Transform to React: Climate Policy in the New World Order

The policy environment is shaping up

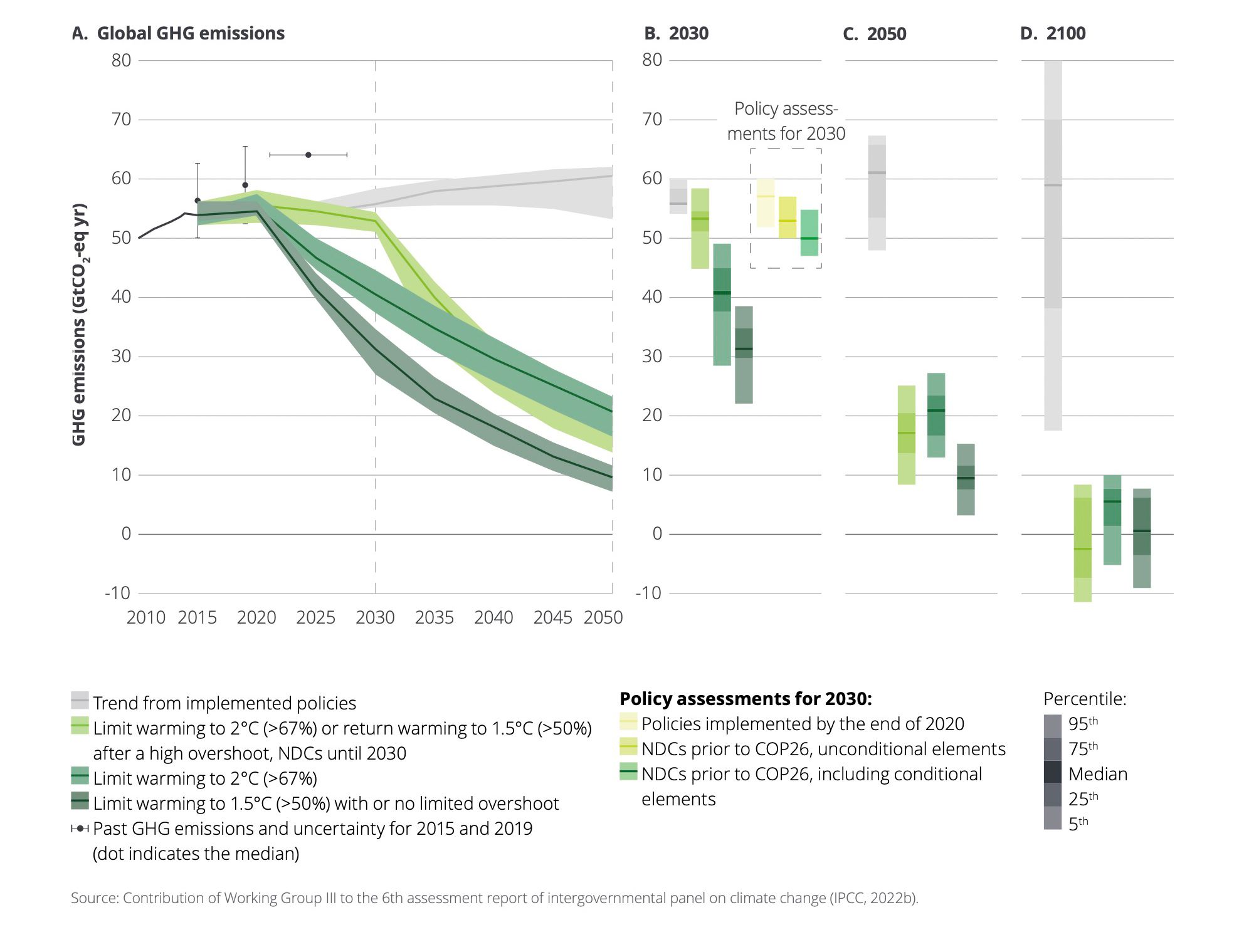

Following the Paris Agreement, 125 countries that are home to 1/3 of the world’s population and more than half of the world’s GDP have set the goal of climate neutrality by 2050 or before. Although the specification and legal status of the targets differ among countries, they have put energy transition at the top of policy-makers’ agendas around the world. CO2 and other GHG pricing, renewable support schemes and quota obligations are some of the most common policy instruments being deployed by governments to stay in-line with climate goals.

