Breaking constraints: Can incentives change consumer health choices? has been saved

Breaking constraints: Can incentives change consumer health choices? Part of a Deloitte series on innovation

22 March 2013

- Paul H. Keckley

Innovative incentive programs may well help individuals overcome the inertia that limits engagement in wellness programs, disrupting the trade-offs people make when pursuing health care goals.

Consumer incentives: Is now the time?

There is widespread agreement that unhealthy behavior is costly to employers, publicly funded health care programs, and families. What’s not clear is how to change those behaviors and at what cost. In many ways, the US health system has been hamstrung by its inability to know how best to change, reduce, or eliminate the unhealthy behaviors of its citizenry—it’s a major dilemma for employers.

An example (some HR executives may be familiar with the data): Each smoker costs a company an additional $3,856 in medical costs and lost productivity annually.1 The company is planning a smoking-cessation program, but results have historically been modest, with few managing to stop permanently.2 But might incentives increase the success rate? If so, what types and how much? What’s more, the lack of consistency around which types of incentives work best, if at all, may constrain action: The HR department is hard pressed to recommend a solution that’s widely supported by objective data.

Why is this important? Employee ill-health is expensive.

Many employers are actively trying to manage health care costs by encouraging employees to take steps to maintain or improve their health. Worksite wellness programs are a convenient vehicle for employers to support wellness efforts, covering things from health promotion and preventive screenings to specific programs for workers who already have a medical condition. Some variant of workplace wellness programs can be found in over 90 percent of US companies with 200 or more workers that provide health benefits.3 In 2011, investment in health improvement programs was estimated at around 2 percent of companies’ medical spend.4

But can employers persuade workers, whose customary lifestyles may include a lifetime of bad habits, to be less “couch potato” and more “self-starter”—and exercise more, eat healthier, and stop smoking? Many are turning to using incentives to target such things as immunizations, annual screenings, and medication compliance to provide the extra nudge that some need to bridge the gap between good intentions and decisive action in managing their health. Even a once-healthy person, when diagnosed with a chronic condition, may choose to become non-compliant with their medication and treatment almost 50 percent of the time.5

So how effective is the use of incentives to engage employees in employer-sponsored worksite wellness programs? While a great variety of incentive types (such as cash, cash equivalents, and cost sharing) and approaches to incentive program design are being experimented with, it is not clear if incentives improve health or just add costs. Based upon a review of the literature, this report weighs the available evidence on the use of incentives and their potential to drive employees’ participation and achievements in health management programs.

The impact and effectiveness of using incentives is not well understood. What’s widely assumed is that they work; what’s unclear is what types of incentives produce the targeted return. Incentives are a link between the present state and what employers hope to achieve. Can incentives become a lever by which the status quo is disrupted and new possibilities emerge?

Even though the use of incentives is widespread, the frontiers of incentives remain largely unexplored. Conceived and executed in innovative ways, incentives hold the potential to “move the needle” in shaping consumer behavior in such diverse areas as chronic health management, prescription medication compliance, uptake of generic alternatives, and achievement of personal milestones—and to underpin self-directed care as health care transforms into a more efficient, patient-centered system of care.

As employers jockey to secure a competitive and productive workforce and gear up for the 2014 changes in their health benefits obligations arising from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, assessing the role that incentives might play in leading individuals to make different choices will be part of their deliberations. Provisions in the ACA greatly enhance employers’ ability to reward their employees with incentives. The opportunity has never been greater for employers, health plans, and incentive management vendors to explore creative ways of taking advantage of the provisions and drive new, innovative programs that could reduce costs associated with individuals’ lifestyle and compliance choices.

Perhaps the timing is right to break worksite constraints around wellness programs for employees. Pairing incentive strategies with rapidly developing digital technologies such as mHealth holds the potential to drive fundamental changes to the wellness paradigm. So do approaches such as using gamification in health care and changing the financial relationships between individuals and their providers. Incentives may well play a considerable role in migrating employees to the next generation of worksite wellness programs, thus breaking out of a “one size fits all” presumption that has shown mixed results and garnered skepticism in many C-suites.

Incentives are a link between the present state and what employers hope to achieve.

Background: The experiences, the constraints

Not all employers are pursuing worksite wellness. But many larger companies are making considerable investments in health management programs to address their employee population’s health and rein in growing health care costs. The results are all over the place.

Despite the fact that around 6 in 10 employers in one survey either don’t know or don’t measure the return on investment (ROI) of worksite wellness programs,6 the number investing in such programs is steadily rising7—reflecting expectations that benefits will exceed program costs. Workplace health promotion, illness prevention, and disease management programs have been shown to be effective in modifying health risk—at least in the short term. But the big challenge for employers is to sufficiently motivate employees to participate. Data suggests that only around 20 percent of a company’s eligible population may become involved in company-sponsored programs.8 Many employers identify the lack of employee engagement and low participation levels as being their greatest challenge in managing health care costs.9 Some employers have turned to using incentives, in particular financial incentives, as a tactic to drive participation in worksite wellness programs and to ultimately engage employees.

