Power and Interest Grids - Making Governance Fun has been saved

Perspectives

Power and Interest Grids - Making Governance Fun

Exactly 40 years ago, the music singles charts featured ‘You Make Loving Fun’ by Fleetwood Mac. This article discusses a tool which can make governance fun.

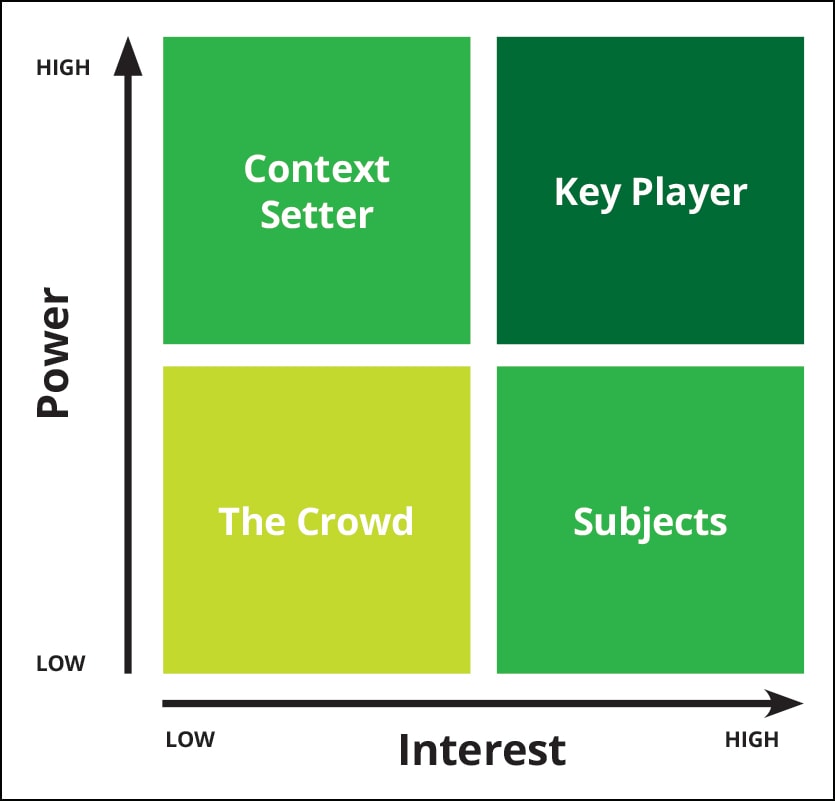

Governance can be defined as ‘the system of rules, practices and processes by which an organisation is directed and controlled’. So, it’s unsurprising that discussions around this topic can often be mechanistic and dry. For a more street-wise understanding, it helps to examine life as it is. Real world discussions around practical governance matters should consider behavioural factors and situation organisational dynamics. This brings me directly to Eden and Ackerman’s power / interest grid, an important and useful stakeholder mapping tool which considers motivations and ability to influence. To deploy the grid, first you must identify your various stakeholders and map them on the following matrix according to their relative power and interest.

View the image: Stakeholder Power / Interest Grid

You will find that stakeholders land in one of the grid’s quadrants. That location can then be used to guide the way in which to approach the management of these stakeholders as follows:

- Key Players having both high levels of power and interest need to be managed closely, probably involved in important decisions and definitely engaged on a regular basis.

- Context Setters have power, but have relatively low interest. The optimal approach is to attract as little of their attention as possible. Keep them satisfied.

- Subjects, on the other hand, are highly interested but relatively powerless. They can be kept happy by keeping them informed.

- In the opposite quadrant are The Crowd - relative bystanders with limited interest or power. Usually, monitoring of these stakeholders is sufficient.

These grids can be developed from an organisation’s point of view, or for the Machiavellian amongst you, from your personal standpoint from within an organisation. Whatever your perspective, the grid can be used to prioritise your efforts.

What I find particularly fascinating about conducting this type of analysis is that even across homogenous organisations one can generate wildly divergent results. A classic example would be football clubs. At first glance, here are a group of organisations with very similar goals (pun intended) and facing similar market pressures (e.g. securing and maintaining talented footballers at a reasonable price). And yet, should you carry out a stakeholder analysis from the point of view of the club manager, you can come up with highly divergent results across clubs and across time.

Between 2008 and 2013, Chelsea Football Club ‘let go’ of seven managers, with many of the casualties being amongst the highest profile names in the profession. At Chelsea, player power is widely regarded to have been a key factor behind some of the managerial churn, with senior players such as John Terry and Frank Lampard calling the shots. Six miles away, at Arsenal, the story is markedly different. Arsene Wenger has been the manager for over 20 years, and whilst the early years were marked by success on the field, in footballing terms his recent years at the helm have been patchy to say the least. At Arsenal, the ‘key players’ are in fact the club owners, who appear to value financial stewardship over footballing results and have been impervious to outbreaks of player unrest or supporter discontent.

In the case of the England team manager - one of the top jobs in football management – history hints at the importance of the media. In 1999, Glenn Hoddle was ‘let go’ after placing his unorthodox religious views into the public domain. Steve McLaren struggled with the media before departing after being dubbed the ‘Wally with a Brolly’ by the Daily Mail following his final match. In 2016, Sam Allardyce lasted exactly one match (a win) after being caught out by a media sting operation. Many commentators say that fear of press criticism has prevented English managers from taking difficult but necessary footballing decisions.

To apply this model to a complete different domain, let’s look at events in foreign affairs. Whatever else you may think of Robert Mugabe – many will describe him as an unpleasant dictator who has inflicted extreme damage to the country he has ruled for the last 40 years – he has certainly been effective at maintaining power. Over the years, Mr Mugabe has been effective at shrugging off international condemnation and suppressing internal opposition. How did this effective stakeholder manager finally slip? It appears to have been caused by his failure to manage Zimbabwe’s military top command. With their man, Emmerson Mnangagwa, a heartbeat away from the Presidency, they were not prepared to accept his removal as Vice President earlier this month and had both the incentive and the power to rebut President Mugabe. Mugabe failed to manage a key player effectively.

Working within a team of internal audit practitioners at Deloitte Malta, we are often asked to set up internal audit functions as part of wider corporate governance overhauls. Inevitably, as I speak to directors, managers and staff at these organisations, I am briefed on the idiosyncrasies and challenges of their organisation – and it’s true, every organisation is unique. However, with the power interest grid model, I think you will find that even the most complex organisations bear analysis. A power interest model can be a useful way to develop managerial strategies and harness the necessary support to implement them. It can also be a way of identifying the dominance of stakeholders and designing corporate governance arrangements which take the edge off that risk.

In Malta’s corporate world, not to mention civil society, governance is a hot topic – and it need not be boring.