Nudging for good Using behavioral science to improve government outcomes

6 minute read

24 June 2019

Shrupti Shah United States

Shrupti Shah United States John O'Leary United States

John O'Leary United States Jim Guszcza United States

Jim Guszcza United States Jane Howe United States

Jane Howe United States

Government is increasingly using nudge thinking—designing environments in ways to help humans make better decisions—to improve outcomes in areas ranging from tax compliance to retirement savings.

Ten years ago, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book Nudge introduced the powerful concept of choice architecture: the idea that subtle tweaks to choice environments can significantly impact our decisions. By designing choice environments in ways that work in harmony with human psychology, we can prompt better decisions—decisions that individuals would make if they had unbounded cognitive abilities and no self-control problems.

Behavioral science, or “nudge thinking,” is the use of choice architecture and other techniques to try to influence the choices people make. Academic research has provided powerful theories about human decision-making, and these theories have shown impact in real-world settings across the globe. It turns out that human beings are often busy, distracted, and socially motivated. As a result, our “decisions” are often the result of subconscious, nonrational influences. If the default option for our 401(k) is to invest, we are more likely to save for retirement. If we know our neighbors are recycling, we are more likely to recycle. And if the financial aid form is prepopulated with the family’s income data, the student is more likely to attend college.

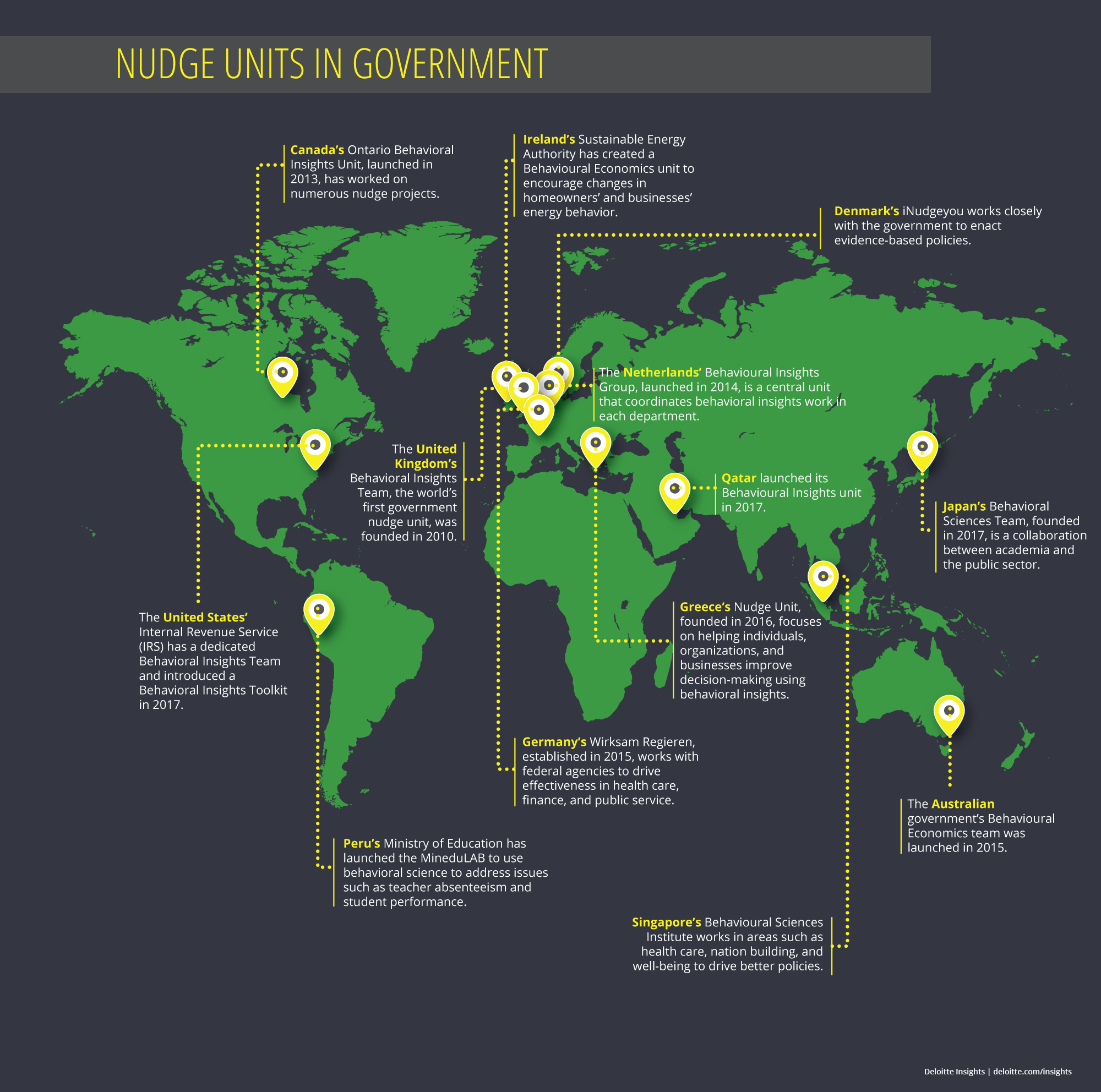

Though private companies are increasingly taking notice, government agencies have been in the vanguard of this movement, testing nudge theories in hundreds of real-life settings around the world.

