Breaking up is hard to do has been saved

Breaking up is hard to do How behavioral factors affect consumer decisions to stay in business relationships

27 June 2015

While emotional biases may help keep consumers “locked in” to unsatisfying business relationships, there is a price to be paid in terms of consumers’ attitudes toward a company’s offerings and the potential impact on future customers.

The hard part

This break has been years in the making. It happens all the time: The newness and the connection that placed the world at your fingertips have waned. Part of you knows that The Thrill Is Gone, and that part of you just wants to cut the cord and be done with it, even though the other part of you remembers how the relationship helped you through job changes and was always there while you mourned family members and pets. But lately, it seems like the relationship has been sprinkled with disconnects—lapses of dependability, inconsistent behavior, and missed dates. These myriad, subtle signals incessantly suggested that this relationship was never going to be enough. The two of you simply grew in different directions. Your outlooks and priorities don’t intertwine like they used to. You try not to take it personally, but you just can’t help feeling a little taken advantage of—like you aren’t as important as you once were.

At the same time, you’re noticing alternatives. Were they always there? Why is it that you are just noticing them now? Finally mustering the courage, you pick up your phone and send a text message—calling would be so awkward—saying you need to cancel your upcoming plans. Breaking up is hard to do. Now that it’s done, it’s time to move on to a new service provider.

Marketers focus an incredible amount of time and energy on developing lasting relationships with consumers. They allocate significant resources to this end and employ a number of tactics to kindle consumer “loyalty.” Concurre ntly, consumers often find themselves staying in a business relationship for reasons other than the value derived from the product or service they’re purchasing. While some of these reasons are tied to the lock-in strategies firms employ, others are not. Instead, they are rooted in the consumer’s personality and feelings of attachment or obligation.

ntly, consumers often find themselves staying in a business relationship for reasons other than the value derived from the product or service they’re purchasing. While some of these reasons are tied to the lock-in strategies firms employ, others are not. Instead, they are rooted in the consumer’s personality and feelings of attachment or obligation.

Behavioral economics—a research field that combines psychological and economic theories—helps to explain these consumer motivations to stick around. A recurring theme in this research is that cognitive biases often prevent people from acting in their own best interest.1 In other words, when weighing the pros and cons of existing service relationships, emotional biases often cloud our ability to make rational choices.

Within organizations, we often play the role of consumer—especially in procurement departments that manage indirect spend.2 While the total value varies among businesses and industries, indirect spend, on average, amounts to 50 percent of a company’s purchases.3 As organizational purchasers, we act as consumers of IT services (hardware, Internet, and telecommunications), office products, employee benefit plans, and many other products and services. Over time, these interactions may come to resemble close interpersonal relationships with the service provider representatives for each of these indirect spend categories. The decision to “stay or go” impacts the performance of both the individual and the organization that he or she represents. These stakes make it even more important to confront biases that might prevent us from maintaining positive service relationship commitments.

An exploration of external and self-imposed switching barriers

This article synthesizes recent research on the various reasons people stay committed to existing service relationships—even in cases where the relationship deteriorates for the consumer. We explore several facets of the business-to-consumer relationship dynamic. First, we identify master themes—or general aspects of the relationship—that individuals consider when evaluating business relationships. We then explore specific reasons consumers remain locked in to less-than-optimal service relationships, and highlight the behavioral theoretical underpinnings guiding these non-exit decisions. We close by suggesting guidelines a consumer might want to consider, either proactively before venturing into a relationship to minimize the potential for future lock-in, or retroactively while in an existing relationship to smooth the way for an “easy exit”—or at least to dial back the relationship.

A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management

Behavioral economics is the examination of how psychological, social, and emotional factors often conflict with and override economic incentives when individuals or groups make decisions. This article is part of a series that examines the influence and consequences of behavioral principles on the choices people make related to their work. Collectively, these articles, interviews, and reports illustrate how understanding biases and cognitive limitations is a first step to developing countermeasures that limit their impact on an organization. For more information visit http://dupress.com/collection/behavioral-insights/.

