A new view of international trade has been saved

A new view of international trade Issues by the Numbers, March 2014

18 March 2014

Patricia Buckley

Patricia Buckley

A fresh take on the numbers suggests that the United States’ international trade position is stronger than widely assumed.

View the related infographic.

The United States is in the process of negotiating two major regional trade and investment agreements that together cover a majority of our export dollars, including 61 percent of our merchandise exports1—the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP). If these agreements live up to their promise, they would substantially enhance the benefits that the United States derives from trade. The potential of these agreements to generate jobs and growth in the United States is clearer if one considers some new data constructed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). These data look at trade in value-added terms rather that the gross-flow basis generally published by national statistical agencies. Three aspects of US trade not particularly visible in the gross-flow data, but that stand out quite clearly in the value-added data, are:

- The relative strength of the US export sector is higher than is generally understood, and some of our larger bilateral deficits, particularly with China, may be overstated

- US trade is well integrated into global value chains, which can be a powerful source of increased efficiency and firm competitiveness

- The US service sector plays a significant role in exports, especially when considered on a value-added basis

Each of these commonly underestimated strengths could be further enhanced if the goals of the TPP and T-TIP are realized.

The trade deals now under negotiation are the largest in scope ever attempted outside of the multilateral framework of the WTO and the most ambitious and extensive, in terms of coverage, that the United States has ever envisioned.

A new generation of trade deals

The trade deals now under negotiation are the largest in scope ever attempted outside of the multilateral framework of the WTO and the most ambitious and extensive, in terms of coverage, that the United States has ever envisioned.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership. Starting with nine countries in 2011 (Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States), the TPP has expanded to include Japan, Canada, and Mexico. This expansion is consistent with the TPP’s stated purpose to be a “living” agreement that sets a trading framework that will eventually expand to cover additional Pacific Rim nations.

The original set of trade ministers identified five defining goals that they felt would make TPP “a landmark 21st-century trade agreement, setting a new standard for global trade and addressing next-generation issues that will boost the competitiveness of TPP countries in the global economy.”2 These goals, which are aimed at creating jobs, raising living standards, improving welfare, and promoting sustainable growth in the participating countries, are:

- To provide comprehensive market access, eliminating tariffs and other barriers to trade and investment in goods and services so as to create new opportunities for workers and businesses and immediate benefits for consumers

- To develop a fully regional agreement to facilitate the development of production and supply chains among TPP members

- To address cross-cutting issues (regulatory coherence, competitiveness and business facilitation, small- and medium-sized enterprises, and development) to support economic integration and increase trade and investment

- To address new trade challenges to promote trade and investment in innovative products and services, including those related to the digital economy and green technologies

- To create a living agreement to enable the updating of the agreement as appropriate to address trade issues that emerge in the future as well as new issues that arise with the expansion of the agreement to include new countries3

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. The purpose of the T-TIP is to further open European Union (EU) markets, increasing the $458 billion in goods and private services the United States exported in 2012 to the European Union (the United States’ largest export market) and strengthening rules-based investment to grow the world’s largest investment relationship.4 The United States and the European Union already maintain a total of nearly $3.7 trillion in investment in each other’s economies (as of 2011).5 The goals of the T-TIP include:

- Eliminating all tariffs on trade

- Tackling costly “behind the border” non-tariff barriers that impede the flow of goods, including agricultural goods

- Obtaining improved market access on trade in services

- Significantly reducing the cost of differences in regulations and standards by promoting greater compatibility, transparency, and cooperation, while maintaining high levels of health, safety, and environmental protection

- Developing rules, principles, and new modes of cooperation on issues of global concern, including intellectual property and market-based disciplines addressing state-owned enterprises and discriminatory localization barriers to trade

- Promoting the global competitiveness of small- and medium-sized enterprises6

A new generation of trade data

Most countries, such as the United States, gather and publish trade data based on gross flows. Not only do such measurements overstate the total value of trade, but they may distort individual countries’ benefits from trade as well. The joint OECD-WTO “Trade in Value-Added” (TiVA) initiative seeks to remedy this shortcoming by constructing a series of metrics that accounts for the fact that goods and services, although sold in their final form by a particular country, are composed of inputs from various countries around the world. TiVA’s indicators address this issue by measuring the value added by each country in the production of goods and services that are consumed worldwide. These indicators are designed to provide new—and more meaningful—insights into the commercial relations between nations.7 In some cases, they change our view of reality.