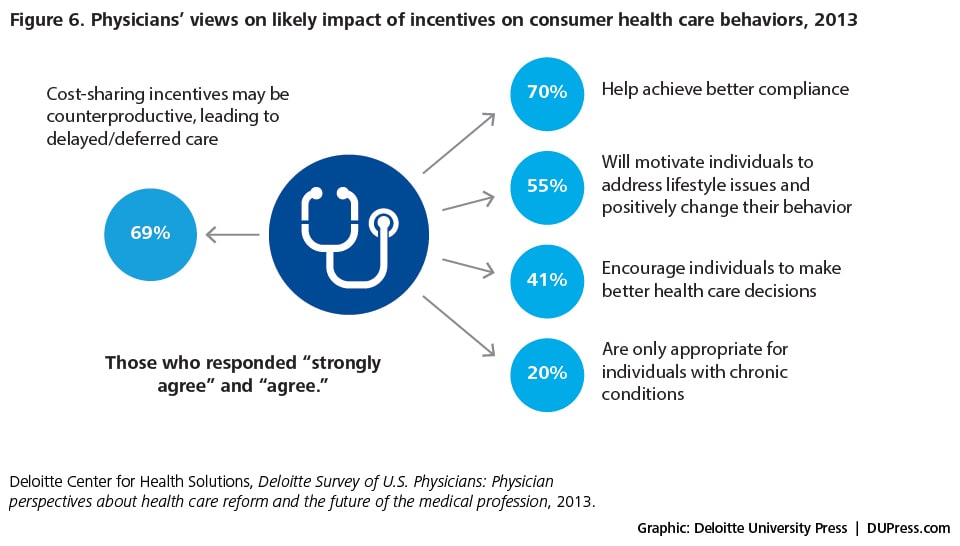

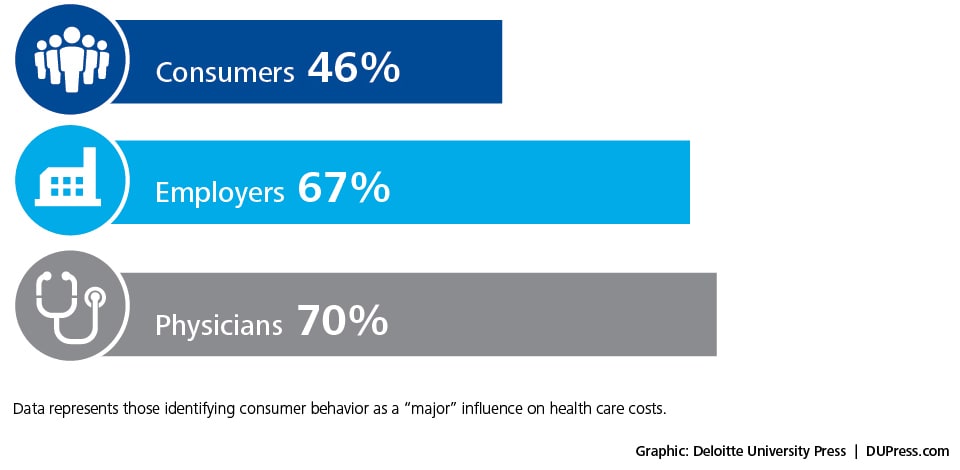

In three recent nationally representative studies conducted by Deloitte, 70 percent of physicians surveyed and 67 percent of employers surveyed considered that consumer behavior (such as unhealthy lifestyles that contribute to obesity) has a major influence on overall health care system costs. On the other hand, slightly fewer than half of consumer respondents (46 percent) believed this to be the case.10

In three recent nationally representative studies conducted by Deloitte, 70 percent of physicians surveyed and 67 percent of employers surveyed considered that consumer behavior (such as unhealthy lifestyles that contribute to obesity) has a major influence on overall health care system costs. On the other hand, slightly fewer than half of consumer respondents (46 percent) believed this to be the case.10

Only around 20 percent of a company’s eligible population may become involved in company-sponsored programs.

Constraint one: The cost of health care

As employers seek to manage the growth of health care costs and pursue high-value outcomes for their investment, being able to predict likely health care expenditures and to make informed decisions about where to invest scarce resources may unlock considerable value. Managing or reducing common and costly risk factors through worksite wellness programs and incentives to help employees make healthy lifestyle choices is growing in popularity.11 And while experts debate the cost-effectiveness of regular screening programs, such programs, if carefully chosen, are considered to be cost-effective and potentially cost-saving.12 Chronic disease accounts for 75 percent of annual national health care expenditures13 and causes 70 percent of all US deaths.14 Diet, activity patterns, and tobacco and alcohol use have been associated with a “substantial proportion of preventable deaths,”15 and consumer behavior and lifestyle factors directly contribute to modifiable health risks that can lead to illness, morbidity, and mortality. Despite this, since 2001, only 3.5 percent ($88.4 billion) of the total annual US health care spend has been directed toward the promotion of healthy behavior and illness prevention.16

According to one study representative of the national population, around 86 percent of the full-time US working population has at least one chronic disease or is overweight.17 Employers’ impulse to keep their workforce healthy through prevention and wellness programs is understandable—health-related productivity loss is a major concern for employers, who not only pick up the majority of the cost of purchasing insurance coverage but also deal with the fallout of ill health, including medical and pharmaceutical costs, absenteeism, presenteeism, and short- and long-term disability claims.18 An average of $2.30 in health-related productivity costs is borne by employers for every dollar spent on worker medical or pharmacy costs. Chronic conditions such as depression and anxiety, obesity, arthritis, and back and neck pain are the major causes of productivity loss.19

Cost constraints are always central to an employer’s view about health care. A view of wellness as an investment, accompanied by a methodology that is widely used in industry with a measurable ROI, is a constraint that restricts the unexplored possibilities of such programs.