Why we stay

We stay in relationships—even bad ones—for many reasons. Recent research suggests that the decision to remain in a suboptimal service relationship is not a passive one. It’s an active, complex decision, and more often than not, it’s driven by more than one reason.4 A 2012 qualitative study interviewed individuals on a variety of service relationship types. The analysis focused on current business relationships the participants deemed were ones they “couldn’t easily leave or break up with.” Respondents were asked to talk about relationships they felt “at least somewhat negatively about” as well as those they felt “at least somewhat positively about.” (Refer to the “Study design” sidebar for more details).5

Study design

Three trained interviewers conducted 22 in-depth interviews with individuals (14 females, 8 males) from eight different states. Participants were asked to talk about current service provider relationships that they “couldn’t easily leave or break up with.” They were also asked to consider relationships they felt “at least somewhat positively about” and relationships they felt “at least somewhat negatively about.”

The most common positive service provider relationships mentioned were hairdressers, dentists, and home maintenance contractors. The most common negative service provider relationships mentioned were cell phone service providers, banks, and landlords.

Open-coding methods were used to identify concepts with common properties and dimensions. The data were clustered by category in order to identify recurring themes. Using axial coding, the data were then fit into an explanatory framework.

The synergistic effect of multiple reasons for staying

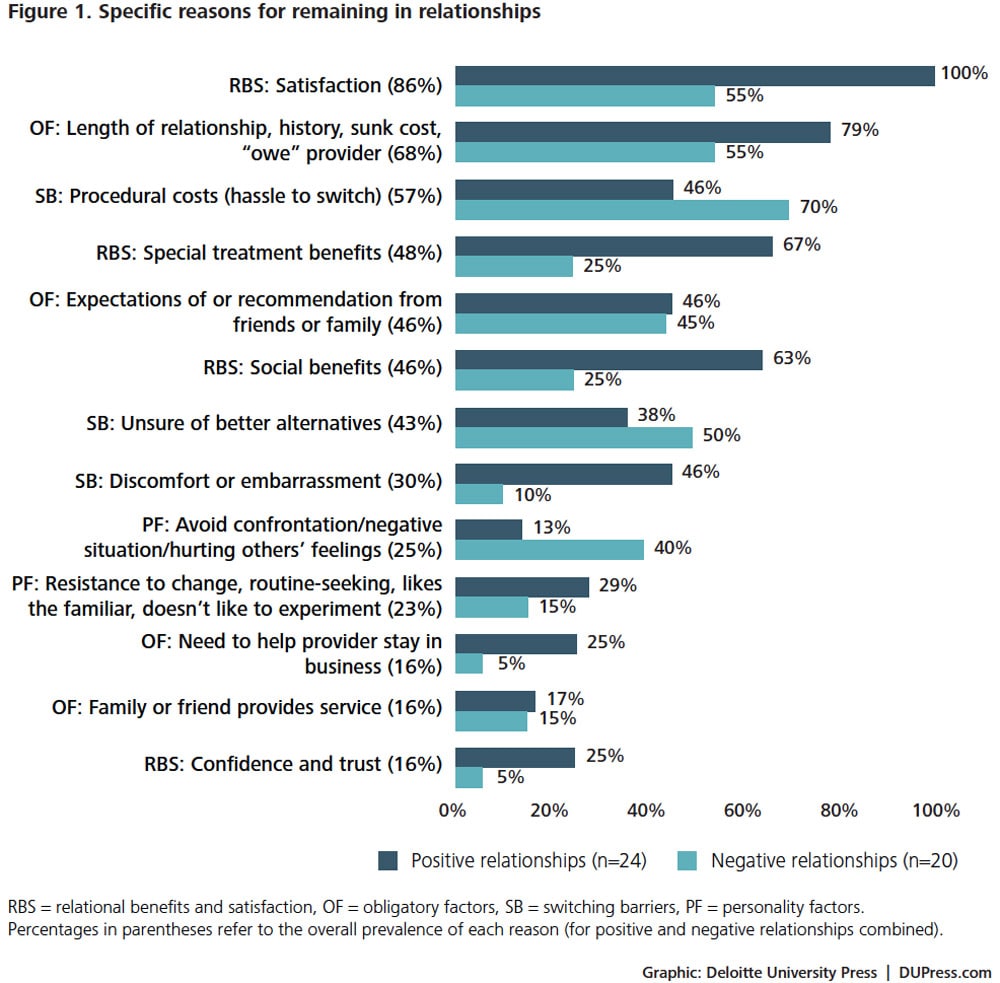

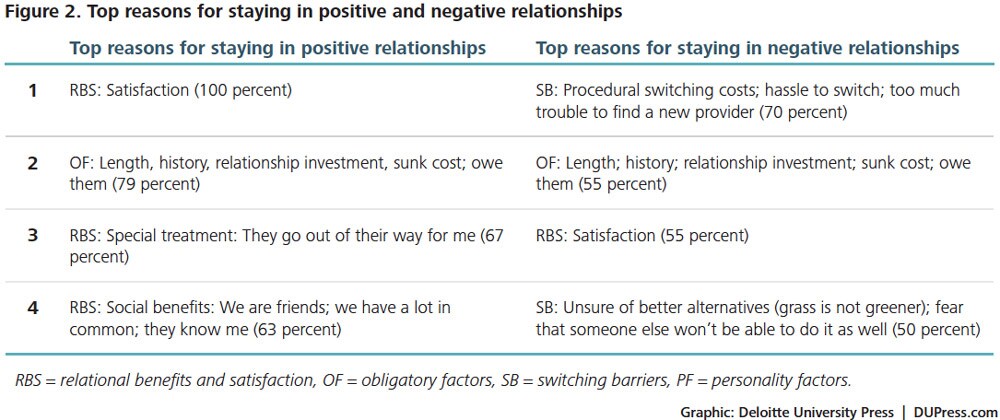

Thirteen specific reasons were identified as reasons people feel “locked in” to existing positive and negative business relationships. These reasons were then bucketed into four master categories: relational benefits and satisfaction (RBS), obligatory factors (OF), switching barriers (SB), and personality factors (PF) (refer to figure 1 for greater detail).

Two primary insights emerged from these interviews. First, people rarely feel locked into a service relationship due to a single reason; more often than not, their reasons span all four master categories. Specifically, less than 2 percent of the respondents cited just one reason for remaining with a provider. Conversely, over half (52 percent) of the respondents not only provided multiple reasons, but provided specific reasons across all four of the master