United States Economic Forecast has been saved

United States Economic Forecast 2nd Quarter 2016

16 June 2016

Notwithstanding chatter on cable TV, today's US economy is comparatively stable and borderline dull. Yes, volatility threatens in Europe and China, and the presidential election is raising temperatures, but we expect the gradual upturn to continue, hampered by nagging slow productivity growth.

As an economy fluctuates, so do economic measures. That may seem an innocuous truism, but it’s amazing how often even experienced observers of the economy forget what it really means. When times are good, the rate of economic growth might be high or even very high; in bad times, the economy can still sometimes register an upbeat quarter, at least according to the data. And when the economy is growing moderately, as it has for the past few years? Fluctuations within the “normal” range mean that in one month the economy might appear ready to burst out of its doldrums and, the next month, about to plunge into recession—while most economists stick with their normal range prognosis.

As an economy fluctuates, so do economic measures. That may seem an innocuous truism, but it’s amazing how often even experienced observers of the economy forget what it really means. When times are good, the rate of economic growth might be high or even very high; in bad times, the economy can still sometimes register an upbeat quarter, at least according to the data. And when the economy is growing moderately, as it has for the past few years? Fluctuations within the “normal” range mean that in one month the economy might appear ready to burst out of its doldrums and, the next month, about to plunge into recession—while most economists stick with their normal range prognosis.

But pundits often find those monthly and quarterly shifts, however minor, irresistible material for discussion. After all, the talking heads on 24/7 cable TV need to say something, and it’s a lot more exciting to talk about doom and gloom—or the excitement of a “new economy”—than to tell the truth . . . which is that the economy is really pretty boring right now.

The end of 2015 and early part of 2016 saw quite a bit of data to support the doom-and-gloom storyline; the 1 percent average GDP growth in 2015Q4 and 2016Q1 is undeniably sluggish. But two quarters below trend don’t constitute a recession, and few people have seen much of an impact. Notwithstanding a disappointing monthly report in early June, job growth has remained strong despite a decline in industrial production and flattening of some measures of residential construction. In a few months, those TV pundits may well be talking about a new boom.

This doesn’t mean that the US economy is all hearts, flowers, and unicorns. Stubborn problems persist, such as:

- Foreign economic conditions continue to be a source of potential concern. China’s GDP growth increasingly seems to be held up by a growing web of debt—and debt cannot continue to grow indefinitely.1 Exactly what might happen if China’s economy crashes is uncertain, but it would hardly strengthen the US economy. Meanwhile, Europe remains in the headlines. The first quarter saw faster Euroarea GDP growth than in the United States, but the looming British vote on whether to exit the European Union creates ongoing uncertainty. And EU authorities are still working to address issues with Greece.

- Global monetary policy has entered a new phase. Some 23 percent of global GDP is now being produced in economies with negative short-term interest rates, challenging economic analysts around the world.

- Geopolitical conditions have been (relatively) quiet recently, but several wars in the Middle East, involving a confusing array of fighting factions, threaten to pull in the major powers. Russia-Ukraine tensions may not be regularly making Western headlines, but skirmishes could escalate anytime. And these geopolitical problems could push up oil prices and create additional challenges for policymakers and the US economy (albeit some relief for a few oil-producing countries and US states).

- House and Senate leaders have reiterated that they intend on ensuring that the government is funded for the next fiscal year. However, they have had trouble putting those intentions into action. Following the abandonment of budget resolutions, the normal appropriations process has stalled. Congress will likely end up needing to pass a comprehensive “omnibus” reconciliation bill at the last minute, and fervent, obstinate political opposition to last year’s budget compromise leaves open the possibility of a government shutdown in the middle of the presidential election.

- Elections in Europe and in the United States indicate an unusual level of distrust with current political leadership and institutions. It’s unclear what this means for economic growth, but at the very least, the electoral volatility may present business with higher-than-usual political risks.

- If you thought that political uncertainty was the biggest factor holding back the American economy, however, consider this: US (and global) productivity growth remains very low, with no sign of an upturn, and experts have as yet reached no consensus on why this is the case. This slow growth contributes to difficulties addressing the country’s long-term budget issues—and helps to suppress wages, perhaps exacerbating today’s political unrest.

Beware of the too-easy statement that risk is greater than in the past. Businesses faced extremely high levels of uncertainty in periods such as the early 1970s (with the Arab oil embargo and transition to floating exchange rates) and the financial crisis just six years ago. Today’s risks are different, but they are hardly greater. The balance of risks, however, looks biased toward things that could go wrong; that’s why Deloitte’s forecast judges the potential risk of slower growth to be greater than the risk of faster growth.

