The road to value-based care has been saved

The road to value-based care Your mileage may vary

21 March 2015

Value-based payment models for health care have the potential to upend traditional patient care and business models. What can your organization do to effectively make the shift?

Executive summary

The market shift toward value-based care (VBC) presents unprecedented opportunities and challenges for the US health care system. Instead of rewarding volume, new value-based payment models reward better results in terms of cost, quality, and outcome measures. These largely untested models have the potential to upend health care stakeholders’ traditional patient care and business models. The level of dollar investment in VBC is substantial and some health care organizations are actively preparing for the transition to VBC while others are hesitating. Their reluctance to shift to VBC is understandable: The level of financial investment is substantial and the current fee-for-service (FFS) payment structure is still highly profitable for some. The shift has already begun in some markets, though, to build key capabilities. As other organizations plan their route to VBC, it is important to understand that there is no single, “right” payment model that fits all situations. Experience gained in markets where the shift to VBC is under way shows that the transition is much like a road trip—different routes and modes of transportation can get travelers to their destination. By implementing a holistic process and leveraging robust supporting data—much like following a GPS system—a health care organization can develop payment models that work for individual situations and populations. There are many road tests, routes, and transportation modes available. Determining the best “route and transportation mode” with VBC is challenging given the many and differing options. When considering how to effectively operate under the payment models, organizations should take stock of their market position and core capabilities. For example, examining spending variation may highlight areas where payers and providers can focus to deliver on VBC’s promise. A sample accountable care organization (ACO) model depicts one potential approach for successfully structuring across providers to share risks and benefits. Health care stakeholders should understand how the various models work, including their associated incentives, risks, and potential financial impacts. Pressure to reduce costs and improve quality and outcomes are likely to continue. Health care providers that start to develop VBC models now may gain early advantages that will enable them to compete more effectively in the future. When the market shifts further toward value, those not ready may be left behind while those on their road trip may be well positioned. Understanding how the models work is a first step. How to embark upon the road trip depends on each stakeholder’s selected route.

Traveling the road to value-based care

The shift by US health care organizations toward VBC is a lot like taking a road trip to a never-before-visited destination via never-before-traveled roads. Some organizations do not know which route to take; others are not sure they even want to leave home. Many physicians, health system executives, and other stakeholders agree that the journey is unavoidable—the transition from traditional FFS toward payment models that promote value is happening. In some markets, it has already occurred. Stakeholders are investing major dollars and adoption is increasing. Value-based payment models aim to reduce spending while improving quality and outcomes (see sidebar). According to a 2014 survey, 72 percent of surveyed health executives said that the industry will switch from volume to value.1 In addition, a Deloitte 2014 survey of US physicians found that, although many have limited experience with value-based payment models, they forecast half of their compensation in the next 10 years will be value-based.

The shift to value-based care

The US health care system’s current FFS-based payment model offers incentives for providers to increase the volume of services they furnish. Although providers have professional goals of improving health outcomes, the FFS model does not reward them for this. Due to concerns about rising costs and poor performance on quality indicators, employers, health plans, and government purchasers of health care are pushing for a transition to value-based payment models. The premise of value-based payments is to align physician and hospital bonuses and penalties with cost, quality, and outcomes measures (see appendix A for more detail on drivers).

Drivers of the shift to value-based payments include unsustainable costs, stakeholders’ push for value, and federal government support for new payment approaches. Additionally, new laws and regulations, more robust data, increased health care system sophistication, and risk mitigation approaches are accelerating the pace of change (see sidebar and appendix B for more detail).

What are value-based payment models?

Health care organizations are experimenting with variations and combinations of four main types of value-based payment models (see appendix B for detailed descriptions of the models).

1) Shared savings—Generally calls for an organization to be paid using the traditional FFS model, but at the end of the year, total spending is compared with a target; if the organization’s spending is below the target, it can share some of the difference as a bonus.

2) Bundles—Instead of paying separately for hospital, physician, and other services, a payer bundles payment for services linked to a particular condition, reason for hospital stay, and period of time. An organization can keep the money it saves through reduced spending on some component(s) of care included in the bundle.

3) Shared risk—In addition to sharing savings, if an organization spends more than the target, it must repay some of the difference as a penalty.

