Beyond the acute episode has been saved

Beyond the acute episode Can retail clinics create value in chronic care?

14 October 2016

Retail health care clinics got their start by providing convenient access to acute care services. Now, new payment models are setting the stage for retail clinics to become a meaningful player in chronic care delivery as well.

Executive summary

Although retail clinics have been offering some chronic care services since 2013, they have yet to achieve a notable footprint in this space. Now, new payment models are creating the business case for health systems and retail clinics to partner to add more chronic care services to clinics’ limited menu. This can be a positive development, as retail clinics have the potential to improve chronic care by increasing access to care, boosting patient engagement, lowering cost, and improving outcomes. Our view is that, with changing payment models, the time has come for retailers to become a meaningful player in chronic condition management.

Chronic disease facts

- Eighty-six percent of all health care spending in 2010 was for people with chronic conditions.1

- The seven most common chronic diseases account for nearly two-thirds of all deaths.2

- Between 20 and 29 percent of the cost for chronic diseases is spent on treating potentially avoidable complications.3

- Nonadherence carries a high cost among patients with multiple chronic conditions: $2,000 to $8,000 per patient per year.4

Retailers’ success at chronic care management calls for strong collaboration with health systems. To date, fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement has mostly discouraged such collaboration, since under FFS, retail clinics would pose a competitive threat for lost revenue to both physicians and health systems. And retailers, who depend on physicians for pharmacy scripts, have been careful not to be viewed as competitors. However, the landscape is changing. While many health systems and medical groups still make most of their revenue under FFS,5 the Medicare Access & CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) should accelerate the shift to value-based payment models. This shift may encourage partnerships between health systems and retailers around chronic care delivery, as incentives under value-based payment models reward physicians for delivering care more cost-effectively and for having high quality-of-care scores. Under these incentives, retail clinics, with their ease of access, protocol-driven processes, and low cost structure, can become attractive partners for health care providers.

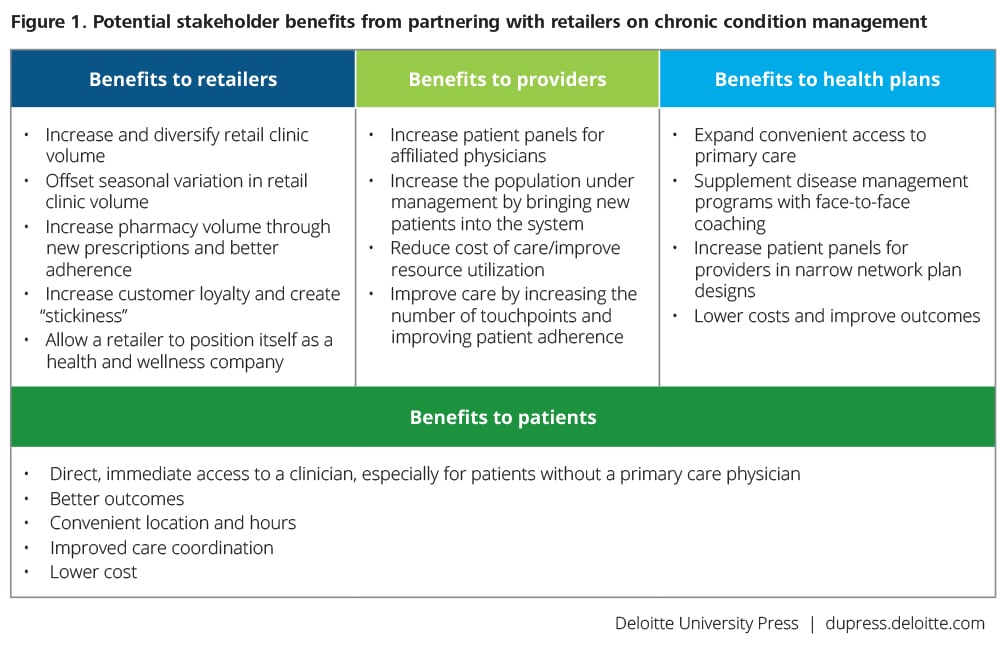

Through interviews with industry executives and an extensive literature review, we sought to understand what role retail clinics can play in chronic care and how they can meet the needs of the health care system. Although still in their early days, partnerships with retail clinics around chronic care services can offer important benefits to retailers, health systems, patients, and health plans.

Introduction

Even though many physicians initially resisted retail clinics as primary care providers for minor acute ailments, today retail clinics are largely accepted. Concerns that retail clinics would lower the quality of care and disrupt the patient-physician relationship were not borne out. Research has shown that the quality of care delivered by clinics for the most commonly treated conditions is on a par with the care delivered by physician offices. Further, about 60 percent of retail clinic customers do not have a primary care physician (PCP), so there is no patient-physician relationship to disrupt.6

While retail clinics have won many customers due to their convenience, the business model has proven challenging. For one thing, margins are thin. Furthermore, retail clinics must compete on the revenue-per-square-foot metric against high-margin categories such as health and beauty, alcohol, and automotive.7 For a retail clinic to be profitable, each clinician must see as many as 30 patients per day.8

Over time—to offset seasonal fluctuations in volume—retail clinics have added many nonacute care services. Among these are camp and sports physicals, smoking cessation services, biometric screenings, and blood glucose testing and monitoring.9 Retailers’ official entry into chronic care came in 2013, when a major retail clinic operator announced it was expanding its services to include diagnosis and treatment of select chronic conditions.10 Other retailers have followed suit. Yet the uptake of retailers’ chronic care service offerings has been slow.

The Deloitte 2015 Survey of US Health Care Consumers found that only 11 percent of retail clinic users had visited a retail clinic for management of a chronic condition. That said, overall interest in doing so was fairly high: 68 percent of consumers with chronic conditions were interested in using retail for chronic care. Among those who were reluctant to use retail clinics, the main reasons were the desire for an ongoing relationship with a physician, doubts about the quality of care at a retail clinic, and a preference to receive all care in the same place so that clinical information could be kept in one place or system.11

About this research

To inform the views expressed in this report, we interviewed 19 individuals from 17 organizations, including retail clinic operators, urgent care centers, health plans, integrated health systems, and academic medical centers. Respondents included vice president, C-suite, and director-level executives in pharmacy, networks, clinical affairs, marketing, and strategy, as well as a nationally prominent health services researcher. Our research also included a thorough review of trade journals, the business press, and peer-reviewed literature.

