Manufacturing opportunity has been saved

Manufacturing opportunity A Deloitte series on making America stronger

28 September 2012

Americans take a dim view of the manufacturing sector’s health and future prospects. Public policies that encourage innovation and talent can help the country regain its global lead in manufacturing.

Introduction

In March 2011, a major economic milestone attracted relatively little notice in the national press. Economic consultants from IHS Global Insight reported that in 2010, China had surpassed the United States to become the world’s leading manufacturing nation, with a 19.8 percent share of global output, compared to 19.4 percent for the United States. China’s share of world manufacturing output had tripled in just 10 years.2

Perhaps the most surprising thing about this announcement was how unsurprising it was.

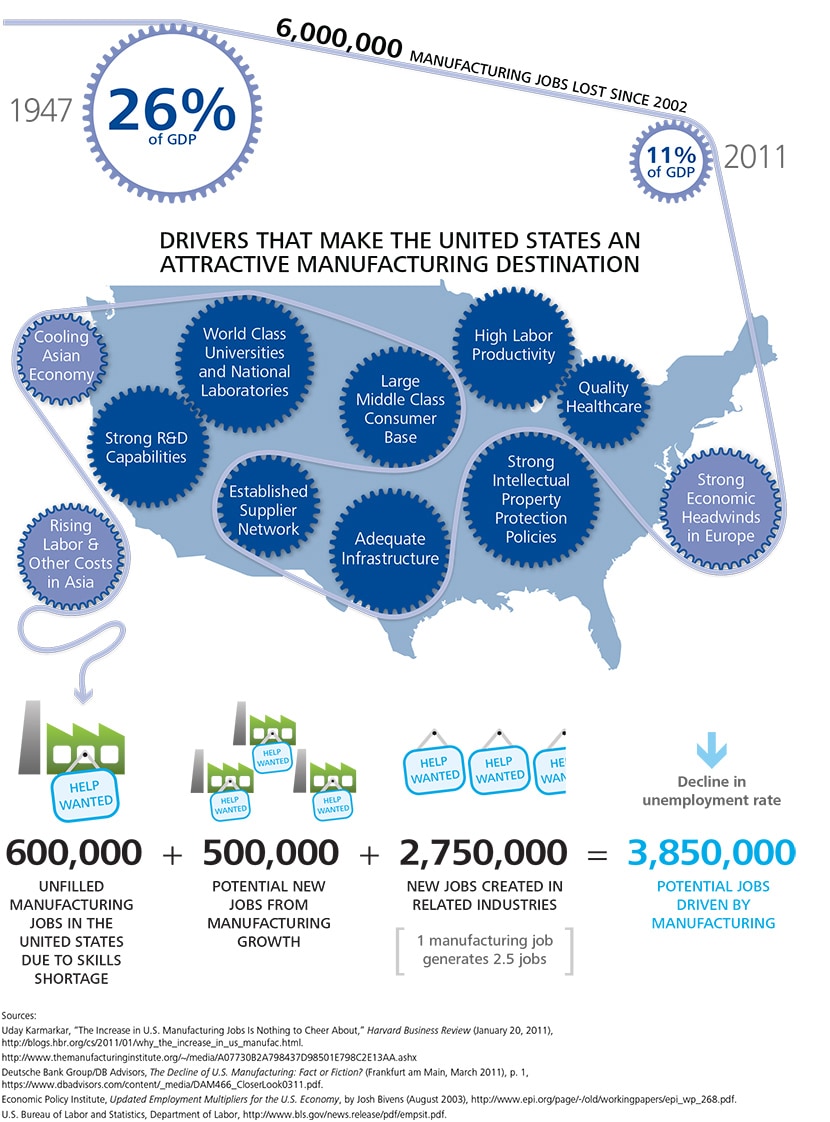

Manufacturing competitiveness and the relative importance of manufacturing to the economy are issues that have been debated for decades, and hundreds of premature obituaries for U.S. manufacturing have been written. Spurring these obituaries has been the undeniably long and steady decline in the importance of manufacturing within America’s overall economic mix. In 1947, for instance, 26 percent of nominal U.S. GDP came from manufacturing. By 2011, that figure had fallen to less than 11 percent.3

This decline has been accompanied by sustained job losses. America has lost about 6 million manufacturing jobs since 2002, 2 million since 2008 alone,4 including 28 percent of its high-technology manufacturing jobs in the last decade as reported by the National Science Board.5 As a result, America’s middle class, which pioneered innovations and technological advancements, has also steadily eroded—as has its economic prosperity.

But U.S. policymakers are beginning to recognize the vital importance of a strong industrial base as emerging economies seize upon the economic benefits of manufacturing, and key developed nations such as Germany demonstrate the resiliency and strength manufacturing adds to the mix. In addition to reviving America’s once prosperous middle class, a competitive manufacturing sector would be a critical catalyst for innovation, providing essential support for sectors including financial services, infrastructure development, customer support, logistics, information systems, healthcare, education, real estate and more. Manufacturing typically generates 2.5 jobs in related industries for each one created directly.6

This report relies on collaborative efforts with a number of organizations working on important issues affecting the manufacturing industry, as well as surveys of American citizens, business and labor leaders, and university and national laboratory executives. It presents a case for optimism—and for hard work. It examines some of the main challenges facing any attempt to cultivate an American manufacturing renaissance, and highlights recommendations that could help the United States overcome these roadblocks.

