Shifting gears into new mobility in Europe Overtaking old habits

10 minute read

19 December 2019

With a new pool of providers and a range of different options, what could persuade us to hand over the keys and step into the world of a new mobility?

It’s 2035 and Jennifer is commuting to work, as usual. She sits back in a plush seat in the autonomous roboshuttle, and greets a disabled passenger who has just been picked up from his doorstep. Checking her phone, she sees that the shuttle service has pinged her a suggestion: her calendar shows that she has a doctor’s appointment at 3 pm... Does she need a lift to that? She uses the app to decline, and to pre-pay for the bike that she will hire to ride to her appointment. Jennifer spends the remaining 20 minutes of her journey in comfortable silence, reflecting on the day ahead and glancing idly at the advertisements displayed on the shuttle’s screens.

Learn more

Explore the Future of Mobility collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

This scenario seems to be moving rapidly from science fiction to possibly reality in the not-too-distant future, thanks to new mobility,1 which is sparking interest among more than just car manufacturers.

New mobility is somewhat unique in the way it seems to invite the engagement of entrepreneurs, manufacturers and service providers from non-transportation sectors. We are witnessing the emergence of innovative offerings from organisations that are not traditionally linked to the world of mobility: insurance, energy, banking, technology and government entities among them. Taking on new roles, they can disrupt the mobility landscape and shape the future of how we move around urban environments.

Although wide scale deployment of new mobility services may not yet be possible outside populated areas, in big cities and their surrounding neighbourhoods, a new mobility paradigm appears to be emerging. It is expected to come from changes in consumer behaviour and perceptions, and from technological innovations in autonomous driving, electrification, connectivity and shared mobility.

This evolving field is rich with opportunities, but also rife with challenges for both public authorities and private businesses: a crucial step these stakeholders can take at this moment is to listen closely to the views of the public. The most brilliant mobility solution will likely fall flat if it does not have general appeal.

Deloitte conducted field research in Europe to find out how willing those surveyed are to change their habits, and what it would take to bring real transformation. The views of the respondents point to the need to incentivise people in two ways, through public initiatives and private offerings. Only with commitment in these areas – from city administration officers/planners, the automotive sector, insurance companies and other service providers – would individuals likely become more willing to adopt new modes of transport. The goal of the industry is for people to wake up one day and realise that there’s a better way to get around ... a way that is simpler, cheaper, more environmentally sustainable, and more appealing than the one they chose yesterday.

ABOUT THE RESEARCH

Deloitte’s research is based on a study, conducted in collaboration with external research agency SWG, aimed at investigating perceptions among European citizens of the ongoing transformation of the urban mobility sector. Research focused on the main changes in individuals’ attitudes and behaviours, with analysis of the most significant trends and their disruptive effects on the mobility market.

Specifically, 1,568 interviews were collected in Italy and 2,072 in four other countries: France (504), Germany (505), the United Kingdom (503) and Finland (560). The first four countries were chosen for being the most populated EU countries; Finland was chosen as an example of best practices in new mobility, resulting in an outlier for some topics.

The interviews were conducted online via the computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) methodology, between 15 and 29 May 2019. Results were weighted to represent the population in terms of age, sex, geographical distribution and city size.

New problems, new approaches

The age-old puzzle of how to get from here to there has spawned some of humanity’s most inventive thinking, especially in terms of urban planning. Today we face unprecedented migration of people into cities, and traditional solutions are often no longer sufficient given increasing congestion, pollution and strain on existing resources. New problems have led to new approaches of transportation.2

To a certain degree, the future of mobility also depends on Mobility-as-a-Service, or MaaS. This holistic concept is already being tested in Helsinki, Paris, Los Angeles and Singapore. MaaS merges data from different sources and connects stakeholders to offer a seamless transition from one mode of transport to another. The MaaS-enabled traveller has the freedom to choose whichever mode offers greater convenience and results in a journey that satisfies his or her priorities (for speed, price, etc).3

To realise such a liberating vision, we likely also need integrated, smart digital platforms that empower users to tailor their journey and book door-to-door trips with a single app, rather than locating, booking and paying for each mode of transport separately.4 Such a platform could be made possible by a comprehensive, integrated mobility operating system (mOS) that combines physical infrastructure, modes of transportation and transportation service providers.

