idea behind MinuteClinic is to integrate simple, high-quality health care solutions into consumers’ lifestyles. MinuteClinic visits are 30 to 50 percent cheaper than an office visit at a primary care clinic, and users report a satisfaction rate of more than 97 percent.26

As a new entrant, retail clinics represent a threat to many traditional health care industry stakeholders. To consumers, health plans, and employers, they offer an important care alternative, with “good enough” health care now available at 518 clinics in 25 states.27 As higher-volume, lower-complexity transactions move to MinuteClinic models, they will also help reveal the real costs of the more complicated and expensive low-volume health care cases because they will end the cross subsidy that exists today.28

iPads

The iPad may represent another disruptive innovation. With its simple design and intuitive user interface, the iPad provides a “good enough” alternative to more expensive laptops for customers who don’t require many of the features laptops offer. While the first-generation iPad lacked features such as a webcam and a USB port, it was “good enough” for email; playing videos/music/podcasts; viewing photos, books, and .pdf documents; playing games; surfing the Web; and social networking.

In the first decade of the 21st century, only a few hundred thousand tablet devices were sold.29 Apple, by contrast, sold 14.8 million iPads in its first year.30

Cell phones

In the early days of mobile devices, “good enough” meant a large device, dropped calls, poor audio, short battery life, and high cost. These bulky cell phones did, however, offer the disruptive advantage of mobility. With improved technology over time, these performance trade-offs began to vanish. As the cost/performance curve changed, so did adoption, with cell phones eventually replacing many landlines and overtaking computers as the device of choice for most consumers. By 2010, there were more than 5 billion mobile phones worldwide, five times the number of PCs.31

Disruptive innovations have revolutionized many industries. They’ve affected how we entertain ourselves, how we communicate with one another, how we shop, and how we travel. With budgets tightening and little appetite for new taxes, what can the public sector learn from decades of disruptive innovations? A start would be to take note of Apple’s late ’90s ad campaign … it’s time for the policymakers to think differently.

Where the public sector is innovating—unless the innovation is of the disruptive variety—costs typically will rise faster than the rate of inflation.

The public sector economy A new way to think about the public sector

You have to look pretty hard to find examples of disruptive innovation in the public sector. One’s first inclination may be to blame this on structural issues unique to government. And to be sure, profit motives, competitive pressures, and other factors that propel disruptive innovation in the private sector are muted or absent in the public sector. Moreover, government rules and regulations often prevent the “less good,” potentially disruptive option from even entering the market for public services.

Even so, the lack of disruptive innovation in government is not inevitable. Government actually has certain built-in advantages it can use to overcome some of its distinct structural obstacles, and encourage and shape disruptive innovation. Let’s consider some important points:

Governments can shape the markets in which they operate

Until recently, residents in some rural areas couldn’t access many retail goods now taken for granted. When they were available, their prices were much higher than in cities and suburbs. Walmart brought low prices and every manner of consumer goods to rural America. It also brought unprecedented buying power to the retail market, meaning that the company could deliberately shape the entry of products into new markets, and thus help drive down prices.

Similarly, government’s enormous buying power has the potential to shape and create markets in ways that can deliberately foster disruptive innovation. At $500 billion annually, the US government, for example, is the world’s largest purchaser of goods and services. In dozens of economic sectors, from K-12 education to defense, from transportation infrastructure to health care, government is either a dominant or the dominant buyer in the market. The public sector already plays a major role in each of these markets, whether intentionally or not. Instead of simply supporting status quo approaches whose costs typically increase over time, public agencies can use their buying power to steer markets where they are a major buyer or deliverer toward more low-cost, disruptive approaches. This often means opening up the market to new, low-cost providers.

The armed services, for example, have tremendous power to affect the types of technologies that enter the defense market—choosing, for example, to rapidly expand the number of unmanned or remotely piloted vehicles conducting air and maritime surveillance, reconnaissance, command and control, airlift, and combat missions. And the same is true for other sectors. If state legislatures, for example, believe that online learning can transform education—and do so at a lower cost—they can “grow”’ the market for this innovation by redirecting existing funding from traditional models.

In the social services arena, the UK government has used its buying power to aggressively build the capacity of social enterprises and private providers to deliver an array of social services. Dozens of innovative new models of service delivery have resulted from this focus.32

Within the markets government operates in exist multiple segments with a diversity of providers—for profit, nonprofit, public sector, social enterprises, and so on. Consider education. Traditional K-12 schools, preschool, tutoring, test preparation, remedial education, specialized language instruction, and vocational education all constitute distinct market segments. Each segment in turn has considerably different degrees of public and private sector involvement in the market.

Thinking of the public sector as a “public service economy”33 with multiple market segments and, potentially, thousands of providers is a useful starting point in seeing opportunities for disruptive innovation.

Each government market involves trade-offs that drive up costs or reduce performance

Within each of the market segments of the public service economy exist certain “trade-offs” or “constraints.” A trade-off defines the limits of what is possible at any given time. It forces you to choose between, for instance, a product that is very simple to use and one that might have far superior performance possibilities but is more complicated.34

The most common trade-off in the public sector is between the “price” we pay for a public sector good and its performance. In education, for instance, it is generally assumed that better performance requires more teachers, smaller class sizes, and better facilities. Under the traditional model of schooling, reducing the number of teachers and increasing class size—as is happening across cash-strapped America today—is typically seen as harming performance.

The same perceived price-performance trade-off plays out across the public sector. Better intelligence capabilities require governments to spend large sums on expensive technologies such as satellites. Safer streets require more prisons. Greater national security means more bombers and more boots on the ground. Reduced traffic congestion requires more roads, bridges, and tunnels. Better performance and capabilities inevitably seem to involve paying more.

Trade-offs to be broken

- Price or performance

- Access or performance/cost

- Speed or quality

- Level of effort or result

- Customer delight or customer convenience

Other trade-offs exist as well. A common one in government is the trade-off between convenience and quality. The IT systems that support many government programs are extremely sophisticated—sometimes so complex that only a tiny percentage of public employees ever learn how to use them effectively. The child welfare systems that support social workers in many states and counties, for instance, are big investments aimed at tracking cases. But in many cases, these systems cannot talk to each other and are extremely difficult for case workers to use.

Government stimulus spending exemplifies another traditional trade-off: that between speed and quality. The pressure to move quickly vastly increases the likelihood of fraud, waste, and abuse. Cost overruns, time overruns, cancelled projects, poor project selection, bid rigging, false claims, corruption, and kickbacks are just a few of the consequences of trying to move too fast to spend public money.35 To try to break this trade-off, the Obama administration built in an unprecedented degree of public transparency into how the 2009 stimulus funds were spent. Much of the watchdog role of identifying fraud was outsourced to citizens themselves, who were encouraged to report suspected fraud, waste, or abuse on a user-friendly website.

