United States Economic Forecast 3rd Quarter 2018

14 September 2018

New tariffs have economists revisiting their old textbooks—and are leaving companies uncertain whether to begin rebuilding their supply chains. Our forecast sees a higher possibility of recession—though it’s still unlikely.

Introduction: Trade concerns

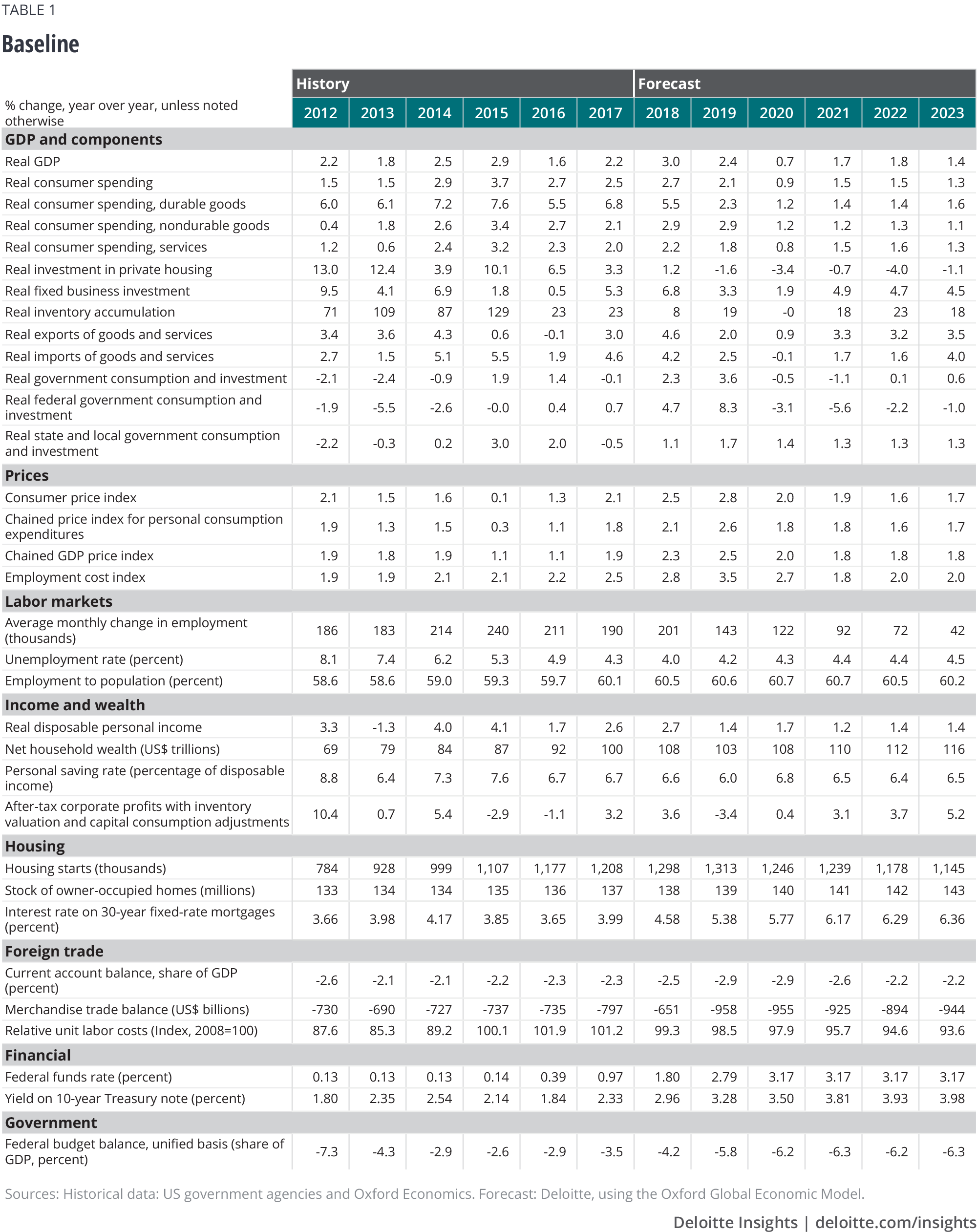

This quarter’s Deloitte forecast reflects two major changes, and they are related. First, we are reducing our 2019 growth projection to reflect both the likely impact of the US tariffs imposed so far this year and the impact of US trade partners’ retaliatory measures. Second, we are raising the probability of the recession scenario from 15 percent to 25 percent. The vulnerability of the economy to shocks such as a financial crisis increases with uncertainty created by the trade policy actions of both the United States and its trading partners.

Learn More

Explore our Economics collection

Subscribe to receive updates on Economic Outlook newsletter

The magnitude of the impact of the administration’s tariffs depends on whether they turn out to be temporary or permanent. Temporary trade restrictions might slow growth a bit for a year or two; permanent restrictions could have a substantial effect on the economy. In the long run, permanent tariffs would reduce aggregate output: The economy would simply be less efficient and companies overall less profitable. After all, it was efficiency and the resulting profits that led companies to build global supply chains and increase trade with agents in other countries.

Almost as important, the adjustment is likely to be difficult. In the short run, there may well be shortages and production bottlenecks as producers struggle to acquire supplies at a profitable price. In this way, the tariffs would function a bit like a supply shock such as an oil price increase. So it’s possible that the short-run impact might be even more painful than the long-run impact—and that the short-run pain may be felt even by people with skill sets and capital that tariffs should actually benefit.

International trade has become a significant source of uncertainty. Our scenarios provide a way to think through the different possible outcomes.

The revised Deloitte baseline forecast assumes that tariffs will reduce GDP growth by about 0.4 percentage points in 2019, offsetting some of the stimulus from 2017’s tax cut and budget agreement. The baseline also assumes that lawmakers remove tariffs by 2020, when the economy weakens as the impact of the 2018 budget agreement reverses. Even then, the economy grows just 0.7 percent in 2020, making it vulnerable to negative shocks.

The recession scenario assumes that tariff levels continue to rise, further reducing growth in 2020 and increasing the economy’s vulnerability to a shock.

The slow scenario assumes that tariffs remain in place, and that continued uncertainty surrounding trade policy suppresses investment spending.

The economic analysis of tariffs

The analysis of tariffs is a classic bit of economic theory going back to the 19th century. In recent years, tariffs have not been countries’ favored method of restricting international trade.1 But they are back. Of course, the basic theory of tariffs is as much a foundation of economics as Shakespeare is a foundation of the theater. And just as Cole Porter’s musical Kiss Me Kate advises to “brush up your Shakespeare,” economists are returning to their textbooks to revisit international trade theory.

In short, economists don’t like tariffs. Textbooks typically tell us that:

- A country that imposes an import tariff will see a decline in its own aggregate economic welfare.

- That tariff’s impact is uneven. Labor and capital used in producing import-competing goods will experience a rise in their rate of return, but that rise will be smaller than the decline in the rate of return experienced by labor and capital-producing export goods. (This is the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, for those trying to get an A in class.)

Economists often focus on the first proposition, but the second—the uneven impact—is a key fact of political economy. Over decades, the United States led a global movement to knock down trade barriers. Lowering barriers was good for the national economy in aggregate—and over the past 10 years, American attitudes toward trade have improved as the unemployment rate has fallen.2 But import-completing sectors did indeed see rates of return to capital and labor fall. That sounds bloodless, but it means that some companies failed and some workers found themselves trapped in locations and occupations that were not internationally competitive.

There’s another aspect of traditional trade theory to remember. It’s an equilibrium theory, meaning that it tells us what happens in the long run, once workers and businesses learn to live with the new trade regime. But getting to the long run (economists call it adjustment) might just be the most important problem the economy faces. The theory doesn’t say much about how adjustment occurs, but it involves getting capital and labor to move from one sector to another. It’s rarely easy. Some capital is trapped: Machines and buildings designed for one trade regime may be unprofitable under another trade policy. And workers may be trapped, too, since skills and locations that provide good wages under one trade regime may not be so useful under another trade regime. Those business and workers hurt by the changes in trade regimes may not be silent, even if the long-run overall outcome is positive.

Bottom line: Tariffs by themselves are unlikely to be large enough to create a recession. But growth is likely to slow a bit as costs rise, shortages appear, and businesses perhaps slow investment because of uncertainty about trade policy. All of this makes the economy more vulnerable to other shocks. So the Deloitte economics team has raised the probability of the recession scenario to 25 percent. That’s still quite a bit less likely than the baseline, but it indicates that risks are rising, and businesses should be prepared.

Scenarios

Our scenarios are designed to demonstrate the different paths down which the administration’s policies and congressional action might take the American economy. Foreign risks have not dissipated, and we’ve incorporated them into the scenarios. But for now, we view the greatest uncertainty in the US economy to be that generated within the nation’s borders.

The baseline (55 percent probability): Consumer spending continues to grow. A pickup in foreign growth helps to tamp down the dollar and increase demand for US exports, adding to demand. Fiscal stimulus from the tax bill and the budget agreement pushes growth up in 2018 and ’19 but is somewhat offset by the impact of US tariffs and foreign response. However, the US government comes to an arrangement with US trading partners, and the tariffs are removed fairly quickly. With the economy near full employment, the faster GDP growth creates inflationary pressures. The Fed responds with an aggressive interest-rate policy, and long-term rates rise quickly as alternative assets (abroad) become more appealing. A small increase in trade restrictions adds to business costs in the medium term, but this is offset by lower regulatory costs. As the impact of stimulus fades and the economy feels the effect of higher interest rates, growth slows below potential in 2020 and ’21.

Recession (25 percent): The economy weakens in late 2019 and early 2020 from the impact of tariffs and the withdrawal of stimulus as the additional spending from this year’s budget agreement goes away. With the economy already weak, a relatively small financial crisis pushes the economy into recession. The Fed and the European Central Bank act to ease conditions, and the financial system recovers relatively rapidly. GDP falls in the second half of 2020 and first quarter of 2019, and then recovers.