By blending Internet of Things technology, big data and cognitive analytics, a mOS can better balance supply and demand, and enable urban dwellers to reap the benefits of efficient transportation resources.5 With this kind of system,6 new mobility stakeholders would have an opportunity to address the mounting concerns about congestion and pollution.

MaaS is only in its early stages of development,7 however, MaaS solutions have the capability to create real lifestyle changes. Picture a city that lets you move around with ease, so that you would want to cast aside your old travel habits along with your car keys.

Mobility as an everyday priority

Who would be the architects of this brave new world: the private sector, with companies that stand to benefit financially; or the public sector, with institutions crafting policies that support new solutions? Both have important roles to play. If they work in tandem, we might all benefit: a reduction in congestion would be expected to result in higher productivity, better air quality, fewer traffic accidents and less need for urban parking space.8 For individuals living outside major cities, resolving issues such as parking and congestion may not have a major impact on their lives, but Deloitte’s research shows that many people have real concerns stemming from their mobility choices – or lack of them.

Fifty-three per cent of the individuals interviewed by Deloitte perceive mobility as a daily concern. This is particularly true for those in the millennial age range (63 per cent) and those living in large cities/capitals (Paris: 75 per cent, Rome: 70 per cent, Berlin: 59 per cent, London: 54 per cent) – although, according to Deloitte’s annual City Mobility Index, these cities are well positioned to support new mobility services.9

For 45 per cent of interviewees, mobility has a negative effect on their quality of life, by influencing how they spend their free time (67 per cent), by representing a significant cost (67 per cent), and through limiting family choices (58 per cent). These individuals may be mainly city-dwellers, but their concerns are worthy of consideration – the number of town and city dwellers is expected to grow to 66 per cent of the world’s population by the year 2050.10

Interviewees expressed concern about the technology of mobility solutions. Sixty-three per cent think that the quality of vehicles (safety and performance) has improved, but they do not see any improvement in public transport services (punctuality, urban area coverage and environmental impact).

Fifty-four per cent of those interviewed expressed dissatisfaction with the private and public infrastructure that supports mobility – such as parking spaces dedicated to shared vehicles, charging stations for electric cars and bicycle lanes.

There are also concerns about the broader environmental effects of mobility. Sixty-two per cent of interviewees believe that vehicles and other means of transportation are the main cause of environmental pollution. This perception may reflect some bias or misconception, as pollution also has other causes; but the important lesson is that mobility is seen as a key factor for environmental sustainability. Seventy-three per cent of interviewees hold this view, which seems a good reason for regulators to prioritise it.

Sixty-seven per cent of interviewees may consider changing their current vehicle to a more environment-friendly one. However, this trend is being hindered by lack of affordability: forty-eight per cent of interviewees say they would not buy ecologically-friendly vehicles because of their current high price.

Sustainability measures by the government may also seem exceptionally slow, but changes are happening in many places. London recently created a tax break to encourage switching company cars to electric vehicles,11 and by 2020 all of the city’s bus fleet is expected to comprise either ultra-low-emission or fully zero-emission vehicles.12

