API economy has been saved

API economy From systems to business services

30 January 2015

- David Sisk

Application programming interfaces can extend the reach of an organization’s core assets, allowing them to be shared, reused, or even resold as a new revenue stream.

Application programming interfaces (APIs) have been elevated from a development technique to a business model driver and boardroom consideration. An organization’s core assets can be reused, shared, and monetized through APIs that can extend the reach of existing services or provide new revenue streams. APIs should be managed like a product—one built on top of a potentially complex technical footprint that includes legacy and third-party systems and data.

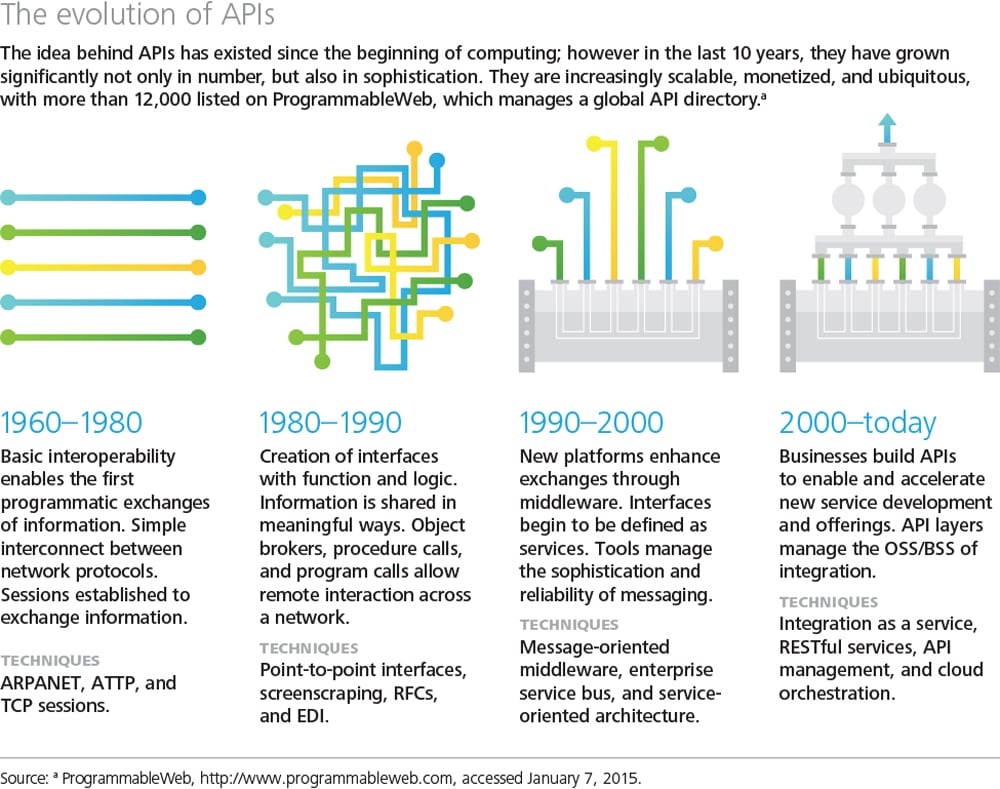

Applications and their underlying data are long-established cornerstones of many organizations. All too often, however, they have been the territory of internal R&D and IT departments. From the earliest days of computing, systems have had to talk to each other in order to share information across physical and logical boundaries and solve for the interdependencies inherent in many business scenarios. The trend toward integration has been steadily accelerating over the years. It is driven by increasingly sophisticated ecosystems and business processes that are supported by complex interactions across multiple endpoints in custom software, in-house packaged applications, and third-party services (cloud or otherwise).

Learn more

View all 2015 technology trends

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2015 report.