Success in chronic condition management calls for close partnerships

New payment models to bring about change

Some objections to the concept of delivering chronic care in a retail setting echo those voiced in the past: It will increase care fragmentation and clinic staff will not be able to care for patients with complex issues. While these are valid concerns, however, retail clinics can likely address them through collaboration with health systems, which can deliver benefits to both parties. Retailers could benefit from increased pharmacy volume, foot traffic, and becoming a health and wellness destination, which can help them build customer loyalty. For their part, health care providers could improve access to care for their existing patients, increase the size of their patient base, lower costs, and improve care quality for patients with chronic health conditions. For health systems with academic medical centers at their core and sparse primary care capabilities, partnerships with retail clinics may be especially beneficial as a way to build up their capacity around basic primary care, minor acute care, and chronic disease management.

In partnerships with health systems, retail clinics could act as an extension of primary care, not as a replacement for it. The clinics could serve as additional care access points beyond the traditional doctor’s office or hospital. This is especially relevant in areas experiencing physician shortages,12 which are expected to become worse as the US population ages and the need for health care services increases. While today, being an extension of primary care largely involves providing minor acute care and flu shots, the pressure to lower costs created by value-based payment models could encourage traditional health care providers to tap into retail clinics for chronic care delivery as well.

Few health care organizations have direct experience operating retail clinics

A few integrated health systems with a long tradition of a population health focus have a strong track record of running community primary care centers and employer worksite clinics.13 The majority of health systems, however, have historically been hospital-centric. Due to their inpatient focus, hospital-centric organizations might not have the expertise around workflow design of outpatient retail-like operations around primary care. Therefore, for these organizations it may make better business sense to partner than to develop this expertise in-house.14

Other convenient care providers—urgent care and telemedicine—do not offer as compelling of a value proposition as retail clinics for supporting health systems in chronic condition management. While urgent care centers offer similar patient convenience in terms of locations and operating hours, their cost structure and workflow are much less conducive to the provision of chronic care services.15 Telemedicine has great potential to improve chronic care as an enabling technology if it can be incorporated into providers’ existing workflows. However, the case for using direct-to-consumer telemedicine providers to deliver chronic care services is less compelling: Absent a preexisting relationship and face-to-face interaction, using telemedicine providers for chronic care would offer no more benefits than telephonic disease management programs, whose cost-effectiveness has been disappointing.16

The rarity of mature provider-retail partnerships today may reflect the disincentives to collaborate under current FFS reimbursement models, since under FFS, retail clinics can pose a competitive threat to both physicians and health systems. Now, however, the movement toward value-based payment models is creating pressures of a different kind that favor rather than discourage collaboration. Under value-based models, competitive concerns are no longer in play, as physicians are rewarded for delivering care in the most cost-effective manner. Indeed, many of the industry executives we interviewed observed that providers who have embraced value-based care are much more open to partnering with retail clinics. Said one: “Physician groups that are at risk are more inclined to partner with outside organizations, such as retail clinics. Physicians in FFS find such partnerships more competitive and less valuable.”

The recent enactment of MACRA should accelerate the transition to value-based payment models and encourage health systems to seek out clinical partnerships that help improve cost and quality. Beginning in 2019, clinicians—including physicians, nurse practitioners, and all other clinicians eligible to bill Medicare—will be paid based on MACRA requirements, which will encourage them to focus on managing the total cost of care and on performing well on care quality measures.17 Retail clinics—with their ease of access, protocol-driven processes, and low cost structure—will likely become increasingly attractive as partners for delivering chronic care services.

Understanding MACRA

MACRA outlines two tracks for physician reimbursement from Medicare: advanced alternative payment models and the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System.

What is population health?

Population health involves health care activities that aim to use health care resources effectively and efficiently to improve the lifetime health and wellbeing of a specific population.18

Advanced alternative payment models (APMs)

The case for working with retail clinics will likely be strongest for health systems and clinicians participating in APMs that focus on population health. Under MACRA, clinicians participating in advanced APMs will receive a 5 percent increase to their payments from Medicare. This 5 percent increase would be in addition to any potential shared savings or performance bonuses that APMs may qualify for. On average, Medicare payments account for almost a third of physician practice revenue, and for some specialists (for example, geriatricians or cardiologists), they represent the majority of revenue.19

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed that a number of its existing payment initiatives would meet the definition of an advanced APM. Although the details of the different models vary, they largely fall into three categories: accountable care organizations, comprehensive primary care plus, and bundling.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs). ACOs, led by health systems or physician groups, focus on the total cost of care (not including outpatient drugs) for an assigned population of Medicare beneficiaries. If they meet quality standards and save money relative to a spending benchmark, they can share the savings with Medicare. Examples of quality measures include:

- Patient experience of care, as measured by the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey21

- Preventive care measures, such as rates of pneumonia vaccination for older adults or screening and follow-up for high blood pressure

- Population health measures, such as the rate of hospital readmission, hypertension control, and medication adherence22

If an ACO meets a quality goal, such as lower hospital readmission rates or improved patient experience scores, it receives bonus payments from Medicare (or its health insurance partner, in the case of commercial ACOs). When an ACO lowers spending beyond a predetermined amount, it can receive a portion of the savings as well. If, however, an ACO fails to meet quality and cost goals, it may have to return a portion of the payments to Medicare (or to a private health plan).

With these incentives in place for lowering the cost of care, ACOs may find retail clinics attractive partners. Savings could be material, for instance, if some $200 office visits could be replaced with $79 retail clinic visits, inclusive of lab fees. More generally, retail clinics could help health care organizations improve performance on quality measures and reduce the total cost of care by substituting more expensive services with less expensive ones, improving treatment adherence, or providing targeted primary care services that reduce the likelihood of using hospital or other inpatient care.

Comprehensive primary care plus (CPC+). This model is intended to strengthen primary care practices by encouraging them to provide a broader range of services and make investments that improve patient care. Available in select states, the CPC+ model requires a partnership between Medicare and health plans in which both parties agree to align program elements.

Retail clinics probably would not qualify as primary care practices given their limited scope of services. However, physician practices participating in a CPC+ program may see value in partnering with retail clinics. For instance, a partnership with retail may help practices meet requirements around “access and continuity” of care that include “expanded hours in early mornings, evenings, and weekends”23 without having to extend their own office hours.

Bundling. Bundled payment models generally focus on a set of services over a predetermined period of time, typically following a hospitalization or defined by a health condition like end-stage renal disease or cancer. Organizations paid under the bundle are able to share savings with Medicare if they meet quality goals and reduce spending for services covered by the bundle.

Retail clinics are less likely to have a clear value proposition vis-à-vis the bundled payment initiative, as the services in a bundle tend to be specialized and there is much less focus on primary care than in the ACO or CPC+ models.