Transportation habits and the path to new mobility

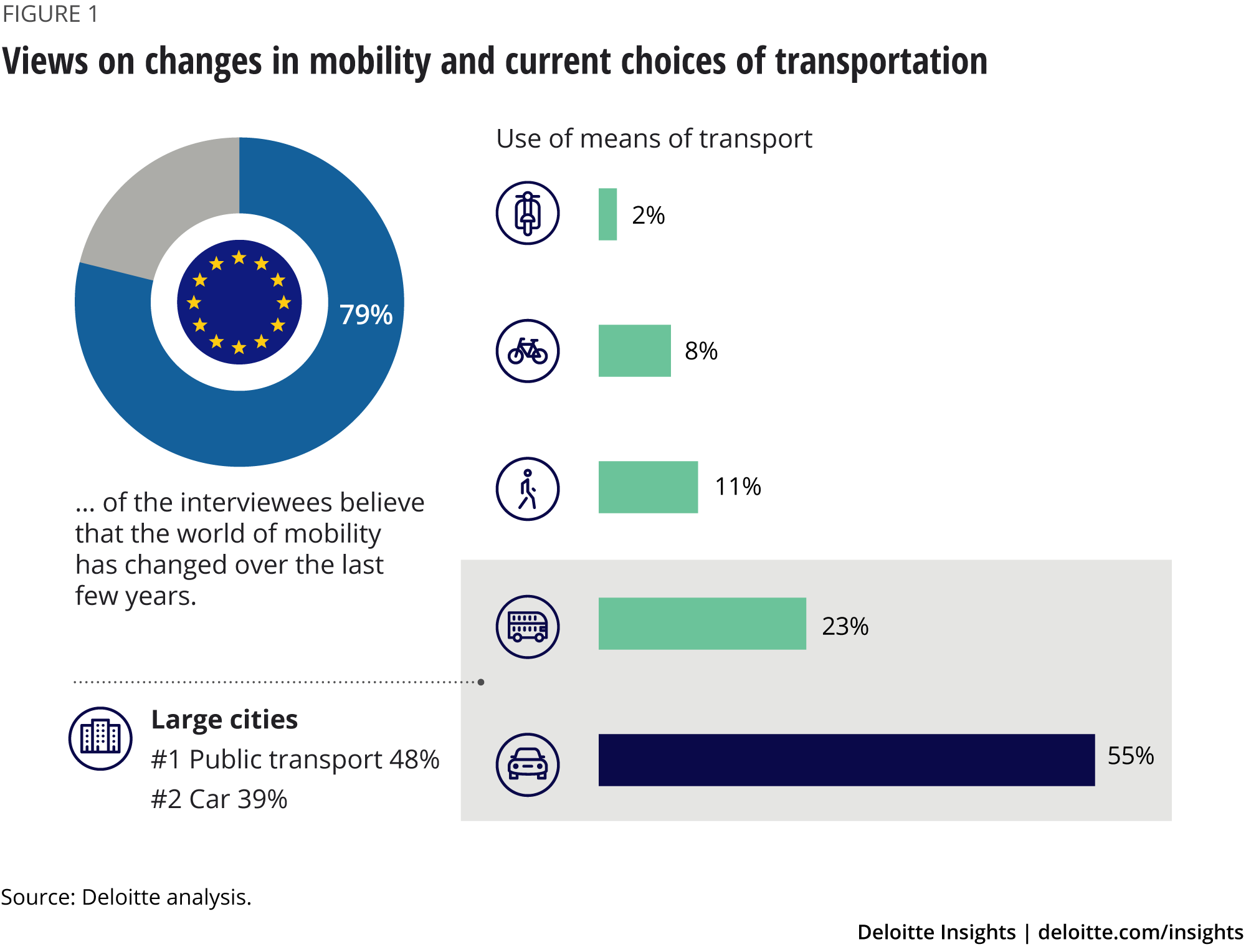

About eight in ten interviewees believe that the world of mobility has changed over the past few years. Many have been slow to adopt new mobility options themselves, but the pace of transformation could accelerate along with technological development and government initiatives.

Individuals are at least becoming aware of some of the advances in technology and mobility services that have occurred. On average, one half of interviewees think that the range of alternatives to car ownership has improved. But to what extent are they engaging in this new world of options? Based on Deloitte’s research, personal decisions about mobility seem to be largely based on issues of cost and convenience.

Figure 1 shows that, despite awareness of the changes in mobility choices, most interviewees are still using traditional ways of travelling around. In general, private cars remain the most popular option (55 per cent of interviewees). Even in large cities, 39 per cent of respondents still prefer their cars over public transport. In fact, the number of passenger cars in almost all EU member states has increased over the past five years, and passenger cars powered by alternative fuels (including hybrids) currently account for only a small proportion of all newly registered cars.13

Radical change may be a long way off; however, there are encouraging signs: forty-five per cent of interviewees said they would be willing to use new alternative forms of mobility in the next three years, if available in their city, although 67 per cent said the new forms would complement their private vehicles, not replace them.

