Volume- to value-based care: Physicians are willing to manage cost but lack data and tools Findings from the Deloitte 2018 Survey of US Physicians

11 October 2018

In the shift to value-based care reimbursement models, physicians say they lack the cost information needed to be successful. Explore our 2018 survey of physicians, including the data needed to drive this transformation.

Executive Summary

Value-based payment models require physicians to deliver the best outcomes while managing resources appropriately. Physicians have long focused on quality of care, but in a relatively new development, they now have to pay attention to resource utilization as well, with the goal of reducing overall cost of care. To succeed at this, they need data on health care costs, tools to analyze costs related to outcomes, and aligned financial incentives.

Learn more

Explore the 2018 surveys of US health care consumers and physicians

Visit the Health care collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

The Deloitte 2018 Survey of US Physicians found that two-thirds of physicians get some quality and productivity information:

- Sixty-six percent receive information on their own quality performance.

- Sixty-seven percent receive data on their own productivity.

But the situation is considerably different for cost-related information:

- Seventy-two percent of physicians consider cost data valuable, particularly at the point of care.

- However, only 28 percent receive cost information, such as cost or resource use for their attributed patients, for physicians and facilities to which they refer, or estimated patient out-of-pocket costs.

- Lack of information limits physicians’ ability to perform certain tasks: Forty-three percent of respondents say they are not able to find low-cost lab and imaging options and 36 percent cannot identify high-quality skilled nursing facilities, rehab, or home health.

“You can’t manage what you can’t measure” is as true for physicians as it is for administrators. They need, and want, better tools to deliver value-based care. As data and analytics capabilities mature, sharing actionable insights with physicians can help them make better patient-care decisions. Health systems, health plans, and public payers have room to improve in sharing information with physicians, particularly on the cost of care.

A comprehensive toolkit that includes resource utilization and information related to cost of care could help physicians succeed under value-based care. Other tools might include technology and appropriate staff resources, improved processes, education, and care management support. Health systems should consider moving from simple bonuses to comprehensive performance management programs that include balanced score cards, goal-setting, rewards, and meaningful financial incentives.

Introduction

Policy and payment reform drives much of the health care industry’s move toward value-based care—providing the best outcomes at an optimal price. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015 changed the way Medicare pays clinicians. Rather than just paying for volume, Medicare rewards physicians who provide lower-cost care of higher quality and who join organizations that bear the risk for their performance.1 The requirements to achieve the highest payments are increasing.2 While not included in clinicians’ overall Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) score in 2017, cost measures will account for 10 percent in 2018 and 15 percent in 2019.

As Medicare implements rule changes to reduce overall costs, commercial payers and providers are moving in this direction as well. For example, the Texas Hospital Association piloted the sharing of relevant cost data with physicians at a large academic hospital directly through electronic health records. In just over two months of the pilot’s launch, the hospital saved US$430,444.3

About the study

Since 2011, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions has surveyed a nationally representative sample of US physicians on their attitudes and perceptions about the current market trends impacting medicine and future state of the practice of medicine.

The 2018 Deloitte Survey of US Physicians included 624 US primary care and specialty physicians practicing in a variety of health care settings. The survey is representative of the American Medical Association Masterfile with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty.

Findings

Findings from Deloitte’s 2018 Survey of Physicians offer insights on physician experience and perspectives on resources, tools, behavior-change levers, and compensation.

Physicians want, but lack, data on health care costs

As physicians are increasingly asked to provide cost-effective, quality care, they need both quality and cost data to make informed decisions. While two-thirds of respondents have access to their own productivity and quality performance data, cost information is not as abundantly available. Only 28 percent receive at least one of the cost-related types of information presented in the survey (figure 1): cost or resource use for their attributed patients (20 percent), cost or resource use of the physicians and facilities to which they refer (9 percent), or estimated patient out-of-pocket costs (6 percent).

The survey also found that lack of information limits physicians’ ability to effectively perform certain tasks: For instance, 43 percent of our survey respondents say they are not able to find low-cost lab and imaging centers, and 36 percent cannot identify high-quality skilled nursing facilities, rehab, or home-health options in their normal workflows. Many physicians are not even involved in these tasks: 31 percent and 41 percent, respectively, don’t know or leave it to somebody else at their organization to locate these options. And these are just two examples of referral decisions that may impact a physician’s performance on cost measures in MIPS.

When asked what types of information would be valuable at the point of care, survey respondents ranked cost (63 percent) and outcome (56 percent) data for treatment and medication options, as well as estimated patient out-of-pocket costs (56 percent) as most valuable (figure 2). In total, 72 percent of physicians consider some type of cost-related information valuable at the point of care.

