Trade disputes will weigh on the economy, but by how much? Economics Spotlight, August 2018

25 August 2018

Many economists’ estimates of the impact of tariffs on the US economy are quite modest currently. However, should an all-out trade war develop with Asia and Europe, the interruption of global supply chains could result in a much bigger drag on the economy than currently estimated.

Cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of trade war!1

The past few months have seen a growing number of tit-for-tat trade actions among many of the world’s important trading partners, including the United States, China, and Europe. Suddenly the term “trade war” appears to be attracting a lot of attention, as shown by a sudden spike in Google searches for the term.2

Is it officially a war? It’s not a well-defined term, and many national leaders may wish to use language to soften (or harden) their positions. Whatever it’s called, since spring, the United States has been involved in a set of trade policy actions—most notably tariffs justified officially by national security concerns3—which have elicited retaliation from US trade partners.

Most economists aren’t impressed by these policy actions. If there is one thing that almost unites the economics profession, it’s that free international trade raises efficiency and overall incomes.4 Even some of the president’s economic advisors agree—the chair of the Council of Economic Advisors recently stated, “We need to move toward a world where trade barriers around the world come down, not just for us, but for our trading partners.”5

So most economists subscribe to the idea that a trade war is a bad idea. That means they likely expect it to reduce GDP. But how much GDP is at risk, and exactly how bad an idea is this?

