The future of regulation: Navigating the intersection of regulation, innovation, and society has been saved

Perspectives

The future of regulation: Navigating the intersection of regulation, innovation, and society

Government & Public Services leadership perspectives

Explore Content

- The connected regulator

- Regulation, disruption and the future of work

- My algorithm doesn’t fit

- If at first you don't find a balanced regulatory model—try, try, again

- Keep calm and regulate: How disruptive technologies are disrupting regulators

Regulators challenged by same tech advances that could benefit them

From Compliance Week's interview with Mike Turley, Government & Public Services Global Leader

Innovation and disruption, however, while welcomed by many, is not without unique hazards, especially for regulators who increasingly find themselves at risk of falling hopelessly off pace or derelict with their responsibilities.

Technology is changing the world where we live and work with incredible speed.

Innovation and disruption, however, while welcomed by many, is not without unique hazards, especially for regulators who increasingly find themselves at risk of falling hopelessly off pace or derelict with their responsibilities.

That conundrum is the topic of a new Deloitte report on the future of regulation. “The Regulator’s New Toolkit: Technologies and Tactics for Tomorrow’s Regulator” focuses on how regulators can leverage new technologies and business tools to increase their efficiency and effectiveness while reducing business compliance costs in the process.

Regulators find themselves allocating increasing amounts of staff time and funding to understanding the business dynamics and regulatory implications of new markets and industries, the report says. At the same time, they face a host of traditional challenges: identifying “bad actors,” monitoring compliance, and speeding up regulatory processes to better serve and protect the public.

The good news, according to Deloitte: “While emerging technologies and new business models can pose challenges for regulators, they also present opportunities.”

Breaking out of silos

To adapt to evolving trends, regulators need to change their longstanding mindset, breaking out of traditional “silos.”

Mike Turley, Deloitte’s global public sector leader, recalls a recent conversation with his colleagues that illustrated the challenge. “One of them, from our automotive business, was saying that driverless cars and autonomous vehicles were all about the automotive sector,” he said. “Then, one of my colleagues in the tech sector said, ‘Well, actually, it’s all about technology; it’s all about data, platforms, and interoperability.’ I said, ‘It’s all about governments, because they will regulate all this.’ ”

The conversation, he said, parroted debates regulators are having and “highlighted the fact that there’s no systemic dialogue between different sectors and the regulators.”

Also consider Uber’s phenomenal growth, Turley suggested. In London alone, the service boasts 40,000 drivers; 65,000 serve New York City. “That is a hundred thousand drivers, in two cities, in a relatively short period of time,” he said. “These companies scale so fast. How do you regulate that?”

Uber, Turley said, also illustrates the jurisdictional blurring regulators face. Is it a technology platform that connects users with drivers? Is it a car-sharing platform? Is it a cab? Is it a restaurant business, because it delivers food?

“All of those are regulated in different ways,” he says.

Overworked and understaffed

A common problem faced by regulators throughout the world is that they lack needed resources.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, in an example cited by the report, had 526,579 patent applications pending at the end of 2017, potentially harming fledgling businesses by hampering their ability to attract funding and sell products. An internal study concluded that each year of delay in reviewing initial patent applications that ultimately receive approval reduces a company’s employment and sales growth by 21 percent and 28 percent, respectively, over five years.

“We did some work on the federal code of regulation in the U.S. The average time between updates was going on 20 years,” Turley says. “In a world that is changing rapidly, it is hard to see how you can have that ‘regulate and forget’ approach. You need to think about regulation more like we do with software. You have upgrades, and it becomes live and adaptable.”

Technology tools to the rescue

Among the tools becoming business mainstays that can also offer regulators new efficiencies are: artificial intelligence-based technologies, including machine learning, image recognition, speech recognition, natural language processing, and robotics.

The fundamental step in any effort to modernize regulation and reduce administrative burdens is a review of existing regulations, looking for those that are outdated, duplicative, or blocking innovation.