Many drivers are in place

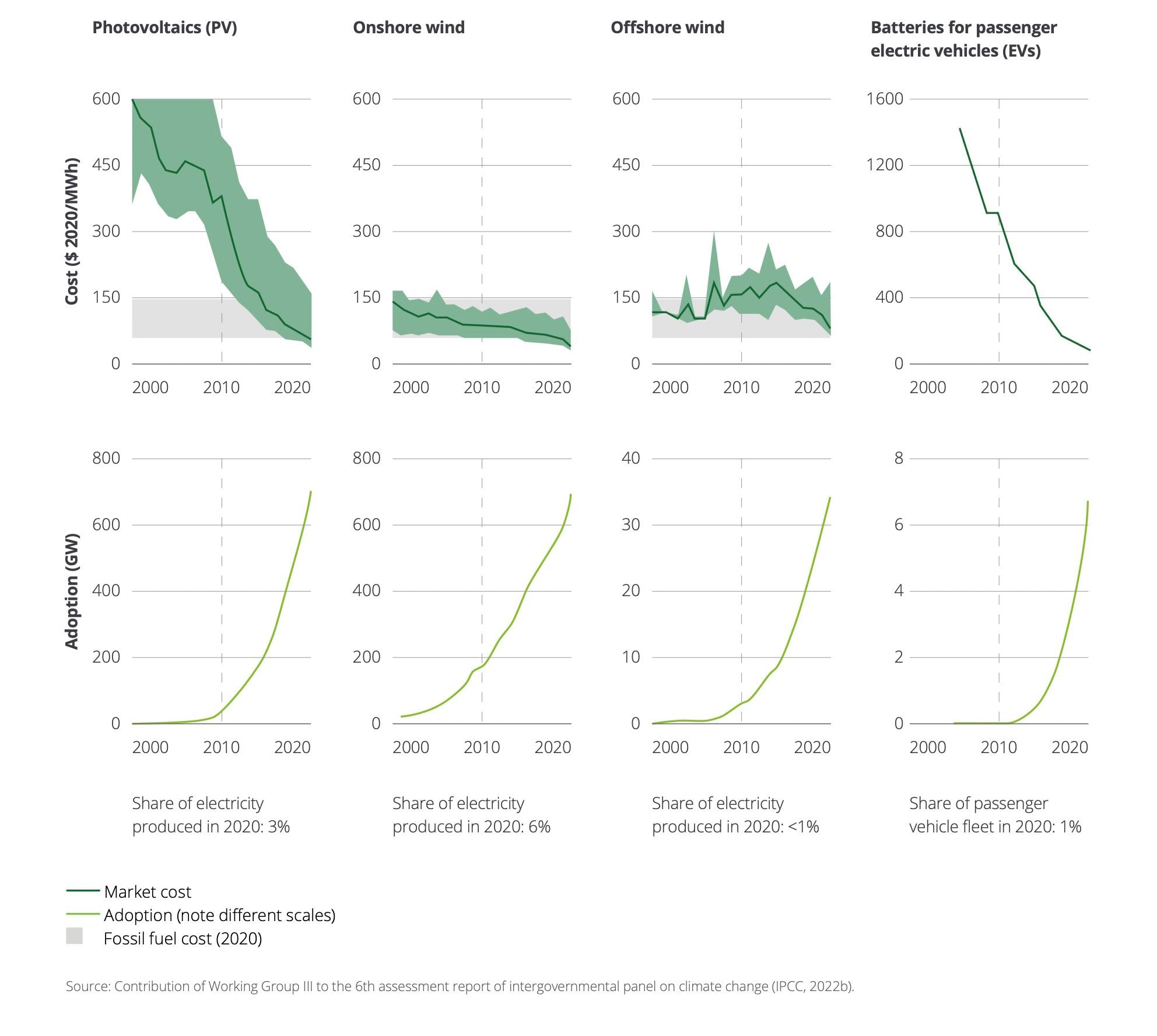

Transition of the energy system and decarbonization of hard-to-abate sectors such as industry and transport require implementation of clean technologies at scale. Some of these technologies, especially for renewable energy, have made rapid progress, with steep cost reduction and efficiency improvement, while others are still at the early stage of development. These breakthroughs have come from both determined private sector focus and policy incentives for investments in such technologies. For instance, the cost of electricity generation from solar PV fell by almost 90%, while onshore wind power costs have been cut 70% over the last 10 years. And thanks to the strong growth of electric vehicle sales, the cost of Li-Ion batteries has dropped by 90% during the same period. These trends are expected to continue as installed capacity increases, also for other energy transition technologies like electrolysers for renewable hydrogen supply.

From a macroeconomic perspective, growing international trade and direct foreign investment, have created a more favorable environment for capital-intensive investments since the early 2000s. Although this increase in capital from the private sector has been directed at developing countries and has contributed to reducing inequalities, it has also led to increased emissions (from 4.3GtCO2 in 1990 to 7.8GtCO2 in 2008). Despite increased global CO2 emissions, globalization has also made clean technologies accessible at ever lower costs, underpinning the growing deployment of these technologies. Global investment in clean technologies increased from US$60 billion to US$524 billion between 2005 and 2020. Nevertheless, investment in these technologies remains insufficient to stay in line with the 1.5°C target. Planned