Riding the next wave of investments in the US petrochemical industry Learn from evidence to avoid a bumpy ride

06 September 2018

As the United States prepares for the next wave of petrochemical investments, companies must take steps to not repeat mistakes of the past, and overcome challenges that may lie ahead.

The geographical focus of global investments in the petrochemical industry is going through a flux over the past few years. Earlier, the Middle East was the primary recipient of petrochemical investments. But preferable investment destinations have shifted over time, with the United States and China now receiving an increasing share.

Learn More

Subscribe to receive Oil & Gas sector updates

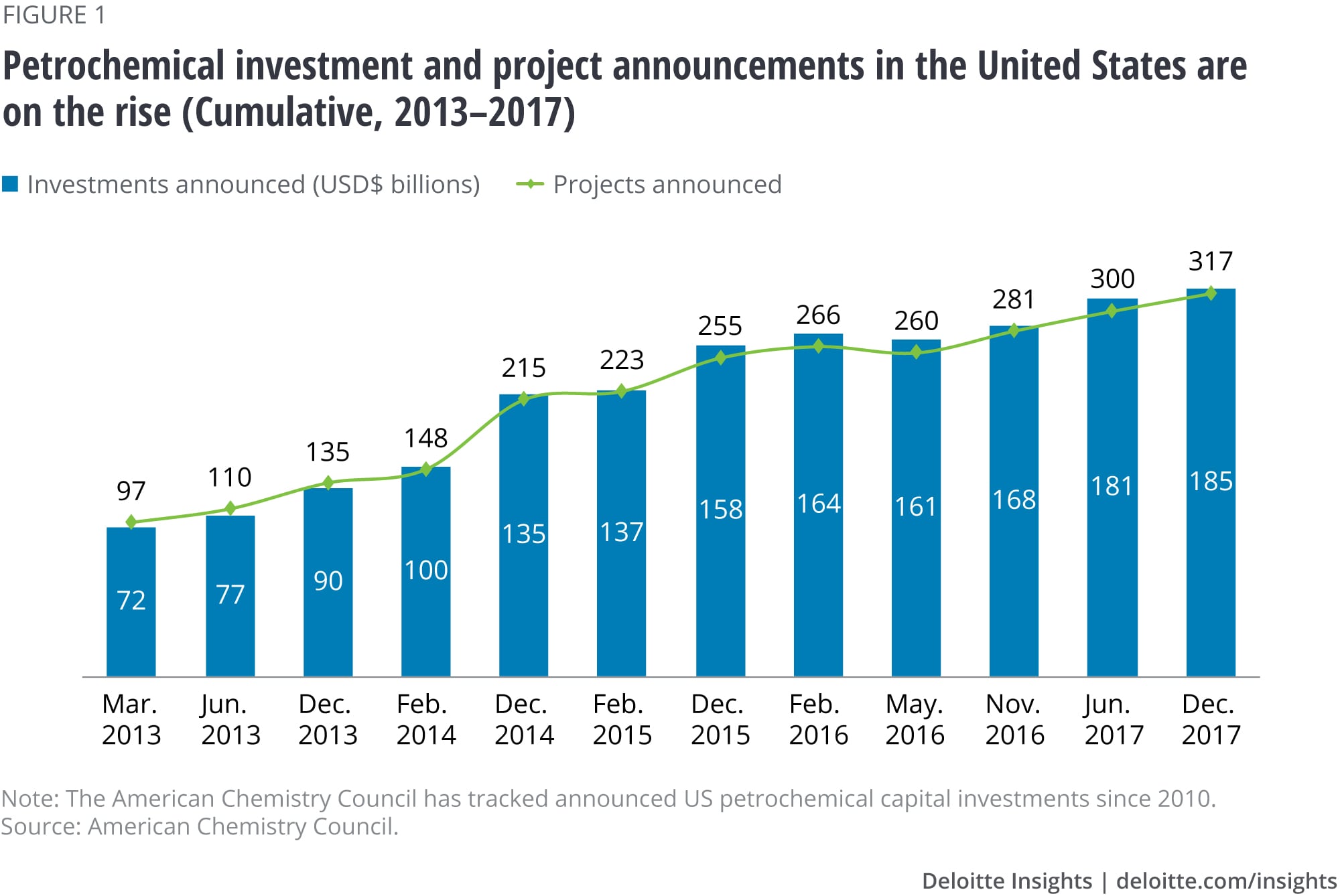

In the initial wave of investments, the US base chemical capital spending increased to US$15.3 billion from US$12.2 billion between 2008 and 2016.1 Between 2010 and 2017, availability of low-cost shale gas resulted in an unprecedented petrochemical capacity creation and expansion, primarily along the US Gulf Coast (figure 1). The region is set to see a similar uptick in the near future.2

According to a poll conducted by BIS Magazine in mid-2017, petrochemical executives agreed that a second wave of investments in the US petrochemical industry was imminent. At the same time, they agreed that its pace will likely be slower.3 Several uncertainties—including a narrowing oil-to-gas price spread, increasing exposure to key export markets, rising protectionism, and China’s emergence as a key producer and consumer of chemicals—could, however, obstruct these investments. Nonetheless, many executives are optimistic about the growth outlook.

Having said this, there will still be challenges for many companies trying to execute capital projects based on investments received during this second wave. The challenges could be similar to those faced during the first wave or quite different, perhaps even unique. For instance, during the first wave, not only did companies wrestle with on-time project completion, but projects frequently went overbudget. The economics may seem to have stacked up favorably at the beginning, but many projects were not structured to adapt to rapidly changing market conditions. Challenges such as high labor cost, low labor productivity, overly prescriptive or complicated stage-gate processes, complex governance models, inefficient decision-making, and cultural and team misalignment also led to poor execution.4 As a result, only US$89 billion worth capital projects, less than 50 percent of the announced US$185 billion, were either completed or under construction by end-2017.5