The growth of APIs stems from an elementary need: a better way to encapsulate and share information and enable transaction processing between elements in the solution stack. Unfortunately, APIs have often been treated as tactical assets until relatively recently. APIs, their offspring of EDI and SOA,1 and web services were defined within the context of a project and designed based on the know-how of small groups or even individual developers. As the business around them evolved, APIs and the rest of the legacy environment were left to accrue technical debt.2

Cut to today’s reality of digital disruption and diverse technology footprints. In many industries, creating a thriving platform offering across an ecosystem lies at the heart of a company’s business strategy. Meanwhile, the adoption of agile delivery models has put an emphasis on rapid experimentation and development. In addition, the application of DevOps3 practices has helped accelerate technology delivery and improve infrastructure quality and robustness. But interfaces often remain the biggest hurdles in a development lifecycle and the source of much ongoing maintenance complexity. Leading companies are answering both calls—making API management and productization important components of not just their technology roadmaps, but also their business strategies. Data and services are the currency that will fuel the new API economy. The question is: Is your organization ready to compete in this open, vibrant, and Darwinian free market?

Déjà vu or brave new world?

The API revolution is upon us. Public APIs have doubled in the past 18 months, and more than 10,000 have been published to date.4 The revolution is also pervasive: Outside of high tech, we have seen a spectrum of industries embrace APIs—from telecommunications and media to finance, travel and tourism, and real estate. And it’s not just in the commercial sector. States and nations are making budget, public works, crime, legal, and other agency data and services available through initiatives such as the US Food and Drug Administration’s openFDA API program.

What we’re seeing is disruption and, in many cases, the democratization of industry. Entrenched players in financial services are exploring open banking platforms that unbundle payment, credit, investment, loyalty, and loan services to compete with new entrants such as PayPal, Billtrust, Tilt, and Amazon that are riding API-driven services into the payment industry. Netflix receives more than 5 billion daily requests to its public APIs.5 The volume is a factor in both the rise in usage of the company’s services and its valuation.6 Many in the travel industry, including British Airways, Expedia, TripIt, and Yahoo Travel, have embraced APIs and are opening them up to outside developers.7 As Spencer Rascoff, CEO of Zillow, points out: “When data is readily available and free in a particular market, whether it is real estate or stocks, good things happen for consumers.”8

Platforms and standards that orchestrate connected and/or intelligent devices—from raw materials to shop-room machinery, from HVACs to transportation fleets—are the early battlegrounds in the Internet of Things (IoT).9 APIs are the backbone of the opportunity. Whoever manages—and monetizes—the underlying services of the IoT could be poised to reshape industries. Raine Bergstrom, general manager of Intel Services, whose purview includes IoT services and API management, believes businesses will either adopt IoT or likely get left behind. “APIs are one of the fundamental building blocks on which the Internet of Things will succeed,” he says. “We see our customers gaining efficiencies and cost savings with the Internet of Things by applying APIs.”

Future-looking scenarios involving smartphones, tablets, social outlets, wearables, embedded sensors, and connected devices will have inherent internal and external dependencies in underlying data and services. APIs can add features, reach, and context to new products and services, or become products and services themselves.

Amid the fervor, a reality remains: APIs are far from new developments. In fact, they have been around since the beginning of structured programming. So what’s different now, and why is there so much industry energy and investor excitement around APIs? The conversation has expanded from a technical need to a business priority. Jyoti Bansal, founder and CEO of AppDynamics, believes that APIs can help companies innovate faster and lead to new products and new customers. Bansal says, “APIs started as enablers for things companies wanted to do, but their thinking is now evolving to the next level. APIs themselves are becoming the product or the service companies deliver.” The innovation agenda within and across many sectors is rich with API opportunities. Think of them as indirect digital channels that provide access to IP, assets, goods, and services previously untapped by new business models. And new tools and disciplines for API management have evolved to help realize the potential.

Managing the transformation

Openness, agility, flexibility, and scalability are moving from good hygiene to life-and-death priorities. Tenets of modern APIs are becoming enterprise mandates: Write loosely coupled, stateless, cacheable, uniform interfaces and expect them to be reused, potentially by players outside of the organization.

Technology teams striving for speed and quality are finally investing in an API management backbone—that is, a platform to:

- Create, govern, and deploy APIs: versioning, discoverability, and clarity of scope and purpose

- Secure, monitor, and optimize usage: access control, security policy enforcement, routing, caching, throttling (rate limits and quotas), instrumentation, and analytics

- Market, support, and monetize assets: manage sales, pricing, metering, billing, and key or token provisioning

Many incumbent technology companies have recognized that API management has “crossed the chasm” and acquired the capabilities to remain competitive in the new world: Intel acquired Mashery and Aepona; CA Technologies acquired Layer 7; and SAP is partnering with Apigee, which has also received funding from Accenture.