A crisis of confidence

Manufacturing has been a major contributor to the U.S. economy for more than a century and a half, and Americans retain a consistently high regard for its importance both in terms of its economic contributions and our global standing.

For nearly five years, Deloitte* has been working with the Manufacturing Institute to investigate the average American’s view of manufacturing in the United States. Unwavering Commitment: The Public’s View of the Manufacturing Industry Today reports the results of an annual research program gauging the American public’s perspectives on manufacturing. Findings of the latest annual survey, released in September 2011, suggest that despite frequent swings of public opinion on a wide range of topics, Americans have remained steadfast in their commitment to a strong and globally competitive U.S. manufacturing sector.

They fully understand the importance of manufacturing in job creation; 86 percent agree that manufacturing is directly linked to our standard of living (see figure 1), and 77 percent believe it is very important for our national security. Americans’ support for manufacturing carries over into the topic of job creation as well. When asked how they would prefer to create 1,000 new jobs in their communities with any new business facility, Americans indicated they wanted those jobs to be in the manufacturing sector—more so than any other industry choice.8

Source: Unwavering Commitment: The Public's View of the Manufacturing Industry Today

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents who believe that...

Despite their embrace of manufacturing, Americans do not believe enough is being done to support it. About 83 percent believe the United States needs a more strategic approach to the development of its manufacturing base, 80 percent think the nation should invest more in manufacturing; and 79 percent believe a strong manufacturing base should be a national priority. We also found that the manufacturing industry has several significant challenges in the area of public perception (see figure 2).

Source: Unwavering Commitment: The Public's View of the Manufacturing Industry Today

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents who agree or strongly agree with each statement

Source: Unwavering Commitment: The Public's View of the Manufacturing Industry Today

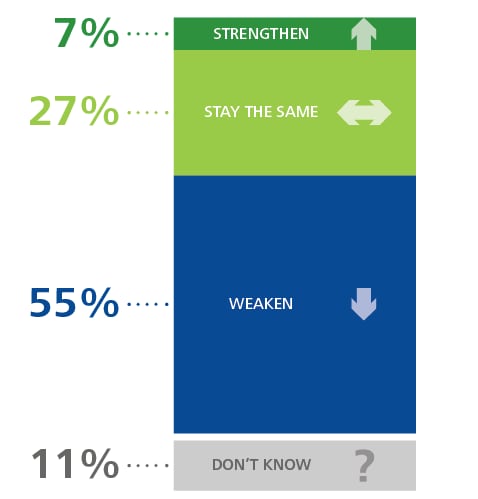

Figure 3. Respondents' views on the longer-term outlook for the manufacturing sector

While Americans generally hold strong views on the importance of manufacturing, they hold negative views about its future in the United States. Americans want stronger policies to support manufacturing and better leadership to support manufacturing competitiveness.

Recent economic data have yielded modest reasons for optimism. In 2011, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs actually rose by 2.05 percent,9 the first increase in more than a decade. But nurturing this growth will require bold and effective policy decisions—and those decisions will be made more difficult by a profound loss of confidence in our leaders’ ability in this arena.

Today, Americans view the manufacturing sector as fragile and unstable. They are concerned about the long-term stability of manufacturing employment, and are equally worried that these jobs are less accessible than they should be. They also fear that manufacturing jobs will inevitably be moved to workers in other countries, and they appear to have doubts about our leaders’ ability to prevent this. These views have remained consistent year after year.

Many Americans, in fact, believe that we have already lost the manufacturing race. Only 7 percent believe that U.S. manufacturing competitiveness is likely to get stronger, while 55 percent say it is becoming weaker (see figure 3).10 And unfortunately, they are solidly pessimistic about the ability of government or business leaders to reverse this trend.

Most Americans agree, for instance, that the federal government should play an important role in building and sustaining a healthy environment for manufacturing. But only 26 percent believe that it is doing so.

CEOs fare only a little better. “Less than half of Americans believe that current business leaders are creating a competitive advantage for the U.S.”11

CEOs and the American public agree

These views are shared by business leaders. A Deloitte global survey of manufacturing CEOs conducted in conjunction with the U.S. Council on Competitiveness also found serious concerns about U.S. manufacturing competitiveness. According to the Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index developed by Deloitte and the Council, the United States is the fourth most-competitive manufacturing nation and is expected slide to fifth place within five years (see figure 4).

