The return of consumer debt: Increasing interest rates may reveal some cracks in the system Behind the Numbers, March 2018

26 March 2018

Patricia Buckley

Patricia Buckley

Consumer debt is popular again. A decade after households paid down (or defaulted on) debt after the Great Recession, borrowing is back—and it’s now above the prior peak of 2008. That high level of debt may pose some risks for the economy.

Introduction

Rising levels of debt is not necessarily a negative development. Rather it could indicate optimism about the future—households are confident enough in their economic situation to commit to purchase today goods and services such as clothing, furniture or restaurant meals that they will pay for in the future as their credit card bills become due. But are they factoring in the possibility that interest rates on those prior purchases are on the way up? And what will happen to future purchases of autos and education? While the interest rates are fixed for current auto and student loans, new purchases of autos and additional years of education will likely come at a higher cost through higher interest rates.

At the beginning of 2016, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve Board began a slow, measured process of moving the federal funds rates target from near zero (0.25 percent). Since that first quarter-point increase, the FOMC has raised the rate five times, most recently in December 2017, and the federal funds rate currently stands at 1.5 percent. Our current Deloitte forecast for the US economy has the FOMC raising rates four times during 2018, which would have the federal funds rate ending 2018 at 2.5 percent.

While longer-term rates, such as 30-year mortgages, do not immediately react to movements in the federal funds rate, rates for shorter-term loans, such as auto, credit card, student, and home equity lines of credit—rates that are often tied to the prime rate—do react quickly. The prime rate is closely tied to the federal funds rate, usually with a 3 percentage point differential. Given our forecast for the federal funds rate, this implies that the current 4.5 percent prime rate will likely rise to 5.5 percent by the end of the year, and with it rates for all types of consumer debt tied to the prime will also rise.

Composition of household debt

Household debt peaked during the middle of the recession (mid 2008) at $12.7 trillion. It then fell to $11.2 trillion in the second quarter of 2013. From that low point, debt outstanding began a slow rise, passing the previous peak at the beginning of 2017. It currently stands at $13.1 trillion (figure 1). During the nine-year interval between peaks, the composition of household debt shifted, with the proportion of mortgage debt falling from 73.3 percent in 2008 to 67.6 percent in 2017 (a decline of over $400 billion) and the proportion and the dollar value of student and auto loans rising. Student loans rose from 4.8 percent to 10.5 percent of total debt or from approximately $600 billion to $1.4 trillion and auto loans rose from 6.4 percent to 9.3 percent of total debt or $800 billion to $1.2 trillion. The other loan categories—credit cards, home equity lines of credit, and “other”—showed much less change.1

Mortgage debt

The decline in mortgage debt corresponds to a decline in homeownership rates. Between the third quarter of 2008 and fourth quarter of 2017, the percent of occupied housing units that were owner occupied fell from 67.9 percent to 64.2 percent.2 Similarly (although exactly matching dates are not available) between 2007 and 2016, the percentage of households with a primary residence as an asset fell from 68.6 percent to 63.7 percent, and the percentage of households with debt secured by a primary residence fell from 48.7 percent to 41.9 percent.3

Even as the total dollar amount of mortgage debt and the proportion of households with mortgage debt declined, the credit worthiness of those seeking new mortgages has been increasing and delinquencies have been declining (figure 2). A full 8.8 percent of the $394 billion in mortgage originations from the third quarter of 2008 went to borrowers with a credit score of less than 620 and an additional 7.2 percent went to those with only a slightly better credit score (620–659). Just 35.9 percent of mortgage dollars went to the most creditworthy―those with a credit score of over 760. In contrast, in the fourth quarter of 2017, well over half of the dollar value of the $451 billion in mortgage originations went to those with very high credit scores (56.8 percent) and only 9.7 percent went to the two lowest credit score groups. Although the value of mortgage originations going to the least creditworthy is up slightly from the very low levels of 2011–2013, there is no indication of an acceleration in subprime lending.