But the value of tools and disciplines is limited to the extent that the APIs they help build and manage deliver business value. IT organizations should have their own priorities—improving interfaces or data encapsulations that are frequently used today or that could be reused tomorrow. Technology leaders should avoid “gold-plated plumbing” exercises isolated within IT to avoid flashbacks to well-intentioned but unsuccessful SOA initiatives from the last decade.

The shift to “product management” may pose the biggest hurdle. Tools to manage pricing, provisioning, metering, and billing are backbone elements—essential, but only as good as the strategy being deployed on the foundation. Developing disciplines for product marketing and product engineering are likely uncharted territories. Pricing, positioning, conversion, and monetization plans are important elements. Will offerings be à la carte or sold as a bundle? Charged per use, per subscription window, or on enterprise terms? Does a freemium model make sense? What is the roadmap for upgrades and new features, services, and offerings? These decisions and others may seem like overkill for early experimentation, but be prepared to mature capabilities as your thinking on the API economy evolves.

Mind the gap

Culture and institutional inertia may also be hurdles to the API economy. Pushing to share IP and assets could meet resistance unless a company has clearly articulated the business value of APIs. Treating them like products can help short-circuit the resistance. By targeting a particular audience with specific needs, companies can build a business case and set priorities for and limits to the exercise. Moreover, this “outside-in” perspective can help keep the focus on the customer’s or consumer’s point of view, rather than on internal complexities and organizational or technology silos.

Scope should be controlled for far more than the typical reasons. First, whether meant for internal or external consumption, APIs may have the unintended consequence of exposing poorly designed code that was not built for reuse or scale. Second, security holes may emerge that were previously lying dormant in legacy technical debt. Systems were built for the players on the field; no one expected the fans to rush the field and start playing as well—or for the folks watching at home to suddenly be involved. Finally, additional use cases should be well thought out. API designs and decisions about whether to refactor or to start again, which are potentially tough choices, should be made based on a firm understanding of the facts in play.

Mitigating potential legal liabilities is another reason to control scope. Open source and API usage are the subject of ongoing litigation in the United States and other countries. Legal and regulatory rulings concerning IP protection, copyright enforcement, and fair use will likely have a lasting impact on the API economy. Understanding what you have used to create APIs, what you are exposing, and how your data and services will be consumed are important factors.

One of the most important rationales for focus is to enable a company to follow the mantra of Daniel Jacobson, vice president of Edge Engineering at Netflix (API and Playback): “Act fast, react fast.”10 And enable those around you to do the same—both external partners and internal development teams. Investing in the mindset and foundational elements of APIs can give a company a competitive edge. However, there is no inherent value in the underlying platform or individual services if they’re not being used. Companies should commit to building a marketplace to trade and settle discrete, understandable, and valuable APIs and to accelerate their reaping the API economy’s dividends.

Lessons from the front lines

Fueling the second Web boom

APIs have played an integral role in some of the biggest cloud and Web success stories of the past two decades. For example, Salesforce.com, which launched in 2000, was a pioneer in the software-as-a-service space, using Web-based APIs to help customers tailor Salesforce services to their businesses, integrate into their core systems, and jump-start efforts to develop new solutions and offerings.11 Moreover, Salesforce has consistently used platforms and APIs to fuel innovation and broaden its portfolio of service offerings, which now includes, among others, iForce.com, Heroku, Chatter, Analytics, and Salesforce1.

In 2005, Google introduced the Google Maps API,12 a free service that made it possible for developers to embed Google Maps and create mashups with other data streams. In 2013, the company reported that more than a million active sites and applications were using the Maps API.13 Such success not only made APIs standard for other mapping services, but helped other Web-based companies understand how offering an API could translate into widespread adoption.

In 2007, Facebook introduced the Facebook Platform, which featured an API at its core that allowed developers to build third-party apps. Importantly, it also provided widespread access to social data.14 The APIs also extended Facebook’s reach by giving rise to thousands of third-party applications and strategic integrations with other companies.

