Ageing Tigers, hidden dragons has been saved

Ageing Tigers, hidden dragons Voice of Asia, Third Edition, September 2017

15 September 2017

Asia as we know it will rapidly change shape over the coming decade, with demographics set to drive huge changes in growth momentum in our region. Asia’s third wave of growth is set to begin, stirring hidden dragons, while ageing Tigers must face the challenges and opportunities of an older population.

The first wave of growth in Asia saw Japan’s relative "people power" peak in the 1990s, while China’s people power sprinted for four decades and generated a second great wave of growth in Asia, before peaking at the start of the current decade.

Explore the issue

Demographics fuelling Asia’s shifting balance of power

Asia’s growth on the cusp of change

Demographics under the spotlight, by country

Voice of Asia is also available in:

That second wave rewired the world economy more significantly than any other event since the industrial revolution.

Now the third great wave of Asia’s growth is beginning, one that will cement us as the centre of the world’s economy and its growth.

Figure 1.1 shows the rise and fall of the working age population (those aged 15-64) as a share of the total population of Asia’s three biggest economies1. This simple ratio of workers (productive potential) to total population (demand) is marvellously predictive.

As these two waves begin to recede, the figure shows they will be replaced by Asia’s third wave, with India’s contribution to global growth increasingly set to rise to the fore, well supported by the likes of Indonesia and the Philippines.

The demographic dividend

Asia’s tides are turning. And these massive demographic tides in countries such as India, the Philippines, and Indonesia will drive more growth than generally realised.

The great waves shown in figure 1.1 essentially map the ageing process. But these waves aren’t just a cause of economic change; they’re also a symptom.

Nations get older for a reason—ageing happens because birth and death rates both fall as nations get richer:

- When people are poor, having more children is both insurance against the child mortality rates seen in poorer places, and also insurance for aged care—that there’ll be someone to take care of you when you can’t take care of yourself.

- As nations get richer, different things happen, including greater spending on training and education, and a fall in birth rates, which creates the opportunity for more women to work, as well as a rise in life expectancy that encourages people to work for longer.

They are the additional accelerators of growth for the countries on the rising side of the wave but they could also be the decelerators of growth for the countries on the declining side of the wave. These factors, as well as different speeds of getting richer, aren’t captured in figure1.1—they alter the size of the labour force (the share of the population that would take a job given the opportunity) differently than the change in working age population.

But they do travel alongside those background demographic trends. And, if given the chance, these additional factors typically add to each country’s productive capacity.

That says there’s a potential virtuous circle: Improving demographics are usually accompanied by (1) increased productivity thanks to a better-trained workforce and, in the case of some countries, that is accompanied by (2) increased participation within the working age population as more women work, and (3) growing workforce participation outside of the traditional 15 to 64 age group as retirement ages start to rise.

(Some of these trends will, of course, be partially offset by other factors. For example, while education boosts productivity, it will often lower workforce participation as young people delay their entry into the market as they undertake higher education.)

So, for example, the lift in Japan’s relative people power through the 1950s and 1960s was occurring mainly thanks to the first factor. In Japan, the second and third factors came later, being the focus of policy amid declining demographics in order to mitigate the damages of a shrinking labour force.

In China’s case, we can also add a policy factor to these demographic impacts, with its one-child policy contributing to the speed of the initial wave of China’s relative people power versus that in other countries.

Equally, India’s contribution to the economies of Asia and the globe won’t simply be because of worker numbers or population alone but also because those gains will go hand in hand with increased productivity and participation, which have been realised by improving demographics.