Deloitte’s Center for Government Insights used text mining and machine learning to parse through more than 217,000 sections of the 2017 U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. It found nearly 18,000 sections containing text that was extremely similar to passages in other sections. A regulator could similarly use text mining to analyze previous regulations for duplicative, overlapping, or unused rules that should be discarded.

AI can also augment regulators’ decision making by parsing through masses of forms and data.

Many regulatory agencies already use data analytics and AI to identify fraud, the report notes. The Securities and Exchange Commission uses machine learning to identify patterns in the text of public company filings. These patterns are compared to past examination outcomes to, for example, uncover red flags in investment manager filings.

SEC staff, according to Deloitte, says that these techniques are five times more effective than random selection at finding language that merits referral to enforcement.

Crowdsourcing is another modern phenomenon that may help regulators “tap into their constituents’ collective intelligence and use it to regulate more effectively,” the report says.

In the United Kingdom, for example, a Red Tape Challenge program asked citizens to suggest ways to simplify existing regulations.

Given the complexity —and frequent unpredictability —of new technology, companies and regulators alike are turning to “sandboxes,” controlled environments where innovators can test products and applications.

The report notes that the Canadian Securities Administrators maintains a sandbox that provides time-limited relaxation from certain regulatory requirements placed on startups. In the United Kingdom, the Financial Conduct Authority, in collaboration with 11 other financial regulators, has created a global FinTech sandbox.

“The use of sandboxes can actually help you understand what it is you’re going to regulate, rather than try and regulate before you understand it,” Turley says. “You need a way in which you can test this, understand the implications, and understand how people are going to use it; then you can regulate in a way that looks at outcomes rather than just inputs.”

Another tool, robotic process automation (RPA), can include software that mimics the steps humans would take to complete various tasks such as filling out forms, transferring data between spreadsheets, or accessing multiple databases.

Based on an analysis of the U.S. federal government workforce, Deloitte estimates that automating manual tasks through techniques such as RPA could free up millions—as many as 60 million hours a year in regulatory staff-hours.

Government entities have also started to use RPA to sift through large data backlogs and take appropriate action, leaving more difficult cases to human experts. The Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), for example, uses RPA in its application intake process.

When CDER automated a part of the drug application intake process, it was able to slash processing time for applications by 93 percent, eliminate 5,200 hours of manual labor, and save $500,000 annually, the report says.

As for “big data,” Deloitte concluded that “most regulatory data collection today is being done with little or no standards.”

“Regulators need to develop common standards to collect and store data to improve rulemaking and oversight,” the report says. Advanced text and data analytics can then “help regulatory agencies make sense out of massive amounts of data, predict trends, and identify potential risks in ways that were not previously practical through manual analysis.”

These new and emerging tools, the report adds, can also be particularly useful in helping regulatory agencies find redundant, outdated, and overlapping regulations.

“They can also be used to analyze data about their interactions with businesses, drawing on internal and external sources such as survey data, call center and issue-tracking systems, help desk complaints, social media scans, and Web scans,” it says.

Blockchain—the distributed, encrypted digital transaction ledger at the core of Bitcoin—could be useful for agencies dealing with high volumes of sensitive records. For example, a central bank could deploy it for interbank settlements or cross-border transactions.

“In the new world, most data is outside the organization, rather than inside,” Turley says of data collection, offering an example of how strategies are evolving. “If you want to look at food hygiene regulation, the best information you can get might be off social media, including Facebook posts or Twitter tweets from people who’ve got food poisoning. You use that to supplement your internal processes … That’s part of how to use big data to do regulation better.”

“Another piece is how you shift to self-regulation in some cases,” Turley added. “How do you use the algorithms that have been developed for many processes to give you a better risk-based approach to how you apply the regulation? How do you then develop your inspection regimes in a way that moves from what some organizations have called ‘officer intuition’ to intelligence-based inspections?”