By the late 2000s, streamlined API development processes made it possible for Web-based start-ups like Flickr, Foursquare, Instagram, and Twitter to introduce APIs within six months of their sites’ launches. Likewise, as development became increasingly standardized, public developers were able to rapidly create innovative ways to use these API-based services, spawning new services, acquisitions, and ideas. As some organizations matured, they revised their API policies to meet evolving business demands. Twitter, for example, shifted its focus from acquiring users to curating and monetizing user experiences. This shift ultimately led to the shuttering of some of its public APIs, as the company aimed to more directly control its content.

APIs on demand

In 2008, Netflix, a media streaming service with more than 50 million subscribers,15 introduced its first public API. At the time public, supported APIs were still relatively rare—developers were still repurposing RSS feeds and using more rudimentary methods for custom development. The Netflix release provided the company a prime opportunity to see what public developers would and could do with a new development tool. Netflix vice president of Edge Engineering, Daniel Jacobson, has described the API launch as a more formal way to “broker data between internal services and public developers.”16 The approach worked: External developers went on to use the API for many different purposes, creating applications and services that let subscribers organize, watch, and review Netflix offerings in new ways.

In the years since, Netflix has gone from offering streaming services on a small number of devices to supporting its growing subscriber base on more than 1,000 different devices.17 As the company evolved to meet market demands, the API became the mechanism by which it supported growing and varied developer requests. Though Netflix initially used the API exclusively for public requests, by mid-2014, the tool was processing five billion private, internal requests daily (via devices used to stream content) versus two million daily public requests.18 During this same period, revenues from the company’s streaming services eclipsed those of its DVD-by-mail channel, a shift driven in large part by Netflix’s presence across the wide spectrum of devices, from set-top boxes to gaming consoles to smartphones and tablets.19

Today, roughly 99.97 percent of Netflix API traffic is between services and devices. What was once seen as a tool for reaching new audiences and doing new things is now being used tactically to “enable the overall business strategy to be better.”20

In June 2014, the company announced that in order to satisfy a growing global member base and a growing number of devices, it planned to discontinue its public API program. Critics have pointed to this decision as another example of large technology companies derailing the trend toward increased access by rebuilding walls and declining external developer input.21 However, as early as 2012, Jacobson had stated, “The more I talk to people about APIs, the clearer it is that public APIs are waning in popularity and business opportunity and that the internal use case is the wave of the future.”22 Like any other market, the API economy will continue to evolve with leading companies taking dynamic, but deliberate approaches to managing, propagating, and monetizing their intellectual property.

Empowering the Beltway—and beyond

On March 23, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which reforms both the US health care and health insurance industries. To facilitate ACA implementation, the government created the Federal Data Services Hub, a platform that provides a secure way for IT systems from multiple federal and state agencies and issuers to exchange verification, reporting, and enrollment data.

The Hub acts as a single common entry point into federal, state, and third-party data sources without actually storing any data. As an example of how the Hub works, under the ACA, states are required to verify enrollee eligibility for insurance affordability programs. The Hub connects the state-based insurance exchanges to federal systems across almost a dozen different agencies to provide near-real-time verification services, including Social Security number validation, income and tax filing checks, and confirmation of immigration status, among others. State exchanges also use the Hub as a single entry point for submitting enrollment reports to multiple federal agencies.

The intent of the Hub’s technical architecture is to include scalable and secure Web services that external systems invoke via APIs. This system is designed to provide near-real-time exchange of information, which enables states to make benefits eligibility determinations in minutes instead of in days and weeks with the previous batch-based process and point-to-point connections. Moreover, with a growing repository of data and transactional services, the Hub can accelerate the development of new products, solutions, and offerings. And with common APIs, states are able to share and reuse assets, reducing implementation overhead and solution cost. The FDSH can also help agencies pay down technical debt by standardizing and simplifying integration, which has historically been one of the most complex factors in both project execution and ongoing maintenance.

Our take

Ross Mason, founder and vice president, product strategy

Uri Sarid, chief technology officer

MuleSoft

Over many years, companies have built up masses of valuable data about their customers, products, supply chains, operations, and more, but they’re not always good at making it available in useful ways. That’s a missed opportunity at best, and a fatal error at worst. Within today’s digital ecosystems, business is driven by getting information to the right people at the right time. Staying competitive is not so much about how many applications you own or how many developers you employ. It’s about how effectively you trade on the insights and services across your balance sheet.