The new model of the sharing economy

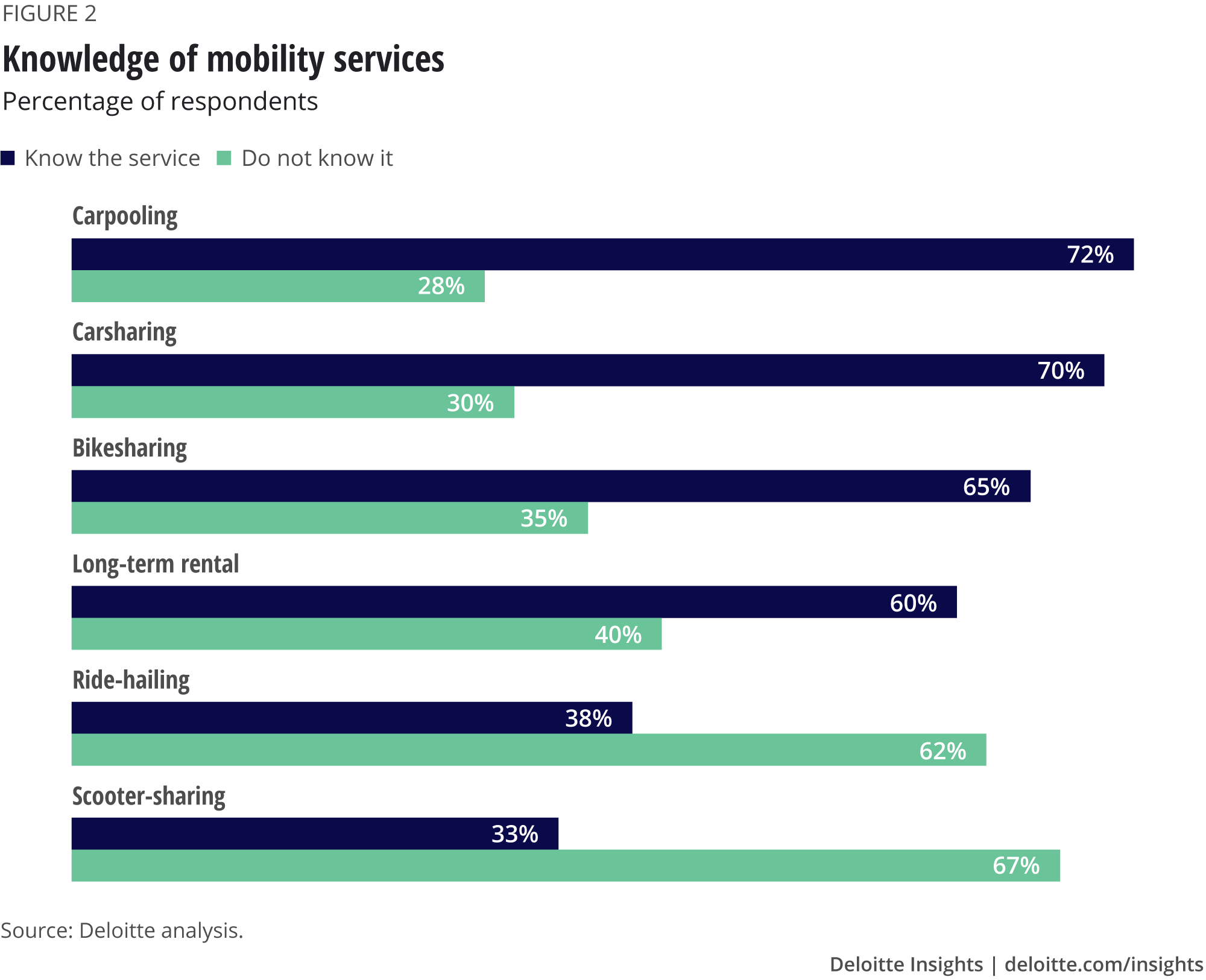

It is useful to shine a spotlight on shared-mobility options, which can bring private and public benefits without severing the bond between humans and their car. Shared mobility is gaining traction in urban centres and other areas of high population. But despite the attention these services have received, their use has not extended beyond a small niche of regular customers (figure 2).