This doesn’t make for especially colorful banter between TV pundits. It does, though, create an environment in which well-timed and careful investment can still be profitable, and in which the probability remains high that job growth and the economy will stay relatively healthy.

Scenarios

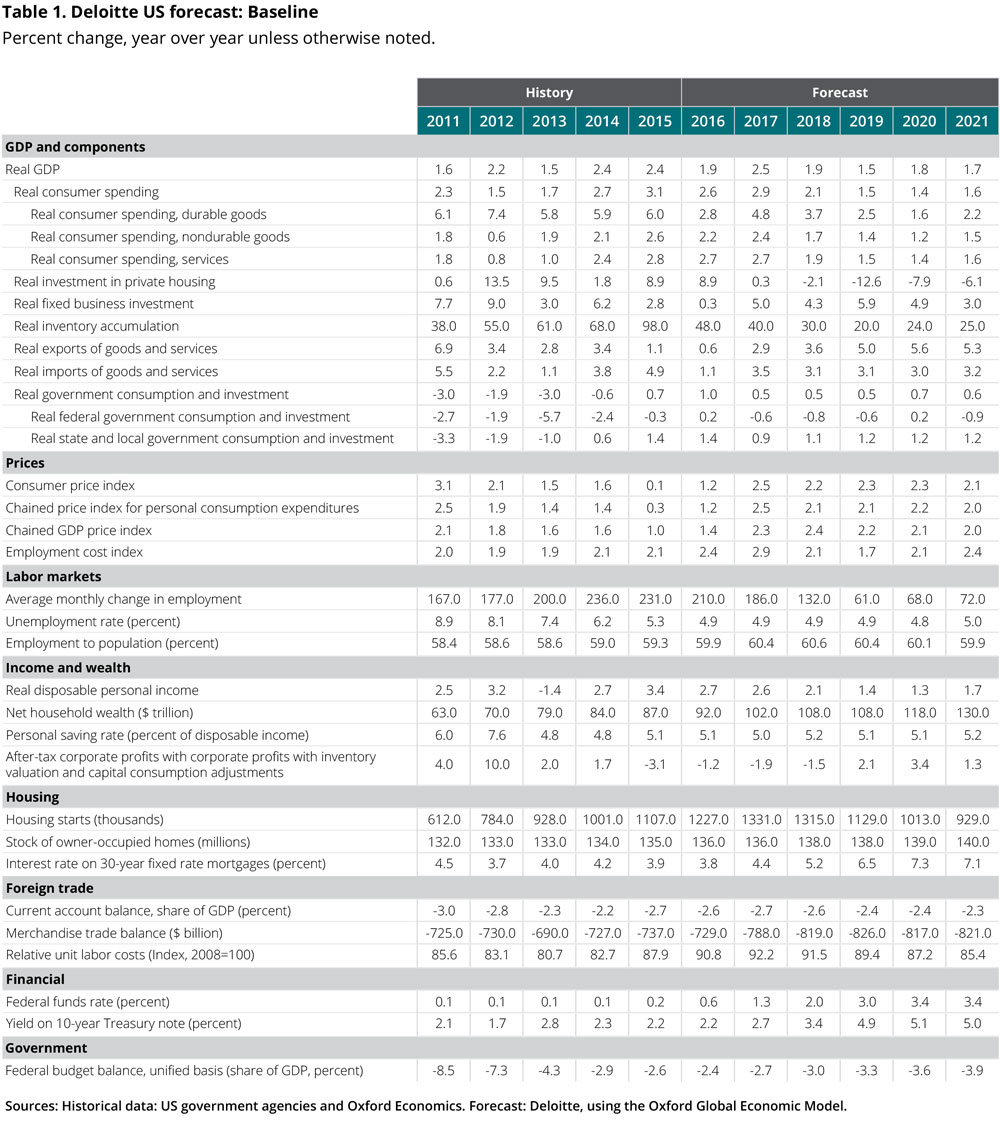

There are plenty of reasons why actual economic growth might be better or worse than Deloitte’s forecasted baseline. Our forecast, therefore, includes four different scenarios to illustrate possible future paths of the US economy. Deloitte’s forecasting team places subjective probabilities on each of the four potential scenarios.

The baseline (55 percent probability): Weak foreign demand weighs on growth. US domestic demand is strong enough to provide employment for workers returning to the labor force for a couple of years, and the unemployment rate remains about 5 percent. GDP annual growth hits a maximum of 2.5 percent. In the medium term, low productivity growth puts a ceiling on the economy, and by 2019 US GDP growth is below 2 percent, despite the fact that the labor market is at full employment. Inflation remains subdued.