Until recently, and for some CIOs still today, integration was seen as a necessary headache. But by using APIs to drive innovation from the inside out, CIOs are turning integration into a competitive advantage. It all comes down to leverage: taking the things you already do well and bringing them to the broadest possible audience. Think: Which of your assets could be reused, repurposed, or revalued—inside your organization or outside? As traditional business models decline, APIs can be a vehicle to spur growth, and even create new paths to revenue.

Viewing APIs in this way requires a shift in thinking. The new integration mindset focuses less on just connecting applications than on exposing information within and beyond your organizational boundaries. It’s concerned less with how IT runs, and more with how the business runs.

The commercial potential of the API economy really emerges when the CEO champions it and the board gets involved. Customer experience, global expansion, omnichannel engagement, and regulatory compliance are heart-of-the-business issues, and businesses can do all of them more effectively by exposing, orchestrating, and monetizing services through APIs.

In the past, technical interfaces dominated discussions about integration and service-oriented architecture (SOA). But services, treated as products, are what really open up a business’s cross-disciplinary, cross-enterprise, cross-functional capabilities. Obviously, the CIO has a critical role to play in all this, potentially as the evangelist for the new thinking, and certainly as the caretaker of the architecture, platform, and governance that should surround APIs.

The first step for CIOs to take toward designing that next-generation connected ecosystem is to prepare their talent to think about it in the appropriate way. Set up a developer program and educate staff about APIs. Switch the mindset so that IT thinks not just about building and testing and runtimes, but about delivering the data—the assets of value. Consider a new role: the cross-functional project manager who can weave together various systems into a compelling new business offering.

We typically see organizations take two approaches to implementing APIs. The first is to build a new product offering and imagine it from the ground up, with an API serving data, media, and assets. The second is to build an internal discipline for creating APIs strategically rather than on a project-by-project basis. Put a team together to build the initial APIs, create definitions for what APIs mean to your organization, and define common traits so you’re not reinventing the wheel each time. This method typically requires some adjustment, since teams are used to building tactically. But ultimately, it forces an organization to look at what assets really matter and creates value by opening up data sets, giving IT an opportunity to help create new products and services. In this way, APIs become the essential catalyst for IT innovation in a digital economy.

Cyber implications

APIs expose data, services, and transactions—creating assets to be shared and reused. The upside is the ability to harness internal and external constituents’ creative energy to build new products and offerings. The downside is the expansion of critical channels that need to be protected—channels that may provide direct access to sensitive IP that may not otherwise be at risk. Cyber risk considerations should be at the heart of integration and API strategies. An API built with security in mind can be a more solid cornerstone of every application it enables; done poorly, it can multiply application risks.

Scope of control—who is allowed to access an API, what they are allowed to do with it, and how they are allowed to do it—is a leading concern. At the highest level, managing this concern translates into API-level authentication and access management—controlling who can see, manage, and call underlying services. More tactical concerns focus on the protocol, message structure, and underlying payload—protecting against seemingly valid requests from injected malicious code into underlying core systems. Routing, throttling, and load balancing have cyber considerations as well—denials of service (where a server is flooded with empty requests to cripple its capability to conduct normal operations) can be directed at APIs as easily as they can target websites.

Just like infrastructure and network traffic can be monitored to understand normal operations, API management tools can be used to baseline typical service calls. System event monitoring should be extended to the API layer, allowing unexpected interface calls to be flagged for investigation. Depending on the nature of the underlying business data and transactions, responses may need to be prepared in case the underlying APIs are compromised—for example, moving a retailer’s online order processing to local backup systems.

Another implication of the API economy is that undiscovered vulnerabilities might be exposed through the services layer. Some organizations have tiered security protocols that require different levels of certification depending on the system’s usage patterns. An application developed for internal, offline, back-office operations may not have passed the same rigorous inspections that public-facing e-commerce solutions are put through. If those back-office systems are exposed via APIs to the front end, back doors and exploitable design patterns may be inadvertently exposed. Similarly, private customer, product, or market data could be unintentionally shared, potentially breaching country or industry regulations.