Japan, land of the rising age—and disappearing worker

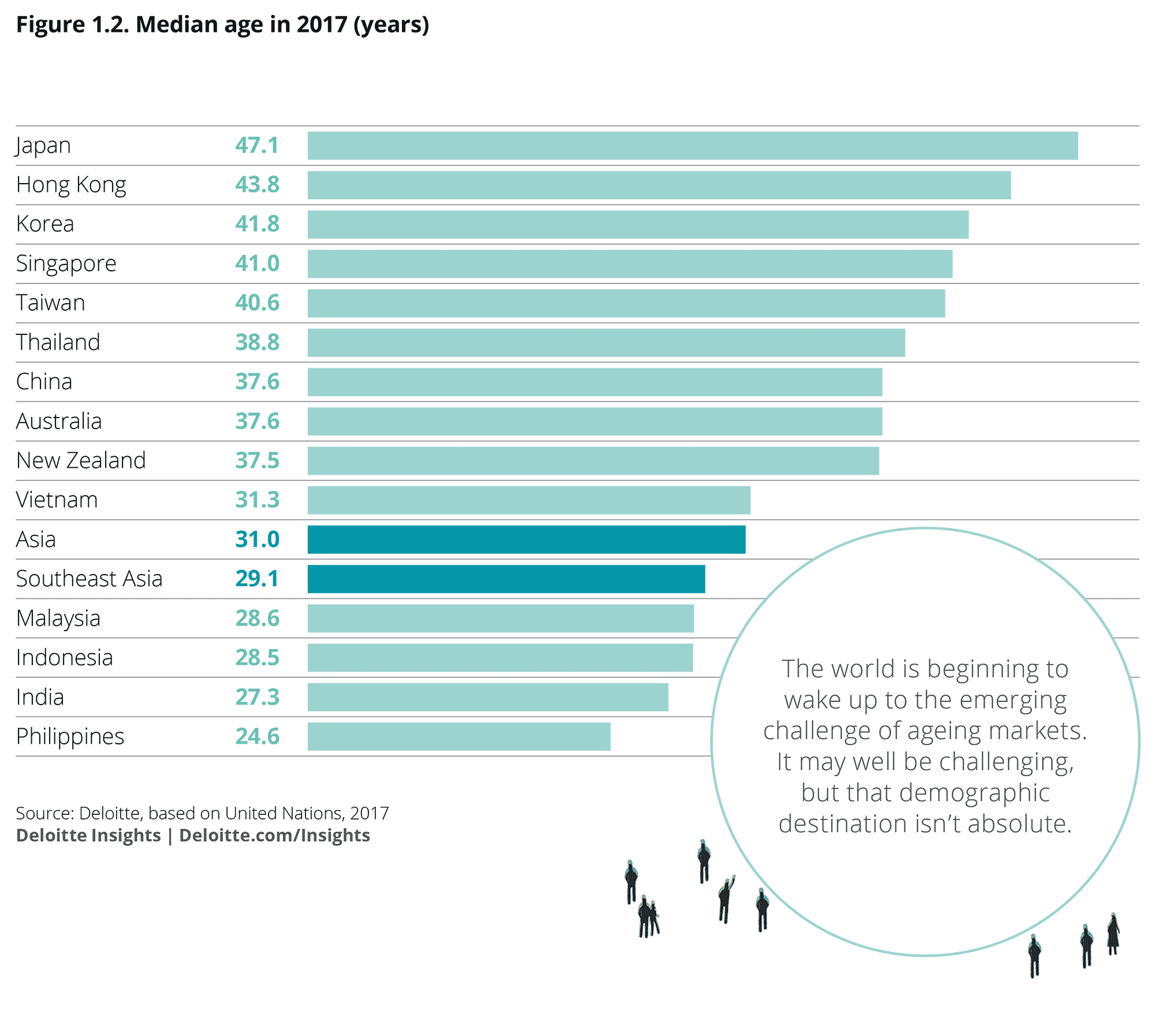

In the early 1990s, Japan surpassed Sweden as the oldest country in the world. In the quarter century since, its median age has leapt to over 47 years (see figure 1.2). The average resident in Japan today is 25 years older than in 1950.

This increase is to some extent driven by increasing life expectancy—Japan’s life expectancy is among the highest in the world. However, the average woman in Japan is having only 1.4 children in her lifetime—compared with 2.5 around the world—well below the 2.1 required to maintain population levels without assistance from migration.

The low birth rate (combined with low migration levels) is now cutting into the supply of potential workers in Japan. That measure—the population aged 15 to 64—peaked in the 1990s at around 90 million. It has already fallen to close to 75 million, and the latest United Nations projections suggest it will likely halve from its peak over the course of this century. This sort of decline is viewed by some as the real “population bomb”2 of the 21st century, dragging down rates of economic growth through ageing-driven recessions and by the increase in the number of retirees relative to the number of workers.

Japan’s rather unique immigration policy only adds to these effects. While many European and Asian countries facing ageing populations have adjusted their immigration policies to mitigate the problem, Japan has kept its door strictly closed to foreign workers and immigrants. One observation is that while this policy does not help ease labour shortages, it may still contribute to enhancing the cohesion of society (which helped to overcome national crises such as Japan’s March 2011 triple disasters of earthquake, tsunami and a nuclear meltdown). With many countries facing increasing social divides and unrest now reconsidering their open immigration policies, how Japan keeps or changes this unique policy may be a lesson for others.

The resulting ageing and declining population have been causing many problems for Japan, one of which is its declining potential growth rate. Japan’s potential growth rate has been constantly declining, from 3-4 percent during the 1980s to less than 1 percent a year from now, mainly owing to declining growth in worker numbers.

Another problem has been the worsening government budget deficit, caused in large part by rapidly rising spending on the growing number of retirees. Japan’s public debt is now more than double its annual national income—by far the highest in the world. As its social security system was designed assuming stable funding of the older generation by the younger generation, an ageing population risks the collapse of the system (without reducing the benefits for the old or increasing the contributions by the young). Japan’s ageing population also limits the potential for the political system to fix the problem, as the dominant older generation’s vote makes it quite difficult to transform the system.