All well and good, perhaps, but can you trust these alternative sources of data?

“That’s why you have to use some of the artificial intelligence processes to weed out patterns,” Turley says. “You need to build a picture based on a richer set of data, rather than just skewing it entirely to one set of potentially rogue reports. You build from multiple sources and then use machine learning [to determine patterns], rather than having humans poring over it.”

Navigating public comments

As part of their rulemaking processes, and the Administrative Procedures Act, government agencies must allow the public to comment on proposed regulations. That important process is another pain point for regulators.

“Each year, millions of people comment on pending rules and regulations, and agencies must find what is relevant in such comments,” the report says. “But as technology is advancing, individuals and organizations are increasingly using bots to post ‘fake’ comments to amplify their positions.”

It is estimated that “bots” were responsible for more than a million of the 22 million comments the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) received on its call to consider repealing Obama-era net neutrality protections.

The FCC, Deloitte says, is using analytics and AI to identify and combat such activity. The agency contracted with FiscalNote, a government relationship management company, to analyze all 22 million net neutrality comments, using natural language processing techniques to cluster them into groups and identify similarities in structure and word usage. The analysts discovered hundreds of thousands of comments with identical sentence and paragraph structure.

Analytics and AI can also be used to assess the relevance and sophistication of each comment.

“This calculation may draw on a number of factors, including comment length; the number of attachments submitted with the comment; and the complexity (or coarseness) of the language,” the report notes. The FCC is also developing a tool that would score each comment it receives for its “probable substantive value,” in other words, how likely it is that the agency should consider the comment.

“Regulators are well-positioned to build such tools, because they often have historical information to validate the variables used to flag comments worth further consideration,” the report says. “Agencies will have records from past rulemaking processes in which certain comments were tagged as warranting a substantive response. These records can be used to build supervised machine-learning algorithms.”

Reaching out to disruptors

A key challenge for regulators is how to create and foster a more constructive dialogue with business disruptors.

“Startups that disrupt established industries, whether taxicabs, hotels, or banking, often enter markets with entirely new business models—and typically without asking for permission from government,” the report says. “The lack of dialogue between innovators and regulators often causes friction and can lead to restrictions or outright prohibitions that may not be in the public interest.”

“I would like to see more of a more constructive dialogue between disruptors and regulators,” Turley says. “Some of the early disruptors sort of said, ‘Come after us if you can,’ which is not a particularly helpful way of looking at things.”

“That continuing and evolving process will be one that separates the most successful disruptors and the most successful regulators,” he says.

The connected regulator

By Mike Turley, Government & Public Services Global Leader

Driving into work recently, I was alarmed to see my all digital dashboard crash to automotive equivalent of the Blue Screen of Death, nothing to show what speed, warnings or other indicators I am used to relying on to drive safely. This got me thinking that whilst the UK like many countries has an annual vehicle roadworthiness test, this doesn’t cover one of the most critical components—the software. This gap between the legacy regulatory framework and the new fast changing world is becoming a common theme in the lives of citizens.

Rapid, technology-led change can prove a challenge for those charged with regulating new disruptive forces in society. In recent years we have seen that the traditional reactive approach to regulation is simply too slow to respond to the pace of change that marks our economies today in areas as diverse as ride-sharing, home-sharing, crowdfunding, problematic algorithms, and data privacy.

These are not anomalies. Innovators, entrepreneurs, and established businesses are fully immersed in digital technologies and while their ideas may range widely, they will all use technology to disrupt the existing order. Often not recognizing the externalities or unintended consequences of their new business models, whether this be the increase in urban delivery traffic, congestion from ridesharing cars, or parties in Airbnb rentals.

What this means for regulators is that their approach needs to evolve in order to contend with the new characteristics being brought into play by these entrepreneurs and their ideas.