Constraint two: The role of wellness programs in recruiting and keeping talent

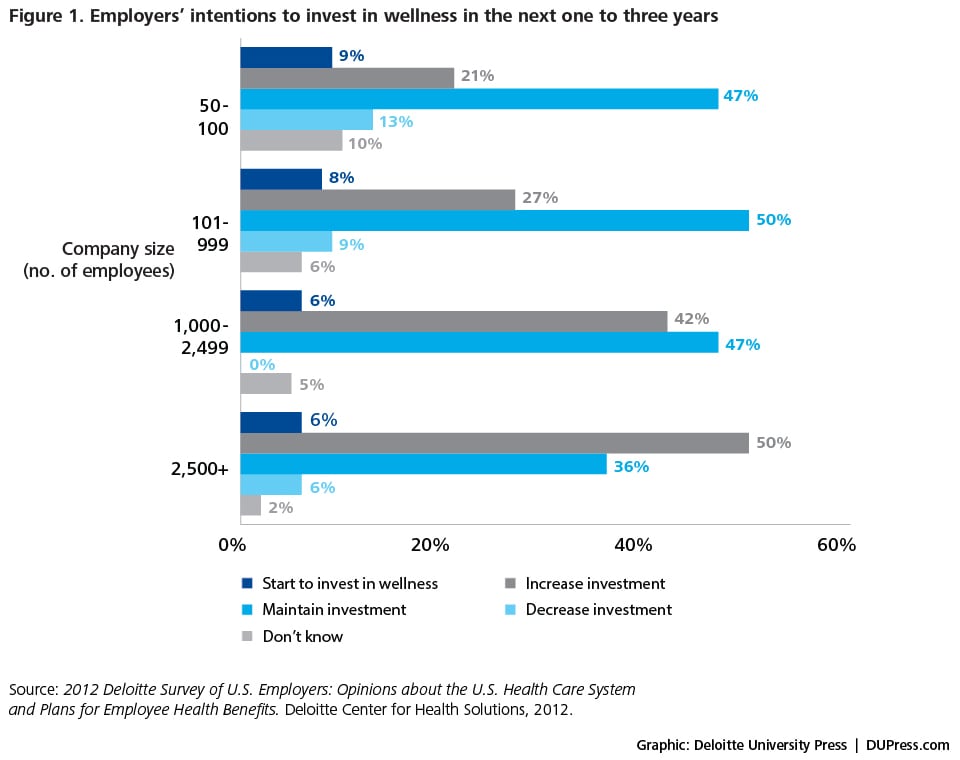

Eight in 10 employers surveyed say they are committed to providing health benefits to retain and attract talent and improve job satisfaction.20 In a 2012 study examining employers’ predisposition toward benefits strategies, Deloitte found that the majority of respondents anticipated maintaining health benefits for their employees but foresaw changes to their programs. Most did not plan to drop employee coverage; rather, they anticipated using defined contribution plans to shift more accountability to employees for cost control and quality. Most employers in the survey intended to change their benefits strategies in the next three to five years by increasing employee cost-sharing (69 percent) and the use of preventive health programs (62 percent). When asked if they anticipated investing further in wellness programs or otherwise, half (50 percent) of the large employers (2,500+ employees) in the survey planned to increase their investment in health and wellness programs in the next one to three years (figure 1).21 The constraint here is value: the intrinsic impact of wellness programs on employee morale, presenteeism, and productivity, and the success of the organization’s recruitment and retention efforts directly attributable to wellness program investments. How value is measured on the people side of the enterprise is a constraint that forces every employer to second-guess the role, scope, and likely impact of wellness benefits.

Constraint three: Regulation

The ACA of 2010 places emphasis on prevention, endorsing preventive and wellness services as one of the 10 essential health benefits that must be covered by health plans operating through a health insurance exchange.22 The ACA outlines a central role for employers in offering incentives to promote wellness and greatly expands employers’ ability to reward their employees with incentives. The ACA increases the maximum permissible reward (which can be an adjustment to premiums, copayments, or deductibles) from 20 percent to 30 percent of the total cost of coverage—and potentially up to 50 percent for smoking-cessation incentives—beginning in January 2014 (see sidebar, “Facilitating a focus on workplace wellness”).

Facilitating a focus on workplace wellness

The ACA of 2010 builds upon existing wellness concepts first outlined in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) Act of 1996 and expands the use of incentives to further encourage well-designed and non-discriminatory health and wellness programs in the workplace.

Two types of wellness programs are endorsed in the ACA: participatory wellness programs, which are non-conditional, and health-contingent wellness programs, which require participants to satisfy a health status standard before the receipt of an award or incentive. In a rule proposed on November 26, 2012, as of January 2014, employers’ ability to reward their employees with incentives for participating in wellness programs will be expanded. The allowed value of incentives under these programs will increase from 20 percent to 30 percent of the total cost of family or individual coverage in 2014. Moreover, this proportion may rise to up to 50 percent of the cost of coverage, at the discretion of the secretaries of Labor, Health and Human Services, and the Treasury, to encourage tobacco-use cessation.

Participatory wellness programs

- Available to all similarly situated individuals

- Non-conditional; that is, they do not require the achievement of any specified standards in order to receive an incentive or reward

- Examples of such programs include reimbursement of fitness center dues, attendance at health education seminars, and participation in tobacco-cessation programs regardless of whether the employee quits smoking or otherwise

- No requirement to meet the five prerequisites applicable to health-contingent wellness programs

Health-contingent wellness programs

- Require participants to satisfy a health status standard before the receipt of an award or incentive

- Must meet five regulatory requirements relating to frequency of opportunity to qualify (at least annually), size of reward, uniform availability and reasonable alternative standards, reasonable design to promote health or prevent disease, and notice of other means of qualifying for the reward

- For example, employees may be required to achieve and maintain exercise targets, quit smoking, or pay a premium surcharge for tobacco use; high-risk individuals may be required to reach certain results on biometric screenings

Rewards may be in the form of discounts, premium rebates, or waiver of cost-sharing vehicles such as deductibles and copayments. Negative incentives in the form of penalties may also potentially be used.