4) Global capitation—An organization receives a per-person, per-month (PP/PM) payment intended to pay for all individuals’ care, regardless of what services they use.

Payers and other stakeholders are making significant investments in VBC initiatives:

- Aetna dedicated 15 percent of its 2013 spending to VBC efforts and intends to grow that amount to 45 percent by 2017.3

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) appropriated $10 billion per year for the next 10 years for innovation efforts, many of which center on forms of VBC.4 These include the Pioneer Accountable Care Organization (ACO) model, Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), and Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI).

- Blue Cross Blue Shield health plans spend more than $65 million annually, about 20 percent of spending on medical claims, on VBC.5

Participation in value-based payment models is growing:

- The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) set a goal of tying 30 percent of payments for traditional Medicare benefits to value-based payment models by the end of 2016 and 50 percent by 2018.6

- Two hundred and twenty organizations participated in the MSSP in 2014.7

- Nearly 7,000 organizations participate in the BPCI.8

- Twenty health systems, health plans, consumer groups and policy experts formed the Health Care Transformation Task Force, and aim to have 75 percent of their business based on value by 2020.9

Marketplace test drives

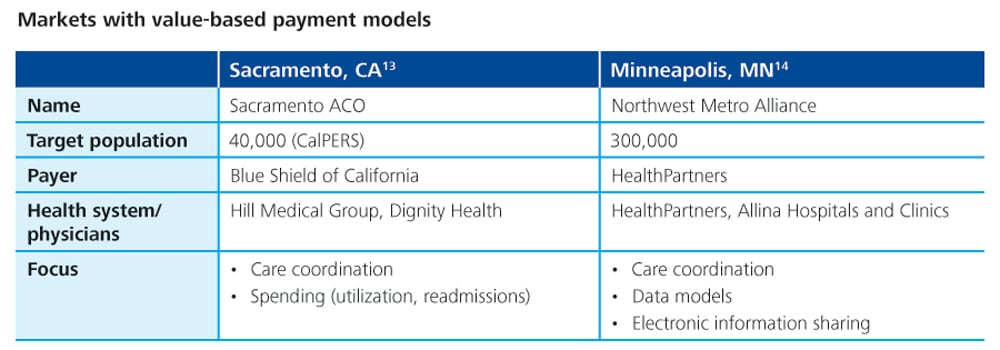

Some US health care providers have already adopted value-based payment models. Others are still determining whether they should make the transition, since their revenue relies largely on traditional FFS payments. Still others have chosen to “test drive” value-based payment models before full adoption. Two examples of the latter are the Sacramento ACO and Northwest Metro Alliance in Minneapolis (see sidebar for details). These test drives offer examples of what other organizations may launch into on a broader scale. They also paint a picture of the collaboration required across stakeholders. Both targeted populations in regional markets where they utilize physician alignment and care coordination to achieve value. Health plans, health systems, and physician groups were travel partners in each of these ACOs. The Sacramento ACO was comprised of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), a physician group (Hill Medical Group), and a health system (Dignity Health). The ACO’s goal was to develop a competitive entity for reducing costs and improving quality.10 The result of this test drive was $59 million in savings to CalPERS in its first three years.11 The Northwest Metro Alliance was formed by health plan provider HealthPartners and the physicians and hospitals of Allina Hospitals and Clinics. It had similar goals, and saw the ACO’s cost of care decline to 90 percent of the market average.12

Biopharmaceutical companies (biopharma) and medical technology (medtech) companies are also engaged in test drives. Their value-based payment model activity involves collaborations with providers and health plans on specific populations. Several biopharma companies have been partnering with health plans to test drive value-based payment models targeting drugs and interventions for specific populations, such as diabetes and non-spinal fractures. Payments are based on outcomes and quality performance.15 Medtech companies, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, and Medtronic, are exploring risk-based payment models with providers. Some arrangements include potentially paying a rebate to providers if a device does not meet performance goals. Other arrangements are considering assuming a portion of a hospital’s readmissions penalty if, for example, a patient implanted with a cardiac device is readmitted for heart failure.16

Which route is best?

