Why 2020 could be a dangerous year for the US economy Economics Spotlight, October 2018

25 October 2018

A confluence of factors—withdrawal of fiscal stimulus, Fed rate hikes, and tariffs and trade restrictions—will likely render the US economy weak by 2020. But these may not be enough to support forecasts of a looming recession.

It’s no secret that economists aren’t very good at predicting recessions.1 Times must be unusual when forecasters are willing to guess that the most likely time for a recession is just over a year away.

Deloitte’s Q2 US Economic Forecast reflects this view.2 The forecast projects a highly unusual pattern for GDP. Instead of a gradual movement toward the long-term growth rate, which Deloitte estimates at 1.6–1.7 percent, the forecast is very positive for 2018 (at 3.0 percent), positive for 2019 (2.4 percent), and then suddenly dips to just 0.7 percent in 2020. And, the recession scenario in the forecast assumes that the next recession will start at the very end of 2019.3

Deloitte economists are not the only ones to signal concerns about the economy in 2020. Half the panel of economists in a survey of business economists expects the next recession will occur between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020.4

The reason economists suspect that the end of 2019 and 2020 will be times of economic weakness is because of the current economic policy. Policy decisions about taxes, spending, interest rates, and tariffs taken over the past year have made late 2019 and early 2020 the possible time for a perfect storm to hit the economy. Fiscal, monetary, and trade policy may combine at that point to drag down economic growth. A recession is not guaranteed, but in the environment of a perfect policy storm, the economy will likely be more vulnerable to shocks, for example, spikes in commodity prices or financial crises.

Withdrawal of fiscal stimulus means government spending will weigh down the economy

The first element of the storm is the end of the fiscal stimulus put in place in late 2017 and early 2018. That stimulus had two elements (figure 1).

First, there was a large tax cut. In April, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that legislative changes since June 2017 let taxpayers keep an additional US$163 billion in 2018 and US$285 billion in 2019.5 That’s a stimulus of over 0.8 percent of GDP in 2018 and 1.3 percent of GDP in 2019. But after 2019, the tax cut stimulus stops growing—and even declines slightly in FY 2020.

Second, in January 2018, Congress eased its budget problems by passing a two-year spending agreement that included a substantial increase in spending. The additional spending brought enough members of Congress on board to allow the budget to pass. But there was a cost. The CBO estimates that legislative changes between June 2017 and April 2018—mainly the Budget Act of 2018—will increase the deficit by US$108 billion (about 0.5 percent of GDP) in 2018 and US$174 billion (0.8 percent of GDP) in 2019 (compared to the level estimated before the act passed).6 After that, however, CBO estimates show the stimulus falling. Thus, government spending is set to add substantially to growth until sometime toward the end of FY 2019. At that point, government spending is likely to start to be a drag on the economy. At the same time, the tax cut will be fully phased in by 2020, and, according to CBO calculations, no longer providing additional stimulus.7