In less than a decade, tectonic shifts in regional manufacturing competence have created a “new world order” for manufacturing competitiveness. Asia is the world’s most competitive location for manufacturing—and will be for the foreseeable future, barring significant macroeconomic shocks such as war, economic collapse, natural catastrophe or major government interventions.12

Source: Deloitte and U.S. Council on Competitiveness, 2010 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index

Figure 4. Expected change in manufacturing competitiveness in five years

Research methodology and background for this report

For several years, Deloitte has had the privilege of working with a number of global and national organizations to study the complex linkages between manufacturing and economic prosperity and to understand what nations can do to reap the benefits of globally competitive manufacturing capabilities. Working in collaboration with the World Economic Forum (“the Forum”), the U.S. Council on Competitiveness (“the Council”), and the Manufacturing Institute, Deloitte has collected input directly from policymakers and business, labor, academic, and scientific leaders from around the world to identify ways in which public-private sector collaborations enable economic growth, create jobs, and drive innovation and talent development within manufacturing.

The results of these efforts have included a number of in-depth research reports that have been shared with business leaders and policymakers at important venues on the national and global stage, including the 2012 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland and several sessions with policymakers representing Congress and the administration. While the project identified many common assessments and recommendations for improving U.S. manufacturing competitiveness, each report also delivered unique perspectives critical to this important debate. The results of these initiatives form the basis for the analysis and recommendations in this study. Summaries of each initiative can be found in the appendix (see PDF).

Regional implications will arise as North America, South America, Europe, and Asia challenge one another for dominance in manufacturing. Many rising countries appear destined to be important only within select manufacturing sectors, while others possess the breadth and depth of resources and capabilities to be dominant global players. One thing is certain: government policies within these regions will play an important role—for good or bad—in each country’s competitiveness.

Public policy and the competitive paradox

The Competitiveness Index leads us to another striking finding. Manufacturing is declining in Western countries with more “enlightened” social and environmental policies and rising in emerging markets with large governmental interventions for manufacturing. Within these developing countries, some manufacturers are even government-owned. Clearly, a new model is emerging. Many governments, especially in emerging regions, are aggressively competing for manufacturing dominance.

Nations sliding down in competitiveness, moreover, are losing a core economic strength, a key link in the innovation equation of: research, design, manufacture, after sales. These factors are synergistic, and without the manufacturing step, much know-how is lost. China, India and Korea are aware of this and their public policies further their competitive advantage.

Regardless of a nation’s economic or political system, however, manufacturing can play a key role in its prosperity. Economies based primarily on services could become second tier in the absence of a vibrant manufacturing sector and the commercial ecosystem that grows from it.

But manufacturers cannot go it alone. Governments must play their part by developing policy and national manufacturing strategies that are collaborative, integrated, focused, and effective.

The elements of competitiveness

To explore how the global manufacturing ecosystem is evolving, the World Economic Forum, along with manufacturing specialists from Deloitte, embarked on a project called The Future of Manufacturing to identify the factors most likely to shape the future of competition for both countries and companies. The key findings of this study were released at the Forum’s 2012 annual meeting in Davos, including a critical finding for policymakers concerned with job creation and economic growth.

Based on recent research at the Harvard Kennedy School and the MIT Media Lab, the project concluded that manufacturing, or the “ability to make things,” is an essential driver of knowledge creation, innovation, capability development, and economic prosperity. The more advanced the manufactured product, the greater the prosperity of the nation. The linkage between manufacturing capabilities and economic prosperity is a much stronger predictor of a vibrant, successful, and growing economy than any other measure typically used by economists. Simply put: manufacturing matters.13

The linkage between manufacturing capabilities and economic prosperity is a much stronger predictor of a vibrant, successful, and growing economy than any other measure typically used by economists.

Deloitte’s research with the Forum and the Council also concluded that the future of manufacturing—separating winners from losers—would be driven primarily by the following factors: talent, innovation, energy, and government policy.

Figure 5. Manufacturing opportunity in the United States

Talent

Talented human capital will be a critical differentiator for the prosperity of countries and companies. Millions of manufacturing jobs around the world can’t be filled today due to a growing skills gap. In the United States, more than 600,000 such jobs can’t be filled due to skills shortages.14 Despite high unemployment rates in most developed economies, companies are struggling to fill manufacturing jobs with the right talent. And emerging nations can’t increase their growth without more talent. Access to talent will only become more important and more competitive. Companies and countries that can attract, develop and retain the highest-skilled talent—from scientists, researchers, and engineers to technicians and skilled production workers—will be better positioned to come out on top.

With the prosperity of nations hanging in the balance, policymakers must actively seek the right combination of trade, tax, labor, energy, education, science, technology, and industrial policy levers to generate the best possible future for their citizens.

Innovation

The ability to innovate quickly and effectively will be another important factor in the success of countries and companies in the future, as measured by growth in GDP, market share, and profitability. Companies must innovate to stay ahead of competition, and they must be supported by infrastructure and policies that support breakthroughs in science and technology as well as dedicated investment budgets that permit long-term pursuits. In the 21st century manufacturing environment, the ability to develop creative ideas that address new and complex problems with innovative products and services will be all-important.

