The power of platforms has been saved

The power of platforms Part of the Business Trends series

16 April 2015

Properly designed business platforms can help create and capture new economic value and scale the potential for learning across entire ecosystems.

Ecosystems are dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create new value through increasingly productive and sophisticated models of both collaboration and competition. Read more about our view of business ecosystems in the Introduction.

Ecosystems are dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create new value through increasingly productive and sophisticated models of both collaboration and competition. Read more about our view of business ecosystems in the Introduction.

Properly designed business platforms can help create and capture new economic value and scale the potential for learning across entire ecosystems.

Overview

EXPLORE

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2015 report.

When Marc Merrill and his partner designed the online game League of Legends and founded a company, Riot Games, in 2009 to bring it to market, they didn’t only have in mind to create a new product for the gaming world. Their strategy was to build a platform. Already, that platform has become a very valuable one. Start with the game itself: 67 million people play it each month,1 generating some $1 billion dollars in annual revenue for the company.2 These gamers, who may be sitting alone in their dorm rooms but who, online, join up as teams to do battle, all play for free; Riot Games makes its money when, having drawn everyone into its designed environment, it finds other ways to capitalize on their presence. More recently, the company extended its platform to the offline world, creating live events in which League of Legend teams compete in tournaments in front of live spectators. It doing so, it launched what is now the fastest-growing part of the sports industry: e-sports.

Riot Games’ still evolving strategy is just one example of a trend we see all around us today, and not only among companies that were “born digital.” Everyone, it seems, is thinking in terms of platforms. That is, they are recognizing that, no matter the market, there is money to be made in providing layers of capabilities and standards that other players in that market can tap into and use to interact more efficiently. Popular platforms—a classic example being the iTunes application program—allow the participants on them to create and capture value for themselves, while also (thanks to network effects) yielding strong returns for the platform builder.3 Every participant must abide by the rules of the platform but is otherwise not answerable to any other player in it, including the platform originator.

The trend we’ll describe below, however, is likely more nuanced than the simple observation that many more firms are devising platform strategies. Managers’ familiarity and experience with platforms have reached the stage that they are increasingly designing them, or taking advantage of their existence, for particular kinds of gains. As we’ll discuss in more detail, many firms are employing noticeably different tactics depending on whether they see a platform as a way to improve performance (by focusing on what they do best), grow their footprint (by leveraging capabilities that in the past they would have had to own), innovate (drawing on that vast majority of smart people who aren’t strictly in their employ), or capture more value. Looking ahead, we anticipate that smart managers will refocus their platform strategies again—on the deliberate pursuit of the learning advantages that platform participation uniquely affords.

What’s behind this trend?

In one sense, platforms are nothing new. If we define them as layers of infrastructure that impose standards on a system in which many separate entities can operate for their own gains, then clearly any nation’s railway system, once it standardizes on track gauge, counts as a platform. Likewise, its phone system, and its shipping system, having converged on global standards for pallets and shipping containers.

But platforms have grabbed unprecedented attention in the digital era.4 This is thanks partly to a gold rush mentality, since the advent of that ultimate platform of our age, the Internet, spawned opportunities for new, electronic platforms to be built in every realm of commerce.

The deeper reason that platforms have lately captured so many business leaders’ imaginations is that they enable the “pull-based” approaches which have long been seen as the future of serving customers profitably.5 In the past, sellers have been limited by the economics of production and distribution to “push-based approaches,” meaning that they simply made an efficient batch size of what they sold and foisted it onto the marketplace. This of course meant investing effort into anticipating what the customer demand might be, using that to create a sales forecast, and then procuring the right resources and people to produce the appropriate quantity of goods. A push-based approach is very efficient if the forecast is accurate—and can at least be profitable if, failing that, the marketer is able to alter demand with its pricing and advertising. But in today’s world, those have become much bigger “ifs.”