In addition to sharing in the gains, clinicians and organizations participating in an advanced APM must share in potential losses by meeting several risk-sharing requirements. See Deloitte’s policy brief MACRA: Disrupting the health care system at every level for details.20

Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)

Retail clinics may also be attractive partners for participants in Medicare’s MIPS track, which rewards lower resource utilization and better quality—metrics that retail clinics may be able to help improve.

MIPS is a pay-for-performance program that varies payment rates to clinicians based not only on what services were provided, but also on that clinician’s past performance on four sets of measures. These measures cover quality, resource utilization, meaningful use of electronic health records, and practice improvement activities. All clinicians, including nurse practitioners billing from retail clinics, will need to report these metrics to CMS in order to avoid penalties. CMS will calculate resource utilization measures reflecting referrals and practice patterns; performance on these measures would affect payments to primary clinicians determined to have provided the most services based on patient attribution criteria.

Payments to nurse practitioners billing services from retail clinics to Medicare will be affected by MIPS if the nurse practitioners are not part of advanced APMs. Other clinicians wanting to do well under MIPS may wish to refer patients to retail clinics if doing so would improve resource utilization measures or help achieve quality goals.

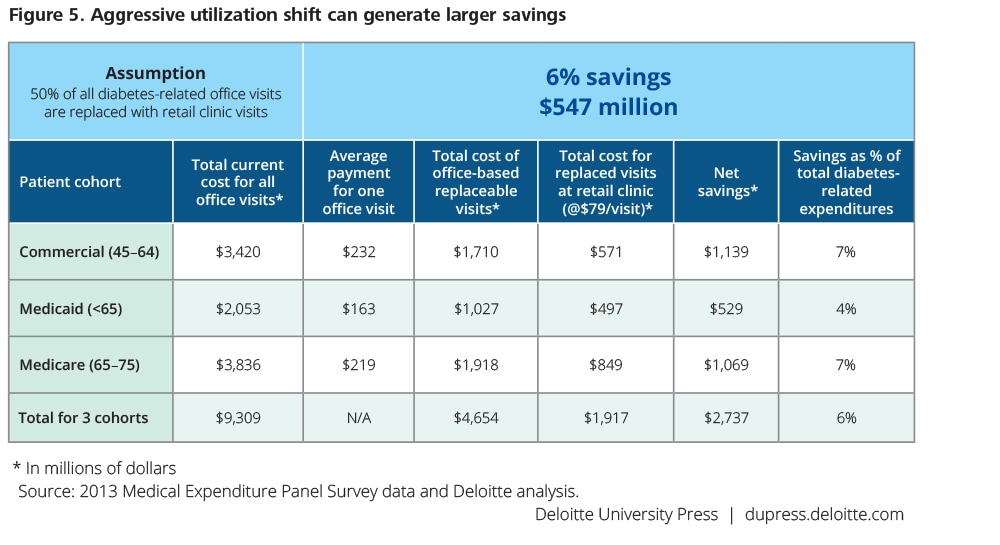

Estimating savings in diabetes-related care

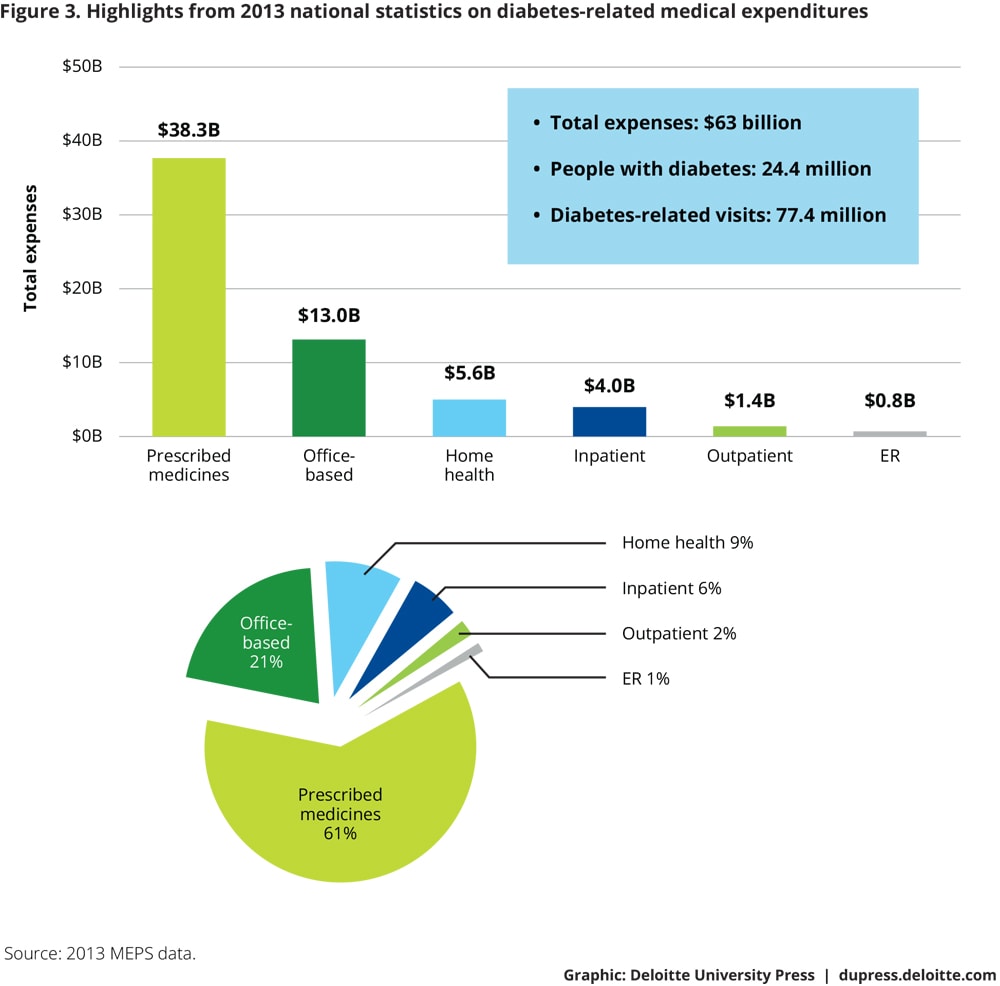

As an illustrative example, we estimated annual medical spending associated with diabetes today and how that spending might change if diabetes-related services became widely available at retail clinics.24

Simple replacement of a patient’s office visits with retail clinic visits could generate a range of savings, depending on the volume of visits being replaced. With retail clinics’ low per-visit cost ($79) compared to the cost of a physician office visit ($160–$230), the total savings across all diabetes patients covered by commercial, Medicare, or Medicaid insurance could total over $100 million ($7 per person per year) under conservative assumptions and as high as $2.7 billion ($164 per person per year) if half of diabetes-related office visits migrated to retail clinics. This difference in fees could benefit physicians under APMs or MIPS if their attributed patients receive care in retail clinics.