categories—regardless of whether they deemed their current relationship to be positive or negative. Second, only one of the master categories mentioned—relational benefits and satisfaction (RBS)—can be considered truly positive. Interestingly, regardless of overall relationship positivity, satisfaction (86 percent) was the most common reason people stayed in service relationships, followed by relationship length, history and investment, and sunk cost (68 percent). Procedural costs associated with switching (for example, hassle, trouble finding a new provider) came in as the third most prevalent reason for staying, at 57 percent.

Even positive relationships are frequently peppered with obligation

As expected, the most common reason why consumers stay in positive relationships is satisfaction. However, even in positive relationships, consumers readily note that, despite their positivity toward the situation, they harbor feelings of being stuck or locked in—where exiting isn’t an option even if they wanted to. Highlighting this “lock-in” phenomenon, the second most frequently mentioned reason for staying in a positive relationship fell within the master category of “obligatory factors.” Specifically, respondents mentioned that relationship length, history, investment, sunk costs, and even feelings of owing the provider (79 percent) kept them tied to their service provider.

The third and fourth most common reasons for staying in a service relationship were, respectively, special treatment benefits (for example, “They go out of their way for me”) at 67 percent, and social benefits (for example, “We are friends,” “We have a lot in common,” “They know me”) at 63 percent. As with satisfaction, these reasons are positive, and fall in the broad category of relational benefits. It’s also worth noting that the presence of friendship within a service relationship seems to be a double-edged sword: Initially, it’s considered a carrot or at least a perk, but as the relationship matures, friendships frequently turn into obligations.

People have reasons of their own for staying in bad relationships

Motives for staying in negative relationships varied more widely than for positive relationships. The most common reason mentioned for staying in a negative service relationship was procedural switching costs—specifically, “Hassle to switch or too much trouble to find a new provider” (70 percent).

Taken together, we see that relationships are a mixed bag of emotions. Even with positive relationships come obligations and sunk costs. Figure 2 provides a summary of the top reasons for staying in relationships.