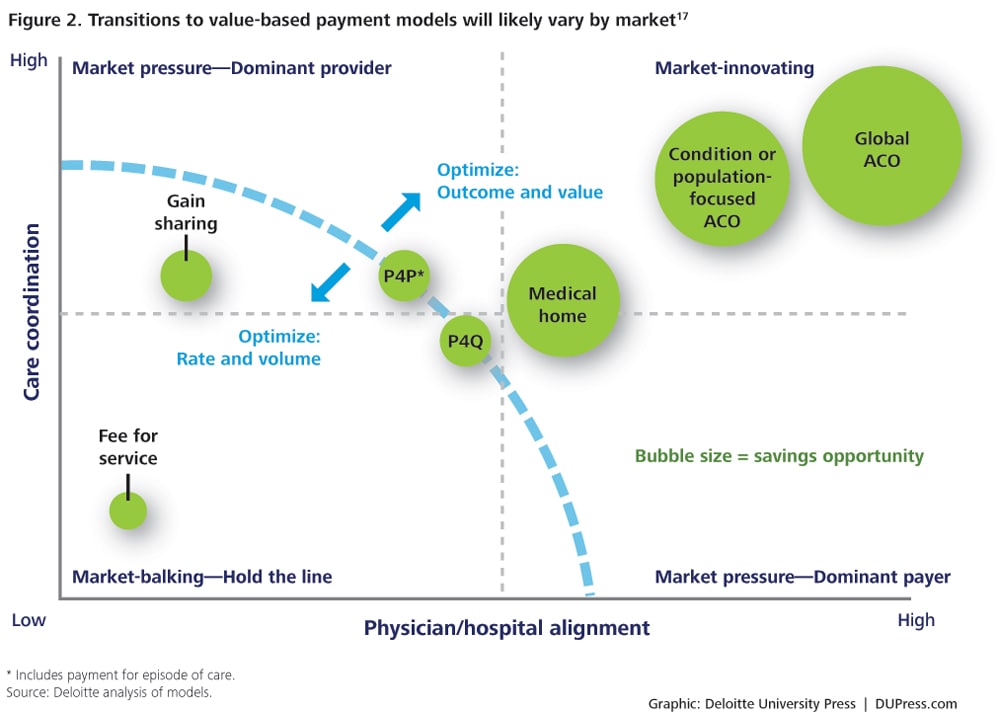

Much like any first trip to a new destination, the journey to VBC can be filled with uncertainties. A traveler may use a GPS system to identify several alternative routes, yet find that the shortest way has unexpected traffic jams, speed traps, or other delays that a longer route avoids. Similarly, a “GPS-like” approach (figure 1) could identify a variety of routes for organizations starting their journey to VBC, but each may vary in length and require different capabilities, partnerships, and investments along the way.  In addition to taking test drives, health care organizations may adopt incremental, value-based payment models to ease their transition. Industry observers anticipate that the use of value-based payment models will begin with methods like shared savings and pay for performance, which involve limited financial risk for providers. Organizations and their payment models then may transition more fully to VBC over time as they develop more experience and a tolerance for financial risk (see sidebar and appendix B). For those planning to take the road trip to its ultimate destination, some observers expect that value-based payment models which create both potential bonuses (upside risk) and penalties (downside risk) would be most likely to demonstrate results. However, models combining more financial risk plus more potential upside are likely to prompt wary providers to first take a test drive. Once models with both upside and downside risk become more prolific, it is anticipated that adoption will increase for payment models involving full financial risk for providers with an enrolled population, such as a global capitation for ACOs, or significant risk-sharing with payers (figure 2). Global capitation and ACO models require the highest levels of care coordination and physician/hospital alignment. Moreover, adoption is most likely to occur in markets where “travel partners” are well-suited; for example, where physician/hospital alignment is greatest and capabilities around care coordination (which requires both data and clinical integration) are strongest.

In addition to taking test drives, health care organizations may adopt incremental, value-based payment models to ease their transition. Industry observers anticipate that the use of value-based payment models will begin with methods like shared savings and pay for performance, which involve limited financial risk for providers. Organizations and their payment models then may transition more fully to VBC over time as they develop more experience and a tolerance for financial risk (see sidebar and appendix B). For those planning to take the road trip to its ultimate destination, some observers expect that value-based payment models which create both potential bonuses (upside risk) and penalties (downside risk) would be most likely to demonstrate results. However, models combining more financial risk plus more potential upside are likely to prompt wary providers to first take a test drive. Once models with both upside and downside risk become more prolific, it is anticipated that adoption will increase for payment models involving full financial risk for providers with an enrolled population, such as a global capitation for ACOs, or significant risk-sharing with payers (figure 2). Global capitation and ACO models require the highest levels of care coordination and physician/hospital alignment. Moreover, adoption is most likely to occur in markets where “travel partners” are well-suited; for example, where physician/hospital alignment is greatest and capabilities around care coordination (which requires both data and clinical integration) are strongest.