If the use of retail clinics increases a patient’s total number of visits (as opposed to simply replacing current office visits with retail clinic visits), the effect on total cost of care could be neutral, but performance on quality measures—such as controlling A1c level, controlling serum cholesterol level, and controlling high blood pressure—is likely to improve. (For more detail on this analysis, please see the appendix.) The long-term savings of more-frequent patient visits, which can lead to improved diabetes control, may be substantial. Studies that take the long-term effects of better diabetes control into account project savings opportunities of up to $1,200 per person per year in commercial populations and up to $1,900 per person per year in Medicare populations.25 Improving care for patients with multiple chronic conditions can have an even higher return on investment, from $2,000 to $8,000 per person per year.26

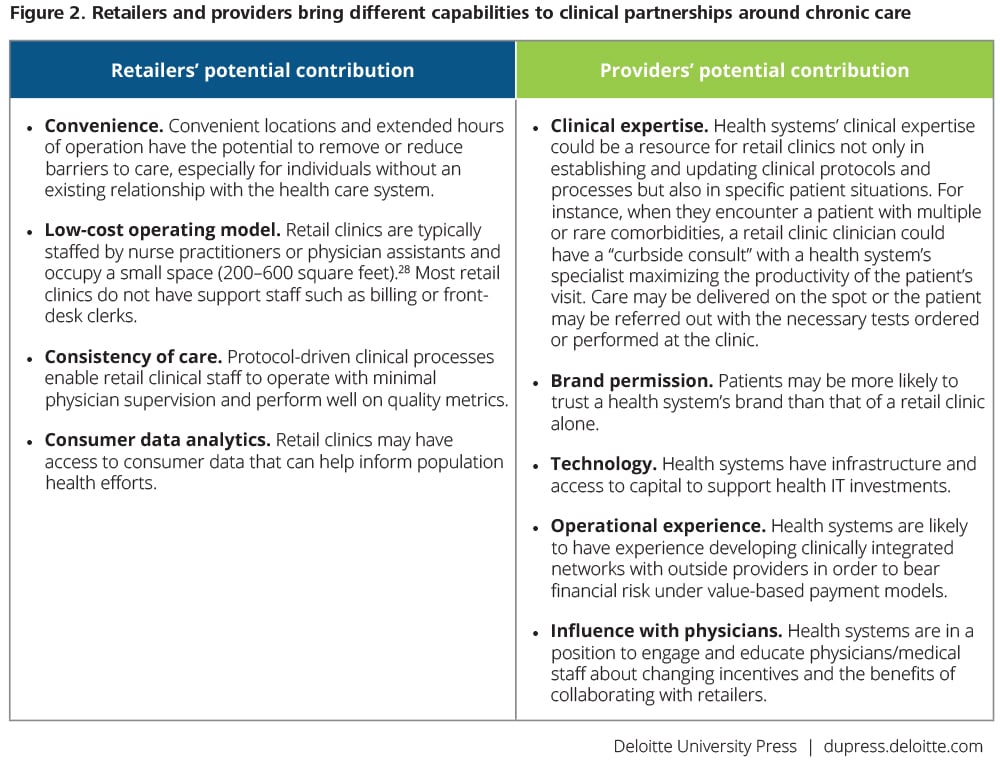

The retail clinic’s role

As a partner, retailers bring many strengths to the table that could be valuable to health care providers: convenience and accessibility for the customer; expertise in protocol-driven processes; experience working in a high-volume, low-price environment; extensive customer analytics; and the potential to apply all these capabilities to improve patient engagement, treatment adherence, and ultimately health outcomes. With proper precautions in matters of privacy and security, retailers could conceivably use their expertise in collecting, analyzing, and leveraging consumer data to influence consumer behavior. For instance, buying patterns could trigger invitations for some shoppers to visit the clinic for a health screening. Many retailers also have expertise in digital and consumer engagement through social media, and could use these skills to help health system partners to engage more meaningfully with prospective and existing patients.

Retailers know that this person buys full-sugar soda and Twinkies, and that they also have a 35-pound poodle. This kind of epidemiological data would be a gold mine for population health. But we haven’t found a way to use it.—Health plan chief medical officer

As retail clinics take a bigger role in chronic care management, they may also be well placed to improve patients’ access to medical technology, such as telemedicine and remote monitoring tools. Telemedicine can reduce the need for in-person visits by allowing patients to access care via connected devices—a computer, a smartphone or tablet, or a health kiosk. Further, much routine measurement, tracking, and analysis (such as blood pressure or blood glucose measurement) may become automated through the remote use of smart devices, such as web-enabled blood pressure cuffs or continuous glucose monitors. While the technology may change the format of some provider-patient interactions, other research has shown that many consumers will want to keep a human connection with their regular care provider,27 which very well may be a retail clinic clinician.

Thus, retailers can be in a position to provide hands-on care to those patients who prefer traditional in-person visits, to virtually guide patients’ care as part of a broader care team, and to facilitate physical access to telemedicine technology for those consumers who need help (for instance, through health kiosks or through nurse-facilitated telemedicine visits). In the case of nurse-facilitated visits, telemedicine can help retail clinics expand their scope of services, similar to the way Kaiser’s retail clinics at Target stores do (see sidebar later in this report, “Health system-owned clinics”). This combined approach has the potential to surpass the individual benefits of either a telemedicine or a retail clinic visit: Patients get access to specialized clinical expertise beyond the nurse practitioner’s scope of practice, while at the same time, the nurse practitioner is there to perform the physical exam that a patient may not be able to do on his or her own.

The health system’s role

Health systems also have a great deal to bring to partnerships with retail clinics. Among a health system’s leading strengths in such a partnership are clinical expertise, especially around complex patients and conditions; consumer acceptance of the health system’s brand; and trust in the system’s reputation for chronic and specialty care. Furthermore, health systems have experience with complex IT infrastructure, including the staff to support it, as well as access to capital to maintain and improve their IT investments. Lastly, health systems are in a position to engage physicians around the use of retail clinics; to educate them about the benefits of partnership and help them overcome their misgivings; and to develop the referral relationships that can help manage cost, improve quality, and benefit patients.