Japan might be fortunate in that many of the more negative impacts of population ageing—notably, increasing health care expenditure—are lessened by the relatively healthy state of the populace (the Japanese take less medication than almost any other rich nation), but they are of course unable to avoid all of the issues around population ageing.

One rather unexpected problem of Japan’s changing demographics was that the great growth of the 1980s—and accompanying financial bubbles in its real estate and stockmarkets—misled companies, banks, and the government into thinking that the pace of growth would continue. This occurred even though demographic change is one of the easier events to forecast and prepare for. Still, the inertia of people’s mind-set, which is often accustomed to growing population over generations, makes it difficult for them to accept the new reality. In practice the demographic cycle turned, meaning that many investments failed to meet their potential, thereby adding to non-performing loans and deflationary pressures. This result is another lesson that other countries would be wise to take note of.

Ageing Tigers

What Japan has in averages, China trumps in scale. Indeed China probably already has more than 150 million people aged over 65, and the echoes of its one-child policy mean the next generation will be much smaller than would otherwise have been the case.

Much of the rest of Asia’s story will mirror that of China. That’s true, for example, of Thailand, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Korea. Like Japan, many of these countries have relatively high life expectancies and low rates of child birth (according to some measures,3 Singapore, Hong Kong, and Korea have three of the five lowest rates in the world).

This group of five will face similar demographic-driven challenges, and opportunities, to those of China. In fact, as figure 1.3 shows, they are almost indistinguishable in the tides of their demographic rise and fall.

That may seem strange, given that average incomes in China are a fraction of those of developed Asia. But that’s because China’s demographics, like much of the rest of the China story in recent decades, have been sprinting.

It usually takes longer for nations to get older, but China’s one-child policy accelerated that timetable. One of the key reasons why figure 1.1 saw China’s working population share rise higher than other countries was the lack of children born through the 1980s and 1990s, but that same lack of children (and the inability of the government to lift birth rates in recent years) will see a rapid reversal of those trends.

Countries typically get both rich and old in tandem, at least in part because ageing is a symptom of incomes. However, the acceleration of this process means China will get old before it fully succeeds in getting rich. This is yet to seep into the consciousness of most of the world, which still regards China simply as a country with an extremely large population.

Yet, the most recent update to the long-term population outlook for China has seen a sharp downward revision of the long-term size of its workforce. Despite moves to unwind the one-child policy, younger people do not need to be prevented from having more than one child; they may require significant encouragement to have any children at all.

The worst-case scenario would be if China followed Japan’s path, with declining growth, a worsening government budget deficit, and pressure on its property and financial markets.

If so, the global implications would be massive, given that China’s population is ten times that of Japan, and given that China doesn’t yet have a sound social security system. And there’s a chance that ageing, particularly in China, could lead to higher inflation rates and higher interest rates around the world. 4

In turn, that says the business opportunities opening up as a result of demographics—which we cover in the next article, Asia’s growth on the cusp of change, driven by demographics—will be different in China from those that can be expected in Thailand, Taiwan, Singapore, and Korea. All of these nations have enjoyed a remarkable run of growth over the past half century. And, as figure 1.3 shows, some of that economic expansion has been thanks to an underlying trend in demographic growth that has boosted the share of the population most likely to work.

But this trend is poised to reverse its direction. In China, Hong Kong, Thailand and Singapore, the working age population peaked as a share of total population a few years ago, while that demographic peak is happening pretty much now in both Korea and Taiwan.

This group may sit behind Japan in terms of the median age of their populations, but they are the next in line for ageing pain to hit their economies.

This tide will go out relatively fast. For each of these countries the next half century will not merely unwind the demographic gains of the last half century, it will see new demographic lows being hit. And although some of these effects will be slow, a number of them will travel at speed.