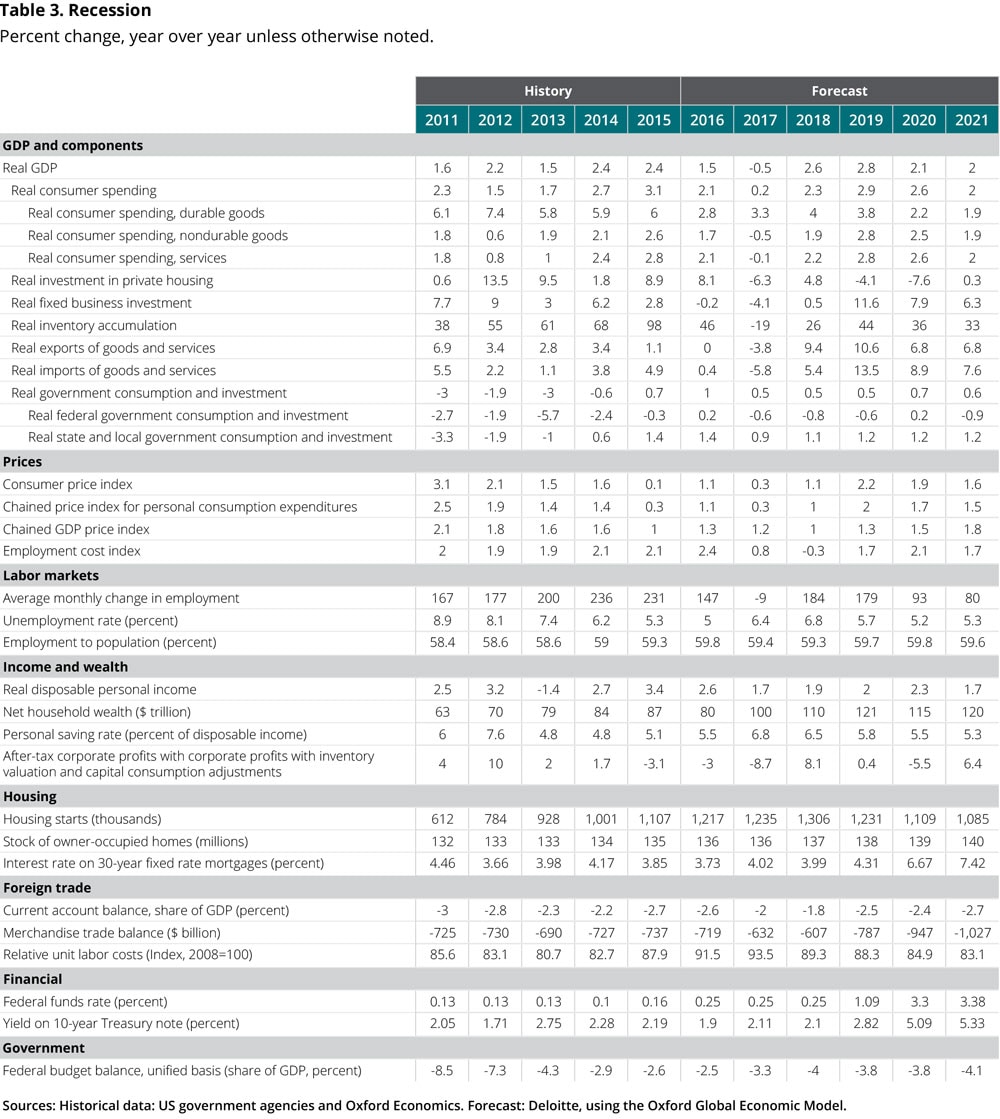

Recession (5 percent): China’s financial problems create a drag on its economy, and growth slows substantially. This triggers a financial panic in East Asia, as investors in countries connected by supply chains to China seek to reduce risk. Volatility in Europe increases, as does market valuation of the riskiness of euro assets, adding to the panic. Several US financial institutions find themselves long on euro- and China-related assets at the wrong time. The result: a global financial panic. Capital flows into the United States to avoid risk in Europe and Asia, and the US dollar climbs even higher. The financial panic throws the US economy into recession. Timely Fed action offsets the financial crisis after several months, leading to relatively fast growth during the recovery.