Behavioral factors influencing non-exit decisions

For every reason someone remains in a service relationship, behavioral research provides an explanation that supports this decision—even if it doesn’t produce an optimal outcome. Cognitive biases frequently keep people in a relationship that a more “rational” mindset may discard. Underlying each of the four master categories identified above (relational benefits and satisfaction, obligatory factors, switching barriers, and personality factors) are common behavioral influences that compel individuals to remain in service relationships. We explore each of these categories through the lens of behavioral research to determine the motives for why we stay in these service agreements. As we will see, oftentimes we stay for seemingly irrational reasons.

Stating the obvious: Seemingly logical reasons for staying put

Yes, satisfaction still matters. It is, not surprisingly, the concept that has received the most attention in the literature as to why we display repeated behavior and stay “loyal” to existing relationships.6 It’s worth noting that consumers indicate using a compensatory model—that is, they measure the various positive and negative aspects about their service provider (for instance, service quality, price, convenience) to inform their decisions to stay. Based on Milton Friedman’s economic rational choice theory, this would suggest that, as long as the perceived benefits outweigh the negatives in a relationship, consumers should be more likely to stay put. Conversely, if the negatives outweigh the benefits, consumers would be likely to exit a relationship.7

The zero-price-effect occurs when we systematically overvalue an item that is presented to us as “free.”

However, behavioral research suggests that we are not always equipped to properly weigh a relationship’s positive and negative attributes in an unbiased, rational manner. Furthermore, we tend to be incapable of making decisions in the absence of arguably irrelevant information, which invariably biases our decisions.

For example, receiving special treatment such as personalized or free services has been mentioned as a reason—or carrot—that keeps consumers loyal. This can be particularly effective when we believe others do not receive this same level of attention or extra service. Inherently, it feels good to be on the receiving end of free or extra services, and research helps us understand why. The zero-price-effect occurs when we systematically overvalue an item that is presented to us as “free.”8 “Free service” is indeed a great benefit when taken in isolation. However, when we are choosing between two alternatives and the worse option is free, our ability to weigh positives and negatives goes out the window. As a result, we tend to focus on the free “perks” rather than the holistic net value. Thus, free benefits may cloud our judgment.

Switching barriers: The glue that binds bad relationships

Switching barriers are a very powerful influence in consumers’ decisions not to leave a relationship. These can be thought of as the obstacles and costs customers must overcome in order to switch service providers. Procedural switching costs include the switching time, effort, and hassle a consumer anticipates. These are undoubtedly considered to be negative constraints. Study respondents often stated that they would rather stay than deal with the hassle of switching—citing the time necessary to gather records as well as find a new provider—even when the current relationship is less than optimal. The present bias explains this phenomenon: Humans naturally place more emphasis on payoffs occurring closer to the present than those taking place further in the future.9

Are we our own worst enemy? Self-imposed reasons for staying put

Obligatory factors: Behavioral decision making biases at their finest

The obligatory factor of staying in a relationship due to a long past history or a sense of owing the provider, while more prevalent in positive relationships (79 percent) than in negative relationships (55 percent), was the most common obligatory factor for both types of relationships. Behavioral research offers several explanations for our natural tendency to feel “obligated” to stay in a relationship.

By itself, relationship length is often enough to make us feel “locked in.” The behavioral concept of the sunk cost effect sheds light on this uniquely human behavior. This phenomenon occurs when consumers feel compelled to respond to previous investments by becoming increasingly willing to invest additional resources.10 In other words, when we have invested time, energy, and resources in a relationship, we feel that the past commitment justifies future investment—regardless of how promising future outcomes appear.

Reciprocity theory describes situations where we feel guilty about the idea of moving on to someone else after being on the receiving end of a “favor.”

