The real story of state and local workforces has been saved

The real story of state and local workforces How they have changed over the last decade

19 February 2014

Looking ahead, state and local governments are going to be making important decisions about the size, shape, composition, and cost of their workforces.

We often hear that the nation’s dismal employment situation is partly due to the loss of state and local government jobs. Now, with state and local tax revenues returning to normal and budgets coming out of the red, the situation is leveling—and in some cases reversing.

We thought it would be instructive to go beyond the typical snapshot analysis to look at this issue over a longer time horizon, so we analyzed data from the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the last decade.

Our goal was to assess key trends in state and local government employment: What caused the recent job losses? Have government salaries kept up with the private sector? Did rising salaries or rising headcount drive personnel costs over the past decade and a half? Has the demographic profile of the workforce shifted? Here is what we found.

Workforce reductions have come primarily through attrition, not layoffs

State and local governments shed more than 1 million jobs in the aftermath of the recession. Many analysts assumed that this reduction was due to recession-related layoffs. This is not entirely true.

The quits-to-discharges ratio is used to calculate the ratio of those who leave their jobs voluntarily to those who are forced out. In 2009, this ratio was 0.81 for states and localities and 0.79 for the private sector, indicating that more people were being forced out of their jobs than leaving voluntarily. By 2011, however, the quits-to-discharges ratio for state and local governments stood at 1.10, compared with 1.14 in the private sector, indicating that more people were quitting than being laid off.

Rather than layoffs, a failure to hire was a major cause of the total job losses in state and local government since 2009. The “hire-to-separation” rate, which must be above 1 for a sector to grow, was below 1 from 2009 to 2011 and just broke even in 2012, reaching 1.0061. This indicates that state and local government job losses were not primarily due to job losses but rather stemmed from letting vacant positions remain vacant.

Rising salaries, not headcount, largely drove higher personnel costs

Pay raises may have been few and far between for state and local workers in recent years, but over the long haul, they’ve more than held their own on the compensation front.

Since 1998, state and local workforces have grown almost as quickly as the underlying population (13 percent vs. 15 percent, respectively). However, state and local compensation growth has outstripped that of private sector salaries, rising by 51 percent during the period while private sector wages rose 33 percent. One reason for this has been the increasingly higher level of education required of civil servants. In aggregate, these changes increased the base cost of state and local employees by 70 percent.

That 51 percent rise in state and local salaries was driven by relatively even across-the-board increases across government functions. Apart from hospitals, where the average salary increase was 73 percent, none of the major state and local government functions nationwide had increases that deviated more than 9 percent from the overall average of 51 percent.

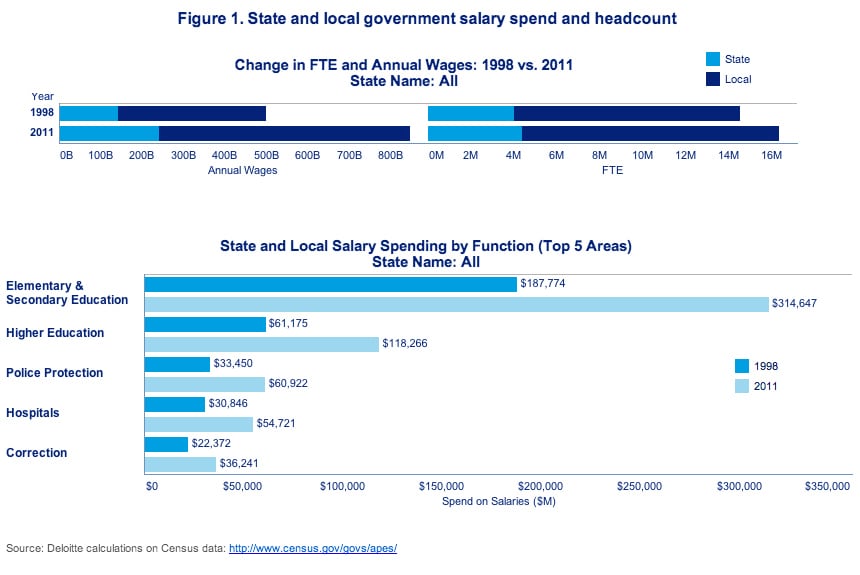

Education has dominated salary-spending growth since 1998

Elementary and secondary education has dominated state and local government salary expenditures, as well as the growth in spending, since 1998. Spending on salaries for K–12 is overwhelmingly local and grew from $188 billion in 1998 to $315 billion in 2011. During the same period, spending on salaries for public college and university employees rose from $61 billion to $118 billion. Figure 1 highlights the top five areas where spending on state and local salaries increased between 1998 and 2011; these two education line items represented 53 percent of the total change in spending.