After several years of higher-quality loans and a recovery in housing prices, mortgage delinquencies are also down. After peaking with almost 9 percent of balances being at least 90 days delinquent in 2010, the delinquency rate for home mortgages is now just 1.3 percent and continuing to trend down.4

The mortgage market is somewhat insulated from movements in short-term interest rates because of the dominance of long-term financing. In 2016, approximately 90 percent of homebuyers chose a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage with only 6 percent choosing a 15-year fixed-rate mortgage, 2 percent choosing an adjustable rate mortgage, and the remaining 2 percent picking another type of loan.5

However, as the markets factor in higher future interest rates into their 30-year rates, mortgage interest rates will likely begin to rise. This increase in the cost of homeownership could exacerbate the trend of falling homeownership rates. Since mortgage rates have already begun to creep up with the rise in inflation expectations, we are already seeing its impact on home affordability. Between 2016 and 2017, slightly higher mortgage rates (from an average of 3.88 percent to 4.20 percent) combined with home prices rising faster than income, to reduce home affordability as measured by the National Association of Realtors’ Housing Affordability Index.6

Student loans

Student loans have grown very quickly. Between the third quarter of 2008 and the fourth quarter of 2017, the dollar value of student loan debt more than doubled to $1.4 trillion, which pushed it up to the second-largest category of household debt (figure 1). According to the National Center for Education Statistics, almost half of all full-time, first-time degree/certificate-seeking undergraduate students enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions in 2012–13 had taken out a student loan.7