Data can drive behavior

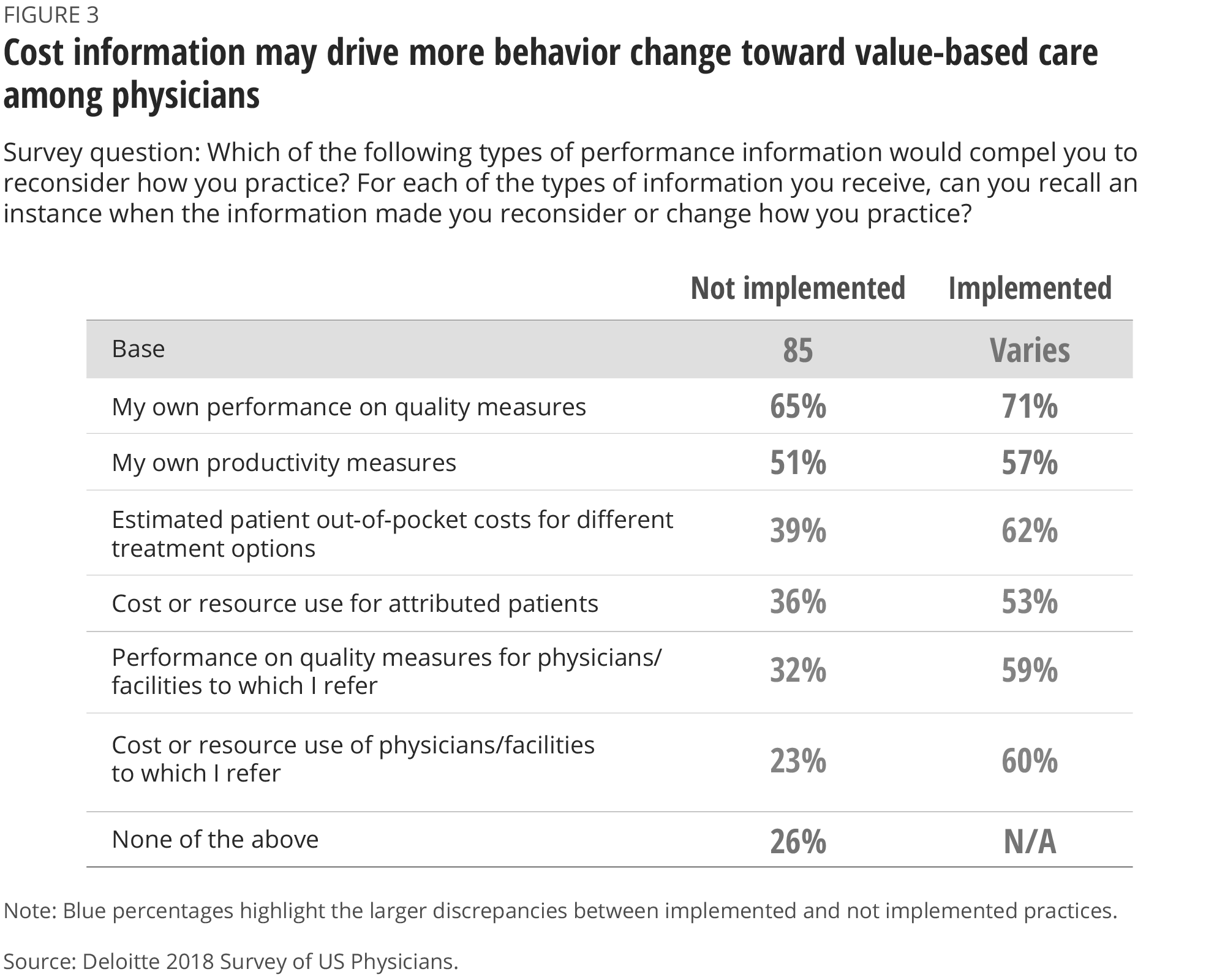

Though many survey respondents say that information on quality, productivity, and cost can help them improve the way they practice, physicians without access to data tend to underplay the likely impact of data on their behavior compared with physicians who currently receive this data (figure 3). A large proportion of physicians (53–62 percent) receiving cost-related information say that they have reconsidered or changed the way they practice as a result of this information. But a far smaller proportion of physicians without access to this data (23–39 percent) expect such information to compel them to change their practice. This suggests that once physicians get access to cost-related data, they will recognize its value.