Friends matter. The second most popular reason for consumers to stay in a service relationship was the perceived expectations of friends or family, mentioned equally often for positive (46 percent) and negative (45 percent) relationships. Study participants indicated that they believed that individuals close to them wanted them to stay in these relationships. Such social pressures are also described by behavioral research. Subjective norms suggest that individuals perceive the behaviors that others desire and expect from them as important. Stronger subjective norms interact with personality traits to influence behavior, but in general, the stronger the subjective norm, the more the individual feels compelled to act (or in this case, not act).11

A third dimension of obligation, the feeling of “owing,” compels many people to stay with a service provider as a way to repay the provider or to reciprocate. In this situation, consumers believe that a provider did them a “favor” such as coming in on a day off or otherwise going out of their way. Reciprocity theory describes situations where we feel guilty about the idea of moving on to someone else after having received a “favor.” This feeling of obligation to repay what another has already done is a very powerful influence factor and societal norm.12 Depending on the “favor,” reciprocity also works in conjunction with the zero-price-effect bias as a lock-in reason.

Personality factors: How individual differences influence our non-exit decisions

Personality can be thought of as distinctive stable characteristics or consistent behavior demonstrated by an individual. Personality traits include conflict avoidance, not wanting to hurt others’ feelings, and a preference for the status quo.

People who avoid confrontation prefer not to assert themselves in order to keep relationships smooth and preserve rapport.13 This personality trait had a greater impact on staying in negative relationships versus positive relationships. Confrontation avoiders value harmony, avoid expressing anger, and have a need to be seen as pleasant or nice.14 In line with this rationale, many consumers in the study described above expressed how much easier it was to stay in a less-than-perfect relationship rather than to confront the issue or person. Once again, we see the present bias at work: While avoiding conflict may seem like the better solution in the short term, conflict avoidance may also lead consumers to forego greater long-term satisfaction.

Those who value the consistency of existing routines may fall victim to the status quo bias.

People also vary in their comfort level regarding dealing with change. Those who value the consistency of existing routines may fall victim to the status quo bias.15 This resistance to change and preference for the status quo was mentioned twice as often as a reason for staying in positive relationships than for staying in negative relationships, suggesting that we do not necessarily have to be “upset” with a relationship to fall into this common behavioral trap. It may also indicate that many consumers fall into the trap of “satisficing”—settling for good enough as opposed to pursuing a better solution.

A person’s decision to satisfice may have less to do with their affinity for routines and more to do with the perceived risk associated with making a bad decision that compromises their situation. This preference for avoiding potential losses by sticking with the status quo instead of pursuing an uncertain potential gain is known as loss aversion.16