Access versus performance is another common trade-off. From schools to policing to libraries, wealthy communities typically can afford to provide more and better public services than poorer communities. They often pay their teachers higher salaries, have more police officers, and offer residents better amenities. Breaking this trade-off might entail finding a way for children in poorer communities to have access to top-quality schools, health care, and athletic facilities without dramatically raising costs.

“Trade-offs define the limits of what is possible at a point in time, not what is possible for all time. We learn. We improve. We innovate. In other words, we figure out how to get more for less.” Michael Raynor, author, The Innovator’s Manifesto

Disruptive innovation eliminates critical trade-offs

Ten years ago, if you wanted to see a 1950s art house classic, you could drive to the nearest video store, search the movie stacks, hope they carried the movie, and that it wasn’t checked out—not a terribly convenient process. Yet it did allow you to watch the movie you wanted to see, when you wanted to see it—if you were lucky. The trade-off was between convenience (watching something that happened to be on cable that night) and satisfaction (watching exactly the movie you wanted that night).

Netflix shattered this trade-off. Its video streaming service allows us to order up any of tens of thousands of movies and television shows, and watch them in the comfort of our home within seconds.

Catalysts for disruptive innovation

- Not a sustaining technology

- Produced by an autonomous organization

- Less expensive than traditional technology

- Maintains cost-competiveness over time

- Enabled by a rapidly evolving technology

- Demonstrated effectiveness in real-world use

- Avenues created for low-risk innovation

Or consider automobiles. For many city dwellers, owning a car is a major hassle. They may use their cars only occasionally, yet still have to fight for parking spaces or shell out a fortune for garage parking on top of a $400 monthly car payment. As costly and inconvenient as this is, it generally still beats finding a rental car agency, waiting in line, and paying $50 a day each time you want a car to go shopping.

In many cities, however, this frustrating trade-off no longer exists. Car-sharing services such as Zipcar allow urban dwellers to pick up a car within blocks of their homes for less than $10 an hour. Best of all, you can pick up a sports car for that special date one night and use a pickup truck the next day to transport your new sofa.

Car-sharing services break multiple trade-offs—price versus performance and access versus performance. People who may not be able to afford car ownership can have regular access to cars at a fraction of the price of ownership, and without all the hassles. By breaking these trade-offs, Zipcar and 200 other similar car-sharing services may disrupt both the car rental and car ownership markets.

What about government? How can disruptive innovation help government to break trade-offs and reduce costs? What are the best opportunities to do so? The next section provides five examples of how disruptive innovation can significantly lower costs in the public sector by breaking similar trade-offs.

Opportunities for disruptive innovation Five cases in the public sector

Transforming criminal justice with electronic monitoring

For decades, politicians have offered voters a stark choice: less crime and greater safety means tougher sentencing laws and a great deal more money spent on incarceration. Fewer prisoners, in turn, were seen as equaling higher levels of crime.

This perspective has dominated criminal-justice thinking in much of the world, and nowhere more so than in the United States, which houses a higher percentage of its population behind bars than any other country. With less than 5 percent of the world’s population, America has nearly one-quarter of the world’s prisoners.37

As of 2008, approximately 2.3 million people were behind bars in the United States, equivalent to about one in every 100 adults. This represents a 300 percent increase in the prison population from 1980, when half a million Americans were behind bars.38 Lower-level offenders, moreover, have accounted for a significant portion of this growth.

Figure 1. Number of offenders that can be tracked for the cost of one prison bed

This rise in incarceration came at a huge monetary cost. US state corrections costs now top $50 billion annually and consume one in every 15 discretionary state budget dollars.39 Prison costs now trump higher education costs in some states.40 California, for instance, spends 10 percent of its general revenue on prisons and only 7 percent on its higher education system of 33 campuses and 670,000 students.41 And the social cost for many minority communities, where a large percentage of the young men are now locked up, is staggering.42

This rise in incarceration came at a huge monetary cost. US state corrections costs now top $50 billion annually and consume one in every 15 discretionary state budget dollars.39 Prison costs now trump higher education costs in some states.40 California, for instance, spends 10 percent of its general revenue on prisons and only 7 percent on its higher education system of 33 campuses and 670,000 students.41 And the social cost for many minority communities, where a large percentage of the young men are now locked up, is staggering.42

Though the United States tops the charts in prison population, many other countries, from Brazil to Russia, also incur huge budgetary and societal costs from extremely high incarceration rates.

Breaking the trade-off

The technology with the greatest potential to break this trade-off and disrupt traditional incarceration originated as a way to monitor the eating habits of cows. For years farmers have used radio frequency-identification (RFID) tags to keep track of their cattle.

Today, the technologies involved in electronic monitoring include home monitoring devices controlled by radio, wrist bands and anklets tracked by global positioning systems (GPS), alcohol testing patches, and even voice recognition.

The criminal justice system uses electronic monitoring (EM) technologies primarily for offender tracking, confirming that offenders are where they are supposed to be or are prevented from approaching identified high-risk areas. For example, authorities can be alerted when a sexual offender approaches a school or playground.

Criminal justice by the numbers

- US corrections costs= $50 billion annually

- Consumes 1 of every 15 discretionary state budget dollars

- California spends more on prisons than higher education

EM technologies generally fit into one of two categories, passive or active. Passive monitoring involves programmed contact, whereby a computer calls an offender at random or at specific times of day. The technologies are passive in that the offender’s presence is only noted when contact is made. Active monitoring systems are more common, and are called active because a continuous signal exists between the offender and monitoring authorities. Typically, some sort of transmitter attached to the offender (an anklet or bracelet) continuously transmits their whereabouts via GPS or RFID tags.43

Cost savings from electronic monitoring

- Daily costs of prison in the US=$78.95

- Daily cost of electronic monitoring=$5–$25

- Savings from moving 50 percent of low-level offenders from prison to EM=$16.1 billion

By removing low-level offenders from jails and prisons and putting them under house arrest, local, state, and federal governments could dramatically reduce their spending on incarceration.44 It replaces a one-size-fits-all approach for offenders with one that better segments the population and employs the most appropriate and cost-effective approach for each offender segment depending on the crime committed and potential danger to the community.

In 2008, the average daily cost of incarcerating a prison inmate in the United States was $78.95.45 By contrast, the average daily cost of managing offenders through electronic monitoring technologies ranges between $5 and $25 per day, depending on the type of technology used and the community using the technology.46 Many localities, moreover, bill offenders for the cost of electronic monitoring and equipment.47

Non-violent offenders today make up more than 60 percent of the US prison and jail population.48 Figure 2 shows the potential savings from shifting varying percentages of these non-violent offenders from incarceration to electronic monitoring. The approximate annual savings from moving 50 percent of low-level offenders to electronic monitoring would be about $16.1 billion.49

Figure 2. Potential net savings per day from electronic monitoring

In addition to direct savings, EM also creates significant savings in opportunity costs. The Pew Charitable Trusts estimates that “two-thirds of male inmates were employed and more than half were the primary source of financial support for their children” before beginning to serve their sentences.50 Placing these offenders behind bars, at an enormous cost to government, also removes them from their jobs. They are no longer providing tax revenue to their communities and can no longer provide for their families, increasing the demand for government resources.