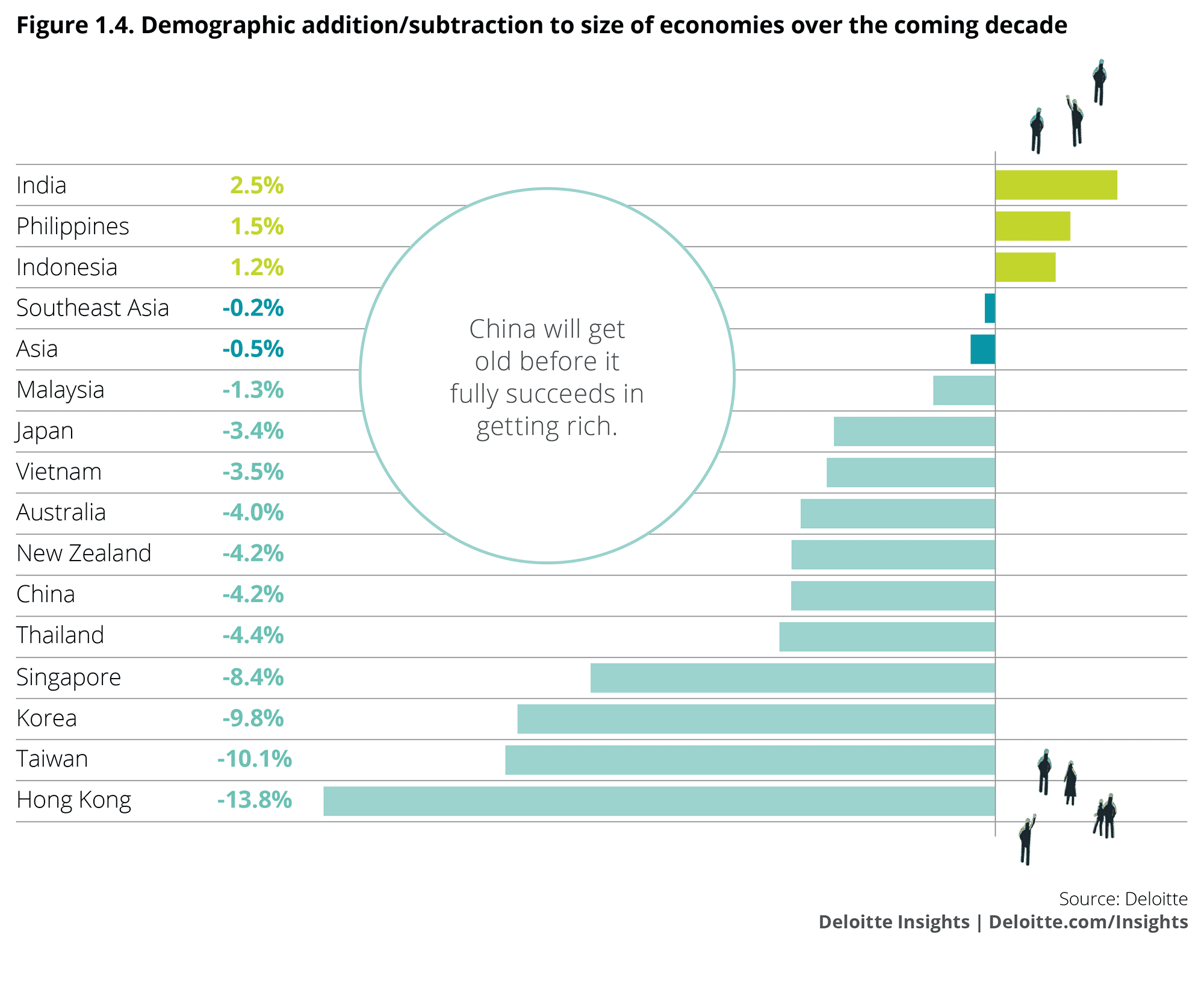

Figure 1.4 sets out the projected losses attributable to (or gains from) demographics. These calculations assume that, other things equal, the size of these economies will be:

- Proportionately larger where there’s a demographic dividend (India, the Philippines, Indonesia), and

- Smaller where working age populations will shrink as a share of the total between now and 2027.

The figure tells a remarkable story, but not a pretty one.

The group of economies considered in figure 1.3 are those most in the firing line. The backdrop to doing business in Hong Kong, for example, will change radically within a decade as retirees surge in number.5 The number of people in Hong Kong aged 65 and over will rise from just 1.2 million to 1.9 million by 2027, and 2.4 million by 2037.

At the same time, the number of children in Hong Kong (those aged through to 14) has already fallen behind the number of people aged over 65. In fact, Hong Kong has around one-quarter fewer children today compared to the 1980s. While births are finally on the rise, these past trends will limit future growth, with consistently fewer people starting their working lives than there are older workers retiring at the end of theirs.

To add to that quantitative problem, there is survey evidence suggesting a surprisingly high number of young adults would live elsewhere if they could,6 a qualitative issue further jeopardising the long-run pipeline of new workers.

Yet, although this story is particularly stark for Hong Kong, it doesn’t—or shouldn’t—overshadow what is starting to happen in Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. Each of these nations is also seeing the demographic tides turn sharply against them.

This group was lauded as Asia’s Tigers during the 1980s and 1990s. But from here on they are ageing Tigers, whose growth now lies on the wrong side of demographic destiny, and whose policy challenges will now rest on other growth drivers, including productivity-enhancing reforms, an openness to migrants, and a drive towards greater participation among women.