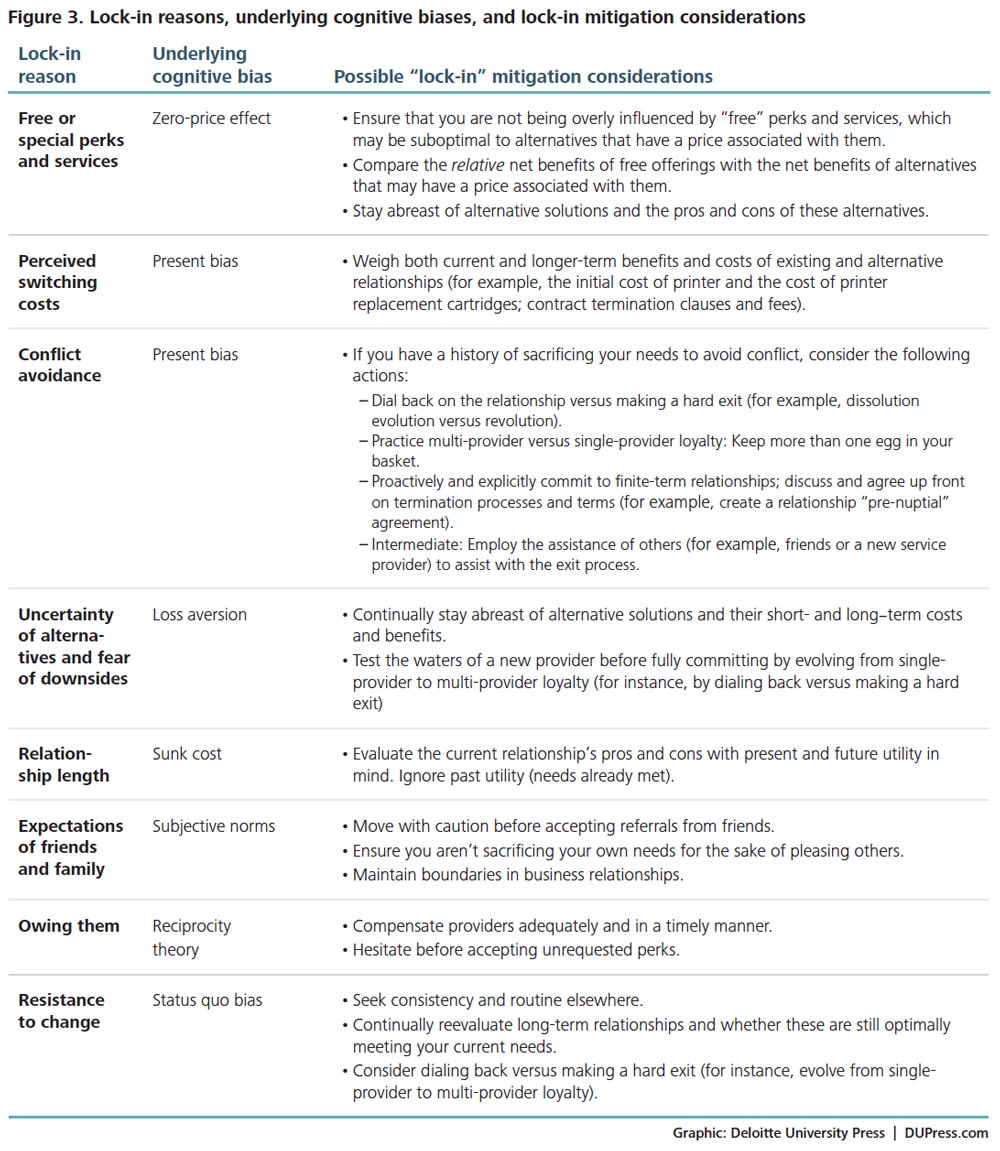

Consumer implications: Awareness of biases is necessary but not sufficient

Not all business relationships are bad, and we should not expect all business relationships to be perfect. Consumers understand that relationships are a mixed bag. They are generally quite adept at considering both the positive and negative aspects of existing relationships as they evaluate their quality. However, it is easy for us all to fall victim to a number of behavioral decision-making traps that cloud our ability to choose between taking off and staying put. Figure 3 summarizes various lock-in reasons, the underlying cognitive biases, and possible mitigation tactics.

Managerial implications: A cautionary tale of consumers present in body but not in spirit

“When someone consciously decides that an injustice is too small to deserve a response, that someone still exacts a price from the perpetrator. Typically, the consequence is a slight change in the level of respect for, positive attitude toward, or commitment to the perpetrator of the injustice. These incremental responses are the consequence of a small but nagging internal voice that demands attention.”17

We have spent most of our time focusing on the perspective of the buyer. However, many of us also act as a seller of some services, either to external clients or to colleagues within our own organization. Understanding the consumer motivations described in this report can also help us be better, more positive service providers within the relationships we keep. The following are reminders for the relationships we invest in:

1. Beware of relying on repeat behavior as a proxy for success

Managers should take heed that, while consumers may remain in existing business relationships, their continuance with the relationship does not imply they are necessarily content. Negative consequences that may occur when a dissatisfied consumer remains in a relationship include not only disaffection on the part of the consumer (such as negative feelings, detachment, and emotional disconnection), but also the risk that the consumer may vent frustrations to others, including potential customers.18

2. Compare the power of carrots to the prevalence of sticks

Carrots keep us in positive relationships; sticks keep us in negative relationships. While less prevalent overall as lock-in reasons, carrots represented many of the top reasons for study participants’ staying in positive relationships. As your organization allocates resources toward strategies that prevent consumers from leaving, consider the overall effect of sticks versus carrots on consumer attitude.

3. Remember the power of a personal service relationship

The study described in this report drew a distinction between “personal” relationships, where a consumer has repeated interactions with one service provider, and “pseudo” relationships, where, despite repeated contact with a provider, the consumer does not get to know any particular individual within the company. A disproportionate percentage (88 percent) of the positive relationships described by study participants involved a personal agent relationship, compared with only 50 percent of the negative relationships. Taken in isolation, this finding suggests that intimacy may lead to a more positive relationship—or conversely, less agent consistency or intimacy is more likely to lead to a negative relationship.