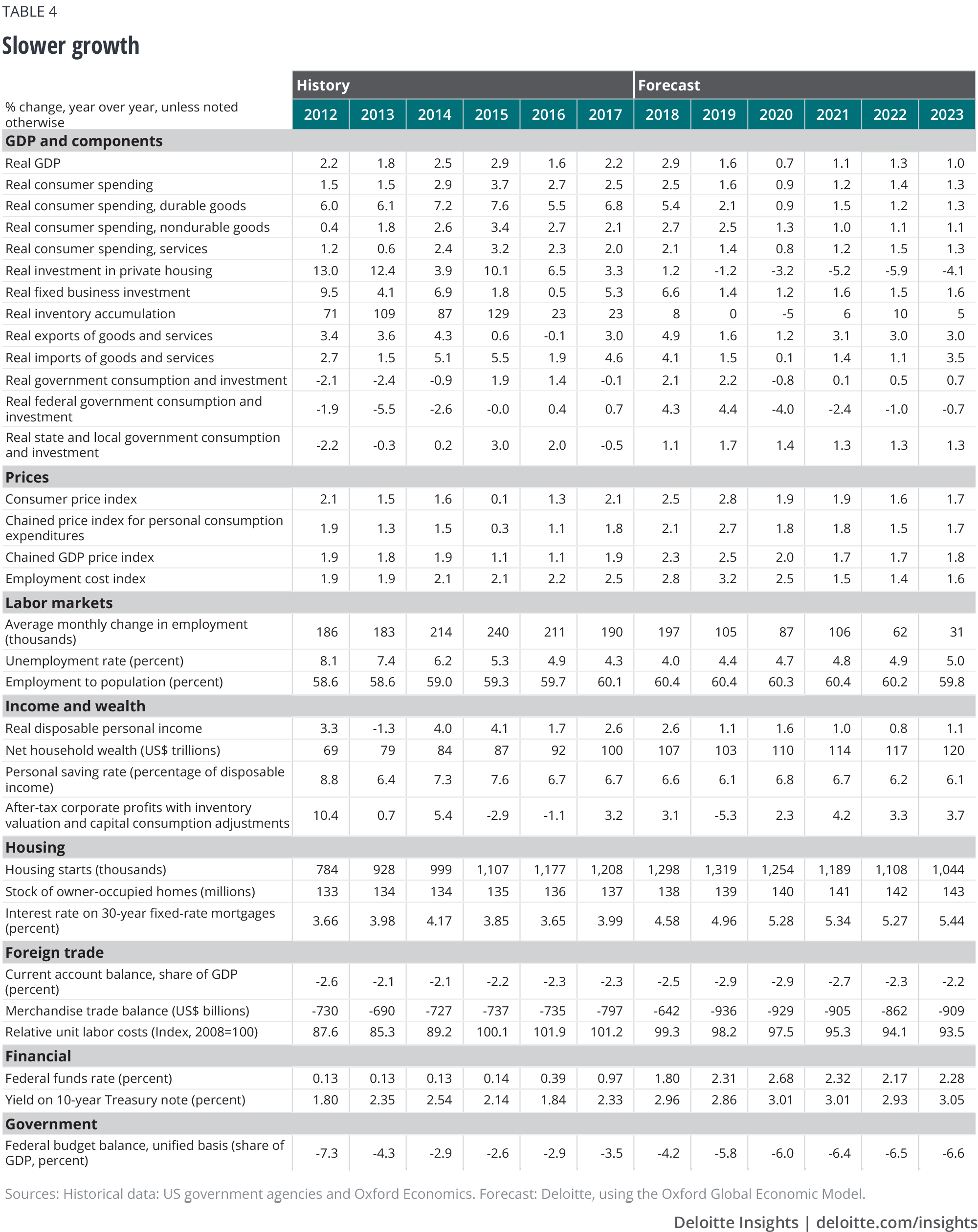

Slower growth (10 percent): Business tax cuts induce little investment spending, while households save their tax cuts. Tariffs remain in place as the United States and its trading partners can’t agree on new global trade arrangements. The tariffs raise costs and disrupt supply chains. Businesses hold back on investments to restructure their supply chains because of uncertainty about future policy. The higher spending authorization from the budget bill translates only slowly into additional federal outlays, reducing the budget bill’s impact on the economy. GDP growth falls to less than 1.5 percent over the forecast period, while the unemployment rate rises.

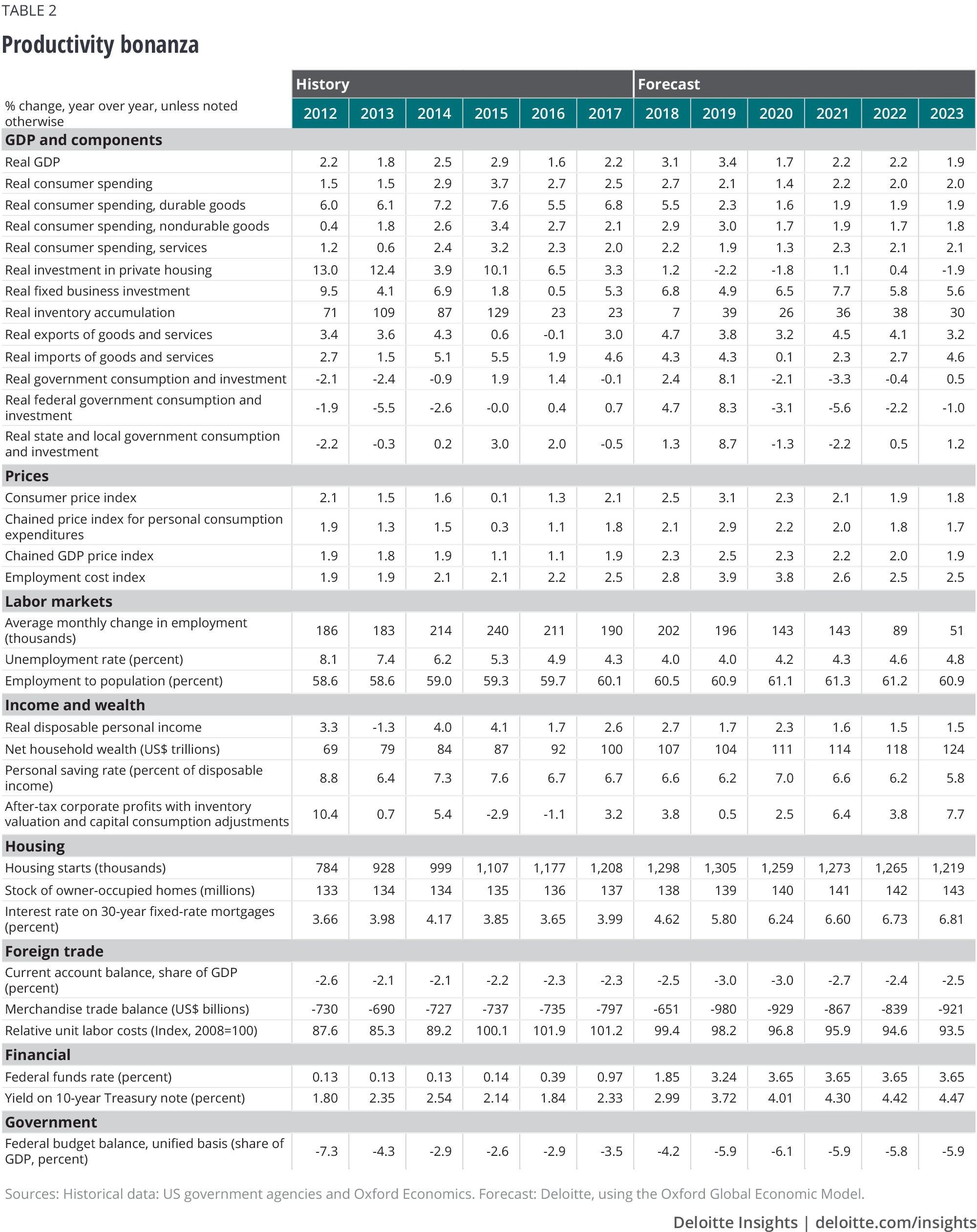

Productivity bonanza (10 percent): Technological advances in manufacturing begin to lower corporate costs, as deregulation improves business confidence. Improved infrastructure boosts demand in the short run and, in the long run, capacity and the productivity of private capital. Tariffs are short-lived and turn out to have a smaller impact than many economists expected. The economy grows over 3.0 percent in 2019, with growth staying above 2.0 percent between 2021 and ’23, while inflation remains subdued.