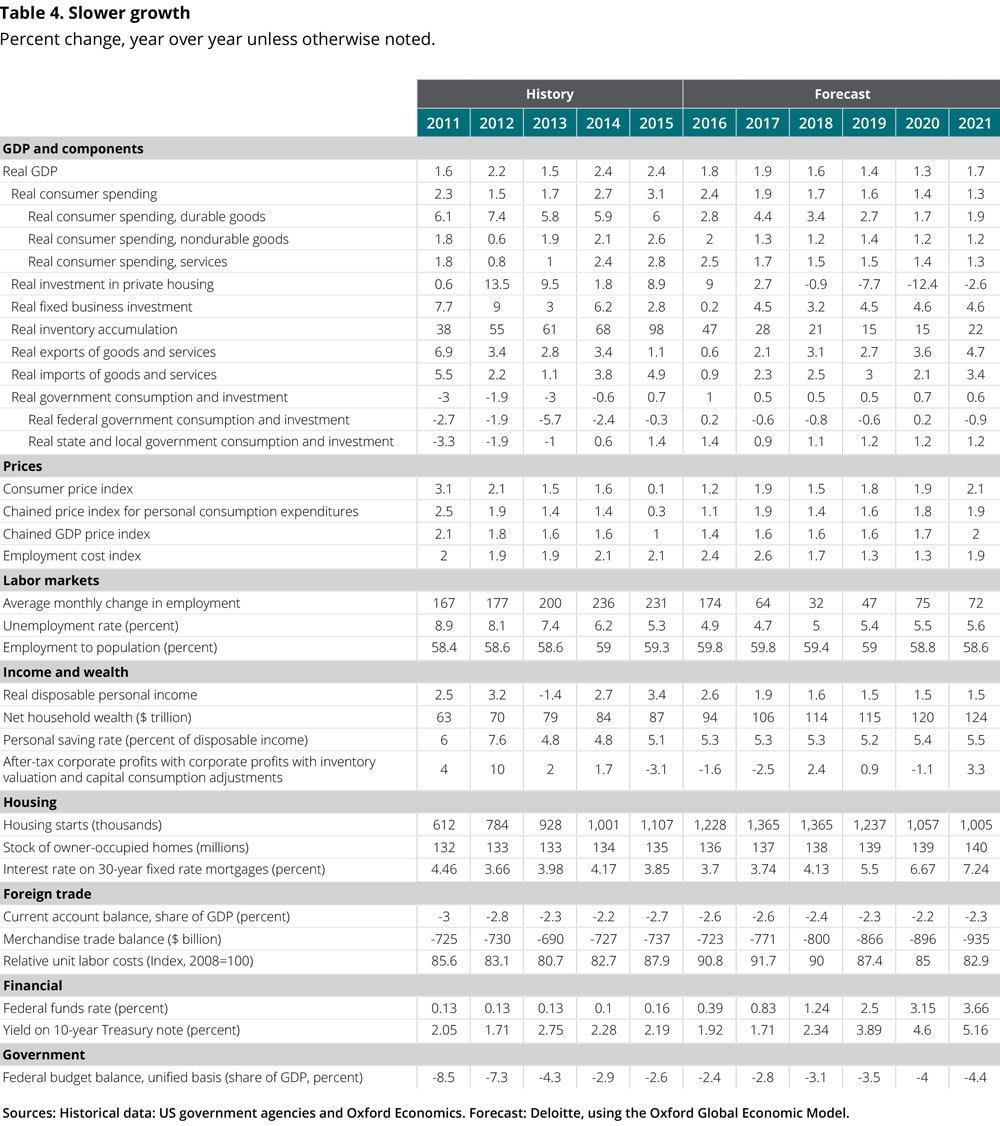

Slower growth (25 percent): Weak economic conditions abroad, financial turmoil, and flight from risky assets cuts demand below the level required for labor market equilibrium. Although the participation rate climbs slightly, hoped-for jobs disappear and the unemployment rate rises. Despite that increase, the Fed slowly raises interest rates, helping to keep a cap on inflation. GDP growth stays below 2 percent for the foreseeable future.