Energy

Affordable clean energy strategies and effective energy policies will be a top priority for manufacturers and policymakers, and they serve as another important differentiator of highly competitive countries and companies. The demand for and the cost of energy will only increase with future population growth and industrialization. Environmental and sustainability concerns will demand that nations respond effectively and responsibly to the energy challenge. All nations will seek competitive energy policies that ensure affordable and reliable energy supplies for manufacturing, and will be forced to seek new ways of manufacturing from energy-efficient product designs to energy-efficient operations and logistics. Collaboration between company leaders and policymakers will be an imperative in solving the energy puzzle.

Government policy

Finally, the strategic use of public policy to further economic development will become increasingly important, placing a premium on collaboration between governments and business leaders to create win-win outcomes. With the prosperity of nations hanging in the balance, policymakers must actively seek the right combination of trade, tax, labor, energy, education, science, technology, and industrial policy levers to generate the best possible future for their citizens. In a complex and interdependent global economy, governments must pull the right levers at the right time while remaining mindful of unintended consequences. Companies, in turn, must become more sophisticated and engaged in their interactions with policymakers to help strike the balanced approach necessary to enable success for all.

The Competitiveness Index developed with the Council provides further evidence supporting these findings. While manufacturing competitiveness traditionally has been judged by labor, materials, and energy costs,15 today’s manufacturing executives note other qualitative factors (see figure 6) that influence American competitiveness:

- education and workforce preparation

- innovation

- economic, trade, financial and tax issues

- infrastructure and

- energy policy

Each factor plays an important role in determining manufacturing competitiveness. Government is more central to some than others; in matters of trade, regulation and taxation, obviously, it is central. But government has a role to play in each—a role that will help determine whether U.S. manufacturing can remain competitive in the future.

Source: Deloitte and U.S. Council on Competitiveness, 2010 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index

Figure 6. Drivers of manufacturing competitiveness (global vs. the United States and Canada)

Making America a more attractive place to conduct business: Action steps for policymakers

To develop specific recommendations regarding U.S. competitiveness, Deloitte and the U.S. Council on Competitiveness sought the input of CEOs, university presidents, leaders of U.S. national laboratories, and labor union leaders. Deloitte conducted one-on-one interviews with dozens of representatives from these constituent groups across America and then distilled the recommendations. These interviews are documented in the Council’s Ignite series of reports, which form the basis for the recommendations presented here.

An overarching concern consistently and almost unanimously expressed by executives, university presidents and national laboratory leaders was policy, legislative and regulatory uncertainty. Participants suggested that this uncertainty directly affects both short- and long-term decision making. Business leaders emphasized that they routinely develop strategic business plans and supporting investments with 10– to 15–year horizons, but they must work under government policies that do not provide similar long-term clarity or stability. In particular, many suggested that this uncertainty affects critical cost and competitiveness variables. University presidents and national laboratory leaders noted uncertainties tied to funding stability and the consistency of programs centered on education and R&D.

Participants cited issues such as the clarity and permanency of R&D tax credits, competitive tax rates, the ratification of free trade agreements, tort reform, financial reform, and policies affecting health care, labor, innovation, energy, and carbon regulation, as well as long-term funding for important research. Clear and stable competitive policies in these areas would generate tremendous opportunities for American manufacturers and make the United States an attractive place to invest and conduct business.

It is important to note that these recommendations were not entirely consistent among stakeholders. While many agreed on a number of topics, there were some differences among the stakeholder groups; the following recommendations are culled from those outlined in one or more of the Ignite reports.

Education and workforce preparation

Manufacturing CEOs agreed that worker talent—specifically the talent that drives innovation—trumps all other factors in gauging competitiveness.16 Developing this talent through education, then, is the most important element in ensuring manufacturing success.

Talent shortages

The existence of a substantial and growing U.S. skills gap in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) disciplines is well documented, and the gap is having obvious effects on competitiveness. In the 2011 survey conducted by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute, 67 percent of responding manufacturers reported moderate to severe shortages of available, qualified workers; 56 percent anticipate that these shortages will grow worse in the next three to five years.

And the talent shortage inevitably affects American innovation. As the Baby Boomer generation wanes, losses of skilled workers, scientists, researchers, engineers, and teachers will have a lasting impact on manufacturing competitiveness and thus the country as a whole. Without radical action, most 21st century workers are likely to be less skilled than their Baby Boom counterparts.17

In an era of widespread unemployment, manufacturers reported that 5 percent of positions at their firms were unfilled due to a lack of qualified candidates. As noted above, that represents more than 600,000 jobs that can’t be filled today because employers can’t find people with the right skills. Seventy-four percent indicated that employee shortages or inadequate talent in skilled production roles were hurting their ability to expand operations or improve productivity. Eleven percent of respondents were considering relocating, and among these, the most commonly cited reason was greater access to qualified talent.

Survey respondents also indicated that the workers hardest to find today include machinists, operators, craft workers, and technicians—and these are the positions they also expect to be hit hardest by retirement over the next three to five years.18 As these experienced employees retire, finding younger talent to replace them will become an increasingly difficult challenge.

STEM teaching deficiencies

One reason for the skills gap is a long-term shift in educational focus, both in the classroom and in teacher training programs. According to many of the university presidents and national laboratory leaders participating in Ignite 2.0: Voices of Voices of American University Presidents and National Lab Directors on Manufacturing Competitiveness, in recent decades, the emphasis in teacher education has shifted strongly away from subject-matter content and toward pedagogy, the theory of teaching itself.19 This has led to critical deficiencies in the teaching of STEM subjects in particular.

