Growth in outpatient care The role of quality and value incentives

15 August 2018

Medical procedures are moving into outpatient facilities, mainly due to technological advances such as minimally invasive surgical procedures. But value-based care incentives are also playing a role in this trend.

Executive summary

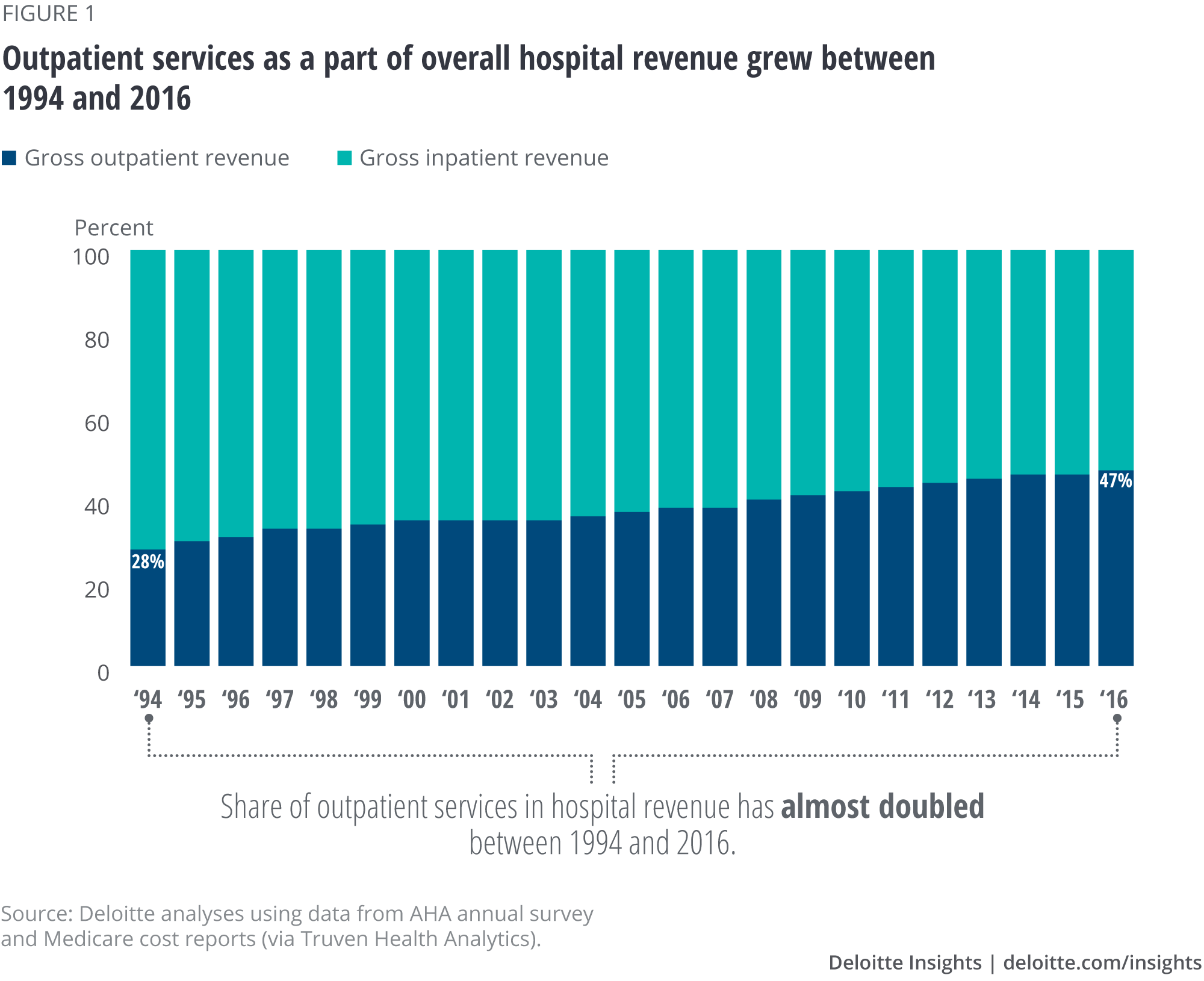

Clinical innovation, patient preferences, and financial incentives are tilting the balance in favor of outpatient settings for hospital services. Aggregate hospital revenue from outpatient services grew from 30 percent in 1995 to 47 percent in 2016.1 Some of this change is driven by patient preference and clinical and technological advances such as minimally invasive surgical procedures and new anesthesia techniques that reduce complications and allow patients to return home sooner.

