Bridge across uncertainty How crisis leadership with a human focus can support business resilience

18 minute read

19 August 2020

Stress overload can impact work and organizational success. However, with planning and human-centered responses, organizations can help build resilience among the workforce and enable them to adapt positively with the business.

Introduction: Contextualizing stress in times of crisis

The root causes of a crisis are often beyond our control, which can make stress—and its effect on the brain and body—more intense. However, people are typically not left with permanent psychological or physical damage; nor need crises define them in a negative way. By mitigating stress and building resilience, people can adapt and grow from challenging experiences. With personal intention and support systems, leaders can help build resilience as a bridge across uncertainty that will not only sustain the workforce through crises and help them manage stress going forward, but also lead people to surprisingly positive outcomes as they emerge on the other side of a crisis.1

Learn more

Explore the Human Capital collection

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Organizations should play a vital role in relieving stress overload before, during, and after a crisis.2 After all, people typically spend more time at work than any other daily life activity, and the effects of stress can have a significant impact on work. Indeed, the toxic stress overload caused by a crisis can diminish individual and broader human capital.3 Beyond the visible impact of crises on personal health, family, and financial stability, sustained toxic stress can impact the part of the brain responsible for executive function. This negative impact can weaken working memory, attention control, cognitive flexibility, and problem-solving—the cognitive processes that make people capable and productive both in their personal and professional lives.4 Further, when a crisis is widespread, as with COVID-19 and other recent events, stress can diminish the broader well-being and productivity of a company’s workforce, leading to significant implications for the business as a whole.5

Organizations should play a vital role in relieving stress overload before, during, and after a crisis.

In this article, we will focus on how leaders can help their workforce and organization adapt after crises by helping develop resilience in individual workers. This can enable a level of stability during crises and allow for the company—bolstered by the strength of a resilient workforce—to move forward positively and thrive in the future in a potentially changed world and business environment.6

Whatever your business, with your workforce behind you, you can rally as an organization to create opportunities when the crisis has passed.7 Taking care of your people by helping them manage stress to build resilience protects the investment you have already made in them, which in turn can protect your investment in your business.8

Stress: How do people get from “good stress” to overload and back again?