Outlook for petrochemical investments in other key regions

Across the globe, future demand and capacity growth look promising, but capacity buildup delays could result in higher capacity utilization. Among base chemicals, ethylene and propylene demand growth is likely to remain high, with global base chemical capacity forecasted to increase by more than 118 million metric tons (MMT) through 2022. This additional capacity growth will likely be led by Asia Pacific (primarily China), North America, and the Middle East.6

China is aggressively ramping up its base chemical capacity, with most of the additions relying on refinery-cracker complexes, followed by coal-to-olefins/methanol-to-olefins and propane dehydrogenation routes. A total of 6.9 MMT/year of ethylene capacity, along with about 5.0 MMT/ year of para-xylene (PX) capacity, is expected to enter China by 2021.7 Most of these capacity additions are driven by nonstate-owned enterprises (non-SOE), which are key producers of purified terephthalic acid/polyethylene terephthalate, and are short of key feedstocks (PX and monoethylene glycol). These upcoming new refinery-cracker complexes built by non-SOE players are aimed toward reducing fuel output and increasing petrochemical output. In another development, a multinational chemical giant has announced plans to build a wholly owned, integrated chemical complex in China, producing 1 MMT/year of ethylene, by 2026.8 Thus, given China’s increasing openness to foreign investments, both non-SOEs and multinational players are expected to build capacities in China.

In Europe, capacity additions are limited at best, given the region’s feedstock disadvantage and mature demand end-markets. However, some major chemical companies are considering expanding their base chemical as well as polyolefin capacities in Europe. For instance, a private multinational chemical company is considering site locations for setting up its 750 kt/year propylene plant.9 Another major producer of base chemicals is doing a feasibility study to expand its polypropylene capacity in Europe.10 In a similar vein, Dow Chemical has announced the construction of 450 kt/year polyolefin plant.11

The Middle East is no longer attracting as much petrochemical investments as before because investors see the United States and China as more favorable destinations.12 Nevertheless, base chemical capacity in the Middle East is still set to expand by 12 MMT during 2018–2022, with increasing reliance on mixed-feed crackers dependent on both natural gas liquids and naphtha.13 The key reason behind switching to mixed-feed crackers is to decrease the reliance on natural gas as a feedstock, to lower exposure to price fluctuations.

