Ripple effects: Why water is a CFO issue has been saved

Ripple effects: Why water is a CFO issue A CFO Insights article

03 August 2012

Growing global demand for fresh water could disrupt business and supply chain operations and lead to higher costs and prices of commodity products—which should put water scarcity on the CFO’s radar.

Much of the world is parched. In July 2012, just under 56 percent of the contiguous United States was experiencing drought conditions, the most extensive area in the 12-year history of the US Drought Monitor.1 Elsewhere, drought-like conditions may be in store for India and Pakistan, where monsoon rains have been significantly lower than normal;2 parts of the Korean Peninsula continue to endure the worst drought in more than a century;3 and dryness in Russia is threatening vital wheat crops in that country.4

Much of the world is parched. In July 2012, just under 56 percent of the contiguous United States was experiencing drought conditions, the most extensive area in the 12-year history of the US Drought Monitor.1 Elsewhere, drought-like conditions may be in store for India and Pakistan, where monsoon rains have been significantly lower than normal;2 parts of the Korean Peninsula continue to endure the worst drought in more than a century;3 and dryness in Russia is threatening vital wheat crops in that country.4

Basically, water, the once plentiful resource, is growing scarcer. And that scarcity is a finance issue—one that has the potential to disrupt business and supply chain operations, lead to increased costs, and increase the price of commodity products. Part of the problem is that the demand for fresh water has doubled over the past 50 years.5 Moreover, it is likely that things may get worse. So much worse that it is projected that about half of the world’s population may experience water scarcity by 2030.6

In this issue of CFO Insights, we explore the reasons behind water scarcity, the risks associated with the growing lack of water, and why water availability is a CFO issue.

The big thirst

In his book Corporate Water Strategies,7 William Sarni makes the case for how precarious water really is. While there is no less water globally—water is neither created nor destroyed—there are a number of macroeconomic reasons why there is increased competition for this finite resource:

Increased population. There will be an estimated 8 billion people occupying the planet by 2030.8 As a result, more people will need water.

Economic growth. The World Bank estimates 6 percent growth in developing countries and 2.7 percent growth in developed countries over the next 20 years.9 To achieve that, however, requires clean, adequate sources of water. And while roughly 70 percent of global water use is associated with the agricultural sector (a critical input to the food and beverage sectors),10 other sectors, such as power and apparel and even semiconductors, also require large quantities of water to operate.

Rise of the middle class. As people move up the economic ladder, they tend to consume more—from energy to food to discretionary items—and those things require water to produce. Specifically on changing diets, moving from a diet consisting primarily of grains and vegetables to one that includes higher amounts of protein requires more water throughout the extended supply chain.11

Basically, water, the once plentiful resource, is growing scarcer. And that scarcity is a finance issue—one that has the potential to disrupt business and supply chain operations, lead to increased costs, and increase the price of commodity products.

Increased urbanization. About half of the planet’s population now lives in urban settings. In China alone, it is estimated that 1 billion of its people will live in urban areas by 2050, making it the largest concentration worldwide.12 As people migrate to cities, they typically use more water, but that does not necessarily mean that there will be an adequate supply of water in that area. Plus, such a concentration of people may lead to competition for water resources among industrial, domestic, and ecosystems needs.

Water risks

All of those factors are converging to make water an increasingly scarce resource—at a time when demand has never been greater. The implications for companies and their CFOs are wide and varied. For example, if a company has a growth strategy that includes emerging markets such as India, China, or Africa, then they are facing increasing water scarcity. Even if their supply chains reside in one of those regions, there are real risks imposed by not having enough water to grow crops or manufacture products.

The effects are already being felt. According to the Carbon Disclosure Project’s (CDP’s) 2011 Water Disclosure Report, roughly 40 percent of companies said they have experienced water-related risks in the last five years.13 In addition, water-related risks with the potential to have an impact now or within five years accounted for 64 percent of all risks reported in direct operations and 66 percent in the supply chain.14

The risks fall into three major buckets:

- Physical scarcity. The potential scarcity of water has real implications for operational continuity. For example, discontinuous water availability for a beverage company can disrupt the manufacturing process and lead to revenue loss; lack of water for power plant cooling can disrupt energy generation; and inadequate access to water can preclude or delay the development of shale gas. CFOs need to ask, “Do I have enough water of the right quality and quantity when I need it and where I need it?” In water-scarce areas or areas that are being stressed, the lack of water has the ability to not only disrupt business, but to shut it down for some time until reliable, sustainable access to water can be restored.

- Regulatory risks. There has been an increase in water regulations globally due to the recognition that there really is no substitute for water. In Australia and South Africa, for example, changes in public policy and pricing have been implemented to address the need for water for agricultural, commercial, and domestic needs (see sidebar, “Don’t confuse water price with business value”). For CFOs, the questions that should be asked include “What water-related regulations are changing and/or becoming more stringent?” Certain regulations could increase operating costs and trigger an allocation scheme that precludes the acquisition of water during periods of drought or decreased availability.

- Reputational risk. Investors and other stakeholders care about water. There are a number of case studies where businesses were negatively impacted because stakeholders within a watershed believed that the company was not operating in a responsible manner with respect to water use. Even the perception of extracting water to the detriment of other stakeholders within the watershed is a problem in a world where almost anyone leveraging social media can impact your social license to operate.