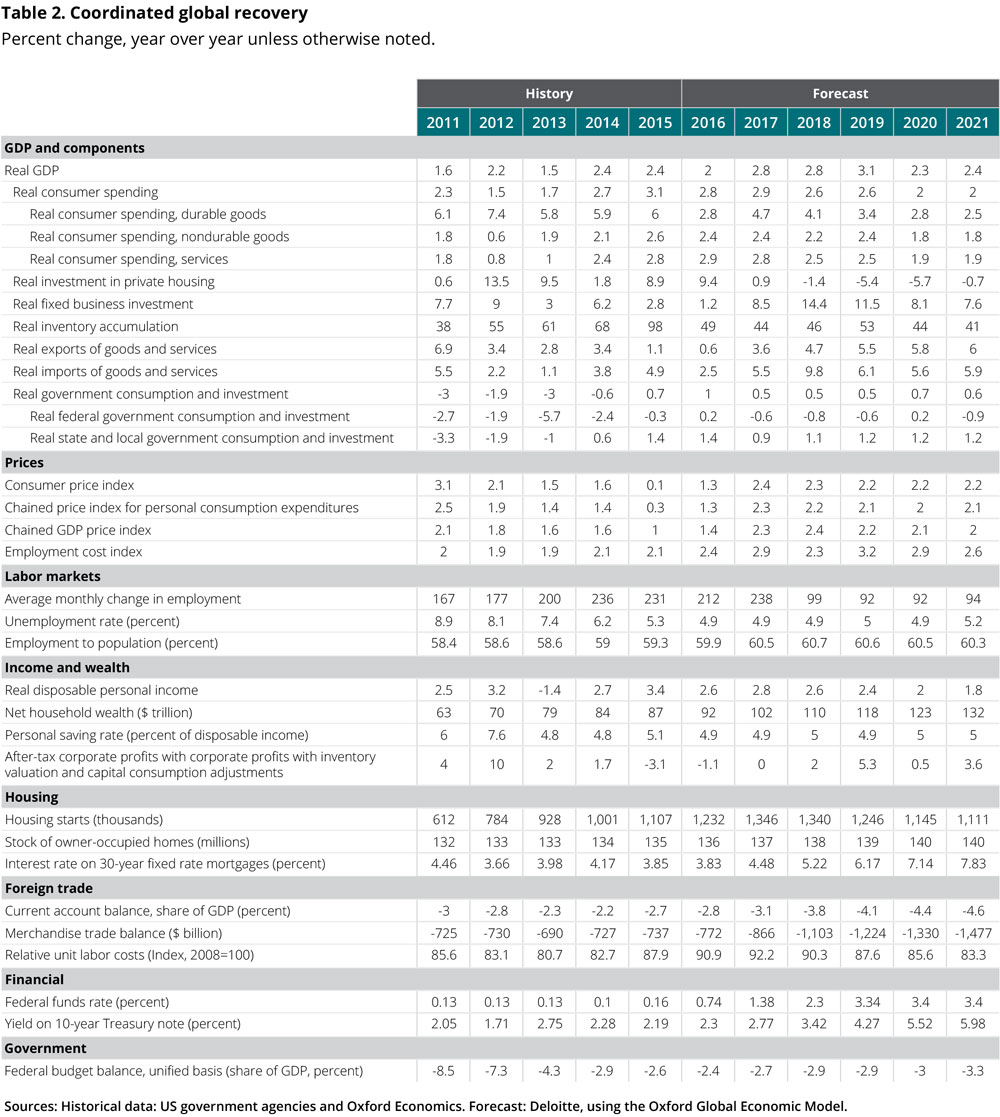

Coordinated global boom (15 percent): Terrorism and refugee problems prove to be only minor obstacles for European economies, and the continent finally begins to pull out of the doldrums. Emerging markets also pick up momentum as China resolves its financial problems, and India and Brazil start to adopt more reforms. Capital flows out of the United States and into Europe and the developing world, pushing the dollar lower, further enhancing US exports. Lower US energy prices make the United States even more competitive. At home, the resolution of budget issues at both the federal and state levels allows more money to flow into infrastructure investment, creating short-term demand and long-term productivity growth.

Sectors

Consumers

Ah, the US consumer—longtime supporter of the global economy, and still surprisingly resilient. Of course, consumers can’t spend money they don’t have, and their incomes largely depend on having jobs. Job growth has picked up, with wages showing faint signs of rising too. Despite that, higher saving rates mean that US consumers have started sending a message to the rest of the world: They cannot continue to play Atlas, holding the global economy on their shoulders as they did in the 2000s. Our forecast expects the US savings rate to settle in at just over 5 percent; that is consistent with consumers’ behavior in the 1990s.

US households face some obstacles in their pursuit of the good life. They have (mostly) recovered from the overborrowing of the 2000s, though too many remain “underwater,” with houses worth less than what the household owes on the attached mortgage. And there is the problem of growing income and wealth inequality. (For a brief inequality discussion, see Ira Kalish’s Deloitte Review article “Mind the gap.”2 ) Recent presidential debates—and the commentary around them, addressing working-class concerns and fears—suggest that inequality will be a focus of policy in the future.

Many US consumers spent the 1990s and ’00s trying to maintain spending even as incomes stagnated. After all, excitable pundits kept assuring them that the technology transforming their lives would soon—any day now—make them all wealthy. But now they are wiser (and older, which is another problem, as many Baby Boomers face imminent retirement with inadequate savings). As long as a large share of the gains from technology and other economic improvements flows to a relatively small number of households, overall US consumer spending is likely to remain relatively restrained.