Most of the business executives participating in Ignite 1.0: Voices of CEOs on Manufacturing Competitiveness said U.S. students are less interested and perform more poorly in science and engineering disciplines than foreign students.20 Put simply, many American educational programs are not teaching STEM topics well, and just as importantly, they are failing to make these disciplines seem important, interesting or rewarding to students.

Education leaders should be aligning educational pathways in degree programs to portable, industry-recognized skills credentials, creating more “on and off” ramps, says Emily Stover DeRocco, former president of The Manufacturing Institute. This could help close the gap between the skills manufacturers need and those held by graduates entering the workforce.

The global business community does report concerns regarding engineering graduates from institutions in emerging markets, due to ongoing questions about instructor qualifications, soaring student-teacher ratios and the variability of curricula. Despite these concerns, however, the emergence of a large and skilled technical workforce is one of the most important factors driving the competitiveness of nations such as China and India.21

Perceptions of manufacturing careers are also are hurting the United States’ ability to develop a highly talented workforce. In another study conducted by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute, 18–24-year-olds rank manufacturing dead last among industries in which they would choose to start a career.22 Moreover, even students pursuing STEM disciplines often fail to translate their studies into technical careers. According to a recent study by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, more than 30 percent of engineering, computer science, and mathematics majors choose careers in business or professional services rather than in science and engineering.23

America is still a vibrant and innovative country, and its manufacturers still represent an extremely valuable knowledge base. But our ability to innovate and to address complex scientific, technological, and social challenges is in jeopardy. Most of the leaders participating in the various reports cited throughout this document agreed that U.S. manufacturing competitiveness can be improved only if Americans become more interested in manufacturing through educational programs that portray the industry as a valuable career choice with good employment opportunities. Furthermore, we need to arm students with the right technical and problem-solving skills through flexible education pathways that lead to advanced degrees or certifications.

Recommendations: Educated workforce

Participants in the Ignite series offered the following recommendations to improve America’s ability to develop an educated and prepared workforce.24 While they recognized budget challenges and the imperative of reducing the federal deficit, participants consistently felt that funding in these areas were essential to U.S. manufacturing competitiveness.

Maintain long-term, predictable federal and state support for universities, community colleges, and the nation’s research and science infrastructure.

- Focus U.S. public and higher education on developing skills in science, technology, engineering, and math. The revival of America’s STEM talent pool must begin in the earliest grades with teachers who are fully prepared to teach and inspirethe next generation of professionals. As part of this effort, the United States should:

- At the state level, adopt consistent standards and curricula for STEM disciplines.

- These standards should be tied to metrics followed in other leading manufacturing economies.

- Provide guidelines and incentives to attract and retain primary and secondary STEM teachers who are true subject-matter experts that are able to prepare students for degrees or certifications.

- Incentives such as continuing education opportunities could be offered to current STEM teachers. The next generation of teachers could be cultivated with scholarship programs that attract top high-school talent to pursue STEM education. K–12 systems could be offered discipline-linked salary tiers similar to those provided to college and university professors to reward teachers for developing and maintaining subject-matter expertise.

- Develop flexible higher education tracks that foster STEM literacy through community colleges, vocational trade schools, work-training programs, etc.

- Support state universities’ efforts to attract high-caliber students to STEM programs and increase the number of graduates in STEM disciplines.

- Develop initiatives that promote and market manufacturing as a vital and high-value industry with rewarding long-term career opportunities for high school and college students.

- This commitment should involve focused, creative, and measurable initiatives targeted at today’s and tomorrow’s students—and parents.

- Build government-industry partnerships that provide incentives for prospective workers to pursue careers in science, engineering, and manufacturing.

- Advance performance-based legislation and incentives such as the America COMPETES Act, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act, the Investing in Innovation Fund, and the Race to the Top and Teacher Incentive funds.

- Benchmark best practices from other countries that are succeeding in attracting and retaining top STEM talent.

- Expand programs such as Helmets to Hardhats® and project labor/community workforce agreements that hire and train active military personnel, disadvantaged youths, and unemployed veterans for successful careers in the skilled trades.

Innovation

Across the spectrum of policy, from the tax code to the direct incubation of small businesses, government has an important role to play in boosting innovation.

A healthy domestic manufacturing base is important if the United States is to benefit from emerging technologies in the future. For example, the shifting of television production to Asia cost the United States its opportunity to develop next-generation flat panel technology, a competency that later proved instrumental in the design and manufacture of solar panels.25

The competitive landscape

Globalization and technological progress, especially in advanced communications, have put American workers into direct competition with rising, leading-edge talent pools worldwide. And while many of the leaders participating in the Ignite series agreed that the U.S. should not engage in a “race to the bottom” with other nations concerning wages, nationwide discussion is increasing on the topic of how to reestablish the United States as an attractive and competitive location for R&D and customer support functions. Bringing much of this capability back is becoming a profitable and efficient decision for companies.26

Many felt ‘manufacturing’ is in fact a misnomer, since it fails to address the many sectors, including universities and colleges, national laboratories and other private and public bodies that support the manufacturing ecosystem. And while many participating in the Ignite series felt that the United States is still capable of manufacturing high-quality goods at very competitive prices, they also believe that competing on wages alone would not be beneficial to American manufacturing and that the United States must focus on and support the R&D and innovation phases of manufacturing if it is to retain any lasting edge in competitiveness.