Barriers to successful project completion and how to overcome them

The first investment wave created a heated market for labor, equipment, and materials. With the second wave likely around the corner, companies and executives need to be prepared to identify the risks and appropriate hedging strategies, such as, using modularization to hedge against labor risk. In some cases, project contingency budgets and appropriate allowances for escalating costs may be in order. Evidently, about 50 percent of projects announced during the first wave failed to take off as planned. For petrochemical executives, there are lessons to be learned from this.

We have analyzed several projects that were started on the back of investments made during the first wave, and identified six potential roadblocks to successful project completion, why they possibly happened, and what executives can do differently this time around. Recognizing these barriers and their implications will help company executives plan and implement strategies to avoid a similar outcome.

Culture risk: Create a culture of openness and transparency

Team alignment and cultural fit are often sidelined during stage-gate reviews. As a result, problems of culture persist, and can affect performance and even project viability during the life cycle of a project. Often, project culture becomes toxic and dysfunctional in the execution phase, and project executives often alert their chain-of-command when only minimal time is left to mitigate the risk and sometimes when it’s too late.

Managing the cultural risks isn’t always easy because they are difficult to identify in the first place. Executives should focus on adopting a homogenous culture of communication right from the start of a project. A network-based culture focused on accurate alignment, cross-functional cohesion, and responsive people management can help create an ecosystem where individuals feel comfortable communicating project risks and issues. Routine culture assessments can go a long way in formally and informally addressing potential areas of risk in the reporting hierarchy.

Most capital-intensive projects are inherently prone to unanticipated external pressures over their lifetime. Openness and transparency as the norm mean that as such pressures arise, are proactive in identifying risks and soliciting a broader source of ideas and solutions across teams and experience levels in the organization. Providing regular assurance from all project layers creates a culture where members seek to resolve issues, and management neither punishes those who voice concerns nor rewards those who conceal problems. Instead, this culture rewards those who share potentially bad news, preempt challenges, and work to find ways around them.

Key considerations

- Is the project culture conducive to executing a successful project?

- Do project leaders feel comfortable reporting bad news to company executives?

Case study

An international energy company was developing a large-scale chemicals complex. The project was soon a year behind schedule and, in the rush to catch up, the project team went US$1 billion over budget. A quantitative analysis of the project team revealed a culture that managed for compliance, and not for results. Project levers were not balanced and the team was not clearly communicating their impact on the project timeline.14

The role of leadership in inducing and maintaining a culture of openness and transparent communication cannot be emphasized more. A culture that encouraged such tenets without the fear of repercussion—arising from either raising concerns or going over hierarchical constraints—could have averted the negative outcome.

Organizational misalignment: Design and define project incentives and responsibilities to drive the right behaviors

Undefined roles and responsibilities between operations and project functions result in confusion over the authority of managers and create unacceptable risks. For example, as the project progresses from scope development to implementation, project managers are unable to predict the pipeline of available skilled employees across the organization. Meanwhile, leadership is largely unaware of the objectives and goals of leaders in other departments.

It is important that leaders understand the risk of these blind spots and compensate where needed by referring to expert advice. A simplified reporting structure for operations and projects facilitates collaboration and increases efficiency—well-defined operating models, decision-making protocols, and delivery strategies ensure roles and responsibilities are clear among stakeholders, including the business, technical functions, and third parties. Within a project, investing in a capable owners’ team will position a project better for success. Projects with empowered and alert leaders have a better shot at success, owing to consistency of performance across the project life cycle.

Static performance management metrics become outdated as the project evolves. Implementation of clear, consistent, and balanced metrics can not only lead to focused attention of project leaders to pertinent issues, but also help in identifying affordable trade-offs and removing incentive bias. Those tracking third-party performance and accountability should consider the difference in the incentives for contractors and the owner organization.

Key considerations

- Do you have the most appropriate operating model for each phase of the project to optimize team alignment?

