Voice of Asia Playing to win: Will political tensions derail economic gains in Asia Pacific?

21 minute read

08 March 2019

Although markets in the Asia Pacific region lost ground recently, they did so from a position of strength. Much the same could be said of the Asia Pacific economies. Having performed well through 2017 and 2018, they have only slowed a little, and they have the potential to remain resilient through 2019.

Will politicians damage economic prosperity in the Asia Pacific region this year? They certainly could.

Trade tensions present a clear and current danger, accelerating a slowdown that is already underway both globally and across the region. It is a key reason why financial markets have sent up some distress flares in recent months.

Yet Deloitte believes it would be a mistake to overstate the dangers.

Although markets in our region lost ground in recent months, they did so from a position of strength. Much the same could be said of the Asia Pacific economies. Having performed well through 2017 and 2018, they have only slowed a little of late, and they have the potential to remain resilient through 2019 as well.

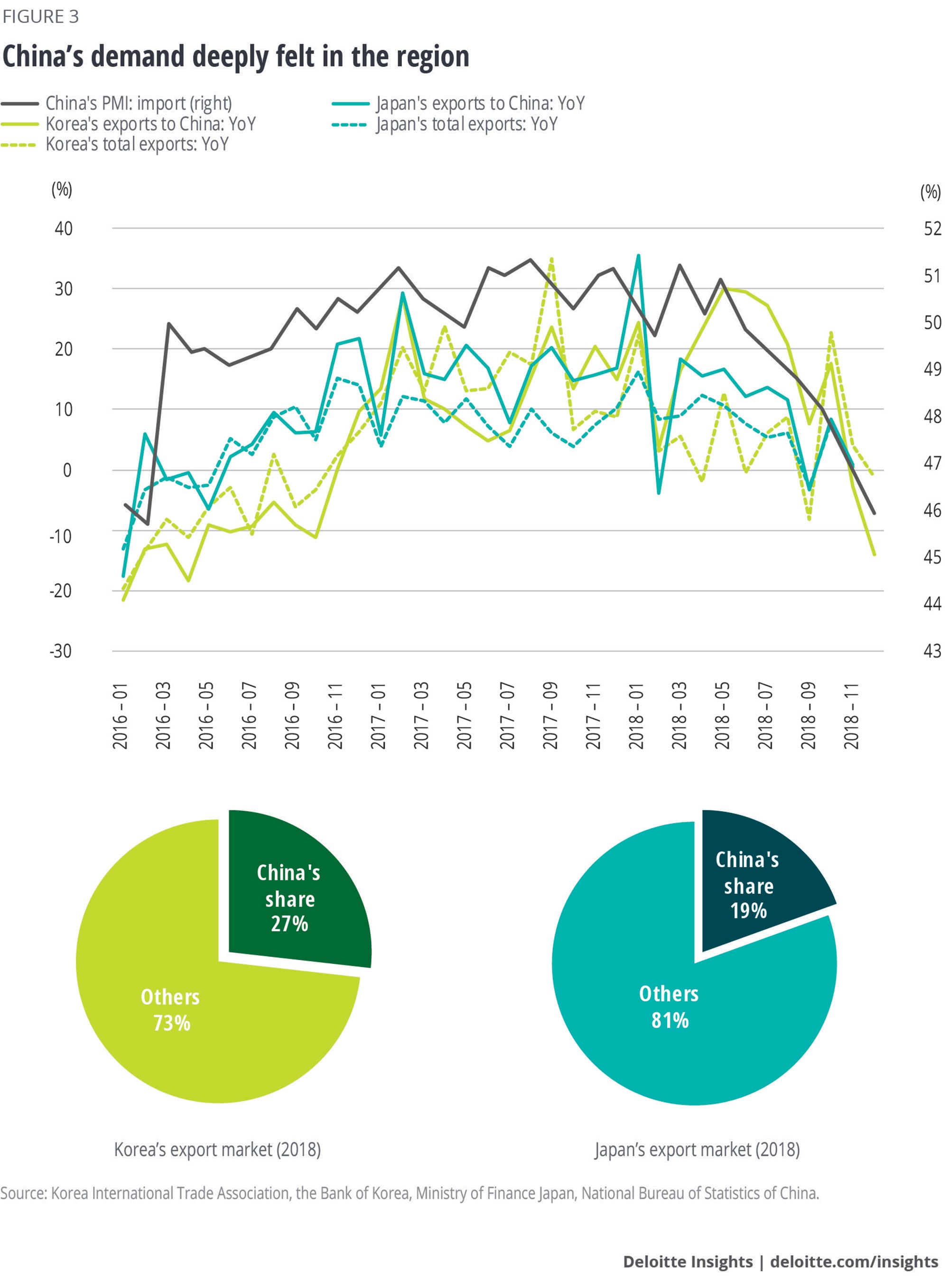

The economies of Asia Pacific are enormously dependent on trade, so there is potential for Tokyo and Beijing to take the political lead in fostering trade integration in general, and in smoothing current global trade tensions in particular.

There remains a distinct possibility that Beijing and Washington could step back from posturing and focus on the potential for a win/win outcome, and the US President’s recently announced delay to the increase in tariffs is a good sign in this regard. This is a possible result that does not get enough attention, although there is also a chance that trade tensions could worsen. Given the early signs of a global economic slowdown, that would be very unfortunate.

However even if trade breakthroughs do prove intractable, it’s not all bad news, with some potential for a positive economic performance during 2019 in the Asia Pacific region remaining.

The sharp fall in oil prices in recent months is a big plus for the region, and trade tensions could spur local policymakers into stimulus (providing short term support) and reforms (providing ongoing returns).

We hope common sense prevails on the trade front. If not, the best defence is a good offence: the smart way to navigate 2019 and beyond in the face of challenging geopolitics and tightening liquidity is for regional policymakers to get their own houses in order via further economic reforms.

Key issues: The Asia-Pacific region in 2019

After a phase of quiet recovery and progress in 2017, and a year of growth in 2018 that went almost unnoticed between pessimistic economic headlines, uncertainty overshadows the Asia Pacific region this year.

The trade tensions between China and the US are casting the longest shadow, with the general unsettlement of this situation causing ripples in market performance, interest rates and other indicators. But while the trade tensions are the main feature, they are certainly not the only story in this varied region.

There are two important questions on the table for 2019 for both policymakers and investors:

- Is a win/win solution still possible? Given the deep bilateral relationship between the US and China, will Beijing and Washington be able to strike a grand bargain on trade and broader issues?

- How will the Asia Pacific economies fare in the meantime? This region’s economies are at vastly different stages of development. How are they positioned given this uncertainty?

Is win/win a possible option between the US and China?

The trade tensions between the U.S. and China will be the most significant factor affecting regional economies and, even more so, financial markets in the Asia Pacific region.

If all goes well, a resolution of the trade conflict – even a temporary truce – could not only provide fresh impetus to domestic reform in China, but also remove a massive overhang for the region’s markets.

Ultimately, the US and China share a common interest in seeking to avoid a global economic downturn, the risks of which have grown. In the US, the financial tightening and loss of confidence caused by corrections in the US stock market coupled with an inverted yield curve have increased fears of a slowdown, which would be a concern for the US administration.

Similarly, the unintended consequences of Beijing’s unfinished battle of deleveraging and a continued impasse in trade talks could cause the Chinese economy to falter.