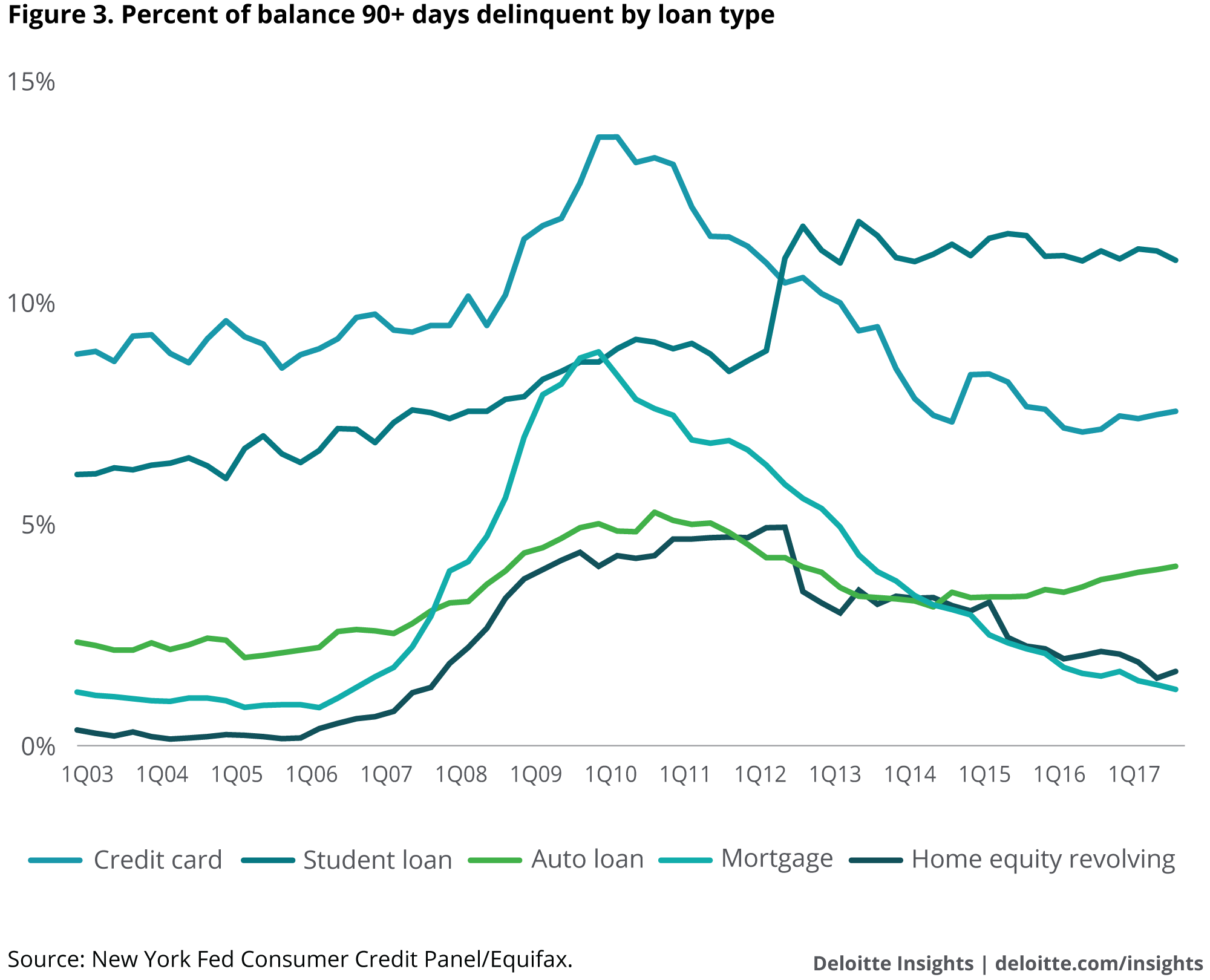

A major issue with student loans is the high delinquency rate—the highest of any type of household debt category—as shown in figure 3. The 90+ day delinquency rate has been at or above 11 percent since the middle of 2012.

Most student loans are guaranteed by the federal government with an interest rate set by Congress that is tied to the 10-year Treasury rate. While the interest rate is fixed for the life of these loans, interest rates on new loans vary with each new school year. For example, a direct subsidized undergraduate loan originated in the 2007–2008 school year carried an interest rate of 6.8 percent. By the 2011–2012 school year, that rate dropped to 3.4 percent. The current rate for this type of loan is 4.45 percent.8 There is a Congressional cap on student loan interest rates of 8.25 percent for undergraduate loans, which leaves just under 4 percentage points that these loans can rise—a jump that could adversely affect future ability to finance education.9

Auto loans

Total vehicle sales at the end of 2017 stood at 17.6 million, just below the all-time 2016 peak of 17.9 million10 and consumer borrowing for auto loans rose to support this high level of sales. The current portfolio of auto loans equals $1.2 trillion, just trailing student loan category in size. Even with high sales and a growing amount of auto debt, the proportion of households that own a car has been falling. In 2007, 87.0 percent of households had at least one car, but that proportion had dropped to 85.2 percent by 2016. The decline has been widespread across most income and age categories of households.11

While the delinquency rates for these loans began to subside after peaking at 5.3 percent in late 2010, they began to rise again in 2014 (figure 3). Recent research from the New York Federal Reserve Board using unpublished data finds that the uptick in delinquencies is largely attributable to loans made by auto finance companies, which dominate the subprime auto lending market—originating and holding more than 70 percent of subprime auto loans. Banks and credit unions are much less likely to issue loans to subprime borrowers and of those they do lend to, the borrowers are less likely to become delinquent.12

Experian estimates that 85.1 percent of new cars and 53.8 percent of used cars are financed.13 While holders of existing auto loans will not be impacted by future interest rate rises, future purchasers will likely see higher rates, a factor that might slow future car sales.

Looking forward

The two other debt categories not discussed in detail here will likely immediately feel the rise in interest rates. Credit cards and home equity lines of credit generally have variable interest rates. Approximately 44 percent of households carried credit card balances in 2017, a decrease from 46 percent in 2007.14

Since the recession, overall household leverage (measured as the ratio of debt to annual income) has improved, falling from 14.8 percent in 2007 to 12.2 percent in 2016.15 However, leverage ratios are up for the poorest and the youngest households. The average leverage ratio of households in the bottom 20th income percentile rose from 13.3 percent in 2007 to 17.8 percent in 2016 and for households headed by someone 35 years or younger, leverage ratios are up from 44.3 percent (2007) to 47.0 percent (2016).

With rising interest rates causing payments to credit card companies on prior purchases to increase and making future credit card and auto purchases more expensive—as well as raising the cost for future student loans, there is a possibility that the rates will slow the economy. Since the last slowdown had a disproportionally large negative impact on the poorest and the youngest households,16 we could see delinquencies rise across all debt types, even as the rate of consumer spending slows.