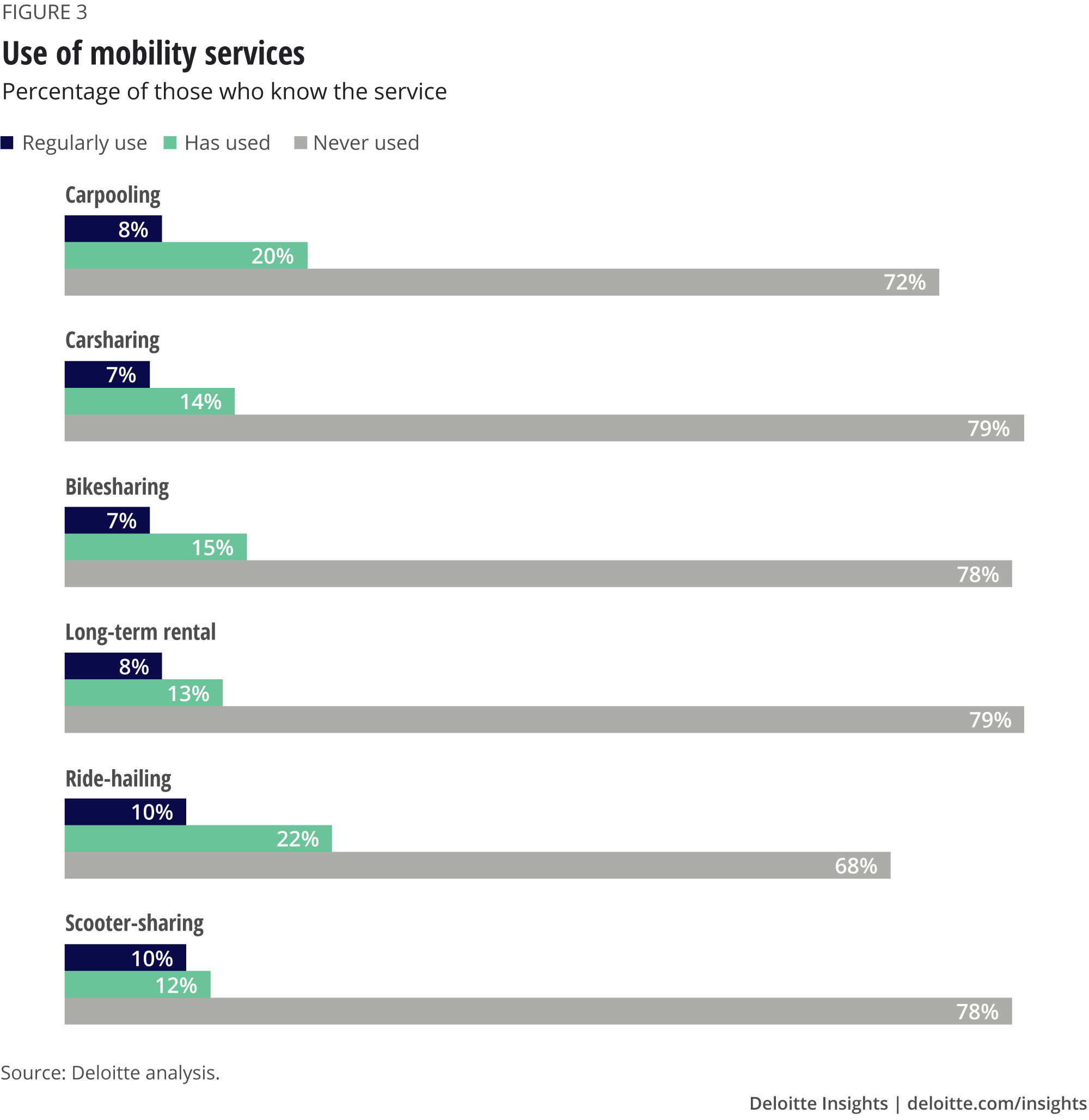

Although approximately seven out of ten interviewees are aware of carpooling and carsharing services, less than 10 per cent of them are regularly using them (figure 3). Fifty per cent of interviewees say that they do not consider the private or public infrastructure adequate for their mobility needs.

Interviewees indicate that there are several areas they believe should be improved in shared mobility services. They rank the factors that are causing them to resist new mobility options in order of importance, as follows:

1. limited convenience and flexibility of the services

2. price too expensive

3. lack of brand awareness of the specific service providers

4. complexity of use

SNAPSHOT OF GERMANY’S DRIVERLESS FUTURE

In September 2019 Deloitte examined the anticipated effects of a future with autonomous mobility services (robotaxis/ shuttles) in Germany.14 Researchers noted that private cars in Germany are actually used less than 5 per cent of the day, and occupy a parking space the rest of the time. This increases the costs and diminishes the appeal of owning a car, particularly for city dwellers. The fares for riding in self-driving vehicles are expected to be much lower than the costs of private car use. Moreover, the market potential for autonomous mobility services is staggering – representing an estimated annual sales volume of €16.7 billion by the time of expected widespread adoption in 2035. This amounts to almost one-sixth of current annual car sales in Germany.

Forward drive: Factors for new mobility success

Four areas of concern among interviewees about new mobility services can be expressed as: affordability; ease of access; understanding; and awareness. These may present a challenge for many service providers and regulators, but each can be surmountable in an ideal future.