For a successful resolution, there are short-term issues (imbalances and market access) and long-term issues (such as the possible spill-over effect of China’s industrial policies and forced technology transfers) on the Chinese side, each of which needs to be addressed separately.

Short-term issues could be resolved through greater imports of US products and limited deregulation in certain sectors, such as financial services, healthcare and auto. However, greater purchases of US imports may result in trade friction with other trading partners. In the short term, the best policy response for China is to slash import tariffs significantly.

In the medium term, China must address the thorny issues of Intellectual Property rights (IPR) protection and perceived forced technology transfers. The lag in terms of IPR protection could be compensated for by faster liberalisation, especially by relaxing Joint Venture (JV) requirements in sectors where profits remain sturdy. Again, the automotive and service sectors would be great places to start.

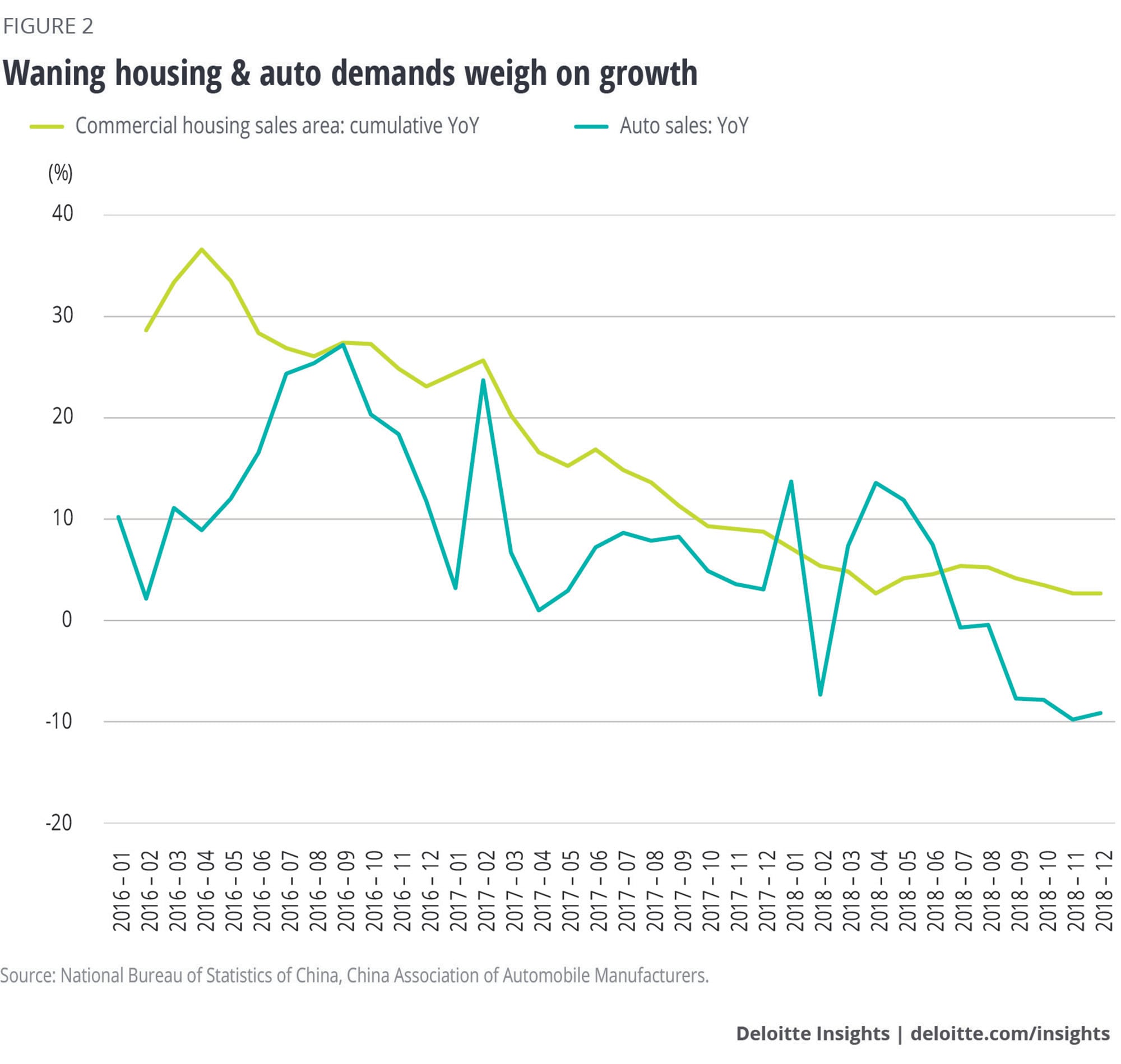

The auto industry remains highly fragmented even today. The 2018 auto-sales slowdown should have given policymakers a wake-up call, making it clear that further subsidies could only delay but not avoid the agony of consolidation. To help domestic carmakers make this transition, one solution would be to have greater fiscal outlays on social safety nets and job re-training for dislocated workers. Decisive action on relaxing JV requirements would send a powerful signal that China is committed to making the domestic market a genuinely open and fair place.

The best-case scenario for the US-China trade war would be for China to accept the 25 percent tariff on $50 billion of exports and open its domestic market in a meaningful way.

The worst-case scenario is a continued impasse, weighing heavily on both stock market sentiment and private investment. That would also make it increasingly difficult for Beijing to execute certain much-needed domestic reforms, such as relaxing joint venture (JV) requirements in certain sectors and increasing foreign ownership in the financial sector. In this case, a lower RMB exchange rate would boost exports and loosen monetary conditions.

The best way for the world economy to avoid losing its two key economic locomotives in a single swoop?

- China should meaningfully improve access to its market and address some of the outstanding contentious issues raised by the US and its allies (such as perceived forced technology transfers). That would directly ease some US concerns and generate worthwhile domestic reforms for China.

- With China moving on the above issues, the US could back away from using trade pressures to force Beijing to change core features of its development model.

Such an approach could restore some degree of trust and the region’s markets and economies would benefit from reduced risks.

Should miscalculations cause US-China tensions to escalate, most Asia Pacific economies are likely to suffer. Even if there were eventual benefits to selected ASEAN economies such as Thailand and Vietnam through relocation of manufacturing out of China, the overall damage to the region would be substantial over the longer term.

Economic developments beyond trade tensions

In this publication we try to look beyond the hype and the headlines. Despite much of the media coverage signalling challenges for the global economy, overall, as we predicted in edition four, 2018 was an economic success story throughout the region. Most economies held up well despite the deepening uncertainty created by US-China trade frictions.

As usual, markets moved more than economies. With global liquidity tightening, financial markets reacted disproportionately to this uncertainty. Stocks and currencies across the region were sold off amid a proliferation of geopolitical concerns, worries about disruptions to supply chains and other risks that were almost impossible to quantify.

In our view, interest rates are likely to continue rising in the US while other major central banks are also likely to cut back on their quantitative easing and financial liquidity will continue to tighten.

Even if US-China trade tensions subside, this gap between still-decent economic growth and market performance is expected to continue in the region in 2019.

If the recent easing in growth continues and trade tensions flare further, Asia Pacific policymakers may well have to resort to raising spending and/or cutting taxes. The paths they choose will vary, based on factors such as how dependent their own economies are on trade.