In addition to direct savings, EM also creates significant savings in opportunity costs. The Pew Charitable Trusts estimates that “two-thirds of male inmates were employed and more than half were the primary source of financial support for their children” before beginning to serve their sentences.50 Placing these offenders behind bars, at an enormous cost to government, also removes them from their jobs. They are no longer providing tax revenue to their communities and can no longer provide for their families, increasing the demand for government resources.

Pace of disruption

In the United Kingdom, about 70,000 offenders are subject to electronic monitoring annually, a number likely to rise significantly in the near future.51 In October 2011 alone, the UK government bid out £1billion worth of electronic monitoring contracts. Significant growth in electronic monitoring is also expected in other European countries as well as Brazil and South Africa.52

Figure 3. Expanding capabilities of electronic monitoring (EM)

Will EM disrupt how we think about incarceration for non-violent offenders? Only time will tell, but as governments are forced to seek cost reductions and innovative ways to use existing resources, EM is already climbing the productivity curve (see figure 3).

Will EM disrupt how we think about incarceration for non-violent offenders? Only time will tell, but as governments are forced to seek cost reductions and innovative ways to use existing resources, EM is already climbing the productivity curve (see figure 3).

Already, new devices such as alcohol detection patches are augmenting EM by monitoring and thus discouraging specific behaviors, such as consuming alcohol or drugs. These technologies force the criminal “to monitor himself … effectively outsourcing the role of prison guard to prisoners themselves.”53

Several governments have made concerted efforts to spur the more rapid adoption of electronic monitoring. The United States is believed to be the biggest subscriber to electronic monitoring. More than 20 different electronic monitoring companies provide electronic monitoring for more than 100,000 offenders, according to best estimates.”54 Other countries are moving rapidly in this direction.

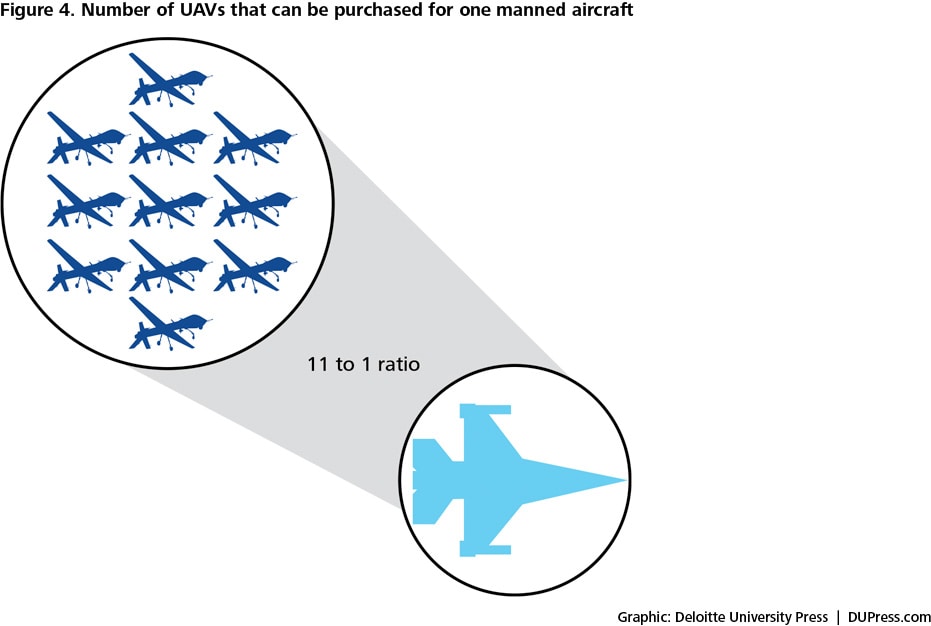

Figure 4. Number of UAVs that can be purchased for one manned aircraft

Defense: Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)

Defense: Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)

Warfare is enormously expensive. US military superiority results from a number of factors, but one of them surely is having the most sophisticated weaponry—and a lot more of it than anyone else. But the latest, greatest fighter jets, ships, and submarines don’t come cheap. Between fiscal year 2000 and 2011, the US Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) base budget increased by 91 percent.

In recent years, however, at least one disruptive technology has gotten considerable traction in warfare. Once a feature of science fiction, the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) has become “the poster child for transformation” of the military55—and what may turn out to be one of the most important new military weapons of our time.

Today, the US military, intelligence, and border security sectors employ UAVs for an astoundingly diverse range of activities, including real-time surveillance, critical combat search-and-rescue missions, and assistance in the apprehension of terror suspects. Moreover, UAVs are now being used to execute operations typically reserved for manned attack aircraft, such as missile strikes on high-value targets.56

In all, it’s estimated the United States has more than 7,000 UAVs in operation.57 Others are racing to catch up—more than 50 countries have built or bought unmanned aerial vehicles, according to defense experts.58 Recent estimates indicate that the UAV industry, supporting a broad and evolving range of military, intelligence, and commercial sector activities, will become a $50 to $94 billion annual business within the next 10 years.59

Thanks to their persistence, cost, and flexibility, UAVs are clearly disrupting existing defense and intelligence operations.60 The Pentagon’s recommendation to curtail the development of the manned F-22 and F-35 aircraft while increasing its procurement of UAVs is just one sign of this development.61 Additionally, in the future, the Navy plans to dramatically expand the number of remotely piloted vehicles to perform underwater missions such as finding mines, detecting enemy ships, and providing port and harbor security—missions now routinely conducted by more expensive manned vehicles.

Breaking the trade-off

One of the best-known UAVs is General Atomics Aeronautical System’s (GA-ASI’s) Predator drone. As with other disruptive innovations, the Predator has consistently broken existing cost and performance trade-offs in the defense and intelligence arenas. At roughly $4.5 million, the Predator costs just a fraction of the tab for manned aircrafts and satellites; it even undercuts other UAVs in cost-competiveness.62, 63

As for performance, Predators and other UAVs actually provide several key performance capabilities that exceed those of manned aircraft: persistence (the ability to provide persistent coverage over an area for an extended period of time); flight longevity (days compared to hours for manned aircraft); undetected penetration; the ability to operate in dangerous environments; and the ability to conduct remote operations with fewer direct combat personnel.64 And of course, they do not require a pilot to go into harm’s way.

Pentagon officials say the remotely piloted planes, which can beam back live video, have done more than any other weapons system to track down insurgents and save American lives in Iraq and Afghanistan.65 “[The] remotely piloted aircraft was one of the most important developments since 9/11,” says Air Force Chief Scientist Dr. Mark Maybury.66

In 2011, the US Air Force will train more “joystick pilots” than new fighter and bomber pilots.67

How did this come about?

