Moving beyond marketing has been saved

Moving beyond marketing Generating social business value across the enterprise

16 July 2014

The 2014 MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte social business study reveals three drivers of social business maturity—and a strong connection between social business maturity and social’s value to the enterprise.

See the related infographic. View interactive visual analytics of the survey data.

Join the conversation

Follow #SocBizStudy on social mediaExecutive Summary

This year’s MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte1 global survey found clear evidence that companies across industries are creating value with social business. A key finding is that social business value is a function of what we call social business maturity — the breadth and sophistication of its initiatives. In this year’s report, we detail the drivers of that maturity and how companies are using social business to transform their organizations and reap greater gains from their social business efforts. The following are highlights of our findings:

Social Business Grows Deep Roots

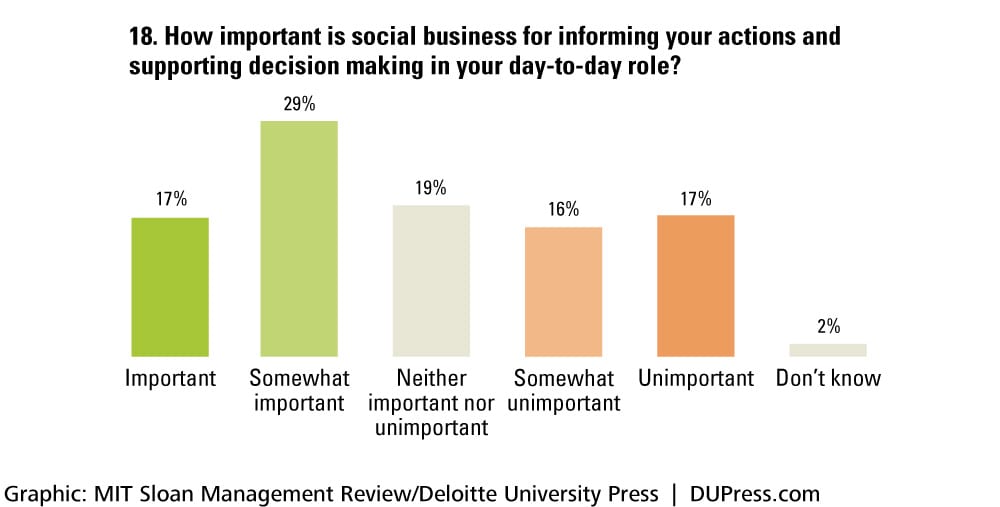

Social business is perceived as important both today and in the future. After jumping from 52% in 2011 to 74% in 2012, 73% of this year’s survey respondents say that social business is important or somewhat important today. Nearly 90% see its importance on a three-year horizon.

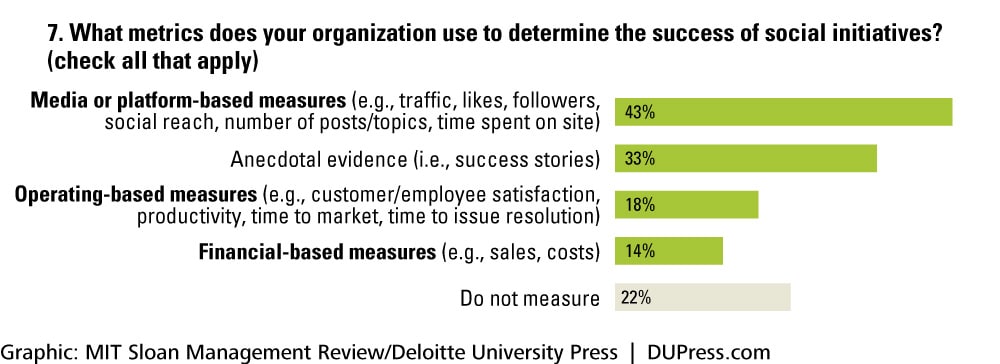

Measurement sophistication is starting to prove its value. In our first survey, “do not measure” was the most common response to questions about social business measurement. While more than half of the least socially mature companies in this year’s survey don’t measure their efforts, more than 90% of maturing companies actively do. These organizations are using a battery of measures, such as operational and financial metrics, to connect social initiatives to business outcomes. We also found a surprising common denominator among all companies, including the most socially mature: anecdotal evidence plays a major role in demonstrating the value of social business.

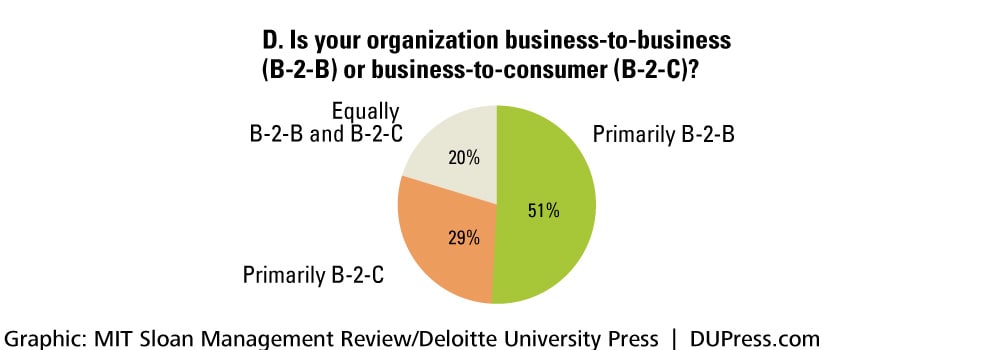

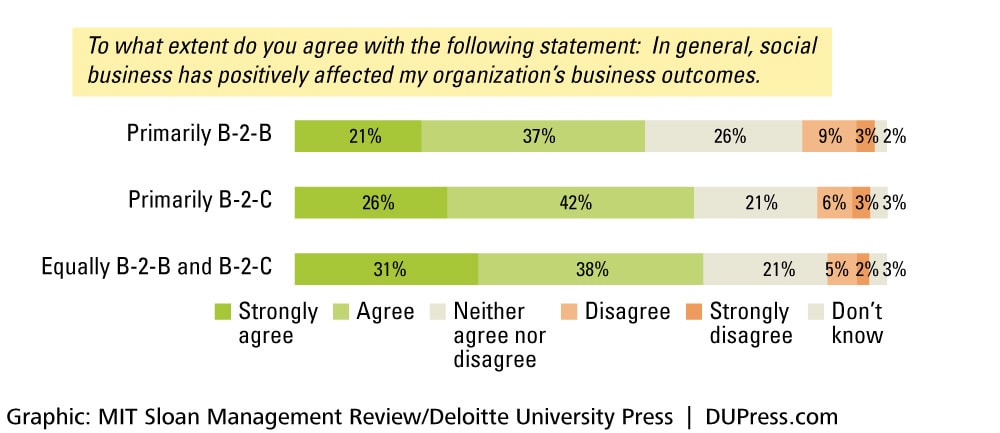

Social business is not just a B-to-C phenomenon. In our two most recent annual surveys, we found that social business is important to very similar levels of respondents from B-to-C (business-to-consumer) and B-to-B (business-to-business). The impact of social business in these sectors is also comparable: nearly 60% of B-to-B companies agree or strongly agree that social business initiatives are positively impacting business outcomes. Among B-to-C respondents, the percentage is 68%.

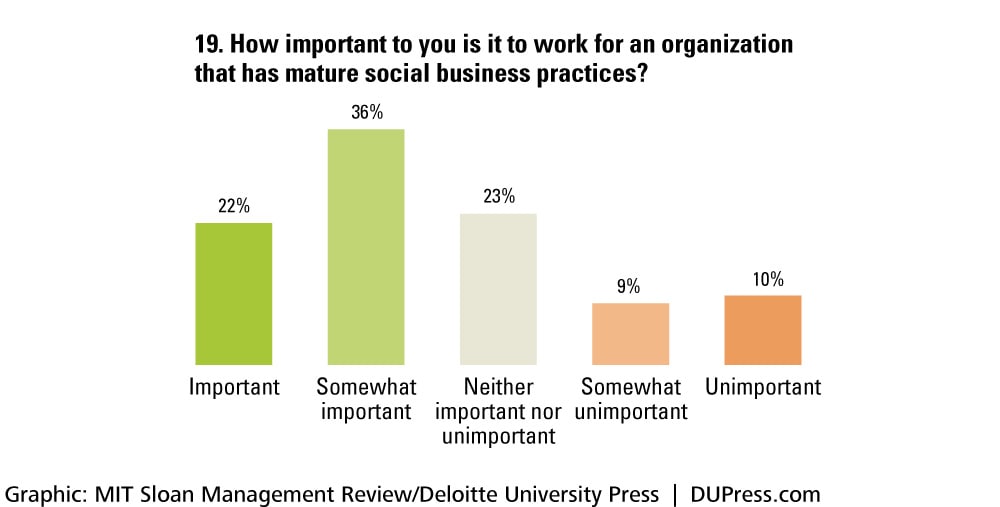

Employees want to work for companies that excel at social business. Some 57% of respondents say that social business sophistication is at least somewhat important in their choice of employer. That attitude is consistent among respondents aged 22 to 52.

Social Business Maturity Translates Into Value

Social business maturity is related to the level of results companies achieve. The higher respondents rate their companies on a social business maturity scale, the more likely they are to report that social business creates real value.

Companies can advance toward social business maturity by focusing on its three primary drivers:

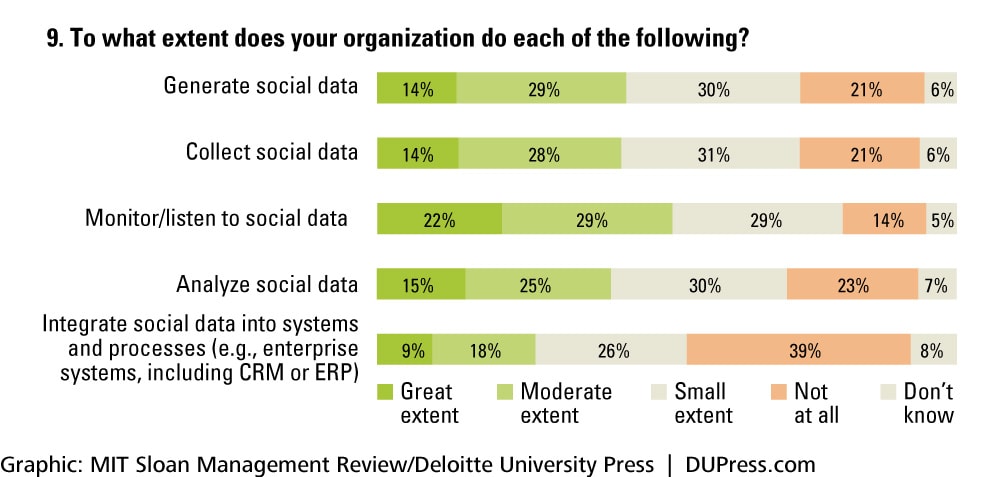

Using social business to help make decisions: Maturing social businesses are not simply “doing social.” Nearly 80% analyze social data and 67% integrate it into systems and processes to improve business decisions and drive social business endeavors.

Having a leadership vision premised on the belief that social can fundamentally change the business. More than 90% of respondents from maturing social business companies say their leaders believe it can create powerful and positive change.

Moving social business beyond marketing to realize that vision. Maturing companies are infusing social business into multiple functions across the enterprise:

- 87% use it to spur innovation.

- 83% turn to social to improve leadership performance and manage talent.

- 60% integrate social business into operations.

Introduction: A story of social business value

Hearing tornado warnings and reports that some twisters were touching down in her area, a young baby-sitter began to panic. With three small children in her care, she realized she didn’t know how to ensure their safety. Instinctively, she tweeted nervously for advice. Her tweets were picked up by the American Red Cross digital command center in Washington, D.C. Within minutes, the disaster-relief organization responded with advice on how to remain safe and assurances that it was standing by to help.

Some seven years before, in 2005, social media was consigned to the Red Cross’ communications unit — as it is in many businesses today. Social business was, as the Red Cross’s Wendy Harman quips, “a bubble outside the organization’s structure.” Harman was tasked to improve the work in that bubble. Senior leaders were concerned about negative sentiments moving through the blogosphere about the Red Cross’s response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The organization needed someone with expertise in correcting public misperceptions in the fast-paced world of digital media.