Aussies and Kiwis

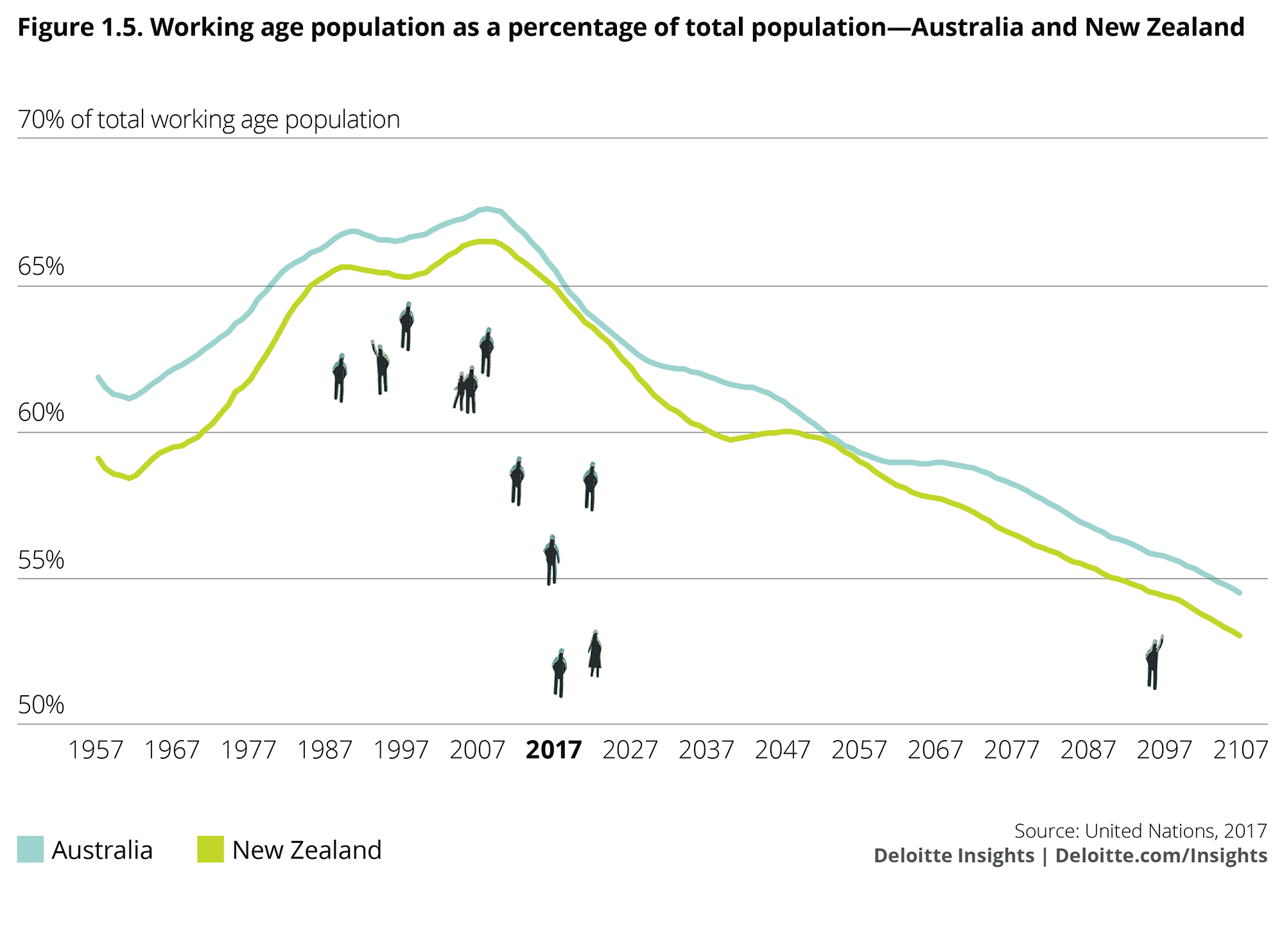

A glance at figure 1.5 shows another little-recognised fact: Over the coming decade, Australia and New Zealand will see demographic-driven slowdowns even larger than those being faced in Japan.

What gives? How is it, for example, that Australia shows up as more in the demographic firing line than Japan over the next decade?

The difference is simple: Japan has been feeling its demographic downdraft since the mid-1990s, with the last decade putting considerable pressure on that nation’s growth potential.

In other words, Japan has already faced the facts, whereas the pace of future pain is starting to go up for the likes of Australia and New Zealand, as well as in countries such as China and Thailand.

As the figure shows, by 2047 Australia will have lost all of the demographic-driven gains in the ratio of potential workers to total population made since 1961, and the same will be true of New Zealand by 2061.

The hidden dragons have demographics that look like India’s

As seen above, much of Asia’s demographic change across the rest of the century will match the trends seen in China.