Fostering a climate for manufacturing innovation

According to CEOs around the world, other nations have done a much better job in creating, pursuing, and communicating national innovation strategies (see figure 7). Germany, for instance, has established a comprehensive national strategy across all its federal ministries with goals and timetables for critical fields, and it greatly increased its research and development funding.27 Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute, jointly funded by government and private contracts, is Europe’s largest applied research organization, conducting both fundamental and applied research and early-stage commercialization development.28

Many felt ‘manufacturing’ is, in fact, a misnomer since it fails to address many sectors, including universities and colleges, national laboratories, and other private and public bodies that support the manufacturing ecosystem.

Many CEOs participating in Ignite 1.0 said they would like to see the United States foster similar instruments for manufacturing innovation. They believe that government investments in the areas of science, technology, and engineering can substantially improve manufacturing competitiveness. Such investments could include the establishment of support research institutions, technological supports for manufacturers, and the encouragement of local manufacturing clusters.29

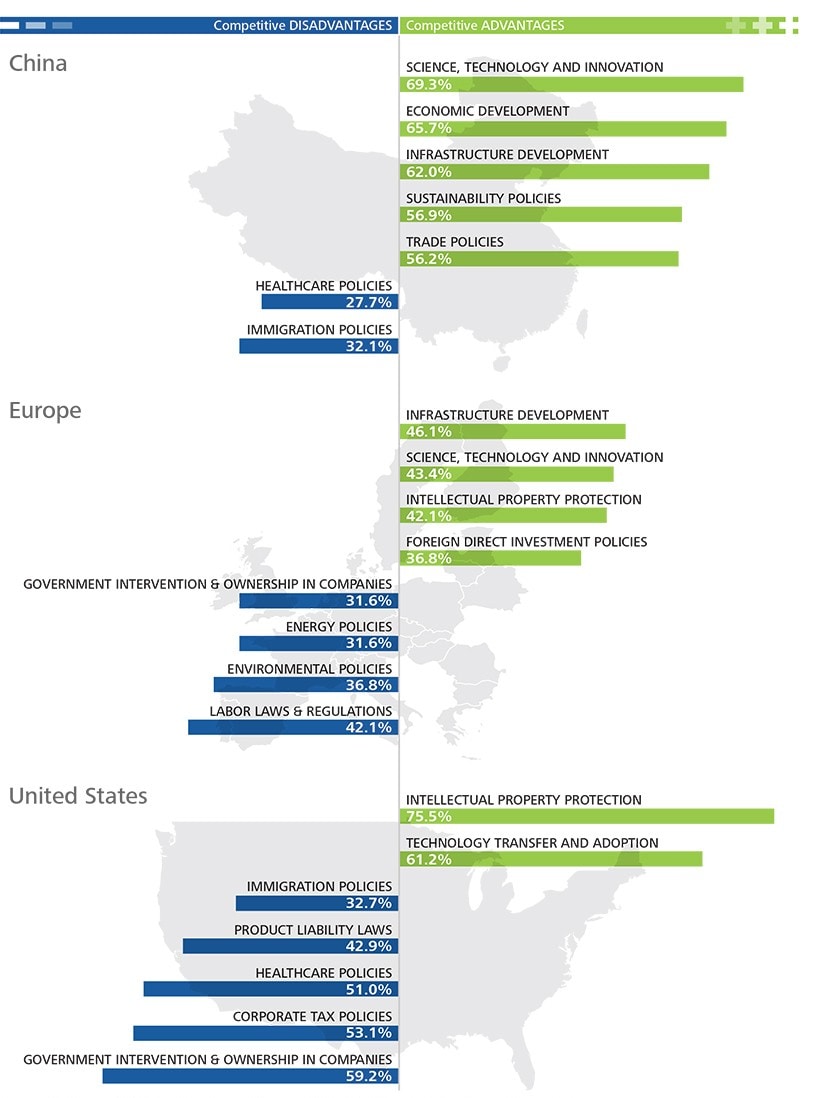

Source: Deloitte and U.S. Council on Competitiveness, 2010 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index

Figure 7. Policy advantages and disadvantages (percent indicating advantage or disadvantage)

Co-locating R&D and manufacturing

University leaders and national research laboratory executives participating in Ignite 2.0 underscored a similar point. Many advocate government support for sector-specific industrial clusters that place universities, national laboratories, and companies in close proximity to optimize the commercialization of new ideas, citing examples such as the biomedical clusters in Ohio and Massachusetts.