Sectors

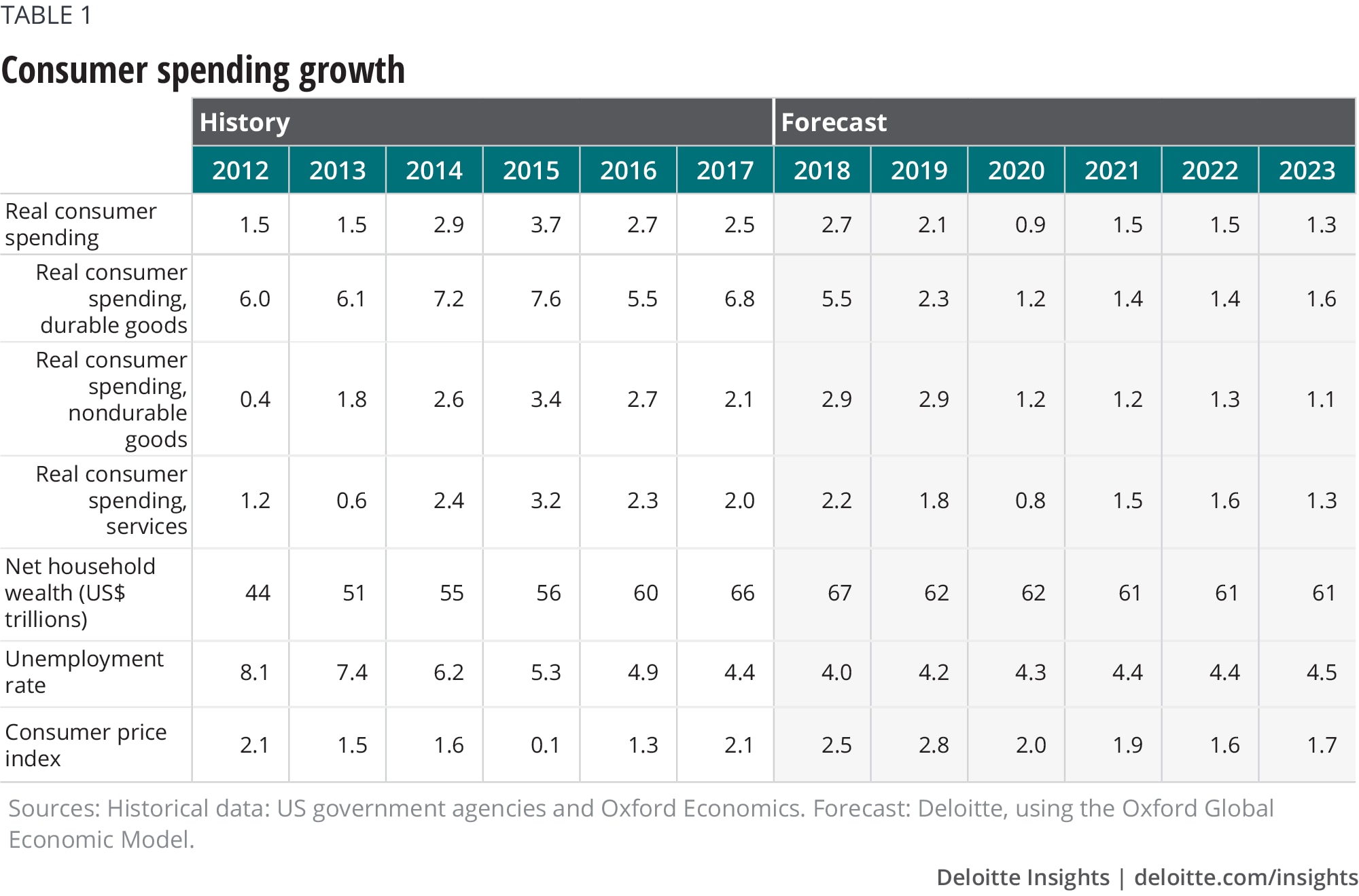

Consumer spending

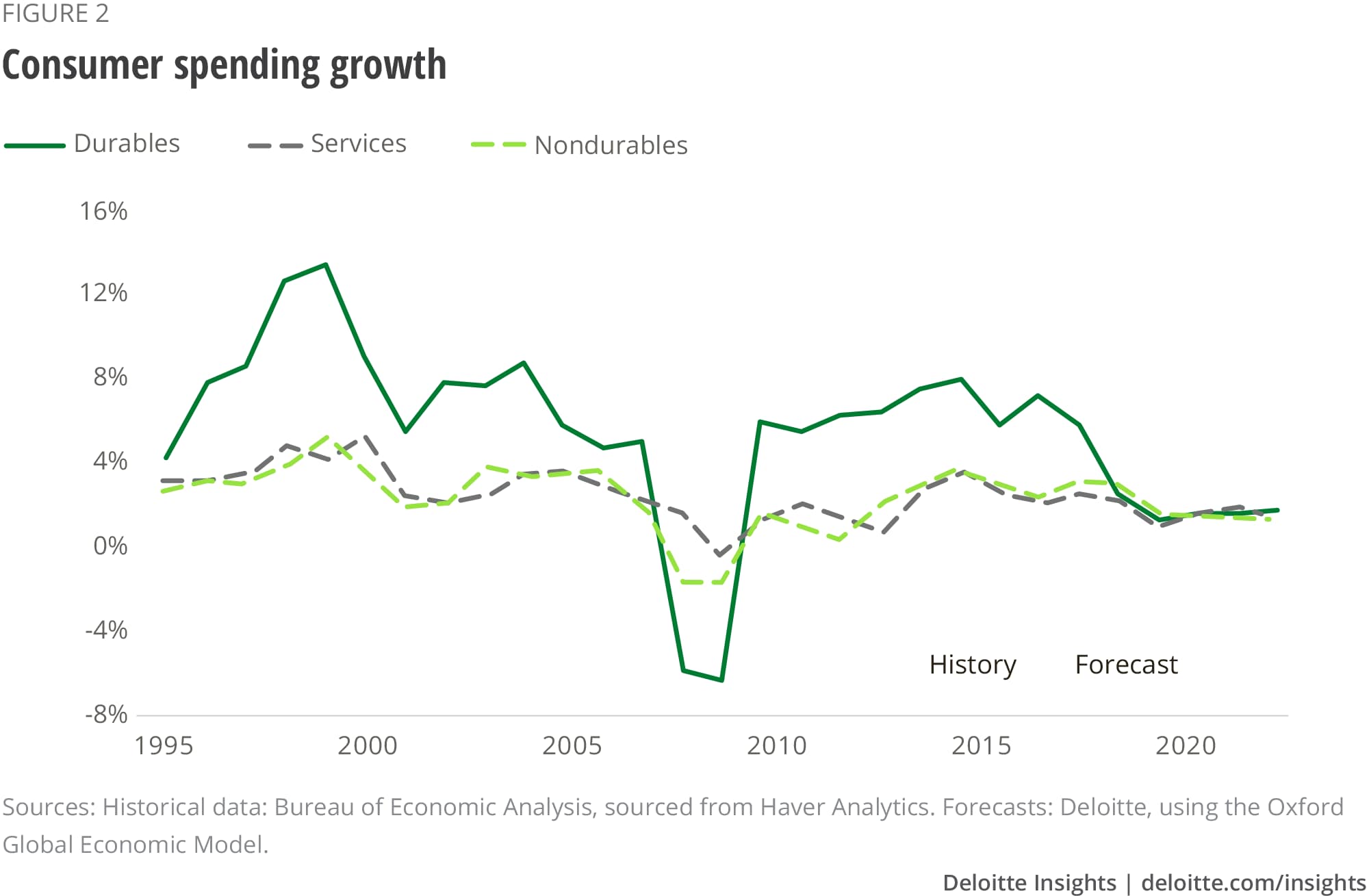

The household sector has provided an underpinning of steady growth for the US economy over the past few years. Even while business investment was weak, exports faced substantial headwinds, and housing stalled, consumer spending grew steadily.3 But that’s unsurprising, since job growth has been quite strong. Even with relatively low wage growth, those jobs have helped put money in consumers’ pockets, enabling households to continue to increase their spending. The continued steady (if modest) growth in house prices has helped, too, since houses are most households’ main form of wealth.

For all the daily speculation about how political developments might affect consumer choices when it comes to spending decisions, political noise seems to be just that—in the background—to consumers who seem focused on their own situations. As long as job growth holds up and house prices keep rising, consumer spending should remain strong. And the tax cut, while modest for most consumers, will likely bolster their confidence that they can safely spend. More importantly, the tax bill’s fiscal stimulus may tighten the job market even further. If wages begin to rise, consumer spending is likely to get a further boost.

The medium term presents a different picture. Many American consumers spent the 1990s and ’00s trying to maintain spending even as incomes stagnated. But now they are wiser (and older, which is another challenge, as many baby boomers face imminent retirement with inadequate savings4). That may constrain spending and require higher savings in the future.

One piece of good news is that government statisticians have found more savings. This year’s comprehensive revision of the national accounts included a substantial increase in income. As a result, we now know that the saving rate has remained about 6 percent since 2013 (the previous data showed a substantial decline in the rate, to about 3 percent). Most of the change involved upward revisions to asset income and proprietors’ income. This makes the household sector appear less vulnerable to another downturn.

Although American households seem to face fewer obstacles in their pursuit of the good life than just a few years ago, growing income inequality poses a significant challenge for the sector’s long-run health. For instance, low unemployment hasn’t alleviated many people’s economic insecurity: Four in 10 adults would be able to cover an unexpected US$400 expense only by borrowing money or selling something.5 For more about inequality, see Income inequality in the United States: What do we know and what does it mean?,6 Deloitte’s most recent examination of the issue.

Housing

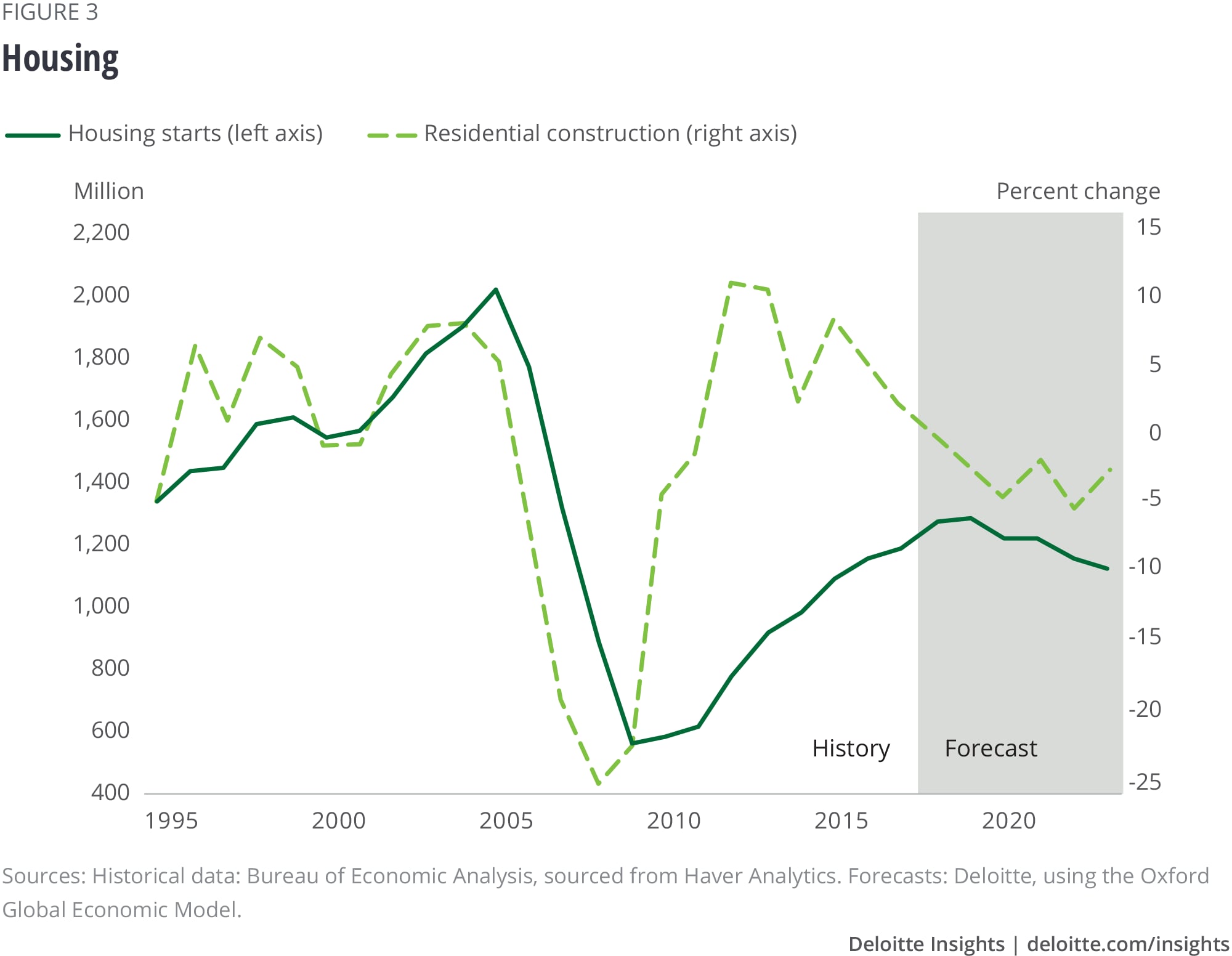

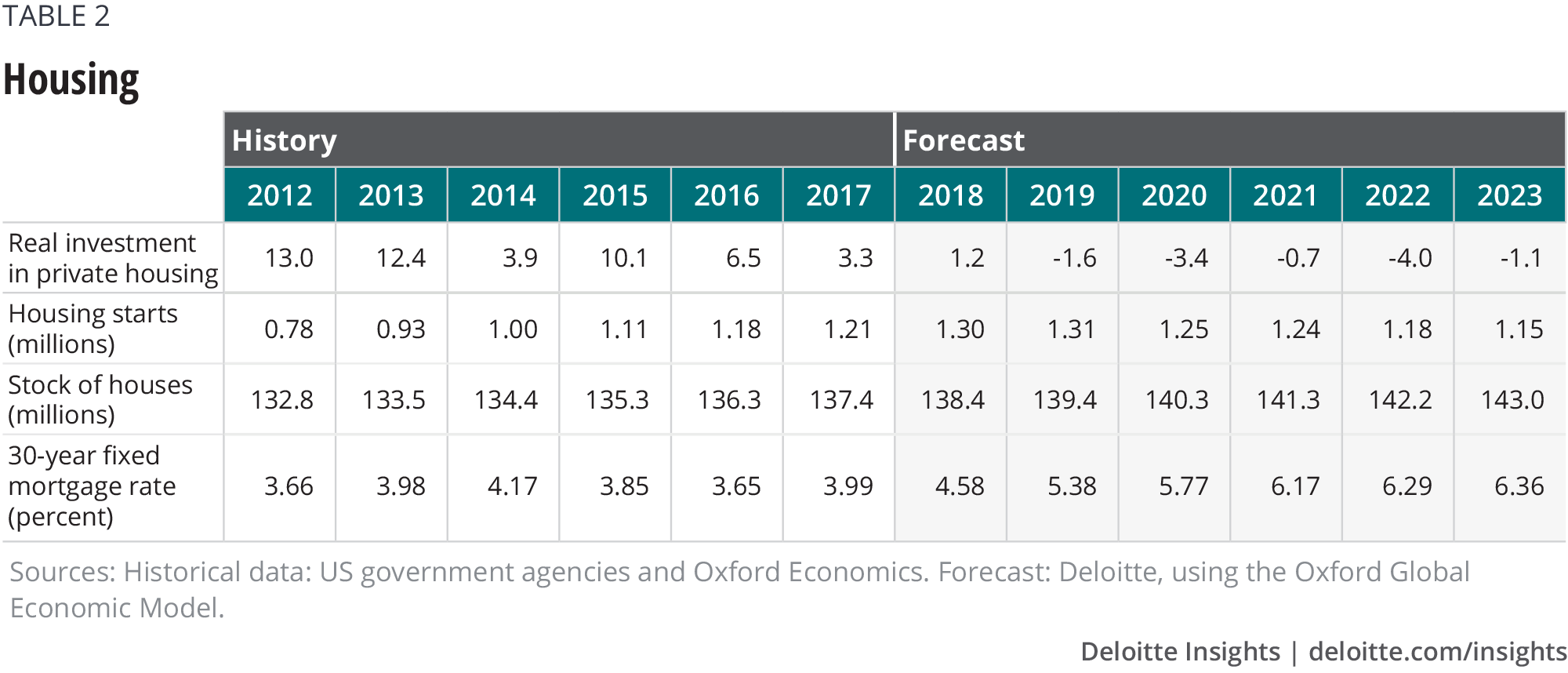

Every year, thousands of young Americans abandon the nest and start their own households. But more than usual stayed put after the recession: The number of households didn’t grow nearly enough to account for all the newly minted young adults. We expect that those young adults would prefer to live on their own and create new households; as the economy continues to recover, they will likely do exactly that, as previous generations have.