- Are incentives, priorities, objectives, and work practices designed to drive the desired behaviors?

Case study

A publicly traded, integrated oil and gas company sought to mitigate risk on a capital-investment project. It created an execution structure comprising third-party and internal resources. However, it failed to invest adequately in a capable owner’s team. A lack of clarity on the project’s operating model led to shared decision-making, which diluted the company’s ability to hold its third-party contractor accountable. Performance metrics focused on short-term compliance and did not adequately balance project levers, namely cost, schedule, and quality. Moreover, in an attempt to leverage the expertise of its leadership bench, the company rotated leaders. As a result, outcomes were difficult to manage.15This is a classic example of pitfalls of the failure to set up well-defined operating models, decision-making protocols, and delivery strategies.

Static business case: Constantly revisit the original business case to challenge project assumptions

During the first wave of investments, project economics was often favorable at the beginning. However, many projects were not designed to adapt to rapidly changing market conditions, and a cascade of unanticipated risks and delivery challenges followed.

Companies must be prepared to continually revisit the original business case assumptions and economic models. Dynamic and robust models and key assumptions updates help reflect the changing marketplace and projected returns. Risk mitigation strategies should be nimble and implemented quickly and effectively in response to changing conditions. However, executives must also know the walkaway (regret) costs and be ready to discuss this difficult decision.

Key considerations

Case study

Two years after launching the construction of a US$1 billion plant, an international chemicals company announced indefinite postponement of the project, citing raw material price volatility, continued market deceleration, and declining profit margins.

While companies often push past the final investment decision stage by adjusting estimates to make the economics look exciting, problems arise soon thereafter. This company, however, maintained a dynamic economic model with updated actual and forecasted costs, standing firmly on the target for the required rate of return and accurately measuring its walkaway cost. In the end, the company was able to accept the facts and flag the project as unviable, saving future costs. 16

Unnecessary competition: Strike the right balance between project owner’s and contractor’s responsibilities

On some petrochemical projects started on the back of investments received in the first wave, some owners recognized that they did not have the capacity or competency to execute a major project, so they extended their in-house team by retaining another engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) firm. While this is a common way for owners to supplement their in-house teams, sometimes the EPC that has been contracted to execute the project views the owner’s extended team as a competitor which can create tension and lack of transparency in sharing of information.

Companies can allocate appropriate resources and guidance to contractors, but it is in their interest to retain project ownership, particularly when it comes to critical functions, such as project controls, processes, reporting, and risk management. This enables them to exercise appropriate oversight and controls, and have clarity about project performance at any time.

Key considerations

- Do you have a contracting strategy that suits your requirements?

- Is the joint venture partner right for your project?

- Are contractors’ roles and responsibilities clearly defined?

- Are you retaining oversight and control of critical project-management functions?

- Have you tried implementing digital technologies such as blockchain to secure data infrastructure?

Case study

A chemical producer recently deferred new-plant construction due to cost overruns of more than US$1 billion. The engineering, procurement, construction, and management contract transferred major program management responsibility to the contractor, including full responsibility for critical areas such as project controls, process ownership, progress reporting, and risk management and mitigation. While a transfer of responsibility to contractors is not unusual, in this case, the company saw it as a way to downsize project management and assurance functions. However, this restricted its ability to monitor the contractor, control project performance, and gain a direct insight into project issues as they developed. Meanwhile, the contractor did not adequately staff up to handle its responsibilities on the project until long after the project had started. A combination of these led to cost and time overruns.17

Owners should retain an appropriate level of program management resources to monitor and control the project, even if they have transferred many responsibilities to the contractor. An additional layer of assurance provided by an independent third party can also provide valuable perspectives to hold both owner and contractor teams to account.

Unorganized project governance: Streamline governance and reporting to ease decision-making

Petrochemical investments and projects are typically expensive and complex, with total capital cost running in billions of dollars. Often, their project delivery structures resemble standalone company structures.