Financial incentives have likely played a role as well. Health plans and government program payment policies support providing services in lower-cost care settings, including outpatient facilities.2 Health systems have also been acquiring or partnering with physicians and physician practices, further driving up the volume of services3 performed in outpatient settings.4

Learn More

Read more from the Health Care collection

Subscribe to receive Life Sciences & Health Care content

Moreover, these payers also are often using shared-savings, bundles, and other arrangements that tie payment amounts to cost and quality performance. One reason for the growth in outpatient care might be health systems’ strategies to perform well under these arrangements by reducing inpatient care by shifting patients to outpatient settings. To gain greater insight into the factors driving growth in outpatient services and decline in inpatient care, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions conducted descriptive and regression analyses using Medicare claims data between 2012 and 2015. Three key findings emerged:

- Hospitals with greater revenues from quality and value contracts provided more outpatient services than other hospitals. Hospitals that derive a large part of their revenue from quality and value contracts had 21 percent more Medicare outpatient visits and 13 percent higher outpatient revenue between 2012 and 2015 (even after controlling for hospital characteristics), compared with hospitals that did not report revenue from such contracts.

- The association between having these contracts and higher outpatient services was even more pronounced for certain therapeutic areas. The relationship was strongest for major diagnostic categories (MDCs) with higher rates of physician-hospital affiliation and technological change. Outpatient revenue was 18 percent higher for diseases of the circulatory system5 and 13 percent higher for diseases of the musculoskeletal system6 among hospitals with large incentives.

- All hospitals saw declines in inpatient revenues, but hospitals with greater revenues from quality and value contracts did not see steeper declines than other hospitals. The lack of a relationship between quality and value contracts and inpatient care may be because health systems are not yet at sufficient risk to actively manage population health to reduce inpatient care more aggressively.

Given the shift from inpatient to outpatient care, health systems will want to consider building effective strategies to grow capacity and infrastructure for outpatient services. These strategies generally have three components:

- Human and physical capital. Expanding outpatient services may call for additional physical and human capital (or their re-configuration) and workflow and operational improvements. Building physician relationships and networks through partnerships or affiliations (including with nontraditional health care entities such as retail health clinics) can help build capacity and attract patients.

- Virtual care/technology. Investing in virtual care/technology capabilities could expand outpatient services while also helping hospitals bend the cost curve and boost revenue.

- Case management/analytics. Health systems can work with physicians to use analytics and with patients to decide on which care setting is the most effective, safe, and efficient.

Hospital outpatient care is growing

Hospital inpatient stays have declined 6.6 percent over the past decade despite population growth and demographic shifts (such as an increasingly older, sicker Medicare population).7 In contrast, between 2005 and 2015, visits to outpatient facilities (see sidebar “Type of outpatient care settings”) increased by 14 percent—from 197 visits per 100 people in 2005 to 225 visits per 100 people in 2015.8 Hospitals’ gross outpatient revenue per visit increased at an even faster pace. Between 2010 and 2015, gross outpatient revenue per visit grew 45 percent, from $1,352 per visit in 2010 to $1,962 per visit in 2015.9 Health systems and hospitals have also increased their capital investments in outpatient facilities.10 As a result, as figure 1 illustrates, the aggregate share of outpatient services in total hospital revenue has grown over time—from 28 percent in 1994 to almost half (47 percent) in 2016.