It raises significant questions: Can you protect what is being opened up? Can you trust what’s coming in? Can you control what is going out? Integration points can become a company’s crown jewels, especially as the API economy takes off and digital becomes central to more business models. Sharing assets will likely strain cyber responses built around the expectation of a bounded, constrained world. New controls and tools will likely be needed to protect unbounded potential use cases while providing end-to-end effectiveness—according to what may be formal commitments in contractual service-level agreements. The technical problems are complex but solvable—as long as cyber risk is a foundational consideration when API efforts are launched.

Where do you start?

At first glance, entering the API economy may seem like an abstract, daunting endeavor. But there are some concrete steps that companies can take based on the lessons learned by early adopters.

- What’s in a name? APIs should have the clarity of a well-positioned product—a clear intention, a clean definition of the value, and perhaps more important, a clearly defined audience. Is it a small set of known developers, a large set of unknown developers, or both? What is the trust zone? Public, semi-private, or private? How do these essential facts inform the scope and orientation of the service?

- Who’s on first? Top-down or bottom-up? Or more to the point: What will drive the API charge…business model innovation or technical services? The latter may be easier for an IT executive to champion, especially if the API is launched as part of a broader IT delivery transformation, technical debt reversal, or DevOps program. Placing the effort under an IT executive can also simplify the path forward and the expected outcomes by focusing on service calls, performance, standard adherence, shrinking development timelines, and lower maintenance costs.

- Planting the seed of how business services and APIs could unlock new business models may be trickier. But the faster the initiative is linked to growth and innovation, the better. In the early days of Amazon, Jeff Bezos reportedly issued a company-wide mandate requiring all technical staff, without exception, to embrace APIs. The mandate served as the foundation for the EC2 cloud computing platform, S3 storage cloud, warehouse management and fulfillment services, Mechanical Turk, and other initiatives.23

- Embrace the bare necessities. Organizations should consider what governance model they should establish based on the intended consumers (internal, partners, public at large) and whether the program is being driven by IT or the business. Tools such as API management platforms can provide a dashboard-like view into the inner workings of a solution landscape. The visibility provides a better handle on dependencies and performance of the core services across legacy systems and data.

- Avoid technology holy wars. There are many decision points, and they can become distracting. REST or SOAP for the service protocol? JSON or XML for the data formatting? Resource or experience-based design philosophy? Versioning via path segment, query string, or header (or none of the above)? Oauth2.0 or OpenID Connect security? What API management platform vendor should be used? These are all good questions that lack a single good answer. One size likely won’t fit all, and further consolidation and change in the vendor landscape is likely to continue. Companies should make appropriate decisions to guide shorter-term needs with a focus on pragmatism, not doctrinaire purity.

- Easy does it. Opportunities leveraging cross-industry cooperation may be tempting right out of the gate. However, businesses should decide if the payoff trumps the extra complexity. Companies should plan big, but start small. Ideally, they should use open, well-documented services to accelerate time to prototype. Expecting constant change and speedy execution is part of the shift to the API economy. Enterprises can use their first endeavors to anchor the new “business as usual.”

- Build it so they will come. If you are trying to launch external-facing APIs or platforms for the first time, you should ready yourself for a sustained campaign to drive awareness, subscriptions, and support. Beyond readying the core APIs and surrounding management services, companies shouldn’t forget about the required ancillary components: documentation, code samples, testing and certification tools, support models, monitoring, maintenance, and upkeep. Incentives and attempts to influence stakeholders should be tied to the target audiences and framed accordingly.

Bottom line

We’re on the cusp of the API economy—coming from the controlled collision of revamped IT delivery and organizational models, renewed investment around technical debt (to not just understand it, but actively remedy it), and disruptive technologies such as cognitive computing,24 multidimensional marketing,25 and the Internet of Things. Enterprises can make some concrete investments to be at the ready. But as important as an API management layer may be, the bigger opportunity is to help educate, provoke, and harvest how business services and their underlying APIs may reshape how work gets done and how organizations compete. This opportunity represents the micro and macro versions of the same vision: moving from systems through data to the new reality of the API economy.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.