Get ready—federal borrowing is about to make corporate debt more expensive Economics Spotlight, December 2018

4 minute read

15 December 2018

Patricia Buckley

Patricia Buckley

The debt the Treasury needs to issue is expected to rise in the coming years, pressuring Treasury and other debt rates. If US Treasuries demand should soften, the rise in Treasury and corporate rates could be steeper than anticipated.

With the cuts to personal and corporate tax included in 2018 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and increases in government spending from the Budget Act of 2018, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) raised its deficit and debt estimates earlier this year. According to the CBO, “Federal debt is projected to be on a steadily rising trajectory throughout the coming decade. Debt held by the public, which has doubled in the past 10 years as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), approaches 100 percent of GDP by 2028 in CBO’s projections.”1 The CBO further noted that, over its 10-year time horizon, this increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio will put upward pressure on both short- and long-term interest rates. That’s in addition to the impact of the Federal Reserve continuing on its path of raising the federal funds rate.2

Learn more

Read the most recent US Economic Forecast

Explore the Economics Spotlight collection

Subscribe to receive more economics content

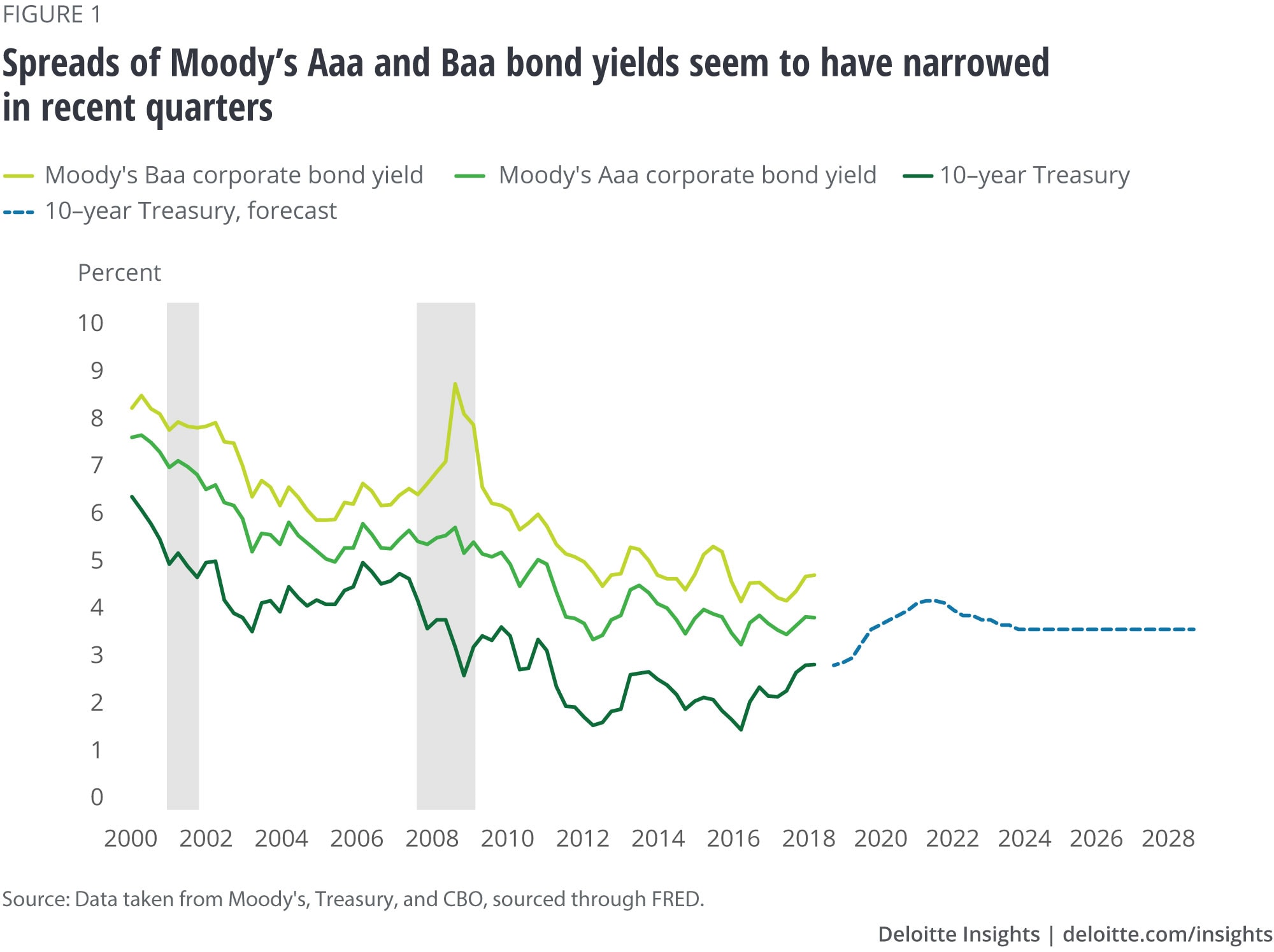

Rising rates on treasuries will, in turn, pressure corporate bond yields. Both Moody’s Aaa and Baa bond yields closely track 10-year Treasury yields over the long run (see figure 1). Post-recession (starting in mid-2009), the spread between Aaa corporate bonds has averaged 1.7 percentage points, while the spread between Baa corporate bonds has averaged 2.7 percentage points. It does appear, however, that the spreads have narrowed somewhat in recent quarters.