Harman did just that but also saw a bigger opportunity. The vast majority of online postings mentioning the Red Cross were distinctly positive. Understanding how social communities can appeal to people’s desire to contribute to something greater than themselves, she saw how social business could harness the public’s positive feelings about the Red Cross to change the face of how it operates. Today, social business anchors a strategy that the Red Cross calls “turning the organization’s mission over to communities” — mobilizing people in huge numbers to help prepare for and respond to disasters.

The idea is to infuse and integrate social tools into the entirety of what the organization does. -Wendy Harman, director of management and situational awareness, American Red Cross

The organization’s digital command center is the fulcrum of the strategy. Launched in 2012, it was the first social media operation dedicated to humanitarian relief. Housed in the larger Red Cross operations center in Washington, D.C., the digital command center generates data that are monitored around the clock. By tracking Twitter keywords such as “tornado,” for example, the center can readily spot where disasters are happening and anticipate public needs.

Monitoring is only part of the picture, however. The command center also connects citizens in need to a growing cadre of digital volunteers. The Red Cross has trained some 200 of these volunteers across the country. Via social media, each volunteer can respond to questions, distribute critical information and provide comfort and reassurance during an emergency. In the future, the Red Cross plans to build this corps to include volunteers on every street and even every apartment building in the country.

What is Social Business?

We define “social business” broadly to include activities that use social media, social software and technology-based social networks to enable connections between people, information and assets. These activities could be internally focused within the enterprise or externally focused toward customers, suppliers and partners. Examples include:

- Social media: Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter

- Social software: Instant messaging, wikis, blogs, enterprise collaboration platforms

- Technology-based social networks: employee and community forums

We call the value that companies derive from these activities social business value.

Social business is also revamping the complex logistics of managing trucks and personnel in a disaster. During Hurricane Sandy, for example, many New Yorkers on flooded streets couldn’t physically see a Red Cross truck even though one might have been a block away. So the organization called its response vehicles every hour to identify their locations and assess their inventories of supplies. The Red Cross then tweeted that information and posted it on its websites and social media communities to help those in need find the nearest truck.

The Red Cross experience is a prime example of what this year’s global survey of executives revealed about creating social business value. Namely, that social business value stems from what we call social business maturity — the sophistication of social business initiatives. That maturity is driven by three interrelated actions, exemplified by the Red Cross:

Using social data as the basis of business decisions: The Red Cross doesn’t simply monitor public sentiment. It uses social data to identify disasters and determine how to respond to people in need.

Having leaders committing to social business as a means to change how the organization operates: Red Cross leaders see social business as a means of mobilizing citizens and preparing communities to respond to disasters. That commitment is also visible to employees.

Moving social media beyond marketing to create a holistic social business: Although the Red Cross initially used social media in marketing and fundraising efforts, it now integrates social into core operational activities, including mobilizing communities and managing the logistics of its trucks and supplies.

The Advance of Social Business: A Three-Year Lens

For the past three years, MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte have conducted annual surveys charting the rise of social business. Analyzing our findings from these years, we found that the use of social business, including advances in the sophistication of social business measurement, is deepening across industries. (See “About the Research.”)

A Deep and Wide Trajectory

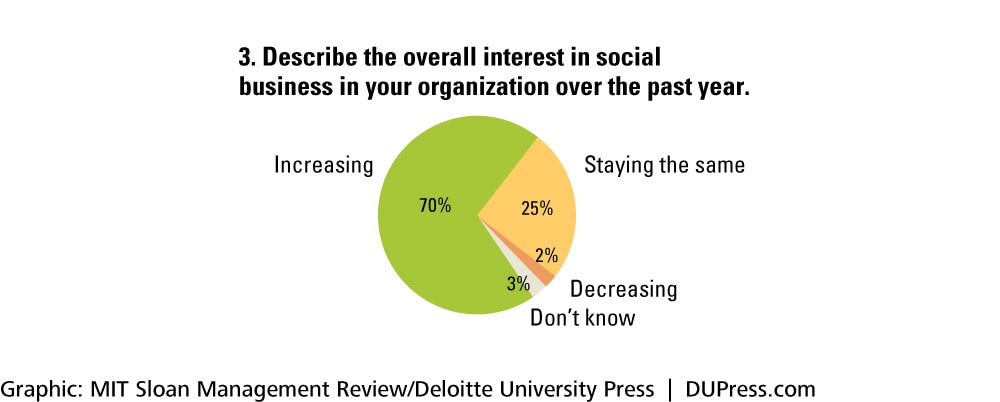

Over the years, the perceived importance of social business has grown considerably and remains high. The percentage of respondents saying it is “somewhat important” or “important” to their business today jumped from 52% in 2011 to 74% in 2012. In this year’s survey, conducted in 2013, the sentiment was almost equally high — 73%.

The projected future importance of social business to companies is pronounced. Some 70% of respondents report growing social business interest within their organizations in the past year. When asked to assess the significance of social business for their company on a three-year horizon, the vast majority of respondents see its future importance: 86% in 2011, 88% in 2012 and 89% in 2013.

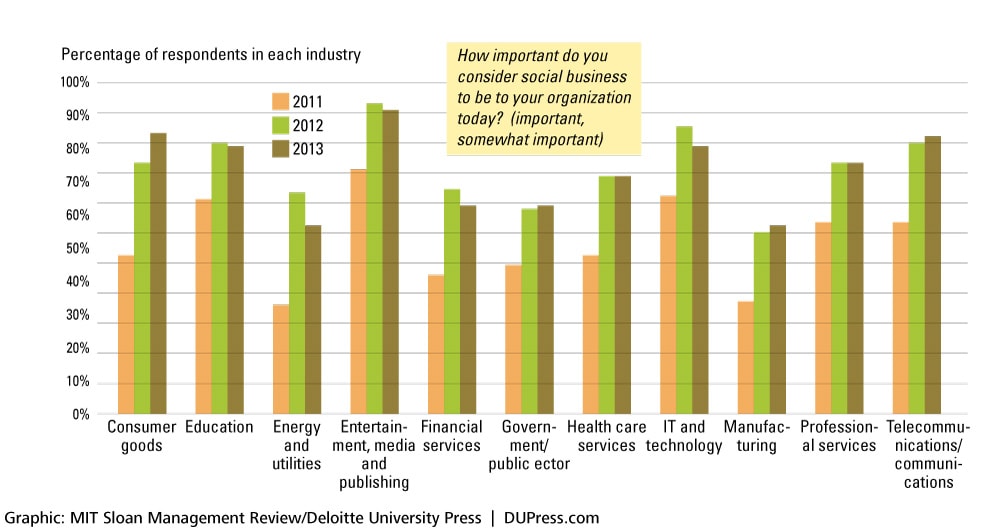

Although the industries at the forefront of social business have been consistent over the years — technology, media and telecommunications — newcomers continue to move up the ranks. (See Figure 1.) Last year, for example, energy and utilities moved up the list. Consumers are increasingly demanding that utilities connect with them via social media, and utilities report seeing social’s value in improving crisis communications and educating consumers about energy efficiency.

FIGURE 1: INDUSTRIES CONTINUE TO ACKNOWLEDGE SOCIAL BUSINESS IMPORTANCE

Respondents were asked to rank the importance of social business to their organizations on a five-point scale. Similar to last year’s survey, this year we found that at least 60% of respondents in most industries agree that social business is important or somewhat important today (four or five on a five-point scale). In the IT and technology, Entertainment, media and publishing, Telecommunications, Consumer goods and Education industries, the percentages exceed 80%.

This year, consumer finance and banking came onto the radar. This was in the wake of eased regulations around the use of social media by financial companies established by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. “The regulations and guidance are setting parameters that define safe boundaries for experimentation,” says Kelli Carlson-Jagersma, vice president of internal collaboration at Wells Fargo & Co. “In regulated industries, content may still be king, but regulations are your best friend.”

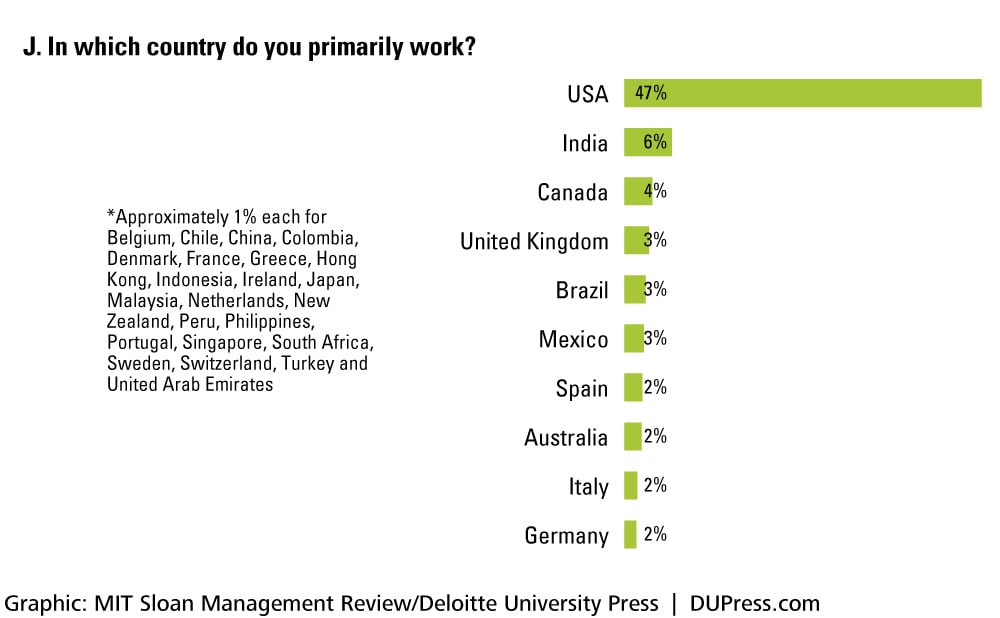

The advance of social business is a global trend. In fact, to our surprise, we found that interest in social business may be stronger elsewhere than in the U.S. The percentages of U.S. versus non-U.S. respondents who believe social business is important or somewhat important today is roughly equal (about 75% each). However, managers outside the U.S. see greater potential in social business and are more likely to be using it. For example, nearly three-quarters of respondents outside the U.S. agree or strongly agree that social business represents an opportunity to fundamentally change the way their organization works. In the U.S., 61% hold that view. Non-U.S. respondents are also using social more frequently — 52% say it is important or somewhat important in making daily decisions versus 40% among U.S. respondents.

Equally telling of social business’s advance is the fact that employees want to work for organizations that are good at it — 57% of respondents say this is at least somewhat important. The desire isn’t limited to millennials: An employer’s social business savvy is equally important to respondents ranging in age from 22 to 52.

The B-to-C Myth

Since social media has become so pervasive among consumers, social business is often seen as a B-to-C (business-to-consumer) phenomenon. Our survey results have challenged that notion. In our two most recent annual surveys, respondents from B-to-C and B-to-B (business-to-business) companies share similar views about the importance of social business. In addition, a substantial percentage of B-to-B respondents report that their companies are creating value with their social business initiatives. That percentage is surprisingly close to the number of B-to-C respondents making similar reports. (See Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2: B-TO-B AND B-TO-C COMPANIES ACHIEVE COMPARABLE VALUE FROM SOCIAL BUSINESS INITIATIVES

B-to-B companies are leveraging social business both within their organizations and outside them. Common uses of B-to-B social business include knowledge sharing, collaborating with business partners and using social data analysis to inform product development. In previous reports, we detailed several strong B-to-B social business initiatives.

SAP, for example, developed an online developer community where millions of users of its enterprise software share ideas and help. Recruiters at Covance, a drug development services company, turned to tweets to connect prospects to company scientists and create relationships based on scientific curiosity and dialogue. This year, we saw similar activity from enterprise collaboration platform veterans BASF SE and The MITRE Corporation. BASF, a global chemical company, has developed a social business platform to improve its operations worldwide. MITRE, a $1.4 billion nonprofit that operates federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs), is using a social collaboration platform developed in-house to increase innovation among its government, industry, academic and other FFRDC partners.