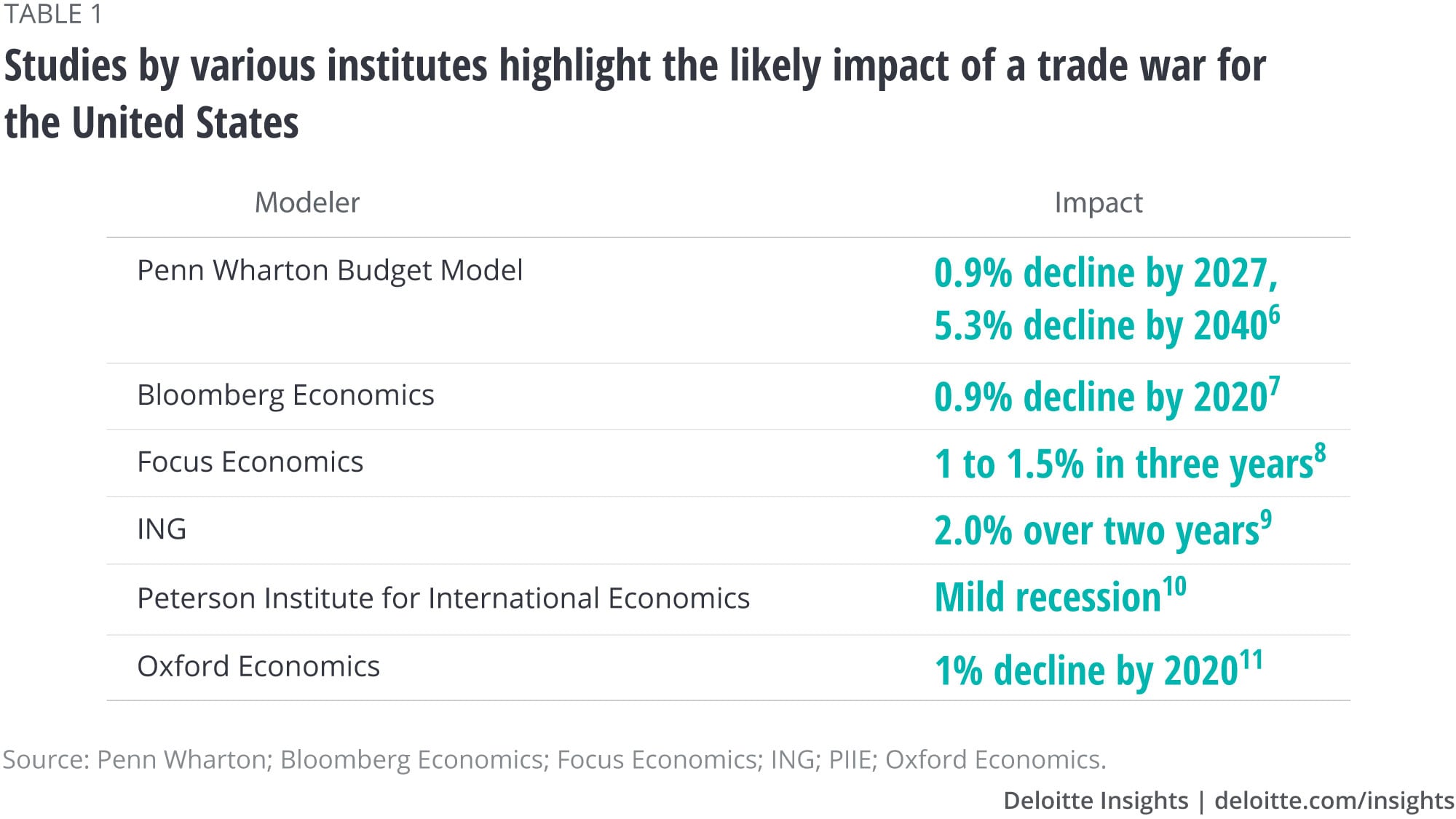

A survey of some recent studies suggests that US GDP under some type of trade-restrictive regime might be 1–2 percent lower in 2020 than it would have been without the trade war (table 1). The studies vary in their assumptions about how a trade war might occur, and how strongly other countries would react to US tariffs. But except for the Peterson Institute’s simulation, the consensus is that a trade war would not cause a recession (and even the Peterson Institute expects a very mild recession).

Models used to analyze the impact of trade restrictions typically assume that it is possible to calculate the impact by multiplying the size of the tariff by the amount of imports to obtain a price impact. When fed into a macro model, this will result in a decline in GDP. These impacts are quite modest for the United States. For example, a 25 percent tariff on all Chinese imports would result in an overall price rise of just 0.6 percentage points (based on the fact that Chinese imports were 2.6 percent of GDP in 2017).12 Such a one-time increase would likely be too small to trigger sustained inflation or other macroeconomic problems.