The viability of the UAV as a modern surveillance and reconnaissance platform was first realized during the 1980s, when Israel demonstrated the advanced capabilities of its low-cost Scout UAV over Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. The Scout was capable of real-time surveillance and was difficult to detect and destroy, as it was made of lightweight fiberglass with a low radar signature.

The big break for UAVs, however, came in the mid-1990s, when the Advanced Concept Technology Demonstration program (ACTD), a small procurement shop at the Pentagon responsible for funding and testing innovative technologies, decided to invest in them. The Predator effort began with a 30-month ACTD contract awarded in January 1994.

The Predator’s mission is to provide long-range (500 nautical miles), long-endurance (up to 40 hours), and near real-time imagery for reconnaissance, surveillance, and target acquisition. These capabilities were demonstrated in Bosnia. The performance data gathered there “convinced the military users that the Predator was worth acquiring.”68

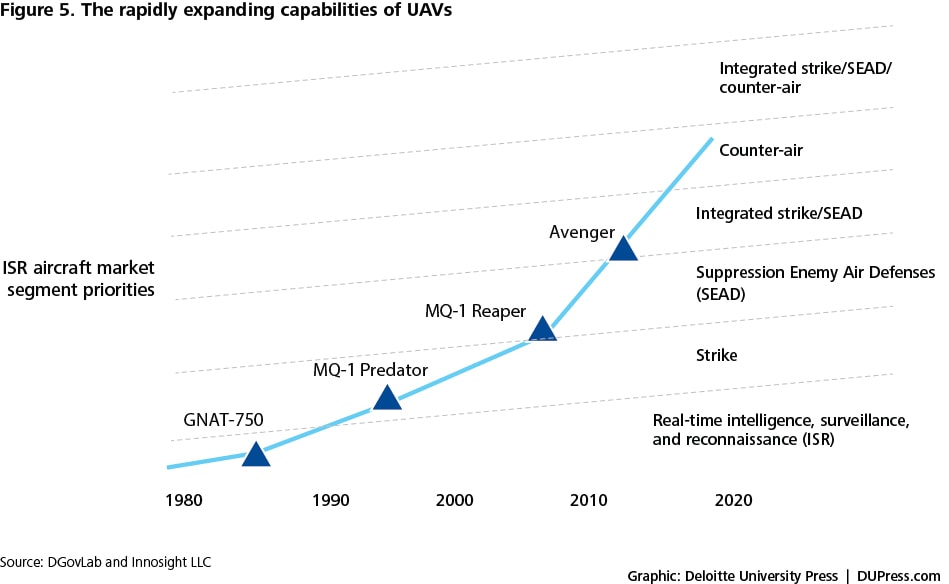

Figure 5. The rapidly expanding capabilities of UAVs

Pace of disruption

Pace of disruption

Once integrated into defense and intelligence operations, the UAV adapted quickly to evolving performance needs. Recalls General Atomics CEO Tom Cassidy Jr.: “The airplanes, the way we designed them, was for a lot of growth, to be capable of carrying weapons and to control them through satellites. We figured that was kind of the way of the future …”69 From miniaturization to real-time digital imagery, the Predator and other UAVs such as the Global Hawk, Reaper, Sky Warrior, and Avenger have continuously advanced to meet the dynamic challenges of post-9/11 military warfare.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 created new demand for weapons systems that could conduct reliable, real-time surveillance and reconnaissance as well as satisfy combat needs. In response to these changing needs, General Atomics equipped Predator drones with Hellfire missiles. The Air Force put the weaponized Predator into immediate use in Operation Enduring Freedom, hitting approximately 115 targets in Afghanistan during its first year of combat operations. According to one report, “Iraqi soldiers actually surrendered to a Pioneer, knowing that after it spied them, gunfire was imminent.”70

The UAV experience demonstrates that revolutionary technologies can disrupt even the most seemingly hidebound operations. UAV proponents in and outside of government began by identifying a need for low-cost, basic unmanned aircraft. Once the initial technology was proven, the UAV manufacturers continually and relentlessly improved the capabilities. As a result, UAVs have transformed the way the US government conducts intelligence and military operations. Even the successful operation to uncover and kill Osama Bin Laden relied on intelligence gathered by a stealth UAV.71

The flexibility, versatility, and low costs of UAVs have resulted in their extension into an amazingly diverse set of tasks (see accompanying box).

A sampling of the diverse uses of UAVs

Military and intelligence

- Reconnaissance

- Surveillance

- Strike

- Close combat support

- Deception operations

Security

- Policing

- Border patrol

- Perimeter security (close quarters, inside buildings, over hills)

- Port monitoring/security

Environmental, emergency response, and infrastructure

- Surveillance (intelligence, oil rigs, and pipelines)

- Storm and weather monitoring

- Search and rescue

- Emergency management (wild-fire monitoring, suppression, and fire-crew information tool)

- Damage assessment (natural disasters, battle environments)

- Monitoring real estate

Five lessons learned from UAV adoption

The convergence of multiple internal and external factors helped UAVs emerge as a disruptive innovation in the defense space.

1. Organizational autonomy

UAVs were introduced as an alternative technology to manned aircraft by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems Inc., a company outside the ranks of traditional military aircraft contractors. The company invested tens of millions of dollars of its own money into UAV technology in the belief that UAVs would prove transformational. “Everyone talks about how the world has changed,” explained CEO Tom Cassidy in justifying the investment. “We’re building the technology for where it’s going.”72

2. Start off worse but rapidly evolve the technology

Although the initial UAVs lacked dual surveillance and combat capabilities, they were significantly less expensive than traditional aircraft—and safer for personnel, obviously.73 UAV capabilities rapidly evolved to satisfy the changing needs of post-9/11 warfare.74

3. Highly adaptable platform

The rapid evolution of UAVs was made possible by highly nimble platforms that proved extremely conducive to customization and improvement, which includes everything from video cameras to missiles.

4. May require significant trial and error

Prior to the Predator UAV, the US Department of Defense (DoD) experienced repeated failure launching a UAV program. Between 1975 and 1996, the DoD spent about $4 billion on nine UAV programs that were all canceled without producing significant real-world benefits to national military or intelligence activities.75 Importantly, however, the DoD, the intelligence community, and defense manufacturers didn’t give up.76

5. Proof of concept

UAVs gained momentum once they were proven in combat. A pivotal point in their acceptance was the effectiveness of the Predator during the beginning of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

At least two-thirds of US students will be doing most of their learning online by 2020.—Tom Vander Ark, CEO of Open Education Solutions

K-12 education

Today’s students have more choices in classes, better facilities, and a wider variety of learning experiences than ever before. But the fundamental way in which most children are taught has not changed significantly in more than a century. And while education has become considerably more expensive, it has failed to achieve a corresponding increase in performance.