Source: Internal Revenue Services, the Employee Benefits Security Administration, and Health and Human Services Department, Proposed rule wellness programs in group health plans, November 26, 2012, https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2012/11/26/2012-28361/incentives-for-nondiscriminatory-wellness-programs-in-group-health-plans#h-14.

The regulatory landscape is complicated, and employers should ensure that incentive-based programs are non-discriminatory and open to all. Some, concerned that health-contingent employer wellness programs may potentially be discriminatory on the grounds of health status or disability, are seeking to ensure that consumers are protected from unfair practices.23 In addition, workplace wellness programs and the use of incentives are subject to a number of federal and state laws and regulations, including the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, and the Genetic Information and Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008. Further, certain types of incentives have tax implications.

Regulatory constraints are prominent in health care, and they are no less so for employer-sponsored wellness programs.

The proposition is clear: Well-designed and properly targeted employer-sponsored health management programs have the potential to produce changes in health risk and, ultimately, cost savings. Persuading employees to participate, and structuring these efforts for maximum ROI, value, and regulatory compliance, are the challenges. The constraints are formidable.

| Deloitte calculation based upon average annual premium for employer-sponsored health insurance in 2012 (individual premium of $5,615 and family premium of $15,745). Data source: Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, 2012. | ||

| Maximum allowed incentive (%) | Individual coverage (maximum ceiling) | Family coverage (maximum ceiling) |

| Premium variation at proposed incentive allowed value | ||

| @ 20% | $1,123 | $3,149 |

| @ 30% | $1,685 | $4,723 |

| @ 50% | $2,807 | $7,872 |

Looking ahead: The role of incentives in the changing landscape for workplace wellness programs

Given these constraints, one might imagine that employers are dubious about their wellness programs, but the opposite is the case. Some variant of workplace wellness programs can be found in over 90 percent of US companies offering health benefits24 with 200 or more workers. In 2011, investment in health improvement programs was estimated at around 2 percent of companies’ medical spend, with a median annual health improvement spend of $125 per employee (excluding incentives).25

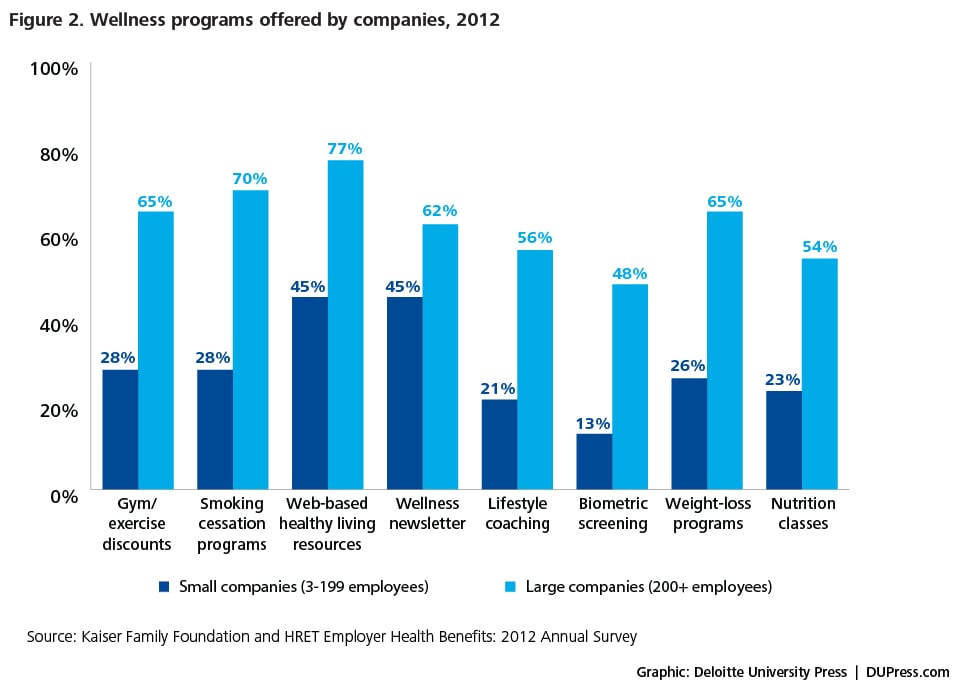

Some employers focus on a small range of benefits such as annual health risk assessments, gym memberships, health fairs, and regular health-oriented communications. Others have introduced comprehensive, fully integrated programs that combine health promotion, incentives for participation or for achievement of health outcomes, and a “healthy workplace” environment (figure 2). Well over one-third (37 percent) of companies surveyed that offer benefits and at least one wellness program do so because wellness programs are bundled as part of the company health plan; a similar number of companies surveyed (35 percent) say they offer wellness programs to improve employee health and to decrease absenteeism.26 A growing number of organizations offer incentives such as cash, cash equivalents such as premium reductions, lottery competitions, and merchandise to encourage participation. One study reports an increase in the proportion of large companies (with 500 or more employees) offering participation-based financial incentives or penalties, with the percentage rising from 33 percent in 2011 to 48 percent in 2012.27 Another study saw the proportion of companies using financial incentives to motivate participation in health management programs rise from 54 percent in 2011 to 61 percent in 2012, with another 21 percent planning to introduce participation incentives in 2013.28