Co-located research and manufacturing connections encourage continuous product and process improvement promoting the maturation of basic research into applied research, and the transition of pilot projects into full commercialization. They would enhance the quality and return on investment of breakthrough discoveries.30

Recommendations: Innovation

Participants in the Ignite series offered the following recommendations to improve America’s ability to innovate.

Establish a consortium of business, university, labor, and political leaders to develop long-term U.S. manufacturing goals with a 15– to 20–year development horizon.

This consortium should work collaboratively to craft investment and development programs as well as the educational, technological, and intellectual infrastructure needed to support progress toward those goals.

- Develop a U.S. innovation strategy that establishes programs to support basic and applied research into manufacturing innovation and commercialization.

- This strategy should aim at eliminating barriers to collaboration among universities, laboratories, and other private and public entities. Its programs should be supported with long-term funding mechanisms that insulate them from the uncertainties of election cycles. A major goal should be the establishment of public and privately funded pathways to drive innovative ideas and technologies through the “valley of death”—where many inventions and new technologies tend to die—to commercialization.

- Increase the number of public-private industry clusters that convene research institutions, industry, and the best talent to focus on advancing research and full life-cycle commercialization.

- Encourage national laboratories to develop mission-driven innovations crucial to national interests while broadening the definition of national interest to include economic development.

- This would include leveraging the ability of America’s national laboratories to drive applied research on the journey to commercialization, as well as the establishment of succinct and concise goals in areas important to the United States for economic development as well as national security, defense, energy, etc. This effort should also support the laboratories’ role in community outreach programs, such as educational outreach to local primary and secondary schools, nearby corporations, and the community at large.

Economic, trade, financial, and tax issues

Regulatory compliance costs, labor laws and regulations, and intellectual property protection and enforcement all have a strong influence on competitiveness and growth. A 2008 study found that U.S. manufacturers on average spend nearly 18 percent more on non-production expenses—the cost of energy, taxes, employee benefits, torts, and pollution abatement—than do their counterparts in the nation’s major trading partners.31

Tax policy

Americans show strong support for tax policies that support competitiveness; 69 percent agree that tax cuts for businesses and individuals create jobs, while 65 percent support tax incentives for manufacturing.32

High tax burdens. Taxes represent a substantial burden for U.S. manufacturing. In 2011, the United States had the highest corporate tax rates among the OECD nations, up from second place in 2010.33 Critics of U.S. corporate tax policy note that the nation’s rates have remained virtually unchanged for the past two decades, even as competitor nations have lowered theirs.34 High corporate tax rates (as well as questions regarding permanency of tax credits and policies) reduce manufacturers’ ability to invest with confidence over the long term.

Repatriation could boost competitiveness. Business leaders interviewed for the Ignite series often cite the ability to repatriate cash from abroad as a means to boost competitiveness. The United States is the only G8 member that does not employ a territorial tax rate policy, which taxes only income earned inside the nation’s borders.35 Even a policy allowing U.S. firms to repatriate cash at a lower tax rate could help level the playing field between domestic and foreign manufacturers and encourage U.S. companies to increase domestic investments.

R&D tax credit. Still another pertinent issue mentioned by Ignite participants concerns the research and development tax credit, which has existed in varying forms as a “temporary” but perennially reauthorized measure for nearly three decades, earning it what the Journal of Accountancy has called “well-deserved reputation for complexity and uncertainty.”36

Intellectual property protection

Protecting American intellectual property—whether by trademark for a new brand or by patent for a new technological innovation—is essential to maintaining competitiveness. A 2005 National Bureau of Economic Research study, for instance, concluded that improvements in intellectual property rights result in increased technology transfer by multinational enterprises.37

Trade policy

International trade agreements, too, are an obvious competitive factor in an era in which 95 percent of our manufacturers’ potential customers live outside the United States.38 While the topic of trade policy was consistently important to all stakeholders participating in the Ignite series, there were clear similarities and differences between business and labor leaders.

For example, both groups felt more needs to be done to ensure the enforcement of U.S. rights under existing trade agreements, and to ensure compliance with WTO including legal action against countries that violate trade policy and limit the United States’ ability to compete fairly in the global marketplace. Both groups also felt the United States should establish fair and equitable free trade agreements that address various aspects of the business environment in competing countries, including labor laws and regulations concerning minimum wages, child labor, working conditions, human rights, environmental protection, and workplace safety.

Where the groups differed concerns the notion often described as “fair trade vs. free trade.” While many executives interviewed by Deloitte and the Council support recent free trade negotiations, such as those with Korea (which promise to boost U.S. exports by $10 to $11 billion), Colombia, and Panama, many labor leaders interviewed for Ignite 3.0 expressed frustration with these agreements, calling them unfair, one-sided, and detrimental to national security, U.S. industry, and American workers.39 They argued that narrowly defined trade policies alone are not sufficient to position U.S. businesses fairly in the international marketplace and may be detrimental to domestic production.40

Infrastructure

Transportation infrastructure is vitally important to U.S. manufacturing competitiveness in terms of attracting business investment, improving the effectiveness of logistics, the movement of raw materials, and in producing finished products on time and at minimum cost. Modern power grids and telecommunications networks play similar roles in moving energy and information.

