Obamacare and the changing health care landscape: Current health care trends has been saved

Obamacare and the changing health care landscape: Current health care trends Issues by the Numbers, August 2015

21 August 2015

Patricia Buckley

Patricia Buckley

With the last major legal challenge to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) settled, now comes the real test: Can the ACA help rein in one of the major drivers of rising health care costs—the cost of care per case?

With the last major legal challenge to the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a.k.a. Obamacare, recently settled by the Supreme Court, now is an appropriate time to examine current trends in health care. Even though not all of these trends are directly attributable to provisions of the ACA, they will determine the act’s ultimate costs and benefits. In particular, with growth in health care spending slowing and the number of people with access to health insurance rising, the stage is set to see whether the United States can become a more efficient producer and consumer of health care.

View related infographic

Click hereSpending growth has slowed but remains high

In 2013, the United States spent $2.9 trillion on health care.1This is the world’s highest cost per capita, double the per-capita health care spending of Canada.2 Unfortunately, this high level of spending is not producing superior health outcomes. While life expectancy at birth is over 80 years in most of the industrialized nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the OECD groups the United States with countries such as Chile and the Czech Republic that have a life expectancy of under 79 years. And the trend is moving in the wrong direction: In 1970, US life expectancy was one year above the OECD average; it is now more than one year below the average.3

One trend is positive: Growth in US health care spending has slowed over the last few years.

One trend is positive: Growth in US health care spending has slowed over the last few years, ranging from 3.6 percent and 4.1 percent per year from 2008 to 2013, down from an annual average of 6.3 percent from 2003 to 2008 and an annual average of 8.0 percent from 1998 to 2003.4 Indeed, since 2009, US health care spending as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) has held steady at 17.4 percent, taking a post-recession break from earlier increases (figure 1). However, even with periods of relative stability, health care costs have grown over the last 20 years by 4.0 percent of GDP.

A recent study by researchers at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) disaggregates the growth in per-capita health care spending into three components: medical prices, age and sex factors, and a residual growth component that is attributable to use and intensity. As shown in figure 2, even though the overall growth rate stayed fairly steady from 2009 through 2013, the blend of cost drivers changed dramatically. From 2009 through 2011, rising medical prices accounted for most of the total increase, while increased use/intensity was the driving factor in 2012 and 2013. In the three-year period from 2009 through 2011, medical prices drove expenditure growth as they did during the 2004-to-2008 period; however, utilization rates fell, largely as a result of “a significant loss of private health insurance coverage, a decline in total investment in medical structures and equipment as well as changes in types of investments, and reduced demand for health care services as a result of financial uncertainty caused by the recession.”5 Residual use and intensity rebounded in 2012 and 2013 as the US economy began to recover and the ACA’s provisions to expand Medicaid and increase access through exchanges took effect. The CMS study’s researchers attribute the slowdown in prices, in part, “to the ACA-mandated productivity adjustments to Medicare fee-for-service payments, the budget sequestration, and the impacts of the ACA-mandated medical loss ratio and rate reviews on the net cost of private health insurance.”6