Growing Measurement Sophistication

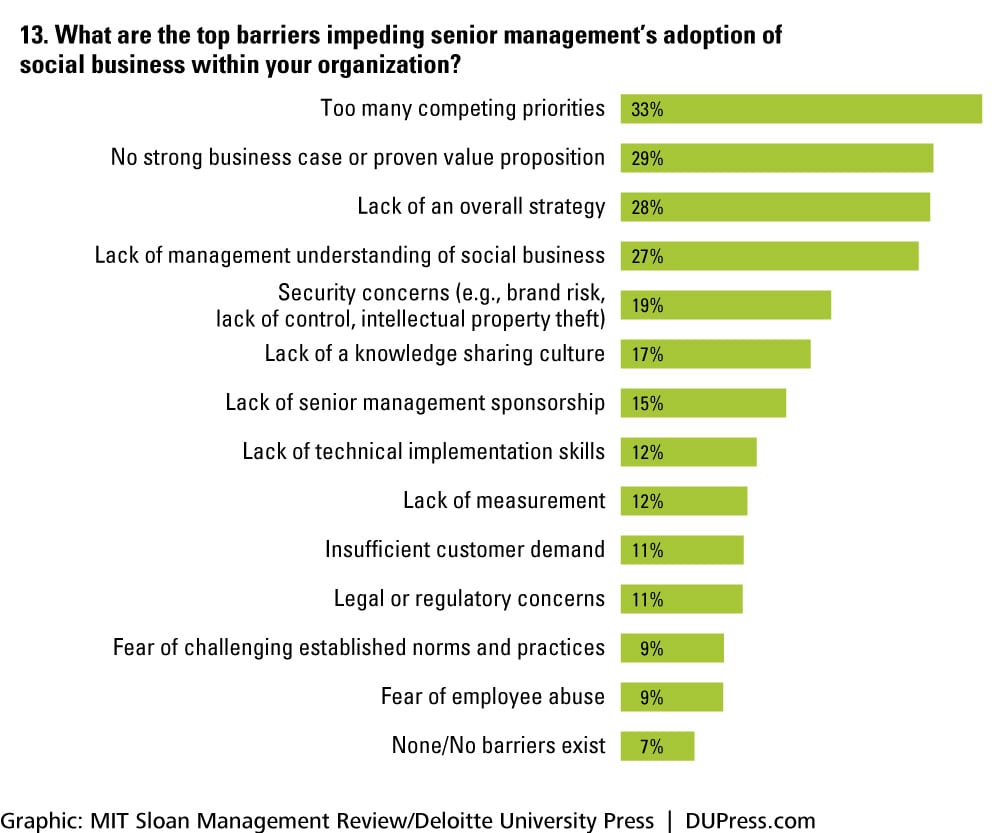

The barriers to social business success remain stubbornly consistent. Although their order of importance shifts from year to year, the top three barriers are the same:

- Too many competing priorities

- No strong business case

- Lack of an overall social business strategy

However, the growing sophistication of social business measurement signals the ultimate dismantling of these barriers. In our first survey in 2011, “don’t measure” was the most common response to measurement questions. Today, companies are increasingly using traffic measures and anecdotes. Companies at the high end of the social business maturity scale are moving beyond traffic measures, and they deploy operating and financial-based measures that show the impact of social business on bottom-line results. (See Figure 3.)

FIGURE 3: COMPANIES USE MULTIPLE METRICS TO DEMONSTRATE THE VALUE OF SOCIAL BUSINESS PROGRAMS

The sophistication of measures continues to advance as well. Blake Chandlee, vice president of global partnerships at Facebook, points out how the social media giant is partnering with a global brand data business to help companies measure the “full loop” of their social media campaigns — everything from identifying audiences and matching them on Facebook to measuring audience response after running a campaign. Businesses can then do more than ask the question, “Should I put a page on Facebook?” Instead, the question becomes how to invest in specific consumer campaigns.

“What” to measure can be just as important as “how.” For example, Mondelēz International, Inc., one of the world’s largest snack food companies (formerly Kraft Foods Inc.) with brands including Oreo, Trident and Wheat Thins, realized that looking narrowly at the impact of Twitter missed the bigger picture of how tweets influence television viewership and thus the impact of TV advertising. “Most organizations look at social media spends as discrete activities and results,” says B. Bonin Bough, vice president of global media and consumer engagement at Mondelēz. His team is responsible for all media, including TV, digital and out-of-home marketing. “We have flipped that idea on its head and look at how social amplifies the bigger pieces of the media ecosystem,” he says. “When we run social and television together, for example, the impact doubles since social channels increase the reach of our core TV video products.”

Carlson-Jagersma at Wells Fargo cautions that measurement for measurement’s sake can diminish the potential impact of social business. “When measuring social, you need to focus on the business question you are trying to answer,” she comments. “These shouldn’t be ‘make or break’ questions about one program or event. It is more about understanding which social efforts will become the glue that makes you a social business.”

Lastly, this year’s survey found that regardless of where a company sits on the social business maturity scale, it is likely to use stories or anecdotes to demonstrate social’s worth. Use cases and the power of narrative continue to have a role, whether social business activities are being used for marketing or other organizational purposes.

2014 Findings: Fueling Social Business Maturity

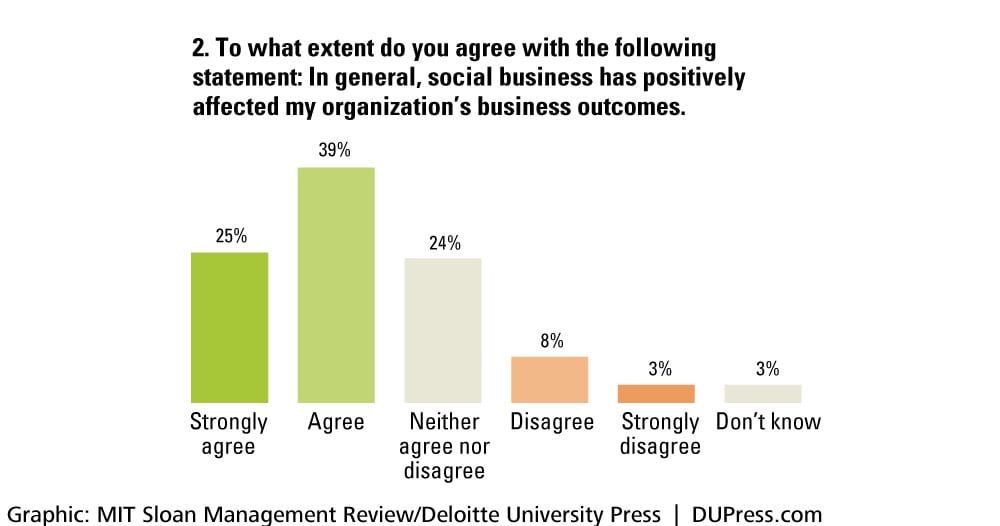

The advance of social business is having a clear impact: 63% of respondents agree or strongly agree that social has had a positive effect on their company’s business outcomes.

T-Mobile USA is a case in point. While monitoring customer conversations on social networks, the company discovered that a major source of customer frustration was the fact that T-Mobile didn’t offer iPhone mobile devices at the time. Losing large numbers of subscribers, T-Mobile moved quickly into action. The company identified at-risk customers using names and the geo-location of their tweets. T-Mobile then tracked these customers in its CRM system to engage them specifically. Before customer contracts expired, T-Mobile marketed to these subscribers in real time, stressing the advantages of T-Mobile. The initiative reduced customer attrition by 50% in only 90 days. T-Mobile executives credited the social business approach with the company’s turnaround during dark days when customers were defecting in droves.

BASF is also meeting business objectives with its social business program. Approaching its 150th year of operation, BASF has approximately 88 global and regional business units and more than 100,000 employees worldwide. Through “connect.BASF,” the company’s global internal collaboration platform launched in 2010, the organization is boosting the productivity of its employees. “After four years, we now have 4,500 communities working together on a wide variety of business topics,” says CheeChin Liew, the company’s enterprise community manager. A globally dispersed team, for example, needed to contract a new vendor. Using connect.BASF, the team eliminated several impediments to productivity that were draining time and resources. A misunderstanding on a conference call, for instance, was quickly identified and resolved in online exchanges, preventing team members from moving in different directions. On-boarding new team members also was able to move very quickly — new members could simply read the project diary instead of taking the time of other team members to get up to speed. The company’s social community leaders estimate that the collaboration platform increases project efficiency by up to 25%.

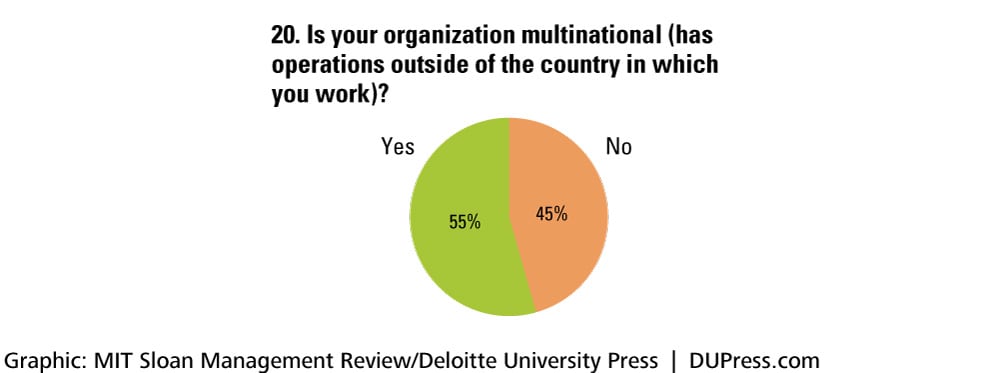

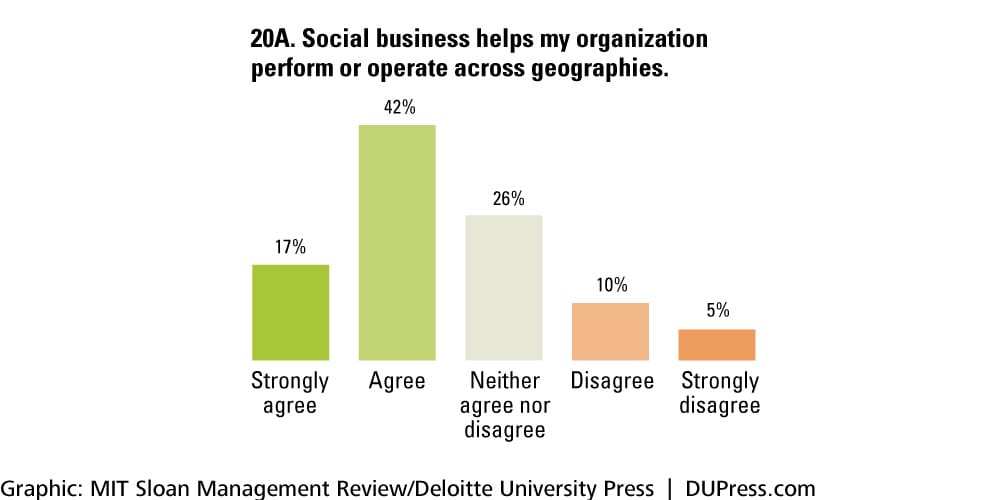

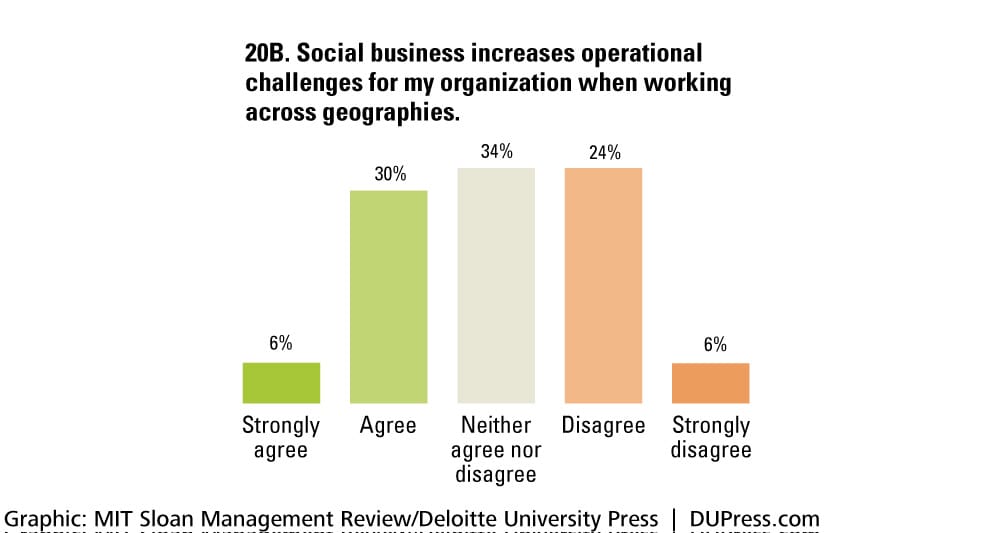

As the BASF example illustrates, social business can have a positive impact on cross-border operations — nearly 60% of respondents who work in multinational companies reported that that was the case for them. Consider a global financial services company we spoke with. Shortly after launching its internal collaboration platform, leaders asked users who they knew at the company and who they considered experts in the online community. The company found that most employees identified experts in the U.S. In response, the organization analyzed its social network and identified champions in different parts of the world to help drive adoption and knowledge sharing in their locales. Through social business, the company elevated expertise from a U.S.-centric view to a global level.