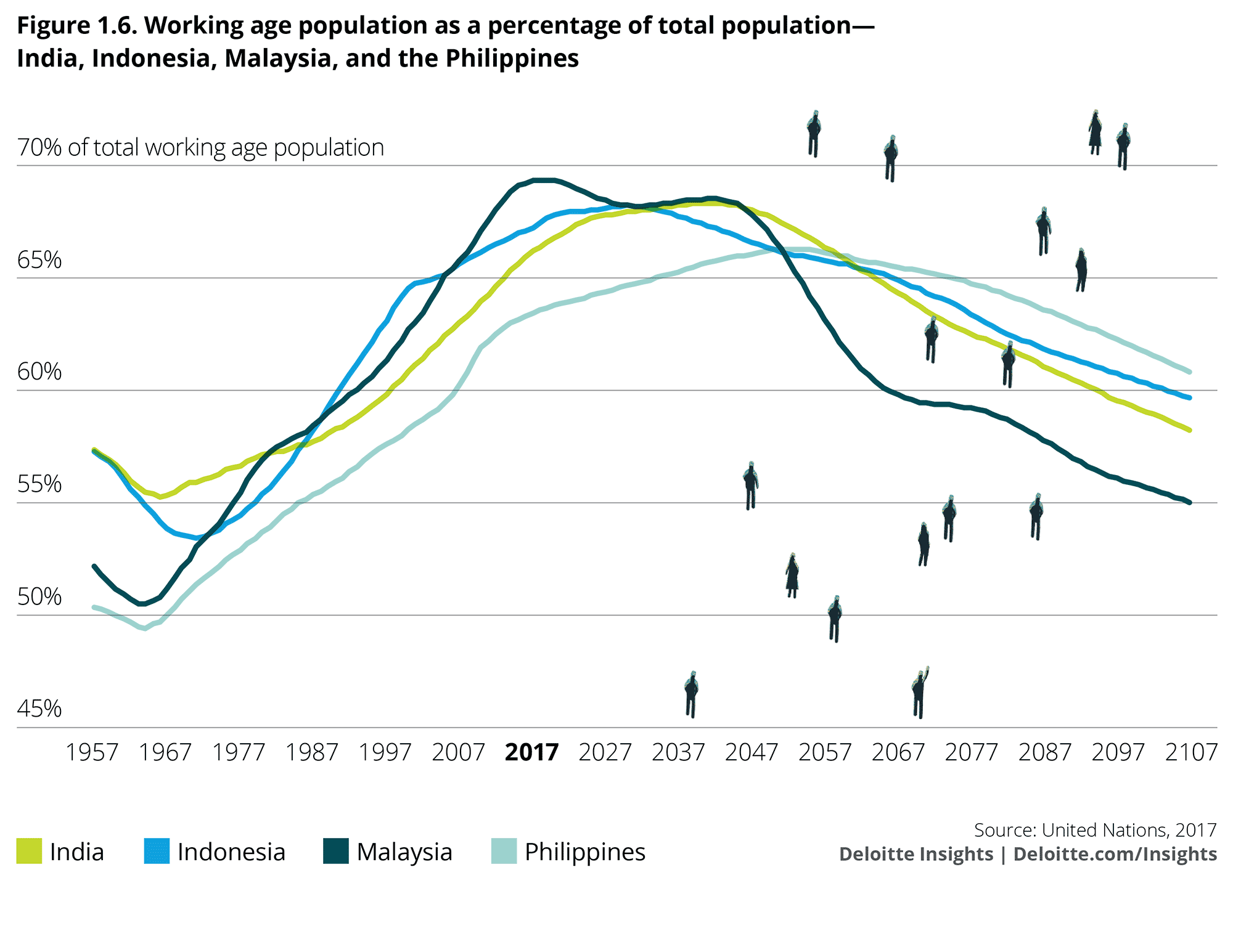

Yet, it is equally true that much of Asia’s story will also track India’s more positive outlook. That’s true, for example, of Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Although the lines in figure 1.6 map similar paths, the stories are slightly different.

As the most developed economy of this group, it makes sense that Malaysia is also the most advanced on its demographic journey. In 1965, barely one in two Malaysians were of working age. Now that ratio is at its peak—at close to 70 percent. Yet, unlike a number of nations, Malaysia’s demographic transition will be relatively gentle, and the impact of ageing won’t really take big bites out of its economic growth until the 2050s.

That decade, however, will see a demographic bell toll for Malaysia: Changed birth rates and a rise in life expectancy will see its demographics depart from the rest of this group, leaving it older and greyer than these others beyond that decade.

With a slower fall in its birth rate and an equally moderate advance in life expectancy, Indonesia will also see relatively benign demographic tides in coming decades. This is a nation with a younger population than many others, making demographics a tailwind rather than a headwind for growth through to the mid-2030s.

Thereafter, and in common with Malaysia, the transition from tailwind to headwind will also be relatively gentle—with the difference being that Indonesia’s glide path will remain gentle long after Malaysia’s doesn’t.