Types of outpatient care settings

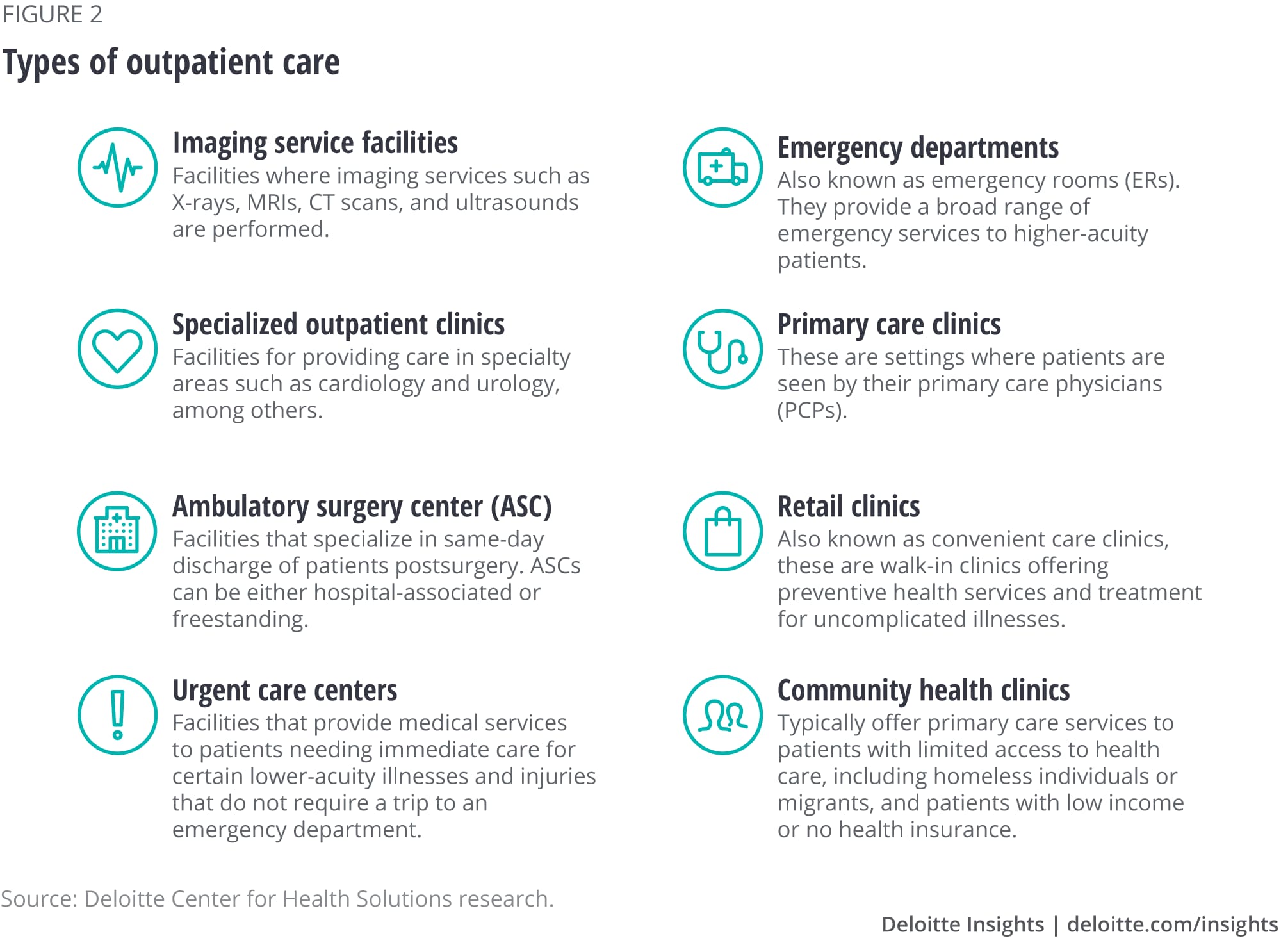

Health care services can be categorized into inpatient and outpatient depending on where the procedure is performed and the length of stay. Outpatient care refers to medical services and procedures, typically low-acuity ones that do not require an overnight hospital stay. Figure 2 below describes the primary types of hospital-based outpatient facilities.

Variation in outpatient services across states

Between 2012 and 2015, outpatient revenue grew faster than inpatient revenue in all but two states, according to our analyses. But, as figure 3 shows, the mix of hospital inpatient and outpatient services in 2015 varied significantly by state. In Nevada, for example, outpatient services accounted for 35 percent of total hospital revenue, while they made up 69 percent of Vermont hospitals’ revenue. This variation largely reflects a combination of regional differences in physician practice patterns and other market factors.

The increase in hospital outpatient services was pronounced in Medicare fee for service (FFS) between 2005 and 2015. During this period, outpatient services per beneficiary—which include outpatient visits and imaging services—grew 47 percent, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). Between 2006 and 2015, Medicare outpatient spending per beneficiary grew 8 percent annually from $885 in 2006 to $1,753 in 2015, according to MedPAC.11

What is driving the shift of hospital services to outpatient settings?

Innovation and improvements in clinical procedures likely played an important role in enabling this change.12 Many surgeries and medical and diagnostic procedures that once required an inpatient stay can now be performed safely in an outpatient setting. Patients have embraced these changes as outpatient services tend to cost less—and be more convenient—than inpatient services. Inpatient facilities tend to maintain more staff and have a wider range of capabilities, services, and equipment, including resource-intensive technologies that drive up costs. Furthermore, minimally invasive surgical procedures—such as laparoscopy and robotic surgery—and new anesthesia techniques that help prevent complications, have helped reduce recovery time for outpatient services and improved patient convenience.

Under Medicare payment policy, on-campus hospital-owned physician practices are paid more than independent physicians for the same services, which provides health systems with the incentive to buy physician practices.13 A MedPAC report found that physician-hospital consolidation increased between 2012 and 201414 and that in 2014, 39 percent of physicians who billed for Medicare in a large national database were affiliated with a health system or hospital. This consolidation could lead to more services being performed in hospital outpatient settings.