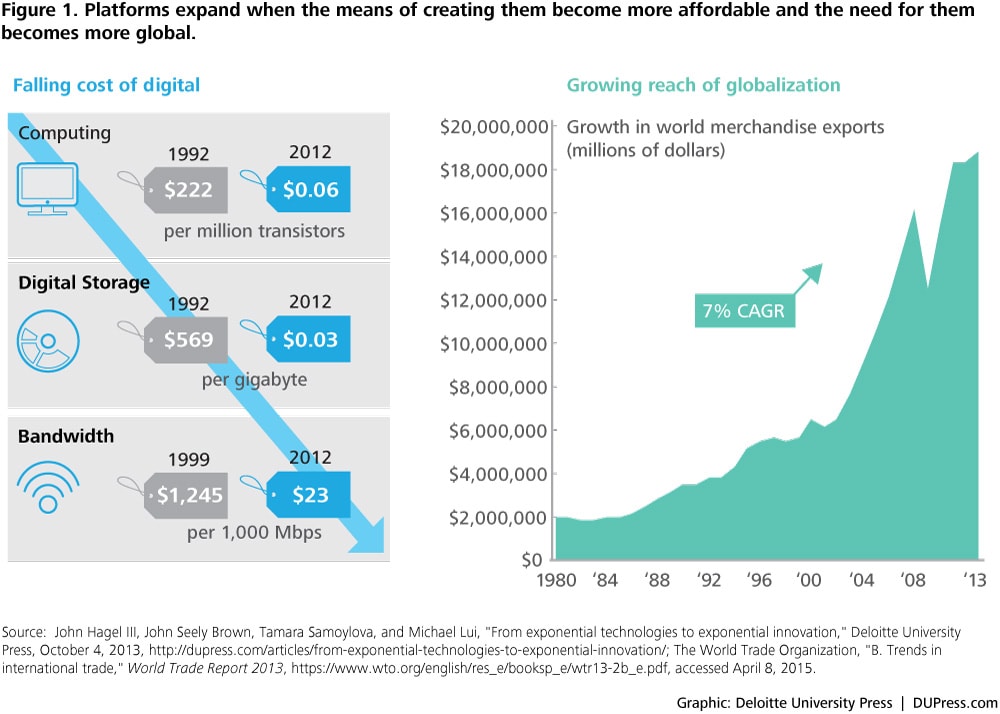

Two fundamental, long-term trends, which have been transforming the business landscape for the past few decades and still have far to go, are essentially eliminating the conditions in which push-based approaches can work. These two forces are the deployment of digital technology infrastructures, and the long-term public policy trend globally toward economic liberalization. The cost of three core digital technology capabilities—computing power, data storage, and bandwidth—relative to their performance has been decreasing exponentially and at a faster rate than that of previous technological advances such as electricity and telephones.6 At the same time, global trade has increased at about 7 percent per annum on average—or twice the growth rate of global GDP—for almost three decades.7 Together, digitization, for shorthand, and globalization produce what researchers at Deloitte’s Center for the Edge call “The Big Shift.”8 It’s a period of time in which the foundations that everything is built upon are reshaped, and thus everything changes.

As the Big Shift plays out, it is becoming newly possible—and therefore newly imperative—for sellers to move to pull-based approaches. These reorient operations such that nothing happens until actual demand signals are received from real buyers. Students of lean manufacturing and pull-based inventory systems know the theory and have seen the advantages that can be gained from this reorientation.9 But most of the potential of pull-based systems has yet to be realized, because these early efforts have been applied only to small numbers of companies within well-defined supply chains. Market-spanning platforms offer ways to take these pull-based approaches to scale.

The trend

We have now reached the point where most well-read business leaders know the language of platforms. They can recognize them where they exist and understand the value they create, both for the platform creator and the participants. They have also seen the tremendous power of the platforms that have proved most scalable. Some platforms already encompass thousands and, in many cases, millions of independent participants, who benefit as a result from enhanced leverage, specialization, and flexibility.

Examples of platforms are all around us. Take InnoCentive, the open innovation company that allows seekers of specific engineering, science, and other kinds of solutions to connect with expert solvers. It’s a pull platform that allows companies to get answers to their most pressing research problems, often from unexpected sources. Li & Fung provides yet another example of a pull platform in business. The company orchestrates complex supply networks for apparel designers, relying on a global pull platform to draw out over 15,000 business partners when needed and where needed to ensure rapid and effective response to the rapid and unexpected shifts in demand for items of apparel.10 All these platforms are wonderfully scalable; rather than becoming unwieldy with greater numbers of participants, they become only more capable and valuable.