Consumer news

Real consumer expenditures rose just 0.1 percent on average in the first three months of 2016 but then jumped 0.6 percent in April. As incomes continued to rise at a satisfactory rate, the saving rate was up to 5.9 percent by March before falling back to 5.4 percent in April.

Headline retail sales were slow until April, when a sudden and unexpected jump in April (1.3 percent, 0.8 percent less motor vehicles and parts) indicated that the slowdown was likely temporary. Higher gasoline prices are responsible for part of the increase, but sales rose in almost all categories.

Consumer confidence has fallen slightly off the end-of-year highs but generally remains elevated. Continued strong job growth and some stirrings of wage gains are likely keeping consumers buoyant.

Housing

Every year, thousands of young Americans abandon the nest, happy to leave home and start their own households. But more than usual stayed put during the recession: The number of households didn’t grow nearly enough to account for all the newly minted young adults. We expect those young adults would prefer to live on their own and create new households; as the economy recovers, they will likely do exactly that—as previous generations have.

This likely means some positive fundamentals for housing construction in the short run. Since 2008, the United States has been building fewer new housing units than the population would normally require; in fact, housing construction was hit so hard that the oversupply turned into an undersupply. But the hole isn’t as large as you might think. Several factors offset each other:

- If household size returns to mid-2000s levels, we would need an additional 3.2 million units.

- On the other hand, household vacancy rates are much higher than normal. Vacancy returning to normal would make available an additional 2.5 million units—which would fill 78 percent of the pent-up demand for housing units.

- But are the existing vacant houses in the right place or condition, or are they the right type, for that pent-up demand? The future of housing may look very different than in the past. Growth in new housing construction has been concentrated in multifamily units. If that continues, we may find it is related to young buyers’ growing reluctance to settle in existing single-family units.

In developing our housing forecast, we assumed that the demand for housing (in the form of the average household’s size decreasing) picks up in 2016, vacancy rates gradually drop, and household depreciation begins falling after new renters and buyers remove about 2.5 million housing units from the nation’s housing surplus. Slowing population growth suggests that we will have a short-lived housing boom in which starts hit the 1.3–1.4 million level, followed by a period of contraction until starts reach the level of long-run demand. We estimate this to be about 1.0 million units in the medium term. Housing will likely contribute to GDP growth in 2016 but subtract from GDP growth by 2018 as the pent-up demand goes away. In the long run, the slowing population suggests that housing will not be a growth sector (although specific segments, such as housing for elderly residents, might well be very strong).3

Tight housing credit may be a key culprit in keeping individual purchases of single-family houses low, although there are some signs that credit is loosening. Young adults also seem to be showing a preference for living in urban rather than suburban communities. There may be some significant changes from the post–World War II model of single-family home ownership in store.

Housing news

Housing permits fell in the first few months of 2016, although April saw a significant rebound. Much of the decline was in the volatile multifamily segment; single-family permits remain stable, although at a low number compared to the pre-recession period. Housing construction remains substantially below the level needed to meet the pent-up demand for housing created by the lack of construction since 2008.

Contract interest rates have fallen about 30 basis points in the past six months. House prices are rising very slowly—as of February, the Case-Shiller home price index was about 5 percent above the year-ago level.

Business investment

Since the recession’s end, many have lamented the impact of political uncertainty on business decisions—specifically, on investment. In fact, relative to GDP, business investment has been one of this recovery’s better-performing sectors. With strong profit growth, however, businesses might well have invested even more. Many businesses are likely still waiting for assurance that they will have customers; once those customers return, there may be more reason to ramp up investment. Watch what businesses do, not what they say.

Other, more concrete factors are also weighing down investment. The rising dollar is not only making US companies less competitive—it’s cutting overseas earnings valued in dollars and therefore reducing margins for US multinationals. And China’s slowing growth is exposing global excess capacity in many industries. In our baseline scenario, these factors help to moderate growth and demand. In the “slower growth” scenario, they become important factors in keeping the US economy below potential growth.

The fall in oil prices is a complicating factor in this positive outlook. Oil and gas extraction accounted for 6 percent of all nonresidential fixed investment in 2013. That’s a hefty amount (considerably larger than the sector’s value-added share), so shutting down new US oil exploration will have an immediate impact on investment. However, the big drop in the price of oil will surely eventually affect the 94 percent of business investment that is unrelated to oil and gas extraction.

Business investment news

Real business fixed investment fell at a 5.6 percent annual rate in the first quarter (according to the first GDP release), the second consecutive quarter of decline. Both equipment investment and structures investment fell, while intellectualproperty investment rose a subpar 1.7 percent.

