G7 economies

In an uncertain recovery

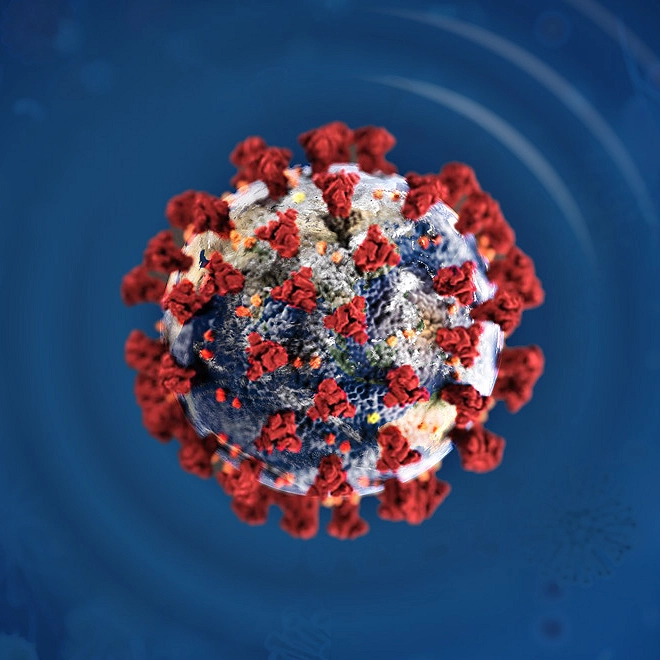

Economies in the G7 are witnessing a nascent recovery. But whether this recovery will be a swift one depends on the trajectory of COVID-19 in these countries.

IF the post–World War II era is something to go by, the COVID-19 pandemic will remain arguably the deepest scar for G71 economies for some time, in terms of the virus’ impact on both human health and economic activity. The pandemic has left in its wake a trail of anxiety, leaving people concerned about their health2 and businesses struggling to remain afloat given the sharp drop in demand. Within the G7, economic activity has been hit the most for the United Kingdom—its GDP fell by 20.4% in Q2 from Q1,3 the sharpest quarterly contraction since the series started in 1955.4 Yet the United Kingdom is not alone to suffer. Its G7 peers in Europe also experienced strong declines in GDP in Q2, and across the Atlantic, the United States’ economy fell by 9.1%. Predictably, governments and central banks have reacted fast to counter the downturn, enacting large stimulus measures to aid the most vulnerable and set recovery in motion.5 Yet stimulus is hardly a guarantee that any recovery will be swift. For much depends on the trajectory of the virus. And even when this is over, countries will have to deal with deteriorated fiscal balances and battered economies, not to mention the health and social scars of the pandemic itself.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The contraction due to the pandemic has been worse than the downturn in 2009

Economies have suffered as consumers cut spending after COVID-19 spread across countries. In the second quarter, consumers held back as they worried about contracting the virus and avoided "nonessential” expenditure due to deteriorating labor market concerns.

Spending by households or consumers fell sharply in Q2—ranging from 8.2% in Japan to 23.1% in the United Kingdom. Fear of being in proximity to other people and closure of certain establishments due to social distancing measures meant that spending on some goods and services suffered more than that on others.6 In the United States, for example, consumer spending on recreation fell by 49.5% in Q2; transportation (down 36.7%) and food services (down 34.2%) also saw sharp declines. A similar trend was evident in other countries.

Monthly data on retail sales and manufacturing activity shows that a recovery is likely underway in G7 economies, although it is too soon to conclude whether this is a sustained sharp upswing. While retail sales have picked up in recent months in most G7 economies, they remain subdued in some relative to pre–COVID-19 levels. In Japan, for example, sales in July were still 6.3% below February while in Italy, sales in June were 2.7% lower than in February. Manufacturing activity too is edging up after sharp declines mostly in March to May—for August, the Purchasing Managers’ Index data shows an expansion in every G7 country barring Japan and France.7 Yet manufacturing output in almost all economies is still below levels witnessed in December last year (figure 1).