In addition to these trends, the increase in value-based payments might spur greater shifts from inpatient to outpatient care, to reduce total cost of care and improve patient experience. Health plans and Medicare and Medicaid programs are experimenting with payment models that reward better value (see sidebar “Main types of quality and value contracts”). These provide participating health systems with the incentive to shift services to lower-cost care settings, including outpatient ones.15 Indeed, some health care systems are building clinically integrated networks to help them perform more effectively in quality and value-payment models, partly by acquiring or partnering with physicians and physician practices.16

We wanted to explore whether hospitals that receive a higher share of revenue from quality and value contracts are seeing more services shift to outpatient settings. This question has not been studied well so far. We analyzed inpatient and outpatient claims data from a nationally representative 5 percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries from 2012 to 2015. We combined this data with information about hospital and market characteristics—such as hospital size, location (urban or rural), ownership type, teaching status, and case and payer mix. We also categorized hospitals by the degree to which they receive revenue from quality and value contracts (see the Appendix for further details).

Main types of quality and value contracts

Some health plans are tying payment to provider cost and quality performance through new payment arrangements such as:

- Shared savings. Under this arrangement, a provider organization is typically paid on a fee-for-service basis, but total annual spending is compared with a target. If spending is below that target, the organization receives a percentage of the savings (relative to the target) as a bonus.

- Shared risk. In addition to sharing savings (relative to a target), if a provider organization spends more than the target amount, it must repay some of the difference as a penalty.

- Bundled payments. Instead of paying separately for the hospital, physician, and other services, a health plan bundles payment for all services linked to a condition, reason for the hospital stay, and period of treatment. An organization can keep the money it saves through reduced spending on some component(s) of care included in the bundle.

- Partial/global capitation payments. An organization receives a per-person payment (usually per-month) intended to pay for all, or a specified subset, of individuals’ care, regardless of the services used.

Hospitals with higher quality and value incentives have more outpatient visits and revenue

We used hospital revenue data from quality and value contracts (“incentives”) to classify hospitals into three groups (see the Appendix for details):

- Hospitals with large (above the median) incentives;

- Hospitals with small (below the median) incentives; and

- Hospitals that report receiving no revenue from quality and value contracts.

Between 2012 and 2015, hospitals with any revenue from quality and value contracts accounted for about 10 percent of the approximately 3,500 hospitals in our database. We divided that group into two: those with large incentives had an average of 23 percent of their revenue from quality and value contracts, and those with small incentives received 3 percent of their revenue from such arrangements.

Hospitals with any incentives (large or small) generally differed from the rest. Hospitals with large incentives were more likely to be medium-sized (48 percent vs. 34 percent) and not for profit (73 percent vs. 49 percent), as well as to have a disproportionate share status (68 percent vs. 44 percent) and higher patient case mix (1.14 vs. 0.7), compared to hospitals with no incentives. To control for the possible influence of hospital characteristics on the association between outpatient services mix and quality and value incentives, we used a seemingly unrelated regressions estimation framework (see the Appendix).

Regression results reveal that, on average and controlling for their other characteristics, hospitals with any incentives had more outpatient visits and revenue than other hospitals. Moreover, we saw an even stronger relationship between outpatient services and quality and value contracts for hospitals with large incentives (figure 4). Compared with hospitals that did not report any revenue from quality and value contracts:

- Hospitals with large incentives had 21 percent more outpatient visits and 13 percent more outpatient revenue.

- Hospitals with small incentives had 16 percent more outpatient visits.

However, we did not see larger drops in inpatient visits and revenue for hospitals with any incentives, compared with other hospitals during the period we examined (figure 4).

Therapeutic areas with largest rates of physician-hospital affiliation and technological change saw the largest increases