The United States’ trade situation in perspective

Over time, production has become increasingly geographically fragmented, with materials and components crossing many borders on their way to becoming final goods and services. The gross flows of exports and imports presented in official US monthly trade statistics count the total value of each good or service every time it crosses US borders. The new OECD/WTO data allow for the disaggregation of trade flows into where the value is created.

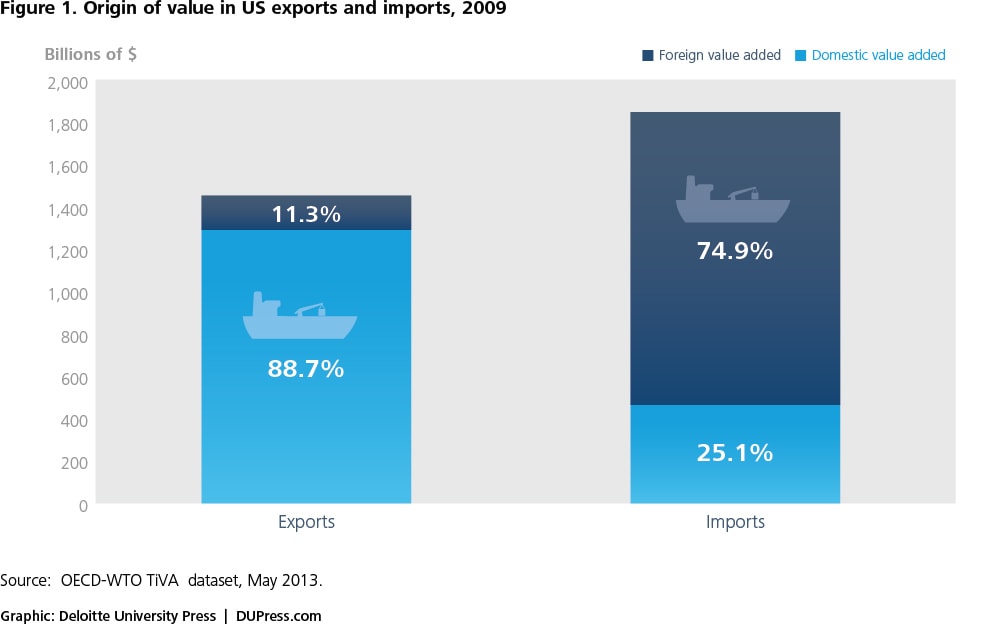

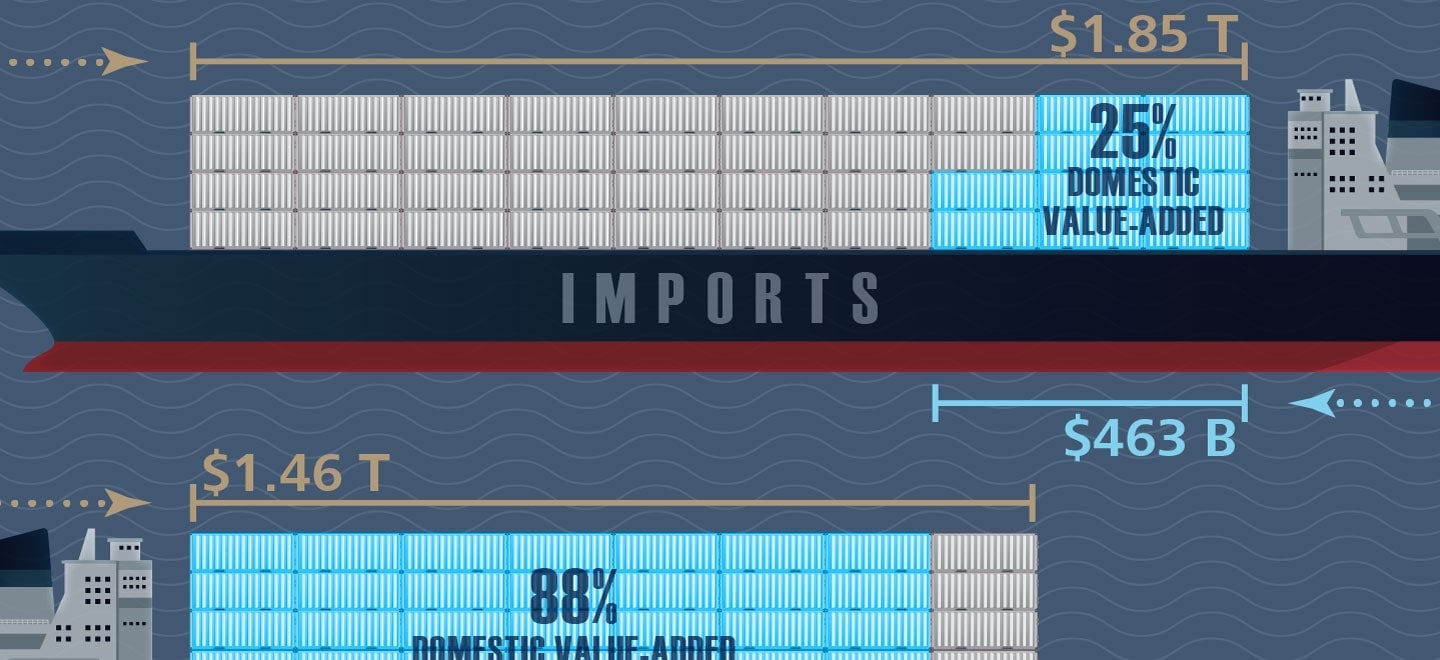

In 2009, the most recent year for which these data are available, 11.3 percent of the value of US exports was attributable to imported content (value added by other countries), while the remaining 88.7 percent reflected value added in the United States. Although this 88.7 percent is a decline from the 91.6 percent of domestic value added observed in 1995, it is still higher than the comparable figure for any other OECD country. On the import side, a quarter of the value of US imports actually represented re-importation of value that had originated in the United States (figure 1).

