The talent paradox Technically advanced, intuitively limited

10 October 2018

Our survey revealed an interesting talent paradox: How can organizations state that they have the exact workforce skill sets in place, yet finding and training the right talent is also their top challenge?

In an age of digital transformation, it probably comes as a little surprise that individuals are constantly challenged to evolve or, at minimum, keep pace with the technologies their organizations look to implement. Sloan Management Review and Deloitte’s 2018 Digital Business Global Executive Study and Research Project reinforces this sentiment, as 90 percent of those surveyed see the need to update their skills at least annually—of which half see development as a year-round, continuous exercise.1

Learn More

Explore the Industry 4.0 Paradox report:

Around the physical-digital-physical loop

View the entire Industry 4.0 collection

Subscribe to receive updates on Industry 4.0

Operating in this “development-focused” climate makes our first talent finding so surprising: Of the 361 respondents, 85 percent are more likely to agree that their organization has “exactly the workforce and skillset it needs to support digital transformation.” Yet, when we dig a bit deeper and ask participants what operational and cultural challenges are most commonly faced by their organizations, finding, training, and retaining the right talent is cited as the number one challenge (by 35 percent of respondents).2

Juxtaposing these responses presents an interesting paradox. How can individuals overwhelmingly state they have the exact workforce and skillsets in place but simultaneously recognize that finding and training the right talent as their number one challenge?

The answer may lie in the perceived accessibility to these digital technologies: How individuals view their personal interactions and ability to navigate these technologies carries significant weight in their organizational talent assessments. Whether differentiating between “power users” and novices or comparing high ROI organizations with the rest of the field, the perceived accessibility of these technologies seems to continually influence talent perceptions.

The perceived accessibility of digital technologies seems to continually influence talent perceptions

Extending the reach of the “power user”

In the mid-1970s, the personal computer (PC) was reserved for hobbyists who enjoyed the technical nuances of hardware and coding. This was a technically savvy, niche group of enthusiasts. When computers began to feature more intuitive graphical user interfaces (GUI), the PC became a bit more personable.3 From small businesses to classrooms, adoption skyrocketed.

The story of today’s digital technologies may parallel the early journey of the computer. In our analysis, we isolated talent views by self-perceived interaction with these digital technologies (figure 1). The results revealed, quite drastically, that the more respondents use these technologies, the more likely they are to be satisfied with their organization’s current state of talent. At its most polarizing, those who interact with these technologies on a daily basis (indicated by a “5” in figure 1) believe their organization has the proper talent in place 92 percent of the time, while those who have little to no interaction with digital technology (a “1” or “2” in figure 1) see the greatest gap in talent and development (only 43 percent believe the right talent is currently in place).4

The more respondents use digital technologies, the more likely they are to be satisfied with their organization’s current state of talent.

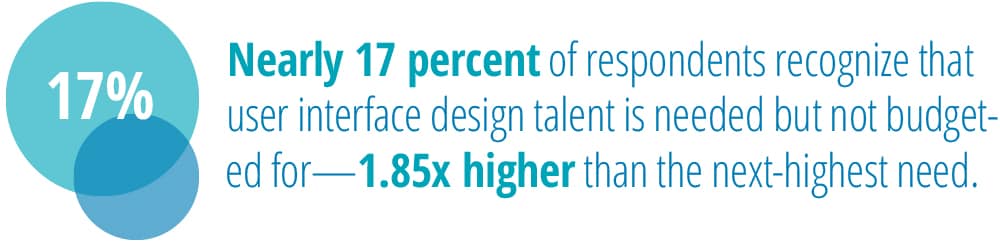

Through their own engagement with the technology, executives may perceive these technologies as something “regular people” can handle and implement on their own—perhaps with a little help from a more intuitive design. We see this manifest when assessing the greatest talent needs within the organization. When asking respondents where talent is required the most, overwhelmingly, people point to user interface design. Specifically, almost 17 percent of respondents recognize that user interface design talent is needed but not budgeted for (1.85 times higher than the next-highest need, machine-level controllers). In fact, only a third of respondents believe their organization is already equipped with enough user interface design talent. This is comparatively lower than the other three forms of talent: data science, software development, and machine-level controllers, where respondents indicated they have enough talent on hand, at minimum, 46 percent of the time.

Beyond talent, it appears that individuals yearn for more accessible technology investments as well. For instance, in our discussion in The innovation paradox, we see that many of the respondents are increasingly looking to invest in data visualization technologies and big data platforms—that is, digital technologies that make comprehending and acting upon insights easier. Coupled with the emphasis on user design talent, we see a relatively clear shift toward technology usability as an area of focus. Research shows that technology implementations fail rarely because the technology did not work but rather because people are not willing, or find it too difficult, to use them.5 Thus, organizations could offer digitally transformative capabilities across a broader swath of their operations—and ensure people will be able, and willing, to use them.

It takes talent to sustain success

Conventional thinking might suggest that the more successful organizations have been at implementing digital technologies, the more likely they are to have the right talent in place. However, when we assess organizations that have achieved significant ROI through digital transformation against the rest of the field, we observe that talent concerns seem to rise with success (table 1).

If higher ROI signals greater digital transformation maturity, the next evolution could be accessibility for the user. In fact, a growing body of literature suggests that better, more intuitive design is the “last mile” to unlocking these capabilities.6 Consider Deloitte’s 2018 The Fourth Industrial Revolution is here—are you ready?, where executives indicated that they mostly apply these technologies for operational goals, but that building an Industry 4.0 society—and ensuing workforce—requires a broader approach that facilitates better, more user-friendly collaboration between humans and machines.7

These high-ROI organizations may see talent as the means to both sustain and elevate their digital technologies to new levels of sophistication. As during the formative years of the PC, better design can unlock the technical capabilities already in place. Recently, GE has placed a premium on design as products such as jet engines and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines are now part of digital ecosystems, and ease of assimilation and usage are paramount to successful adoption.8

A clearer talent picture

Indeed, the ever-present need for better, more skilled talent isn’t going away. Instead, the increased appetite for digital technologies is fueling a demand for greater accessibility to these capabilities throughout the organization.

There is good news: Executives can help unlock these digital capabilities by collaborating directly with front-line leadership. In discussing your digital technology needs, consider these three facets of talent:

- Build these capabilities with, not for your employees. These technologies tend to work best when they are built collaboratively with their business users rather than for them.9 Employees that are not fully immersed in the digital integration process may react with a level of skepticism (or confusion) to its benefits.

- Hire for design. Better user interface design can act as the channel to greater employee engagement with these digital technologies. Further, the more intuitive the design, typically the less need for finding new talent with greater technical skills. This is especially important as many of our respondents indicated that user design talent is an unbudgeted need.

- Sustaining success requires continual investment in talent development. If accessibility is the linchpin to adoption, leaders may need to continually ensure that their people have the right tools in place to use and interact with these enhanced features. Encouragingly, these trends in accessibility and design suggest that organizations may be better suited in investing in training and talent that make these technologies more engaging rather than opting for a wholesale change in personnel and skill sets. These upfront investments can extend the reach of these technologies throughout the organization—in a more sustainable manner.

With a focus on accessibility, organizations can better use and upskill their existing employee talent to interact with and unlock the full capabilities of Industry 4.0 technologies.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.