The bottom line? State and local government personnel costs have increased over the past decade and a half primarily due to the rising per-capita cost of government employees, driven by across-the-board increases in salaries. More recently, during the fiscal crisis, state and local governments controlled their headcounts primarily through attrition rather than the widespread layoffs seen in the private sector. These actions, in turn, have impacted the overall age profile of state and local government workforces.

State and local government workforces have become notably older in the last decade

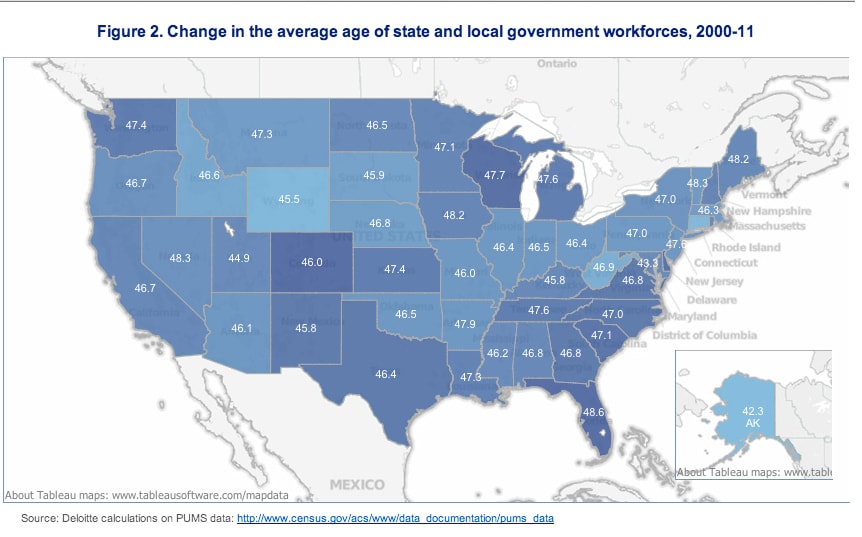

During 2000–11, the average age of a state or local employee increased from 44.7 to 46.9 years. This trend of aging can be seen across most states, with just a handful of exceptions in the District of Columbia, Alaska, Connecticut, and Wyoming (figure 2).

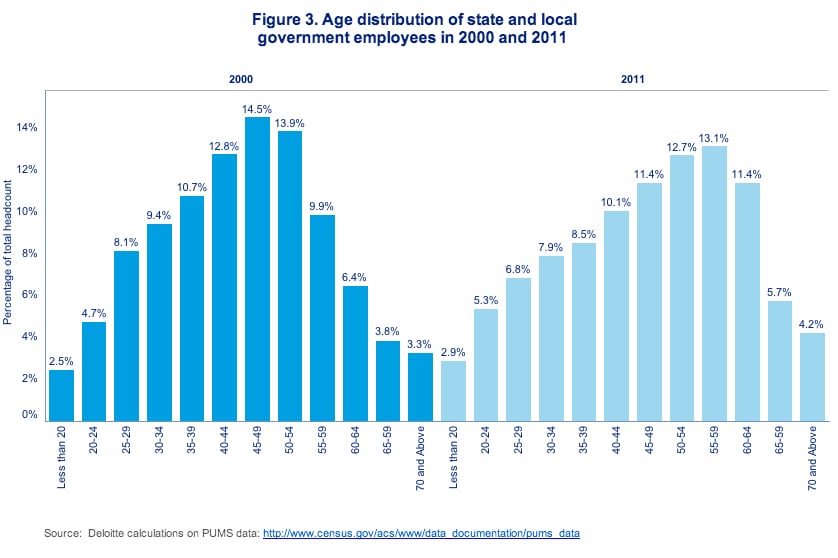

The combination of voluntary departures and hiring freezes appears to have disturbed a more or less “healthy” bell-shaped distribution of the workforce, which provided a mix of young and more experienced employees in 2000 (see figure 3). By 2011, 47 percent of the workforce was over the age of 50, and 55–59-year-old employees replaced 45–49-year-olds as the largest group.

State and local government workforces are disproportionately female

State and local government workforces exhibit a gender profile that runs counter to all other industry groups in the United States, including the federal government. In 2011, 60 percent of state and local government workforces were female, a level that has remained constant since 2000. Leading this trend are the southeastern states of Missouri, South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Arkansas—whose workforces are over 63 percent female.

That's the perspective of the past. Looking ahead, with government revenues on the upswing and Baby Boomers retiring (among other demographic challenges), governments are going to be making important decisions about the size, shape, composition, and cost of their workforces. It remains to be seen whether the past is prologue.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.