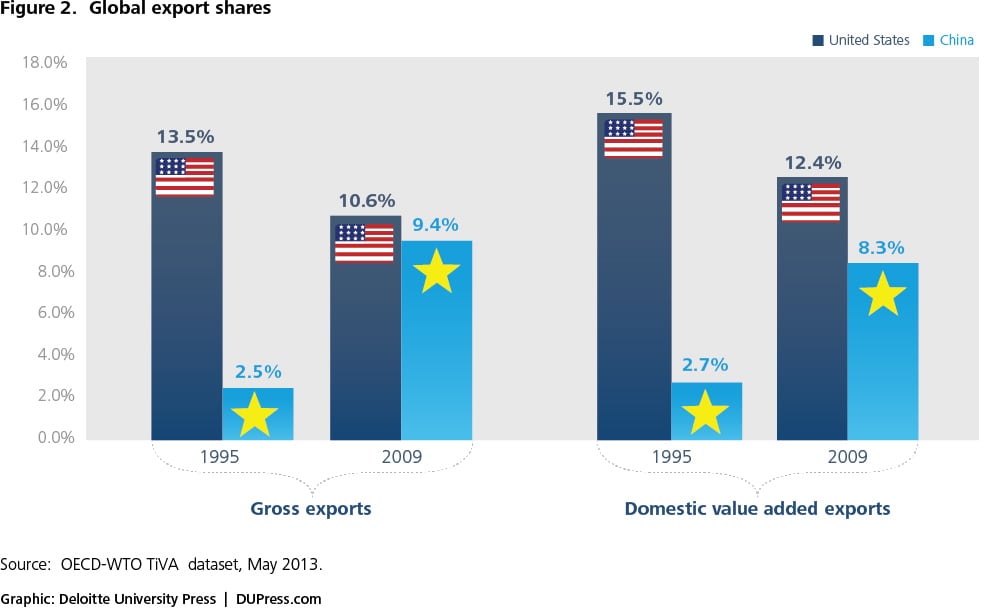

The United States’ high percentage of domestic value added in exports has implications for global rankings in export shares and for the way bilateral trade relationships are viewed. Figure 2 shows the change between 1995 and 2009 in the share of world exports accounted for by the United States and China. On a gross-flow basis, the United States’ share of world exports declined from 13.5 percent in 1995 to 10.6 percent in 2009. China, in contrast, increased its share of world exports from 2.5 percent to 9.4 percent during the same period. However, since the domestic value added of China’s exports declined from 88.1 percent in 1995 to 67.4 percent in 2009, the figures calculated on a value-added basis tell a different story. Although the United States’ share of world exports did decline while that of China increased, China’s increased share on a value-added basis is still considerably less than that of the United States.