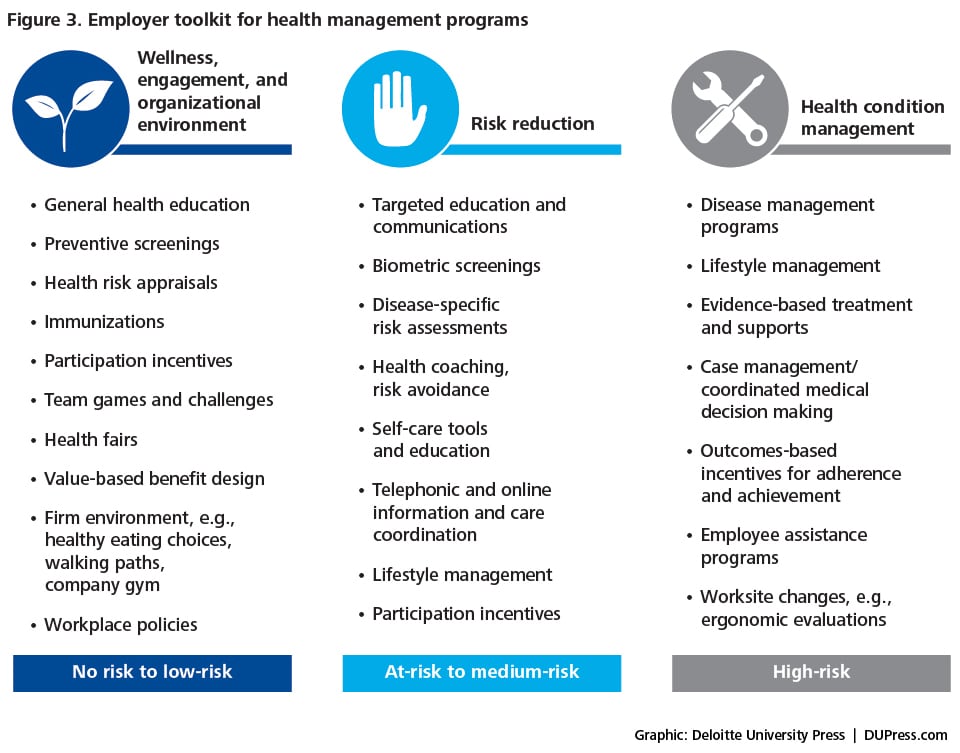

Other resources in the employer toolkit to improve worker health status and to better manage health care costs include benefits management strategies such as guiding employees toward account-based health plans; value-based health management strategies such as the use of surgical centers of excellence, telemedicine, high-performance networks, and adherence to evidence-based treatment protocols;29 environmental changes including healthy cafeteria menus, removal of vending machines, and use of on-site clinics; and communications strategies such as email campaigns, health fairs, and competitive team events (figure 3).

Participation rates in worksite wellness programs are considered to be low,30 typically around 20 percent of an employer’s eligible population.31 In one 2012 survey, 57 percent of employers felt that low levels of engagement and/or program participation were the biggest obstacles to managing employee health.32 Influenced by demographic factors including age, gender, industry sector, income levels, work group, and job type,33 participation rates also vary widely between organizations. One 2010 study reported that more than 30 percent of the companies studied achieved a high participation rate (defined as 50 percent or more of the population eligible for health risk assessments [HRAs]) for completion of HRAs, but that over half of the companies studied fell well short of this mark.34 High participation for both HRA and biometric screening completion has been associated with a trend toward lower health costs, with companies with high participation achieving an average 6 percent health cost growth compared to between 7.2 percent and 7.5 percent for companies with lower participation.35

So given the high levels of corporate activity in wellness programs, the obvious question is, “What makes the most difference in changing employee behavior?” It’s an employer’s chief concern—the constraint holding many back from investing more or widening the impact of their programs to other aspects of their workforce strategies.

Incentive prevalence, design, and incentive value: What do we know?

Incentives are readily understood by employers to play a role in wellness programs, and they are an easy concept for employees to grasp. In their most basic form, incentives are a blunt instrument for raising awareness among employees and shifting the responsibility to them for making better lifestyle decisions and addressing health concerns. Behavioral economics models of individual behavior that assume that individuals respond to incentives36 (tapping into both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation) underpin this shift toward health care consumerism.37 Intended to motivate employees and give them the impetus or inspiration to act, incentives can be both carrots and sticks. And despite low participation rates and uncertainty regarding impact, growing numbers of employers see sufficient value in incentives to warrant investing in incentive programs as triggers to change employees’ behaviors.

Company size is a key determinant of the use of incentive programs. In 2012, 32 percent of small companies surveyed (with 50-100 employees) had incentives and disease management programs that encouraged healthy behaviors. This proportion rose as company size increased, to 48 percent of medium-size companies (100-999 employees), 68 percent of large companies (1,000-2,499 employees), and 73 percent of the largest companies (2,500 or more employees).38 Other industry studies indicate a similar association of incentive use with company size.39 The use of incentives in the mid-size market is expected to grow from 38 percent in 2010 to an anticipated 77 percent in 2013, based on the proportion of companies saying they plan to use incentives by 2013.40 One study reported that in 2011, financial incentives as a percentage of payroll were estimated at 0.9 percent, up from 0.5 percent in 2010.41

Estimates of the average annual value of incentives per employee vary—ranging from $100-$500,42 $200,43 $300,44 and $521.45