Speed. Being digital means being fast. The time it takes to develop a product and roll it out is growing shorter. What’s more, as more and more companies enter various marketplaces with disruptive technologies, the pace of acceptance from the consuming public is accelerating, too. Internet use in its first decade of public accessible use grew from 16M users in 1995 to 1.018B users ten years later. Skip ahead a little more to Facebook, which has an incredible 2.2B users today. And this before the company even turns ten!

Scale. All this to say that where regulators once had decades to understand and deal with a new technology, they now have months, not years.

This is because these new technologies get big, fast. In the past, regulators may have had the luxury to study other jurisdictions to guide them as they decided what was best for their own constituencies. A system based on precedents, each of them considered for their own merits, was possible. Today, technology means that a new product or service can cover the world in a matter of months. There is no time to study other jurisdictions and no time to use precedent to shape policy.

Complexity. As regulators attempt to keep up with these disruptive technologies, they often find that more than one agency needs to have input on how best to regulate the new product or service. With Airbnb, for example, those in charge of housing or rental policy may need to connect with those managing tourism. In Toronto, Alphabet’s Sidewalk Lab, a ‘smart city’ experiment that will develop some twelve acres of former industrial land, is peaking the interests of a plethora of regulators, from transit, sanitation, and housing authorities on the municipal level, to those concerned with privacy at the provincial level. The result is a whole ecosystem of regulators, all of which will have a stake in the new technology.

Regulating via ecosystems

Because of the speed, scale, and complexity that often accompany disruptive technologies, regulators will have to adopt new approaches to doing their jobs. Projects like Sidewalk Lab, where many responsibilities are shared, mean that regulators need to connect, network, and work together to ensure that they keep pace with changes in their jurisdictions. It is not unlike a complex surgery that involves dozens of medical professionals, each with their particular specialty. And often, as in medicine, one agency will take the lead, consulting as needed with others. Knowing regulators’ concerns ahead of time serve as important guides to the disruptors, helping them shape their strategy before roll out.

And lest we forget about the citizens who use technology to make sure their concerns are heard by regulators. Engaged and connected individuals are able to alert regulators to issues as they unfold, allowing regulators to anticipate policies. They too, play a key role in this regulatory ecosystem that aims to create more dynamic frameworks to deal with today’s disruptive technologies.

Oh and by the way, when I turned the car off and on it started up just fine.

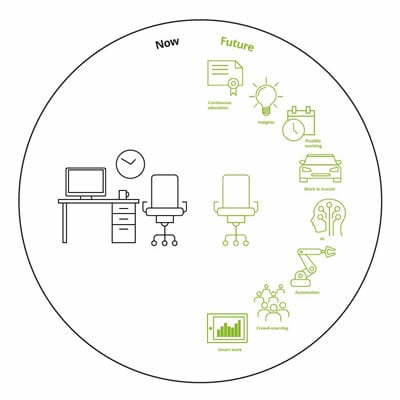

Regulation, disruption and the future of work

By David Barnes, Global Managing Director, Public Policy

Today’s disruptions are creating a slew of new products, services and ideas to enjoy. Transit, hospitality, financial services, supply chain management and so on are all innovating and challenging the status quo, reimagining how we go about our daily lives, how we interact and connect with each other, and how we should set rules that are in the public’s best interest.

Indeed, setting rules that are fit for purpose is key to unlocking technology’s and new business models’ full potential. What may have worked in the past is being upended, in this fast-paced, constantly shifting environment. But it is not just the digital platform revolution where the future of regulation applies. It also applies to other areas of import, like employment. Consider the changing contours of work and the workplace.

Work and skills are changing

Some companies today require a different kind of employee than was needed a generation, or even a decade, ago. Many of the hard skills to do a job well will be obsolete in just a few years. Labor market reforms to rewire skills will be required if economies are to effectively empower talent. APEC, OECD, G20 and other pivotal inter-governmental bodies are all actively debating the best way forward.

This new landscape, managed properly, may offer more opportunities than ever with a workforce equipped to handle the rapidly changing environment that will characterize economies for decades to come.