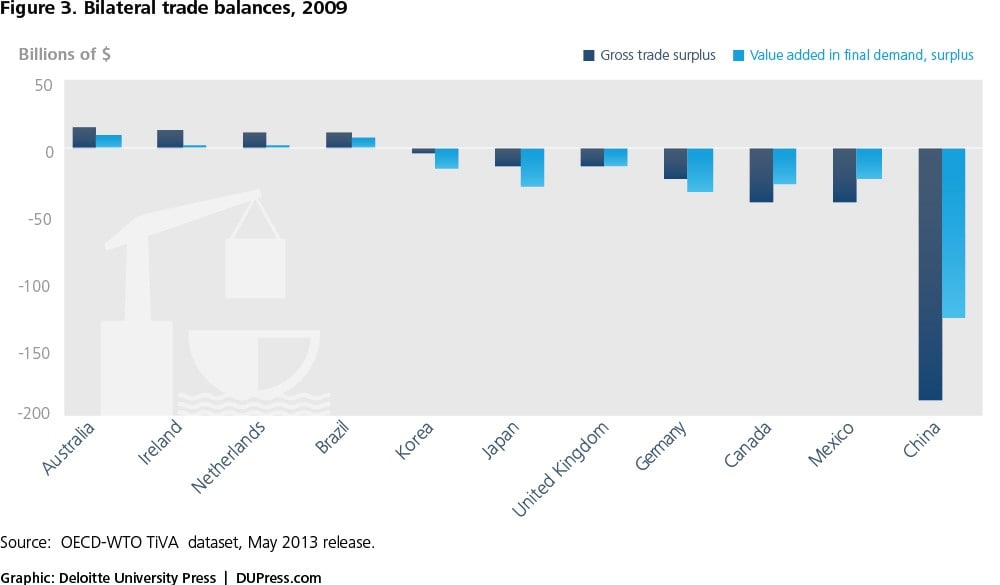

Because of differences in domestic value added embedded in exports and the intermediate imports included in exports, the United States’ bilateral trade balances are noticeably different on a value-added basis than on a gross-flow basis. For example, the United States’ trade deficit with China is one-third smaller in value-added terms than on gross-flow terms. Other differences include smaller deficits with Canada and Mexico and increased deficits with Germany, Japan, and Korea (figure 3).8

The rise of global value chains

A recent study by the OECD, the WTO, and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) prepared in advance of the 2013 G20 summit examined the expanding role of “global value chains,” or GVCs, in international trade. According to the study:

A value chain identifies the full range of activities that firms undertake to bring a product or a service from its conception to its end use by final consumers. Technological progress, cost, access to resources and markets, and trade policy reforms have facilitated the geographical fragmentation of production processes across the globe according to the comparative advantage of the locations. This international fragmentation of production is a powerful source of increased efficiency and firm competitiveness. Today, more than half of world-manufactured imports are intermediate goods (primary goods, parts and components, and semi-finished products), and more than 70 percent of world services imports are intermediate services.9