This should mean some positive short-run fundamentals for housing construction. Since 2008, the United States has been building fewer new housing units than the population would normally require—in fact, housing construction was hit so hard that the oversupply turned into an undersupply. But the hole is shallower than one might think, with several factors offsetting each other. Household size has stabilized after falling for several years. If it resumes falling—something to be expected as the population ages—the demand for housing would rise. The vacancy rate is still a bit higher than the historical norm, so there is some room for demand to be absorbed by filling vacant housing units.

Our best guess, based on a model of the housing market,7 is that there is room for a short-term boom in housing construction, to levels of perhaps 1.35 million units per year. A couple of years of housing starts at this level would fill any pent-up demand, leaving only the need for perhaps 1.1 million units, the number we estimate would meet demand in the medium term. This means that our forecast includes a small boom in the housing market, followed by several years of slowly declining construction. For the economy as a whole, that is not a major problem—housing remains a smaller share of GDP than it reached during the housing boom before the Great Recession.

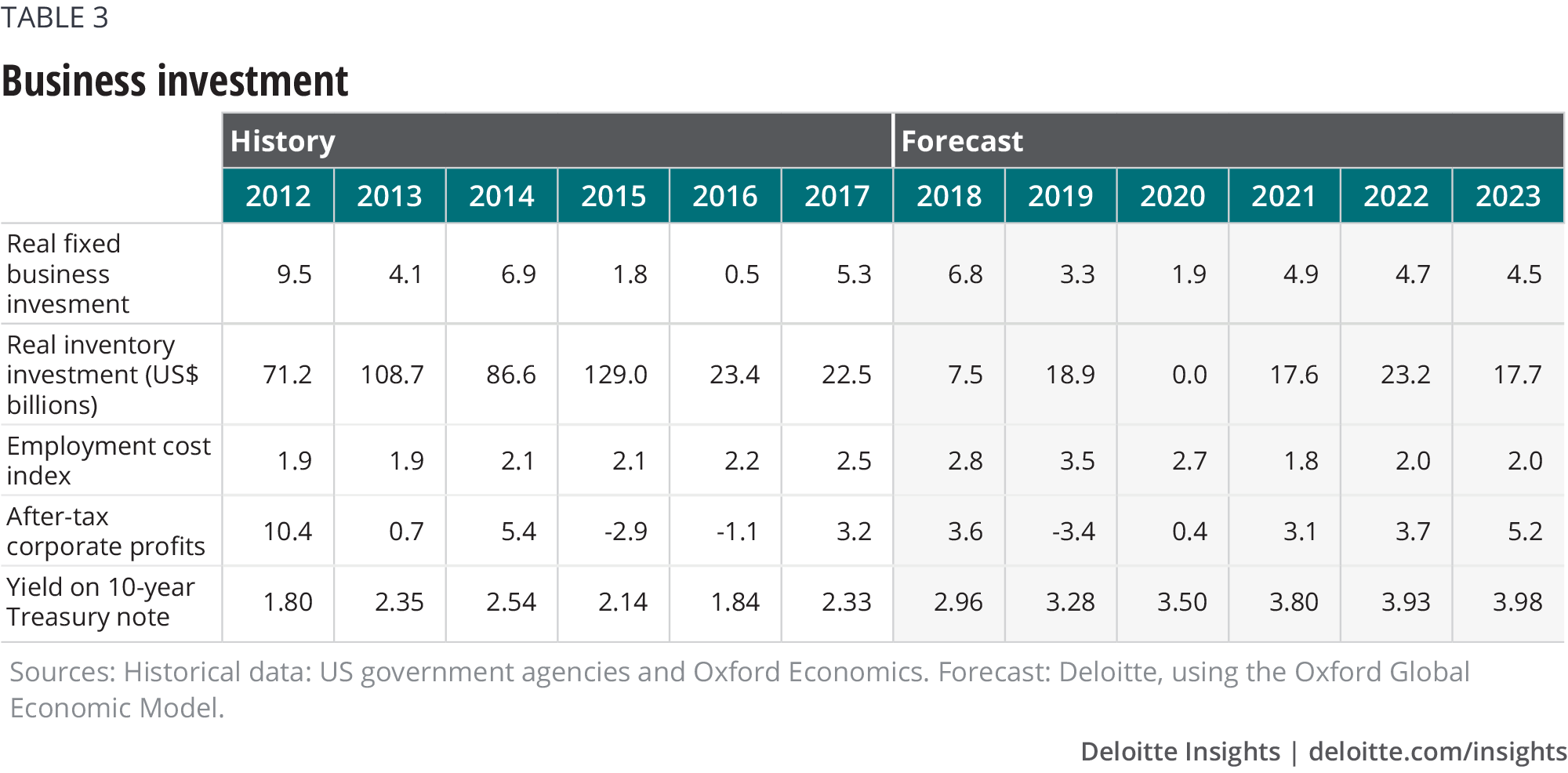

Business investment

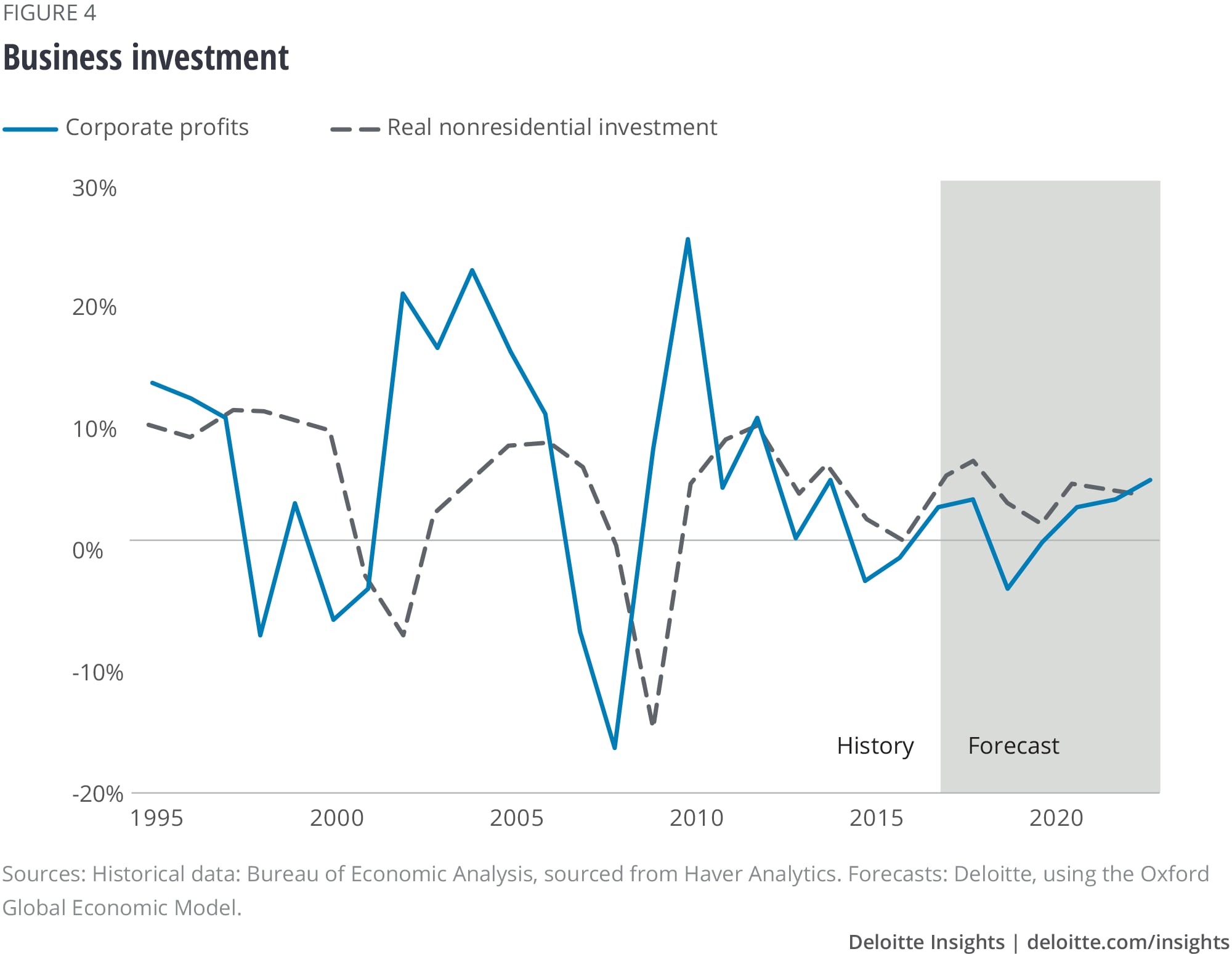

While businesses were just starting to reckon with the implications of the tax bill for investment, the US government introduced uncertainty from another direction—international trade.

The tax reform bill contained four main components that could affect business investment at the aggregate level.

- Congress cut the tax rate for businesses from 35 percent to 21 percent but eliminated a number of corporate tax breaks.8 Some companies will benefit more from the lower tax rates; others that depended on specific tax deductions may find their cost of capital to be higher than before the bill passed.

- The bill allows businesses to bring back earnings from foreign operations at lower tax rates (repatriation), which is unlikely to have a large impact on business spending—after all, if companies needed cash, they could have easily borrowed it, at historically low rates. In other words, the geographical location of the assets on the balance sheet is unlikely to drive corporate decision-making.

- A temporary provision allows for accelerated expensing of investments. Though the provision is phased out after 2022 (beyond our forecast horizon), there is some evidence that it will temporarily lift investment spending—possibly substantially.9

- The bill could increase corporate cash flow because the offsetting payments (from taxing repatriation of earnings and reducing corporate deductions) are less than the impact of lowering the tax rate. The tax reform bill essentially leaves more cash on corporate balance sheets, which may induce additional investment spending—or more stock buybacks and/or increased dividends.

The impact of the tax reform may be less than past experience suggests, however. Taxes affect investment decisions through the cost of capital, which also depends on interest rates and the depreciation rate. But the cost of capital has been at historic lows over the past decade, and many businesses have remained reluctant to take advantage to raise investment. So cutting the cost of capital further may have at best a modest impact. Our forecast assumes that additional investment spending adds several tenths of a percentage point to growth in 2018 and ’19.

However, the imposition of tariffs on a wide variety of goods—and foreign retaliation in the form of tariffs on American products—creates a large degree of uncertainty. Some CEOs may face a painful medium-term dilemma: deciding whether their businesses need to rebuild their supply chains. Industries such as automobile production have developed intricate networks across North America and are reaching into Asia and Europe, based on the longstanding assumption that materials and parts can be moved across borders with little cost or disruption. There is some evidence that a substantial number of business leaders are beginning to think about postponing investment: The Atlanta Fed found in early August that some 30 percent of manufacturing firms are reassessing capital expenditure plans because of uncertainty about tariffs.10

Business investment plays a key role in differentiating between Deloitte’s baseline, slow-growth, and productivity bonanza scenarios. If business spending does indeed fall off because of policy uncertainty, the likelihood of the slow-growth scenario would substantially increase.