By the end of this century, Indonesia will have kept its status as younger than average, competing with the Philippines on that score.

An Indian summer set to last for half a century

Figure 1.1 showed three great growth waves through Asia, beginning in Japan, spreading to China, and increasingly encompassing India.

Yet the figure doesn’t pick up the absolute size of these waves. And those differences are tremendous.

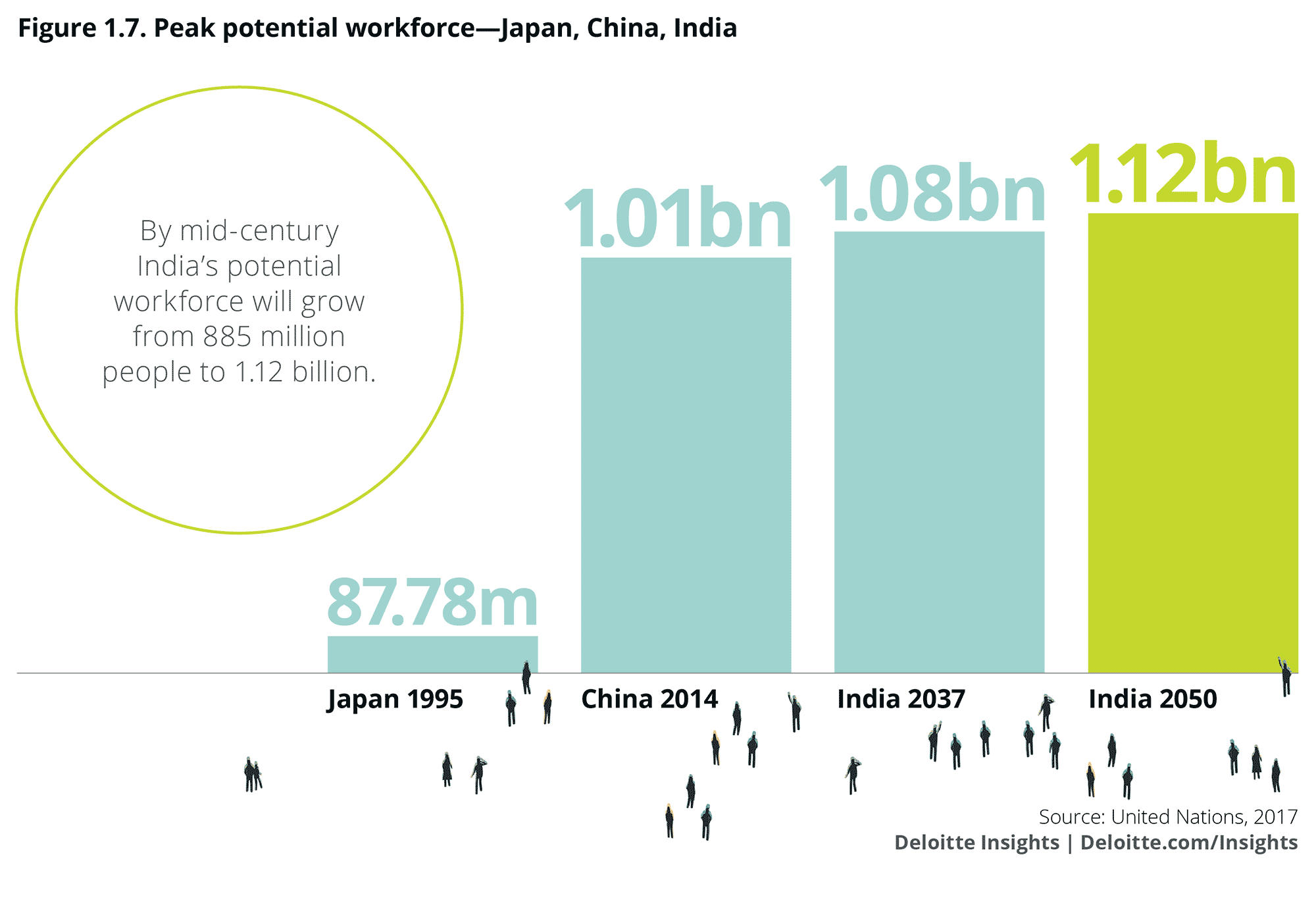

As we saw, Japan’s working age population peaked close to a quarter of a century ago, at less than 90 million potential workers. Figure 1.7 shows the peak in China’s workforce at more than ten times as many people—more than a billion potential workers—far and away the greatest workforce the world has ever seen.

China’s rise across recent decades indeed moved the world.

And there’s further potential there too. Although China’s demographic tides are moving fast, changes in the skills base of its workforce and the potential for a range of reforms to unlock assets into more productive use means that economic forecasters still rank China second with regard to expected speed of growth over the next decade.

The nation expected to beat China—the one that the consensus view of forecasters sees having an economy growing even faster than that of China over the next decade—is India.