There are other risks associated with water because of its interrelationship with energy. You can’t generate energy without water, and you can’t treat and deliver adequate water supplies without energy. To meet the projected 14 percent increase in US energy demand between 2008 and 2035 will require an enormous increase in freshwater consumption.15 It is a global problem, however. A recent study, for example, predicted that thermoelectric power generating capacity in Europe would decrease 6–19 percent between 2031 and 2060 due to the lack of cooling water for power plants.16

Don’t confuse water price with business value

Water may be essentially “noise” on a profit and loss statement. But that may be about to change.

While the price of water is extremely low, it rose an average of 18 percent between 2010 and 2012 in the 30 US cities tracked by the NGO Circle of Blue.18 In addition, several US states are moving toward tiered pricing, where water prices increase as water use increases. And several cities, including Las Vegas, have put new “fixed” fees in place. These are charges that are paid every month, no matter how much water is consumed.

Different countries have taken steps to restructure water pricing in response to persistent droughts. Australia is an excellent example of how public policy and pricing have changed to address increased water scarcity and persistent droughts. The pricing reforms, which include changing tariffs to signal efficient water use, have led to reduced consumption in urban areas.

For CFOs, now may be a good time to include water in everyday risk assessments. After all, water may be free—up until the time that it’s not available. And then you have a problem.

Why water stewardship is a CFO issue

Preparing for water scarcity starts with understanding your water use across your value chain and then understanding what risks and opportunities that use creates. That means determining how much water you’re using through direct operations and across your value chain (i.e., through the entire supply chain, product use, and product end of life), and then figuring out where geographically you are using that water. Water availability may be a global problem, but it translates into local action because the fundamental building block for water is the watershed.

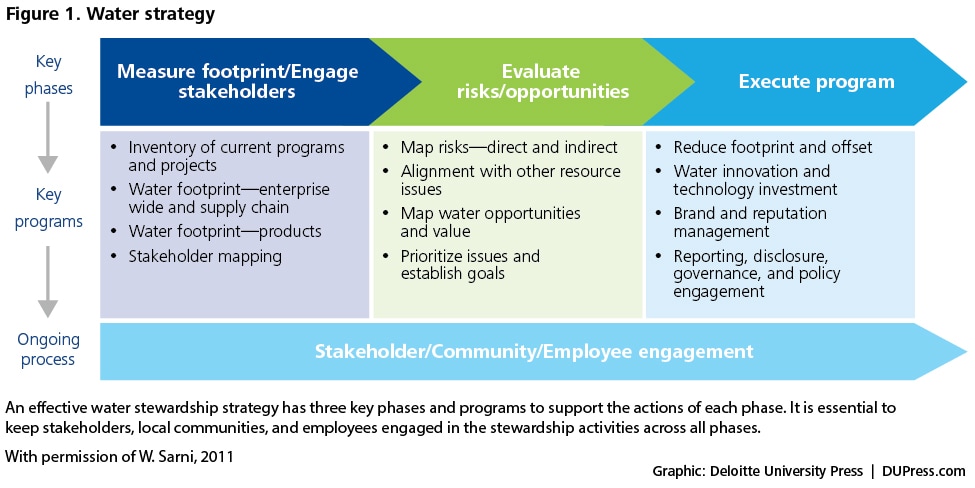

Determining usage is a major component of a water strategy (see figure 1). Water footprinting, which involves determining the volume of water used to produce a specific product within a specific geographic location, is still in its early stages, but methodologies are beginning to emerge, such as the one developed by the Water Footprint Network (waterfootprint.org). In addition, risk mapping can be gauged by leveraging sophisticated risk tools and running analytics on the data. Publicly available risk mapping tools and methodologies, such as those offered by various non-governmental organizations (NGOs), allow you to get started; other, more sophisticated tools enable risk to be readily identified and prioritized for mitigation strategies.17 And part of the exercise is calculating the business value at risk, which essentially rolls up the physical risks, regulatory risks, and reputational risks to come up with a dollar value.

Based on that analysis, companies can decide what to do in order to decrease their water risk. The obvious one is improving efficiency—trying to run your business with less water or even no water at all. Another is to embrace “collective action”—engaging stakeholders to make reasonably certain that everyone has water when and where they need it.

Other specific processes demand water evaluation. Take the process of deciding where various operations and facilities should be located. Some companies understand very well quantitatively if a particular location has the right quantity and quality of water. The semiconductor industry, for example, uses something called ultrapure water that has to be of very specific quality, for use in processing semiconductor chips. Other companies may have to make the decision that it is easier to manufacture the product and ship it to a water-scarce area than to try and deal with the issues of water scarcity in that area.

There should also be a water component in M&A due diligence in the consumer products industry, among others. When acquiring a company, you should know what the target’s water risk profile looks like. In fact, water should be managed like any traditional risk—understand what the risk looks like and value it accordingly.

No treading allowed

The predictions about water are not all dire. There are certain opportunities associated with managing the risks associated with water. For example, there are cost savings associated with reducing water consumption, particularly when energy and water use are viewed together in an integrated energy and water strategy. Water scarcity is also driving innovation—and, as a result, business opportunities—in operational models, product development, and market entry.

For CFOs in any business, the time to create a water stewardship strategy is before you need one. Among the rewards of early action can be enhanced brand value, a head start on water risk mitigation, greater confidence in your license to operate in specific markets, and an added measure of security around the prospects for business continuity in what may become an increasingly unpredictable environment. Given that unpredictability, it behooves CFOs to prepare for water scarcity now and reduce the ripple effects.