Nondefense capital-goods shipments—an effective high-frequency measure of equipment spending—was flat over the first three months of the year. That’s an improvement over the end of 2015. The less-volatile category of capital goods less aircraft, however, fell in January and February and was flat in March.

Private nonresidential construction grew in the first three months of 2016. Office construction was particularly strong (growing at an average monthly rate of over 3 percent). Commercial and manufacturing construction grew more slowly.

The cost of capital remains very low. Interest rates fell from 4.0 percent for AAA corporate bonds at the end of 2015 to just 3.6 percent by April 2016. Stock indexes picked up after February. Profits remain at near record levels of national income.

Foreign trade

Globally, the United States should be highly competitive. US unit labor costs have been falling and remain low despite the slowdown in productivity (as wages are stagnant, by and large). In a smoothly running global economy, the need for capital in the developing world should help to keep the dollar at a reasonable level, and the international price of US goods would be very attractive.

The global economy, alas, is not functioning well. The high US dollar has more than offset falling American unit labor costs, as global investors seek security in US assets. And weak demand abroad tends to make the job of American exporters even harder.

All of this amounts to a substantial headwind to US GDP growth. Our baseline forecast shows real export growth of around 2 percent for 2016 and 2017, picking up to 5–6 percent afterward. The current account starts falling relative to GDP in 2018 but remains over 2 percent for the entire forecast. Until growth in Europe picks up, it is hard to see trade contributing to US GDP growth.

Foreign trade news

US goods rose substantially in April after falling in March. This may indicate that the decline in exports that began in late 2014 is reaching its bottom. Overall imports rose in April but made up less than half the ground lost in March. The overall trade balance was slightly lower in April and March than it was in November–February.

The dollar has been falling against most major currencies, with a rise in the euro since February as the exception. At $1.13 (as of early June), the euro is still quite cheap. European GDP growth has been surprisingly strong, although industrial production remains weak.

The Chinese economy is recording satisfactory growth, though many observers remain concerned about the country’s financial system and continuing infrastructure investment. Some analysts focus on signs of strength in China’s consumer and service sectors, suggesting a long-awaited adjustment to becoming a consumer-driven economy. Others point to indications that official Chinese figures may be implausibly high. China’s future remains a large risk for the global economy.

Government

US government spending on goods and services has been stagnant, and we expect little change in the next few years. That’s actually an improvement from the 2010–13 period, when government cutbacks pulled down economic growth. In 2016, we are actually seeing a modest contribution of federal spending to GDP. That’s the result of the last federal budget agreement, which raised caps on both defense and nondefense purchases.

However, pressures from entitlement spending are expected to keep the lid on future increases in federal government demand.

Congress, though, is far behind schedule on appropriations for the next fiscal year. There may be a small prospect of yet another budget crisis, this one in the middle of the presidential election campaign. Our baseline forecast assumes that cool heads will prevail and the federal government will remain funded through the end of the forecast horizon.

After years of belt-tightening, most state and local governments are no longer actively cutting spending. They are getting some good revenue news from rising house prices and growing employment, though low oil prices continue to weigh on the budgets of several states with large oil-production sectors, and pesky pension liabilities continue to restrain state and local spending, The Congressional Budget Office estimates a shortfall of $2–3 trillion in state and local pension funding, and the need to fund these liabilities will likely keep a lid on state and local spending growth.

Government news

The federal deficit was about 25 percent higher in the first seven months of FY2016 than in the same period in FY2015. Outlays were up 4.4 percent, while revenues rose only 1.2 percent. Federal tax collections in April 2016 were lower than expected, reflecting lower final payments for 2015 individual income taxes than authorities expected.

Government employment at all levels has been essentially flat over the past few months.

Labor markets

If the US economy is to produce more goods and services, it will likely need more workers, and the currently moderate wage growth is encouraging firms to increase capacity by hiring workers. However, many potential workers remain out of the labor force: They left in 2009, when the labor market was terrible, and conditions apparently are still not good enough to entice them to return. Accelerating production will carry with it an eventual acceleration in demand for workers, along with a welcome mild rise in wages. That should help to bring people back into the labor force.

But a great many people have been out of work for a long time—long enough that their basic work skills may be eroding. When the labor market tightens, will those people be employable? Deloitte’s forecast team remains optimistic that improvements in the labor market will eventually prove attractive to potential workers, and labor force participation will pick up accordingly.

Deloitte labor force projections

In the near term, the overall participation rate will likely be affected by two offsetting trends. The aging of the population—in particular, early Baby Boom cohorts reaching retirement age in the next five years—will push down the participation rate. However, the poor labor market has driven down participation rates for younger workers as well, and the economic improvement in the forecast will almost certainly entice many people in these middle-aged and, especially, younger cohorts to return to the labor market.