investments in clean energy technologies account for US$98 trillion through 2050, while a 1.5°Compatible investment pathway would require an additional US$33 trillion over the same period. The capital to deliver such massive investment exists, but both public and private resources will need to be mobilized.

Efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of the value chain have gained significant attention lately, thanks largely to policy instruments, but also to consumer preferences for cleaner goods. The policy instruments vary, depending on sector, from obligations to quotas, from taxes to financial support schemes, etc. In the energy sector, for instance, these support mechanisms include feed-in tariffs and feed-in premiums, obligations such as renewable quotas, and fines and additional taxes such as CO2 pricing schemes. These policy mechanisms have led to parallel financial markets, such as for guarantees of origin and emission quotas. Thanks to these policies and the development of corresponding markets, many more stakeholders participate in climate-related markets. This targets and reduces not only direct CO2 emissions, but the entire value-chain emissions of goods.

Electrification and renewables are key to achieving climate goals

Electrification and variable renewables, mainly wind and solar PV, are set to play a key role in future low carbon energy systems. Variable renewables are weather-dependent and create the need for electricity storage solutions, such as batteries. More renewables imply new challenges, such as greater price volatility, coordination of infrastructure investments, and local acceptance of decentralized installations. Moreover, the decarbonization of industry implies replacement of much of fossil feedstocks and energies with renewable and low-carbon hydrogen or biomass.