Organizations that already provide some cost data to their physicians observe that while this data can influence practice patterns, it requires education and takes time. Certain types of cost data and the way it is reported can be complicated: Methodological constructs of resource use, care episodes, patient attribution, benchmarks, and severity adjustments may require explanation about how they are derived, how they affect patient care and an organization’s overall performance, and why physicians should pay attention.

Physician responses about the type of content that would compel them to reconsider how they practice, indicate that this data should be accurate, actionable, and easily accessible. They call for:

- Measures that they can impact or are within their control (78 percent);

- Measures relevant to their service line or specialty (68 percent), particularly among specialists;

- Specific action steps (56 percent);

- Data/information at the point of decision-making (43 percent); and

- Reports accessible through regular practice workflow (39 percent).

In addition to data, a number of other levers could influence physician behavior:

- Financial incentives, whether through sticks or carrots (78 percent);

- Tools and resources that help physicians provide excellent care, such as additional staff for care coordination and decision-support tools (71 percent);

- Educating physicians about specific practices and approaches that improve performance and outcomes (66 percent);

- Reports that compare a physician’s performance against peers (51 percent);

- Confidence that the best possible care is being provided to patients (50 percent); and

- Attitudes and behavior of respected physician colleagues or mentors (42 percent).

Only 1 percent say nothing can influence the way physicians practice.

Physicians are ready for a little more financial risk

While financial incentives can be major drivers of change, survey respondents report that these incentives do not have to be large to influence behavior. For example, most physicians said they were willing to tie more risk—around 10 percent of total compensation—to quality and cost measures.4 This threshold is higher than the average amount of physician compensation linked to performance goals today: Seventy-one percent of physicians either receive small performance bonuses of up to 5 percent (43 percent) or are not eligible for bonuses altogether (28 percent).