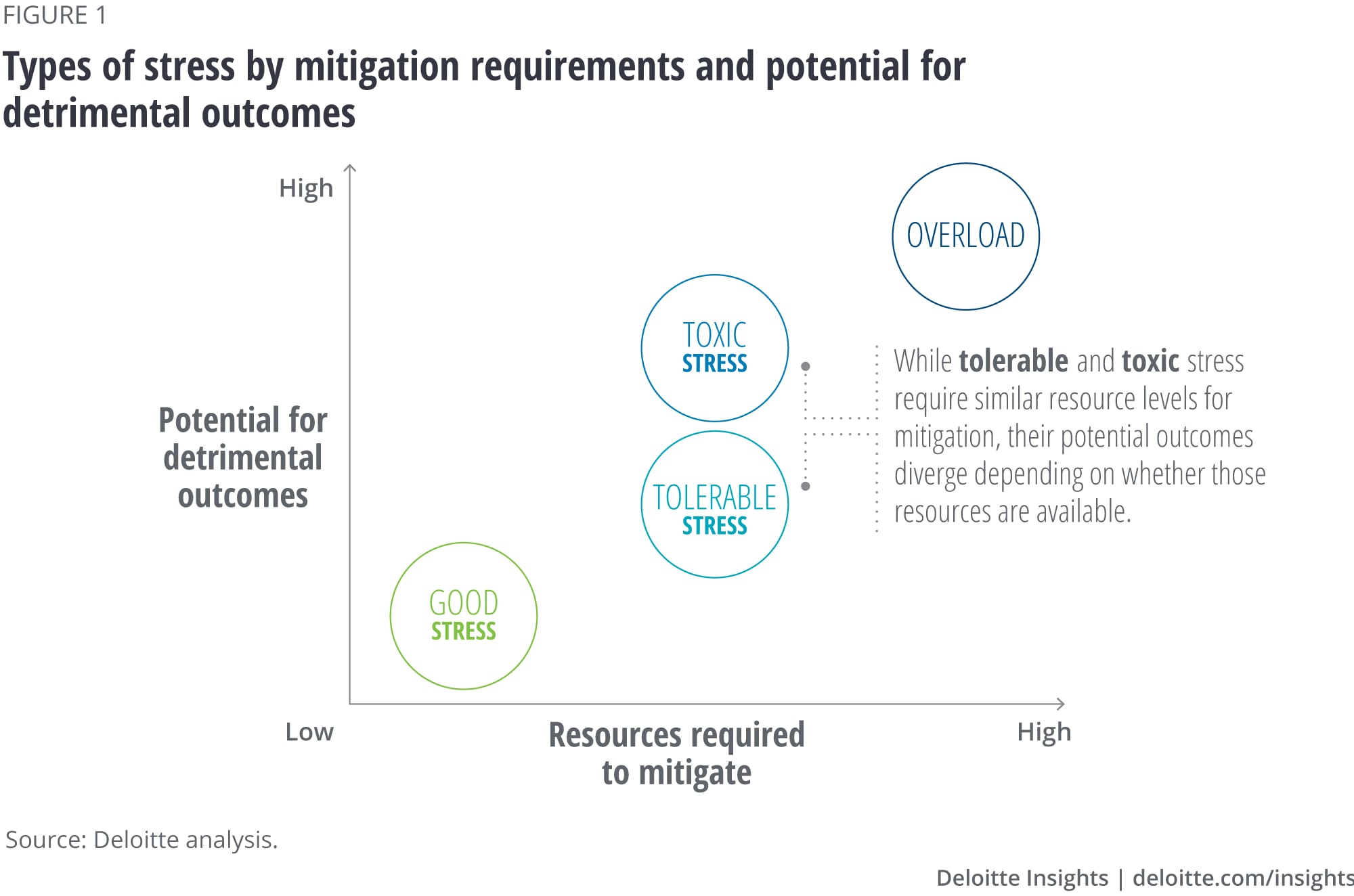

Stress is a ubiquitous word and experience. We may all intrinsically know what stress means to us, but that doesn’t mean we define, experience, or respond to it in the same way. In fact, there is more than one type of stress, and people’s responses to each can also vary.9 Research has demonstrated that, broadly speaking, people experience three types of stress: good stress, tolerable stress, and bad or toxic stress.10

- Good stress can be characterized by a stressful situation that results in a positive outcome; for example, the nerves felt before delivering an important presentation. In these cases, stress can result in growth.

- Tolerable stress occurs when something challenging or bad happens, but with internal and external resources, the circumstances can generally be weathered, and recovery is largely assured and can be seen on the other side. One example of tolerable stress may be the experience of an illness or surgery, from which people are able to recover and during which they have the help of their support systems.

- Bad or toxic stress occurs when something bad happens, but people don’t have enough resources or support to weather that stress. It can be caused by many types of events, both personal or more global, such as the loss of a job during an economic downturn followed by long-term unemployment. The resulting emotional and financial implications with insufficient support or mitigation can lead to negative mental and physical health outcomes.11

Unpredictable and uncontrollable events in the world around us can trigger a tremendous and relentless form of toxic stress, or overload, which has the power to overwhelm people’s day-to-day capacity to combat that stress.12 Overload is the rogue wave of toxic stress; it is immense, often strikes without warning, serves no useful purpose, and, without purposeful intervention, inclines those who experience it to potentially serious mental and physical health outcomes.13 When toxic stress builds up or people reach a state of overload in a crisis, active intervention may be warranted to mitigate stress alongside the development of resilience in both the short and long term. Mitigating toxic stress and building resilience allows for successful adaptation on the other side of stressful events.

Bouncing forward: Stress mitigation and resilience development

Resilience is often defined as the ability to “bounce back” after adversity, but when it comes to toxic stress in times of crisis, a more forward-looking definition may serve us better. In building resilience, then, leaders may find it more effective to aim for developing within their teams the ability to bounce forward and exist in stability on the other side of adversity, or in the period known as adaptation, and beyond.14

Resilience is an emotional muscle that must be strengthened to overcome short-term struggles and maintained to offset a lifetime of challenges. Even though building resilience may not always be the most pleasurable activity, it is something that can pay dividends when cultivated and maintained with intention. It can also be easier said than done: While many of us believe that we are highly mentally and emotionally resilient, data shows we may be overestimating our own resilience to stressful events.15

Understanding the impacts of unchecked stress and the necessity of building resilience