Unorganized governance and project structures lead to overly complex governance comprising multiple layers and steering committees, thereby causing inefficiencies and slowing decision-making. Streamlining governance and implementing standardized reporting mechanisms, including integrated information and key performance indicators, facilitate fast, efficient, and transparent decision-making, thereby saving significant time and costs.

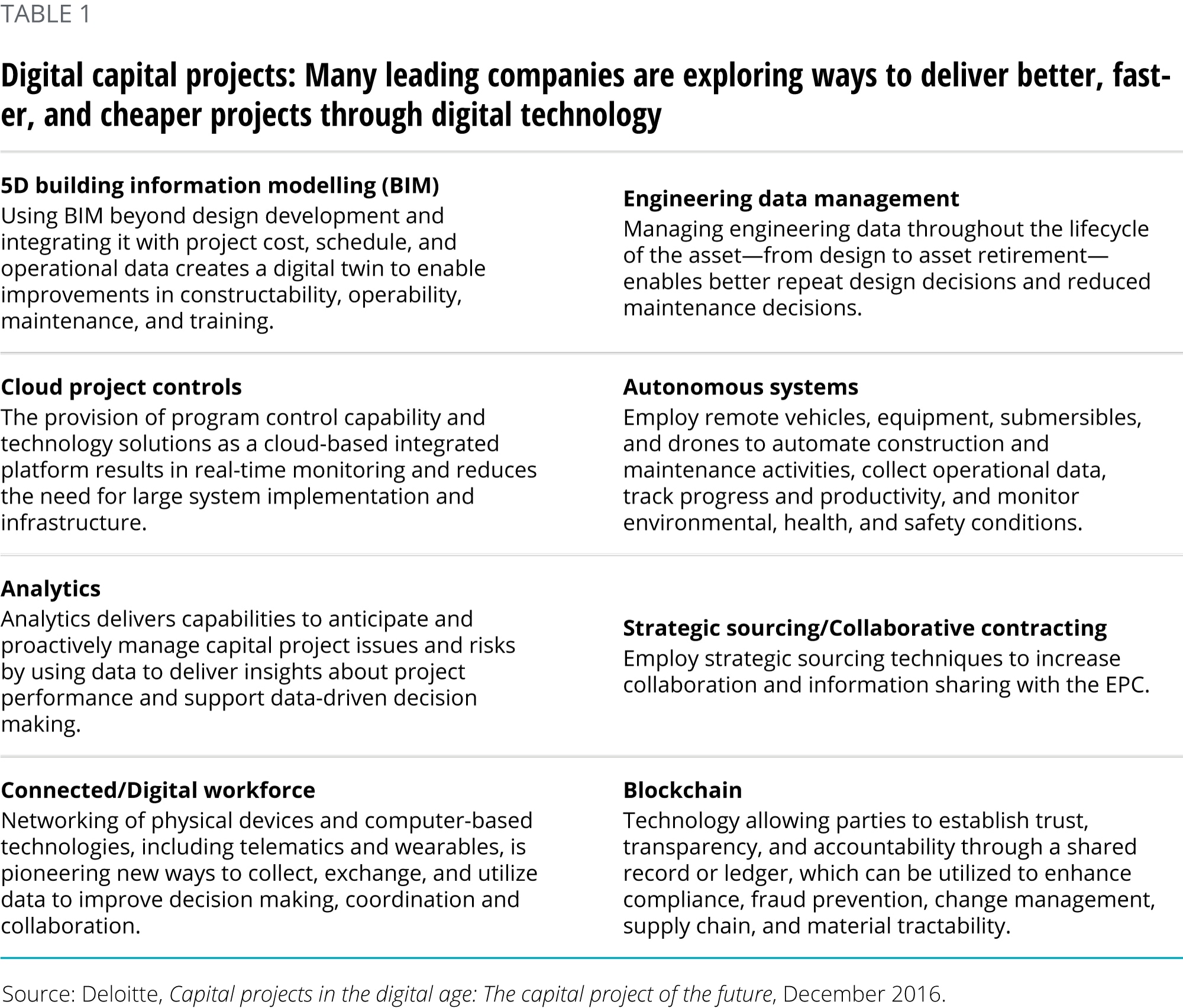

Digital and exponential technologies can play a prominent role in this regard (table 1). Predictive analytics can help rationalize governance structure and reduce the reaction time to external shocks. Drones can help collect construction-related data, track project progress, monitor changes in weather, and screen health and safety parameters. By leveraging platform-as-a-service, companies can potentially reduce capital expenditure, improve cost efficiency, and enable rapid scalability to meet the changing demands of a project.18

Key considerations

- Do you have a fit-for-purpose governance structure?