Cross-border collaboration is not without its challenges, however. Although the accuracy of translation software continues to improve, Dion Hinchcliffe, chief strategy officer at the consulting firm Adjuvi, is quick to point out that there are issues beyond language. “Regional culture has a profound impact in how you design social business solutions,” he says. “The solution you develop for Europe won’t fly at all in parts of Asia.” Employees in Germany, for example, are comfortable challenging their superiors in an open forum because German law prohibits using social media postings to evaluate performance. In the U.S. and Asia, that is not at all the case.

We also found that social business continues to play an increasing role in day-to-day decisions. Hearsay Social, a social marketing platform for advisers and sales professionals in regulated industries, is helping financial planning companies identify their clients’ major life events, such as getting married or having children, by looking at what people say on social media. These life events predict the need for investment advice. “People are sharing an incredible amount of detail around personal life events that are very relevant to a financial adviser — such as if they got engaged, bought a house, or are having a baby,” says Gary Liu, vice president of marketing at Hearsay. “Our machine learning algorithm distills those key life events and shows only the relevant signals in a dashboard. The adviser can then congratulate the client on social, but also reach out in the real world at the right time with relevant financial guidance and products for that milestone.”

Similarly, while T-Mobile was monitoring trends in social media conversations, it discovered that mobile customers across the board were fed up with long-term contracts. That insight led T-Mobile to make the bold move to eliminate those contracts.

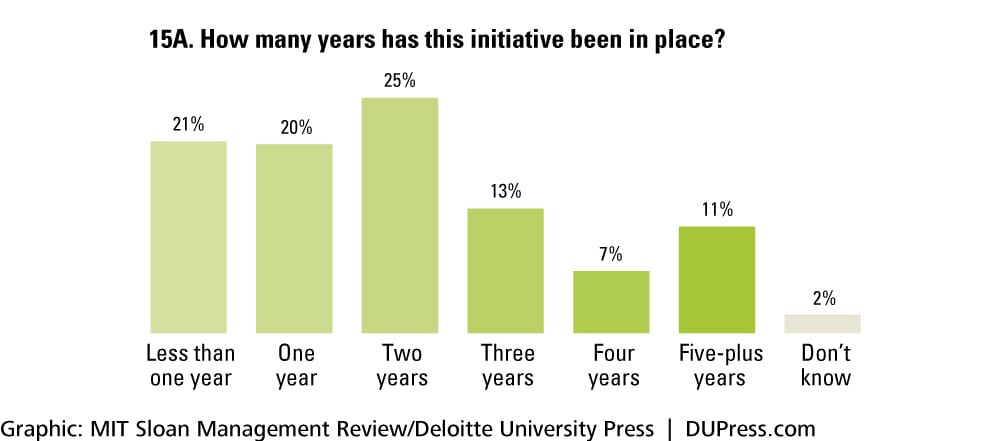

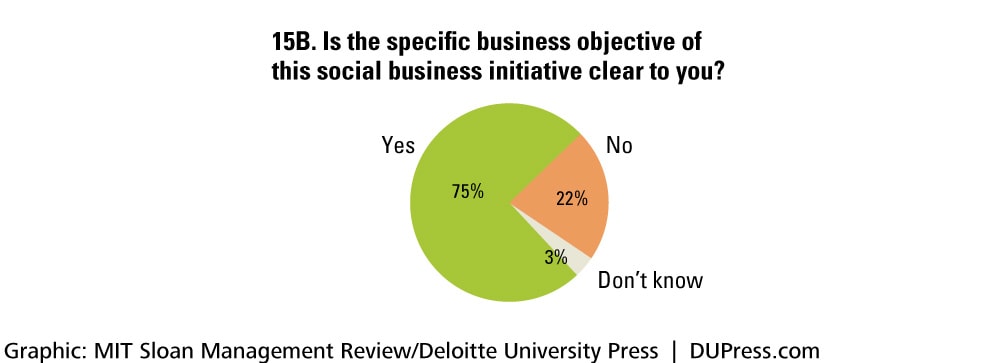

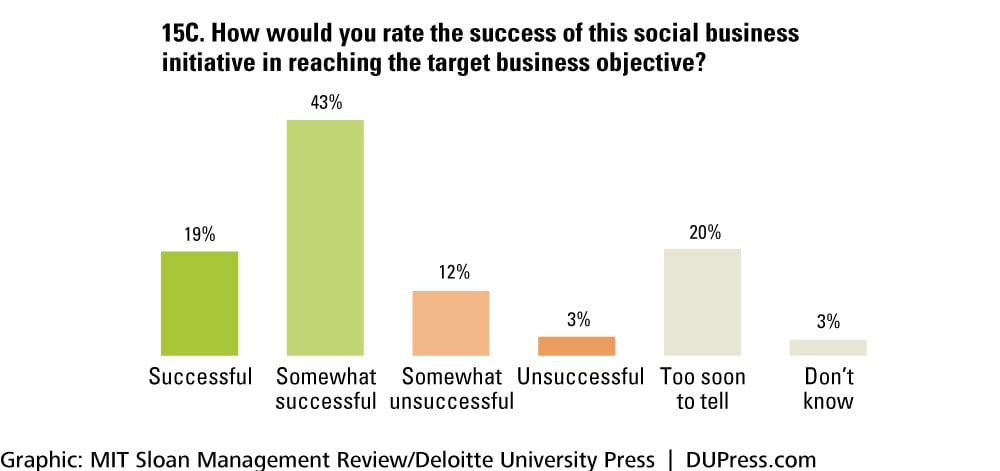

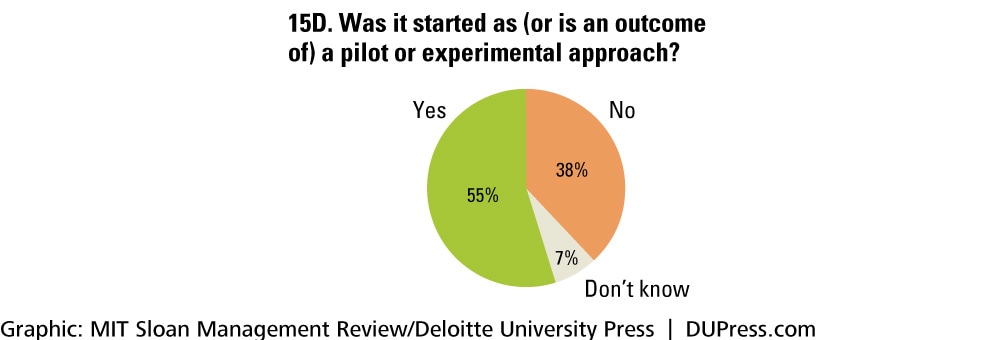

In contrast to predictions by social business skeptics, we found a distinctly optimistic view of the organizational impacts of social business. In 2012, for example, Gartner predicted that between 2013 and 2015, 80% of social business initiatives would fall short of their stated objectives.2 Our survey found that more than 60% of respondents say social business efforts have been successful or somewhat successful at reaching their target business objectives.