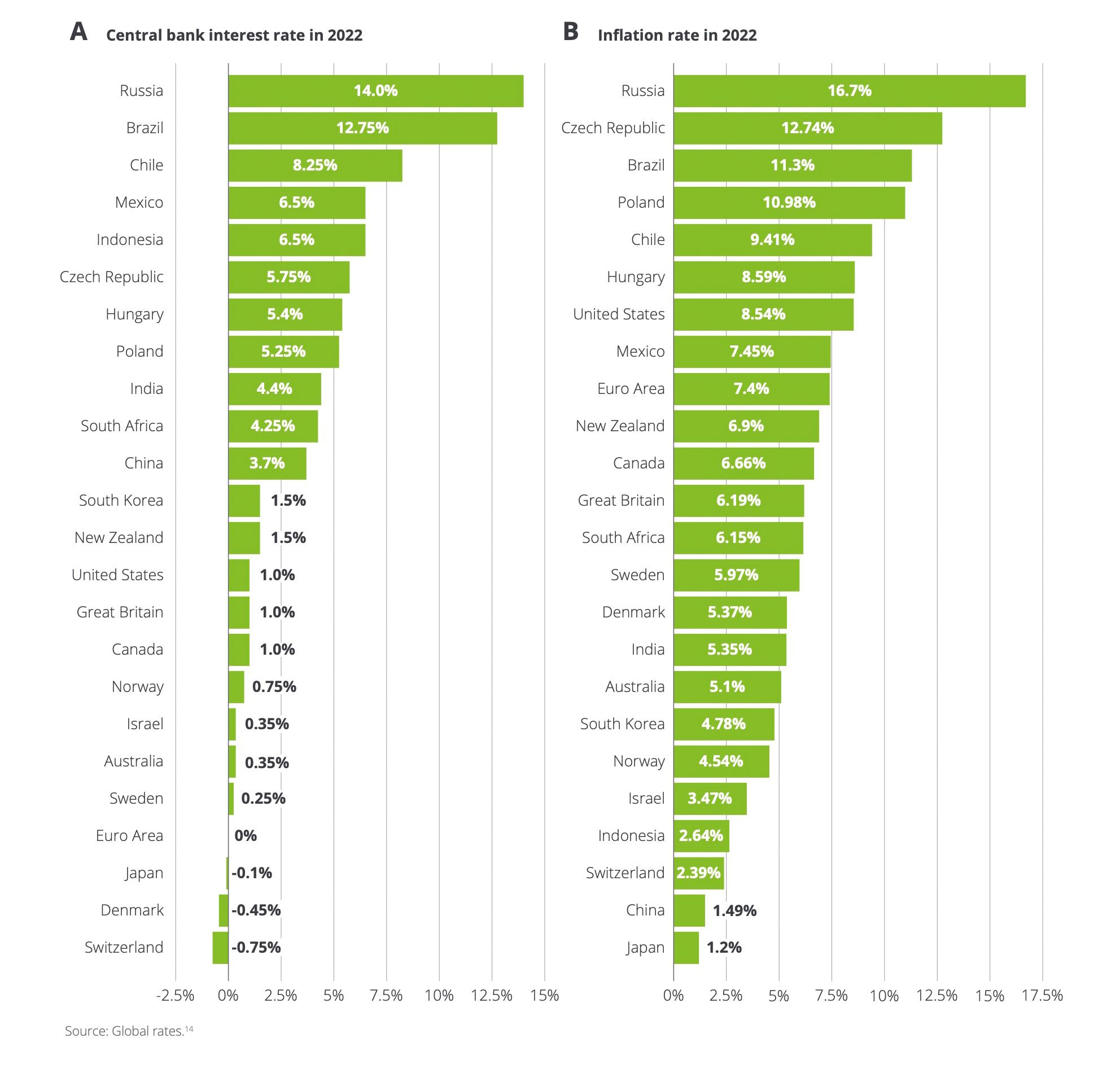

The Russian invasion of Ukraine changed everything

The war in Ukraine has added two new dimensions to energy transition efforts: resilience and sovereignty. Russia, with nearly 1/5 of the world’s proven gas reserves and the 6th largest proven oil reserves in the world, is the biggest supplier of oil and natural gas to Europe. European primary energy supply is highly dependent on these two energy sources (61% in 2021). In 2019, Europe imported 356 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas, 67% of which was via pipeline and 33% in the form of liquefied natural gas. Of the 237 bcm pipeline imports, more than 80% came from Russia. Although Russian gas imports fell to 155 bcm in 2021, Russia was still the biggest natural gas exporter to Europe, supplying 45% of European natural gas imports (LNG included). It is relatively easy to find alternative sources of supply for Russian coal and oil, since they do not suffer from the inflexibilities inherent to the bilateral trading of pipeline gas. As such, finding alternative natural gas supplies is more complicated in the short term. Substitution of pipeline gas with LNG is limited as a large share of the global LNG trade is under contract, leaving only a small portion for trade on short-term markets. Moreover, this leaves LNG regasification terminals, and the pipelines evacuating the gas from the terminals, at risk of rapid saturation.