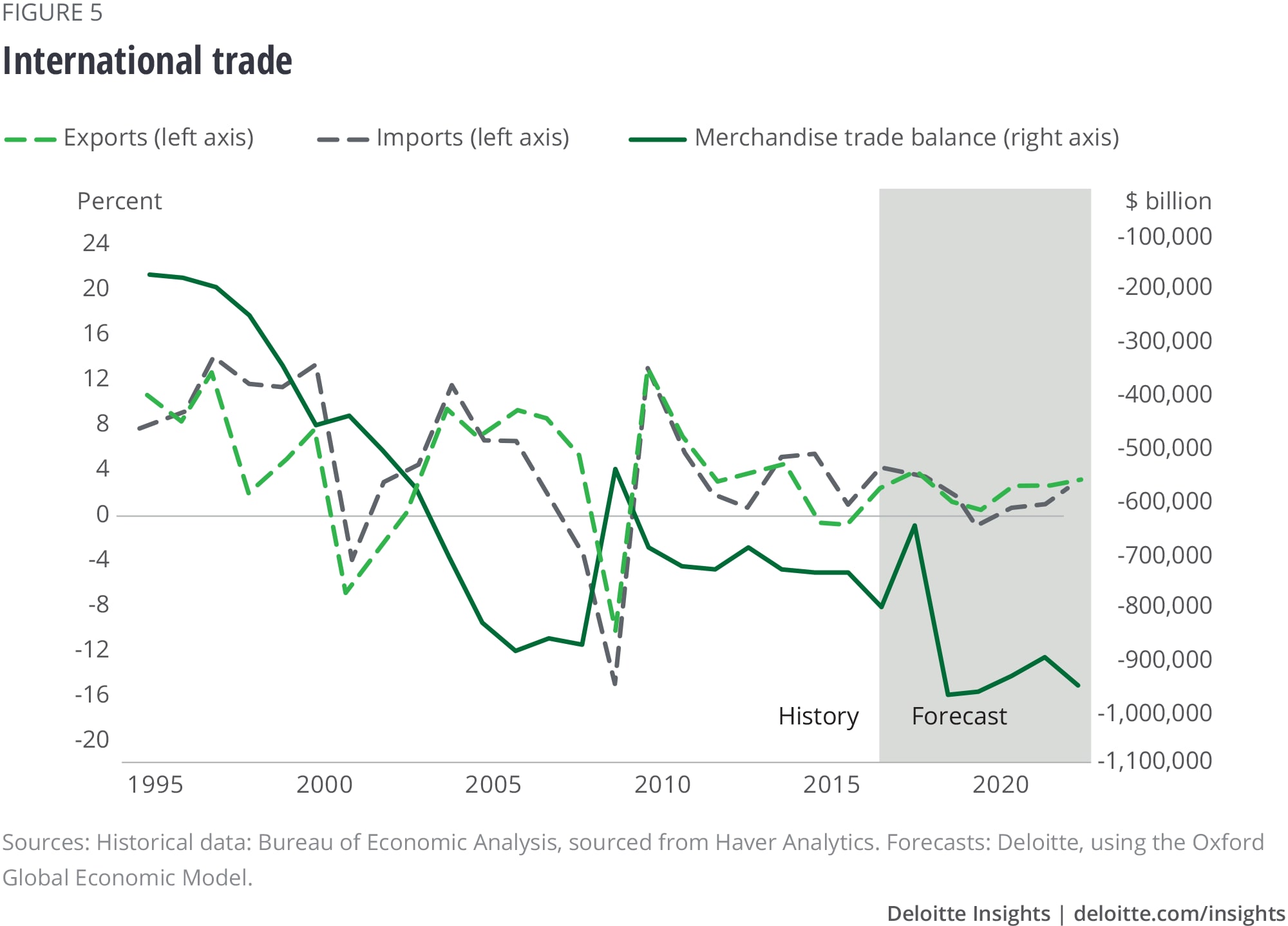

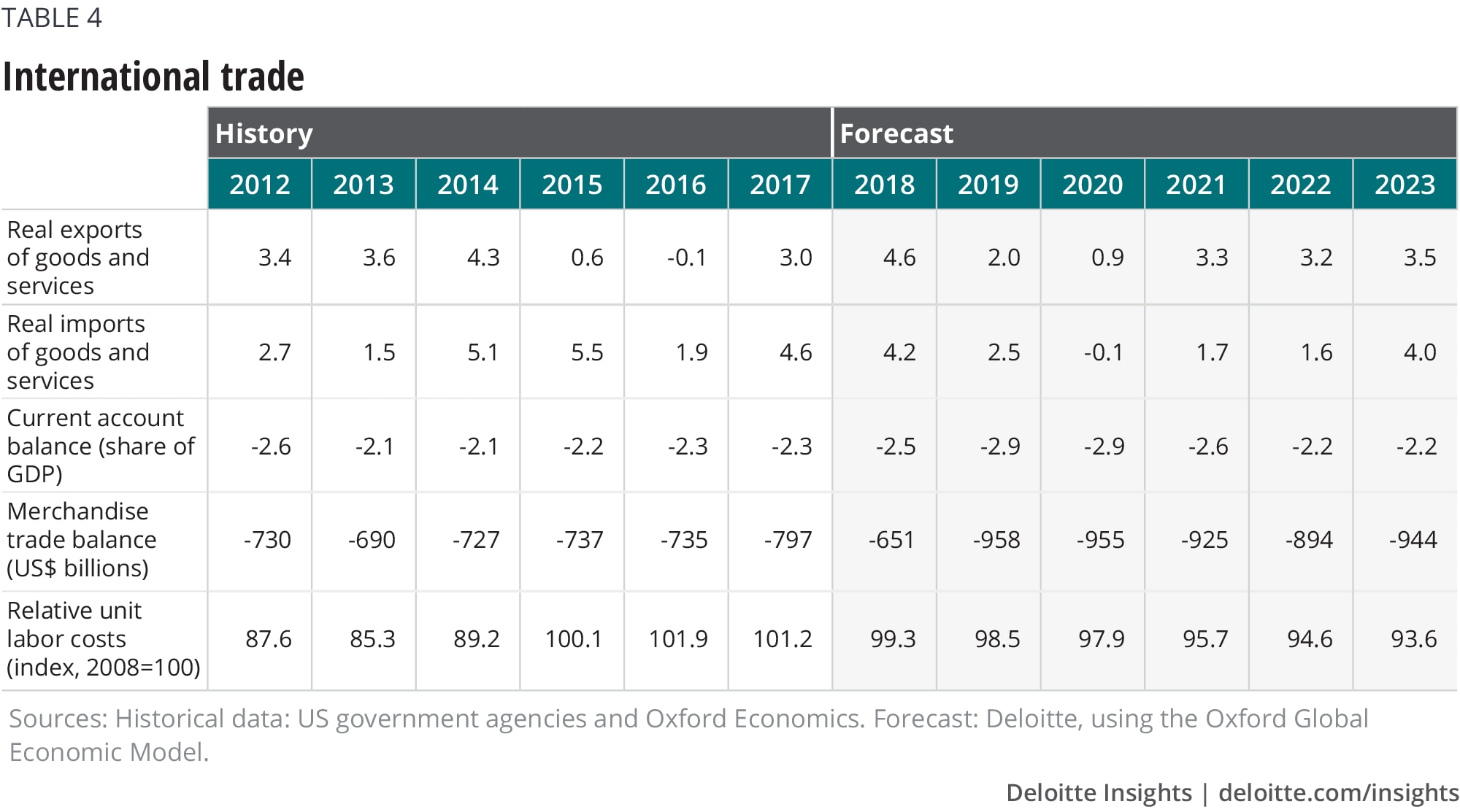

Foreign trade

Over the past few decades, business—especially manufacturing—has taken advantage of generally open borders and cheap transportation to cut costs and improve global efficiency. The result is a complex matrix of production that makes the traditional measures of imports and exports somewhat misleading. For example, in 2017, 37 percent of Mexico’s exports to the United States consisted of intermediate inputs purchased from . . . the United States.11

Recent events appear to be placing this global manufacturing system at risk. The United Kingdom’s increasingly tenuous post-Brexit position in the European manufacturing ecosystem,12 along with ongoing negotiations to tweak parts of the North American Free Trade Agreement,13 may slow the growth of this system or even cause it to unwind.

But the biggest challenge now facing the global trading system is the imposition of tariffs and retaliatory tariffs. The process began with US tariffs on steel and aluminum and now encompasses a wide variety of US imports from China as well as Chinese imports from the United States. The United States has also threatened to put a 20 percent tariff on automobile imports from the European Union.14 Additional tariffs are certainly possible.

Whether this qualifies as a “trade war” is a semantic question—the real issue is the uncertainty about the tariffs and the US government’s goals in imposing the tariffs. White House trade adviser Peter Navarro argues that the tariffs are necessary to reduce the US trade deficit and to help the United States retain industries such as steel production for strategic reasons.15 This suggests that tariffs in strategic industries could be permanent. But Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has stated that the goal is to force US trading partners to lower their own barriers to American exports.16 That suggests that the administration intends the tariffs to be a temporary measure to be traded for better access to foreign markets.

The lack of clarity in the administration’s stated objectives with regard to tariffs adds to the overall uncertainty involved with the tit-for-tat actions that began in the spring. In the short run, uncertainty about border-crossing costs may reduce investment spending. Businesses may be reluctant to invest when facing the possibility of a sudden shift in costs. Deloitte’s slow-growth scenario assumes that the impact is large enough to affect overall business investment.

The challenge that companies face is that a significant change in border-crossing costs—as would occur if the United States withdrew from NAFTA or made tariffs on Chinese goods permanent—could potentially reduce the value of capital investment put in place to take advantage of global goods flows. Essentially, the global capital stock could depreciate more quickly than our normal measures would suggest. In practical terms, some US plants and equipment could go idle without the ability to access foreign intermediate products at previously planned prices.

With this loss of productive capacity would come the need to replace it with plants and equipment that would be profitable at the higher border cost. We might expect gross investment to increase once the outline of a new global trading system becomes apparent.

In the longer term, a more protectionist environment will likely raise costs. That’s a simple conclusion to be drawn from the fact that globalization was largely driven by businesses trying to cut costs. How those extra costs are distributed depends a great deal on economic policy—for example, central banks can attempt to fight the impact of lower globalization on prices (with a resulting period of high unemployment) or to accommodate it (allowing inflation to pick up).

The current account is determined by global financial flows, not trade costs.17 Any potential reduction in the current account deficit is likely to be largely offset by a reduction in American competitiveness through higher costs in the United States, lower costs abroad, and a higher dollar. All four scenarios of our forecast assume that the direct impact of trade policy on the current account deficit is relatively small.