We expect retailers’ and health systems’ roles in the partnership to reflect their respective strengths. Retail clinics can provide the facilities; the operational know-how to run a high-traffic, cost-conscious, protocol-driven work environment; and marketing expertise. Health systems can provide clinical leadership, a patient referral network, the strength of their brand, and continuing training and education to physicians and clinical staff.

Pursuing the opportunity: Which conditions, which patients?

Chronic conditions for retailers to target

Pragmatically, in order to make chronic care services economically feasible to deliver, retail clinics would likely wish to focus on conditions that meet three criteria:

- Prevalent conditions. For widespread conditions, expertise can be scalable: A retail clinic operator could develop its expertise in one market and transfer it to others. Retail clinics also have the option of pursuing depth rather than breadth in the treatment of prevalent conditions. For instance, retailers may develop a comprehensive suite of services around one or several related conditions, such as testing and monitoring, health coaching, nutritional counseling, and medication therapy management.

- Conditions that have well-developed clinical guidelines. The existence of clear clinical guidelines enables retail clinics to take full advantage of their low-cost staffing model, as treatment can be standardized and nurse practitioners and physician assistants can deliver care with minimal physician oversight. Some of our research participants point to studies that suggest that midlevel practitioners, such as nurse practitioners, may even be better suited than physicians to deliver routine chronic care.29

- Conditions that have been shown to improve with more-frequent patient interactions. A large part of many retail clinics’ business case to prospective partners can be that their patients/members are regular customers at the store where the clinic is located, and that the retail clinic can therefore effectively engage these patients through frequent face-to-face contact. The effectiveness of many disease management interventions is a function of visit frequency,30 and choosing conditions where evidence supports the link between visit frequency and outcomes would strengthen the case for retailers. The opportunity for face-to-face contact could further strengthen the case, as in-person interventions are known to be more effective than other modalities (telephonic, self-care, online).

Our research participants identified four chronic conditions—high cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes,31 and asthma—as meeting these criteria. They also suggested a few other areas of opportunity, including chronic heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), transitional care (post-hospital discharge), obesity, and even HIV/AIDS in markets with a high concentration of these patients. However, for retail clinics, expertise around these conditions may be either more difficult to acquire or less scalable if operators wish to transfer their chronic care experience to new markets. For all conditions, participants recommended that retailers assess opportunities on a market-by-market basis depending on condition prevalence, physician supply, the structure of the local health care delivery system, and prospective partner readiness for value-based care.

Patients to pursue

Knowing the right patients to target with services would also be very important to the success of provider-retailer partnerships. Targeting those without a primary care provider (PCP) may be quite effective in building retailers’ chronic care business. In the United States, one in four people do not have a PCP; among retail clinic patients, that proportion is as high as 60 percent.32 Granted, current retail clinic users tend to be younger and healthier than the general population or patients who visit a PCP.33 But even in this relatively low-risk group, early diagnosis, the identification of patients at risk of developing chronic illnesses, and the ability to engage individuals with the health care system could benefit everyone involved.

There’s a systemic belief in the United States that a primary care physician is always the right answer. Still, there’s value in having the patient visit someone rather than no one.—Pharmacy benefit management and pharmacy executive

Another target segment could be patients with chronic conditions who experience barriers to care in the traditional care delivery system, preventing them from getting the care they need. One such barrier could be as simple as being too busy: A patient may be unable to see a provider as often as he or she should because school, work, or family obligations prevent him or her from setting aside hours at a time to visit a doctor’s office every few months. Or a mix of cultural and socioeconomic factors could come into play: For example, Latinos are the least likely of all US ethnic groups to visit a doctor due to cultural beliefs, high uninsurance rates, and being in jobs (for many) that make it difficult to take time off from work.34 Retailers, with their convenient locations, cultural awareness, and experience in influencing consumption behavior, may be able to engage these hard-to-reach patients.

Engaging patients with chronic conditions early can have considerable cost-saving potential. An estimated 86 percent of all health care spending is on patients with chronic diseases.35 In commercial patient populations, potentially avoidable complications from six chronic conditions (CHF, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, COPD, and asthma) account for 29 percent of the treatment costs for these conditions.36 From a health plan’s perspective, there is tremendous value in catching patients “who are about to go south,” as one of our interviewees put it.

Realizing savings from improved treatment adherence

Improving treatment adherence can have a high return on investment, particularly among patients with multiple chronic conditions. A recent study has found that, among patients with three or more conditions (such as diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol), the savings associated with becoming treatment-adherent ranged from $2,000 to $5,300, with the highest savings associated with those who had diabetes as their primary condition. When patients became nonadherent, costs increased by $4,000 to $8,000, with the highest increase among patients with hypertension as the primary condition. The study’s authors note that:

- The combined effect of diabetes and hypertension on medical spend is far greater than simply adding the individual effects of either condition.

- Between 50 and 80 percent of the savings can come from keeping people adherent rather than promoting adherence among those who are nonadherent.

- Health care organizations that bear financial risk for treatment costs and health outcomes (such as health insurers or ACOs) can see savings from improved adherence over a relatively short time (12–24 months).37

An estimated 86 percent of all health care spending is on patients who have chronic diseases, so engaging patients with these conditions early can have considerable cost-saving potential.

Executing a partnership

While structuring a partnership with a retailer is similar to other clinical integration efforts (for instance, with community physicians, specialists, or post-acute care providers), it will likely require focused commitment and dedicated resources. Compounding the challenge is that no standard blueprint for such partnerships yet exists. Our research has not uncovered many mature value-based care arrangements between health systems and retailers to deliver chronic care services. Most existing partnerships use retail clinics in their traditional capacity: as additional access points for minor acute care services. That said, even in this capacity, retail clinics bring a great deal of value to patients, health systems, and health plans. Providers that have engaged with retailers to date tend to have greater readiness and experience with value-based arrangements and a forward-looking population health orientation, and they express interest in expanding their relationship to take full advantage of capabilities at retail clinics that they may be underutilizing today.

We envision three main types of partnership models between health systems and retailers:

Contractual relationship. A retail clinic operator could contract with a health system as a member of its network with a risk-based performance contract. In this case, it would be the retail clinic’s responsibility to deliver results and make necessary investments in care delivery and quality reporting capabilities. The health system’s investment and amount of control over the retail clinic’s operations would be minimal. Health systems with a health insurance line of business or under full-risk contracts with private health plans or public payers should be able to contract directly with retail clinics.

Joint operations. A retailer and health system could jointly own and operate retail clinics (see sidebar, “Joint operating and affiliation agreement,” for an example). This model allows for varying degrees of collaboration and shared risk between the retailer and the health system. The health system’s investment would be greater than in the contracting model, as would its ability to control clinic operations, including the choice of new clinic locations, scope of services, branding, and staff recruitment and training. The retailer could draw on the health system’s clinical expertise, IT infrastructure, and possibly even staffing resources. This model may be combined with performance contracts.