See endnote 17

An important consideration: Spending variation

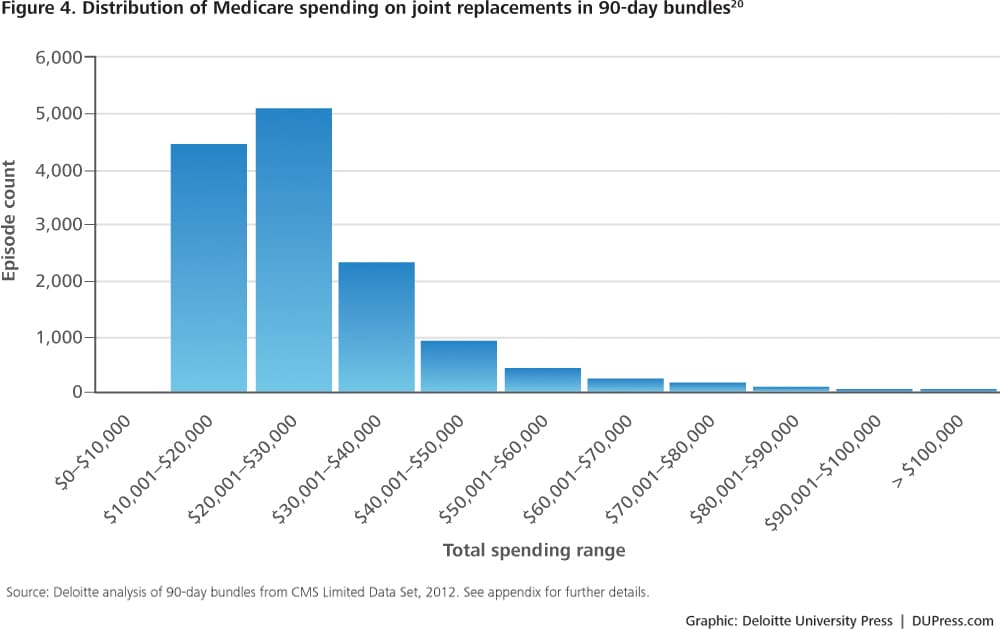

VBC rests on the premise that there are opportunities for industry stakeholders to reduce costs. Before entering into value-based payment arrangements, therefore, providers should consider identifying cost- and quality-based opportunities for achieving better value. One potential area for improvement is spending variation. Numerous studies have documented spending variation across geographic regions for the same health care services. Some studies show spending for the same condition (with the same quality results) varies by up to 30 percent,18 suggesting that this amount could be saved if the right incentives and capabilities are in place. Of course, it takes time to realize system improvements; a more realistic goal might be 5–15 percent savings generated over three to five years. Variation in Medicare spending for joint replacement, for example, shows potential savings opportunities in the areas of care management and patient settings (figures 3 and 4). Deloitte analyzed Medicare data to see how much variation exists for this type of common and costly hospital procedure. Data is from the Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services’ (CMS) Limited Data Set, which includes a representative sample of claims data from randomly selected Medicare members. This particular dataset is especially useful for analyzing bundled payments (see appendix C for further methodology details).

See endnote 19

See endnote 20

Deloitte’s analysis found opportunities for savings if organizations can reduce variation in care delivery and thereby reduce variation in spending—the difference between the median and mean for a type of episode is one indicator of the overall potential. For example, for Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) 470, the most common type of hospitalization related to joint replacement, there is a 17 percent difference between the median and the mean (figure 3). This analysis explored the elements of spending both during and after the hospital stay to gain insights on the drivers of variation. For joint replacement, the variation in spending after the hospital stay and readmission is primarily driven by Part B drugs and medical technology (durable medical equipment [DME]), despite their being small portions of the total cost. Implementation of value-based payment models may require looking at data on spending components to understand the potential savings opportunities. This might include, for example, spending on pharmacy (Deloitte’s analysis only includes specialty drugs paid through Medicare Part B) or care which is provided over a longer period of time. Such an analysis might capture more variation in physician service use beyond the 90 days post service. In addition, clinical expertise should be applied with data analysis to understand how to appropriately realize identified savings without hurting outcomes. This is usually an iterative process with physicians to gain a shared understanding of what is causing the variation, and what can be done about it clinically.