The CBO projects the interest rate on 10-year Treasury notes to increase to 4.3 percent by the middle of 2021 before falling to an average rate of 3.7 percent between 2024 and 2028.3 If corporate spreads remain at the post-recession average, yields on Aaa bonds could rise to around 6.0 percent by 2021 and to 7.0 percent on Baa bonds. This is higher than previously seen during this expansion. Even if the spreads remained at the lower levels experienced in the first three quarters of this year—1.0 percentage point and 1.8 percentage points for Aaa and Baa, respectively—Aaa corporate yields would rise to 5.3 percent for Aaa bonds and Baa yields to 6.1 percent. That’s substantially above the current rates of under 4 percent and just below 5 percent.

But the impact could be more severe if investors lose interest … just when we need investors more than ever

The rising debt-to-GDP ratio increases risks to the economy. According to the CBO, one of those risks comes from the fact that federal borrowing reduces national savings, leading to less investment, and lower productivity and wages. Perhaps more importantly, the high debt level also increases the risk of a fiscal crisis. One specific avenue by which a fiscal crisis could occur would be if investors lose their appetite for US Treasuries. As the CBO notes, this would make it impossible for the federal government to sell the securities necessary to finance operations “unless they [investors] were compensated with very high interest rates. If that occurred, interest rates on federal debt would rise suddenly and sharply relative to rates of return on other assets.”4 There is some evidence that at least one group of investors—foreign investors—are indeed losing interest.