The consequences of unmitigated toxic stress on workers who have not built resilience can be a short, slippery slope, which becomes shorter still as the stressors increase in magnitude and duration. For example, a lack of sleep triggered by stress can lead to rising blood pressure, cortisol levels, inflammation, and insulin levels, which over time can lead to cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.16 Sleep deprivation can also lead to cognitive impairment by causing atrophy of certain brain regions which can impact memory, attention, and executive function, along with the areas that regulate fear, anxiety, and aggression. This can hamper workers’ abilities to learn, remember, and make decisions and increase their levels of anxiety and depression.17

The outcome of these negative impacts for organizations predominantly falls into two categories: productivity losses and direct financial impact.18 According to studies, distressed workers are significantly less productive than those who aren’t, spending a third of their scheduled work time hampered by “presenteeism,” or an at-work decline in productivity, and losing nearly an additional day each month to its better-known cousin, absenteeism.19 Customer service levels can also fall as stress rises.20 Direct financial impacts can include an increase in health insurance claims, short- and long-term disability, and costs related to increased employee turnover (See “Workforce experience and its impact on customer service” sidebar).21

Customer service levels can also fall as stress rises. Direct financial impacts can include an increase in health insurance claims, short- and long-term disability, and costs related to increased employee turnover.

Workforce experience and its impact on customer service

High-impact workforce experience organizations are 1.6 times more likely to achieve better customer outcomes.22

Companies in the top quartile of workforce experience are typically 25% more profitable than competitors in the bottom quartile.23

Companies that built a seamless and innovative workforce experience show twice the customer satisfaction reflected in their net promoter score.24

This correlation between individual stress and performance is notable, and the compounding effects of this when a crisis impacts the whole workforce have the potential to disrupt business operations. Such an outcome is not preordained, however, and moving from toxic stress to a more tolerable and productive form is tied to the development of resilience. The development of resilience is often not only a critical component of responding to or planning for disaster and related crisis situations; it is also typically an important part of an organization’s overall worker well-being strategy.25 Organizations and leaders, in particular, have much to offer their workers when it comes to managing stress and building resilience. One framework organizations can leverage focuses on three time frames for intervention to mitigate the impacts of toxic stress and allow workers to build resilience: readiness, response, and recovery.26

Readiness

In the readiness phase, organizations can proactively create a positive workforce experience and provide resources that allow workers to consistently manage their stress and build resilience. Leaders can play a key role in the workforce experience and have many options for doing so, including developing psychological safety at the workplace, providing a robust set of well-being benefits and programs, and even seeking to make a difference in the communities in which their workers live.

Psychological safety at work is the condition of candor,27 or trusting and feeling respected while being your authentic self as you work, learn, and team without fear of negative consequences.28 In the long term, workers commonly thrive in this environment, and this is seen through increased engagement and improvements in learning, performance, and collaboration.29 It becomes even more important during a crisis though, as the positive emotions associated with psychological safety (e.g., trust, confidence, relation) can help people become more resilient, motivated, and persistent.30

Worker well-being and psychological security need to extend beyond the walls of the workplace, and while well-being programs may seem like table stakes, they can’t be overlooked in any phase of worker stress mitigation. It’s important to note that for years leaders have recognized that they are consistent means of mitigating the negative impacts of stress on productivity and the bottom line.31 The availability and communication of these programs can also contribute to the development of workers’ internal locus of control with regard to their own well-being, empowering them to make positive decisions and take action when toxic stress becomes pervasive.32

In the readiness phase, organizations can also consider what are known as primordial preventions, or actions they can take via involvement with community stakeholders that help address the social factors that can lead to insecurity, including broader income, education, and housing programs. 33

Worker well-being and psychological security need to extend beyond the walls of the workplace, and while well-being programs may seem like table stakes, they can’t be overlooked in any phase of worker stress mitigation.

To recap, in the readiness phase, some key ways in which organizations can support resilience are the following:

- Intentionally and consistently develop a psychologically safe work environment

- Provide, communicate, and advocate the utilization of well-being benefits and programs

- Example: Some organizations have begun to shift from implementing well-being programs that are adjacent to work toward designing work for well-being; these organizations could be in a strong position to bolster and leverage worker resilience34

- Design benefit programs that are culturally relevant based on your population and solicit input from across your diverse workforce

- Consider actions within workers’ communities that can positively impact social issues and insecurities

- Example: A number of companies give paid time off for employees to volunteer in their communities or vote in elections, demonstrating a commitment to civic and community engagement35

Response

In the response phase, organizational and leadership action is triggered by crisis, but even at this stage, organizations can proactively approach stress removal and prevention. First, leaders should pursue insight into their unique workforce and their needs in order to effectively respond with them in mind. Having understood those needs, they can then facilitate worker resilience through strong, authentic business leadership and by securing business continuity to the extent possible.