Fed rate hikes will start to hit

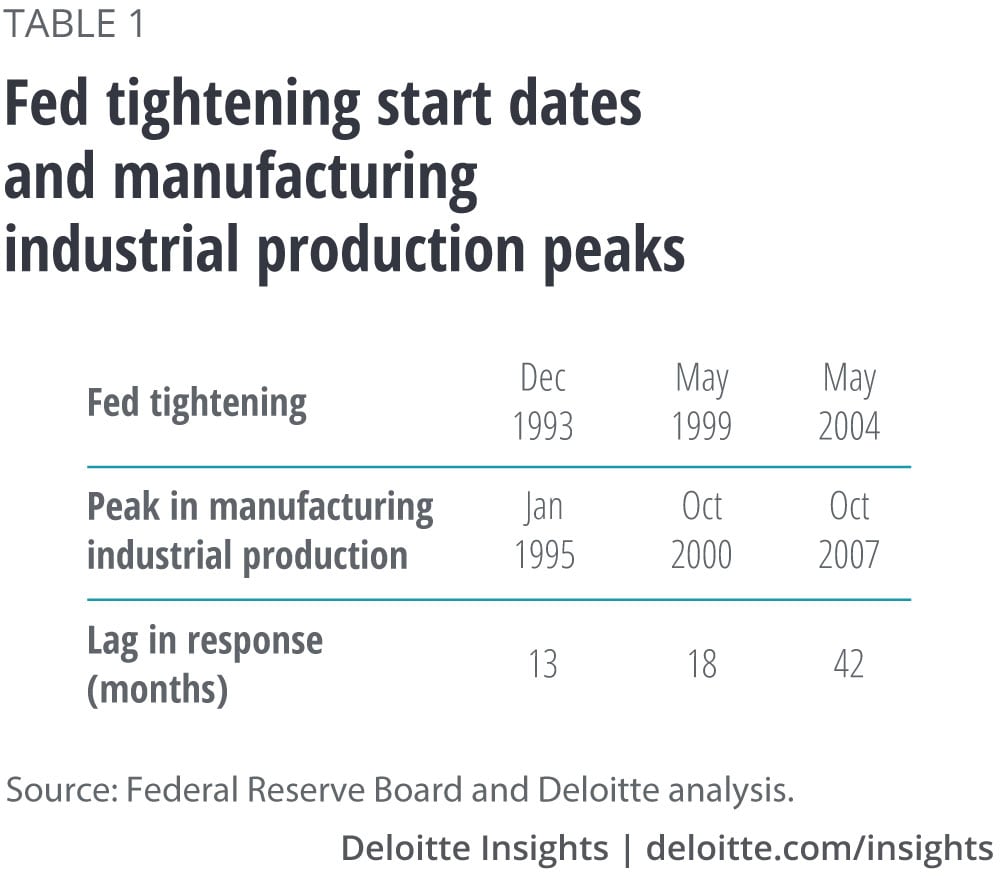

The Fed raises interest rates to slow the economy and prevent inflationary pressures from building. But it’s not easy, because interest rates only affect economic activity “after a lag that is both long and variable.”8 Table 1 compares the dates of the starts of the three most recent tightening cycles by the Fed with the date at which industrial production peaked. The usual impact seems to be within a year to a year and a half, which would be consistent with many economists’ beliefs. But the economy continued to grow for quite a long time after the 2004 hike. As Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan noted at the time,9 the Fed’s hikes in short-term rates did not translate into rising longer-term rates as historical experience expected. That was certainly part of the reason that Fed policy did not constrain economic activity during 2005–07.

The Fed’s current tightening cycle started in December 2015, although it took a year before the Federal Open Market Committee raised rates again. Between December 2015 and September 2018, the Fed raised the midpoint of the target rate about 200 basis points. Yet the yield on the 10-year note is up only about 40 basis points. Long-term rates are being held down by increasing risks overseas, which is driving investors to purchase safer US assets (and drive up the value of the dollar). But that could change, and the Fed is likely to continue to raise rates in 2019. In fact, the stimulus will likely increase inflationary pressures in the short term, and that might lead the Fed to raise rates more than the underlying strength of the economy requires. It is very likely, therefore, that interest rate hikes will begin to affect economic activity some time in 2019, adding to economic weakness in the latter part of the year.

Tariffs are a wild card

The third area of policy that promises to weaken growth is in international trade. Over the course of 2018, the United States has raised taxes on some imports. By late September, the United States had hiked tariffs on 12 percent of US imports, while retaliation from US trading partners covered about 8 percent of exports.10 The administration had mentioned or discussed tariffs on a larger variety of goods, including autos, which would represent a more substantial increase in overall prices for imports.

The static analysis of the impact of imports suggests that this will have modest effect on the economy. Model-based simulations suggest declines in GDP of up to half a percent per year for several years, although much depends on the assumptions behind the simulation.11 Not only do the modelers differ in their assumptions about US policy, they also differ in their assumptions about how strongly foreign governments will respond.

Nevertheless, there is some room for pessimism. First, much of the modeling doesn’t fully take into account the existence of global supply chains and the difficulty of replacing more expensive imports at short notice. Second, the impact will be relatively large if US trading partners respond harshly.

The US economy has only begun to adjust to the new global price structure resulting from the tariffs placed on foreign goods, and the final result remains very uncertain. There is no guarantee that US trade policymakers will not continue to ratchet up tariffs, or that US trade partners will not continue to respond by raising tax rates on US imports. This suggests that late 2019 and early 2020 could well be the time when the impact becomes evident. Not only will companies be reaching the stage where hastily acquired pre-tariff inventories could have run out, but they are likely to react to the uncertainty about tariffs by delaying expansion or holding off on new investment until the long-run implications of the new trade regime become clear. This softening of investment may be felt by early 2020.

Recession is not inevitable

By themselves, these three policy impacts are not likely to be large enough to create a recession. Deloitte’s baseline forecast shows a substantial slowing of GDP growth—but it remains positive, with a modest increase in the unemployment rate. For an economy that is operating or near full employment, the impact might even be welcome if the 2018–19 fiscal stimulus proves to spark some inflationary pressures.

However, these policy impacts will likely create an extraordinarily weak economy for several quarters. Even a small shock to the financial system, or an unexpected increase in commodity prices, might be enough to push the economy into a recession.

This is no secret. It’s precisely why the business economists cited earlier are willing to take the risk of looking farther ahead than usual for the date of the next recession. And it’s why Deloitte’s US forecasting team raised the risk of recession to 25 percent, and placed the next recession in the late 2019 to early 2020 time frame.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.