Ready for a road trip?

On the road trip to VBC, providers generally do not travel alone—fellow travelers may include payers, other health care providers, and ancillary service providers (for example, post-acute providers and biopharma companies). The stakeholders should be aligned toward the shared goal of value. Shared savings arrangements are emerging that better align incentives and encourage engagement among these stakeholder types. Here is an illustrative scenario (figure 5): an ACO that consists of a hospital and primary care and specialty physicians serving 1,000 patients. The scenario illustrates how value-based payments can be shared to engage multiple stakeholders. The modeling assumes—which is typical—that the payer (for example, a health plan) provides the ACO a bonus if it can reduce total spending by 5 percent. If the ACO generates savings, it can distribute the resulting bonus in a way that helps each type of provider sustain a reasonable margin.

See endnote 21

Within the illustrative ACO:

- Some of the highest spending was for hospital care (as is typical), followed by specialists and primary care physicians. The ACO agreed that most of the savings, therefore, would come from lower spending on hospital care (6 percent) and specialist care (4 percent).

- The ACO realized these savings—possibly by increasing its investment in primary care and better managing chronic conditions. It kept some funds (33 percent) for future investments. The remainder was shared among participating providers.

- Because of hospitals’ disproportionate share of spending, this example illustrates that a small share of these savings greatly rewards physicians.

- Hospitals may need to increase market share in order to be made whole financially since they lose revenue unless they can eliminate the excess capacity that is generated by enhancing care coordination. This example emphasizes the importance of pricing risk-sharing deals to a market-competitive medical expense per-member/per-month payment in aggregate.

Don’t forget to pack

Just as travelers on an extended road trip require supplies such as fuel, maps, snacks, and other supplies, stakeholders on a VBC journey might require capabilities such as care coordination, clinical integration, and physician alignment. Figure 6 summarizes some of the capabilities needed for value-based payment models versus FFS, based on Deloitte’s analysis and synthesis of pertinent literature. For example, more robust administrative capabilities may be needed to support value-based payment models. Also, as health systems assume more financial risk, they may decide to take over certain care coordination, disease management, data analysis, and administrative functions from a health plan (or other payer). Some health plans are offering support (as well as value-based payment models) to help health systems do this. Ultimately, there is no single “right” route or transportation mode for the trip to value-based payments—in fact, a provider may change routes or vehicles/models along the way. Starting the process of getting to an equitable, risk-mitigated, aligned incentive model is what is important. This process requires a strong market, target population, and clinical data to determine what price point will result in a competitive rate and an appropriate share/target for each involved party. The process also requires informed physician and hospital leadership armed with data that can show what is needed to get to this price point, financial scenarios that illustrate a feasible path forward, and an opportunity analysis that demonstrates how savings can be generated. Some organizations may lack the necessary capabilities for certain value-based payment models (figure 6), making those models “closed roads” which require a detour or “car-pool-only lanes” which require a partner.

See endnote 22

When evaluating potential payment models, a provider’s approach may consist of:

- Understanding their market position

- Assessing their capabilities

- Conducting a financial analysis

- Aligning around opportunities

Implications for travelers

The implications of more widespread use of value-based payment models vary by stakeholder:

Health systems/hospitals

Many health systems and hospitals are developing ACOs and other partnering arrangements to implement value-based payment models. Some may do this to get preferential market share through arrangements with payers. Other systems are less heavily involved, reflecting less pressure to do this in their markets. As providers evaluate their strategies, they should consider how well-equipped they are to successfully reduce spending while maintaining quality and access in areas such as readmissions and ancillary services. Certain value-based payment models may require more sophisticated IT platforms, extensive data analytics, and planning. Some health systems and hospitals may lack such capabilities and, therefore, need to invest in new systems and processes or partner with others that already have them. In addition, providers may need the financial acumen to understand the risks involved with each particular payment model.