While leaders normally aim to ensure business results in support of all company stakeholders, it can be critical that during a crisis, leaders remember that their workers are among the stakeholders who rely on the organization’s resilience for job security and financial stability. Beyond focusing on business continuity, leaders can prioritize regular communication with workers, using a human-centered approach that focuses on empathy, authenticity, and transparency.36 Communications during a crisis may not always be a rallying cry—or even positive news overall—but demonstrating a connection and commitment to your workforce by showing that you prioritize their well-being is important to developing their trust. Trust requires that through words and deeds a leader is transparent, fosters a relationship with employees, and demonstrates an ability to address challenging situations in a way that considers the needs of those employees as meaningful stakeholders. That trust can be critical to recovery both for workers and for the organization.37

During this phase, organizations can turn their attention beyond the individual to the workplace and broader well-being efforts. In the arena of work and workplace, organizations can ensure that workers are equipped for and supported in new work environments—and are safe and supported in traditional workplaces which may have become more hazardous.38 In terms of broader well-being, organizations which are already providing well-being programs that focus on the financial, physical, mental, and social well-being needs of their workforce can evaluate them critically with an eye for any gaps that may emerge in interventions which may need to be supplemented in light of the current crisis.39 Organizations can also promote these programs, reiterating what is available, highlighting new resources, and encouraging workers to take advantage of benefits and programs by ensuring there is no stigma around doing so.40

According to the Deloitte 2020 Human Capital Trends Survey, prior to the COVID-19 crisis, only 26% of respondents reported that their leaders consistently practiced and promoted well-being.41 This suggests that there likely remains an opportunity for leaders to not only promote but also demonstrate a particular commitment to well-being in the midst of present turbulence and in the adaptation period that follows.

To recap, in the response phase, some key ways in which organizations can support resilience are the following:

- Understand your unique workforce—their needs and challenges—in static times and times of crisis

- Include your workforce as a key stakeholder in securing business continuity while remaining agile to respond to both business and workforce needs

- Example: During the COVID-19 crisis, businesses that could shift quickly to a remote work model were able to facilitate business and workforce continuity more seamlessly42

- Communicate transparently and authentically to build trust

- Evaluate, augment, and destigmatize the use of well-being benefits and programs

- Example: Many companies are augmenting well-being benefits across the spectrum to ensure worker health and stability, including dependent care stipends, expanded access to telehealth resources, and even company-sponsored access to meditation resources.43

Recovery

In the recovery phase, workers are testing their resilience as they adapt to a changed environment. While some may be fully prepared to take on new challenges, some may need additional time or assistance in mitigating lingering toxic stress or treating negative psychological or physical conditions that may have manifested during the crisis.44 Should the psychological or physical symptoms associated with the build-up of toxic stress require treatment, it is also important in the recovery phase that workers are reassured that resources will continue to be available to them and that they feel psychologically safe enough to use them.

To recap, in the recovery phase, some key ways in which organizations can support resilience are the following:

- Maintain reasonable and flexible expectations for workforce adaptation when the crisis begins to resolve, and support workers who may need additional time and interventions for stress mitigation

- Example: While many companies have offered a range of well-being support services after crises, the ones that have been particularly successful have facilitated or encouraged peer-driven employee support groups45

By making a commitment to the above actions as an investment in enduring human and psychological capital, organizations can build a powerful foundation of mutual trust in their work community. This trust can enable workers to respond better to the crisis at work and at large as individuals and an organization as a whole.46 The actions taken during these phases, then, as they provide stability, space, and opportunity for building resilience, can unlock the path to positive and fruitful recovery and adaptation for both workers and their organizations.

Be a leader at building resilience within the work environment

Helping your workers build resilience generally requires honest engagement and trust, and certain qualities of leadership have been shown to correlate with employee engagement.47 Motivating and inspiring workers, alongside having a positive and openly communicative leader-worker relationship can build the engagement and trust that will give you a foundation to guide your workers in building their resilience.48 Having commited to building engagement and trust, leaders can foster resilience by creating a work environment, be that physical or virtual, that supports workers:

Foster a sense of belonging among workers and within the organization:49

- Belonging can be a twofold solution in the workplace.