One of these opportunities for employers is worker mobility—that is, the ability to source the best talent wherever they are and whenever they need them. Regulators can help facilitate with tax incentives, state-of-the-art telecommunications infrastructure, and unemployment benefits that recognize the likelihood of periods of joblessness over the course of a person’s career. Businesses, too, have a role to play by considering how best to invest in lifelong learning and training, and redeploy talent to future-proof skills.

Laying the foundation and building on it

It is essential to understand the nature of these changes as they are happening. If, for example, people in the fields of education and training could predict the greatest skill deficits, they may be better prepared to move quickly and develop programs that teach these specific, in-demand skills.

Cooperating with the private sector, skills training programs can supplement or complement ongoing upgrades offered to employees in much the same way advanced degrees are becoming more and more customizable. By showing flexibility, a jurisdiction that grasps what employers will be looking for in the future will have a strong competitive advantage when it comes to attracting new investment.

We must also recognize that soft skills, such as adaptability and leadership, are more important than ever in an Industry 4.0 workplace where many workers, particularly millennials and Gen Z, identify as essential for their success.

The right skills: taking the cue from industry

Gaining this kind of foresight on in-demand skills requires open and transparent public-private dialogue. Only through such dialogue, can we foster smart rulemaking and holistically frame the issues and solutions.

Regulators, employers, educators, and all interested parties must listen to one another and share in the building of an employment eco-system in which:

- Companies can find the skills they need;

- Employees can find the jobs they want, and;

- Governments can better understand where policies are working and where there are gaps.

We’ve been here before

The good news is that change is not new. When the industrial economy of developed nations demanded better educated workers in the early 20th century, investments in the public-school system provided them. Similar investments in STEM disciplines at the post-secondary level have helped propel us into Industry 4.0. Both disruptions signaled the beginning of an exciting new era that presented a whole new assortment of opportunities. There’s no reason why we can’t do the same this time.

My algorithm doesn’t fit

When technology fails to consider the human factor, regulators must protect citizens and preserve society’s values

By Mike Turley, Government & Public Services Global Leader

When you stand over two meters tall you get used to things not fitting. Off-the-peg clothes, not typically. Desks in the office, rarely. And airline seats? Almost never.

Lately though it’s not just the physical things that don’t fit. Apparently because I don’t borrow money and I pay off my cards every month, my credit score is lower than the average university student. Vehicle insurance premiums vary depending on how much time I spend at work and from which email address I apply from. And if I buy two single airfares it can be cheaper than buying a return ticket…and the list goes on.

While these may be interpreted as annoying and trivial problems that we can learn to overcome by gaming the system, in practice they are evidence that algorithms are everywhere. That’s because massive amounts of data about people and their habits are now collected and analyzed, resulting in algorithms becoming a part of almost every interaction we humans have with technology. In fact, you reading this article right now is probably the result of an algorithm.

Algorithms are everywhere

Google owes their dominance of search engines to its unique algorithm. Facebook uses them to decide what news is fed to your page. Algorithms tell companies who should see their online advertising, let politicians know which voters are undecided, and guide judges when sentencing criminals.

Data fuels algorithms and it’s assumed that more data can lead to more accurate algorithms. But more data can also involve probing and influencing people’s lives in ways that raise privacy and human rights concerns. In other words, an issue for regulators.

Do algorithms reflect the values in society or those of their creator?

Organizations who use algorithms see it simply as a more efficient way to bring products and services closer to their target markets. However, as with the trends of people buying vinyl records or paper books, the way humans interact with algorithms isn’t always simple or predictable.

This is a critical consideration often overlooked during conversations about the impact of algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), and disruptive technologies—that is, how does human behavior disrupt the technology? Consider how studies have shown that algorithms used in US criminal cases can be racially biased. Or how algorithms were most likely used to target specific voters with specific “news” in the 2016 US election, with Russian interference now being investigated as the source of that news.