Breaking the trade-off

The trade-off schools have faced is between the kind of standardized teaching that occurs in most public-school classrooms and the more personalized instruction a student might receive from a tutor or at an elite prep school. Smaller class sizes, smaller schools, “schools within schools,” and other reforms all reflect attempts to move up the performance curve. The trade-off, however, is that such reforms typically are quite expensive.

Online learning, or a blended learning environment of digital learning and traditional instruction, may be capable of breaking this trade-off. How? By personalizing the learning experience according to individual student learning styles and pace, and doing so without increasing the number of teachers. Within five years, most learning platforms will have a smart recommendation engine similar to iTunes Genius that can create customized learning experiences, predicts Tom Vander Ark, CEO of Open Education Solutions.77 These new, customized learning systems typically are based in the “cloud” and accessible to students anywhere.

Pace of disruption

Thanks in part to much greater capabilities, today’s online learning courses are moving rapidly from test preparation and correspondence classes into mainstream education. More than 4 million students at the K–12 level took an online course in 2011, up significantly from just 1 million three years earlier.78 About 250,000 US students attend online schools full time, mostly through virtual charter schools.79

The Innosight Institute predicts that the pace at which online learning substitutes for live classroom instruction will increase dramatically in the next decade. In 2008, they estimated that by 2019, American high school students will take 50 percent of their courses online.80 This was a bold prediction, to say the least. If the current 46 percent annual growth rates in online learning continue, however, it may prove too conservative. Vander Ark predicts that at least two-thirds of US students will be doing most of their learning online by 2020.81 That would indeed be quite a disruption.

The Khan Academy’s disruptive model

One of the most disruptive education models started off as Salman Khan’s side project to provide tutoring help to his cousins, nephews, and nieces. The simple but effective math and science videos Khan posted to YouTube quickly went viral as thousands and then millions of students started to watch. All told, Khan’s now world-renowned online learning academy has delivered more than 30 million lessons to students around the world.82

The 2,700 online course modules offered by the Khan Academy range from math and science to art history to banking and money. Each lesson is free and open to anyone. With the help of philanthropic supporters, Khan’s tiny six-person team has steadily moved Khan Academy up the performance curve. The website now includes a sophisticated analytics engine that allows teachers and parents to track student progress through experience points gained as the students master various subjects.83 The five years’ worth of data Khan now has on how students learn could eventually enable the academy to create lessons personalized to each student’s learning.

At least 36 schools have incorporated Khan Academy videos and teacher dashboards that track students’ individual statistics into their teaching model.84 The Los Altos school district in northern California uses the Khan videos to “flip” some of their classrooms: Students watch the taped Khan lectures for homework so teachers can spend class time working one-on-one with students, helping them work through tough questions.85 Teachers in hundreds of other schools similarly use online tools to flip their classrooms and deliver more customized instruction.

Higher education by the numbers

- Tuition and fees at US public and private colleges rose by an average of

- 439 percent after allowing for inflation (from 1982 through 2007)86

- 6 to 7 percent annual price increases for three decades

- The average university spends $4 to $5 on overhead for each dollar spent on teaching, testing, and research

Transforming higher education

Few if any sectors of our economy in recent decades have experienced price and cost increases as massive as those in higher education. From 1982 through 2007, tuition and fees at US public and private colleges rose by an average of 439 percent after allowing for inflation.87 Three decades of 6 to 7 percent annual price increases have put college beyond the means of most families without resorting to huge student loans.88

Scores of books and studies have attempted to explain the factors behind this dizzying cost spiral.89 What they tend to conclude is encapsulated in a pithy phrase from Kevin Carey of the Washington, DC-based think tank Education Sector: “Everyone wants to be Harvard.”90

Every college and university wants to have the leading researchers who publish in top journals and lure federal grants, while also offering the most state-of-the-art academic, sports and leisure facilities. Today’s institutions of higher education try to do so many jobs that they’ve become extraordinarily complex organizations, with huge costs tied up in overhead and administrative costs. According to the Center for American Progress, the average university spends four to five dollars on overhead for each dollar spent on teaching, testing, and research.91

The prevailing wisdom in higher education is that it’s not possible to reduce costs and improve quality. The belief is that controlling costs would mean lower quality; reduced course selection; more teaching assistants and adjunct lecturers and fewer professors; and staff layoffs.92 But are these assumptions actually true?

A big chunk of the best-known American colleges … try to compete on exclusivity and the quality of the experience, not on price.—Anya Kamenetz, author of DIY U93

Breaking the trade-off

The key to disruptive innovation in higher education is to unbundle the different services colleges provide, and to bring a greater range of providers into the market.

As with K-12 education, online learning is the technology offering the most potential to transform higher education’s basic business model. It can be used to unbundle some of the services colleges now provide, allowing students to pay only for what they need.

Disruptive entrants such as the University of Phoenix, DeVry, Western Governors University, MIT’s OpenCourseware and MITx, the United Kingdom’s Open University, and many community colleges unbundle the cost of learning from the hefty costs of stadiums, student unions, swimming pools, fitness centers, and administration. Online learning allows their low-cost business models to scale upward and compete against traditional colleges and universities.

Can online learning achieve good results while offering significantly lower costs than traditional college instruction? The evidence suggests it can.

During the last decade, the National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT) has worked with hundreds of public universities to redesign individual courses around a blended model of education that takes greater advantage of technology.94 These course redesigns have covered all sorts of disciplines, from Spanish to computer science to psychology. They typically incorporate digital learning tools—simulation, video, social media, peer-to-peer tutoring, and software-based drills—as well as some traditional classroom lecturing.

Blended learning: Where the cost savings come from

The average cost reduction from blended learning in higher education has been 39 percent, with some course costs reduced by as much as 75 percent.95 Here are some of the ways these savings have been realized:

- Faculty: Less time presenting information, developing curriculum and grading exams. Greater peer-to-peer learning.

- Resources: Reduced course repetitions. Students access material when they need it, increasing efficiency of resource use.

- Infrastructure: More efficient use of physical space.

The average cost reduction has been a whopping 39 percent, with some course costs reduced by as much as 75 percent.96 All in all, the cost of delivering a four-year degree with only online curriculum (with instructors) is less than $13,000 compared to $28,000 and $106,000 at typical public and private institutions, respectively.97

As for the quality, from test scores to student satisfaction to graduation rates, outcomes have also improved, according to NCAT.98 At the University of New Mexico, the drop-withdrawal-failure (DWF) rate in a psychology course fell from 42 percent in the traditional format to 18 percent in the new blended model. Meanwhile, Virginia Tech’s redesigned math course resulted in test scores rising 17.4 percent and the failure rate plummeting by 39 percent.99

Pace of disruption

As with K-12 education, online higher education is increasing at a brisk pace. Open University is now the biggest university in the United Kingdom, with more than 250,000 students and 1,200 full-time academic staff.