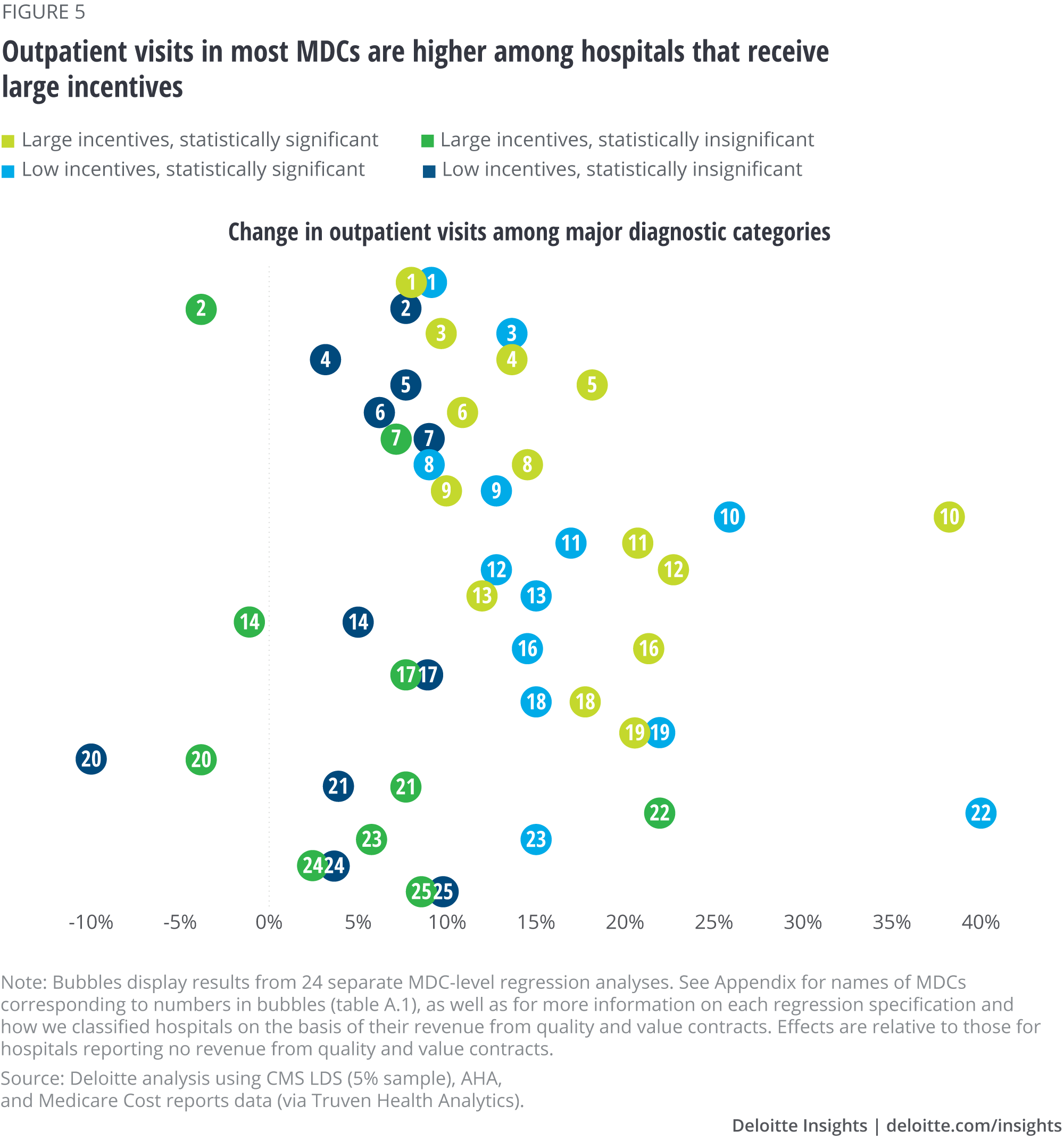

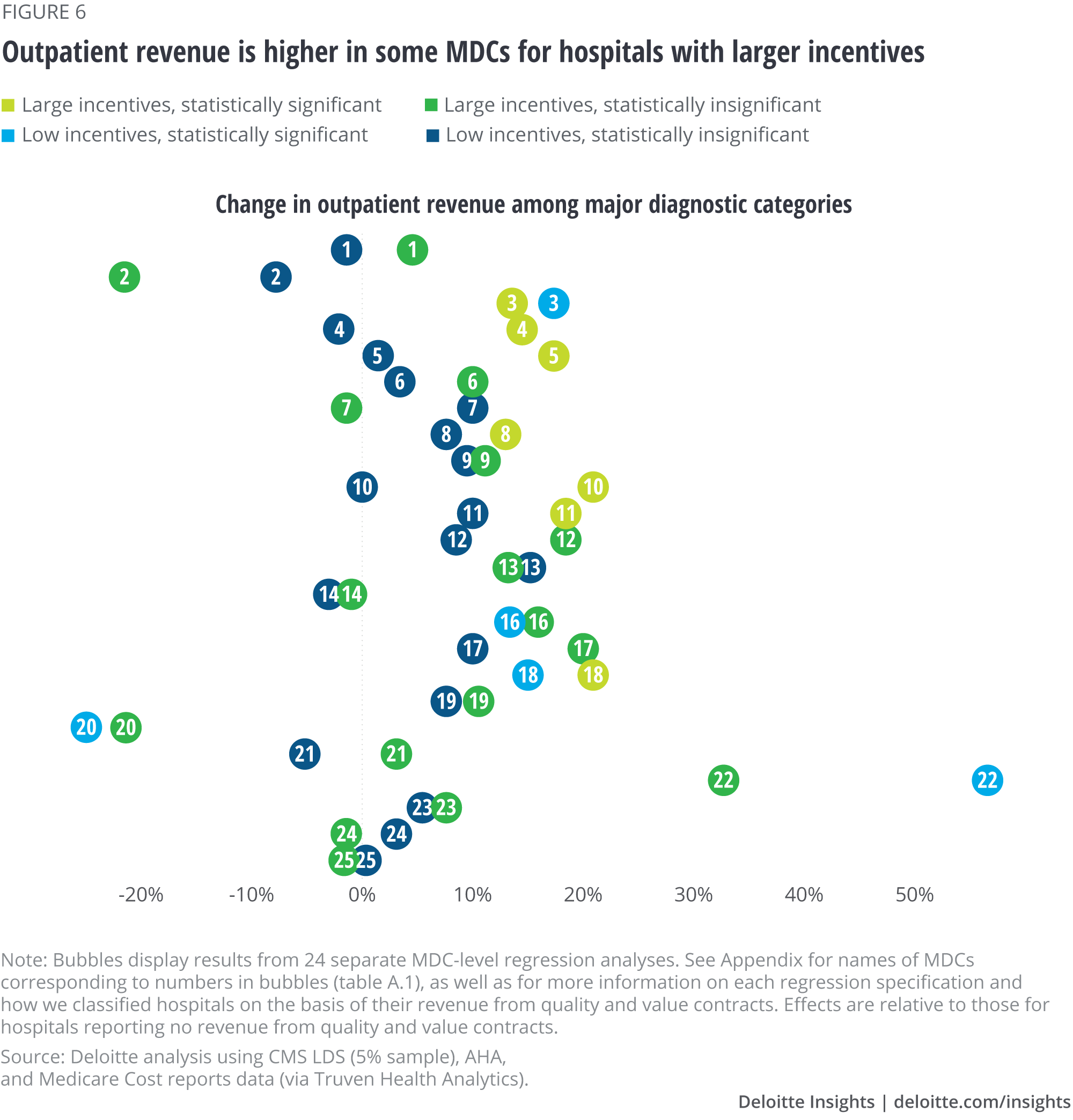

Was the relationship between growth in outpatient services and presence of incentives more pronounced in certain therapeutic areas? We found the relationship was strongest for major diagnostic categories (MDCs) with higher rates of physician-hospital affiliation and technological change. Outpatient revenue was 18 percent higher for diseases of the circulatory system17 and 13 percent higher for diseases of the musculoskeletal system18 among hospitals with large incentives.

We found that compared to hospitals reporting no revenue from quality and value contracts:

- Hospitals with large incentives had more outpatient visits than those with no incentives for 14 of the 24 MDCs that we studied (figure 5; for more details on MDCs, see the Appendix). We generally saw a stronger association for hospitals with large incentives. For instance, outpatient visits for endocrine and metabolic diseases and disorders were 37 percent higher among hospitals with large incentives (MDC 10 in figure 5) than among hospitals with no incentives. Outpatient visits for diseases and disorders of the kidneys, blood, male reproductive system, and mental health diseases were 20–22 percent higher among hospitals with the largest incentives (MDCs 11, 12, 16 and 19 in figure 5).

- Hospitals with large incentives had higher outpatient revenue than those with no incentives for 7 of the 24 MDCs that we studied: diseases and disorders of the ear, nose, and mouth (MDC 3 in figure 6); respiratory system (MDC 4); circulatory system (MDC 5); musculoskeletal system (MDC 8); endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic system (MDC 10); kidney and urinary tract (MDC 11); and infectious and parasitic diseases (MDC 18).

- We did not see statistically significant reductions in inpatient visits and revenue among hospitals with quality and value incentives for any of the MDCs that we studied. There are three possible reasons for this finding—one, it may be that there are too few hospitals with major exposure to contracts to find an effect. Two, it may be that hospitals are early into their population health strategies and starting with building outpatient capacity rather than decreasing inpatient care aggressively (especially given that they are still paid under fee-for-service for a significant share of their business). Finally, our data may not capture the nuances of the risk borne under these contracts.

What might explain the relationship between incentives and outpatient volume in the different therapeutic areas? We see a stronger relationship between incentives and outpatient visits and revenue for therapeutic areas that have seen high physician-hospital affiliation and technological change throughout the period of our study. Among physicians who bill Medicare, for instance, 53 percent of cardiologists and 35 percent of orthopedists reported hospital or health system affiliation in 2014.19 Outpatient revenue from diseases of the circulatory system20 was 18 percent higher among hospitals with large incentives (MDC 5 in figure 5). For diseases of the musculoskeletal system,21 outpatient revenue was 13 percent higher (MDC 8).