Given the region’s dependence on trade, these uncertainties caused by these measures could compel policymakers to respond by promoting regional trade integration. Both Tokyo and Beijing could provide leadership here.

Japan has already succeeded in realising an 11 country Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) after the US pulled out of the original TPP. It could help promote a new phase of expansion of the CPTPP since countries such as Thailand and South Korea have shown substantial interest in it.

China will probably move to facilitate a resolution to the faltering Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement that it is leading – and it might also try to find some points of convergence between this more expansive trade framework of the RCEP and the CPTPP.

As outlined above, an escalation in trade tensions between US and China would almost certainly cause a slow down for Asia Pacific economies. But even this dark cloud could have some silver linings.

In particular, there would still be wriggle room to support economic performance: regional policymakers could try to contain the damage through short-term measures such as a judicious measure of fiscal easing in the short term and supply-side reforms in the longer term.

In the near term, the economies are enjoying a respite from falling crude oil prices and there are few domestic imbalances that cannot be managed. That will give the region the space to address deeper structural challenges, particularly once the many elections in the region this year are out of the way. We say the best policy response in the face of challenging geopolitics and tightening liquidity is to get your house in order.

In our view, the Asia Pacific region in 2019 is likely to remain economically resilient with sufficient policy leeway to contain the risks.

Country forecasts

China: Measured stimulus and much improved market access

Overview

The consensus among most economic forecasters is that China’s economic growth in 2019, despite sizeable challenges such as trade tensions and the unfinished de-leveraging campaign, will achieve a respectable GDP growth rate in the range of 6.2 - 6.3 percent.

There are two main reasons for this.

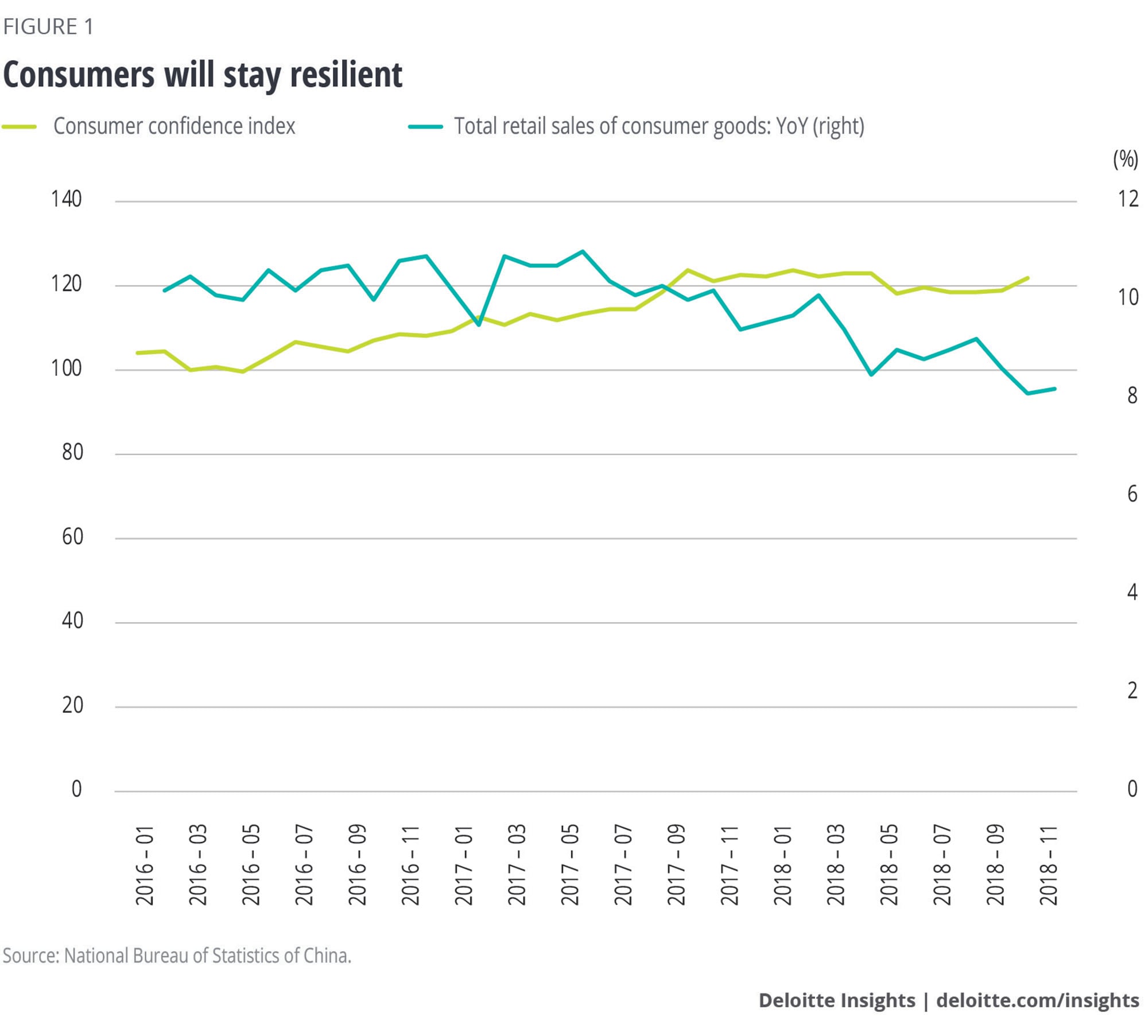

Firstly, barring a severe correction in the housing markets of major cities, growth in domestic consumption will probably be close to double-digits.

Secondly, even if there is a shortfall in exports due to trade tensions, this can easily be made up through a measured dose of fiscal stimulus, thus allowing domestic investment to make up the shortfall. The government has stepped up its efforts on the fiscal front already and we think China will probably have a moderate current account deficit in 2019. But the side effects of underwriting an unrealistic economic growth target and the terrible seductiveness of fiscal stimulus must not be underestimated.

China’s economic deceleration, which started in Q2 of 2018, became more apparent in Q4. There are several reasons:

- The deleveraging campaign greatly reduced access to bank lending. Private enterprises had to resort to other funding avenues such as stock-mortgage loans and with investor sentiment low, private investors were slow to come forward. One cause could be that recent government discussions on mixed ownership reinforced the idea that SOEs must stay big and strong, fanning fears of quasi-nationalisation.1 However, the government has since made it clear that the key policy focus this year will be reassuring private enterprise and bolstering its confidence.2

- The housing market saw significantly reduced transactions on the back of a slew of restrictive policies last year.

- The automotive sector, a bellwether industry in China, encountered some serious difficulties in 2018 as sales saw their first ever decline.

The end-of-year slowdown in the housing and auto sectors could prompt policymakers to unleash a fiscal stimulus package to kick-start economic growth. For the housing market, an easing of restrictive policies is on the cards – despite the official ‘homes are for shelter, not for speculation’ line3 – because, between worsening affordability and stagnation in the market, the latter is a far greater worry for policymakers.

As for the auto industry, whether the government will unveil more tax rebates to spur sales depends on the outcome of the next round of US-China trade talks. So far, Washington has deferred its plan to raise the tariff on $200-billion of Chinese imports, while China is going ahead with its rollback of tariffs on US cars and auto parts.4

China has also stepped up the purchase of US soybeans and other agricultural products.5 Given these encouraging signs, a truce may be on the cards in Q1 of 2019. Moreover, if the US equity market turns bearish amid fears of a possible slowdown in China (think Apple’s recent announcement6), the US administration might be more eager to strike a deal with China. Managing those trade tensions with the US is the real challenge, with both long-term and short-term issues to be addressed as outlined above.