In the United States, about 6.14 million students enrolled in at least one online course in 2010. Fully 31 percent of all college and university students now take at least one course online.100

The most powerful mechanism of cost reduction is online learning. All but the most prestigious institutions will effectively have to create a second, virtual university within the traditional university …—Clayton M. Christensen and Henry Eyring, The Innovative University

Rising costs of US intelligence

In fiscal 2010, the National Intelligence Program, run by the CIA and other agencies that report to the Director of National Intelligence, cost $53.1 billion, while the Military Intelligence Program cost an additional $27 billion.101

Intelligence: Open-source data analytics

As with defense, intelligence doesn’t come cheap. The collection and analysis of intelligence has become a particularly complex and resource-intensive task. Better intelligence capabilities historically required more people, more satellites, and lots of very expensive custom technology. Complexity increased due to new external threats and by the addition of intelligence agencies, creating barriers to information sharing and increasing technological demands.102

Civilian and military intelligence cost the US government $80 billion in 2010, more than twice what was spent in 2001.103 This price tag dwarfs the $42.6 billion spent on the Department of Homeland Security or the $48.9 billion State Department budget.104

Many intelligence capabilities were created, refashioned, or grown in the wake of 9/11.105 The massive growth caused even former Defense Secretary Robert Gates to remark: “Nine years after 9/11, it makes a lot of sense to sort of take a look at this and say, ‘Okay, we’ve built tremendous capability, but do we have more than we need?’”106

The extreme level of technological sophistication needed for advanced intelligence has resulted in a number of high-profile failures, perhaps the most well-known being the cancellation of a six-year, multi-billion-dollar effort to develop the next generation of spy satellites, the Future Imagery Architecture.107 Human intelligence or “HUMINT” also comes at a cost—the cost of human life, as it often requires placing American operatives and foreign agents in potentially deadly situations.

Breaking the trade-off

Given today’s budgetary environment, the meteoric rise in intelligence spending is over—in fact, many intelligence agencies are already planning for significant budget cuts. The question then becomes: Can these same agencies provide critical intelligence capabilities at a lower price?108 The combination of two developments suggests the answer to this question may be yes.

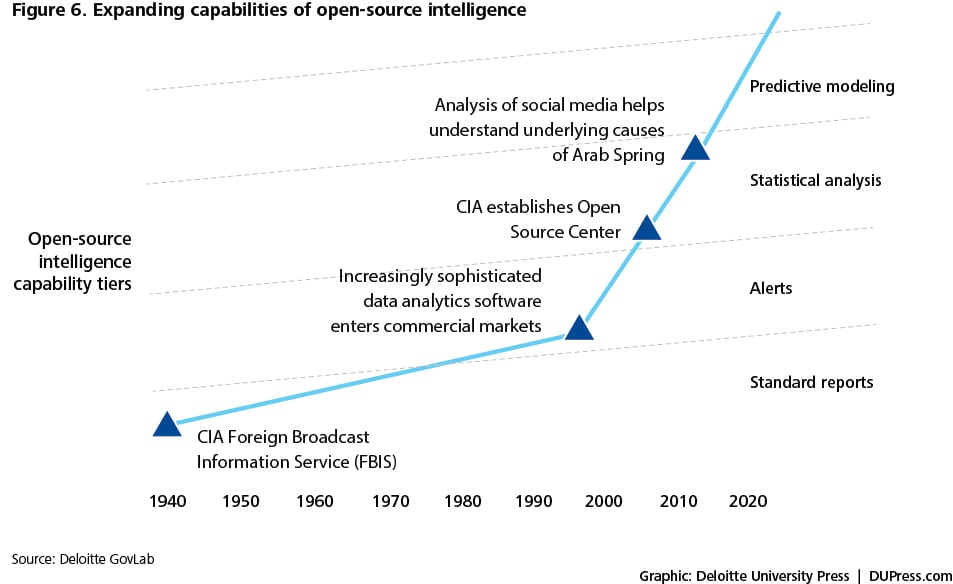

The first development is the rise in open-source intelligence (OSINT). This refers to the broad array of information and sources publicly available from the media, social networks, academia, and other public data. OSINT has been collected since 1940, but typically this collection focused on acquiring and translating mass media such as newspapers, television, and radio. The analysis of the material was done primarily by individuals and focused on understanding trends and differences in media coverage of issues. The Foreign Broadcast Information Service was responsible for this media analysis.

In 2005, the broadcasting service, previously a CIA component, became the Open Source Center. OSC was authorized by the Director of National Intelligence, but the CIA functioned as its executive agent. The OSC was charged with improving the availability of open-source material to intelligence officers and others in the government. The OSC launch signaled a more serious commitment to leveraging OSINIT, as well as the recognition that the traditional paradigm of secret intelligence operations comes with a crushingly high overhead cost.109

The value of open-source information is that it’s essentially free.110 The difficulty with open-source information is twofold. First, many intelligence professionals view open source information as ‘un-vettable,” that is, inaccurate or not actionable. Second, with the world producing the digital equivalent of the Library of Congress every five minutes—sorting out what matters from what doesn’t can seem like a Sisyphean task, the digital equivalent of finding a needle in a haystack.

A second development, advances in analytics, however, begins to address these problems. Rapidly maturing analytics technologies—modern data mining, pattern matching, data visualization, and predictive modeling tools—can help make sense of the mountains of data available today, and apply them to make more informed decisions. The speed at which these capabilities are getting better cannot be emphasized enough. Facial recognition search technology, for example, has gotten good enough to where computers can sift through millions of pictures or videos in seconds to link a picture to the identity of an individual.

These analytic technologies can help intelligence organizations to overcome data overload by pinpointing important information and filtering out extraneous data.111 Our everyday actions in the digital world, from posting messages on Facebook to checking a bank account balance, create “digital exhaust”—trails conveying information about behavior, preferences, and interactions. Analytics can help exploit this vast sea of data, thereby turning “overload” into opportunity. In the words of Clay Shirky, “There is no such thing as information overload, there’s only filter failure.”112

Open-source information matched with advanced analytics potentially enables intelligence to be provided at a lower cost.

The Arab Spring provides a useful window into the power of joining open-source information with sophisticated analytics. Simply aggregating and analyzing tweets provided one valuable window into subsequent developments. Automated analysis tools discovered that an astounding 88 percent of Arabic conversations on social media during the first quarter of 2011 included political terms, up from a mere 35 percent in 2010.113

Targeted analytics examining social-media discussions about the Egyptian crisis also revealed that conciliatory actions might have saved Hosni Mubarak’s job. Of all of the popular demands, ousting Mubarak was only the fourth most-popular, lagging behind intermediate steps such as ousting the interior minister, increasing minimum wages, and ending emergency laws.114

Social sentiment analysis capabilities make it possible to predict to the day when a certain country might have a significant public protest or the growth of a political movement. Software can also now aggregate buzz expressed across various social media outlets to predict election outcomes.115 This includes not just the ability to track the presence of a candidate’s or political party’s name and brand, but the sentiments and context of how they are discussed in social media. Algorithms can help analysts use open source to track growing distrust of specific attributes of political leaders and political parties or anticipate an uprising.