How do we fit such considerations into new regulatory models and ensure that there is transparency, fairness and equality in the way that algorithms, robotics, AI, and machine learning deliver services in a diverse society? Should there be a difference in service if I use my corporate email identity over my Hotmail account? What if I don’t have a corporate email?

What this means for the Regulator

Most people assume that data use, like justice, is meant to be blind and objective. But some regulators are already thinking beyond this assumption. Article 22 in the EU’s GDPR states that individuals have “the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her.” In other words, if someone doesn’t like what the machine says, they can appeal and get a second opinion, this time from a human.

With that in mind, it may be fairly asked if regulators will have to start examining how algorithms are designed. How transparent are they when it comes to things like breaches? How accurate? How accessible? How biased? Do they seek to remove inequality? Or do they reinforce it?

As more and more organizations rely on data gathering and algorithms to help them make decisions, more inequality and bias is likely to be exposed, some with serious consequences for people as they interact with financial services, health care, government, employers, or even the justice system. While I may find it amusing when Netflix incorrectly suggests a film based on my spouse’s likes that I would find painful to sit through—it can often be no laughing matter when an algorithm fails to read the nuances of human behaviour.

To reiterate a key theme from my previous posts, regulators and technology companies must work together to help address these problems. The new GDPR framework is an excellent example of a debate around the use of data that needs to be extended to the use of algorithms. We need to be in front of this issue through honest dialogue between businesses, citizens, and regulators alike. Because, as Alibaba founder and Executive Chairman Jack Ma noted at Davos, “The computer will always be smarter than you are; they never forget, they never get angry. But computers can never be as wise.”

If at first you don't find a balanced regulatory model - try, try, again

By Mike Turley, Government & Public Services Global Leader

Much of the history of regulation is one of reaction rather than pro-action. An example: In the early days of the automobile, a spate of pedestrian deaths prompted a campaign that eventually led to the first rules against jay-walking, ensuring that between intersections at least, the roads belonged first and foremost to cars.

Other examples abound. From health care to banking, from the military to education, regulations are almost always the product of something gone wrong (or the anticipation thereof) and the government’s response to it.

As a model for bringing in regulations to help keep people and their assets safe, this one has been largely effective. However, in the future, regulators may no longer be able to rely on this reactive approach, especially as faster, more scalable technologies are leading to more aero-dynamic business eco-systems, making it more difficult for regulators to keep up.

Playing catch up

Regulators are often faced with the challenge of having to catch up to new disruptive businesses. Uber and AirBnB are prominent examples. In their relatively short lives, they have had major impacts on the transit and hospitality industries in cities around the world. The speed of their entry into these markets has been a challenge for regulators who have already established frameworks with more traditional providers of transit (i.e., taxis) and hospitality (i.e., hotels).

Regulators have scrambled to respond—and sometimes that response has been severe. In Copenhagen regulators mandated that taxis should have seat sensors, video surveillance, and taxi meters, all regular features of traditional taxis but less common in the cars belonging to Uber drivers. Uber responded by pulling out of the market. While Danish taxi drivers are pleased, Uber drivers and their customers miss out.

A more nuanced approach

A more effective regulatory model may be found when the innovators and regulators find a balance. For example, in Portugal an innovative compromise was struck when Uber agreed to use the shared mobility platform of the city in return for cooperation on licensing. Perhaps coincidentally (or perhaps not) Uber recently announced that Lisbon would be the site of its Center for Excellence in Europe, creating jobs and revenue for the city.

Blunt instruments may not be necessary if different stakeholders—tax authorities, zoning boards, by-law enforcement—work together to envision and respond to disruptive change when it comes. In fact, some agencies are already taking a pro-active approach by issuing statements that anticipate where new technologies may run up against existing regulations. This will help guide entrepreneurs as they contemplate entering a marketplace.