On fiscal policy, a lower GDP growth target is an easy and efficient way to avoid over-capacity and other spill-over effects of China’s industrial policies. With hindsight, one can see that China’s massive fiscal stimulus package in 2008 did save the world economy by boosting commodity prices and market sentiment,7 but China’s rapid gains of market share in the manufacturing sector may have also fanned the fires of Western protectionism.8 Deloitte believes that if policymakers feel compelled to rely on an expansionary fiscal policy to cushion external shocks, the emphasis should be more on social development (healthcare, education and low-income housing) than on infrastructure.

On monetary policy, if the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) stays on its present course of monetary tightening, China is likely to face greater constraints in 2019, causing repercussions in the Asia Pacific region. Because the Fed is more interested in normalising short-term interest rates and less concerned about stock market valuations, it will probably stay its present course. Hence, in the medium term, interest rate differentials between China and the US will widen, again putting more pressure on the RMB. That said, a flattening or inverted yield curve of US interest rates prompted by fears of recession could reduce the pressure on the RMB. How China manages its exchange rate will be watched closely by regional policymakers and must be handled correctly.

If China wants to reflate the economy while avoiding a 2008-style fiscal stimulus, given the relatively benign inflationary outlook and the pullback of crude oil prices, Beijing could consider lowering the value of RMB against the dollar.

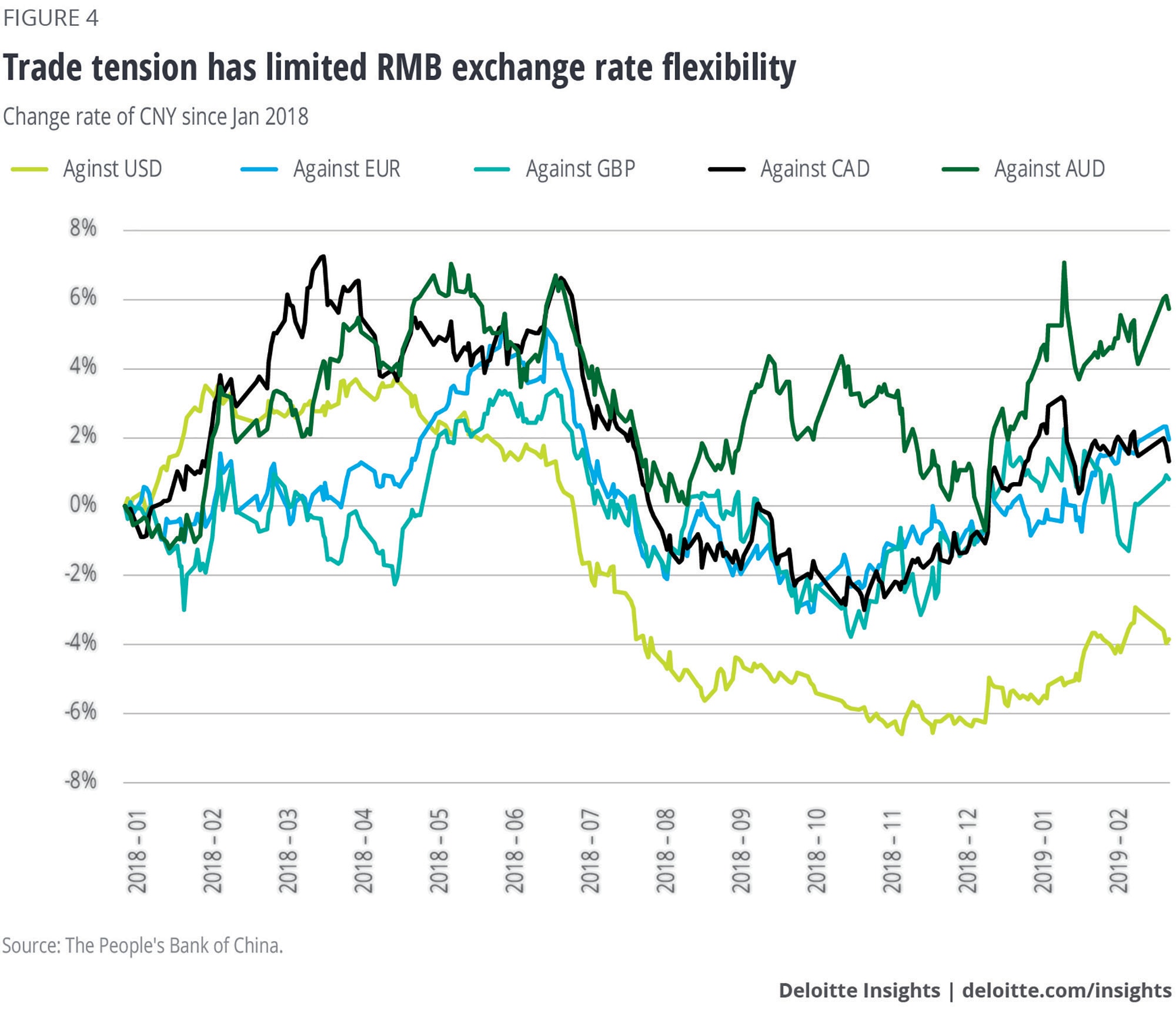

Outlook for the RMB and regional implications

The RMB will most likely continue its gentle slide against the dollar in 2019 but stay fairly stable relative to the currencies of China’s other major trading partners. The only wild card is the progress of the US-China trade talks. Even a temporary suspension of conflict would improve the rather subdued sentiment in China and the region, triggering equity rallies and bolstering battered currencies.

Unfortunately, the RMB exchange rate is often affected more by politics than economics. Beijing’s decision to keep the RMB stable during the Asian Financial Crisis propelled China into a position of leadership in the region. As long as trade talks continue, Beijing will keep the exchange rate steady as a gesture of goodwill. Meanwhile, despite the various mechanisms that enable the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to have a managed floating exchange rate regime, policy biases have increasingly favoured a stable RMB exchange rate since the second half of 2018.9 Rightly or wrongly, an exchange rate of 7.0 RMB to the US dollar is seen as a key psychological threshold in terms of confidence,10 even though the PBOC’s reserves stood at $3.07 trillion at the end of 2018.11

The real issue is whether a stable RMB exchange rate would come at too high a price, i.e., lead to sub-par growth or become a drag on corporate profitability. Deloitte’s long-held view is that China does not need a major depreciation of the exchange rate to restore competitiveness. However, a slightly weaker RMB will support the PBOC’s accommodative monetary policy and reduce some of the pains of de-leveraging.

If China were to accept a 25 percent tariff on $50 billion worth of exports to the US12, this could be offset easily by some export tax rebates and the mild RMB depreciation.

A successful outcome also implies that China will keep the RMB exchange rate relatively stable amidst persistent downward pressure.

Interest rate differentials will favour the dollar unless the US economy experiences a much worse-than-expected slowdown in 2019. What has motivated both the Fed and the European Central Bank (ECB) to raise interest rates is their desire to normalise short-term rates rather than their fear of inflation. Deloitte’s US economist envisages one or two interest rate hikes by the Fed in 2019. Meanwhile, the PBOC would like to keep monetary conditions loose, at least by cutting reserve requirement rates (probably twice this year).