Joint operating and affiliation agreement

When a health system in the southern United States first started thinking about retail presence, the options were to build, buy, or partner. It chose to partner. But as the system’s medical group CEO put it, “If we partner, we want it to look as if we built it.” From 2009 through today, the health system and retail clinic operator have worked closely together, and the partnership has thrived. “It wasn’t just cobranding and physician oversight,” said the CEO. “The retail clinic and the medical group shared similar cultures.”

The health system’s experience with its own ACO and health plan was a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for effective collaboration. All three partners (the retail clinic operator, the retailer, and the system’s medical group) worked together to build four critical pillars of success:

- IT integration. The health system and the retail clinic have recently moved into a health information exchange (HIE). With the HIE, the retail clinics will be part of the health system’s larger clinical and practice management system. When the clinics come across a patient with no PCP, they can schedule the patient to follow up with a physician within the health system network. For established patients, the HIE enables clinic nurse practitioners to view a patient’s entire health record and close gaps in care (for instance, administer appropriate screening tests and vaccinations).

- Clinical integration. To encourage physicians to collaborate with the retail clinics, the health system formed clinical protocol committees with clinician representation from each organization. The committees approve and periodically review pediatric and adult clinical protocols for the conditions treated at the retail clinics. Referral guidelines are also part of the clinical integration, to ensure that patients who need further care receive it at the most appropriate setting. Expanding the role of retail pharmacists to provide medication therapy management and diabetes education is the next priority.

- Shared workforce. The retail clinics employ nurse practitioners, but turnover is high. To counter this, retail clinic nurse practitioners are now job-shadowing clinicians at various sites throughout the health system. With their understanding of the health system's clinical and electronic systems, these nurse practitioners are now part of the health system’s supplemental work pool, and can pick up hours as substitutes in the health system’s different facilities.

- Marketing. When presented with many different sites where they can get care—retail clinics, urgent care centers, physician offices, emergency departments—patients who need care may not know where to start. The health system developed a marketing program to educate the public about the different levels of care available at many different sites, as well as where people could go to receive help in navigating the options.

As a result of this partnership, the retail clinic operator gained increased patient volume, access to a well-established brand, and training opportunities for its staff. The health system gained improved access to care for its existing patients, greater exposure to patients not already under its care, and a way to increase its physicians’ patient panels. With a robust portfolio of primary care services, the health system is now well positioned to operate in the value-based care environment.

Health system ownership. A health system could buy existing retail clinics from a retailer or lease retail space to set up its own clinics (see sidebar, “Health system-owned clinics,” for an example). Retailers that have already built their own retail clinic operations but no longer wish to own and operate them may consider selling these operations to a health system in their market. The health system would benefit from gaining already-set-up clinic spaces, and it would exert full control over clinic operations. This arrangement, however, requires the health system to have strong operational expertise in running retail clinics, which operate very differently from a physician practice, a community health center, or an urgent care facility. Not all health systems may have this expertise at the ready. Retailers could benefit from having retail clinics located in their stores without needing to develop or maintain the expertise and investment necessary to stay active as a health care provider.

Health system-owned clinics

Target and Kaiser Permanente have established a relationship that allows more people to receive more care with greater convenience.38 Target Care Clinics, with services provided by Kaiser Permanente, are located in several Target stores in Southern California.39

Patients who visit these clinics have access to a much broader array of services than are typically available at a retail clinic. Along with vaccinations and flu shots, these clinics offer pediatric primary care, OB-GYN services, and management of chronic diseases, including diabetes. All clinical staff are Kaiser employees. Unlike most other Kaiser facilities, services at these retail clinics are available to Kaiser members and nonmembers alike.

Kaiser's use of telemedicine in its retail clinics is its biggest differentiator. Patients seen at a Kaiser/Target clinic are not limited to seeing the staff on hand. Kaiser’s well-developed telemedicine technology enables onsite clinicians to reach Kaiser specialists and other clinical staff on demand.

For Kaiser, the value of these clinics lies in expanding access to their services. Creating an additional point of care in a high-traffic retail location also provides excellent exposure for its brand and an opportunity to attract new members. For Target, the benefit is the clinics’ ability to draw more customers into its stores.

Regardless of the way a partnership is structured, some considerations remain constant:

- Essential to an effective partnership is a health information technology infrastructure that can share clinical information and help support care coordination between partners. In fact, all major retail clinic operators have invested in electronic medical record (EMR) systems.40 Treatment protocols for the conditions cared for at retail clinics are embedded in the EMR. Operationally, however, the ability to share clinical data may be difficult depending on the provider’s and retailer’s EMR system.

We have the ability to share clinical information through our EMR with our affiliates. The patient understands that whatever happens at our clinic is sent to their physician. Because if there is a disconnect, they lose trust in us.—Retail clinic executive

- In many markets, local physicians serve as medical directors for retail clinics; these physicians are available for phone consultations and perform periodic reviews of patient charts. As retailers expand into chronic care, this model will remain relevant. The need for physician supervision and the amount and frequency of communications between retail clinics and physician practices are likely to increase.

- In a clinical collaboration with a health system, a retail clinic typically implements the health system’s protocols, ensuring consistent care regardless of where the patients are seen.41 Our research participants suggest that developing and agreeing on clinical protocols should be relatively straightforward, since retail clinics treat a limited set of common conditions.

- Similarly, establishing referral processes and incorporating them into the EMR or practice management software unlikely to cause difficulties, as typical referral relationships would involve retail clinics, health system-affiliated PCPs, and urgent care facilities.

- Devising and implementing value-based contractual arrangements can be complicated, and many organizations are still cultivating this expertise. Multiple factors need to be considered: determining patient attribution, estimating future utilization, applying appropriate quality metrics, and deciding how to share in the risk and the savings.

Stakeholder implications: Overcoming challenges

As health systems and retailers explore working together, they will encounter challenges. We envision that the following areas in particular will require thoughtful approaches to address:

Determining the business model

For retailers with existing retail clinic operations, expanding into chronic care could help diversify current clinic volume and offset declines that might come from competitors such as direct-to-consumer telemedicine providers or urgent care centers. Retailers new to operating retail clinics may have a somewhat different set of considerations, such as expanding their role in the community or increasing shopping trip frequency and and basket size.

