Going from good to great has been saved

Going from good to great Ways to make your sustainability report business-critical

09 July 2013

- Eric J. Hespenheide, Charles Alsdorf, Dr. Dinah A. Koehler

A solid sustainability report will be based on a body of meaningful, credible data and a determination of the materiality of ESG issues to the company’s strategy.

Overview

In 2011 nearly 6,000 organizations around the globe invested significant time and effort in monitoring and disclosing their sustainability performance, or ESG—environmental, social, and governance—performance, usually in a sustainability report that is separate from a financial statement.1 The steady increase in the volume of sustainability reporting over recent years, even by many well-known global companies, seems to indicate that many executive and governance leaders believe issuing a sustainability report is important. However, based on our discussions with hundreds of stakeholders on this subject, we also find a strong counter-current from various categories of stakeholders that question the value of ESG information as a basis for business and investment decisions.

The growing chorus of concerns suggests that sustainability reporting is at a crossroads. The choices are: Continue to collect, analyze, and communicate data that decision makers, investors, and customers may ignore, or create a reporting process that is more fully integrated into meaningful and substantive business and investment decisions—decisions that can impact value and competitive advantage. The key is to make ESG information more decision-relevant, including those decisions related to tracking, monitoring, performance evaluation, and incentives.

As we will discuss here, there are tremendous benefits that to be gained from improved ESG reporting:

- Attract investment into your company because the focus is on business-relevant information

- Direct how your company allocates capital and formulates its core business strategy

- Build and strengthen your company’s reputation and value proposition

- Address stakeholder concerns credibly

Companies that adopt a more robust methodology for determining ESG materiality can make sustainability reporting business-critical. In fact, we believe that the most effective way to successfully evaluate the materiality of ESG issues—and to truly derive business value from sustainability reporting—is to integrate them into the company’s overall business model, which drives its valuation.

Understanding the need for materiality in today’s environment

The questions raised by stakeholders—investors in particular—are not trivial. They may reveal a perceived credibility deficit both internally and externally:

- Internally, few managers are linking ESG issues to corporate strategy and value creation, creating a perception that the information is not useful.

- Externally, investors and other stakeholders ask whether the information is business-critical, and the lack of benchmark ESG metrics even within an industry raises the question as to whether ESG information can help them make better decisions.

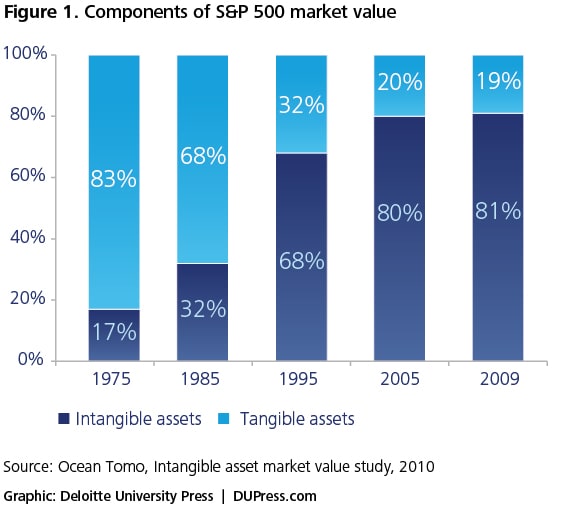

Transparency is a good thing—it can help reduce transaction costs, reduce a company’s cost of capital, and attract new capital to companies that demonstrate their ability to create future value.2 Today, investors pay more attention to a company’s intangible assets, because they are thought to account for 80 percent of its market value compared with tangible assets (see figure 1). Non-financial metrics used to measure intangible assets and liabilities help investors create a better picture of a company’s long-term organizational strategies to build intellectual capital, customer loyalty, sustainability risk management, and resilience in the face of rapidly shifting marketplace demands, among others.3 Yet most businesses are not very good at measuring these non-financial intangibles compared with traditional financial metrics that capture a company’s tangible short-term performance. It turns out the rewards for paying more attention to non-financial data, including ESG data, can be significant—it helps companies leverage up to 80 percent of their market value.