In theory, China could engineer a moderate revaluation of the RMB such that the expectation of depreciation could be met or even exceeded. In practice, it is almost impossible to know where to stop. To maintain a stable RMB exchange rate while allowing interest rate differentials with the US to widen would bring distortions in the economy and increase the administrative cost of implementing capital controls.

Also affecting the RMB outlook in 2019 is deleveraging. As this will be a multi-year project and cannot be done without pain, the debt/GDP ratio must come down through a combination of economic growth, inflation, and debt workout. Other countries’ experience of debt reduction suggests that slightly higher inflation will make it less painful. This would imply a weaker exchange rate. China has many tools to stabilise the RMB in 2019 and even beyond, but the issue is at what cost?

On balance, we believe a slightly weaker RMB will bring greater economic benefits than maintaining a stable exchange rate. This may worry the other Asia Pacific economies, but if the exchange rate depreciates by five percent against the dollar in 2019 (see the section on Southeast Asia and India), the impact on regional economies will be manageable if China avoids abrupt revaluation. Unlike 1997, when emerging Asia was severely hit by drastic outflows of capital, most economies are in much stronger positions in their balance of payments and fiscal positions.

If Beijing can strike a balance between de-leveraging and economic growth, then a softer RMB exchange rate, so long as it is not a significant revaluation as in 1994, will have little impact on regional economies.

India and South-East Asia

Overview

As 2018 drew to a close, India and South-East Asia confronted two burning issues: first, the trade tensions between China and the US and second, domestic structural reform.

The overall picture for ASEAN economies in 2019 is reasonably good. The South-East Asian nations are more exposed to the downsides of a trade war and could suffer material slowdowns in exports and investment, even as, on the domestic front, they seek to overcome various constraints on economic growth.

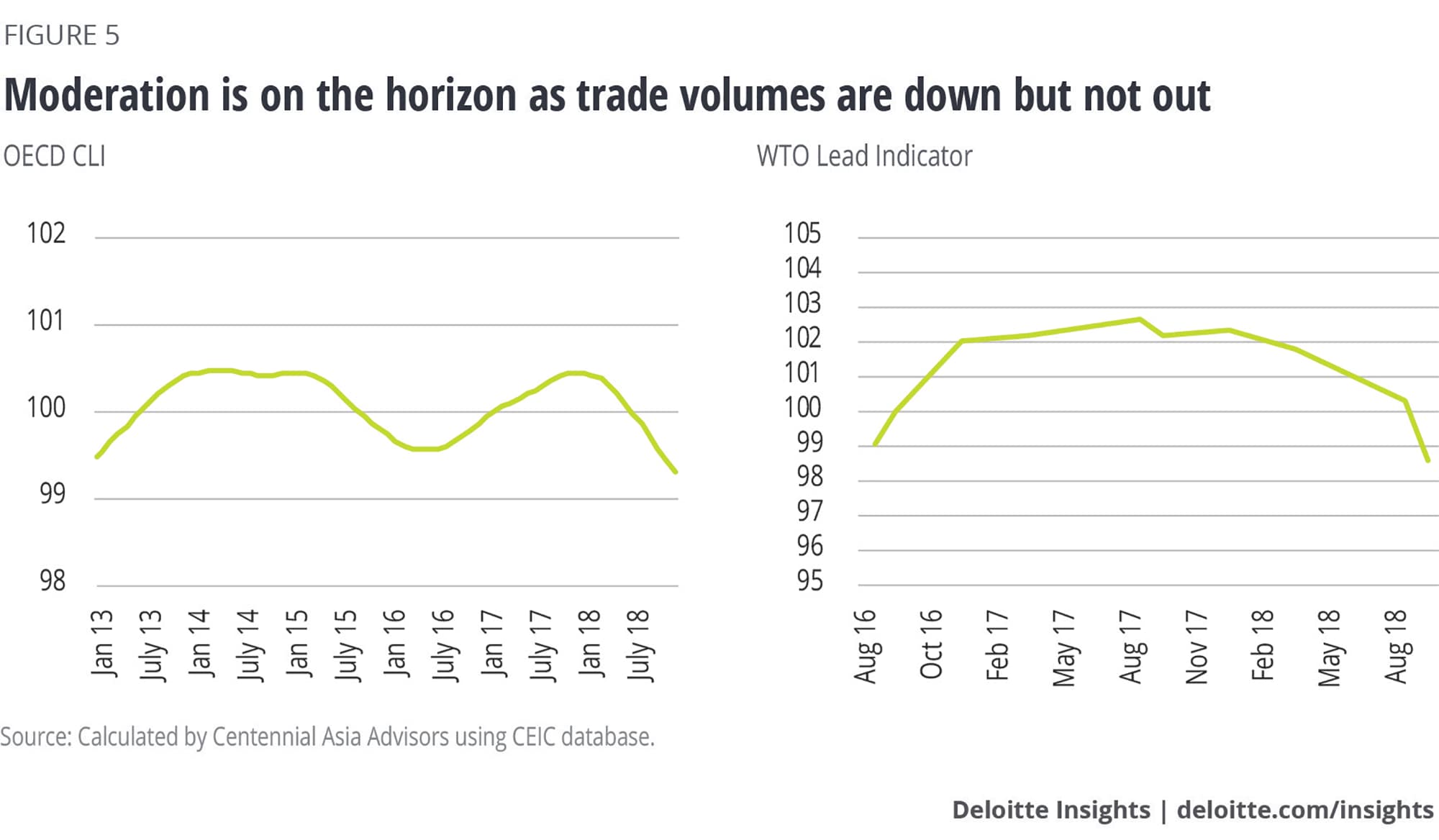

While global growth is slowing, the baseline case is for only a modest deceleration. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its January 2019 update, sees global economic growth at 3.5 percent, a tad less than the 3.7 percent of 2018. Chart 5 shows that the OECD lead indicator supports the case for global growth to moderate to just below a trend pace. Chart 6 illustrates that the all-important spill over into demand for the region’s exports through the trade channel also shows a manageable deceleration

A full-blown trade war

A US-China trade war would produce a drop in demand for intermediate goods exports from South-East Asian countries whose exporters are integrated into China-centred supply chains.

If investors start to believe that the trade war is a longer-term proposition, the consequences will be more severe for investment and business confidence. Global investors will become even more risk-averse, resulting in a substantial withdrawal of funds from regional bond, equity and other financial asset markets across the Asia-Pacific. That could also spark currency market pressures. As business confidence (especially in the trade-dependent ASEAN economies) falls, both domestic and foreign direct investors would defer or cancel hiring and investment plans, producing an even greater slowdown.

Another risk to South East Asia is China’s economy, which is slowing not only because of the trade tensions but of domestic factors.

Overall, we expect growth rates to decelerate slightly across most South-East Asian economies, although the impact of elections and monetary pressures in several could muddy the waters.

A slowing China

A slowdown in China could result in fewer Chinese tourists or Chinese students seeking to study in the region. Moreover, China is the single most important determinant of economically sensitive commodity prices that are key to the economic health of South-East Asian countries, falling prices such as for thermal coal, base metal and rubber could hurt.

China’s policy response to a slowdown will have important consequences for ASEAN and India, especially its approach to its currency. If the RMB were allowed to slide to, say, 7.3 against the US dollar, the shock to regional financial markets would be substantial. Panic selling, especially of more vulnerable currencies such as the Indonesian Rupiah and the Philippines Peso, could cause much damage.