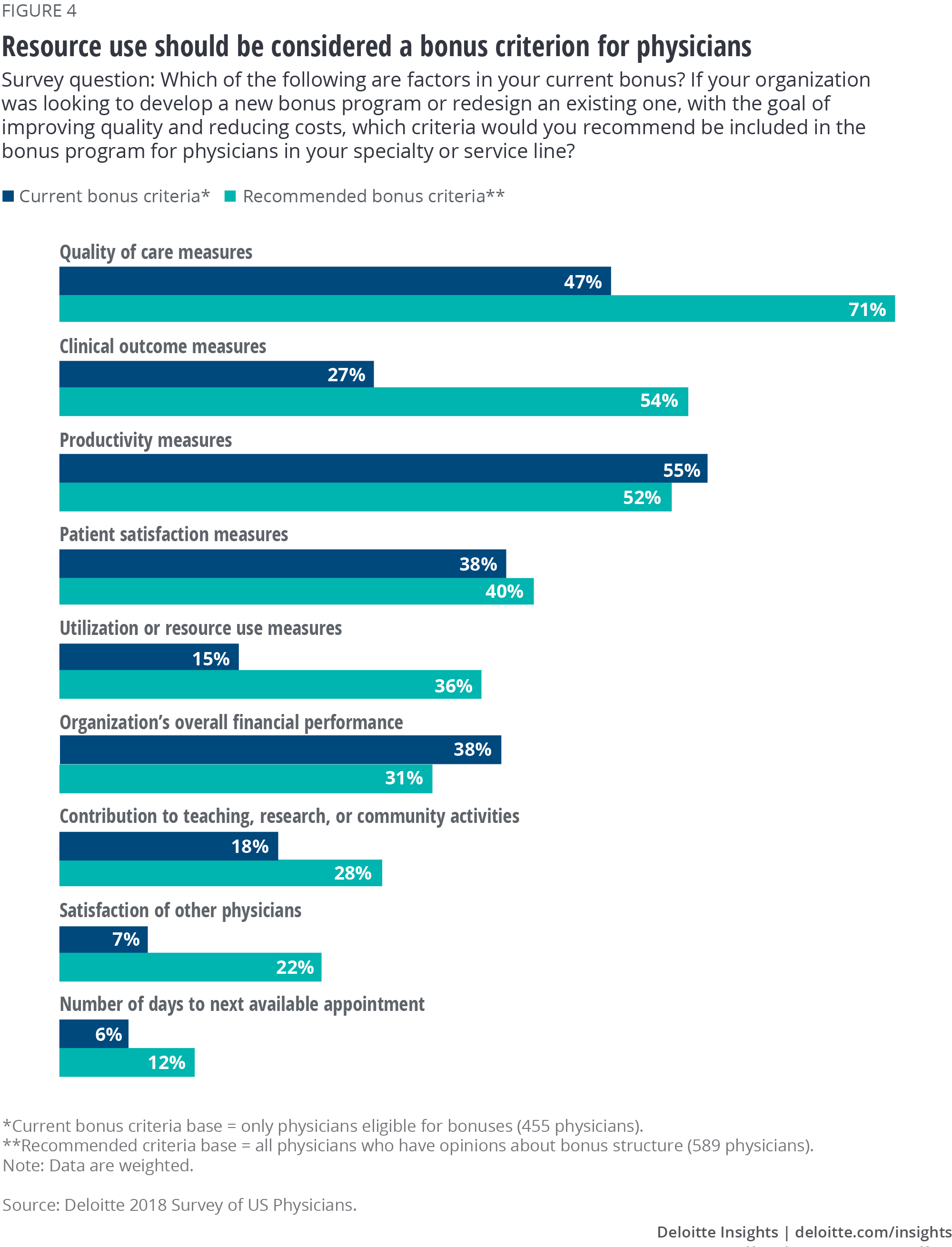

Those eligible for performance bonuses cite productivity (55 percent) and quality (47 percent) measures as the most common bonus criteria. We also asked physicians which criteria they would recommend for bonuses, and the largest gaps between current and recommended bonus criteria are for clinical outcome measures, quality of care measures, and utilization or resource use measures (figure 4). The recognition of the need for data on utilization measures demonstrates a growing understanding of its importance.

Deloitte expects financial metrics, such as cost and the organization’s overall financial performance, to become more prominent in physician bonuses over time.

Today’s compensation underemphasizes value

As in 2016, survey respondents report that value-based arrangements remain a less common source of physician compensation than traditional sources of payment (salary or fee for service).

- Prevalence of salary as a source of compensation has increased from 59 percent in 2016 to 68 percent in 2018.

- Fee for service has declined from 52 percent to 42 percent.

- The total number of physicians who cited salary and/or fee for service as a source of compensation was nearly unchanged from 2016.

- Prevalence of value-based arrangements (31 percent) as a source of compensation has also not changed.

This may reflect the slow translation of value-based care incentives into physician compensation. Several studies suggest that actual progress has failed to keep pace with expectations5 or that there is variability in adoption.6 Anecdotally, failure to align physician incentives with organizations’ own reimbursement has prevented some value-based contracting success.7

Conclusion

Physicians are willing to manage health care costs, but to do so successfully, they need more cost data in addition to other ingredients essential for a successful transition to value-based care: clinical decision support, education, staffing, and technology resources to help with patient care and care coordination, along with aligned incentives.

Health systems should consider moving physician compensation from simple bonus structures into comprehensive perform ance management programs with balanced score cards and mutually agreed upon goals and rewards. The following principles can be useful in designing performance management programs for employed physicians:8

- Incentives to drive the desired behavior. Organizations should maintain a strong focus on performance by increasing transparency on performance and recognizing and celebrating strong performers. They should also ensure timely access to individual, group, and organizational performance scorecards.

Performance metrics and financial incentives should be aligned with the strategic goals of the organization, service line, and department. Health systems should translate high-level goals for physicians and clearly communicate the link between physician performance and health system strategy. Rewards for achieving key milestones, such as patient-centered medical home (PCMH) accreditation and technology implementations, need to be in place and financial incentives such as bonuses and at-risk amounts should be significant enough to attract physicians’ attention.

Noncash rewards, such as benefits, work environment, and professional development, can help attract and retain physician talent.

- Measurable metrics. A manageable and measurable number of metrics with realistic performance thresholds should be set up front. Tiered performance thresholds, such as “excellent” and “acceptable” are a good practice.

- Encouraging team-based care. Attributing performance to groups when appropriate can help account for practice styles that call for group attribution, such as rotating hospitalist jobs.

Experience suggests that supplying this data to physicians, whether independent or employed, can help improve their performance. When working with independent physicians, health systems strive to become the referral destination of choice, a place where these physicians would send not only their patients, but where they would seek care for themselves and their families, or a place where they want to perform surgeries.9 Some of the same principles apply: alignment on strategic goals, transparent performance reporting and peer comparison, and meaningful financial incentives through inclusion in tiered networks and gainsharing. All physicians are being measured by payers, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, on their utilization and cost performance; giving independent physicians access to appropriate data to provide both better quality and cost outcomes could be a differentiator for provider organizations.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.