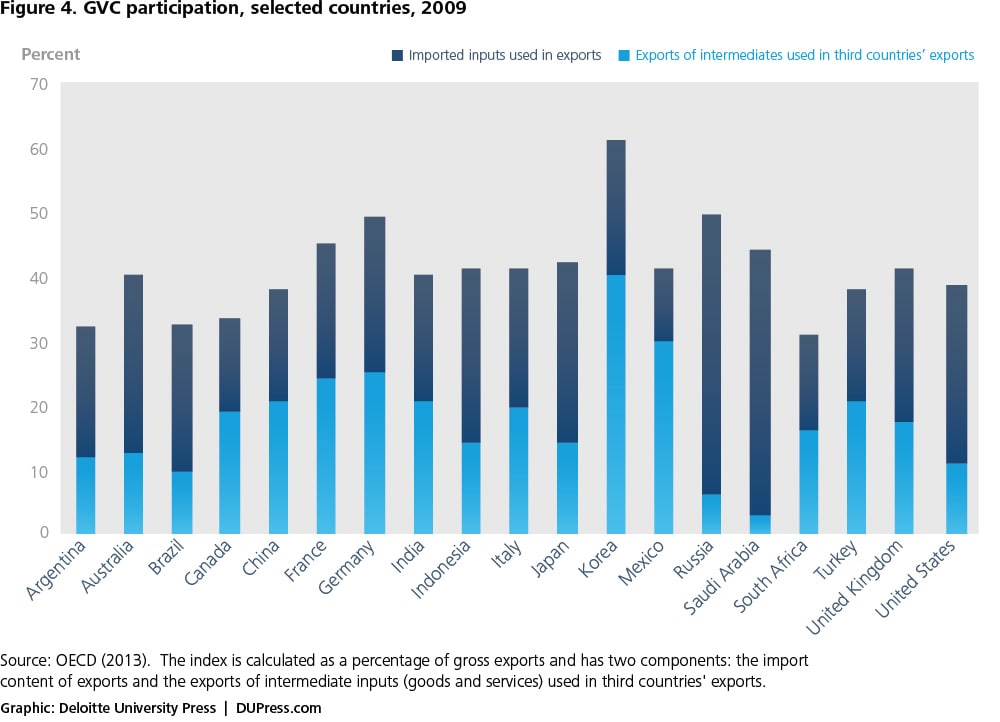

The report presented an index to quantify the degree to which a country is integrated into GVCs—the sum of exports of intermediates used in third countries’ exports and the imported inputs used in exports as a percentage of gross exports. Among the G20 nations, this index ranges from 30 and 60 percent of each country’s gross exports, with the United States falling in the mid-range at just under 40 percent (figure 4).

Focus on services

Traditional measures of trade show exports of goods playing a significantly larger role than the exports of services in the United States. However, these measures of gross flows are misleading. When the value added from trading partners is removed and the service contribution of goods is accounted for, services provide over 50 percent of the value added of exports.

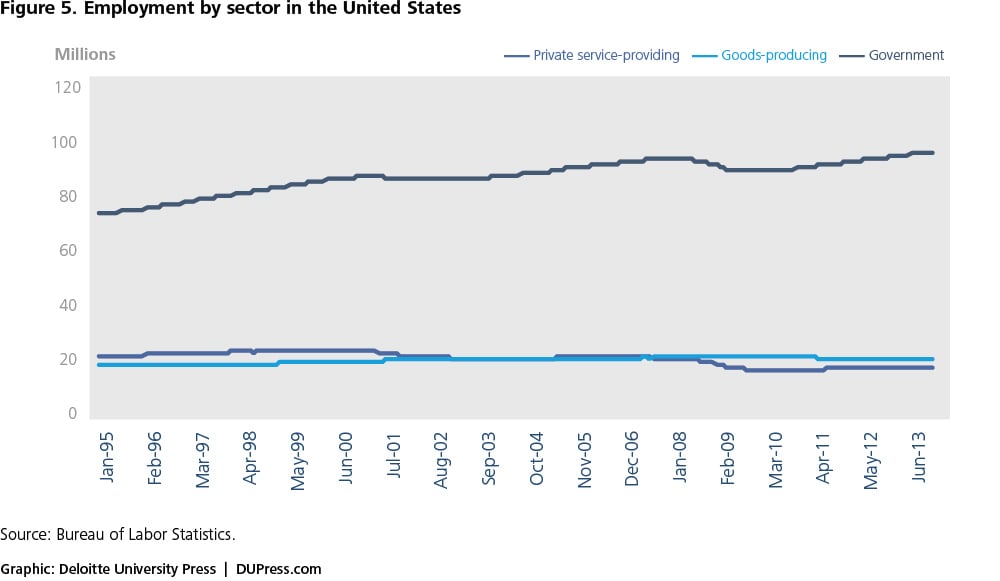

Employment in the United States has long been dominated by service sector employment, which currently accounts for 70 percent of total employment (figure 5). Even in terms of the output of the economy, the larger portion derives from the services sector. In 2012, private service sector industries contributed 69 percent of GDP, while the goods-producing sector contributed 18 percent.