If China implemented a depreciation in a gradual and measured fashion, telegraphing its intentions well in advance, the impact on ASEAN and India’s currencies would be more orderly and modest.

India

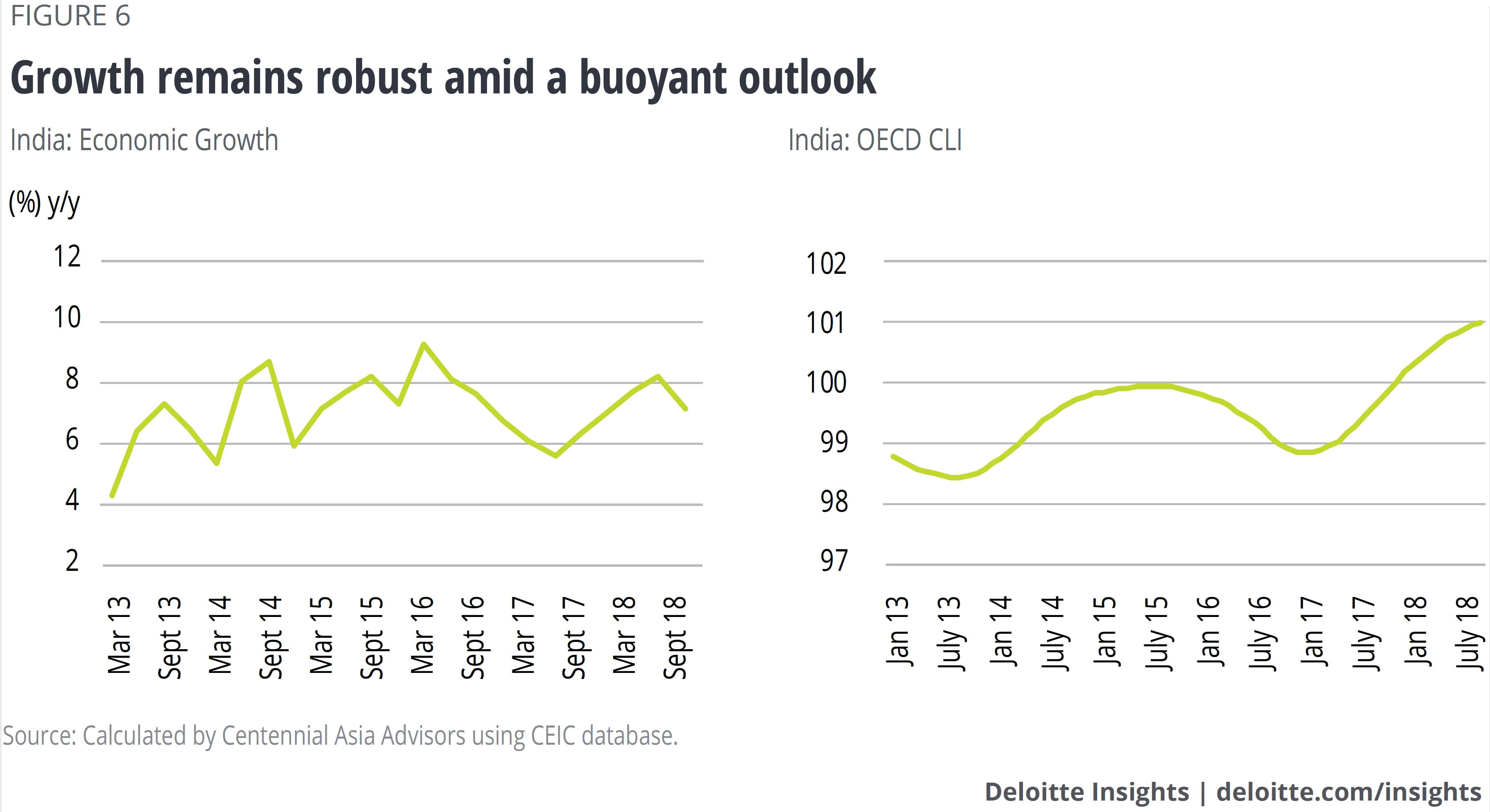

India would be less impacted by these downside risks because it is less reliant on upstream manufacturing. GDP growth in India is expected to hit 7.5 percent in 2019 with its economy rebounding after the shocks of demonetisation and the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax.

Moreover, we have seen a decline in the liquidity crunch generated by stresses in non-bank financial institutions, which will mean greater financial support for smaller businesses. Falling oil prices coupled with infrastructure and pre-election spending pledges and the many handouts in February’s budget – including income support for farmers, a new pension scheme for workers in the informal sector and tax breaks for the middle class – will also provide a buffer to the Indian economy.

The ASEAN economies

The ASEAN economies will continue to benefit from supply side reforms to improve the ease of doing business, increasing their competitiveness. Lower oil prices will add to the positive outlook as most countries, apart from Malaysia, are net importers of oil and will benefit from the global growth resulting from easing oil prices. All this, together with a surge in spending on infrastructure, should strengthen the region’s resilience to external shocks.

Indonesia

Indonesia’s economy is expected to grow at around 5.2 percent despite the impact of a 175-basis point rise in monetary policy rates in 2018. Spending by confident consumers, infrastructure spending and an anticipated pre-election spending spree will offset the rate rise.

Indonesia remains vulnerable to financial market pressures because of its current account deficit, which rose to 3.6 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2018. However, the deficit will probably ease to just below 3 percent of GDP as investment demand slows in response to higher interest rates and this slows the growth of imports of equipment. Moreover, the high foreign ownership of its bonds and equities exposes it to abrupt capital outflows whenever global investors turn more risk-averse.

Despite this, Deloitte predicts a more resilient Indonesian economy. Sound fiscal and monetary policies will contain the current account deficit in 2019 while keeping inflation low.

Vietnam

The outlook for Vietnam is more positive. Vietnam’s GDP grew 7.1 percent in 2018 and is likely to maintain that vibrant pace in 2019 Production relocation13 from China to avoid rising labour costs and potential trade war complications, coupled with strong domestic and foreign investment approvals will mean major growth in manufacturing and construction. Rising wages and expanded business opportunities will also generate higher consumer spending and expansion for Vietnam’s real estate sector. Over the medium term, though, Vietnam needs to work harder at reforming its banks and reducing the risks of non-performing loans.

The Philippines

Growth is expected to decline slightly in the Philippines from 6.6 percent in 2018 to between 6 and 6.2 percent this year. Business-process outsourcing and foreign remittances are forecast to grow less quickly but that should be offset by government spending in the run-up to mid-term Congressional elections in May.

We anticipate that these factors will be mitigated by the delayed impact of the sharp interest rate hikes in 2018. The Philippines also suffers from uncertainty around how tax and other proposed economic reforms will affect business.

Thailand

In Thailand, GDP growth is tipped to remain steady at just below 4 percent thanks to production relocation from China, infrastructure spending, pre-election government spending and lower oil prices. After the election in late March, experts believe business uncertainty will recede and private investment will rebound. Tourism will continue as a major source of economic growth for the Kingdom.