Monthly data on retail sales and manufacturing activity shows that a recovery is likely underway in G7 economies, although it is too soon to conclude whether this is a sustained sharp upswing.

With COVID-19 continuing its spread,8 consumers still wary about their health and finances,9 and demand far from booming, G7 economies will likely continue to be under pressure. According to Deloitte economists, GDP in the United States is set to contract by 6.4% this year and by 1.7% in 2021.10 And forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reveal that the contraction in G7 economies in 2020 will likely be worse than in 2009 when the previous recession was underway (figure 2).11

Fiscal and monetary response to the crisis has been strong

Governments have responded to the crisis with a string of fiscal measures to address both the health and economic aspects of the pandemic.12 In the United States, for example, there have been three specific approaches—aid for individuals with an eye on health, education, and labor market conditions; help for businesses through instruments such as loans and guarantees; and efforts to counter the pandemic through health-related spending, such as on testing and vaccine development. Other countries have also moved on similar lines using multiple fiscal instruments, such as taxes, credit facilities, and transfers to businesses to shore up economies (figure 3). Figure 3 also shows multiple governments’ focus on aiding people who have lost jobs due to the pandemic as well as small businesses that tend to be left out of more sophisticated credit markets. In Japan, for example, a key focus of two emergency economic packages worth 40% of GDP is cash handouts to affected households, transfers to affected small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and local governments, and incentivizing credit lending. And in Europe, while countries have launched their own efforts, the European Union’s European Stability Mechanism provides funds worth about 540 billion euros to finance expenditure directly related to the pandemic in the region while the Next Generation package worth 750 billion euros focuses on a coordinated recovery effort.13

Governments have responded to the crisis with a string of fiscal measures.

It’s not just governments that have acted; monetary authorities, too, have tapped into their arsenal aggressively to stem the current economic downturn. While the fiscal response has taken center stage, especially to buffer the short-term economic impact of the pandemic, the role of the monetary authorities has largely been of a market stabilizer. Central banks have focused on easing financial stress by acting as an intermediary between fiscal authorities and financial markets while facilitating a smooth flow of credit to the private sector. In March and April, when concerns about household and corporate liquidity had hampered the functioning of key financial market segments, central banks were quick to respond by easing policy rates (figure 4). These were followed by more targeted operations, such as asset purchases (figure 5). In the United States, for example, the Federal Reserve reactivated the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF)—first established in late 2008—to support the issuance of asset-backed securities and embarked on large-scale purchases of government bonds. Asset purchases, in turn, have ensured smooth functioning of the market for US Treasuries, thereby preserving its key role in the pricing of financial assets.14 Such purchase programs are key to restore the financial market’s confidence and create the necessary credit conditions for a potential rebound of aggregate demand. Central banks have also focused on targeted lending operations. The Fed, for example, has launched several emergency lending programs worth a total of US$2.3 trillion aimed at businesses, states, and cities. And in Germany, the Bundesbank has made available additional funds to refinance short-term liquidity provisions through public development and commercial banks.

Monetary authorities too have tapped into their arsenal aggressively to stem the current economic downturn.

Interestingly, governments are increasingly assisting central banks to offer additional lending support. The United States Department of Treasury has provided a backstop to various lending programs by the Fed, while in the United Kingdom, the Bank of England’s (BOE) purchases of commercial paper enjoys complete guarantee by the UK Treasury.15