Ancillary providers (for example, post-acute care providers, biopharma, medtech, and supply companies)

Ancillary providers may undergo considerable scrutiny as health care organizations implement value-based payment models. Hospitals and health systems will likely be looking for partners and suppliers that can offer lower prices, reduce spending (either overall or for a service bundle), and contribute to better quality scores and outcome measures. If a post-acute care organization can demonstrate that its care management techniques result in lower hospital readmissions or a pharmaceutical manufacturer can bundle its product with a successful disease management approach that improves quality ratings, they will be viewed as a preferred partner relative to ancillary providers operating under “business as usual.” In addition to providers and payers, biopharma and medtech companies have started to test drive value-based payment models with other stakeholders. As adoption grows among these ancillary providers, they also will need to determine which travel partner and route to take.

Destination: A model that delivers on value

The market shift to value-based payment models is inevitable, driven by the pressure to reduce costs and improve quality and outcomes. Employers, health plans, government payers, and consumers are asking the health care system to deliver on value; these new payment models are a fundamental component of that process. There is no single “right” approach that will work for all stakeholders or in all markets. The choice of model (or combination of models) will depend on each stakeholder’s capabilities, market position, financial situation, and VBC goals. Advantages to early participation by health care providers that start to develop value-based payment models now include greater experience and market share. They can gain core competencies to participate successfully in the future and may gain increased market share, as a first mover in the market, from health plans. When the market shifts further toward value, those not ready may be left behind while those on their road trip may be well positioned. The pressure will likely only get stronger to shift toward more complex and financially risky payment models. Whether they decide to travel solo or with partners, health care organizations that leave now on their trip to VBC can put in place the necessary capabilities and processes that may give them first-mover advantage and increased market share, while others may be left behind.

Appendix A: Drivers of the shift toward value-based payment models

- Unsustainable costs and awareness of potential for savings: In 2012, the United States spent $2.8 trillion on health care, representing nearly 17 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).23 According to estimates, spending will reach nearly $5 trillion (20 percent of GDP) by 2021.24 The FFS payment model for health care is considered one of the major drivers of high costs because it encourages the use of more services (and expensive ones).25 Spending variation is also a concern; consumers with similar conditions/procedures experience wide variation in services and resulting expense.26 The variation—not explained by differences in quality—suggests an opportunity for savings if providers adopt more consistent approaches to care that are shown to be both effective and efficient.

- Recognition that FFS drives volume, not value: The current FFS system largely fails to financially reward high-quality or coordinated health care across providers. The incentive with FFS is to provide more services and treatment, as payments are dependent upon quantity, not quality. Value-based payment models change incentives to focus on value by rewarding better outcomes and lower spending.

- New laws, regulations, and pilots: The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 reflected purchaser (employers, health plans, government payers, and, increasingly, individuals) concerns about costs and their goals for better value. It included a permanent program in Medicare that allows organizations to choose to participate in accountable care organizations (ACOs) using shared savings/risk payment models and pilots for bundled payments. Both are examples of payment models that are intended to stem spending and improve quality and coordination. Other examples include broadened use of pay for performance in traditional and managed Medicare programs and readmission penalties for hospitals.

Appendix B: Description of payment models

See endnote 29

Appendix C: Methodology for analyzing joint replacement spending

The methodology leveraged the CMS Limited Data Set:

- The sampled dataset includes the claims of 5 percent randomly selected members.

- Data is for 2011, the most recent year available from CMS, without inflation adjustment.

- Pharmacy claims are not part of the CMS dataset.

- The dataset excludes members in Medicare Advantage, as their claims are not included in the CMS dataset.

- The dataset excludes dual-eligible members.

Defined episodes of care are based on the following:

- Episodes use the CMS definition from its Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative.

- Episodes are triggered by specified inpatient admission, as defined by Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) codes.

- Episodes include trigger admission, professional, outpatient, and ancillary services during admission, and all related post-discharge services (defined by CMS) within 90 days after discharge.

- Unit cost is normalized for geographic variation (for example, wage index difference).

- The summary excludes supplemental payments, such as Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH), Indirect Medical Education (IME), capital payment, and so on.