Examples of innovations in MDCs that are driving migration of treatment to outpatient settings

Diseases and disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Laser spine surgery is a minimally invasive procedure that no longer requires an inpatient stay. Endoscopy and live imaging are used to visualize the damaged disc, and the damaged tissue is removed using a precision laser. Since the surgical scar is small, little or no postsurgery care is typically needed.22

Diseases and disorders of the circulatory system. Certain cardiology interventions—such as catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and stent and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasties—are increasingly performed in outpatient settings.23 For instance, over 45 percent of all PCI procedures shifted from the inpatient to the outpatient setting between 2004 and 2014.24 The change was largely driven by safety improvements stemming from clinical and technological innovations such as the use of radial access, less contrast material, bleeding risk assessments, better anticoagulation options, and improved disposable products.

Diseases and disorders of the digestive system. A growing number of bariatric surgeries are performed on an outpatient basis. For instance, gastric balloons ingested by patients to achieve weight loss can now be removed endoscopically, without the need for anesthesia or incision.25

Diseases and disorders of the ear, nose, throat, and mouth. Improvements in safety, combined with technological advancements such as “dropless” surgery, mean that most cataract surgeries can now be performed in outpatient settings.26

Diseases and disorders of the respiratory system. More than 70 percent of patients who undergo thoracoscopic surgery can be discharged on the day of surgery itself due to the use of new techniques and technologies such as short endoscopes with small incisions and advanced robotic technological aids.27

Implications

Our original hypothesis was that we would find a more pronounced shift from inpatient to outpatient care among health systems with greater value and quality incentives. While we found higher use of outpatient care, we did not find lower use of inpatient care than for other hospitals. One reason may be the very small proportion of hospitals with any type of incentive contracts at all, the relatively recent experiences with these contracts, or the limited amount of risk these hospitals may be facing.

Nevertheless, it is interesting to find that hospitals with incentives have greater outpatient services. Many hospitals are trying to increase their outpatient services both as a defensive mechanism to react to new and more aggressive competitors and to diversify their revenues. Greater outpatient business may also position hospitals to do well under contracts that consider the whole spectrum of care in the future and that reward closer physician-health system collaboration.

Going forward, hospitals and health systems, especially those that get a large portion of their revenue from value contracts, will likely have to address the need to move treatment from inpatient to outpatient settings. Is there a road map for this transition?

Health systems may want to consider their investments in both human and physical capital. Expanding outpatient services may call for building partnerships with organizations that now have the capacity (for example, ambulatory surgery centers, outpatient clinics, and retail centers) and human capital (physicians and other clinical staff) to support care in these settings, as well as considerations around referral patterns, workflow, and operational improvements. Building physician relationships and networks through partnerships or affiliations can help increase capacity and attract patients. Capacity and capabilities can help health systems succeed in both fee-for-service payment systems and value-payment arrangements.

Virtual care/technology can be a part of the outpatient strategy, allowing health systems to add capacity and generate referrals as well as provide a lower-cost setting for treatment.

Finally, technology can help health systems manage operations and patient care more efficiently. For example, case management, supported by analytics, can help health systems work with patients to decide on which care setting is the most effective, safe, and efficient.

Appendix

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions performed regression analyses to study the association between quality and value incentives and hospital inpatient and outpatient visits and revenue. We used controls for factors that could influence this association, including hospital organizational characteristics (such as hospital size, urban/rural location, ownership type, service mix, teaching status, and being part of a system), case and payer mix, as well as local market conditions.

The seemingly unrelated regressions model

Our main regression specification was a system of four linear equations (one for each of the four hospital service metrics) of the following form:

Hospital services metrics = f (quality and value incentive indicators, hospital organizational characteristics, case and payer mix, local market characteristics, and year indicators)

The variables are as follows:

- Hospital services metrics. Outpatient and inpatient revenue and visits, in log form.

- Quality and value incentive indicators. Large incentives (hospitals with above the median share of revenue coming from quality and value contracts); smaller incentives (hospitals with below the median share of revenue coming from quality and value contracts).

- Payer and case mix variables. Medicare and Medicaid shares in payer mix, an indicator for disproportionate share status, case mix index, intensive care indicators, and nonacute share in total patient days.

- Hospital organizational characteristics. Indicator for the hospital being part of a system, ownership (indicators for government and not-for-profit hospital ownership), and size (indicators for small and medium hospitals).

- Local market conditions. Area wage mix index, critical access indicator, urban location indicator, state indicators.

- Indicators for each year between 2012 and 2015.

In these models, the unit of observation is the hospital-year cell. In the MDC analyses, the unit of observation is the hospital-MDC-year cell. Since we include state and year indicators, the association between quality and value incentives and hospital service mix is estimated from changes in incentives in a given hospital over time, as compared to other hospitals with similar characteristics in the same state. We use a seemingly unrelated regression estimation framework to account for the correlations between our hospital service metrics, and we correct the standard errors for clustering on hospital referral regions (HRRs). The adjusted R-squared in our estimations varied between 70 and 79 percent.