There are, however, challenges ahead

As Deloitte’s State of the Consumer Tracker reveals, consumers across G7 nations remain anxious about their health and job prospects due to the ongoing economic downturn.16 These concerns will continue to weigh on consumer spending in 2020. Businesses in certain sectors, including tourism and hospitality, aviation, and food services, will struggle more than others as consumers hold back on their spending and the flow of foreign tourists remains sharply and consistently lower than last year. Tourist arrivals have all but dried up and are nearly close to zero in almost all G7 countries. And although some countries in Europe have opened cross-border movement for select nationalities,17 tourists haven’t been returning to key destinations in the region. Available data for Spain, for example, shows that tourist arrivals were up in June from zero in the prior two months but are still 97.7% below the arrivals seen a year ago. According to the International Air Transport Association, passenger demand for aviation for the whole of 2020 could fall by as much as 52.6% in North America and by 56.4% in Europe.18 Given the sharp dent to demand, the risk of bankruptcies has risen, with small businesses being most vulnerable, especially if fiscal and monetary support is scaled down.19 Rising bankruptcies may, in turn, hit banking asset quality and strain credit growth.

The massive amounts of stimulus engaged by G7 governments mean that a return to fiscal prudence will be a challenge over the medium to long term. According to the IMF, general government fiscal balance as a share of GDP for advanced economies is set to deteriorate by 13.3 percentage points in 2020 compared to a year before.20 Within the G7, the IMF expects the rise in the deficit in 2019–2020 to be the highest in the United States (23.8% of GDP from 6.3%), followed by Canada (12.6% of GDP from 0.3%) and Germany (10.7% of GDP from a surplus of 1.5%). As borrowing surges to fund fiscal stimulus, government debt is also expected to rise sharply (figure 6). For countries such as Italy that had not long ago suffered during the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, the expected rise in government debt will be a worry. High debt and deficit will likely translate to future cuts in fiscal support and higher taxes, thereby putting more burden over the long term on the younger generation, which is worrying for countries with aging populations such as Japan, Germany, and Italy.21

The massive amounts of stimulus engaged by G7 governments mean that a return to fiscal prudence will be a challenge over the medium to long term.

Strong monetary stimulus has meant a sharp rise in central banks’ balance sheets, which were already at elevated levels after a surge since the global downturn of 2008–2009. Between February and July of this year, the total liabilities of the Fed went up by 67.7% and for the European Central Bank (ECB), they shot up by 45.7%. Also, key policy rates are at record lows with bond yields too dropping sharply as investors rush to safety (figure 6). Low interest rates, if they continue for long, are not good news for savers. Pensioners too suffer as they typically hold more of fixed-income assets in their portfolio than younger people who likely invest more in equities. If yields remain low, people—especially the younger generations—may end up working longer due to higher retirement age, pay more taxes, and yet earn lower incomes in their old age. Insurance companies and pension funds face the risk of falling short of their liabilities.22 Most importantly, low interest rates, along with high government debt and deficit, leave less room for monetary and fiscal policy responses should another crisis arise.

Low interest rates, along with high government debt and deficit, restrict room for monetary and fiscal policy responses should another crisis arise.

The biggest worry is the virus itself

The biggest challenge, however, is the virus itself. Data on new virus cases and deaths due to COVID-1923 shows that the pandemic is far from over. Even in countries where the spread of the virus has been under control for some time, localized outbreaks have happened—such as the United Kingdom, Spain, and Australia—resulting in local lockdowns, social distancing measures, and travel restrictions.24 Uncertainty, therefore, will continue till a credible vaccine is found, which seems unlikely at least till the end of this year.25 By that time, even if a vaccine were to be found, ensuring production and supply will depend on supply chains spread across the globe, competition with other countries for supplies, and the logistics of delivering these vaccines to the population.26 Till that time people and businesses in G7 countries, as in other parts of the world, will have to learn to live with the virus.

Deloitte Global Economist Network

The Deloitte Global Economist Network is a diverse group of economists that produce relevant, interesting and thought-provoking content for external and internal audiences. The Network’s industry and economics expertise allows us to bring sophisticated analysis to complex industry-based questions. Publications range from in-depth reports and thought leadership examining critical issues to executive briefs aimed at keeping Deloitte’s top management and partners abreast of topical issues.