What’s a platform?

Platforms help to make resources and participants more accessible to each other on an as-needed basis. Properly designed, they can become powerful catalysts for rich ecosystems of resources and participants. A couple of key elements come together to support a well-functioning platform:

- A governance structure, including a set of protocols that determines who can participate, what roles they might play, how they might interact, and how disputes get resolved.

- An additional set of protocols or standards is typically designed to facilitate connection, coordination, and collaboration.

Platforms are increasingly supported by global digital technology infrastructures that help to scale participation and collaboration, but this is an enabler, rather than a prerequisite, for a platform. In the early development of Li & Fung’s platform for the apparel industry, for example, it relied on very limited technology, largely the telephone and fax machine, and instead focused on defining the protocols and standards that made it possible to deploy a loosely coupled, modular approach to business process design.11

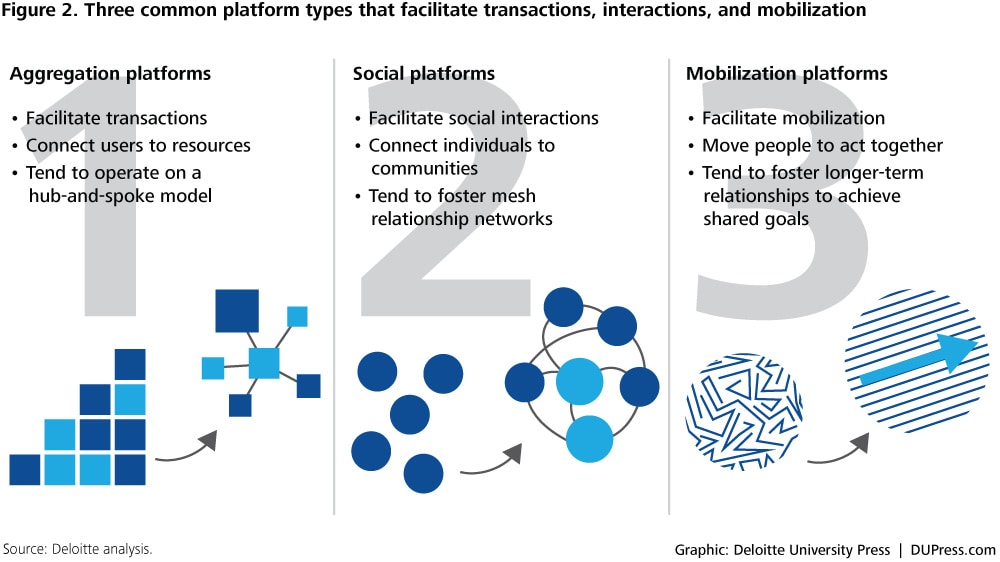

Enough platforms have been deliberately designed at this point that it is useful to categorize them into types. The three common types in existence today help their participants do three different things well.

Aggregation platforms bring together a broad array of relevant resources and help users of the platform to connect with the most appropriate resources. These platforms tend to be very transaction- or task-focused—the key is to express a need, get a response, do the deal, and move on. They also tend to operate on a hub-and-spoke model. That is, all the transactions are brokered by the platform owner and organizer. Within this category there are three sub-categories. First, there are data or information aggregation platforms like stock performance databases for investors or scientific databases. Second, there are marketplace and broker platforms like eBay, Etsy, and the App Store online store,12 which has facilitated 85 billion app downloads as of October 2014.13 These provide an environment for vendors to connect more effectively with relevant customers wherever they might reside. In a growing number of cases, these platforms draw out resources that were previously not available to others. For example Airbnb has created a platform that has grown more than tenfold, from 50,000 to 550,000 listings, in less than four years,14 by encouraging people to make spare rooms or parts of their home available to travelers and thus creating a market for these resources. And third, there are contest platforms like InnoCentive or Kaggle where someone can post a problem or challenge and offer a reward or payment to the participant who comes up with the best solution.