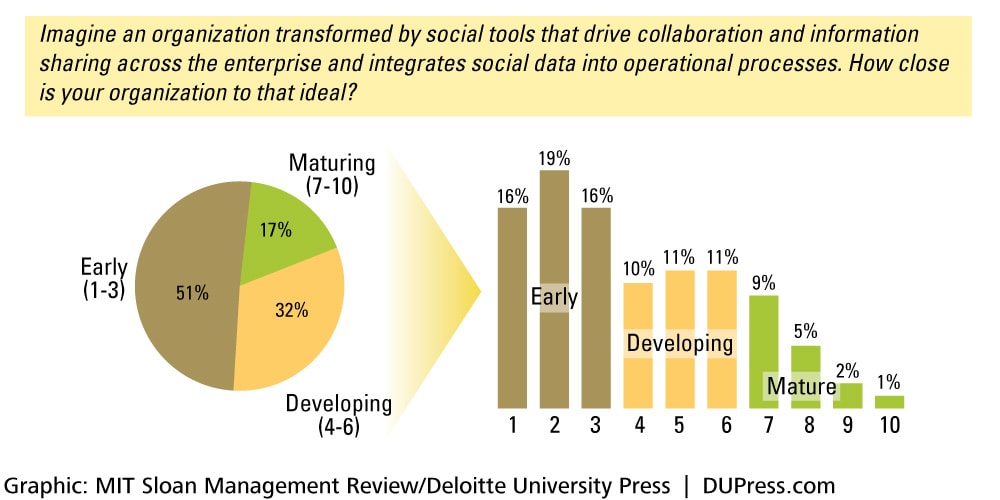

Maturity Links to Results

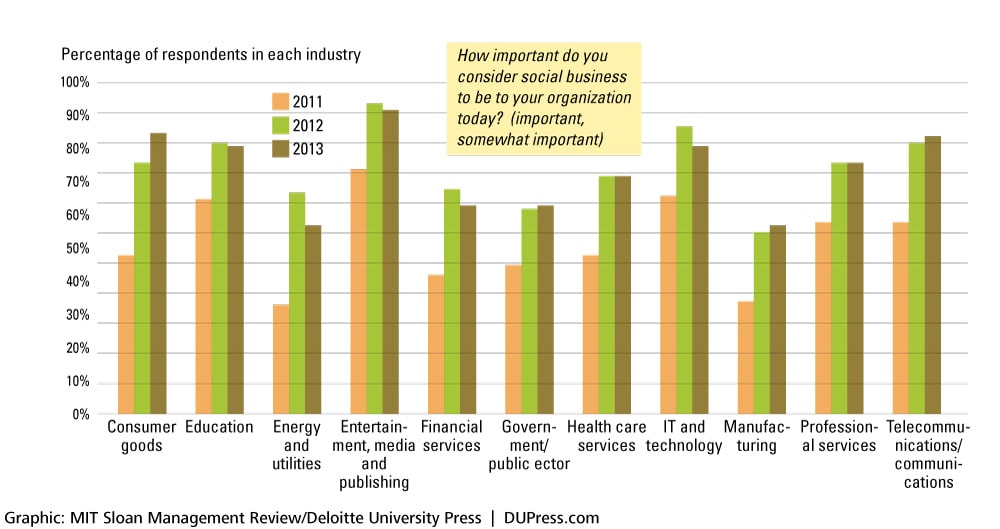

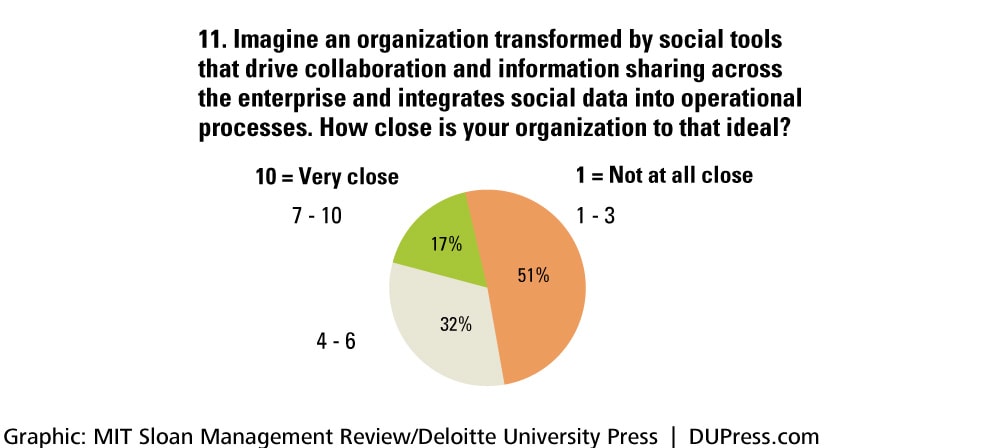

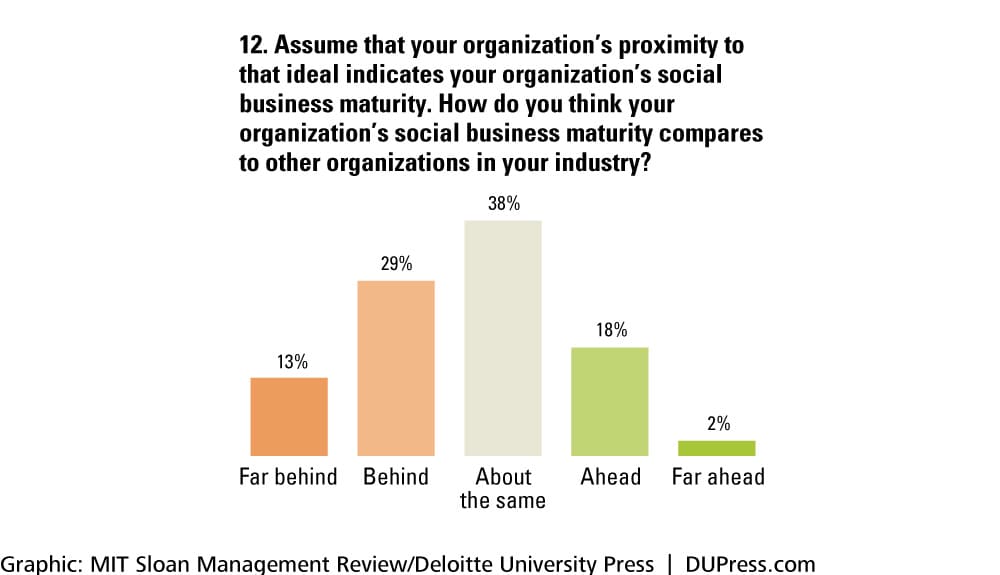

Not all companies have the same ability to create social business value. (See Figure 4, page 10.) Our survey and analysis found that social business maturity is associated with the level of results companies achieve. To assess their organization’s maturity, respondents were asked to imagine a company with ideal social business practices and then compare their own organization to that ideal on a scale from one to ten. (See “About the Research.”)

FIGURE 4: MATURITY LEVEL OF SURVEY RESPONDENT COMPANIES

We found that the higher a respondent rates his or her company on this social maturity scale, the more likely he or she is to report that social business creates real value. (See Figure 5.) We also found that businesses at the top ranks achieve their maturity by focusing on these three primary drivers:3

- Using social business data in decisions

- Embracing a leadership vision premised on the belief that social business can fundamentally change the business

- Moving social business beyond marketing to realize that vision

FIGURE 5: MATURITY TRANSLATES INTO VALUE

Although becoming a mature social business represents a major transformation that lasts several years, our analysis found that the endeavor can move forward in small, incremental steps. Moving up the maturity scale, even one rating point, can lead to better results. The Red Cross, for example, started by addressing sentiment in the blogosphere. Gradually, over nine years, the organization expanded its social business capabilities to identify disasters as they were happening and to manage its trucks. In the remainder of this report, we look at how companies are moving up the maturity scale.

Using Social Data

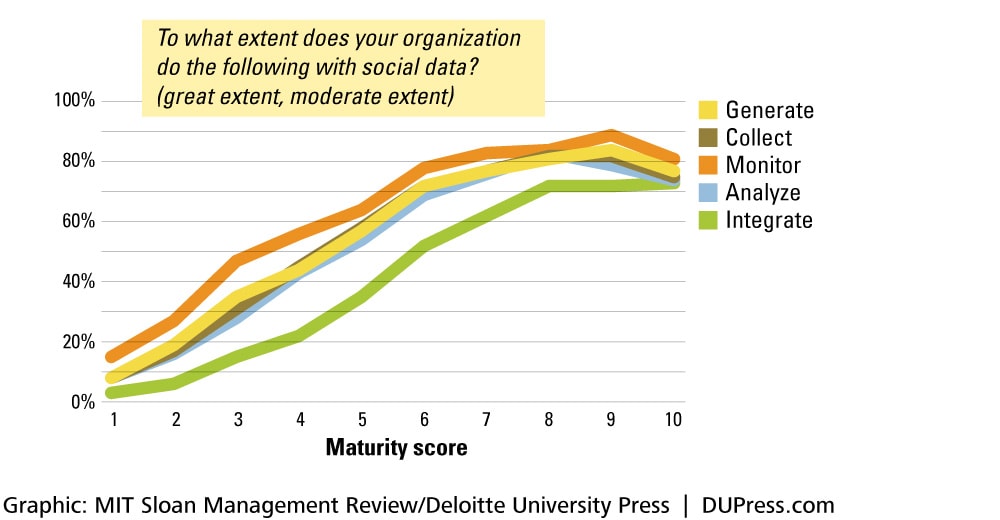

Mature social businesses are dramatically more likely than other companies to report effective use of social business data. Maturing companies are not simply “doing social.” They use the data from their social business initiatives to deliver the desired business value. (See Figure 6.) To achieve results, social media data analysis doesn’t have to be unduly complicated. The key is to use social business data to improve efforts and glean insights that wouldn’t have been visible otherwise.

FIGURE 6: MATURING SOCIAL BUSINESSES USE SOCIAL DATA TO ADDRESS BUSINESS OBJECTIVES

The responses illustrated above reflect the percentage of respondents in each maturity level who said “great or moderate extent” for each social data-related activity. Maturing social businesses are much more likely to integrate social data into operations than early-stage social businesses.

Monitoring Data and Engaging the Social Environment

Monitoring is the foundation of using social business data effectively. Monitoring involves more than real-time tracking, however. Businesses should analyze results over time in order to identify opportunities for change and impact. Wayne St. Amand, former executive vice president of marketing for Crimson Hexagon, a Boston-based social media monitoring and analytics company, tells the story of a speculative analysis it completed for Slime brand tire products. Accessories Marketing, Inc., based in San Luis Obispo, California, sells a line of products to fix flat automobile tires. Through an analysis of the social media data it monitored, the company discovered that bicyclists were talking about using the product to prevent flat tires—revealing new marketing opportunities to promote the product for that all-new use.

Engaging with the social environment is the next step. “After we aggregate social data, we begin using it to improve our targeting,” says Bough at Mondelēz. “Then we come up with interactions for customers after they buy to bring them back into the social fold.” Similarly, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines processes 30,000 to 35,000 messages per week.

It uses heat maps and advanced analytics to track issues by country and peak hour and then engages with airline passengers about those issues. In highly regulated industries, engaging with customers may be extremely challenging, but companies are moving forward nonetheless. For instance, the health care organization Kaiser Permanente worked closely with regulators to create a pilot program where the company could reach out to its members who were expressing concerns and complaints in social communities. Kaiser Permanente engaged with members in real time and directed some to offline grievance and complaints processes when the situation warranted.

Integrating Social Business Data

Analysis of our survey results finds that integrating social data into systems and processes is the most important hallmark of mature social business data use. For example, Facebook is partnering with other companies to help them integrate their data with information from other sources. The social media company combines native data — information people share with Facebook — with online and offline data from brands to generate powerful marketing insights. For instance, a large consumer products company may want to know what kinds of comments specific consumer groups are saying about its products and what television shows they watch. “Being able to target advertising to consumers based on such specific data is much more effective than guessing which ZIP codes your target market lives in,” says Facebook’s Chandlee. “Historically, the industry never had the scale of mass media along with the ability to personalize that scale in the way social media does.”

Kaiser Permanente is exploring the benefits and risks of integrating into a patient’s electronic health record user-generated data sourced from social media. “People share a great deal of information through social media that could be used to improve their health,” says Holly Potter, vice president of brand communication for the company. “We are looking at how to separate the wheat from the chaff and understand what social data predicts specific health outcomes.”

T-Mobile is embarking on a future where social business data is deeply integrated into its operations. According to Melissa French, director of IT marketing solutions and customer experience, “As you move toward being a stronger social business, you need to make sure every customer touch is part of an integrated experience. That means more than just launching a new Twitter handle. It’s about rethinking how you integrate customer information.”

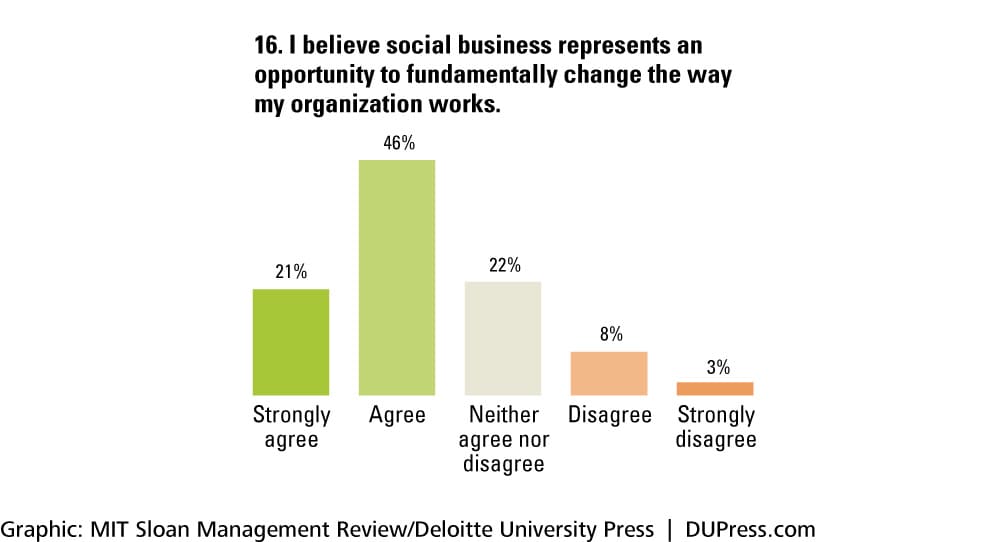

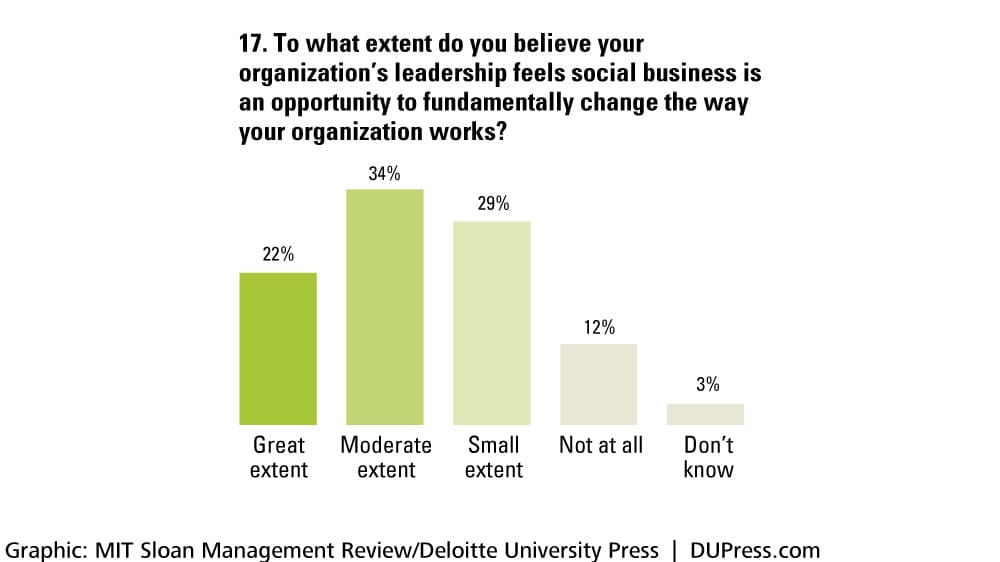

Leadership Vision

Our survey found a powerful relationship between visible senior leadership support and social business maturity. Maturing organizations are led by executives who believe in the potential of social business: 86% of respondents who are board members or C-suite level executives at maturing companies agree or strongly agree that social business represents an opportunity to fundamentally change the way their organization works. This leadership support is clearly visible. More than 90% of respondents from maturing social business organizations feel, to a great or moderate extent, that their leaders believe that social business can fundamentally change the company.