Most companies today select which ESG data to disclose based on their own intuition and experience, and one-on-one consultations with stakeholders or stakeholder panels (for example, customers, employees, suppliers, and communities). However, these methods do not help managers establish a relative ranking of ESG issues based on what matters most to the business, in part because these approaches do not often include senior leadership and are not quantitative enough. At its root the challenge is two-fold:

- Linking the management of ESG issues to the creation or protection of business value

- Balancing financial and non-financial data, especially when managers are accustomed to dealing with financial data on a daily basis, but have little experience with ESG issues, which tend to be measured in non-financial units or qualitative data

Can the conversation on sustainability reporting bring together sustainability managers and the CFO, controller, and other stakeholders central to measuring, evaluating, and investing in the business’s long-term growth strategy? Yes, if the information is:

- Aligned with the business’s strategic objectives

- Understood as part of the value proposition for various investment projects

- Incorporated into the assessment of how various projects are evaluated

- Effectively communicated with a direct linkage to the business’s strategic objectives

By applying the principle of materiality the focus will be on fewer ESG disclosures and the link to valuation will be made more explicit. The principle is well established in traditional financial reporting and emphasizes how information can change the way its users assess a business’s performance and growth prospects. According to the SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin 99, a matter is “material” if “there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person would consider it important.” Financial management and the auditor must consider both quantitative and qualitative factors in assessing an item’s materiality.4

Materiality can help with ESG metric selection because it:

- Imposes a disciplined approach to focusing on data that is useful for business and investment decisions

- Helps companies focus the ESG information disclosed on that which is business-critical

- Can improve the flow of capital to those companies that limit the negative social and environmental impacts of their business activities and improve their prospects for future value generation

Currently, a variety of global and US-specific initiatives are under way to bring more clarity on which key performance indicators (KPIs) should be disclosed within the next three to five years (See accompanying sidebar: “Major reporting efforts under way”). In the meantime, we suggest an approach that builds on multi-stakeholder engagement processes used by many companies today—one that places the organization’s business objectives at the core of the reporting process right at the start of an ESG materiality assessment.

Major reporting efforts under way

The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was launched in 1999 and has produced several iterations of a voluntary sustainability reporting framework for disclosure on key areas of economic, environmental, social, and governance performance. The network is currently working on the G4 Guidelines, which are to be launched in 2013. G4 puts much greater emphasis on materiality determination as part of the disclosure process.

The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) was launched in May 2002 by 35 institutional investors representing assets in excess of $4.5 trillion, who wrote to the chairmen of the FT500 Global Index companies asking for investment-relevant information relating to greenhouse gas mitigation. The first annual report came out in 2003, and today, industry-, country-, and city-level reports are issued, in addition to CDP water disclosure launched in 2009. The CDP has become the de facto standard for voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions and risks, including supply chain risks.

The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), founded in 2010, is developing a framework for integrated reporting that demonstrates the linkages between an organization’s strategy, governance, and financial performance and the social, environmental, and economic context within which it operates in a clear, concise, consistent, and comparable format. IIRC issued a discussion paper in September 2011 describing the rationale for integrated reporting, and offered an initial proposal for the development of an international integrated reporting framework. An outline of the framework was released in July 2012. It expects to release a first version of the framework in late 2013. The council continues to develop the framework, which will include guidance on how to determine materiality, and is working with 70 pilot companies on the implementation of the framework.

Modeled on the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), launched in 2011, collaborates with regulatory and accounting organizations (for example, the SEC, Center for Audit Quality, PCAOB) to aid in the development and dissemination of a set of industry-specific sustainability reporting standards for disclosure in standard filings such as Form 10-K. The SASB plans to identify which sustainability issues are material for industries to establish a minimum disclosure standard that is concise, comparable within an industry, and relevant to all 35,000 publicly listed companies in the United States. The SASB plans to issue a complete set of standards covering all 10 sectors and 102 industries by 2015.

The Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings (GISR) was launched in June 2011 to design and implement a global sustainability ratings standard and to move existing sustainability ratings toward a core set of principles, processes, and performance. Fostering convergence and harmonization across ratings will enhance the quality and comparability of material information needed to move markets toward more sustainable outcomes. The group seeks to develop this framework within the next two years.