- Positive, interactive relationships and the social support that they create for workers are often a natural buffer for stress and can prevent tolerable stress from becoming toxic.50 They can also physiologically improve worker health and function by augmenting critical brain function.51

- Another important aspect of belonging is creating meaning through work. When workers can see how their contributions create a positive impact for the organization, their work may feel more meaningful and their comfort and connection to the organization often increases along with their ability and desire to contribute further.52

Enable an internal locus of control:

- While there are many circumstances that are out of workers’ control, those who perceive and process events and outcomes as within their control are likely to have enhanced emotional resilience.53

- Support autonomy and flexibility. By doing so, you can encourage creative problem-solving that could serve workers when they face larger challenging situations.54 Allowing workers the autonomy and flexibility to manage their work and balance their other concerns can allow for a more internal locus of control, potentially diminishing some anxiety and enhancing emotional resilience and overall stability.55

- Creating opportunities for growth and development is another way to help workers embrace change consistently. The consistent challenge of growth and development can better equip them to face difficult changes that may arise.56

Be resilient, transparent, empathetic, and authentic:

- Be a resilient leader by consistently leading from the heart and the head—not only by ensuring that your business is stable but also by being actively and authentically empathetic toward your workers, among other stakeholders.57

- An important aspect of being a resilient leader is communicating openly and regularly, sharing the information you have, and fostering dialogue in a psychologically safe environment. The way your communication is delivered and perceived by your workers is also fundamental for building long-term trust, which can help during a crisis.58

- Finally, start having conversations about resilience before it becomes critical. Coach workers on resilience, encourage managers to hold guided conversations with their teams, and promote regular conversations among team members to ensure that everyone is able to discuss adversity and how they do or can overcome it. Having these discussions regularly can prepare workers for when the challenges and conversations get tougher.59

For additional reading on resilient leadership, we recommend these recently published pieces:

The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to COVID-19

Embedding trust into COVID-19 recovery

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19

The perseverance of resilient leadership: Sustaining impact on the road to Thrive

Adaptation: Where the rubber meets the road

In the adaptation phase, workers emerge on the other side of crisis; their state of being, lives, or the world they live in have been altered, and may be altering still. It is the other side of the bridge across uncertainty, but what awaits people is not entirely certain, defined, or fixed either; it is where crisis-tempered resilience is tested.60 However, despite the brain’s vulnerability to overload, research shows it also has the capacity to adapt in positive ways with support and encouragement. Moreover, out of crisis comes growth: Periods of transition and great change can make the brain even more adaptable and poised for positive change despite challenging circumstances.61

In this state, people can find a greater sense of appreciation for life and relationships and new wells of internal strength, confidence, purpose, and meaning.62 This effect is not limited to individuals, and in fact, can also be seen in communities. It manifests itself in the deepening of a shared sense of purpose, interconnectedness, and cooperation.63 An organization that from at least the outset of a crisis has recognized and embraced its collective power and its responsibility to individual workers and the broader workforce as important stakeholders has the ability to benefit from the same effects.64 The powerful combination of individual and community resilience can increase a workforce’s capacity and desire to help the organization recover and thrive.

While the idea that human brains remain adaptable throughout our lifetime is a recently acknowledged truth,65 this, along with the knowledge that it is also more plastic during periods of transition should fortify leaders in their resolve to foster resilience among their workforce—their community. If leaders can support and inspire their workforce to build resilience, they could be better prepared to take on the challenges that come with rebuilding or evolving a business model and thriving in the aftermath. Having ushered their businesses and their people to the other side of that bridge, leaders will be faced with a new start line from which they should be prepared to launch. From this new start line, they can forge ahead with their workforce as a community: resilient, adaptable, and ready to take on the future of work as it awaits on the other side of the bridge across uncertainty.66

In the aftermath of recent crises and the rapid acceleration of change these crises have engendered, we may find that uncertainty is one of the only certainties, and with that in mind, it is important that leaders recognize that helping the workforce build resilience is not just a for-now activity, but rather one that should remain part of the organization’s readiness strategy to serve the workforce and the business going forward.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Human Capital collection

-

2025 Global Human Capital Trends Article3 weeks ago

-

Confronting the COVID-19 crisis Podcast5 years ago

-

Superlearning Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the undisruptable CEO Article4 years ago

-

Mitigating bias in performance management Article4 years ago

-

Staying grounded in uncertain times Podcast4 years ago