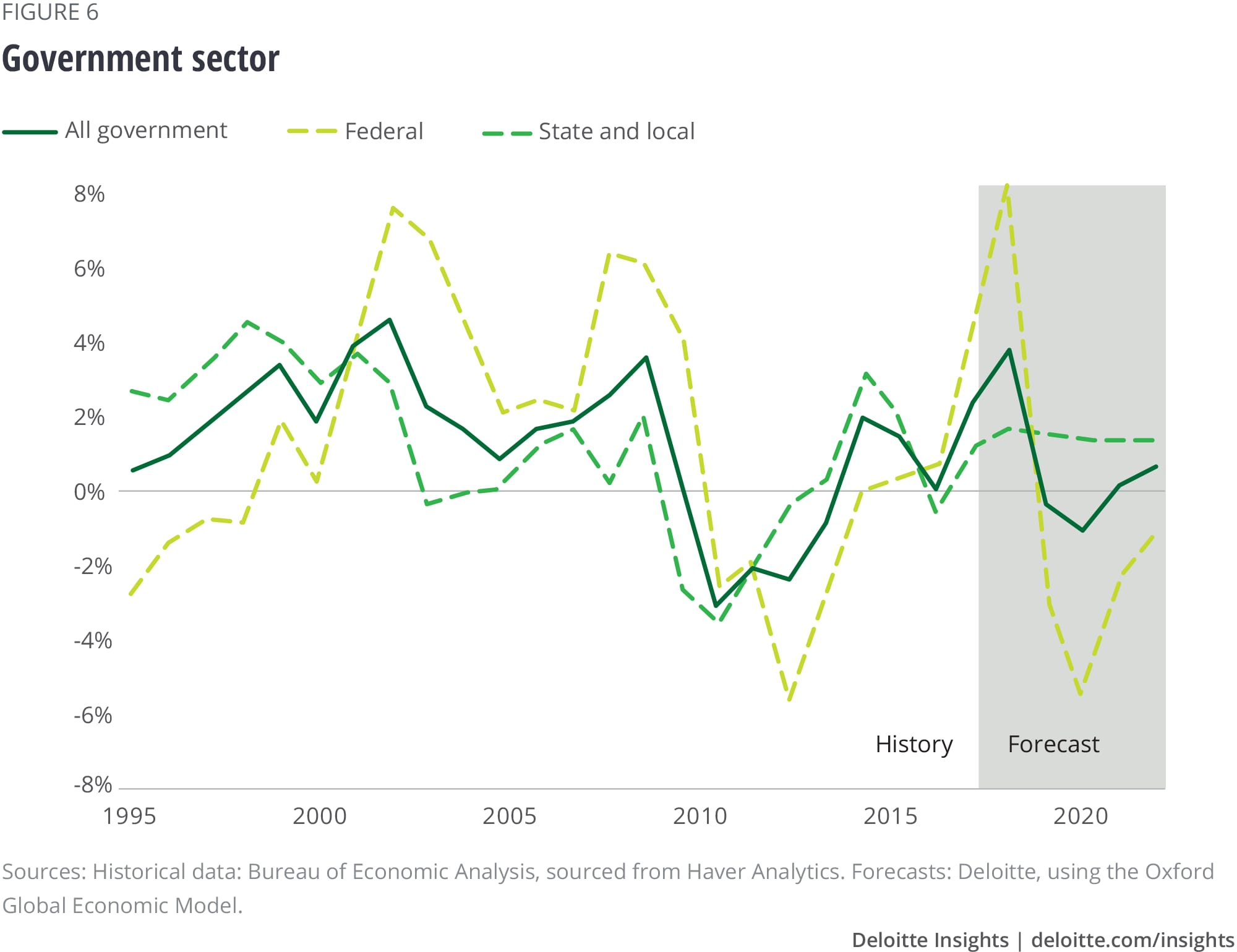

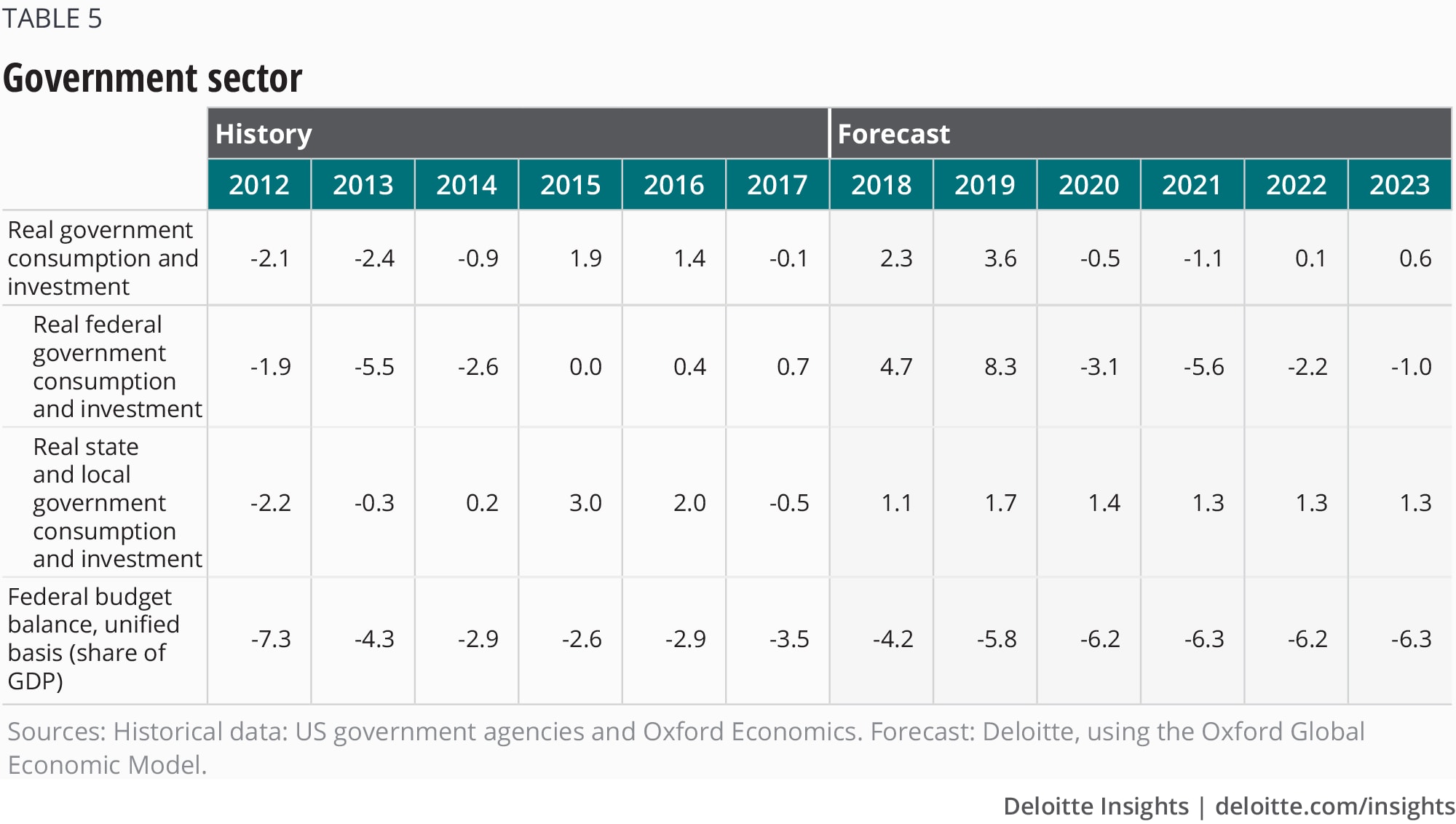

Government

Government provides an unusual source of volatility in the Deloitte forecast. Normally, changes in public-sector spending and tax collections are smooth and relatively modest. However, the tax bill passed in late 2017 and the budget bill passed in early 2018 together created a large stimulus—over 2.0 percent of GDP, by Deloitte calculations, in 2019. However, with no certainty that the large spending increase will continue, it is likely that government spending will start falling in late 2019 and through 2020. This drag on the economy will be large enough to slow growth substantially. The Deloitte baseline forecast sees GDP growth at just 0.7 percent in 2020, substantially below potential.

The tax bill’s long-run impact on the economy’s capacity remains a matter of debate, with estimates ranging from no real change after a decade (Tax Policy Center) to 2.8 percent, or almost 0.3 percentage points annually (Tax Foundation).18 In this forecast’s five-year horizon, the supply-side impact is likely too small to be noticeable.

Prospects for an infrastructure spending package appear unlikely at this point in the legislative calendar. Congress has relatively little time to pass funding bills and confirm appointees before the 2018 elections. Our baseline assumes no infrastructure plan, while the productivity bonanza scenario assumes some additional government spending as well as additional productivity from these investments in the medium and long runs.

After years of belt-tightening, many state and local governments are no longer actively cutting spending. However, many state budgets remain constrained by questions around the effects of new federal tax policy19 and the need to meet large unfunded pension obligations,20 so state and local spending growth will likely remain low over this forecast’s five-year horizon.

Pressure is building for increased spending in education, as evidenced by the recent public teacher protests in several states.21 With education costs accounting for about a third of all state and local spending, a significant upturn in this category could create some additional stimulus—or require an increase in state and local taxes.