In 2010, the United Kingdom’s Behavioural Insights Team became the first governmental “nudge unit” to study and harness behavioral patterns for more informed policymaking and improved government services.1 Since then, there has been a proliferation of formal and informal nudge groups within government agencies, as hundreds of countries, states, and cities have applied the concepts of nudge thinking to improve outcomes.2

Broad use cases across government. Recent years have seen nudges go from a novelty to a commonly used tool in the public sector thanks to the presence of hundreds of government nudge units and their impressive track record of beneficial results. Nudges have increased tax compliance in the United Kingdom3 and the United States,4 and reduced littering in Scotland.5 Nudges have encouraged citizens to save more for their retirement in Oregon,6 more businesses to comply with regulations in Ontario, Canada,7 and pedestrians to stop jaywalking in Bogota, Colombia.8

In public health, in order to reduce antibiotic over-prescribing, the Australian Department of Health’s Behavioural Economics and Research Team (BERT) identified general practitioners with high antibiotic prescribing patterns and sent them letters that compared their prescribing patterns with those of other doctors. This intervention, based on a behavioral concept called “social proof,” proved successful: BERT was able to reduce the number of antibiotic prescriptions by more than 125,000 over a six-month period.9

Partnerships. Another way many governments are using behavioral insights to develop effective policies is to partner with academia, nonprofits, and multilateral organizations. For instance, the World Bank’s Mind, Behavior, and Development Unit works closely with local governments worldwide on some of the biggest economic and social problems by evaluating behavioral patterns and designing appropriate interventions.10 In Tanzania, the World Bank, in partnership with a local mobile service provider, developed behaviorally informed text messages to encourage low-income individuals to save more; the highest savings achieved here was more than 11 percent.11

Next-generation nudges. Some governments have also begun transitioning to the next generation of nudges, which increasingly embed design thinking, data, and predictive analytics into government programs. Predictive models based on big data can be used to flag the issues most in need of attention, while behavioral insights can provide the tools to prompt the desired behavior change.12 Small, often inexpensive changes can yield outsized results. By leveraging big data and machine learning, government agencies can create prescriptive nudges, customized to provide the right nudge to the right person at the right time, thereby maximizing impact. Analogous to precision medicine, the “3D” trifecta of data, digital, and design can ultimately enable what might be called “precision engagement.”13

New Mexico’s Department of Workforce Solutions has applied these tools to tackle a thorny problem: claimants improperly collecting unemployment insurance benefits due to inaccurate disclosure of earnings and other information.14 Officials recognized that most improper claims were minor, rather than serious, scams. So, rather than taking the traditional (and expensive) approach of criminal enforcement, they used low-cost “pop-ups” and other nudges—customized using machine learning—to prompt more accurate disclosure.15 In the year after the smarter system went live, improper payments fell by half, and unrecovered overpayments have shrunk by almost 75 percent, saving the state almost US$7 million annually.16

While the application of behavioral insights has succeeded in accomplishing a variety of effective policy outcomes, there are certain risks associated with the approach. In some cases, government nudges may come off as overly paternalistic, or worse, manipulative. Richard Thaler says that whenever he autographs a copy of Nudge, he writes, “Nudge for good!” Good nudges can help individuals overcome natural human limitations to make better choices. In contrast, choice architecture can also be used in ways that manipulate or exploit our human limitations. (Some commercial nudges—“buy now, pay later!”—fall into this category.) Furthermore, poorly designed nudges may produce counterproductive results or unintended consequences—making thoughtful design and a commitment to testing and learning critical. Despite these concerns, nudge thinking has shown its effectiveness, and should be considered for any policy that involves human behavior.

Data signals

- More than 200 public entities worldwide apply behavioral insights.17

- In 2017, the Organisation for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD) published “the first-ever global collection of over 100 behavioral insights case studies from around the world and key lessons for public institutions.”18

- Since 2015, the GSA Office of Evaluation Sciences has completed more than 60 tests with more than a dozen agencies.19

- Dozens of nudge experiments have been conducted by the US Internal Revenue Service.20

- Approximately 780 projects have been undertaken by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) since its inception.21 The team has also conducted 99 trials in 37 US cities as part of the “What Works Cities” program.22

Moving forward

- Identify the ultimate objective of a policy, whether it’s to discourage rule-breakers or to encourage program buy-in. Behavioral insights can be applied if traditional approaches have failed to yield the desired outcomes in the past.

- Choose your nudges. Start with considering the outcomes you are seeking. What design factors may be influencing people’s behaviors? Are there social influences at play? What types of nudges might be appropriate? What is the choice architecture and default choice? Are there small barriers that discourage people from making better choices? What interventions can we design to improve outcomes?

- Test and assess the impact of the program—this can be crucial to its overall success.23 Find out what works for whom, why, and how to scale for maximum impact.

- Incorporate end-user insights. Check for any behavioral barriers to effective policy response. Reframe and redesign the policy or intervention based on the end-user insights.

Potential benefits

- Improve rule compliance;

- Increase engagement in public programs; and

- Better cost-effectiveness.

Risk factors

- Overbearing nudges may affect citizen autonomy;

- Poor design or lack of impact measures may yield unintended, possibly negative outcomes; and

- May adversely impact welfare for certain target groups.

Read more on how governments are applying behavioral science for better policymaking in the Behavioral economics and public policy collection.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collections

-

AI-augmented government Article5 years ago

-

Anticipatory government Article5 years ago

-

Cloud as innovation driver Article5 years ago

-

Introduction Article5 years ago

-

Innovation accelerators Article5 years ago

-

Government Trends 2020 Collection5 years ago