Figure 6. Expanding capabilities of open-source intelligence

Pace of disruption

Pace of disruption

Figure 6 depicts at a very high level how the upward march in capabilities in open-source methods has already impacted intelligence. IARPA (Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity) and DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) initiatives exploring how social media and sophisticated open-source methods can assist the US government to better anticipate significant societal events reflect the direction the capabilities are headed.116

Secret sources and methods will remain important for information that can only be discovered through clandestine means. Many of the new challenges facing the intelligence community, however, from detecting political instability to understanding social dynamics, might most effectively be answered through open source. As a result, open source should no longer be seen, as it is today, primarily as a source of information that supports secret intelligence.117 Open source—particularly the marriage between large volumes of data and advanced analytic techniques—could eventually emerge as the intelligence resource of choice for many priority issues.

We live in an open world, yet the intelligence community today still operates largely as a closed-loop system.118 Open-source approaches provide one way to change this paradigm.

Cost Savings from Disruptive Health Care Innovations

| Approach | Cost savings potential |

| Virtual patient visits | 25% |

| Cataract surgery costs | 5% to 7% decline per year for decades |

| Retail health clinics | 30% to 40% |

Additional opportunity areas for disruptive innovation

Health care

The enabling disruptive technologies and business models that can help drive down health care costs are fairly well understood.119 Retail clinics, telemedicine, single organ hospitals, surgical robots, medical tourism, and personalized medicine are just a few of the disruptive health care models that hold tremendous promise for breaking traditional price and performance trade-offs in this sector.120 Virtual patient visits, for example, can cut costs by one-fourth. Cataract surgery costs, meanwhile, have fallen 5 to 7 percent per year for decades due to technology, process innovation, and the establishment of specialized clinics.121 Meanwhile, patient visits to retail health clinics, where care is 30 to 40 percent less than a physician’s office and 80 percent less than an emergency room, grew 10-fold between 2009 and 2011.122

Development aid

Most developing countries are vastly underserved by banking institutions. But traditional international development organizations for their part are not institutionally well equipped to deliver low-cost disruptive innovations. The hugely successful Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, which offers women tiny loans to establish microbusinesses and buy raw materials for self-employment, provided the first alternative model to traditional development.

Today, numerous organizations have taken Grameen’s model to the next level and created technology platforms to enable anyone with Internet access and a small amount of capital to fund microfinance ventures thousands of miles away. The first online microlending platform to target the huge and underserved market of more than 2 billion people who lack access to formal or semi-formal financial services was San Francisco-based Kiva. In just a few years, Kiva has connected interested contributors to the regional networks of microfinance institutions (MFIs) in nearly 60 countries by utilizing advancements in technology to reach individuals in remote areas frequently enough to collect repayments and interest. The success of Kiva’s business model is changing how governments and NGOs alike think about foreign aid.

Emergency response

Another small organization trying to disrupt more established international aid practices is Ushahidi, which provides an open-source, free service that can overlay maps of affected regions with data gathered from a wide variety of sources, including social networking sites, email, news sites, blogs, and mobile text messages. Any piece of relevant information sent by individuals from their mobile phones or Internet connections in a disaster-stricken area can be monitored. Detailed maps can show, for instance, where people are trapped and where safe drinking water may be available.

Ushahidi’s major innovation is to use the beneficiaries of disaster relief—the victims—as contributors to the relief effort platform. While established humanitarian organizations initially viewed Ushahidi and its “unofficial” information with skepticism, they now specifically request the use of the platform and volunteer mappers in current disaster and conflict areas.

While established humanitarian organizations initially viewed Ushahidi and its “unofficial” information with skepticism, they now specifically request the use of the platform and volunteer mappers in current disaster and conflict areas.

Fostering disruptive innovation A framework for the public sector

To summarize, we’ve now introduced you to the concept of disruptive innovation, described how conceiving of the public sector as a series of markets makes it possible to see how disruptive innovation might help achieve lower costs, and applied disruptive innovation to five major public services to show the concept’s potential in government. Now we can provide a framework for introducing disruptive innovation more broadly in the public sector. This framework, which draws from Michael Raynor’s decade-long research into disruptive innovation, has three principal components:

- Focus: Identify what needs to be accomplished in the short and long term

- Shape: Decide how and where to start disrupting

- Grow: Protect and nurture the disruptive innovation

Focus: What do you want to accomplish?

When Netflix pioneered an easier way for consumers to enjoy home entertainment without late fees, its strategy focused on a new way to access movies. When Southwest Airlines first introduced low-cost airfare in intrastate Texas, they were looking to serve an entirely new consumer. The public sector must learn to think in the same way. This entails developing new models for solving individual and societal problems.

The first step is to identify the best opportunity or opportunities for disruptive innovation. In some cases, as in education and higher education, this exercise is relatively easy thanks to years of previous analysis. In many cases, however, identifying disruptive opportunities will require a strategic analysis that answers the following questions:

- What is the job that needs to be done?

- What are the current trade-offs?

- How can these trade-offs be broken?

What is the job that needs to be done?

How do you do it today? Will that change over time?

Thinking about a service or program solely in terms of the current process greatly limits developing a vision for how it might be changed or improved. The way it’s done today often prevents policymakers from seeing what might be.

A more effective approach is to ask, “What is the job that needs to get done?”123 For instance, thinking about how to improve today’s schools can lead you to limit your thoughts to the confines of a brick-and-mortar classroom. Instead, the question one might ask is, “How can we better educate children to prepare them for the workplace of tomorrow?” The latter question opens up a range of possibilities that may not even include schooling as it is traditionally understood.

Focus stage of disruption

- What is the job to be done?

- Identify the trade-offs

- Break the trade-off (via enabling technology and a disruptive hypothesis)

Focusing on the job to be done can illuminate how to accomplish the core goals of an existing process in a different way.

What are the current trade-offs?

As we have seen, Southwest Airlines provides a good example of the identification of trade-offs. To achieve its goal of offering low-cost air travel, Southwest simplified its business model by reducing food offerings and acquiring only a single aircraft type. Southwest understood that consumers were more than willing to sacrifice some amenities for cheaper fares.

Another example is the criminal justice system. Today, offenders are placed in expensive, overcrowded prisons throughout the country. Breaking the trade-off between the price we pay for punishing offenders and the performance of the punishment regime could involve shifting low-level offenders into significantly less expensive electronic monitoring programs.

In the public sector, understanding such trade-offs can help policymakers focus on the 20 percent of a service that is “just good enough” to allow for radical savings.

How can these trade-offs be broken?

Disruptive innovation is about finding new business models that allow you to break traditional trade-offs. Such models typically combine a disruptive idea with a technology that can propel the innovation forward, into ever-greater capabilities.

A market analysis of how other public and private sector organizations are fulfilling the job-to-be-done in different ways can illuminate innovations that break the trade-offs. It’s particularly important to examine innovations in the broader commercial sector, as those will often be overlooked (think of the impact email has had on government portal services). It’s also critical to understand that the disruptive approach will likely start off worse than the current dominant model (but then improve over time).