4. Don’t take long-term customers for granted

As noted above, the tendency to stick with the status quo, a tendency that gets stronger over time, legitimizes firms’ propensity to abuse existing relationships for the sake of new prospects. While providers that employ this tactic may keep existing customers, there is a price to be paid in terms of those customers’ attitudes toward the company’s offerings. Consider nurturing existing relationships and viewing long-term customers as advocates of your offerings—as opposed to cash cows.

Described below are some general recurring suggestions for how to avoid falling victim to relationship lock-in:

1. What got you here will not necessarily get you there: Beware of the lure of familiar, long-standing relationships

Relationship length is a powerful influence on our non-exit decisions. Just because something worked for you in the past, however, doesn’t mean it is the best solution moving forward. Sadly, the tendency to stick with the status quo—a tendency that gets stronger over time—legitimizes firms’ propensity to abuse existing relationships for the sake of new prospects. Many firms commonly allocate more resources toward new prospects and pull back on the resources allocated to existing relationships. Consumers can help themselves recognize when long-standing relationships turn sour by having a heightened awareness of this business tactic.

2. Know thyself: Proactively implement relationship guardrails to avoid repeating self-induced lock-in traps

The best indicator of the future often comes from looking to the past. If you have had a history of staying in relationships longer than you should have, consider proactively—ideally, before a relationship commences—putting in place the following guardrails:

- Hesitate before acting upon referrals from friends or colleagues.

- Avoid entering into business relationships with friends or family.

- Set boundaries to prevent business relationships from evolving into personal friendships.

- Decline special perks, favors, or services from providers; instead, compensate providers for these additional services if they are something you truly desire.

- Establish explicit relationship agreements and exit clauses (for example, a “pre-nuptial” agreement or termination clause).

These guardrails are especially worth considering when meeting potential service providers in after-business-hours networking events.

3. Consider alternatives to a hard exit: Relationship back-pedaling

More is not always better. While providers are continually trying to further engage consumers with their offerings, it is easy to forget that consumers make the ultimate decision about committing to an existing relationship. While it is helpful to draw analogies between business relationships and interpersonal relationships, let us not forget that the rules of engagement are not the same. With this in mind, consumers might consider moving from a monogamous (single-provider) to polygamous (multi-provider) relationship. This can alleviate loss aversion and conflict avoidance. Making the dissolution process more of an evolution than a revolution will help procurement consumers be aware of how a current business relationship compares with exiting alternatives.

4. Continual awareness of alternatives is imperative: Keep searching for information

A recurring undercurrent throughout is consumer uncertainty and fear regarding alternative solutions. A practitioner’s dream is to be the consumer's sole provider and single source of information. The onus is on consumers to keep themselves apprised of the alternatives that exist so that they accurately assess the pros and cons of their current business relationship, not only in isolation, but also relative to alternative solutions. For every service provider, develop an evaluation criteria to assess both individual and relative performance. Removing subjective sentiment can improve decision-making quality and reduce biases.

Relationships are complicated. This holds true for not only our personal relationships, but also the ones we form with providers on behalf of the organizations we serve. They are complicated because of all the moving parts that require consideration. Relational benefits, obligatory factors, potential switching barriers, and even our individual personality traits play into how we behave with respect to our service providers.

The good news is that when we understand and confront our biases in evaluating relationships, we can make life easier. Acknowledging our emotionally driven thought processes can empower us to employ mitigation techniques that let us follow a more productive line of thinking. Yes, breaking up is still hard to do, but hopefully, an enhanced awareness of the irrational ways we sometimes behave can help us feel a bit more confident that we are making the right choices.

Deloitte Consulting LLP’s Sourcing and Procurement practice develops executable strategies that are delivered through a combination of strong category experience, broad-based knowledge and skills, and a worldwide geographical reach to address the many facets of sourcing- and procurement-related engagements. The practice offers services in areas including direct and indirect materials sourcing, technology-enabled transformation, mergers and acquisition-related services, extended business relationship management, managed services, and talent development. Learn more about our sourcing and procurement offerings on www.deloitte.com.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.