Effective senior management support, however, is a high-wire act that must carefully balance top-down pressures with mechanisms that foster bottom-up creativity and ingenuity. Senior leaders need to fuel grassroots efforts and create a subtle balance between pressure and freedom. At BASF, for example, senior executives began by encouraging social media experiments, especially those that involved different business units. As some of those efforts started to show promise, company leaders announced a mandate to create a global collaboration platform to improve operating efficiency. To harness bottom-up expertise, BASF established an internal “think tank” and charged it with developing the platform.

At BASF today, employees continue to find ways to take social efforts to new levels, and the initiatives often have board-level sponsorship. “Leadership support has been a key success factor since the beginning,” says Cordelia Krooß, senior change management expert at BASF. “Our leadership recognizes the strategic potential of social business and we are seeing senior managers and even board members using connect.BASF to share their thoughts and interact with employees.”

A global financial services company took a similar tack by bringing leaders and employees together to drive social initiatives. The company started with a grassroots effort that identified social business champions who would help build momentum. Then, top management began a drive to address what it found was the company’s biggest challenge — convincing middle managers to jump on board. The balancing act is no easy matter. In many organizations, for example, leaders are not accustomed to everyone in the organization speaking on its behalf. Employees may not be either. Companies should train their workforces in social business and equip them with skills for engaging with the public.

Leaders should also be cognizant of cultural differences. John Glaser, CEO of health services at Siemens Healthcare, points out that cultures have established norms of leadership behavior. In some cultures, such as the U.S., leaders are expected to engage. In others, such as Germany and many parts of Asia, title is important and sets a different set of expectations and communication parameters. “You have to understand the nuances of how leadership is defined in different cultures,” says Glaser.

Finally, when senior leaders use social media themselves, it does reinforce their commitment. However, using it heavily isn’t a requisite. At the financial services company, for example, senior management uses social media simply to complement other communication forums such as chat following the CEO’s town hall meetings.

Perhaps the most important gesture is articulating the importance of social business to the company’s strategy and then understanding how to step back. As Martijn van der Zee, senior vice president for e-commerce at KLM, recalls, “Our CEO told us he didn’t care how we went about building social business capability. We just needed to organize, fund and support it.”

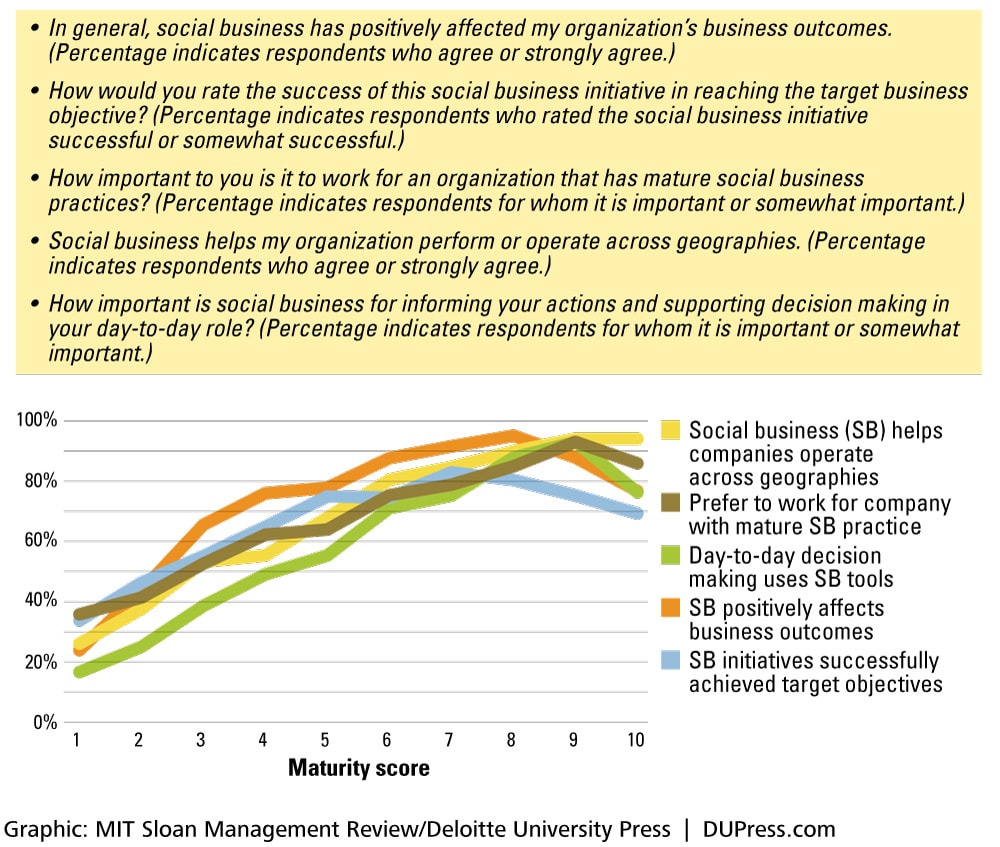

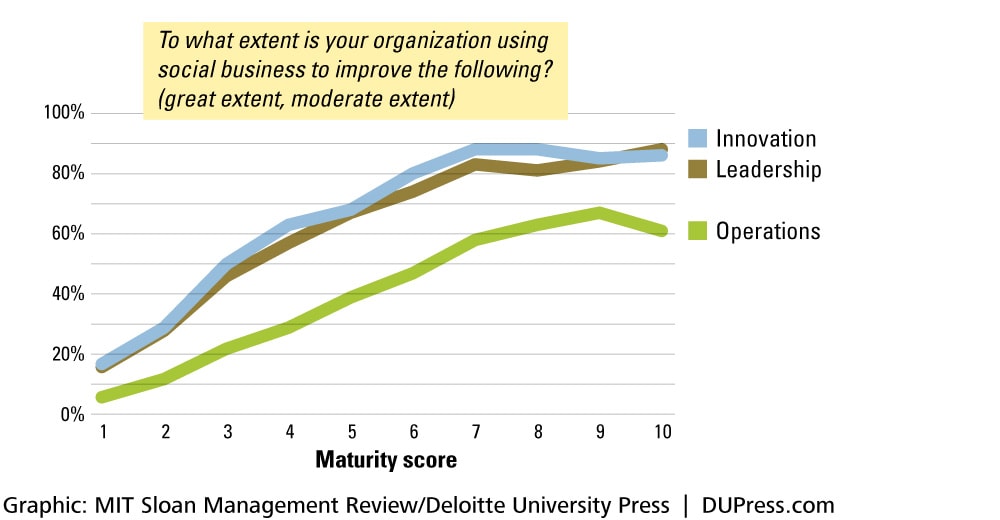

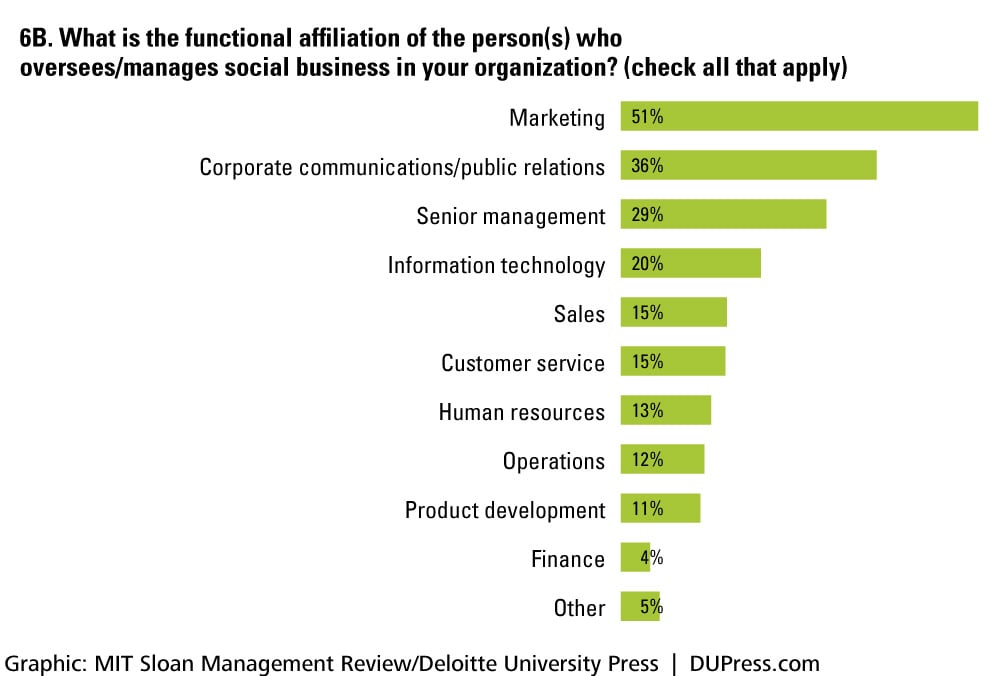

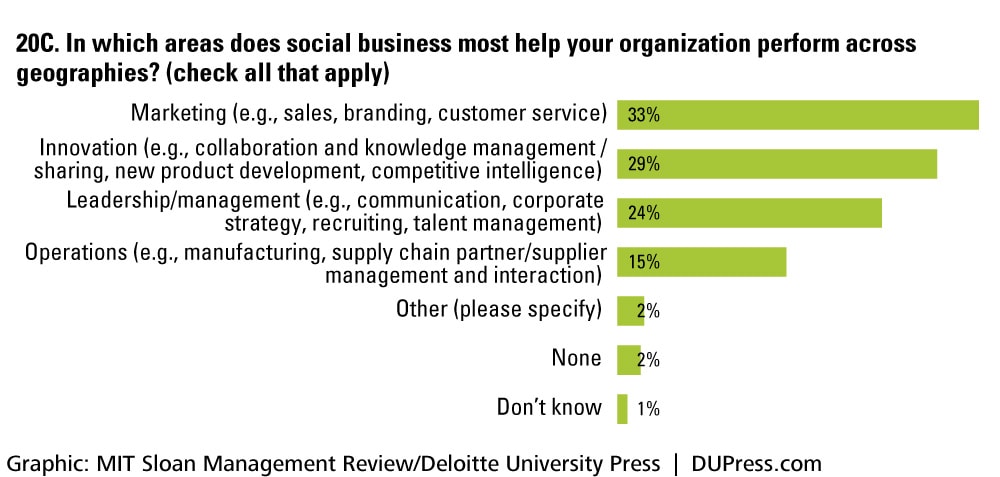

Moving Beyond Marketing

Wendy Harman began her tenure at the Red Cross by helping the organization use social business for marketing. Today she is leveraging social business to change how the Red Cross operates. Our survey found that maturing social businesses are on the same track. Although marketing is a critical component of creating social business value, the story doesn’t end there. In the first year of our study, we created the MILO framework to track the development of social business across the enterprise: how companies are using social business to improve marketing, innovation, leadership and operations. (See Figure 7.) This year, we found that mature social businesses are moving beyond marketing in their quest for social business impact. (See Figure 8.)

FIGURE 7: SOCIAL BUSINESS BENEFITS EXTEND ACROSS THE ENTERPRISE

FIGURE 8: MATURING SOCIAL BUSINESSES ARE MORE SOCIAL ACROSS THE ENTERPRISE

To create value with social business, maturing social businesses are moving beyond marketing, particularly in innovation and leadership. However, there is still opportunity even for maturing businesses to create more value by integrating social into operations.

Spurring Innovation

New ideas abound in the minds of employees. The challenge is bringing them to the fore so that company leaders can assess and act on them. Companies such as the LEGO Group, IBM and SAP were early pioneers of using social to bring these ideas to the surface.4 Each year, more companies are turning to social business to help bolster innovation.