Malaysia

The Malaysian economy is set to benefit from a spike in consumer and business spending when the government releases some $US4.5 billion worth of unpaid GST rebates. Growth in Malaysia should remain stable at around 4 to 4.5 percent in 2019 as the new government provides more clarity to encourage business investment. External demand is also tipped to increase in line with global growth.

Singapore

In Singapore, an expansionary budget will combine with new policies aimed at improving demand for its regional hub services such as finance and transportation. These should help maintain economic growth at slightly below the 3.3 percent achieved in 2018.

The port city’s terms of trade and economic bottom line will continue to flourish thanks to its booming entrepôt hub and its close connections with neighbouring Indonesia and Malaysia, while India’s economic acceleration in 2019 will also help.

Japan

The key issues for Japan in 2019 will centre on US-China trade tensions; the drivers for Japan’s economic growth; the Bank of Japan’s ability to manage any larger-than-expected revaluation of the Chinese RMB; and what measures ‘Abenomics’ has in store for Japan’s economy.

The country’s strong footprint across ASEAN economies, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, will provide some protection from the negative fallout of any US-China trade war.

Stimulus on the Chinese side would also mean an increase in demand to the benefit of Japanese firms doing business in China’s domestic market.

Deloitte believes that the impact of the growing trade tensions between the ‘big two’ will vary depending on the business strategies of individual companies. Many Japanese executives are already developing strategies for a worst-case scenario.

Any global slowdown flowing from a trade war could have serious consequences for Japanese traders and exporters on the back of a decline in exports during the third quarter of 2018.

Japan’s GDP growth is expected to be flat during 2019, falling in the 1 to 1.2 percent range as the economy struggles under the strain of a government debt level sitting at 226 percent of GDP.

A key plank of the Abe Government’s Yen100 trillion package of budget measures is an increase in the VAT in October from 8 to 10 percent under the next round of ‘Abenomics’ that will generate a spike in domestic demand towards the end of September.

In addition, the government is planning a 2.3 trillion Yen ($US18B) fiscal stimulus package to offset the downside impact of the tax increase on households. The package will include increased government spending and lower taxes on cars and housing.

The last jump in consumption tax in 2014 from 5 to 8 percent generated a significant downside impact, but we do not think the same negative impact will occur in 2019. It is expected to be rather moderate due to tax relief measures set up by the government along with the fiscal stimulus.

The trade-off between the increased consumption tax and the stimulus package and the one-time hike in demand should offset each other, resulting in a 1.1 percent growth rate.

While the government is targeting a 2 percent inflation rate during 2019, we believe that is unrealistic given the risk of a global slowdown and falling oil prices.

High government debt levels continue to pose a sovereign risk but that is offset by the Bank of Japan’s strategy to purchase huge quantities of government bonds as part of the quantitative easing policy. The bank now owns 45 percent of the outstanding stock of government bonds.

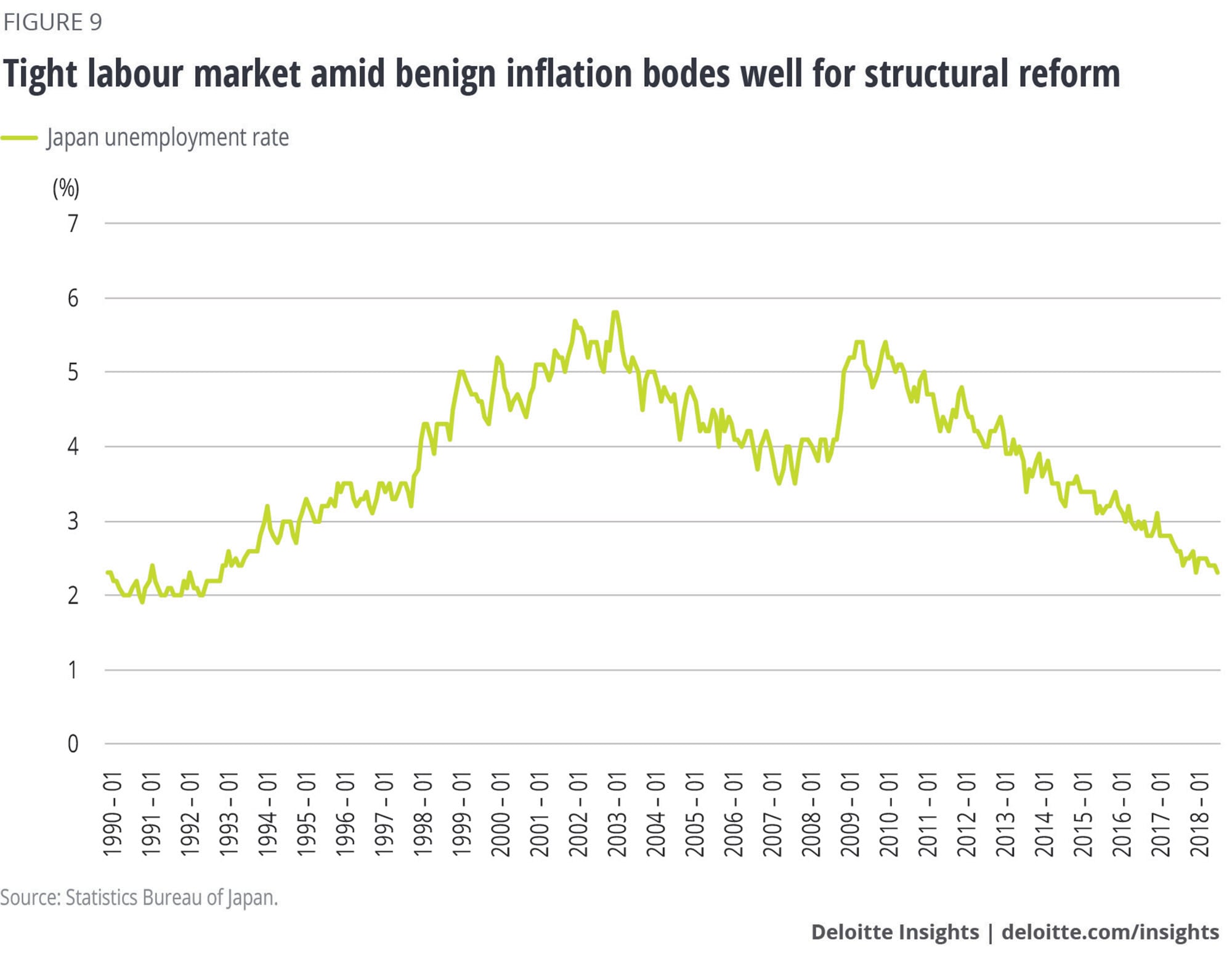

Unemployment in Japan is at historic lows at around 2.5 percent and we expect this to remain at 1990 levels during 2019. The ratio of job openings to applicants has risen to its highest level since 1974 and the ageing and shrinking population remains a major challenge.

The government will be under pressure to further reform the labour market by removing obstacles to employment for older citizens including lifting the mandatory retirement age above 60 years.

The labour shortages combined with capacity shortfalls and record corporate profits stimulated business investment.

Given the economic slowdown predicted in the year ahead, the market will pull money from risky assets, resulting in an appreciation of the Yen.

The dollar was sold off towards the end of 2018 and the currency began this year at 108 Yen to the $US. The $US-to-Yen rate will probably fluctuate between 95 and 110 throughout 2019.