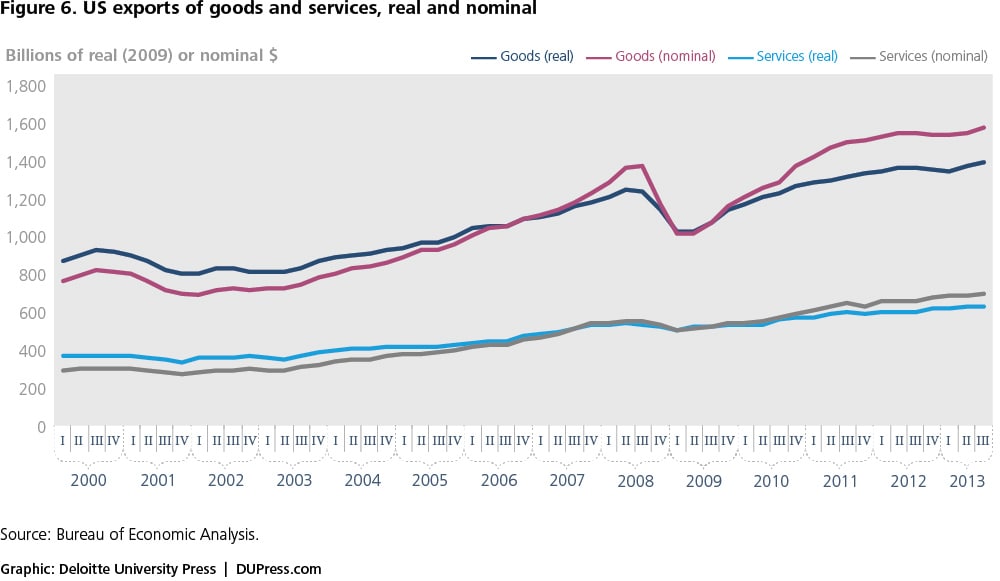

As shown in figure 6, when we look at the trade numbers, the relative importance of the two sectors initially seems to reverse, in both real and nominal terms.

Conventional wisdom suggests that the reason goods play a more significant role in trade than services is that they are more “tradable.” While it is true that for many services, the provider needs to be in close proximity to the customer (e.g., haircuts and restaurants), many services are also consumed in producing goods—including goods for export. These include services such as business and financial services, transportation, and warehousing.

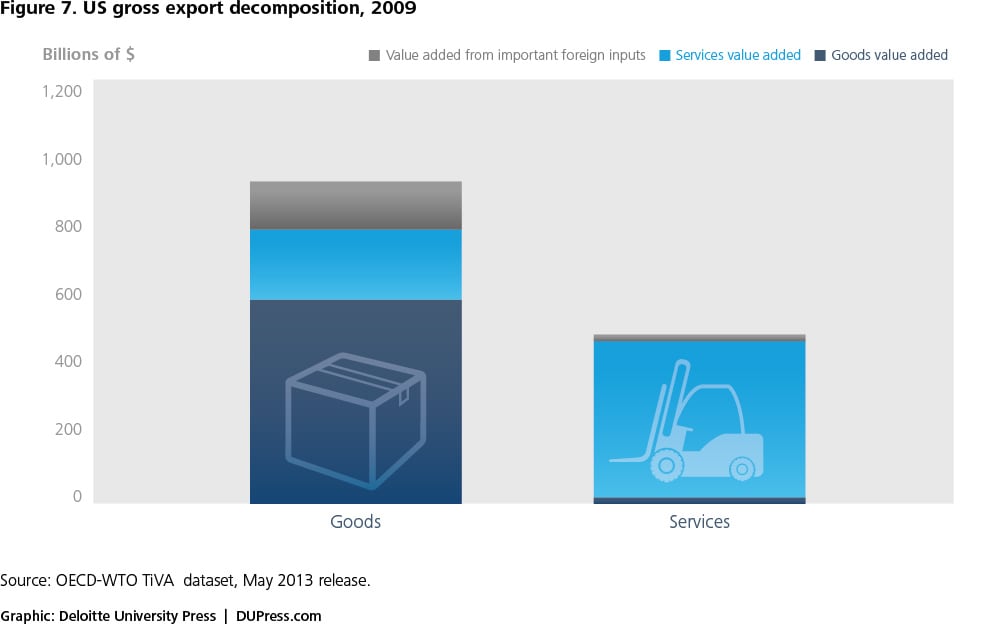

The following chart by Logan Lewis of the Federal Reserve Board illustrates the role that services play in creating value added in goods and services (figure 7).10 When the service value-added of goods and services production are combined, services contribute 53 percent of the value added of exports, while goods’ contribution is 47 percent.