Social platforms are similar to aggregation platforms in the sense of aggregating a lot of people—think of all the broad-based social platforms we’ve come to know and love: Facebook and Twitter are leading examples. They differ from aggregation platforms on some key dimensions. First, they end up building and reinforcing long-term relationships across participants on the platform—it’s not just about doing a transaction or a task but getting to know people around areas of common interest. The pull of these platforms is irresistible to many—witness the fact that US adult users spend an average of 42.1 minutes per day on Facebook and 17.1 minutes on Twitter.15 Second, they tend to foster mesh networks of relationships rather than hub-and-spoke interactions—people connect with each other over time in more diverse ways that usually do not involve the platform organizer or owner.

Mobilization platforms take common interests to the level of action. These platforms are not just about conversations and interests; they focus on moving people to act together to accomplish something beyond the capabilities of any individual participant. Because of the need for collaborative action over time, these platforms tend to foster longer-term relationships rather than focusing on isolated and short-term transactions or tasks. But a key focus here is to connect with, and mobilize, a given set of people and resources to achieve a shared goal. The participants are often viewed as “static resources”—they have a given set of individual capabilities and the challenge is to mobilize these fixed capabilities to achieve the longer-term goal. There are many different forms of mobilization platforms. In a business context, the most common form of these platforms are “process network” platforms that bring together participants in extended business processes like supply networks or distribution operations that help to select and orchestrate participants who need to collaborate in flexible ways over time. Li & Fung, the global sourcing company mentioned earlier, offers a prime example of this kind of platform although there are many other examples spanning a broad range of industries, including motorcycles, financial services, diesel motors, and consumer electronics. A little further afield (because they are not profit-making enterprises) would be open source software platforms like Linux or Apache. Even further afield would be mobilization platforms that support social movements, such as in the Arab Spring movement.

Implications

An implication for management teams of the rise of platforms is that, in their work to devise strategies for future success, they should explicitly consider what their “platform plays” will be. Some will identify useful platforms that have yet to be established, and choose whether to create those unilaterally or by forming consortia. All should survey the platforms arising in their markets and consider the degree to which they will be active participants in them.

As we see management teams addressing such questions today, the strategic choices they make are based on the four major kinds of benefits they expect to gain from platforms. Depending on the relative emphasis they place on performance improvement, leveraged growth, distributed innovation, and shaping strategies, they gravitate toward some platform opportunities more than others.

Performance improvement

For some, the most attractive platform is one that allows its participants to focus on the activities that they do exceptionally well and to shed other activities to others to whom they connect through the platform. As an example, many small, focused product vendors and merchants now rely on Amazon’s selling platform to handle a variety of complex and scale-intensive tasks, including website management and fulfillment operations. The beauty of such platforms is that the partners who pick up others’ non-core work are entities who themselves have chosen to specialize in those activities, and are likely to perform them better. The net result of every activity being handled by a player focused tightly on it is overall performance improvement for all participants.

Leveraged growth

Firms hoping to expand the footprint of their businesses have traditionally opted for either organic growth or growth by acquisition. Some platforms open up a third path. They allow participants to connect with the capabilities of others and make them available to their customers in ways that create significant value for the platform participants and the customers. Li & Fung has grown into a $20 billion global company in the supply network business even though its sourcing business does none of the actual production itself.16

Distributed innovation

Some companies are focusing on the use of platforms to tap into creative new ideas and problem-solving from a broad and diverse range of third parties through the use of contests that provide rewards for coming up with the best approaches to major challenges or opportunities. XPrize has helped spur innovation in a broad range of arenas, including space travel, automobiles, and oil spill removal. With a belief that “no one nation, gender, age group, or profession has a monopoly on creativity or intelligence,” XPrize’s ongoing Google Lunar XPrize challenge drew talented teams from more than 15 different countries as diverse as Israel and Japan.17

Shaping strategies

For the most strategically ambitious of firms, an exciting potential associated with some platforms is the ability to change how an entire marketplace operates—and capture more value by doing so. Think back, for example, to the dawn of the credit card business, when Dee Hock founded Visa. By persuading banks to rely on a shared utility for the back-office processing of credit card transactions—a platform—he managed to restructure an entire industry. For the banks, the platform helped turn a money-losing new product into a profitable business. Today, there are a growing number of opportunities to restructure entire markets and industries by designing new platforms and offering powerful incentives to motivate third parties to participate on them. These are very effective because they mobilize investment by a broad range of other participants rather than requiring the shaper to put all its own money on the table.