The 10-year yield for US bonds is 2.7 percent compared with 3 percent during 2018, reflecting the recent turnaround of monetary policy stance by FOMC towards more dovish and “patient”.

In summary, we expect the slowing global economy to flow on to Japan with growth to remain stagnant at about 1 percent.

Australia

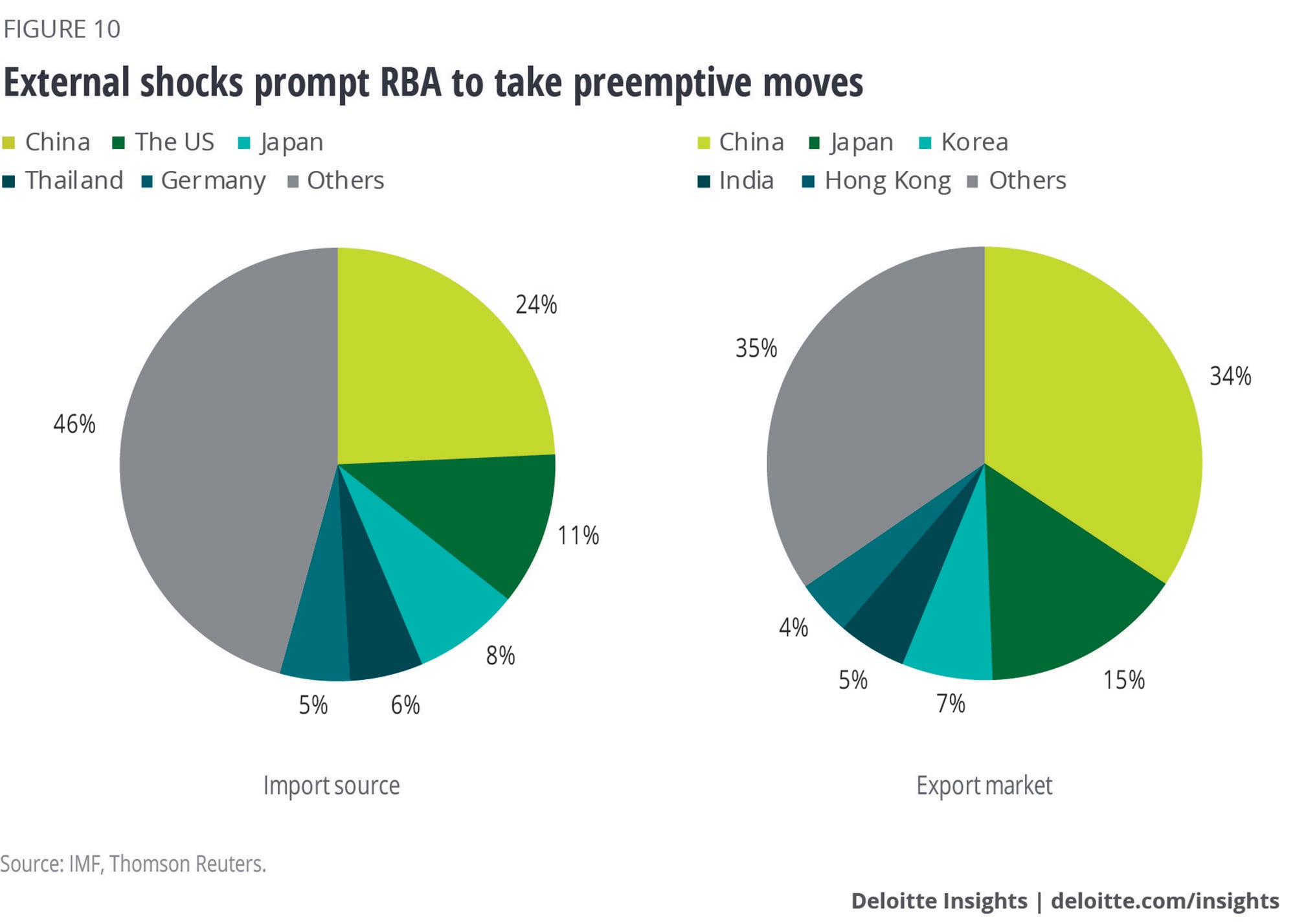

The specific impact of the China-US trade impasse will be more muted in Australia, where the size and scope of tax cuts in the US and the pace of global growth are much more significant economic factors when it comes to the resilience of the local economy.

China is very important for Australia in a trading sense, but Deloitte believes trade is unlikely to be the trigger for any major slowdown during 2019.

China has been growing rapidly for many years on the back of infrastructure investment and debt. A necessary, gradual realignment toward consumption and services in China is a long term positive for the Australian economy. A more marked slowing of the Chinese economy, especially in the housing, corporate bond and shadow banking sectors represent greater threats to Australia than the trade war.

While Australia’s broad economic fundamentals remain favourable, there is also expected to be a modest slowdown in economic growth for Australia during 2019.

The pace of growth has been regarded as quite good and growth in the order of 2.5 percent for the next two years is likely.

We regard growth numbers with a ‘2’ in front of them as a solid performance during 2019, particularly with the housing market posing a significant economic risk.

House prices in some major cities in Australia have exceeded underlying fundamentals for some time. A correction is now underway and is expected to continue through much of 2019.

However, there is potential for the housing correction to spill over into consumer spending and broader sentiment in the economy as financiers tighten lending practices amid low wages growth.

The drought that has affected large parts of the country’s interior is also weighing on activity and creating significant hardship in some regional communities, as have floods and bushfires early in Q1.

Nevertheless, the Australian economy is being somewhat cushioned from the housing downturn by infrastructure investment flowing from state government coffers that are awash with revenue from stamp duty collected during the housing boom, although that spending is expected to peak this year.

The Commonwealth Government’s finances are also in their best shape for a decade and an earlier-than-expected budget surplus is expected.

With a federal election due in the first half of this year, the budget is likely to include fiscal stimulus in the form of modest tax cuts and increased government spending.

Commodity prices are unlikely to rebound significantly during 2019 and while prices are up slightly, the heady days of the commodity price boom are behind us.

Official interest rates are on balance expected to remain stable during 2019, the Reserve Bank of Australia dampening expectations of a rise in its February statement on monetary policy. At the same time, increasing US interest rates will put pressure on the Australian dollar, with the risks to the downside for the value of the $A through 2019.

Overall the story for Australia during 2019 will be one of ‘steady as she goes’ as the economy responds to the burning questions that will have a much greater impact in China and South-East Asia.

Conclusion

In summary, the Deloitte view is that the Asia-Pacific region is reasonably well placed to hold its own economically in the Year of the Pig, in the absence of any major shocks resulting principally from the US-China trade tensions.

Geopolitical friction and political personalities notwithstanding, the economies have shown an ability to remain resilient despite the uncertainty surrounding the US-China relationship.

In the environment of a continued slowing in global growth, the Asia Pacific economies – which are at vastly different stages of economic development – also have tools at their disposal to help themselves.

These include applying their own domestic micro-economic levers and, externally, committing to strengthening regional trade integration.

It is more likely than not that cooler heads will prevail as the US and China each confront the real risks to their own economies of a failure to reach a common understanding, or at least a workable set of arrangements, on trade.

In the meantime, the Asia-Pacific countries need to continue making progress with their own sensible economic reforms.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more economics content

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article4 days ago

-

US Economic Forecast Collection

-

Economics Insider Collection

-

Issues by the Numbers Collection