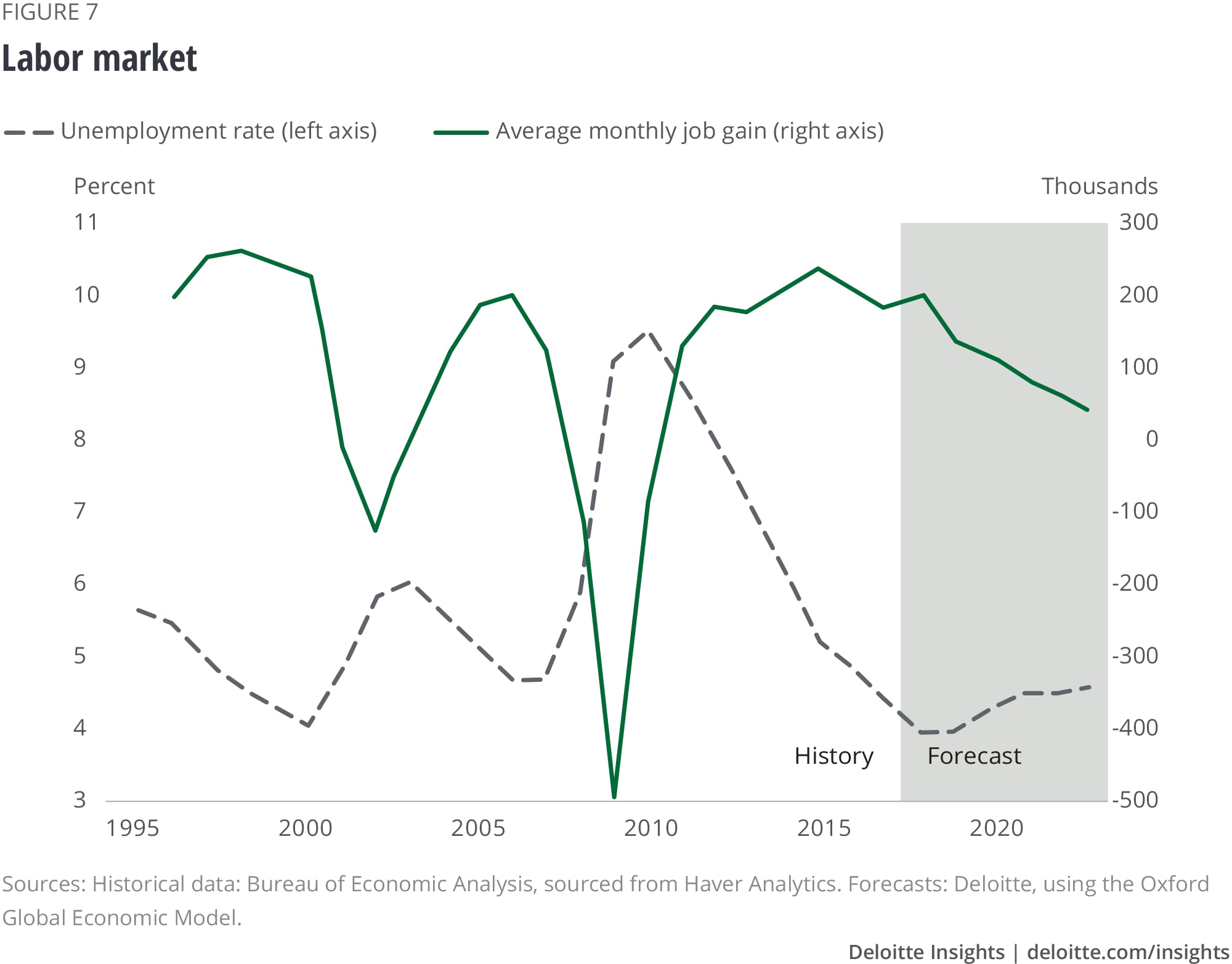

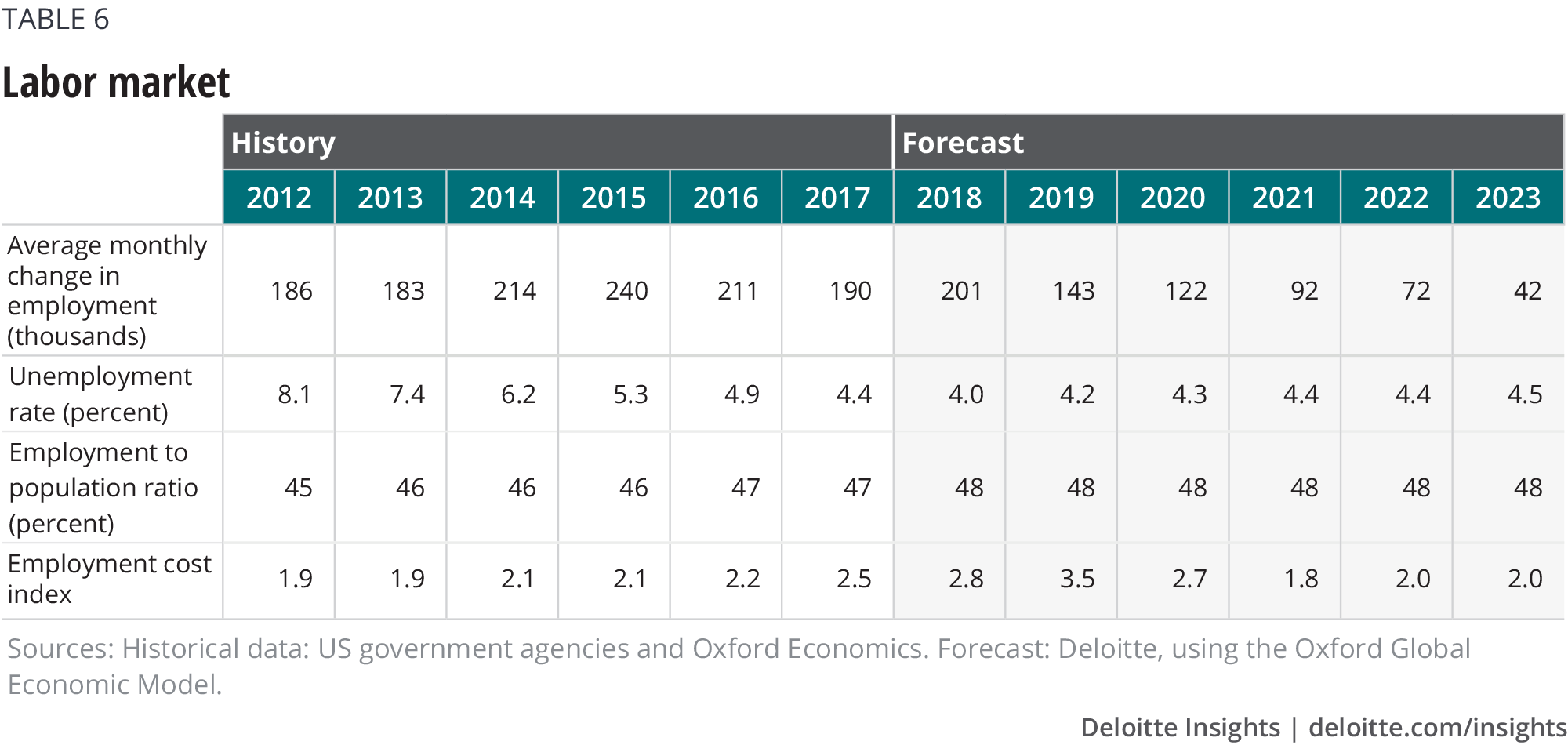

Labor markets

If the American economy is to effectively produce more goods and services, it will need more workers. Many potential employees remain out of the labor force, having left in 2009, when the labor market was challenging. But they are returning. The labor force participation rate for prime-age workers has been rising since the middle of 2015 and is, as of June, over 80 percent.22 But there are still more workers who can be enticed back into the labor market as conditions improve, and our baseline forecast reflects that possibility.

Meanwhile, the labor force participation rate for over-65s has flattened out. It’s still much higher than the historical average—and it is certainly possible that, with better labor market conditions, more over-65s can be enticed back into the labor force as well.

But a great many people are still on the sidelines and have been out of steady employment for years—long enough that their basic work skills may be eroding.23 Are those people still employable? So far, the answer has been “yes,” as job growth continues to be strong without pushing up wages. Deloitte’s forecast team remains optimistic that improvements in the labor market will prove increasingly attractive to potential workers, and labor force participation is likely to continue to improve accordingly.

Despite this, demographics are slowing the growth of the population in prime labor force age. As boomers age, lagging demographic growth will help slow the economy’s potential growth. That’s why we foresee trend growth just a bit above 1.5 percent by 2021: Even with an optimistic view about productivity, we expect that slow labor force growth will eventually be felt in lower economic growth.

Immigration reform might have a marginal impact on the labor force. According to the Pew Research Center, undocumented immigrants make up about 5 percent of the total American labor force.24 Removal of all such workers would clearly have a significant, disruptive impact on the labor force and on the economy: Any mass removal of undocumented workers could create labor shortages in certain industries, such as agriculture, in which some 17 percent of workers are unauthorized,25 and construction, in which an estimated 13 percent of workers are unauthorized.26 But it would likely have little significant impact at the aggregate level.

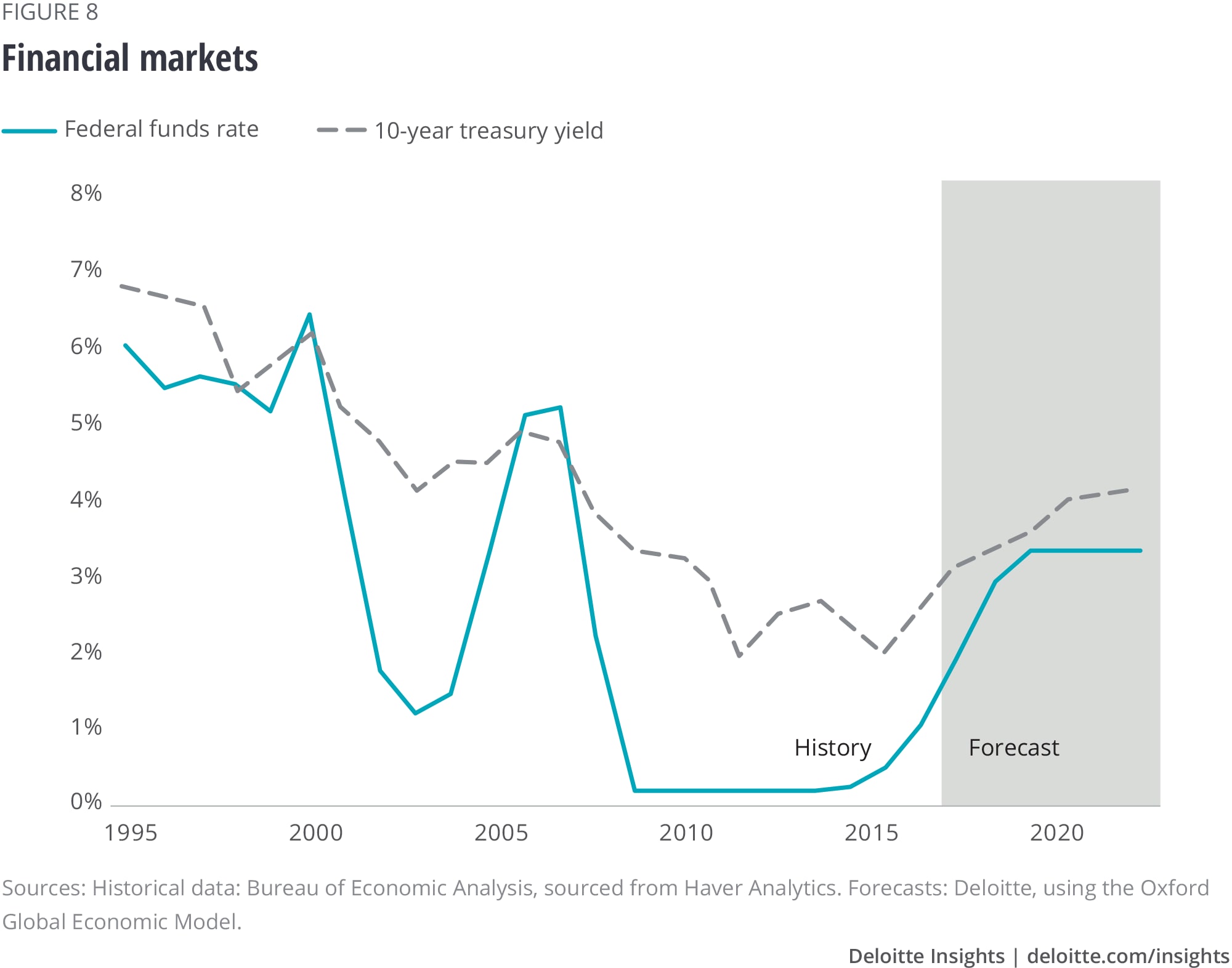

Financial markets

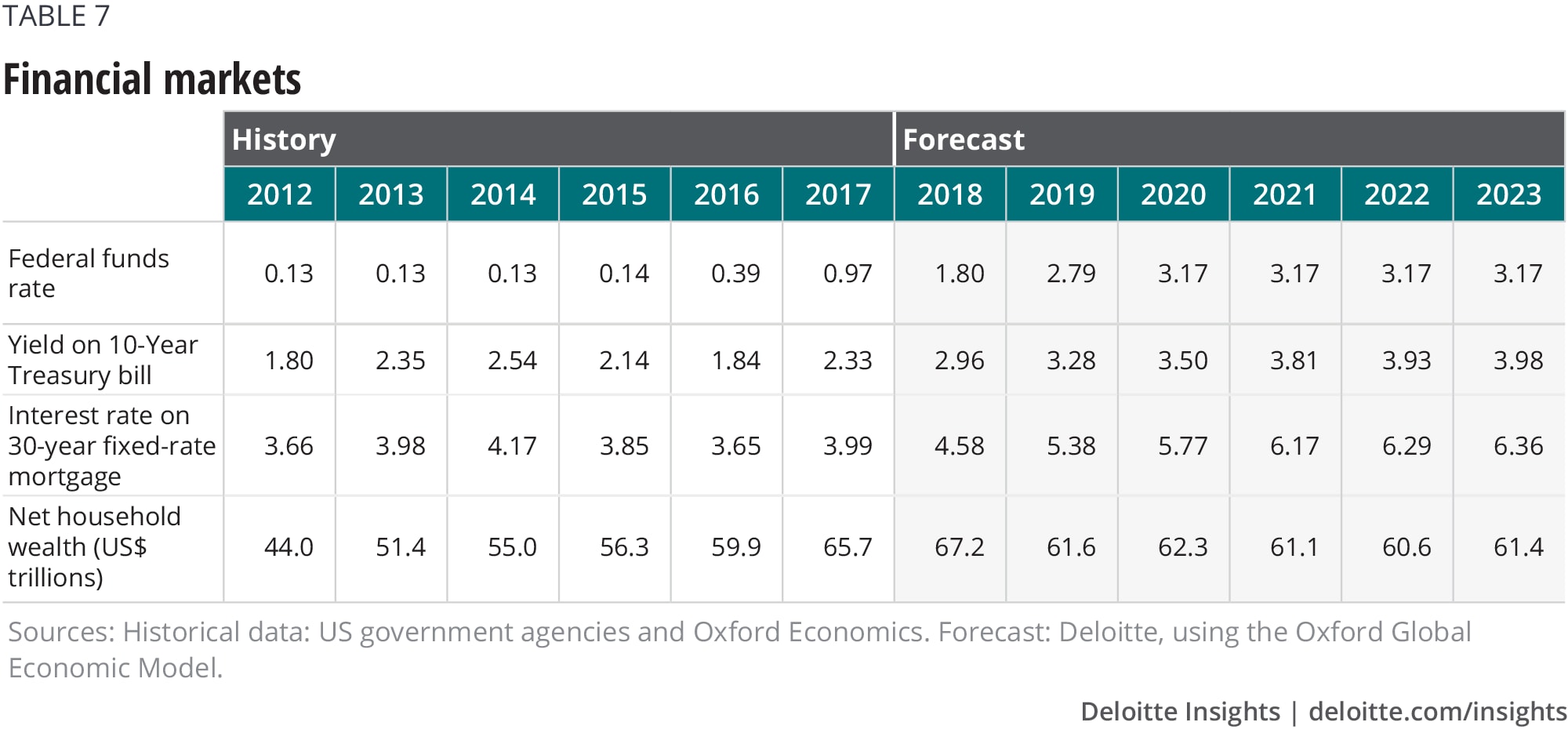

Interest rates are among the most difficult economic variables to forecast because movements depend on news—and if we knew it ahead of time, it wouldn’t be news. The Deloitte interest rate forecast is designed to show a path for rates consistent with the forecast for the real economy. But the potential risk for different interest rate movements is higher here than in other parts of our forecast.