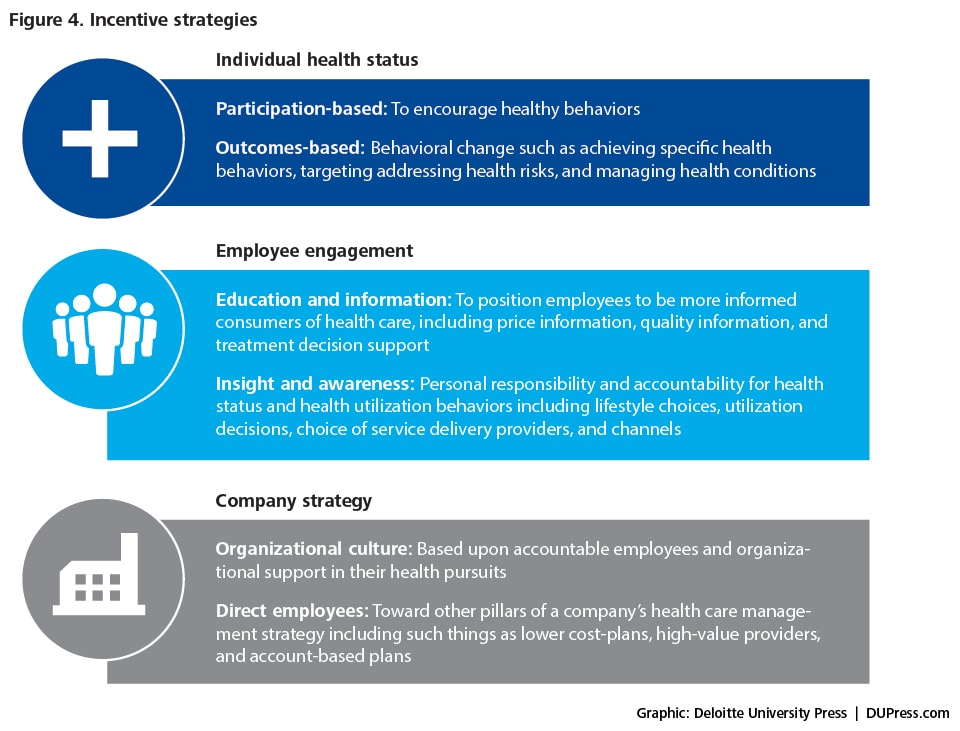

Incentives are most frequently a positive reward, although some firms are introducing penalties (such as higher premiums or higher deductibles) for non-participation or lack of evidence of behavioral change. Incentive program design is split between programs intended to increase attendance or participation (in activities such as attending information sessions or completing HRAs), and outcomes-based (or health-contingent) programs that award incentives after employees achieve specified health results or outcomes (figure 4). Employers are layering higher expectations into their incentive programs, making the receipt of rewards contingent upon completing multiple actions. Industry studies suggest that around 18 percent of large companies have outcomes-based incentives programs currently in place46 and that about another 23 percent plan to introduce such programs in 2013.47 One industry study found that outcomes-based penalty programs were in place at 38 percent of surveyed companies in 2012, up from 19 percent in 2011.48 Some companies are reluctant to use outcomes-based incentives, as they are wary of legal concerns, administrative complexity, fit with company culture, and the potential for discriminatory practices.49 That said, the use of outcomes-based incentives is likely to grow as companies seek greater value from their programs by requiring demonstrable goal achievement before providing incentives.

Based upon survey data that suggests that the average value of incentives is between 3 percent and 11 percent of the average cost of individual coverage in 2010 ($5,049), federal agencies believe that only a few health-contingent or outcomes-based programs currently in operation come “close to meeting the 20 percent of the total cost of coverage threshold” currently allowed by the legislation, let alone the proposed 30 percent threshold that will be effective come January 2014.50

| Consumers’ views | Strongly agree/agree |

| People who deliberately try to improve their health or show measurable improvement should pay less for health insurance than people who do not. | 59% |

| People who are overweight and do not take action to reduce their weight should pay more for health insurance than people who maintain or achieve a healthy weight. | 44% |

| People who smoke and do not take action to try to quit should pay more for health insurance than nonsmokers. | 59% |

| Source: Deloitte survey of health care consumers, 2012. | |

Impact of incentives: Do they work?