Making the link between ESG issues and corporate strategy

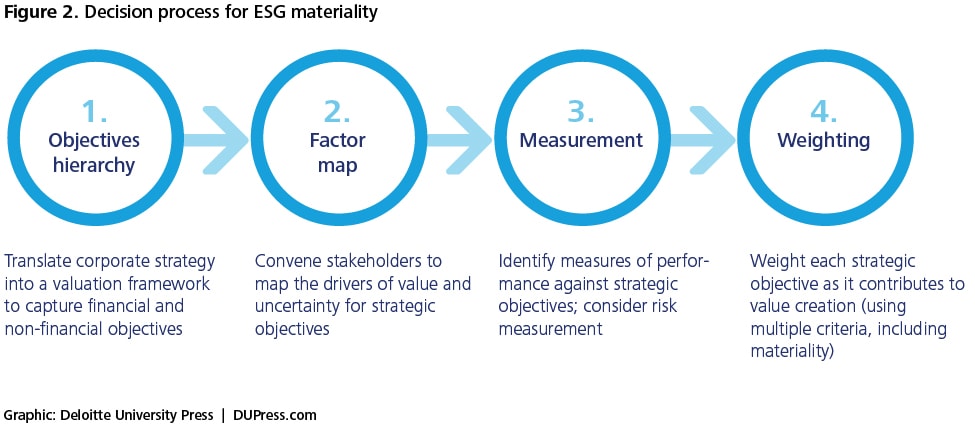

Business-critical in ESG reporting depends primarily on how the organization engages with its stakeholders (internal and external) to determine which ESG issues are most material and then focusing their efforts on them. Managers and investors need a practical way to evaluate a company’s ability to create direct tangible and strategic intangible value in a consistent, defensible, and less biased manner. Luckily, well-established decision support tools widely used to navigate difficult decisions can be leveraged here to analyze ESG materiality tied to an organization’s objectives, as shown in figure 2.

Step 1—Translate corporate strategy into a valuation framework to capture financial and non-financial objectives

A key first step in structuring any business decision is to understand the organization’s most strategic objectives and answer the “what do we want” question—which is unique to each organization. Strategic objectives need not be limited to financial outcomes. They can include non-financial outcomes, such as market share, supplier relationships, energy efficiency, stakeholder expectations, brand equity, and worker health and safety. The goal is to identify the organization’s objectives comprehensively, while making sure they do not overlap. The objectives, once articulated, can be structured in a hierarchy, which makes relationships among them explicit, as shown in the example in figure 3.

The objectives hierarchy can have several levels beyond what is shown here, which is an illustrative example adapted from a government agency. For instance, the “Minimize energy and H2O consumption” objective can depend on the amount of electricity usage, the water-intensiveness of production, and CO2 equivalents saved, which, in turn, is a function of the composition of power production in the local utility. Once the hierarchy is completed, stakeholders need to identify which objectives are key, that is, strategic, in order to maximize value. In other words, focus on those areas where information is most likely to be material to the company.