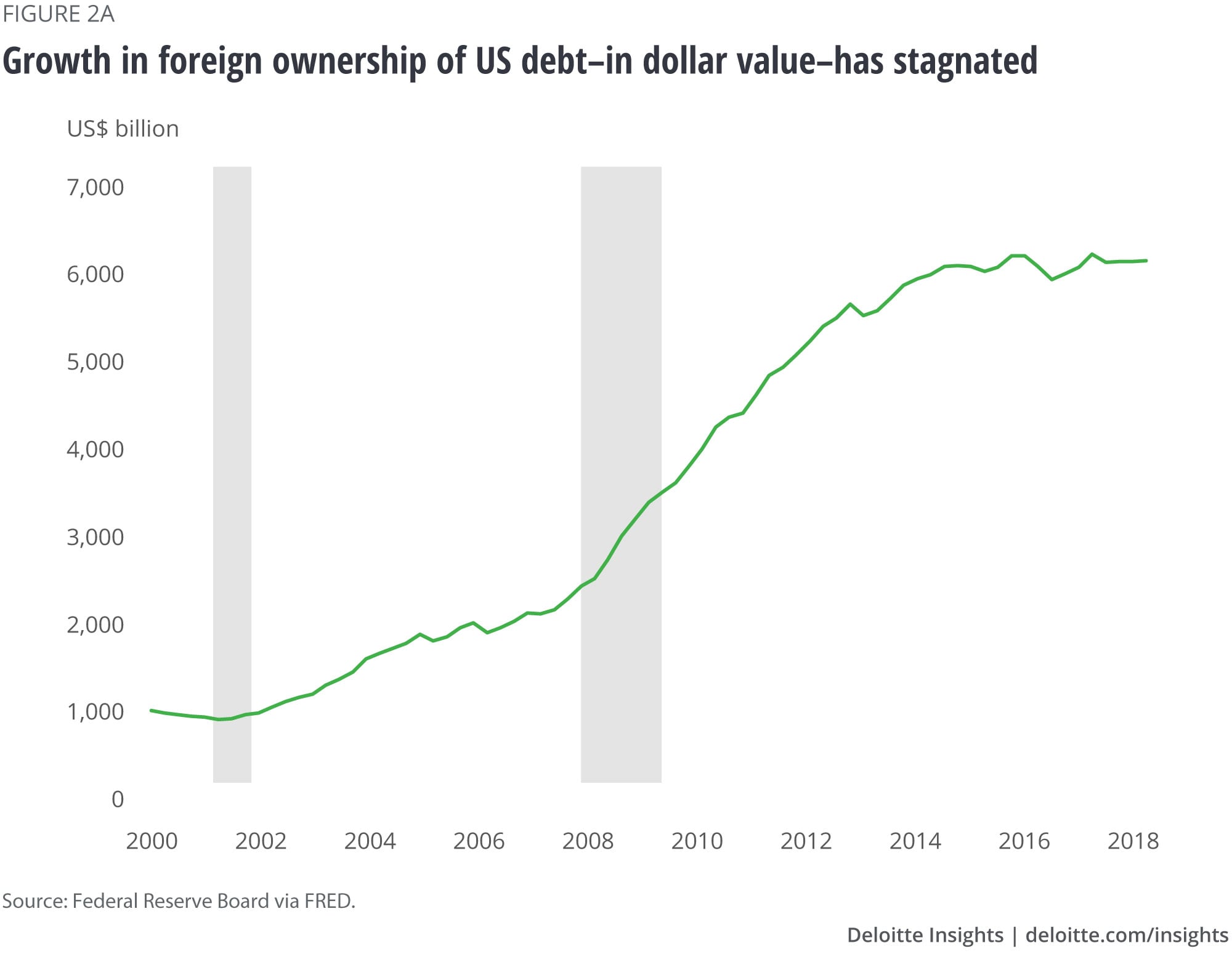

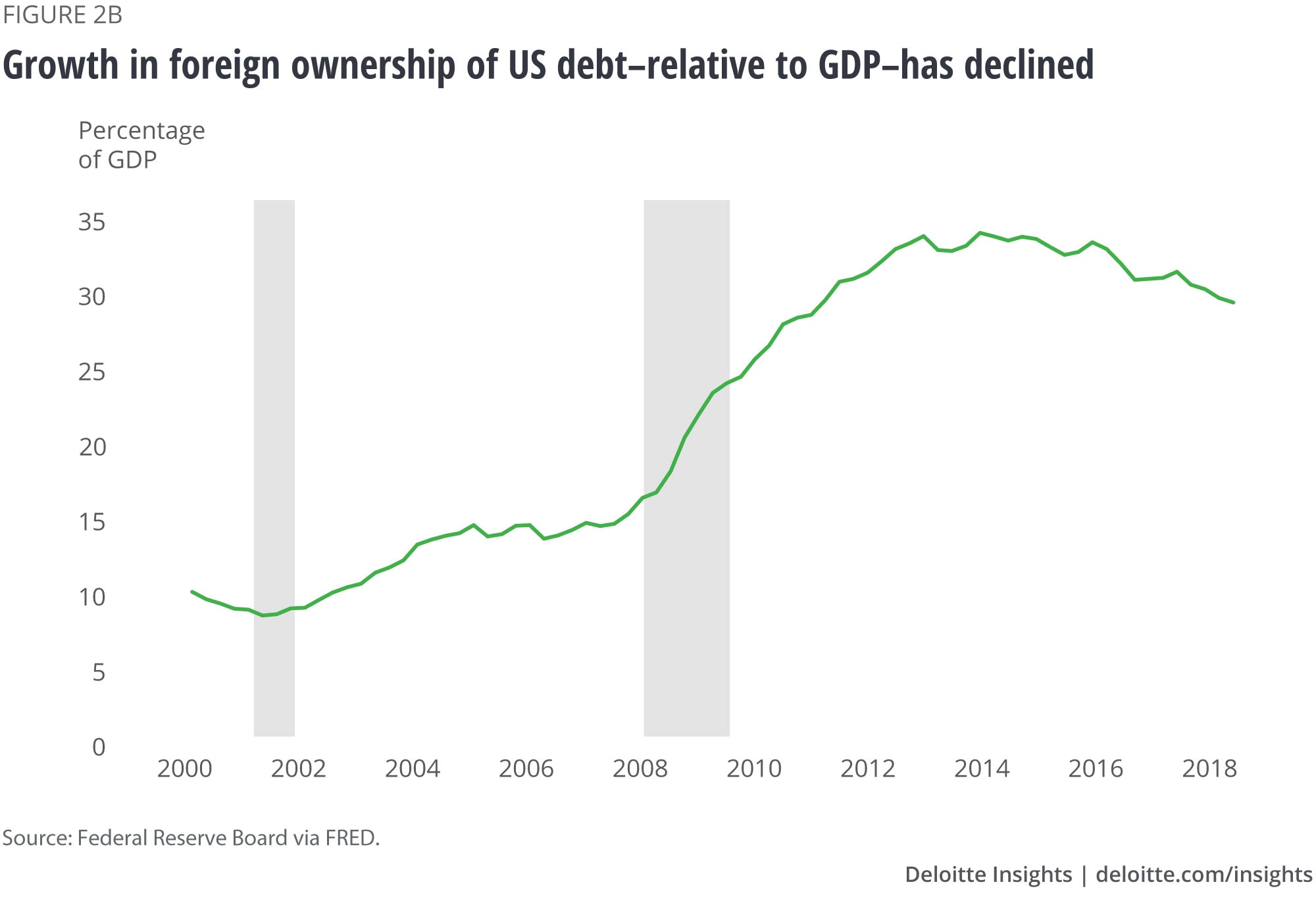

According to the most recent estimates from March 2018, foreign investors held 48 percent of debt held by the public, down from a high of 59 percent in June 2014.5 Figures 2a and 2b show growth in the foreign ownership of US debt has stalled in terms of growth in dollar value (figure 2a) and has experienced a decline relative to GDP (figure 2b). These declines are remarkable given how fast both were rising prior to 2014.