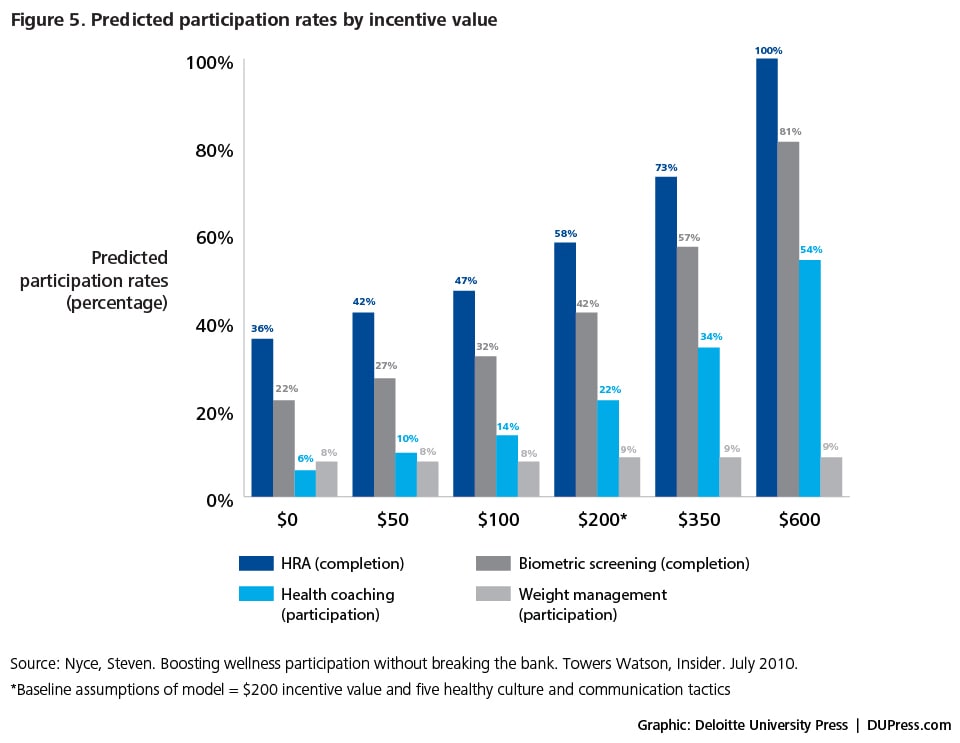

Evidence is emerging about the association between incentive value and participation rates, with a 2009 study finding that HRA participation rates increased by 1.58 percent for every $20 of incentive value.51 Another study projected that participation in HRAs would increase by 7 percent for each $100 increase in incentive value, achieving a maximum 100 percent participation with a $700 incentive.52 Integrating an incentive level of $200 into a health plan is claimed to raise HRA participation rates from between 20 percent and 40 percent (without the use of incentives) to close to 90 percent.53 A 2008 study found a relationship between incentive amount, organizational conditions, and HRA completion. In this study, companies with high levels of health care-related communication and organizational commitment to wellness programs needed an incentive value of $40 to achieve 50 percent participation in completing HRAs; companies with medium levels of communication and organizational commitment required an incentive value of $80, and companies with low levels an incentive value of $120, to achieve the same target.54

A critical question for employers considering incentive programs is the relationship between engagement levels driven by the size of the incentive and the potential impact for the dollar amount invested. Modeling of the likely impact of different incentive values on improving participation rates suggests that HRA completion, biometric screenings, and smoking cessation appear to be responsive to incremental incentives beyond a baseline of $200 in incentive value, whereas participation in weight management programs is not (figure 5).55 Another study reported that an incentive of up to $750 for quitting smoking for up to one year was effective, nearly tripling long-term smoking cessation rates.56 It might be fair to infer that the more difficult it is for an employee to choose compliance, the higher the value of the incentive.

Studies

- An employer-based program for reducing patient cost-sharing for prescription drugs for asthma, hypertension, and diabetes was found to increase prescription medication use by 5 percent per enrollee across the entire enrolled population. Adherence to cardiovascular medications increased immediately and was sustained, with a 9.4 percent increase in adherence after the third year of the program. Adherence for asthma and diabetes medications initially declined, then increased (non-significantly). The total spend (medical and prescription drug) on these two groups did not differ from the spend on the comparison group.57

- A worksite behavioral weight management program investigating the impact of financial incentives over a 28-week period found that, on average, incentivized participants lost 5.2 pounds more body weight than did those without incentives. Although the incentivized programs were more expensive to run, they resulted in much greater weight loss. Thus, the study concluded that incentives had a significant impact upon the effectiveness of a weight-loss program.58

- A five-year study of a healthy lifestyle program in Salt Lake City, which included free annual screenings and financial incentives for achieving and maintaining specified behaviors, found that financial incentives were a primary factor contributing to high participation levels, particularly for younger individuals. Over the duration of the study period, overall medical and prescription drug costs decreased and $3.85 was saved for every dollar spent on the program.59

Many studies focus upon the impact of using incentives on behavior change goals. Several studies examining smoking cessation and weight loss programs found that financial incentives had a positive impact on motivating attendance at such programs.60 However, long-term benefits were not sustained at three,61 six,62 or twelve months post-program completion.63

Timing of incentives: Short-term engagement or initial long-term outcomes—what’s best?

Overall, the impact of using incentives upon the longer-term goals of improving employee health and reducing costs for workplace wellness is only beginning to be better understood. The growth in the use of incentive programs in the workplace has outpaced the accumulation of knowledge necessary to underpin the tactic.

Employers invest scarce resources in incentive programs, and many consider the programs to be successful, but it is difficult to disentangle the impact of incentives from the noise of competing factors. One study, however, suggests that overall, 57 percent of employers believe that their incentive-based programs work better than expected in increasing employee participation and engagement.64 This is particularly the case for “jumbo” organizations (20,000 or more employees), where 58 percent believe these programs perform beyond expectations.65 In one study, 64 percent of those who have measured their programs report they are satisfied with the ROI.66 However, other research has found that around 61 percent of companies either don’t know or don’t measure the results and ROI of their wellness programs. Of those who do measure the results, 4 percent found a strong positive ROI and 29 percent found a small-to-moderate return.67

Establishing the ROI of wellness programs is notoriously difficult; nevertheless, many studies have sought to determine the ROI of various types of programs.68Recently, Baicker et al., in a meta-analysis of 22 studies of worksite disease management and wellness programs that reported health care costs, found that for large employers, medical costs fell by $3.27 for every dollar spent and absenteeism costs fell by $2.73 per dollar spent on these programs. The cost to the employer for the health management programs was estimated at $144 per employee per year, and the use of participation incentives was found in 30 percent of the programs reviewed.69 Serxner et al. found that a comprehensive health and productivity management program delivered a positive ROI in the second and third years of the program following the introduction of incentives in those years, with a resultant ROI of 2.45:1 for the combined period of the program.70

The academic literature and industry studies reflect the many diverse and disparate approaches to wellness and incentives. This has given rise to a case-by-case approach where it may be hard for others to extrapolate from the results obtained at individual companies. An opportunity exists for health plans to use innovative data-driven approaches to the design and development of incentive programs that focus upon capturing proof positive of ROI, which may be of great value to their customers.