How the money is spent

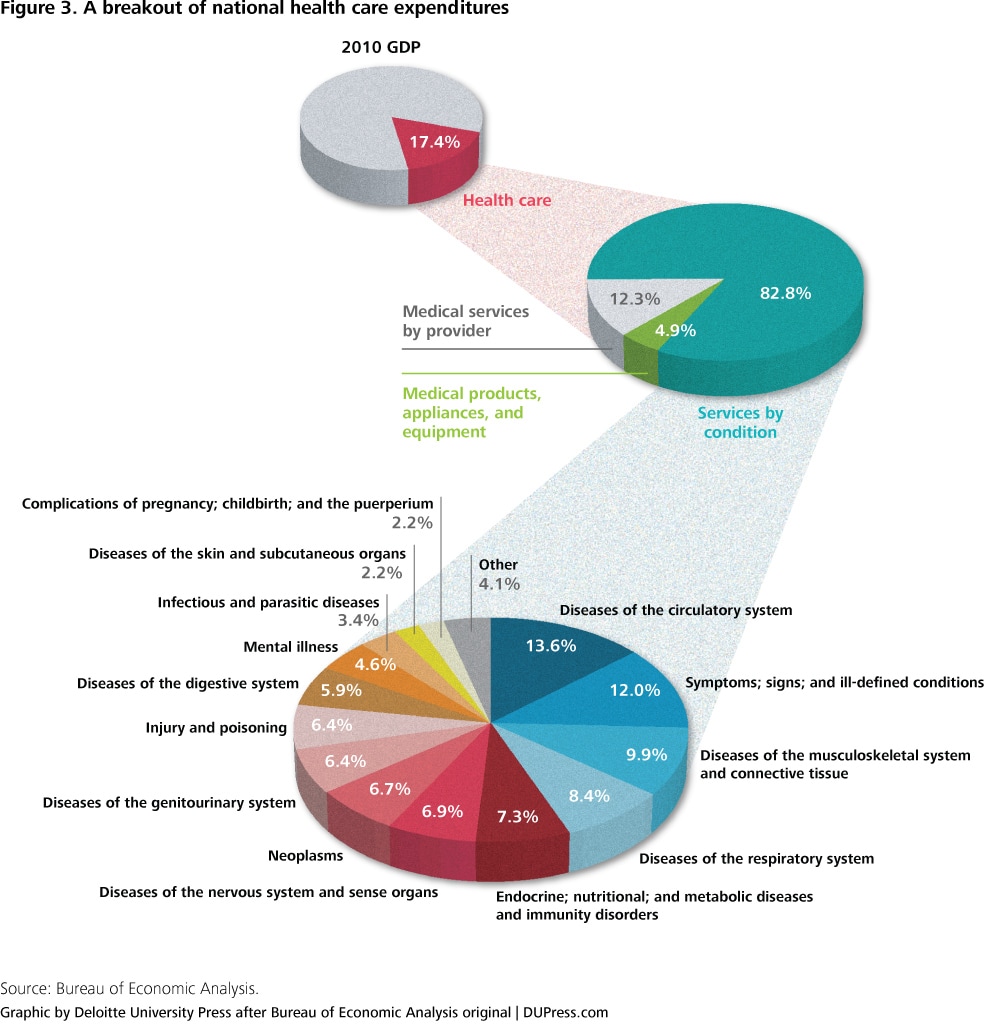

Traditional breakouts for health care expenditures consider where and on what products the money is spent (for example, hospitals, doctor offices, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices). However, this year, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released an alternative measure that allocates health care’s 17.4 percent of GDP by disease, as illustrated in figure 3. In 2010, spending on circulatory issues and the general “symptoms” category, which includes preventative care and allergies, together accounted for just over one-quarter of all costs allocated by condition.7

This new categorization helps both providers and policymakers by more clearly indicating the drivers of health care cost increases. A look at the numbers reveals that a higher cost per case accounted for 73 percent of the per-capita spending growth between 2000 and 2010, with a rise in the number of treated cases contributing 27 percent.8 Thus, different methodologies notwithstanding, the CMS study and this new BEA satellite account agree that increased intensity—or a higher cost per case—is a major driver of health care cost growth.

Paying for health care

Health care is unique among consumer goods and services in the separation that exists between payers, decision makers, and ultimate beneficiaries. However, this situation is changing, even for insured patients, as more plans now carry higher co-pays and/or deductibles. The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions’ 2015 health care consumer survey shows consumer engagement trending upward on three sets of measures, supporting individuals’ transformation from “passive patients and purchasers” to “active health care consumers”: partnering with providers in making treatment decisions, tapping online resources for information on treatments and doctors, and using technology to track personal health.9

Even with these shifts, 72 percent of health care costs are covered by insurance—a combination of private insurance and Medicare, Medicaid, and other government insurance plans. While most individuals covered by private plans do bear some of the cost of their own care (which can be substantial or even represent the total cost), nationally, the actual out-of-pocket cost directly related to care received is only 12 percent (figure 4).10

The payment source varies substantially by type of service, as shown in figure 5. For example, only 3.5 percent of the cost paid to hospitals is “out of pocket,” while the comparable figure for visits to the dentist is 42.5 percent.

Insurance coverage has expanded

The ACA has several provisions aimed at increasing insurance coverage, including the expansion of Medicaid, the establishment of state health care marketplaces, and the provision of subsidies to individuals to help them afford coverage through the marketplaces.