That’s because the coming wave of people power will have an even higher crest.

India’s potential workforce today is 885 million people. Yet:

- As seen in figure 1.7, this number will jump to 1.08 billion people some two decades from today, and it will remain above a billion people for half a century.

- These new workers will be much better trained and educated than the existing Indian workforce, and there will be rising economic potential coming alongside that, thanks to an increased share of women in the workforce, as well as an increased ability and interest in working for longer.

This combination says the three big levers of economic potential—the 3Ps of population, participation, and productivity—are all set to surge in India.

The numbers here are simply staggering:

- Over the next decade, India’s working age population will rise by 115 million people and account for more than half of the 225 million expected across Asia as a whole.

- Across that same decade, Japan’s working age population will shrink by more than 5 million people, and China’s by 21 million.

- And the decade after that—through to the mid-2030s—will see India’s working age population jump by another 78 million people, but Japan’s will once again shrink by 7 million, and China’s demographic destiny will enter a sharper decline, with a further drop of more than 80 million.

The next 50 years will therefore be an Indian summer that redraws the face of global economic power.

However, there’s an important caveat—and opportunity—to note. “Getting richer” isn’t guaranteed. India needs the right institutional set-up to promote and sustain its growth. Otherwise its rising population could cause increasing unemployment and consequent social unrest—the phenomenon often observed in African countries.

In particular, it will be vital to get more women to join the labour market. Yet workforce participation by women in India has fallen rather than risen, dropping from 37 percent to 27 percent over the last decade.

India is not alone in seeing female participation rates fall over recent years; China, Indonesia, Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, and Japan have all seen either stable or falling rates since 2000. However, female participation in India is significantly below the rates in all these countries, meaning there is far greater economic potential that could be unlocked.

For India’s economic growth to outperform the potential mapped out in this article, women’s participation needs to start to rise from its current global ranking of 16th lowest in the world.7 This is a key issue we pick up in the second article in this issue: Asia’s growth on the cusp of change, driven by demographics.

As figure 1.1 illustrates, the Indian demographic cycle is about 10-30 years behind that of other countries. This presents an opportunity for it to catch up with its peers in per capita income levels. However, the Indian story has some unique features:

- First, India’s working age population to non-working age population is likely to peak at a ratio much lower than Brazil and China, both of which sustained a higher level for at least a quarter of a century.8

- Second, India is likely to remain close to its peak for much longer than other countries.

The growth consequence of such a phenomenon would come in the form of reduced fluctuations in growth compared to other East Asian countries. Both the acceleration and deceleration in growth momentum are likely to be slower, suggesting India’s demographic structure could sustain higher levels of growth for longer.

The next decade will see a changing of the guard

Asia’s growth momentum is on the cusp of significant change.

Two centuries ago, Napoléon Bonaparte noted “China is a sleeping giant . . . when she wakes, she will move the world.” He was right. But now, with demographic changes impacting the entire Asia Pacific region, there are stirrings and rumblings among many giants, which see a new terrain of challenges and opportunities emerging.

This article makes the point that the great underlying force of change—people power—has driven a series of surges in economic capacity across the Asia Pacific landscape. After the first wave, in Japan, the second wave of growth, seen in China over the past four decades, reshaped the world’s economy. Now, a third wave shows India moving front and centre stage. Its rise as an economic superpower is about to be felt in earnest, with further growth to be driven by the increasing importance of Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

But just as these economies have seen the incoming tide of a rapidly rising working age population, the path of demographic transition is not one of endless growth. Population ageing will see the growing impact of rising retirements across much of Asia, as the likes of China and Australia join Japan in seeing their economies grow more slowly due to the force of demographics.

In combination, those effects will rewrite the playbook of businesses around the globe. Both the levels and types of growth will bring new opportunities, risks and challenges. Population growth is often a cause for concern: The global population rising from 7.5 billion now to 10 billion by the middle of the century will bring many challenges.

And, in addition to the mere number of people, there will be changes in the way they want to live. As Asia’s growth on the cusp of change, driven by demographics notes, younger people across Asia often aspire to the lifestyles of their peers in the West, rather than their own parents.

That choice will drive increasing demands on the global environment—a fraught prospect. Yet it is also true that we have made incredible strides in lowering the inputs required to create the output we desire, an oft-forgotten trend that works against the more obvious increases in consumer spending.

But, these demographic trends are coming, whether we want them or not. This means we really have little choice but to face up to them head on, embracing the changing demands of the future (rather than pretending that, if we ignore them, they will go away).

The next article, Asia’s growth on the cusp of change, driven by demographics, looks at how various Asian economies and businesses are already preparing themselves for these coming changes. It also gives some concrete examples of how businesses can harness the opportunities that areas of stronger growth will provide, and be prepared for the challenges that ageing populations will bring.