One way of developing a disruptive idea is to formulate a disruptive hypothesis.

Disruptive innovations trade off pure performance in favor of simplicity, convenience or affordability … they offer ‘good enough’ solutions at a lower price.—Dr. Rod King, author of Business Genomics

What is the enabling technology?

Disruptive innovations nearly always involve the application of a rapidly improving technology. The technology enables existing trade-offs to be broken, gaps between the real and the possible to be closed, and the vision of the disruptive hypothesis to be made a reality. The key is to find a low-cost emerging technology that is rapidly improving, and match it with a solution that meets the disruptive business model.

For Southwest Airlines, the technology was a new, more efficient aircraft that allowed them to scale their point-to-point business structure to longer flights.124 Because Southwest uses only one type of plane, flight crews only need to know how to service one type of aircraft, making maintenance faster and more efficient than its competitors.

For Netflix, the enabling technology that enabled it to disrupt video rental stores was first the Internet and the company’s recommendation algorithm. Then it was improved broadband speeds and Wi-Fi devices that allowed for video streaming.

For electronic monitoring, the technology was first Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags and then rapidly improving GPS technology. For education it is online learning. For intelligence, analytics technologies may enable open-source intelligence to eventually disrupt traditional intelligence methods.

One government agency constantly searching for disruptive technologies that can break existing trade-offs is DARPA. Small satellites today, for example, are increasingly capable of doing the same things as large satellites, but they are also extremely expensive (up to $30,000 per pound to launch) and have to “go to orbits selected by the primary payload on current launchers, rather than to the orbits their designers and operators would prefer,” said Mitchell Burnside Clapp, DARPA program manager.125 The agency hopes to break these trade-offs and put satellites into orbit for less than one-third of this cost. How? An aircraft would carry the small satellite and then, once it reaches the desired altitude and direction, release the satellite and booster to continue its climb into space. A host of technologies identified by DARPA might enable this to happen.126

What is your “disruptive hypothesis”?

Luke Williams, the author of Disrupt, defines a disruptive hypothesis as “an intentionally unreasonable statement that gets your thinking flowing in a different direction.”127 Disruptive hypotheses, formed correctly, can help policymakers see radically different ways of getting a job done.

To develop such a hypothesis, Williams suggests first exploring the dominant clichés in the area in question and then inverting or denying them.128 To see how this might work, let’s return to the education example. It is typically assumed that public schooling requires:

- In-person teachers

- Classrooms

- Textbooks

- School facilities

- Cafeterias

- Transportation

A disruptive hypothesis might ask: “What would happen if we tried to educate children without any of these elements?”

What might a different model look like? The answer is that it might look pretty similar to the virtual charter schools now operating in 30 states and educating nearly 250,000 students across the United States.

UAVs provide another example. Before the introduction of UAVs into military and intelligence operations, the prevailing clichés held that sophisticated offensive air operations would require:

- A pilot in the cockpit

- Expensive fuel and maintenance costs

- Possibility of human error

- 10 hours maximum flight time

- Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) planes to provide warning and control

- Long runways or carrier take-off capabilities

Could we have imagined, two decades ago, a model of military air operations that involved no onboard pilots, no large ground crews, days of uninterrupted flight time, very low maintenance and fuel costs, and no need to use ground assets for targeting? Some innovators did. The result: UAVs.

Shape: How and when to start disrupting

Every gardener knows that simply covering seeds under a bit of soil doesn’t guarantee a bountiful garden. A multitude of factors must be considered—water, sunlight, temperature, weeds, and insect pests—and often the needs of each type of seed are different.

The situation is the same for positioning innovative ideas. An organization must identify the right set of growing conditions to cultivate its innovation.

The best place to start disruptive innovation tends to be in a market segment that is vastly overserved or not served at all by the current, dominant model of delivery.129 The disruptor can’t focus on disrupting the core mission area initially because at the beginning a disruptive solution usually cannot compete with the incumbent solution.

Returning to transport security, if you were looking for a place to test and incubate a new and cheaper way of screening travelers, it would be wise to start with a place other than airports where billions of dollars have already been spent to protect the flying public and keep explosives off planes. The perceived political and security “riskiness” of introducing a “less good,” lower-cost alternative in this arena would probably make the effort a non-starter.

A better option for testing a new model might be somewhere that doesn’t even have a system to screen passengers, such as a municipal subway or bus system.130 The lack of an existing solution might cause local transit administrators to be more accepting of a radically new approach than airport security administrators.

Start the innovation in an unserved market

The upward climb of UAVs demonstrated the value of starting the innovation in a largely unserved market. The CIA developed UAVs for surveillance in the early 1990s. With its quiet operations, long flight time, and lack of any need for a human pilot, the UAV perfectly fit the needs of a clandestine intelligence-gathering agency.

And the UAV had little competition from traditional intelligence. After all, it wasn’t always feasible to deploy human agents on the ground, and satellite or high-altitude imagery was expensive and sometimes too inconsistent for the CIA’s demand for real-time geospatial intelligence. These factors made the CIA a good test bed for investigating the emerging capabilities of UAVs.

Similarly, the best region to really test the full capabilities of an open-source intelligence model is probably not high-profile areas like China, Russia, or the Middle East. Instead, proponents might look for a region of the world currently underserved by intelligence community resources, such as Africa. Or, alternatively, it could be used in a region where the pace of events exceeds the capabilities of traditional intelligence. Thus the intelligence community could incubate open-source and advanced data mining and analysis activities in underserved markets, and use them to guide the collection of intelligence information from traditional sources.131

Autonomy

Shaping a successful disruptive innovation also typically requires the disruptor to have autonomy from the parent organization, the mainstream market it will disrupt, and the incumbents who dominate the market. Disruptions threaten existing practices. They will typically be squashed or watered down if the disruptors don’t have the autonomy to experiment with the model and then drive it upwards.

This means that disruptive innovations impacting the public sector will typically originate outside of large government organizations. The job of government officials is then to support these efforts and protect them from efforts by incumbents to kill them through regulation or similar means.

After identifying where to test and pilot the disruptive innovation, the next step is to grow it and extend it into core operations.

Disruptive innovations impacting the public sector will typically originate outside of large government organizations.

Grow: Nurture and extend the disruptive innovation

Disruptive technologies can transform whole industries and create entirely new markets and business models. For these disruptions to take root, however, they must be fostered and protected. Herein lies another advantage for leaders in the public sector. Government has an array of tools and channels that can be used to foster the growth of disruptive technologies.

These tools and channels include legislation, budget maneuvers, and other special funding tools. For example, Florida legislation encouraged the growth of electronic monitoring after the 2005 passage of Jessica’s Law, which mandated electronic monitoring for sexual offenders, and helped propel the adoption of GPS technology for electronic monitoring.