The labor force projection in this forecast assumes that participation rates for the over-60s will remain at current levels and that participation rates for the under-30s will return to their 1997–2000 average.4

Labor market news

Monthly initial claims for unemployment insurance are holding steady, in the 260,000 range. Job openings continue to grow and, at almost 5.8 million, are at the highest level recorded in this data. Quits (voluntary separations) fell in January, possibly because of seasonal reasons, but have resumed rising. The high level of voluntary quits suggests that labor demand remains strong.

Payroll employment growth dipped in April and came in very low in May, bringing the three-month average to just 116,000. The unemployment rate fell to 4.7 percent, but that’s because the participation rate has been falling; it remains considerably lower than the average rate before the financial crisis, even adjusted for the age of the population. The forecast assumes this is within the normal variation of a growing economy.

Financial markets

Interest rates are among the most difficult economic variables to forecast because movements depend on news—and if we knew it ahead of time, it wouldn’t be news. The Deloitte interest-rate forecast is designed to show a path for interest rates consistent with the forecast for the real economy. But the potential risk for different interest-rate movements is higher here than in other parts of our forecast.

Global financial markets are now in a highly unusual state. About $10 trillion in sovereign debt is now trading at negative interest rates (meaning borrowers are paying for the privilege of loaning money to these countries).5 The existence of negative interest rates is unprecedented, and the fact that even large countries (such as Germany) are borrowing on these terms indicates that global financial markets have not fully recovered from the problems of the previous decade.

Despite this, the forecast sees both long- and short-term interest rates headed up—maybe not this week, or this month, but sometime in the future. The economy’s return to full employment would mean a return to “normal” short-term interest rates, though relatively slow growth will likely keep a lid on longer rates in the medium term. The 10-year bond rate is set to rise but will likely remain at relatively low levels throughout the forecast period.

But the most sophisticated observers of financial markets understand the most important thing about interest rates: They fluctuate. This is the sector that is most likely to surprise us.

The current baseline assumes that the Fed will raise interest rates once—in July—during the remainder of the year. While speculation on the precise date of the next Fed hike has fluctuated with economic data—particularly with the monthly employment report—the overall forecast would not significantly differ if the Fed hiked earlier or later, and raised rates two or three times instead of the assumed one time. The anticipated impact of each hike is relatively small (although the cumulative impact may be large). And the exact timing is much less important for the economy than the overall trend and direction of rate changes.

Financial market news

Although the Fed left interest rates unchanged in April, minutes from the Open Market Committee meeting suggested that members might be comfortable with a summer hike. The most recent “dot plots” suggest that the Fed will hike interest rates twice this year.

Risk spreads jumped in early 2016. By February, the junk-bond spread over AAA bonds was 4.4 percentage points. Since then, risk spreads have fallen as the stock market has picked up.

Stock prices rose in March, fell in April, and rebounded somewhat in May, making up most of the ground lost in the December–February stock market correction.

Bank lending remained healthy, with loans growing at an average rate of over 9 percent since the beginning of 2016.

Prices

Remember the pundits who proclaimed loudly that the Fed’s actions in 2009 would spark run away inflation? Likely, they’d rather you didn’t. Prices have been the most boring part of forecasting for the past six years, and there is little reason to think that’s going to change.

Inflation is hard to come by when the labor market—which accounts for two-thirds of all costs in the US economy—has been so slack. Workers haven’t had leverage to obtain higher wages when prices go up, and businesses generally lack the pricing power to cover higher costs. Instead, shocks from higher (or lower) energy or food prices have dissipated into the ether rather than being translated into sustained, higher inflation.

That means that inflation will likely remain tame at least until the economy reaches full employment. Although employment growth in the past couple of years has whittled away at the potential employment surplus, it’s still pretty large—and bigger than the unemployment rate indicates. So don’t hold your breath waiting for the return of the 1970s. Bell bottoms, disco, and high inflation are likely all safely in our past (for now).

Price news

Overall CPI growth remains low (1.1 percent over the past year in April), although much of that is due to falling gasoline prices. Core CPI was up 2.1 percent in April, slightly less than earlier in the year. Rising gas prices will push up the overall CPI in the next few months.

Final demand PPI is almost flat for the year; this is partially because of energy, but the core PPI is up just 0.9 percent, so there are few “pipeline” inflationary pressures.

Wages remain relatively tame. Average hourly earnings grew 2.5 percent over the past year, about the same as in the recent past. This is still below the 3.0 percent average growth rate recorded during the previous recovery.

Appendix: Deloitte economic forecast

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.