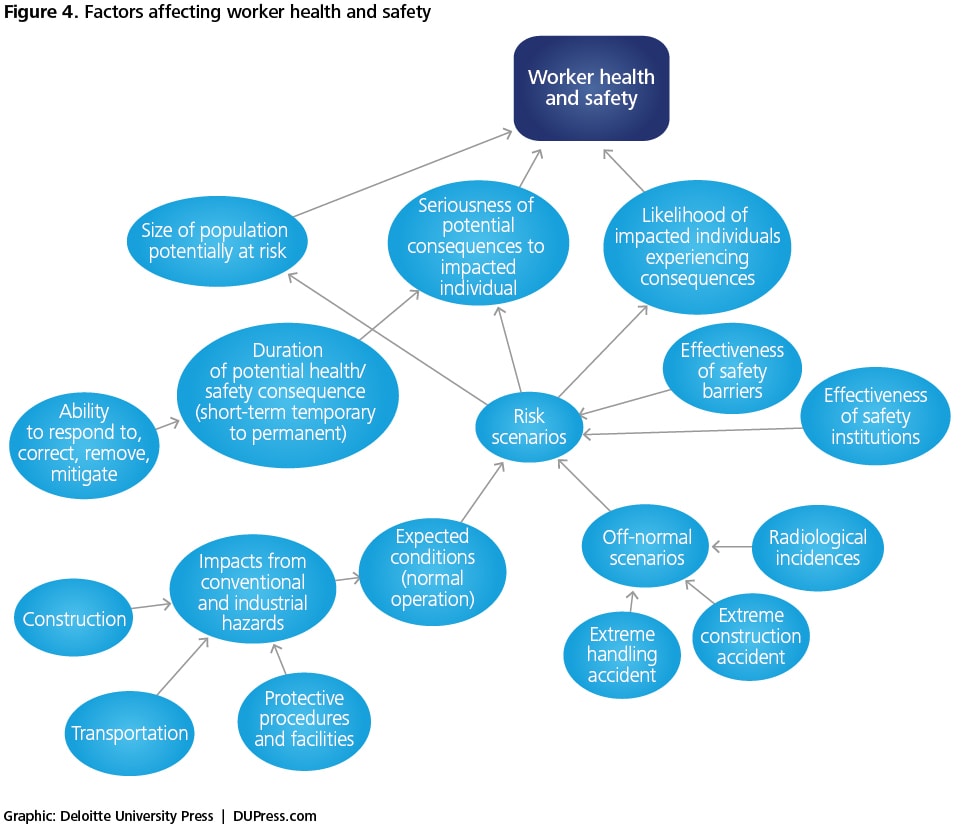

Step 2—Convene stakeholders to map the drivers of value and uncertainty for strategic objectives

The success of each strategic objective depends on multiple drivers (or factors), as we show with the worker health and safety example in figure 4. Many ESG factors are interdependent, and understanding how they drive value is fraught with uncertainty. However, many managers know intuitively that the impact on value can be significant and based on experience, understand that incidents and accidents can be costly, cause business disruption, and deplete employee morale. Without a strong safety culture and management processes, companies can put their future financial value at risk.

Step 3—Identify measures of performance against strategic objectives and consider risk measurement

Identifying performance measures is as important as mapping out the drivers of a company’s value and future success. This means identifying performance measures for each strategic objective (whether financial or non-financial). A company’s value is based on direct or tangible value, such as assets in place and direct financial costs and benefits from operations. Even though managers have more experience measuring direct value, they often struggle with forecasting how key risks and uncertainties might impact future performance, or how they can ensure defensible, consistent, financial assumptions across various scenarios, including how ESG factors impact these scenarios.

In addition, value can also be created indirectly, but still be key to future growth. This includes strategic decisions on the company’s managerial flexibility, system reliability, brand value, innovation, impact on the environment, improved health and safety, and customer satisfaction. Creating this more strategic value is particularly appealing to investors who seek out companies with strong future growth potential and high intangible asset value. Strategic value is hard to measure, but there are ways to measure performance as it relates to value. Some objectives can be described through quantitative models and observable metrics, such as, the number of new customers, customer contacts, and web visits. Others, where data is missing, may be measured using proxy data. Yet others may need to be modeled, for instance, by developing a high-to-low, five- or seven-point scoring scale that is constructed with input from the multi-stakeholder team.

Step 4—Weight each strategic objective

The next step—weighting—is crucial to the integration of ESG issues into the company’s business model and core business decisions and approach to disclosure. Building on the first three steps, which help frame the business’s strategic objectives, managers are now better positioned to create a complete picture of the company’s ability to achieve its performance objectives and invest in future growth. This is where many management teams tend to fail, because they do not use a structured approach to understanding how multiple objectives jointly link into value creation and which have the greatest potential to generate value, that is, what to weight the most.

This can be particularly vexing for sustainability managers, who watch their sustainability objectives fall by the wayside; they often have not been properly considered in the context of the company’s business model. A structured multi-stakeholder workshop employing decision support tools can assign weights to each objective to “quantify” strategic benefits, using multiple criteria that include materiality, and to enable comparing and ranking of the ESG issues the company faces.

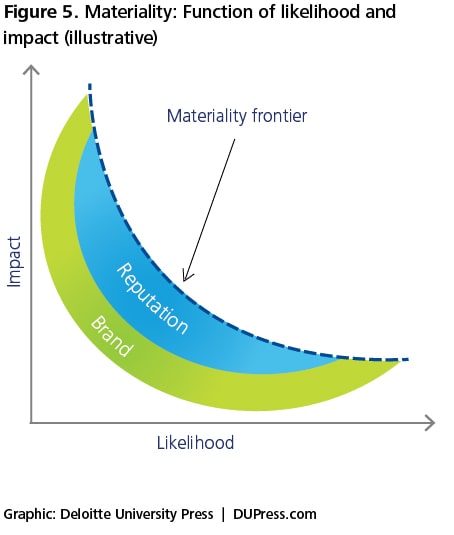

Materiality pertains to those ESG issues that can impact company valuation.5 For example, ESG issues can become material due to internal/external stakeholder actions driven, in part, by how they perceive whether a company is destroying or creating value. Some ESG issues will likely affect a company’s bottom line in a given time frame (1–5 years) due to factors such as business interruption, consumer boycotts, regulation, or license to operate. These may lie on or above a materiality frontier. Beyond the likelihood of direct financial impact, strategic intangible value (for example, brand and reputation) could also be affected, which may not be an immediate threat to a company’s cash flow but may affect enterprise value due to anticipated future cash flow impacts. Therefore, for those companies with a strategic objective of building a strong reputation and/or brand, certain ESG issues should be carefully evaluated in materiality determination, even if these impacts fall below the materiality frontier (see figure 5).