Affordability

Eight out of ten interviewees cite price as the most important element in their journey-making decisions and 49 per cent say they would be willing to share their data to get discounts on mobility services. Thus, if pricing strategies can be redefined – for instance, by tailoring price discounts to a customer’s use of mobility services – and can be clearly communicated to the public, the incentive to change could be that much stronger.

Ease of access

Seven out of ten interviewees say they consider ease of access to services as essential, and 61 per cent believe it is important to have a single access point that integrates different services. This is where cities can find a solution through technology, such as mOS platforms. It’s hard to deny the appeal of using a smartphone app/account that seamlessly integrates services with a user-friendly interface and can be used for multiple forms of travel.

Forty per cent of interviewees say they are interested in purchasing an ‘all-in-one’ package that is valid for different forms of mobility. This may be considered the ultimate goal of giving customers access to a frictionless mobility experience.

Understanding

Marketing is not making citizens sufficiently aware of the benefits of shared mobility. For example, over 60 per cent of interviewees say they are not aware of some important benefits of carsharing, such as pay-per-use rates or free parking; and the further benefits of free access to limited-traffic zones, and merit-free insurance are not reaching all the target audience.

What’s more, seven out of ten interviewees are unclear about the offerings of even the most popular service providers. Marketing communications should be much clearer and more well-defined, seeking to make new mobility services the first choice option that comes to mind when planning a journey.

Awareness

New operators in this arena – such as insurance, banking, energy and technology providers – are failing to capture the market potential fully. Six out of ten interviewees are unaware of mobility offerings from providers that are not linked traditionally to the transportation sector. The upside is that 71 per cent of respondents are willing to buy services from ‘nontraditional’ operators (insurance: 67 per cent; energy: 66 per cent; tech: 65 per cent; banking: 55 per cent) (figure 4). Marketing and communication do not seem to be achieving their objectives in this regard.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that new mobility offers almost unlimited opportunities for private companies and public bodies, and unprecedented benefits for individuals. But a large proportion of the public seems either unaware of the offerings that are available, or is dissatisfied with services – factors that may only add to their daily struggle to get around. People could be willing to share journeys and give up personal details if it means a convenient and affordable daily commute. But many are also concerned about the environment and sustainability. Deloitte’s research highlights a fault line between what people want and the appeal and convenience of new mobility. It could be up to the public and private sectors to close the gap.

Public institutions are a driving force of new mobility, particularly those with a holistic approach that are willing to work in cooperation with all other interested parties. Fundamentally, their objective should be to treat mobility as a system of systems and be wary of creating unforeseen problems or making existing problems worse (for example, by increasing traffic congestion or causing gridlock).

Public initiatives can be pursued to:

- develop an innovative infrastructure that would encourage the use of new services, with country-specific considerations;

- update the legislative framework to address the uncertainties generated by new mobility and favour the adoption of different services;

- support new private companies – either startups or established organizations – in developing and marketing new mobility services.

In the private sector, service providers stand to potentially reap great rewards, if regulation permits. They can tap into the needs of individuals and pursue strategies and initiatives that can:

- redefine the value chain of new mobility, starting with an enhancement of the current position, and then defining the most appropriate methods of further development, upstream and downstream, in terms of services and possible partnerships;

- simplify and evolve the customer experience, for example, by exploiting new technologies to aggregate various forms of mobility or introduce all-in-one mobility packages;

- expand the range of offerings by introducing ancillary services not limited to mobility, such as allowing a customer to book and pay for parking through an app;

- communicate targeted and clear messages, highlighting the value proposition and making it easily understandable, for instance, through social media channels, and encouraging information exchange between users and non-users. Examples include campaigns such as “invite a friend and get a reward”;

- customise pricing models that adapt dynamically to customers’ individual profiles, by monitoring their history, methods of travel and driving style.

Why should people move out of their comfort zone when it’s not clear what there is to gain? Perceptions must be transformed before habits change. But with new operators from non-transportation sectors taking turns behind the wheel, it is not impossible to imagine a utopian future where individuals move willingly out of the driver’s seat, to the benefit of us all.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Discover more on new forms of mobility

-

Toward a mobility operating system Article5 years ago

-

The elevated future of mobility Article5 years ago

-

Making the future of mobility Article7 years ago

-

Elevating the future of mobility Article7 years ago

-

Picturing how advanced technologies are reshaping mobility Article6 years ago