Retailers’ main business focus may inform their clinics’ service orientation or priorities. For instance, drugstore companies may choose to focus on pharmacy-related services (such as adherence solutions, medication reconciliation, or pharmacist-led health coaching), whereas grocery retailers may be well positioned to specialize in nutritional counseling, health education, and community health events. Regardless, clinics can be a useful supplemental business for retailers whose purpose is to drive pharmacy volume and to increase foot traffic in the retail store. Emphasis on chronic care can potentially boost pharmacy volume, as it creates repeat business by improving patient adherence to maintenance medications. With this, the minimum goal may be for clinics to break even.

Developing quality and utilization targets

As part of value-based reimbursement, retail clinics would be measured on quality and utilization, raising the need to develop these measures so that they are reasonable and within retail clinics’ control. Few of our research participants suggested that retail clinics be designated as a primary care provider so that patients could be attributed to them. Without some level of patient attribution, holding retail clinics accountable for quality or utilization outcomes may be difficult; nonetheless, it can still be achieved. For instance, retail clinics’ contribution to quality metrics could be based on the proportion of total visits they deliver for the condition being measured, with eligible visits identified by diagnosis codes.

Achieving interoperability

Conceptually, retailers’ participation in the care continuum would be no different from that of partners in other clinical integration initiatives. The challenge of connecting disparate EMR systems is not unique to partnerships with retail clinics, and retail clinic operators appear to be further ahead than many community and ancillary providers on EMR adoption. Still, it will be important to allocate appropriate funding and personnel to integrating operations, as our experience suggests that organizations tend to underestimate the time and resources it takes to achieve interoperability.

Targeting and engaging patients who can benefit the most

For retail clinics to succeed at chronic care, it will be important to identify and engage patients who need additional support in managing their condition: for example, those who are not adherent to therapy, who are behind on regular testing and monitoring, or who have recently experienced a complication or hospitalization. Analytically identifying target patients, reaching them with communications, and developing customized incentives that would encourage them to come in for routine checks or health coaching would require coordinated efforts from traditional providers, retailers, and health plans.

Particularly challenging in this regard may be obtaining information on patient adherence. A health system may have a patient’s medical history, but information on care received outside of the health system’s clinical network may be unavailable, and outpatient drug data will almost certainly be missing. A health plan medical director we spoke with acknowledged that “providers have no idea whether patients refill their meds,” even though this is essential information for identifying nonadherence—an understanding of which is especially important if providers are held accountable for patient outcomes. Pharmacy utilization information on patients who fail to refill their medications or renew their prescriptions (for instance, information on medication possession ratio, gap analysis, or persistence)42 could be available from health plans, pharmacy benefit management companies, or retail pharmacies. However, sharing this information with providers is not the norm today.

Retail clinic capacity

Using diabetes as an example (see appendix), our analysis suggests that existing retail clinic capacity would be sufficient to absorb a modest amount of diabetes-related care. With retail’s potential to provide care for multiple chronic conditions, it is fair to ask whether current capacity is sufficient to provide chronic care at scale for all the conditions that retail clinics may wish to pursue. Even given the current growth trend, it is unclear whether or how soon retail clinics would reach the critical mass to be a notable player in chronic care, or primary care more broadly.43

For retailers and health systems, as the most likely contributors to new retail clinic capacity, key considerations may include:

- With whom should we partner?

- What partnership model and what types of value-based contracting arrangements make the most sense?

- Should the partnership be exclusive?

- Should all services be available to all customers, or should some services (such as disease management) be offered exclusively to partners’ patients or members?

Conclusion

With the accelerating transition to value-based payment models, close clinical integration between primary care and retail clinics is no longer an abstract concept. By joining forces, retailers and health systems can improve chronic care and potentially overcome the challenges of high cost, poor access to care, and low patient engagement. Retailers can serve as a cost-effective, consumer-friendly extension of primary care. Health systems can provide clinical leadership, physician engagement, and the ability to coordinate clinical information. And health plans can do their part by sharing a longitudinal view of patients’ data.

Appendix. Diabetes: Where might savings from retail lie?

How might retail clinic-based chronic care change the US health care landscape going forward, particularly with respect to the cost of care? As an illustrative example, we used data from the 2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to estimate annual medical spending associated with diabetes today and how that spending might change if diabetes-related services became widely available in retail clinics.44

Simple replacement of office visits with retail visits would generate a range of savings, depending on the volume of visits being replaced. With retail clinics’ low per-visit cost ($79), compared to that of a physician office visit ($160–$230), the savings could be over $100 million ($7 per person per year) under conservative assumptions and as high as $2.7 billion ($164 per person per year) if half of diabetes-related office visits migrated to retail clinics.

More-frequent patient visits, as opposed to simple replacement of office visits with clinic visits, may be neutral from a cost perspective, but can lead to improved diabetes control as well as substantial savings on other medical services. Studies that take into account the long-term savings potential of reduced or delayed complications of diabetes project savings of up to $1,200–$1,900 per person per year.45

As figure 3 shows, prescribed medicines account for the largest portion of overall diabetes-related expenses. Office visits constitute the second-largest share of medical expenses. Utilization of emergency rooms (ERs) and hospitals represents a small proportion of visits (1 percent), but a sizeable share of the costs (19 percent when drugs are factored out).

We modeled two scenarios of how diabetes-related expenditures may change if retail clinics played a bigger role in the provision of chronic care services:

- Replacing physician visits with less-expensive retail clinic visits for a small proportion of patients

- Replacing physician visits with retail clinic visits for a large proportion of patients

Our analysis used data from the 2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a nationally representative survey of the US civilian non-institutionalized population administered by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS gathers information on use of medical care, medical spending, demographics, socioeconomics, and health conditions.

In this analysis, we included only those health care encounters where diabetes was a reason for the visit. Thus, we report only diabetes-related utilization for people with diabetes and not their total health care utilization.

Because we used average per-visit rates to estimate current expenditures, we did not make distinctions between different levels of visits based on complexity, or the different mix of visits. In medical billing and reimbursement, visit complexity is expressed through evaluation and management (E&M) codes: Higher codes reflect greater complexity or intensity of the services performed during the visit. It is common for physician offices to employ nurse practitioners, who typically use less-intensive E&M codes for their services than do physicians. We also did not account for different payment rates between specialists (such as endocrinologists) and PCPs. Specialists tend to care for patients with more complex needs than do PCPs; additionally, the use of specialists, PCPs, and nurse practitioners may depend on clinician supply in specific markets as well as on patient choice.