After this crucial mapping exercise, managers are in a much better position to construct a comprehensive view of the company’s ability to create both direct and strategic future value, including those ESG issues deemed material to business value. Specifically, managers can now run decisions through this framework to help them identify those actions and investments that are expected to generate the most value to the company and its stakeholders, because all aspects—including ESG issues—have been considered.

Assessing an organization’s state of readiness

Getting to a more strategic view of ESG performance depends on the maturity of an organization’s sustainability program and its goals, its measurement system, and whether the organization wants to understand the impact of ESG performance on its valuation. Evidence is growing that stakeholders drive ESG performance and can affect financial valuation in the near term.6 Furthermore, a company’s ESG strategy can create long-term business value—value not only to senior executives but also to shareholders who seek to identify companies that are committed to creating long-term value.

While sustainability reporting is expanding around the world, many companies do not issue a report or are just starting to consider doing so. Beginners and intermediate companies may only meet the basic expectations for disclosure and are often criticized for their lack of transparency. Many do collect data related to compliance with regulations (for example, environment, health, and safety laws), but fail to proactively engage with their (non-regulatory) stakeholders. Such an ad hoc, reactive stance often forces these companies to adopt a crisis management approach to various external pressures from activist stakeholders, including protests at their suppliers’ facilities, boycotts, and shareholder resolutions. In each instance, the company risks negative impacts on its stock price. When external stakeholders demand ESG information, it must be collected on an issue-by-issue basis or sourced from readily available data and is not necessarily business-critical.

Companies with more mature ESG reporting capabilities have a better understanding of how their actions can impact their stakeholders and engage more proactively with them to find solutions. Through continuous engagement with a handful of stakeholders, these companies start to manage ESG risks and integrate ESG information into business decisions. These organizations use the GRI guidelines to decide what information they will disclose in their sustainability report and will solicit third-party review of their report, for example, limited assurance.

Figure 6 illustrates the actions that an organization can pursue as it develops a more mature and forward-looking approach to a sustainability reporting process that is more integrated into how it creates value. No longer an ad hoc, externally focused exercise, identification of ESG KPIs is more concerned with what is likely to be material to the company in the near and long term. Sustainability managers may work to bring together stakeholder panels, and some use surveys to capture the concerns of many more stakeholders. These leading companies undertake materiality determination and include a materiality matrix in their reports. These companies are making the transition from ESG risk management to value creation through effective ESG data management and are taking practical steps within their companies to integrate ESG information into business decisions.

Finally, companies that strive to link sustainability reporting with business value are focused on how ESG measurement and management can contribute to future growth. They see sustainability as a source of innovation and competitive advantage and want to integrate it into their core business strategy. For these managers, alignment of financial and non-financial information with the company’s key objectives is critical to optimizing performance and future growth. The time spent in analyzing those alignments can also bring future dividends on ESG dimensions, because those that are deemed material are stronger candidates for investment. Once ESG issues are integrated into resource allocation decisions, stakeholders, and especially shareholders, can be more confident that sustainability considerations are part of the company’s core business strategy.

Conclusion

Effective sustainability reporting should describe what the company is doing for its shareholders and its other key stakeholders by linking actions and results to the organization’s objectives. A solid sustainability report, therefore, will be based on a body of meaningful credible data—quantified and tracked—and a determination of the materiality of ESG issues to the company’s strategy. This bottom-up approach helps managers demonstrate that they have a solid process that has considered the entire organization’s operations, key business partnerships, and stakeholder expectations. As with financial reporting, where a company is obligated to capture 100 percent of its financial transactions, ESG reporting needs to identify all potential risks that could result in a current or future financial impact.

In summary, there are several important benefits of the more robust ESG materiality determination process described in this paper, including those that help achieve:

- Improvements to the quality, defensibility, and confidence of decisions regarding ESG disclosure

- Measurable strategic value and more efficient use of resources

- Integration with other systems and data sources

- Improvements in stakeholder engagement and organizational alignment

- Education of the organization with regard to effective ESG management