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion provision gives states federal funding to expand their Medicaid programs to cover adults under 65 with income up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level regardless of disability, family status, financial resources, and other factors that eligibility guidelines usually take into account; children age 18 and under in households up to that income level or higher are eligible in all states.11 At present, 29 states plus the District of Columbia have accepted Medicaid expansion, two are still deciding, and 19 have declined.12

The ACA also called for the establishment of state-level health care marketplaces to allow individuals and families the opportunity to purchase health insurance at group rates. States had a choice of setting up their own marketplace or deferring to the federal government. Currently, 13 states plus the District of Columbia have state-based marketplaces, three have federally supported marketplaces, seven have state partnership marketplaces, and 27 have federally facilitated marketplaces.13 To aid citizens purchasing health care plans from a marketplace, the ACA provides tax credits for those making under 400 percent of the federal poverty level, as well as subsidizing mid-level insurance plans to those making under 250 percent of the federal poverty level. A June 25, 2015 Supreme Court ruling confirmed the federal government’s authority to offer subsidies to those purchasing insurance through federally run marketplaces;14 loss of this feature would have jeopardized the program’s viability.

From September 2013 to February 2015, 22.8 million Americans became newly insured and 5.9 million lost coverage, for a net gain of 16.9 million more insured.

According to the RAND Corporation, US insurance coverage has increased across all types of insurance since the major provisions of the ACA took effect, with a net total of 16.9 million people becoming newly enrolled between September 2013 and February 2015.15The RAND study includes a breakdown of type of coverage, including the surprising observation that the largest source of new coverage is traditional employer-sponsored plans. The primary findings include:

- From September 2013 to February 2015, 22.8 million Americans became newly insured and 5.9 million lost coverage, for a net gain of 16.9 million more insured.

- Among those newly gaining coverage, 9.6 million people enrolled in employer-sponsored health plans, followed by Medicaid (6.5 million), the individual marketplaces (4.1 million), non-marketplace individual plans (1.2 million) and other insurance sources (1.5 million).

- Among the 12.6 million Americans newly enrolled in Medicaid, 6.5 million were previously uninsured and 6.1 million were previously insured.

- An estimated 11.2 million Americans are now insured through new state and federal marketplaces created under the ACA, including 4.1 million who are newly covered and 7.1 million people who transitioned to marketplace plans from another source of coverage.

- The study also estimates that 125.2 million Americans—about 80 percent of the non-elderly population that had insurance in September 2013—experienced no change in their source of insurance during the period.16

Employer cost for insurance

The ACA’s employer penalties for failure to provide affordable coverage come into effect this year for employers with 100 or more employees and in 2016 for employers with 50 or more employees. Most companies should see little impact, considering that in 2013, 95.7 percent of private-sector employers with 50 or more employees offered health insurance.17 However, the ACA sets out criteria for minimum coverage and/or affordability, with penalties for failing to meet these criteria, and some employers’ insurance plans fall short.

As shown in figure 6, the cost per employee-hour for health benefits has declined recently; analysts can only guess whether and by how much the new coverage and affordability rules will affect this cost.

The ACA’s total impact is as yet unclear, as various parts of the legislation that will affect costs and benefits will continue to roll out in the months and years ahead.

Looking forward

The ACA’s total impact is as yet unclear, as various parts of the legislation that will affect costs and benefits will continue to roll out in the months and years ahead. For example, the ACA provides for a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (“Innovation Center”), with a $10 billion budget over 10 years. The Innovation Center is tasked with testing innovative health care payment and service-delivery models, with the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) expenditures.18 Many of these models emphasize value-based care rather than the traditional fee-for-service. If successful, these new models could provide more effective care at lower prices.19

Remaining parts of the ACA that are still awaiting implementation include:

- An increase in the federal match for CHIP of 23 percent up to a cap of 100 percent (scheduled for October 2015).

- Permission for states to form health care choice compacts allowing insurers to sell policies in any state participating in the compact (scheduled for January 2016).

- The institution of an excise tax on insurers of employer-sponsored health plans with aggregate expenses that exceed $10,200 for individual coverage and $27,500 for family coverage (the “Cadillac tax”; scheduled for January 2018).20

As a mechanism for increasing insurance coverage, the ACA has been largely successful (albeit some argue that a lower-cost system could have been devised). Another important test, however, will be the ACA’s impact on reining in the cost or intensity of use per case—a major driver of rising health care costs—and obviously, we won’t know whether the system is functioning as intended until more information comes in over the coming months and years. Cost reduction efforts are key, since, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost to fund exchange or marketplace subsidies and Medicare and CHIP expansion ($1.7 trillion) will be significantly higher than the revenue brought in by fines on employers and the uninsured and by excise taxes on high-premium insurance plans ($540 billion) over the next 10 years.21 However, CBO estimates of ACA’s cost cannot include some (potentially sizable) benefits that the legislation aims to generate, such as the CMS Innovation Center, that will not be felt for years but that could result in more effective and efficient spending on health care in the United States.