Energy transition strategies need revision

The EU sectors most exposed to imports from Russia are either power generators or energy-intensive industries like chemicals and metals. Having identified these sectors and making them more resilient to the disruption of Russian oil and gas supplies, raises the question of how to faster replace these GHG-emitting energies with clean sources of energy. This substitution has already been planned in the long term, but efforts should be accelerated and advanced wherever possible. According to the IEA, short-term measures such as consumer-side efforts (sufficiency), accelerated renewables development, maximization of electricity generation from bioenergies and nuclear power, replacement of Russian supplies with alternative suppliers and accelerated energy-efficiency improvements can reduce European gas imports from Russia by 1/3 (50 bcm) within one year.

The new perspectives on resilience mentioned above require a reevaluation of strategic choices. Natural gas is considered a transition technology toward climate neutrality, especially for replacement of coal-fired power generation, for the conversion of steel production from blast furnace to direct reduction route, and also for some other industrial sectors. Some hydrogen strategies moreover consider reformer-based low-carbon hydrogen imports from Russia as a key technology for transitioning to climate neutrality. It should thus be assessed whether the gas demand of these sectors can be met in a secure way and whether price hikes in gas will have long-term effects on the use of the fuel. A faster transition towards renewables and other low-carbon technologies can thus help alleviate tightness in the gas market while bringing CO2 emissions down. Moreover, the steep rise in oil and gas prices incentivizes expansion of fossil fuel production capacities around the world, risking the creation of long-term stranded assets.

What can government and industry do?

There is a massive need for action from companies, policymakers, and civil society. Governments should make clear and binding commitments that the measures agreed upon in the Paris Climate Accords and the paths taken to implement and increase climate policy ambitions will continue to be pursued with great vigor, even under the new political framework conditions. Moreover:

Synergies should be leveraged by integrating climate policy and efforts to strengthen the resilience of energy systems and economies. These synergies can be achieved via electrification and ambitious measures to improve energy efficiency, via a circular economy for strategic materials, via targeted infrastructure adjustment, via fundamental changes in market design and finally, via accountable political support measures to accelerate learning curves and achieve technological improvements and massive cost reductions.

In the context of increased resilience it is not only the diversification of energy sources, away from fossil to climate-neutral energies, but also the diversification and restructuring of fossil energy supplies that will have to play an important role.

The integration of both climate and resilience policies into global ambitions furthermore requires significantly enhanced international cooperation.

Industry leaders are central players and enablers of the transition. On the one hand, their actions depend on political framework conditions and, on the other, the transition can be accelerated with proactive action by companies:

In the short term, many companies are facing the challenge of significantly restructuring their value chains due to sanction policies, changing economic conditions, and the vulnerabilities that have become clear in recent months and years.

A resilient investment plan involves a diversified portfolio, not only in fossil energy sources like oil, natural gas and coal, but in low-carbon energy technologies.

The necessary greening of value chain efforts should also be considered an integral part of appropriate analysis and restructuring processes for achieving major synergetic effects.

As a result of rising commodity and goods prices, some sectors of the economy are burdened with cost inflation, while others generate extraordinarily high profits. These additional profits should primarily and consistently be invested into transformative technologies and/or systems for generating benefits for growth, jobs, and social welfare.

Contact

Bernhard Lorentz

Managing Partner Deloitte Sustainability & Climate GmbH

Global Consulting Sustainability & Climate Strategy Leader