- Do the decision-makers have open and realistic discussions about project progress?

- Are decisions made quickly, and are they followed up adequately to ensure their effectiveness?

- Have you adopted digital and exponential technologies to facilitate accurate data capture and analysis?

Case study

An international energy and chemical company constructing a petrochemicals complex experienced a budget overrun of US$4 billion due to increased costs and schedule delays. Complex and inefficient governance and a lack of integrated project reporting between the owner and the EPC contractor were found to be contributing causes. Also, restricted information flow and complex reviews and approvals caused ineffective and slow decision-making by governing committees.19

The company could have streamlined the complex governance structure which would have led to faster and efficient decision-making. This would have also simplified the roles and responsibilities of team members, and ensured efficient flow of information and issues that need to be addressed, between the owner and EPC contractor.

Inadequate project reviews: Have independent specialists review stage-gate readiness

The stage-gate process provides a methodical, comprehensive procedure to review, approve, and drive projects through the major phases. But it can also create a “tunnel vision,” where a short-term view gets adopted. This perpetuates its own optimism, and reviews start to emphasize form over substance, ignoring critical risks (culture and team misalignment), and promoting bias (overly optimistic cost and time-to-delivery estimates).

Detailed and regular stage-gate readiness reviews by an independent—preferably external— assurance function ensure business-case adherence by challenging original project assumptions and establishing risk treatment and execution plans for the remaining stages. The findings and actions from these assessments should be shared with executive leadership and discussed during steering committee meetings while assessing project performance and making key decisions.

Key considerations

- Do you have a fit-for-purpose project assurance function independently monitoring the project?

- Are critical project elements, such as cost estimates, risks management, and stage-gate progression approvals, reviewed by third parties?

Case study

A project of a chemical producer had progressed from prefeasibility, through the final investment decision (FID), and into the execution phase when it started to become clear that the project was in trouble. There were multi-billion-dollar overruns and considerable schedule delays. A review revealed significant risk items that were shown as closed in the stage-gate review when in fact many of the risks had not been adequately mitigated. This, in addition to other issues, suggested that the review team was under pressure to close various open risk items prior to the project reaching FID.20

The company could have potentially avoided this situation by contracting a third-party assurance provider with reporting lines to ensure adequate independence from the project team.