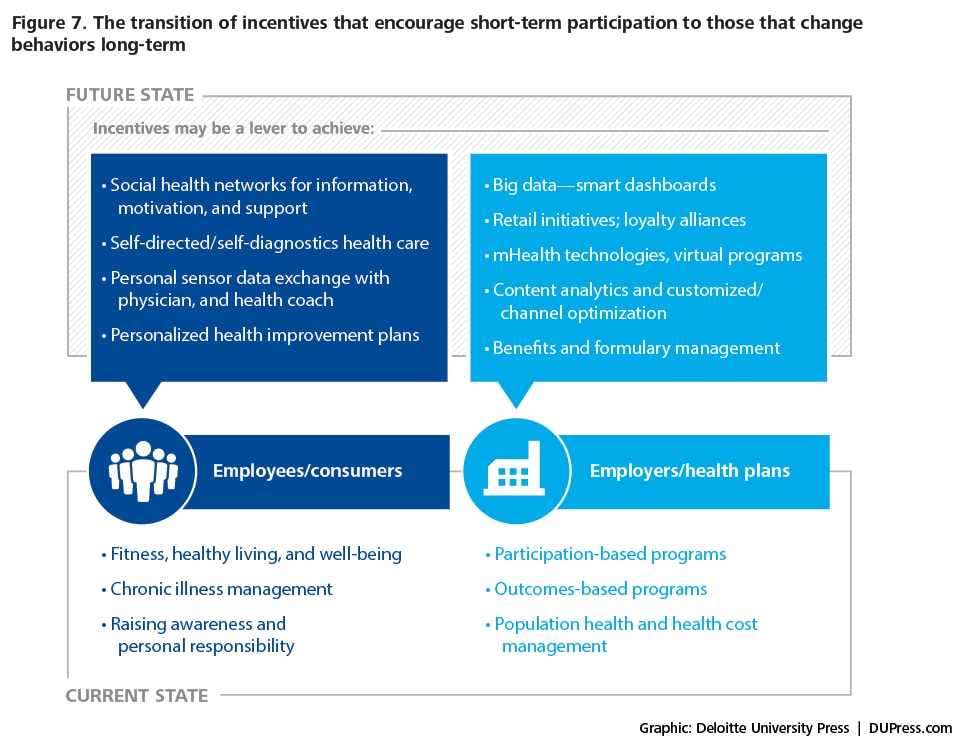

Breaking constraints: Incentives and the future. Our take

In the future, carefully designed incentives will be integral to the worksite health care equation as part of a new model of employee benefits. Emerging digital technologies and social media platforms offer great potential as infrastructures to support change in the next generation of worksite wellness programs. Innovative incentive programs and delivery channels may well offer a bridge between the present state and what employers hope to achieve (figure 7), balancing short- and long-term workforce strategies while breaking traditional constraints around ROI, value, and regulatory compliance.

The rationale for incentive programs offered by employers in the future will be to help individuals overcome the inertia that limits engagement and to disrupt the trade-offs individuals make when pursuing health care goals. The end aim: in an environment of increased health care consumerism and choice, to direct individuals toward better choices about compliance with treatment programs and the pursuit of healthier lifestyles.

Industries that use incentives to reward desired customer behaviors are instructive. In the retail, travel, and banking industries, loyalty programs to connect with consumers, drive purchasing behaviors, and cement long-term relationships are widely used and successful. Programs that are easy to join, offer quick, easily earned initial rewards, and are stratified with different tiers that raise the reward achievement bar have proved to be successful. While expensive to administer, such programs provide food for thought in the design of wellness programs. As health care consumerism increases, individuals will shop for best value and choose an employer, a health plan, or a health program that provides the best chance for better health and that offers a viable and valued “what’s in it for me” benefit. For employers, health care providers, and health plans, such loyalty or reward types of programs offer significant opportunities to use the resulting data for insights useful for customizing incentive strategies that effectively manage value and reduce traditional constraints in targeted employee populations.

The incentives journey is just beginning. For both employers and health plans, well-designed and appropriately targeted incentive programs can deliver the knowledge and strategies necessary to improve overall health and well-being, drive healthy behavior, and reduce costs. Employers and health plans should undertake the education and create the structures necessary to bring the consumer into the healthy living space. Employers and health plans may find a role for behavioral scientists on their health care teams. Incentives can be used to build interest and excitement and can be aligned with other tactics such as cooperative team challenges, health games, chronic disease self-management programs, use of convenient care sites such as onsite clinics and retail clinics, and mHealth technologies.

Incentives to change employee behavior work if specifically targeted to individuals and groups and structured to reward adherence.

Employers should consider:

- Wellness programs will likely increase in importance to employers and health plans, especially in industries that compete for talent as defined contribution program design becomes standard for companies.

- Incentives should be targeted to both short- and long-term behavior changes. Lacking both, results will likely be suboptimal and, in some cases, wasteful. Specific incentives should be accompanied by tools that allow employees to actively engage in self-monitoring and reporting. And these tools should be personalized to the individual’s learning style and grasp of technologies (for example, mobile apps).

- Future incentive programs are expected to evolve to meet the reasonable design and reasonable alternatives requirements of the ACA, ultimately adding a deeper layer of understanding about how good-practice programs can increase access to health care and achieve health gains.

- The ROI for incentives targeted to wellness will likely be significant if a company’s benefits strategy and corporate culture magnify the value of wellness to the employee as well as to the company. Wellness efforts should be top-down and bottom-up to be effective, and rarely will these efforts be effective unless C-suite support is persistent and consistent with the leadership team’s lifestyles.

Are incentive-driven wellness programs important? Yes. To be effective, and to break from the traditional constraints that limit their impact, they should be recalibrated to the changes in the market and an employer’s short- and long-term workforce strategy.

Do all work equally well? No. The fundamentals are in place. In the next five years, incentive programs will likely break the constraints that have hindered their effectiveness.

It’s not a matter of if, but how fast.