AT&T Inc., for example, has developed a sizable internal crowdsourcing program, including company executives acting as venture capitalists. Launched in 2009, The Innovation Pipeline (TIP) currently has more than 130,000 members from all 50 U.S. states and 54 countries. During a TIP “season,” which lasts about three months, employees submit, vote on and discuss ideas. At the end of each TIP season, the top ideas — based on votes, comments and adviser approval — are selected for presentation to AT&T senior executives.

After a brief incubation period, founders of the top ideas create proposals and develop business cases, and then present their ideas to AT&T senior executives. These executives have money to fund the ideas of their choice. Successful founders leave with funding and the green light to develop their ideas. These ideas are eligible for a second incubation period in which the ideas move from prototype to production, and toward deployment to customers.

To date, TIP has produced more than 28,000 ideas. The program has produced more than 75 projects for development and allocated $44 million to fund ideas ranging from customer service enhancements to new technology offerings. “We believe this is one of the largest internal crowdsourcing efforts on the planet, if not the largest,” says Elizabeth Hitchcock, director of strategy and innovation for AT&T Business Solutions.

MITRE is using social business to spur innovation among its partners. MITRE is a nonprofit organization that operates federally funded research and development centers sponsored by U.S. agencies, including the Department of Defense, the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Homeland Security and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fostering knowledge exchange within and among the research centers is a chief component of its mission.

MITRE has established several communities to help government agencies address complex questions, such as controlling costs. The Department of Defense, for example, needed to understand the expenses involved in building a new testing and evaluation facility. Within 48 hours, the department had detailed information and recommendations from other agencies that had embarked on similar projects.

Similarly, a research center funded by the Department of Homeland Security focused on improvements in first-response organizations such as state and local police. The online exchange drew hundreds of members of first-responder organizations who were able to share lessons learned. “It’s not very often that a state trooper from one state such as Kansas can share ideas with one from, say, Washington State,” says Donna Cuomo, associate director of knowledge and collaboration systems for MITRE. “While the actual exchanges are sensitive, the collaboration platform’s ease of use both enabled such exchanges and made them more timely.”

Leading and Developing Talent

Talent has been appearing on lists of top CEO concerns for years.5 It is emerging as a primary source of competitive advantage and, as a result, companies are doubling down their talent management efforts. At the same time, social business is becoming a powerful tool to bolster recruitment and employee development.

The United Services Automobile Association (USAA) is a case in point. Founded in 1922, USAA is a diversified insurance and financial services company that caters to individuals and families that serve or have served in the U.S. armed forces. In 2013, the organization had more than 10 million members.

USAA uses several social media sites, including LinkedIn and Facebook, to build up its image as an employer. Using rich media, including video and photos, the company paints a vivid picture of the advantages of a USAA career and the experience of working there. Social media is also accelerating the identification of top prospects. Renee Horne, assistant vice president of social business for USAA, recalls posting an open position to her LinkedIn group. Two hours later, a preferred candidate popped up.

USAA also uses social business to on-board and retain talent. The organization recently launched Impact, a community targeted at the company’s Millennials. As Horne describes it, employees can reach out and “pick the greatest brains and minds at USAA to get ideas, solve business problems or gain coaching on how to develop their careers.” As an organization serving armed forces personnel and their families, helping recent veterans who have joined the company is critical. To smooth their transition from the military, USAA has established several social business communities that provide mentoring. “Professional growth and development communities in our organization are growing,” says Horne. “The participation and engagement in these groups is large.”

Integrating into Operations

By integrating social business into operations, companies can gain a competitive edge by meeting customer needs in new ways. KLM is a prime example. Using Facebook and Twitter, the airline has replaced the need for elite customers to phone call centers to book upgrades. These customers can now request and pay for upgrades through social media sites and receive a new boarding pass within minutes.

KLM also uses social business to improve its lost-and-found service. When passengers leave an item on a plane and don’t realize it until they have cleared customs or gone past security, it’s usually a difficult or impossible task to track the item down. Now, passengers can report a lost item through Facebook and Twitter, and KLM picks up the message and advises personnel to check planes, lounges and boarding areas. “I can honestly say that all of our initiatives are aimed at integrating social into our business,” says KLM’s van der Zee. “And not because it’s a gimmick. It really it gives us an edge over other airlines.”

The emergence of new technologies that combine enterprise social data with information from other sources, such as ERP systems, is providing companies with a clear line of sight into their operations and how collaboration can foster improvements. Executives at a Silicon Valley company, for example, were concerned when they discovered that only 200 of 6,000 deals with external partners had officially gone through the company’s legal department. When delving into their internal social business platform, they found a vibrant web of experts in the organization who were regularly working with one another to vet proposed arrangements. Using collaboration tools, these employees could find people with specific expertise and, equally important, time to help review the partner deal.6

Avaya, a provider of business collaboration and communication software, is another example of a company that uses social business to improve customer service. For instance, a sales associate confronted with a customer need that is an exception to standard procedures can search conversations on the company’s internal social business platform. That person can see if other associates had the same issue and, if they did, how it was resolved. If there isn’t a relevant discussion, the associate can create one, which saves considerable time by eliminating the scramble of finding someone with an answer through meetings and copious email exchanges.7

Finally, social business has the potential to transform government operations. David Bray, CIO of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), notes that by offering an open source, freely available app, U.S. mobile consumers can choose to opt-in and share anonymized data to help inform policy decisions. “The FCC Speed Test App was ranked number four on the iOS store in terms of most downloads for a while, right behind Google Chrome, a first for any government mobile app,” says Bray. “The IT vision is that individuals and institutions can choose to share anonymized data in a rapid fashion with a trusted broker to inform evidence-based policy making decisions.”

Moving social business beyond marketing creates a virtuous cycle that reinforces social as a source of business transformation. The data from each initiative informs which will have the greatest impact, and how. That knowledge arms leaders with insights into new potential initiatives. When the company launches those, the virtuous cycle begins anew.

Conclusion: Moving Up the Maturity Scale

To wrap up our third annual report, we share some advice that can help business leaders take the next steps toward increasing the social business maturity of their organizations. These insights come from our survey results, the interviews we conducted, the literature we read and robust debates we have had about what insights would be most helpful.

The most pertinent is the executive “aha.” Many business leaders we spoke with describe a moment during social media experiments when it became clear that the relationships among customers, business partners and employees had fundamentally changed. In this year’s research, we found the “aha” underlying social business efforts in everything from retrieving a lost toy on a plane to mobilizing communities to respond to disasters. Increasingly, corporate leaders realize that social business is changing the way organizations operate and the experiences they provide to their customers and constituents.

The foundation of that realization is a steadfast belief that social can effectively transform an organization. Driven by that understanding, socially maturing businesses are using social data in decisions and moving social business efforts beyond marketing. But perhaps most important, we also found that social business transformations happen in incremental steps, and each step can lead to tangible business value. To help organizations map their steps to social business maturity, we encourage leaders to ask these questions:

Is the company using measurement and data to understand social business value? Social business efforts need to drive tangible business outcomes. While it will take some effort, maturing social businesses keep moving beyond “clicks” and “likes.” They are using financial and operational metrics to understand the full impact of social business. T-Mobile, for example, combined social media with analytics to discover that customers hated contracts. Kaiser Permanente is exploring the risks and benefits of embedding social data into electronic medical records and using analytics to understand what data predict health outcomes.

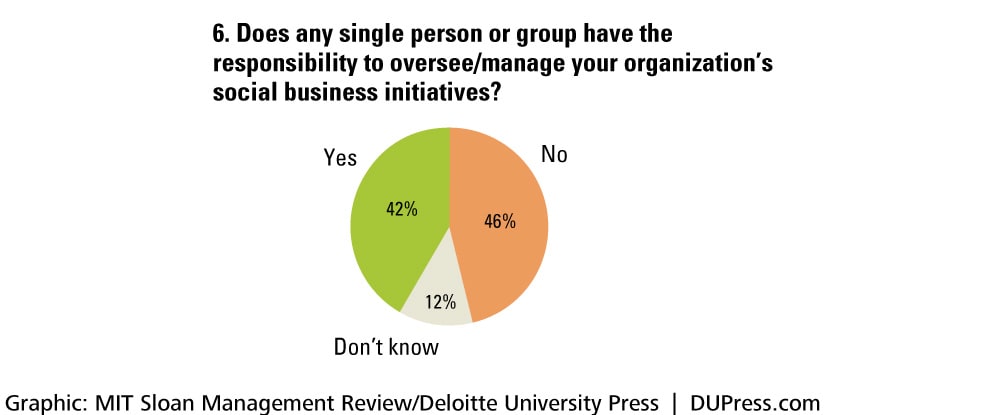

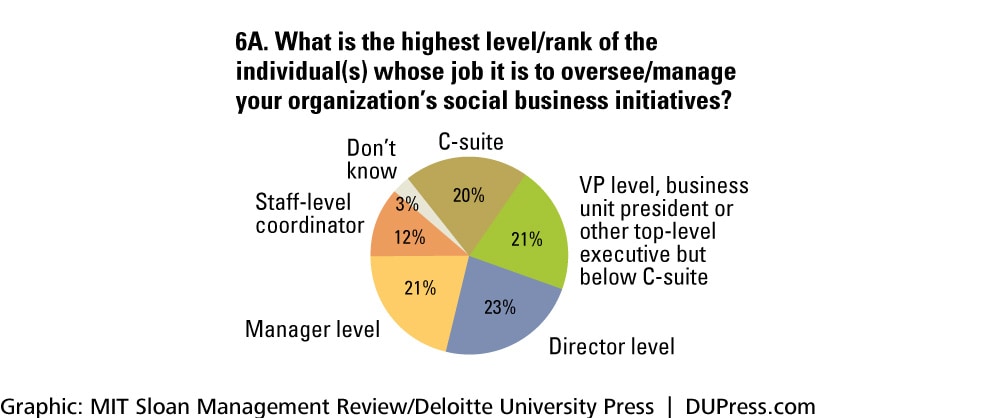

Are company leaders on the same page? C-suite alignment is critical if social business is to permeate the organization. While experimentation and grassroots efforts are important, company leaders need to align and integrate these efforts. Leaders provide the needed resources to support the transformation and communicate its importance to the organization. For example, are social monitoring tools and data sets linked to CRM and case management tools? Is there a focal point for the company’s social business efforts? Are the CMO, CIO and COO working together? Many executives we interviewed felt empowered to work across organizational boundaries. Is there someone in the organization driving that empowerment?

Is social being used to recruit and retain talent and help it flourish? Our survey found that employees across generations want to work for companies that excel at social business. Increasingly, organizations are encouraging employees to become brand ambassadors by using social in everything from building customer relationships to recruiting new talent. To serve as effective brand ambassadors, employees need clear guidelines that delineate what they can and can’t do. As prospective employees turn to social media to explore a company’s culture and the experience of working there, businesses need to put their best social foot forward.