Major diagnostic categories (MDCs)

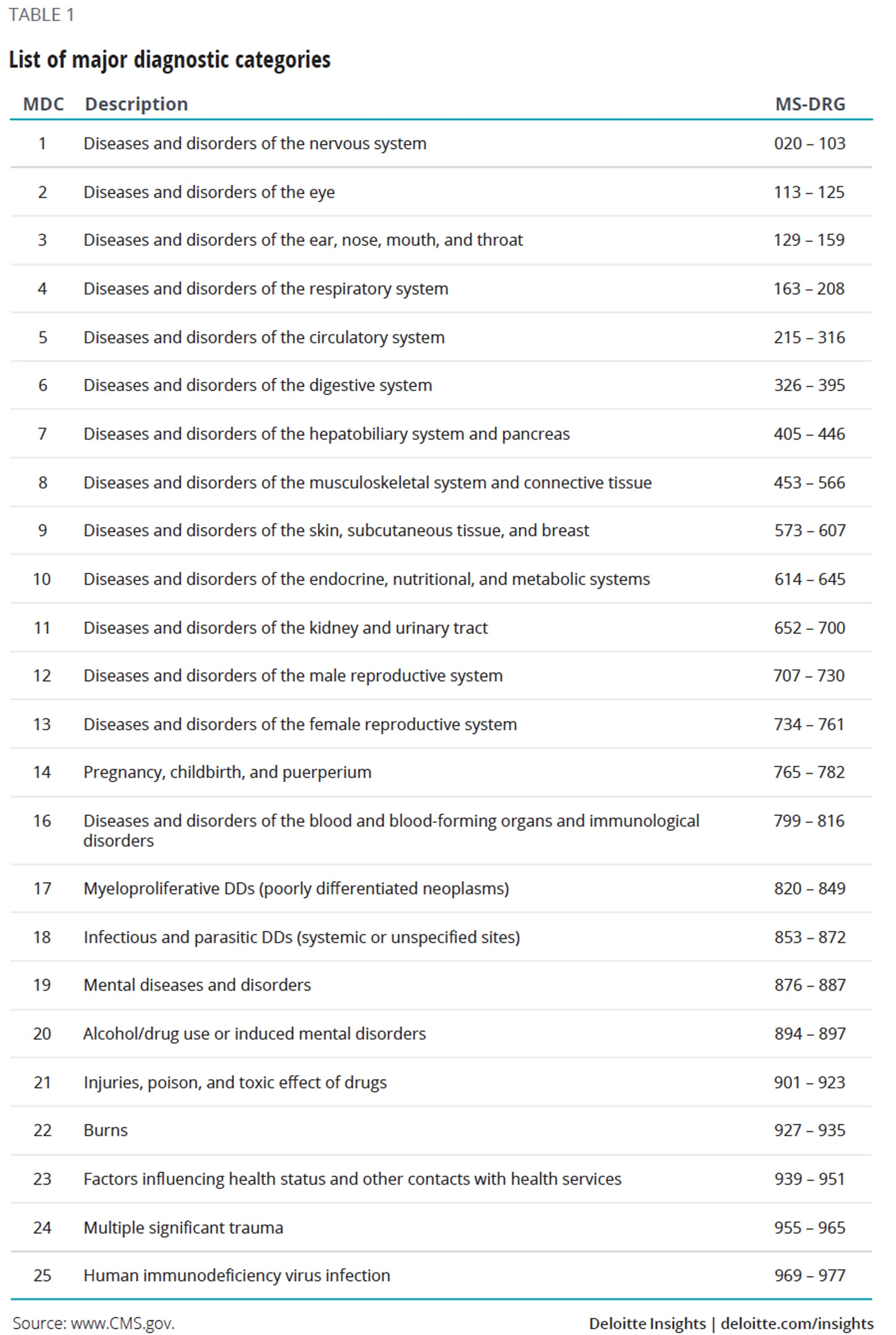

We mapped the ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes from the Medicare LDS claims data to their respective diagnosis-related groups (MS-DRGs), which were in turn mapped to their respective MDCs. MDCs were devised by physician panels to ensure DRGs are clinically coherent, since MDCs are mutually exclusive categorizations of all possible diagnosis codes. Each MDC corresponds to a single organ, system, or medical specialty. Public health departments28 use MDC coding in their inpatient discharge and emergency department modules.

In our data, information was not available for MDC 15 (newborns and neonates with conditions). The 24 other MDCs we analyzed are listed below in table 1.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.