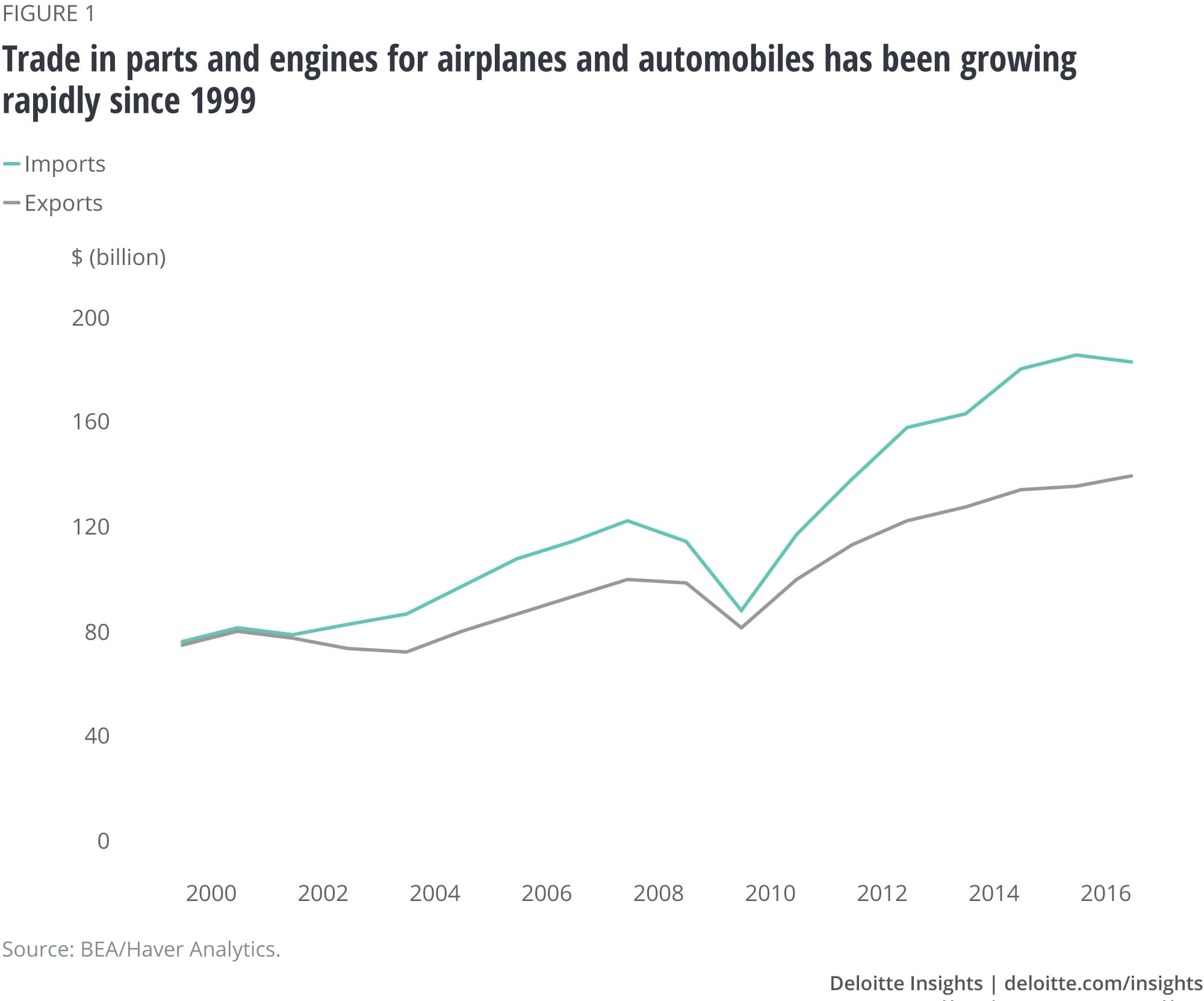

But there is some reason for caution, because these calculations do not take into account the impact of a sudden jump in the price of key inputs on today’s complex, global supply chains. Many US manufacturers use more foreign parts to produce final products, and sell more parts to foreign manufacturers, than in the past. Figure 1 shows trade in one set of such intermediate products—parts and engines in the transportation sector—has been growing quickly. For both aircraft and motor vehicles, the value of such exports is about twice what it was in 1999, and the value of imports almost three times as much. This is the direct consequence of the increasing cross-border supply chains (for example, in the three NAFTA countries of the United States, Mexico, and Canada).

To better understand why this impact matters, consider the 1973 oil shock—when the price of imported oil rose almost three-fold. This was essentially similar to a tariff, or tax increase on imported oil (with the key difference that foreign oil producers, not the US government, reaped the benefits of the price increase). When weighted by the importance of imported oil in the US economy (oil imports were about half a percent of GDP), this should have had a one-time impact of 1.5 percent on the US price level—more than our Chinese example, but certainly a relatively modest impact.

However, the oil price rise contributed to creating a deep recession. Oil, it seemed, was special. As energy is an essential commodity for all industries, price rises were felt everywhere. Nor were there easily available replacements for oil, especially in the short run. As a result, the sudden oil price hike led to an unemployment rate that briefly hit 9 percent in 1974.

The new US tariffs are more modest, but the wide share of goods imported from China (and other targets of US tariffs), combined with the globalization of supply chains, may create similar problems for US companies. In some cases, there may be no easily available substitutes for the imports. In other cases, the rise in import prices will likely affect the supply chain in complex ways. For example, producers of final goods will want to make up the additional costs of intermediate inputs with higher prices, and also demand lower prices from domestic suppliers to compensate. Domestic suppliers of intermediates whose goods and services are together used with the imports will see a decline in demand.

Some of the capital stock of the United States—designed to be profitable under free trade—may no longer be profitable (technically, the US capital stock could suffer some depreciation as a result of the tariffs). US companies may therefore find it necessary to curtail operations and could lay off workers; also, overall economic activity could slow down by quite a bit more than would be suggested by the arithmetic above, indicating that costs of Chinese imports are a relatively small share of overall US costs. Some specific companies have already indicated that tariffs will force a curtailment of investment or even a full shutdown.13 Economists will be watching closely to see if the number of companies making similar decisions becomes large enough to move the needle on US aggregate manufacturing data.

The 1973 example suggests a further problem. At the time, the Fed—presented with a rise in inflation at the same time as rising unemployment and a stalling economy—had trouble reacting in a coherent manner.14 This was partially because Fed economists at the time did not have good models of how the economy could operate with accelerating inflation and rising unemployment at the same time.15 But it was also because there was a real dilemma when the monetary authority faced a “supply shock” of this sort. Rising prices called for higher interest rates to reduce demand, but rising unemployment called for lower interest rates. There was no way the Fed could have managed to achieve its dual objective of full employment and stable prices under these circumstances.

The Fed faces the same dilemma in the event of a trade war. Particularly in a full employment economy, a one-time rise in prices from higher tariffs could be felt as higher inflation. At the same time, the tariffs could lead to a slowing of employment growth—or worse, a significant rise in unemployment. The Fed may be forced to choose between rising inflation and high unemployment, an unenviable choice indeed.

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Marc Antony is fully aware of what will happen when he “lets slip the dogs of war.” In contrast, so far, financial markets as well as economists have assumed that the impact of a trade war on the US economy would be modest and contained. And while that might indeed be the case, the risks of a significant hit to GDP may be larger than many observers realize.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.