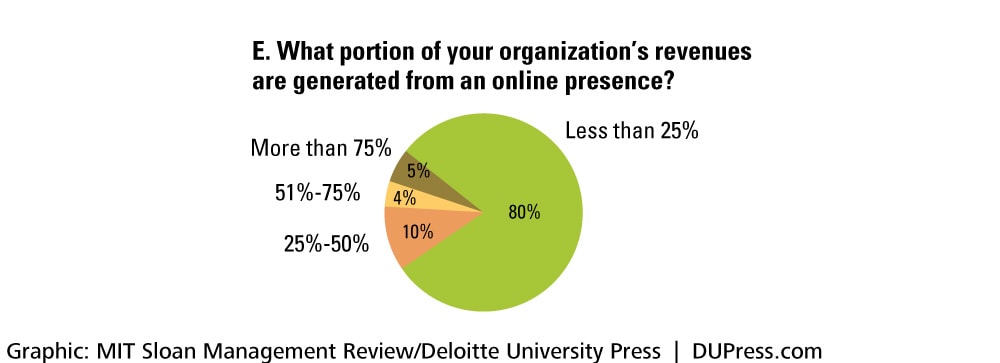

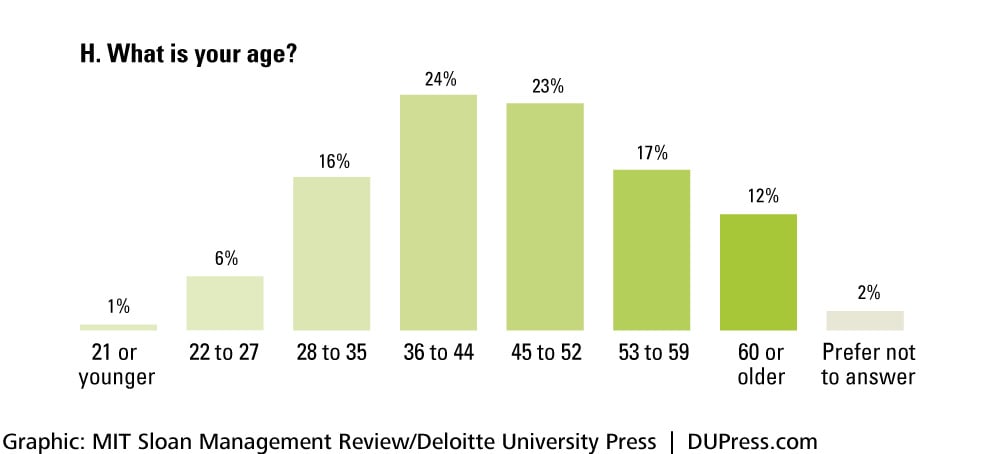

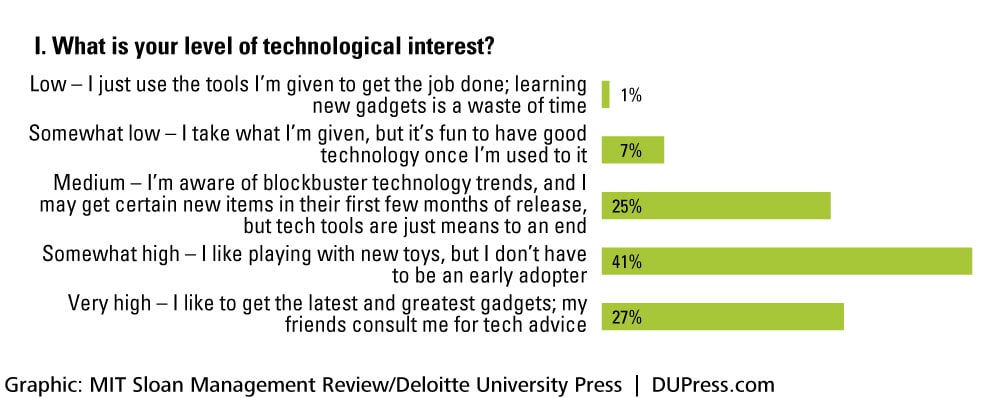

The Survey: Questions and Responses

Results from the 2013 Social Business Global Executive Survey

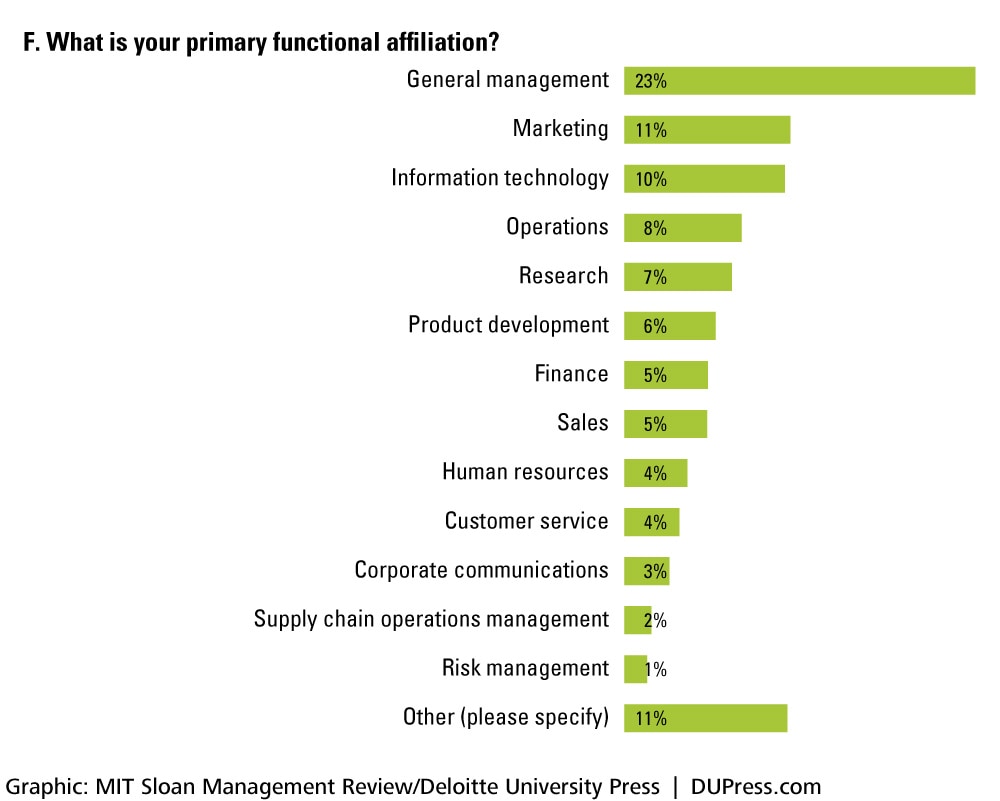

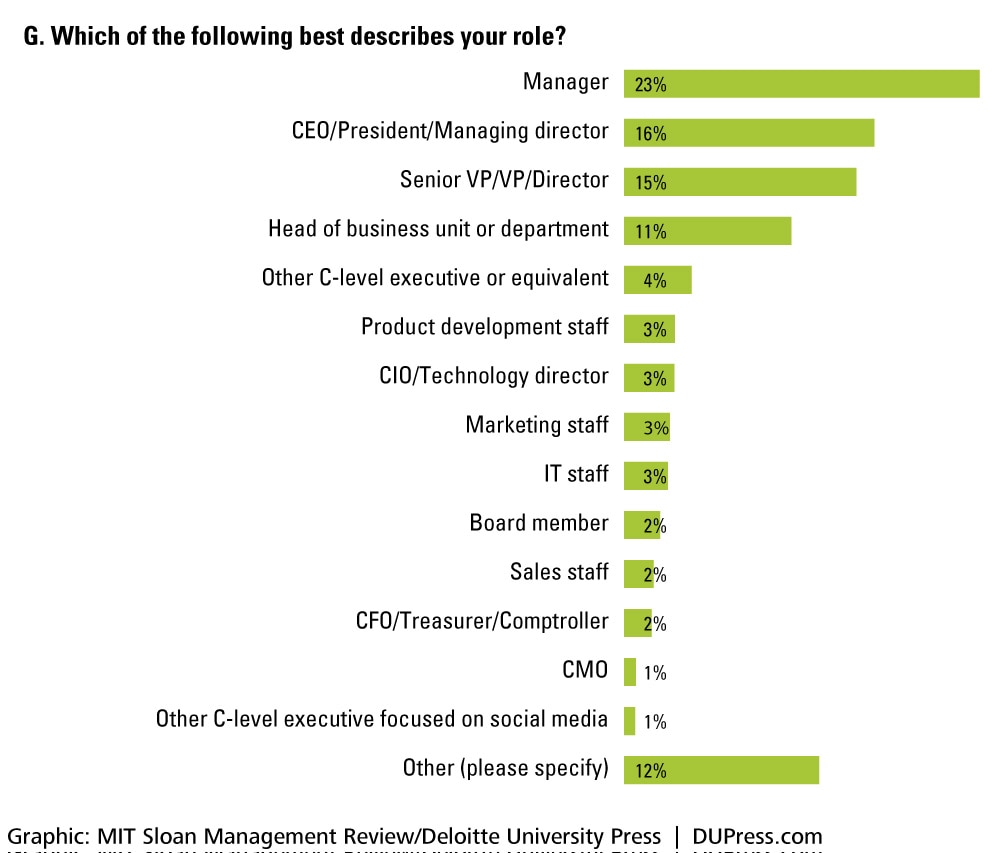

About the Research

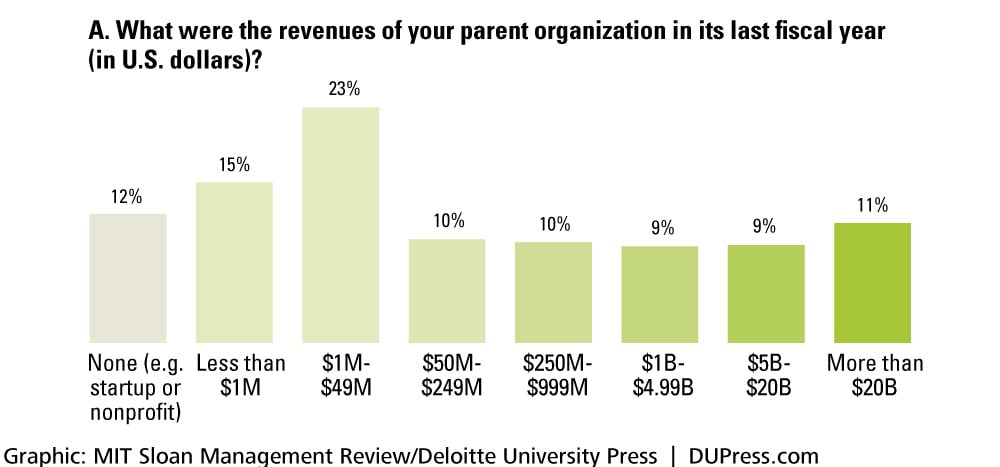

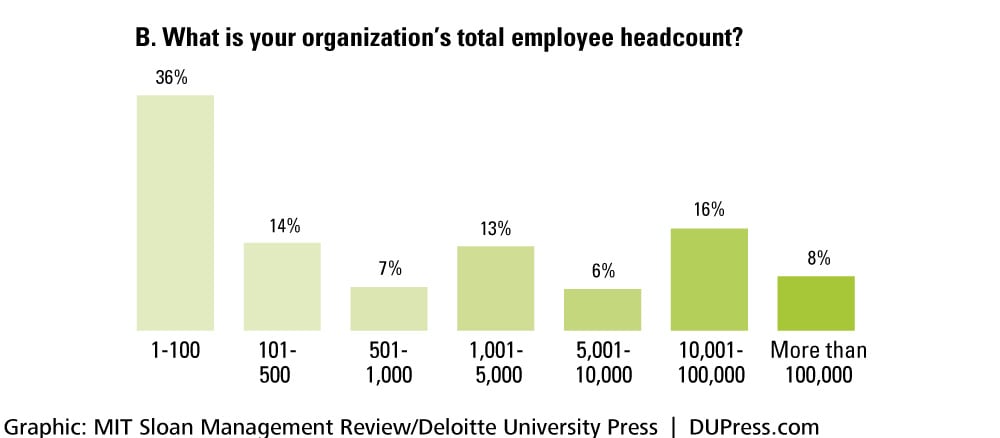

To understand the challenges and opportunities associated with the use of social business, MIT Sloan Management Review, in collaboration with Deloitte, has been conducting annual surveys of business executives, managers and analysts from organizations around the world. Three surveys have been conducted since 2011 totaling more than 10,000 responses. Annual survey samples are drawn from a number of sources, including MIT alumni, MIT Sloan Management Review subscribers, Deloitte Dbriefs webcast subscribers and other interested parties. In addition, 79 subject matter experts and leaders from 69 organizations globally have been interviewed. Their insights contribute to a richer understanding of the data.

The most recent survey was conducted in the fall of 2013 and included responses from 4,803 business executives, managers and analysts. The survey captured insights from individuals in 109 countries and 26 industries and involved organizations of a broad range of sizes. As part of this most recent survey, we asked respondents to rate on a scale of 1 to 10 the maturity of their organization’s social business practices by asking: “Imagine an organization transformed by social tools that drive collaboration and information sharing across the enterprise and integrate social data into operational processes. How close is your company to achieving that ideal? (1 = ‘Not at all close’ and 10 = ‘Very close’).” Organizations whose respondents rated their organization’s social business practices as 1-3 were categorized as “early”; 4-6 were categorized as “developing”; and 7-10 were categorized as “maturing.”