In addition to improving America’s roadways, airports, waterways, electric grid, and broadband capabilities, infrastructure investments also can create long-term, high-paying jobs in the United States, putting thousands of people back to work while encouraging private investment. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, the largest public works project in U.S. history, is often cited as an example of how large, nationally supported infrastructure projects can create long-term benefits and prosperity. Proponents of greater infrastructure investment also point to recent Congressional Budget Office estimates which suggest that every dollar of infrastructure spending generates an additional 60 cents in economic activity.41

Recommendations: Economic, trade, financial, and tax systems

Participants in the Ignite series offered the following recommendations to improve America’s economic, trade, financial, and tax systems.

- Institute a comprehensive reform of federal corporate taxes that provides long-term clarity and stability and offers globally competitive rates.

- This should involve the reduction or elimination of taxes on repatriated foreign earnings and permanent research and development tax credits that favor U.S.-based innovation, continuing STEM education, and the acquisition of R&D equipment and infrastructure.

- Develop a benchmarking process to analyze the impact of government regulations on global competitiveness.

- This could help diminish the cost and complexity of regulatory compliance. The nation’s overlapping federal, state, and local regulations are challenging to navigate and can create barriers to innovation and growth.

- Develop a new trade promotion and fast-track authority to quickly establish fair and equitable free trade agreements.

- One task should be the establishment of a set of principles to guide the formulation of beneficial trade agreements that address environmental and worker protections and resolve trade imbalances.

- Aggressively pursue the closure of a commercially meaningful WTO Doha Agenda to lower global trade barriers.

America’s competitors understand the importance of modern infrastructure. In 2005, China devoted 7.3 percent of its GDP to infrastructure development; by 2009, this share had risen to about 9 percent. A large share of this spending went to the rail sector, which saw a 70 percent increase in fixed-asset investments.43

Infrastructure improvement is perhaps the clearest example of how government action can improve manufacturing competitiveness – especially in areas that improve the efficiency of exports as well as job creation. And the opportunity is not limited to the federal government. States, for example, can help metropolitan regions resolve issues with traffic flow.

Energy

Clean, reliable energy is an all-important element of manufacturing production. With increasing demand for and limited supplies of traditional energy sources, market forces will play a crucial role in driving the development and adoption of alternative forms of energy and its efficient use. Alternative energy sources also promise a competitive advantage for any nation that can develop them effectively.44

Alternative energy solutions could create many more manufacturing jobs. U.S. labor leaders, noting forecasted growth in this area from 9 million jobs in 2007 to as many as 37 million in 2030 (many of them not subject to offshoring to overseas markets), strongly support policies to promote the research, development and production of alternative energy (solar panels, wind turbines, advanced batteries, etc.).45 They also favor an extension of the Advanced Manufacturing Tax Credit, which provides incentives for investments in the advanced energy products, and may prove critical if America is to lead the next generation of manufacturing.46

Recommendations: Infrastructure

Participants in the Ignite series offered the following recommendations to improve America’s infrastructure.

To ensure long-term funding, the United States should create a national infrastructure bank—a government-owned yet independent and professionally managed entity responsible for managing investment in and the long-term financing of regional and national infrastructure projects.

- Prioritize support for projects that improve export capabilities and promote the efficient movement of goods, including air traffic infrastructure, ports, railroads, roads, nuclear facilities, the electric grid, and IT infrastructures. To win approval, projects should create jobs within the United States.

- Develop incentives to encourage the creation of private-public partnerships to complete vital infrastructure projects.

- Assist state and local governments with funding infrastructure projects by providing federal guarantees to lower borrowing costs and minimize disruptions to the municipal bond market.

- To further this effort, Congress should reinstate the Build America Bonds program, which issued $181 million in taxable municipal bonds before expiring at the end of 2010.

- Create a comprehensive national energy policy that encourages reinvestment in current infrastructure; furthers energy efficiency and conservation; and balances investment across a diverse portfolio of all fuel sources, including solar, wind, and nuclear power as well as critical U.S. assets in coal, natural gas, and offshore oil.

Conclusion

The stakeholders participating in the joint efforts between Deloitte, the Forum, the U.S. Council on Competitiveness, and the Manufacturing Institute understand that U.S. manufacturing is at a crossroads. Low-cost, basic manufacturing is unlikely to ever recover its former importance in our economy; our long-term opportunities lie in increasingly complex and emerging technologies—and in America’s ability to lead in the development of such breakthroughs. Taking full advantage of these opportunities will require sustained commitments to rebuilding our education system and creating and cultivating an effective ecosystem of public-private research and product development.

Most Americans understand that our economic success is closely linked to our ability to make useful and valuable products. Government can advance efforts to retain that ability by supporting the solutions summarized in this report, which can help the United States regain its global lead in manufacturing for many years to come.

Low-cost, basic manufacturing is unlikely to ever recover its former importance in our economy; our long-term opportunities lie in increasingly complex and emerging technologies—and in America’s ability to lead in the development of such breakthroughs.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.