Beyond traditional stage-gate reviews: What companies can do differently

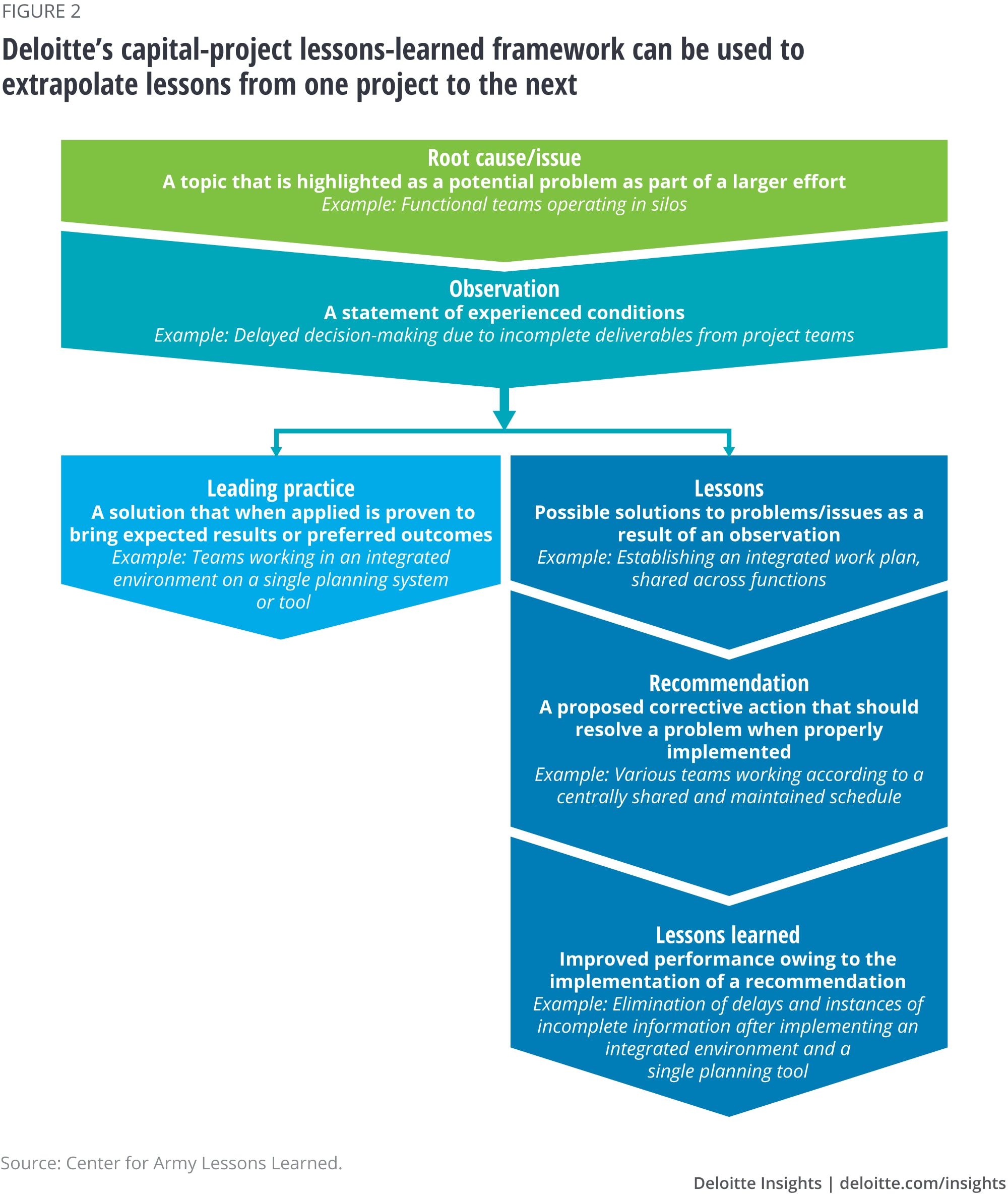

A critical step to avoid the costly mistakes of the past is to identify specific problem areas and take appropriate measures to manage them. This goes a step beyond the traditional stage-gate review process, where important problems and their root causes may be missed or overlooked, leaving new projects vulnerable to similar issues. This oversight is partly due to the reluctance of project teams to put failures on the record and as such a complete set of learnings from previous projects is not developed by the time the next project launches.

An easy solution is a “lessons-learned framework” and process (figure 2). Companies can define terminologies, processes, and key performance indicators to improve the performance of future projects. Given that a lesson is only a possible solution to a problem, companies will do well if they test all such possible solutions through recommendations or corrective actions. The process should be part of formal project management procedures, and issues identified should be presented transparently to create an environment where the project team feels comfortable sharing its observations.

Abundant and cost advantaged feedstock supply have many US companies considering—if not starting—major investments. As with the first wave, which began in 2010, the temptation to take advantage of these favorable conditions is likely considerable. As the case studies illustrate, many projects planned in the first wave of investments encountered many challenges, some foreseeable, others not. Similar challenges await many companies and project managers alike in the second wave of projects. However, this time the stakeholders will be likely better positioned and prepared in their planning and execution efforts on the back of the learnings from the first wave.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.