For office-based visits, we used per-visit payment amounts derived from the MEPS survey. For retail clinics, we assumed a mix of simple and complex visits, so we chose a mid-range payment amount of $79 based on current retail clinic pricing. (Retail clinic rates range from $44 for blood glucose screening and consultation, to $59 for an A1c check, to $70–$150 for a comprehensive diabetes screening and counseling exam.)46

We focused on three consumer cohorts who receive care for diabetes:

- Individuals 45–64 years of age covered by private health insurance

- Individuals under 65 years of age covered by Medicaid

- Individuals 65–75 years of age covered by Medicare (both traditional and Medicare Advantage)

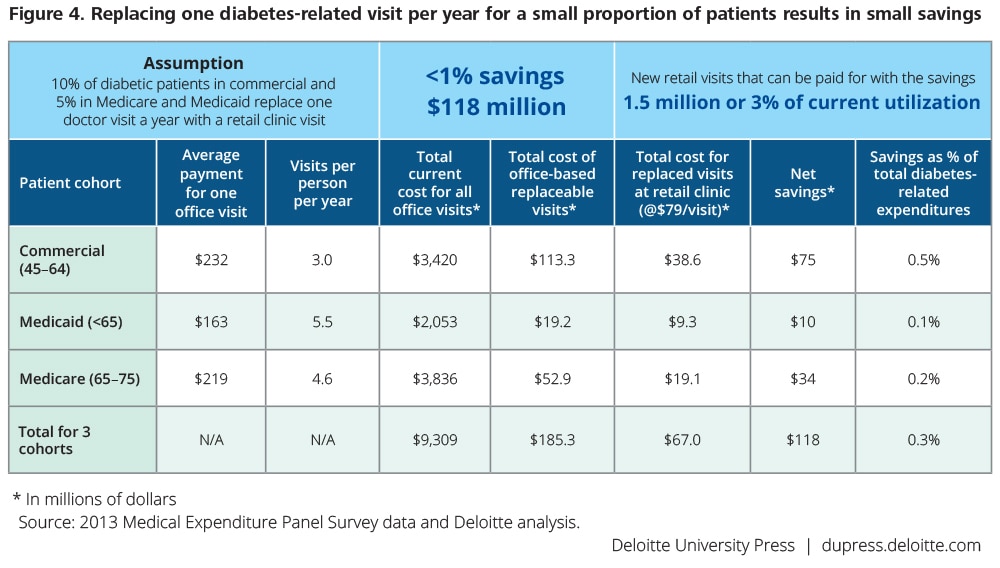

Scenario 1. Replacing physician visits with retail clinic visits for a small proportion of patients

In this scenario, we modeled a simple substitution of retail clinic visits for physician visits by a small proportion of patients. This analysis shows how this substitution can result in saving over $100 million a year.

We assumed higher use of retail clinics among the commercially insured (10 percent replacing one physician visit a year with a retail clinic visit) than among individuals covered by Medicare or Medicaid (5 percent replacing one visit). Commercial health plans are more likely to employ benefit design features, such as lower copays or discounts on diabetes drugs, that steer members to retail clinics. Such features are less likely in publicly administered health programs.

This modeling scenario points to the possibility of relatively small savings of $118 million (less than 1 percent of overall diabetes-related expenditures, or $7 per person per year) and offers a plausible projection of initial uptake of retail clinics’ chronic care offerings. The total number of visits migrating to retail clinics in this scenario is under 850,000, or fewer than 450 per clinic per year. Existing retail clinics should be able to absorb this volume comfortably.

It is possible, however, that current utilization is not sufficient to support desired health outcomes. The literature suggests that between 33 and 49 percent of diabetic patients do not meet targets for glycemic, blood pressure, or cholesterol control, and only 9–12 percent of patients maintain all three measures at goal.47 Very frequent visits—as often as every two weeks—are associated with better control.48

To expect a patient to have great outcomes after 15 minutes with a physician twice a year is not possible.—Pharmacy benefit management and pharmacy executive

Higher visit frequency would mean new utilization. Under the scenario in figure 4, the savings could be used to pay for 1.5 million new visits at retail clinics, a 3 percent increase in overall utilization, without adding cost. In this case, the combined volume of replaced and new visits would equate to 2.3 million diabetes-related visits, or more than 1,200 visits per clinic per year. This demand may still be possible to meet with the current number of retail clinics in the United States (2,009 clinics as of 2015), but it may stretch their capacity.49

Scenario 2. Replacing physician visits with retail clinic visits for a large proportion of patients

A very aggressive utilization shift, unlikely in the short term, could generate much larger savings than scenario 1 projects. If half of all office visits for diabetes took place in retail clinics, the savings could reach $2.7 billion ($164 per person per year), or 6 percent of overall expenses. The savings would be larger for commercial health plans ($1.1 billion, or 7 percent) and Medicare (also $1.1 billion, 7 percent) than for Medicaid ($530 million, 4 percent). However, existing retail clinic capacity may not be sufficient to accommodate this volume.

Caveats

It is possible that reducing barriers to care could invite new utilization from patients who are already well controlled and may not benefit from additional visits. Increase in overall utilization has been observed in care for low-acuity episodic conditions at retail clinics: Improved access to care (due to convenient locations and hours as well as low cost to consumers) has resulted in higher overall expenditures despite low per-visit cost.50 While we acknowledge this possibility, we are not aware of studies that estimate the extent of new “non-beneficial” utilization in the case of diabetes when barriers to care are removed or reduced. On the contrary, research suggests that increases in patient interactions, screening, and monitoring are associated with improved outcomes.51

We do not quantify the effects on prescription drug spending or make projections about the rate of diagnosing new diabetes cases. New utilization from increased visit frequency among patients with an existing diagnosis of diabetes or from newly diagnosed patients could lead to higher utilization of prescription drugs and higher costs in the short term. In the long term, however, this should result in improved outcomes and better quality of life for the patients.52

Current expenditures and the ratio of medical to pharmacy spending may be different for other chronic conditions, so the effects of retail clinics on the cost of care for those conditions may deviate considerably from what we project in the case of diabetes. Retail clinic fees may vary from what we used in our analysis and may change over time.

In this analysis, we focus on direct medical expenditures related to diabetes over a short time horizon. We do not quantify savings from the reduction in medical costs due to avoided or delayed diabetes-related complications. Other studies estimate that about 20 percent of diabetics’ medical costs is due to diabetes complications, and that only 9–12 percent of diabetes patients meet all three recommended diabetes control measures (A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol). These studies estimate that improved diabetes control could reduce the incidence of complications, yielding annual per-patient savings of $804–$1,260 in the commercial population and $1,188–$1,896 in the Medicare population.53 The savings projected by these researchers could be even greater if some diabetes-related care took place at retail clinics.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.