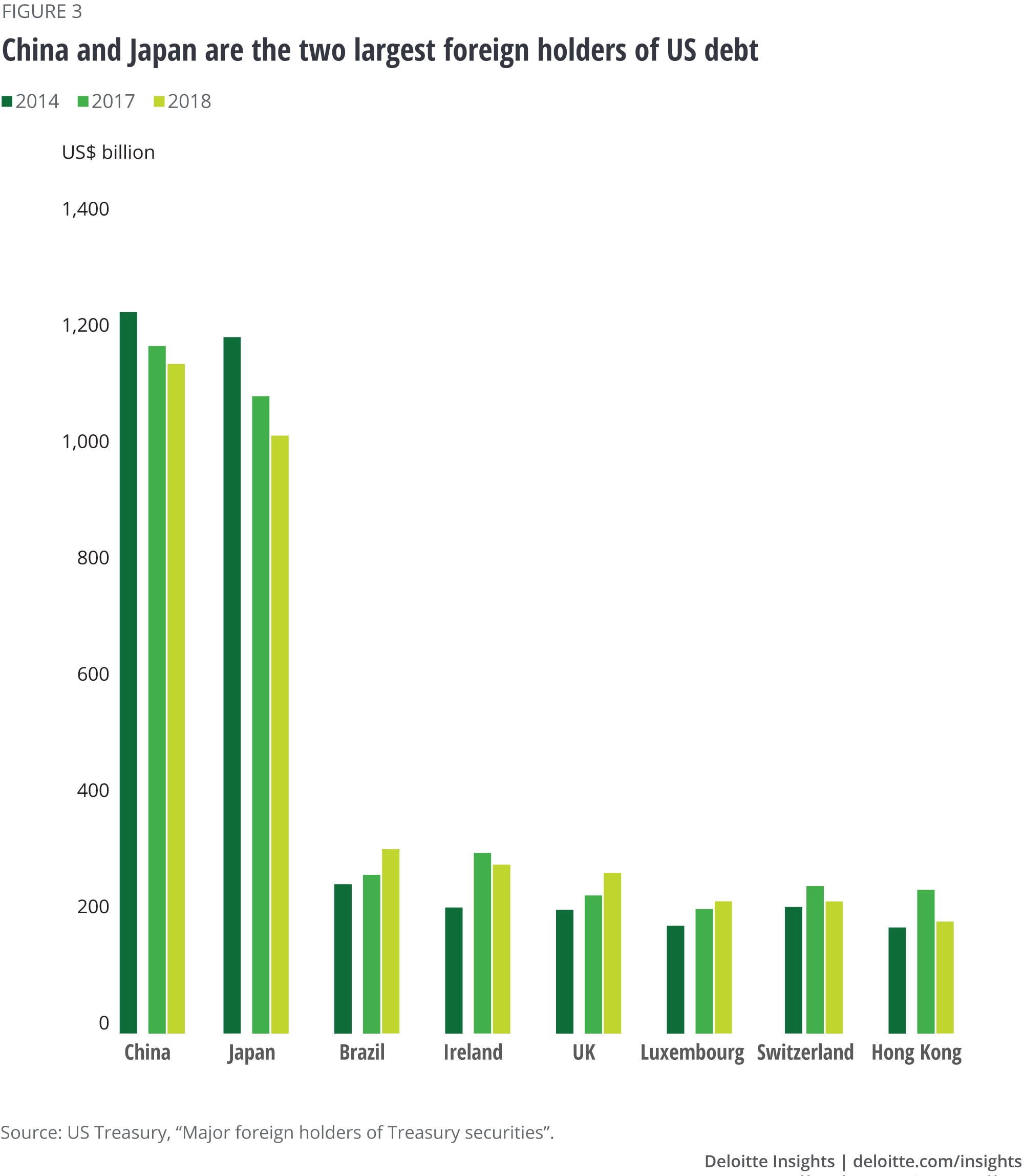

While not all foreign holders of US debt have reduced their holdings, the reductions are most pronounced with the two largest debt holders, China and Japan (figure 3).

With the waning of foreign appetite for holding US debt, the question becomes this: Will domestic purchasers be willing and able to make up the difference? And, if so, at what price? Will the CBO’s projected Treasury yields be sufficient to match the amount of Treasuries the government needs to finance US government operations with willing buyers or will rates be forced higher, not only for Treasuries, but also for private bond issuances? The age of cheap money is ended. However, what remains unclear is how much more expensive borrowing will become.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.