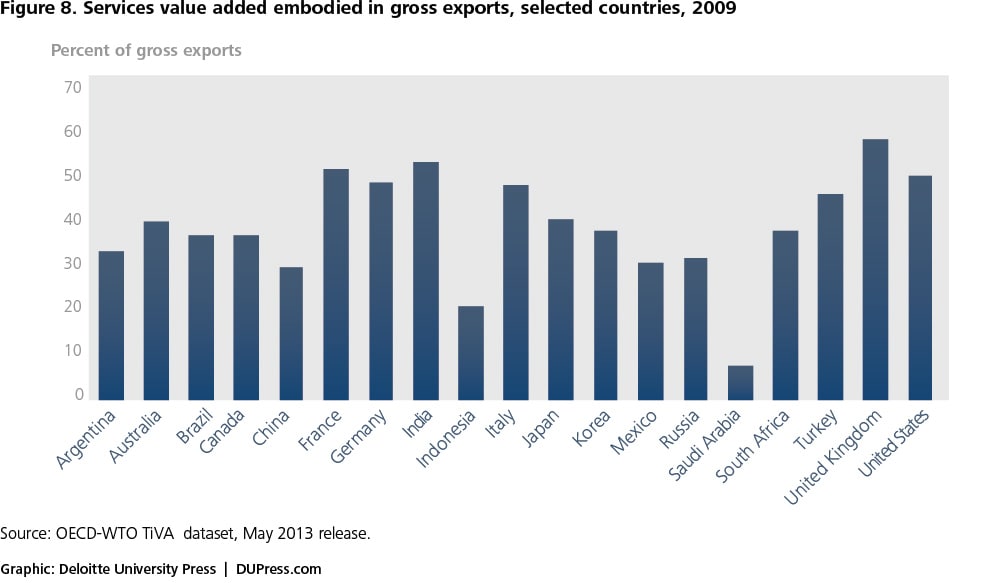

Although the combined service content of US gross exports is near the G20 average, the United States’ share of domestic services value added is surpassed only by the United Kingdom and Greece (not shown) (figure 8).

The possibilities of the TPP and the T-TIP

The data compiled by the OECD-WTO TiVA initiative provide important insight into why the TPP and T-TIP negotiations, as well as other multilateral negotiations such as the Trade in Services Agreement being discussed in Geneva, hold the possibility for real job creation and growth opportunities for the United States.

The relative strength of the US export sector should not be underestimated. US exports have a very strong “made in America” component—higher than the corresponding value-added calculation of all of our OECD partners. With growing supplies of domestic energy, the United States is well placed to reduce energy imports and increase its share of value added in exports even more as foreign oil content declines. Low cost and highly reliable energy supplies make the United States an even more attractive destination for foreign direct investment. Trade deals that increase our access to foreign markets and encourage direct foreign investment are a plus for the United States.

Increasing the efficiency of trade by decreasing regulatory costs through standardization and enhancing rules for protecting cross-border data flows build on the benefits already being delivered by GVCs. Efficiencies that can lower the cost of the imports that we use in our exports, and that can reduce the cost of US exports that are included in other countries’ production, enhance the competitiveness of US exports.

Even on a gross-flow basis, the United States has a surplus in services trade. The importance of services to our trade situation is even more striking, however, when the service component of our goods exports are highlighted. Both the agreements currently under negotiation specifically target trade in services as an area where market access can be increased and barriers, such as those covering the movement of people and credentialing, can be reduced or eliminated.

While, as always, the devil is in the details—and these negotiations are covering a multitude of highly contentious details—the real potential for these trade agreements to increase jobs and growth in the United States means that the hard work of negotiation could have a real payoff.