You can’t predict the future, but best to be ready for it

Anticipating all the variables of a disruptive technology is about as easy as predicting the future. That is to say, not very easy at all. However, regulators can help ease the process by thinking more dynamically and maintaining open and frank dialogue with entrepreneurial tech companies.

The features that gave these disruptive technologies such massive impact—speed and scalability—will be the features of new technologies for years to come, especially as the intersection of artificial intelligence, advanced analytics, and human behavior becomes more prominent in our day-to-day lives. It is vital that regulators and entrepreneurs open up the channels of communication now so that both sides are ready for the future and whatever it brings.

I invite you to explore more future technologies that will impact the regulatory balance.

Keep calm and regulate: How disruptive technologies are disrupting regulators

By Mike Turley, Government & Public Services Global Leader

Driverless automobiles—we’re all excited for their arrival and the day when a long drive means catching up on work or taking a nap. Not surprisingly, auto makers and technology companies are excited, too, and are well down the path to presenting a viable driverless vehicle.

But before you start making a list of television series to binge watch in your car, know this: the excitement is very likely premature—not because of the technology, but because regulators are still trying to fully understand the implications of driverless cars and struggling to define new ways to address these innovations.

This is a problem—not just for driverless vehicles, but for all business models that depend on the cooperation of regulators. Virtually everything—from artificial intelligence and 3D printing, to sharing economy services such as AirBnB and Uber, and even to applications we’ve yet to imagine will need to bridge this gap.

Too fast, too soon

The disconnect between regulators and tech innovators is the result of a few things. One is speed. From development to implementation, technology helps products grow and hit markets at incredible speeds, often too fast for regulations to keep up.

Another is a lack of constructive dialogue between the two parties. Innovators tend to talk to other innovators, which is great for innovation. It’s not so great, though, when those products have to interact with people and societies—the very same people governments and regulators are tasked with protecting.

Driverless cars might be the perfect illustration of the regulatory disconnect. On the one hand, these vehicles will have four wheels and engines and in that sense, existing rules for automobile regulation—from emissions and safety to traffic laws—still apply. What creates challenges for regulators is what’s different about driverless cars.

For example: before they are ready for the road, traditional cars must be thoroughly tested. Do the brakes, steering, lights, etc. work properly? But with driverless vehicles, software will do the braking and steering and lighting. As yet, there is no testing for this outside the technology company itself.

Driverless vehicles will also have to satisfy regulators when it comes to interacting with cars driven by human beings. In some countries, a stop sign is merely a suggestion: drivers slow down but usually drive straight through. Will the software be able adjust to these different driving cultures? Complications like these explain why a manager from one large North American city recently told me that, while manufacturers see driverless cars on the road in five years, he can’t see regulations being in place for at least ten or more.

Get talking

Early dialogue addressing the concerns of regulators before problems arise will be critical to the future of regulation. In some ways, none of this is new. Regulators have been dealing with disruptive technologies for decades. What is new is the sheer speed and scalability. Today’s companies grow at extraordinary speed while regulators work at the same pace as always.

So the question is: how do regulators and innovators work together to close the gap? Over the next few months in this space, we’ll examine this issue more closely and look at a few solutions. We’ll explore some existing models and how regulators might adapt them for a future marked by disruption. We’ll show how regulators are becoming more networked. We’ll delve into the ongoing problem of human nature interacting with technology. And finally, we’ll look at how some jurisdictions are using regulations as a competitive advantage.

The thrill of new technology is undeniable – the world shares a common interest in seeing how these innovations will interact with and benefit communities across the globe. As technology drives forward, it’s critical to pause and consider the enormous responsibility government has in ensuring the safety and inclusivity of its citizens. Elon Musk’s outspoken position on AI highlights the need for regulators to stay focused on the long game—because while the role of the innovators is to disrupt, the role of the regulator is to find the balance between innovation and social responsibility.

I invite you to learn more about Deloitte's thoughts and insights on the Future of Regulation.