The forecast sees both long- and short-term interest rates headed up—maybe not this week, or this month, but sometime in the future. Fed officials are clearly concerned about the possibility of the economy overheating: The January Federal Open Market Committee minutes noted that “participants ... anticipated that the rate of economic growth in 2018 would exceed their estimates of its sustainable longer-run pace.” This was before Congress passed the large spending stimulus in February. Any signs of incipient acceleration in inflation will likely elicit a strong Fed response.

We expect the Fed to continue to hike short-term interest rates at every second FOMC meeting for the rest of 2018 and for all of 2019, and to continue to let its inventory of short-term assets shrink at a slow rate. Our estimate of the Fed’s view of the “neutral rate”—the rate that is consistent with full employment and stable inflation—stands at 3.2 percent. However, some Fed officials are discussing a lower neutral rate. FOMC members’ central estimate for the longer-run value of the Fed funds rate is, in fact, 2.8 to 3.0 percent,27 so our forecast is a little higher than the Fed’s.

As the economy approaches full employment and the possibility of higher inflation increases, long-term interest rates will rise as well—and perhaps even rise faster. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s part of the “return to normal” that the US economy is experiencing.

Many forecasters believe that this “normal” rate will be around 3.5 percent. At a Fed funds rate of around 3.0 percent, that would suggest an equilibrium value of the spread between the Fed funds rate and the 10-year note yield of just half a percent. That’s historically very low. The average spread over the postwar period has been about 1.0 percent, and that includes the time during recessions when the spread shrinks to almost nothing or even goes negative. The normal spread is therefore certainly above 1.0 percentage point, implying that a 3.0 percent fund rate would be consistent with a 10-year Treasury yield over 4.0 percent. Between 2002 and ’06, the spread averaged almost 2.0 percent. If the spread moves that high, long-term rates could easily hit 5.0 percent or more.

Prices

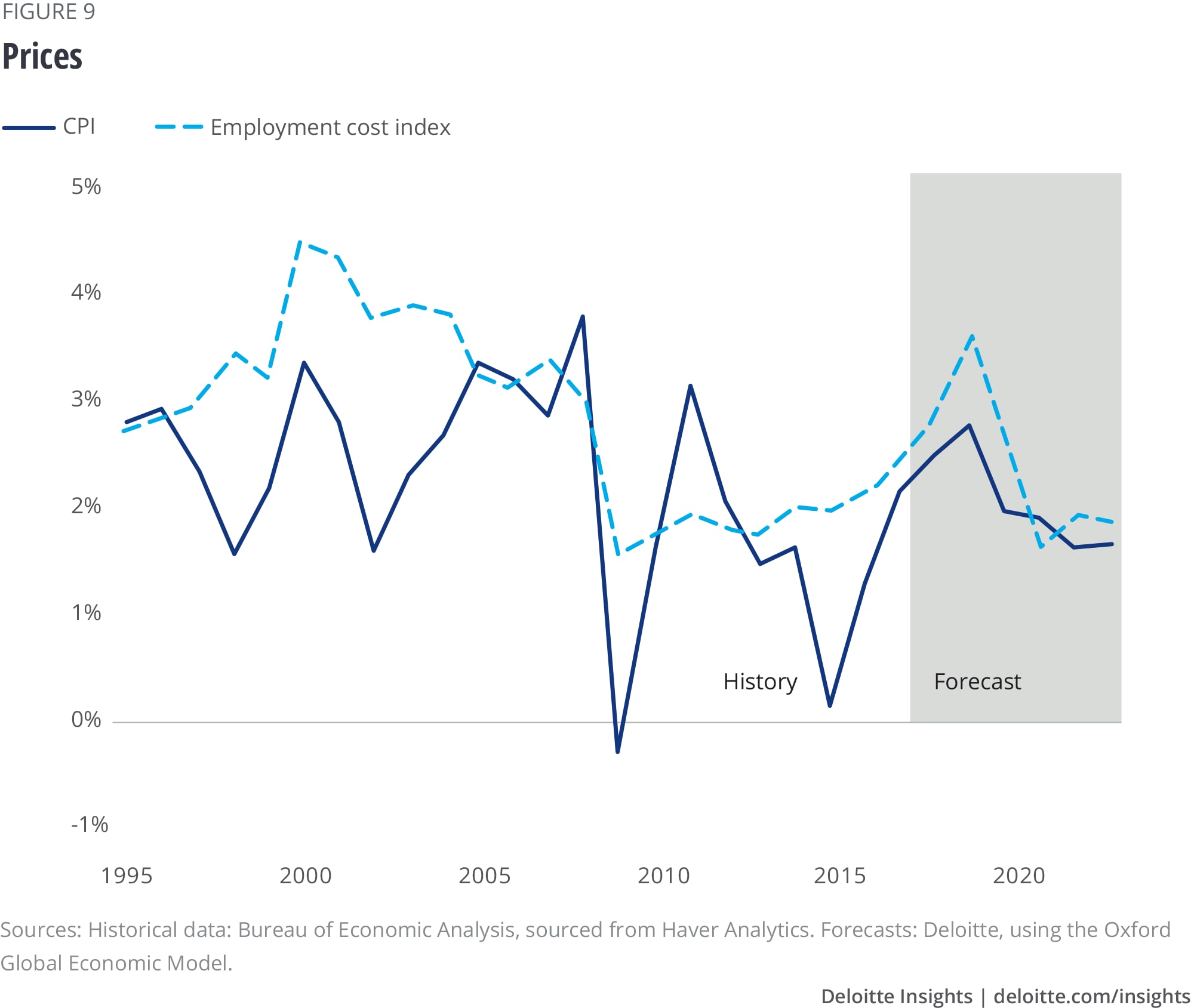

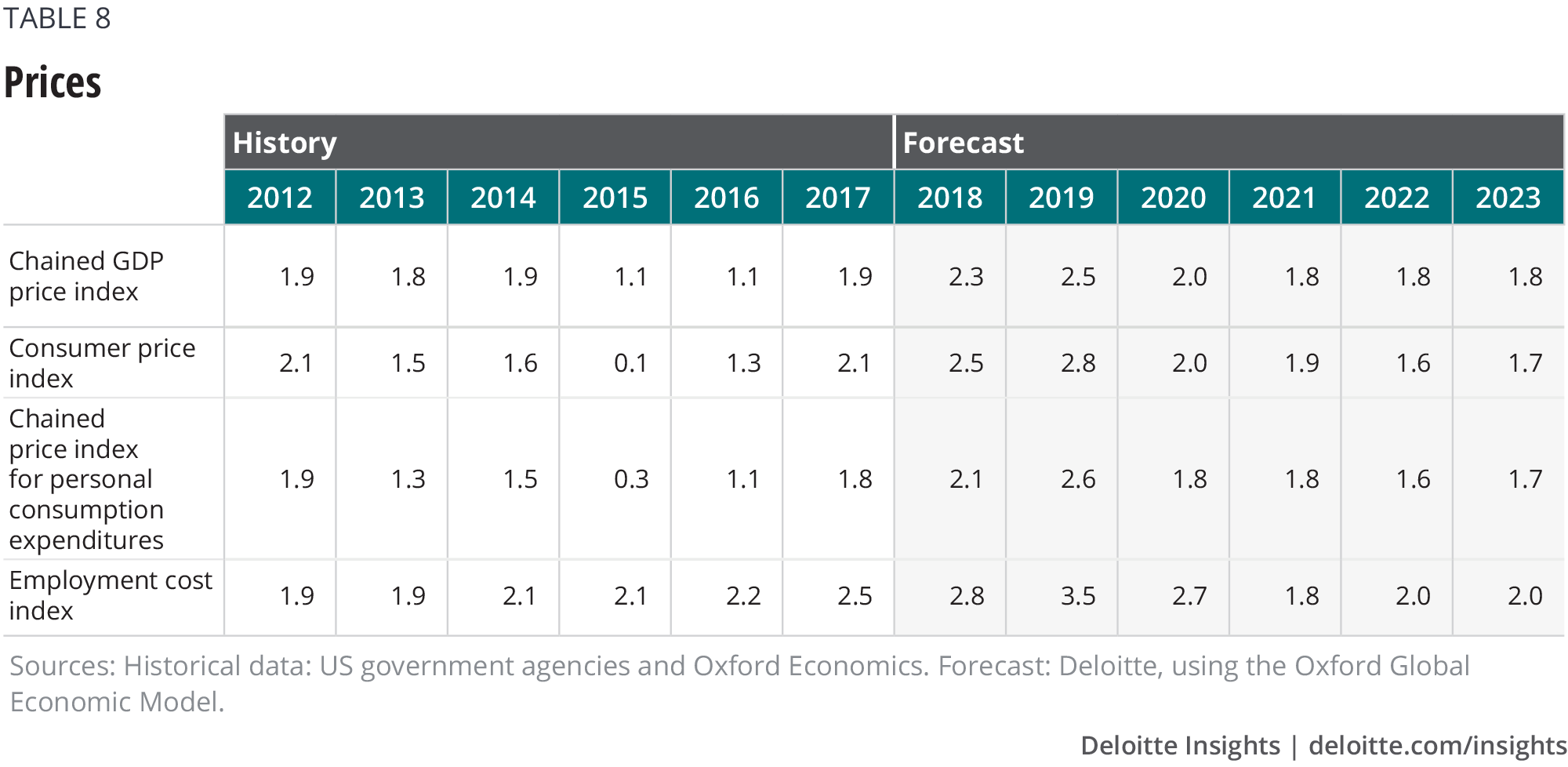

It’s been a long time since inflation has posed a problem for American policymakers. Could inflation break out as the economy reaches full employment? Economists are increasingly wondering about this, as it becomes evident that something is amiss in the standard inflation models. These models posit that, since labor accounts for about 70 percent of business costs, the state of the labor market should drive overall inflation. US labor markets appear to be tightening, but wages have failed to rise accordingly or even keep pace with inflation.28 As long as businesses don’t face increasing costs, it’s hard to see what would drive a sustained rise in goods and services prices.

But it’s also quite possible that the economy simply hasn’t hit full employment. Despite unemployment dipping below 4.0 percent, the labor force participation rate for prime-age workers remains about two points below the rate before the financial crisis. Two percent of the prime working-age population suggests that about 4 million more people could be enticed into the labor force under the right conditions. Whether those people are really available is unclear, and economists are debating the issue fiercely.29 The combination of low labor-cost growth and continued high employment growth suggests that people are indeed being enticed back into the labor market.

At some point, however, the combination of the tax cut and spending increase could create some shortages in both labor and product markets and, as a result, some inflation. And tariffs are something of a wild card. So far, most of the tariffs have been on intermediate products, and the price increases from these will be relatively modest and take time to work through the system. A large increase in tariffs on consumer goods would likely cause a fast, one-time rise in consumer prices, particularly for products such as apparel and furniture. Interpreting inflation data under those circumstances could be tricky. And if that rise sparks wage hikes to maintain real wages—a possibility at current unemployment rates—inflation could indeed tick up.

A return to 1970s-style inflation is about as likely as polyester leisure suits coming back into style. But it would not be surprising in these circumstances to see the core CPI rise to above 2.5 percent. Our forecast expects timely Fed action to prevent inflation from rising too much, but the price (of course) is higher interest rates.

Appendix