All of these are excellent reasons to participate in platforms, and most firms will be able to pursue more than one of these goals simultaneously. However, a clear sense of which are the priority goals—perhaps gained in a focused discussion during a strategic offsite meeting—can point to the best platform plays for any specific firm.

What’s next?

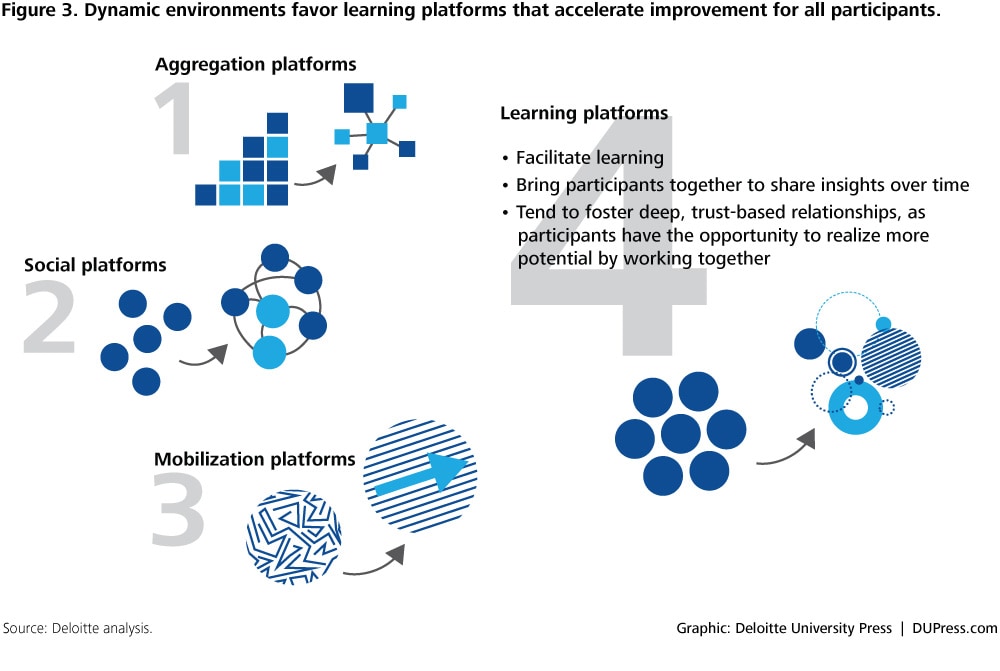

We discussed above three common kinds of platforms already in existence, based on what the participants in them are trying to do. Some want only to transact business, and use aggregation platforms to do that; others want to socialize, or to mobilize, and there are platforms well designed for them, as well.

But in a world of mounting performance pressure, we should also expect a fourth form of platform to become prominent. Dynamic and demanding environments favor those who are able to learn best and fastest. Business leaders who understand this will likely increasingly seek out platforms that not only make work lighter for their participants, but also grow their knowledge, accelerate performance improvement, and hone their capabilities in the process.

Very few examples of learning platforms exist in business yet, but we can find very large-scale learning platforms in arenas as diverse as online war games (for example, World of Warcraft) and online platforms to help musicians develop and refine their remixing skills (for example, ccMixter). They have also emerged in a broad array of extreme sports arenas, including big-wave surfing and extreme skiing.18

Your best platform strategy: Occupy an influence point

Platforms can be effective vehicles to create new value. The risk is that they might also undermine the ability of individual companies to capture their fair share of the value being created, especially if they do not own the platform. By creating far more visibility into options and facilitating the ability of participants to switch from one resource or provider to another, platforms can commoditize business and squeeze the margins of participants.

The greatest opportunities for value capture on platforms require an understanding of influence points that can create and sustain sources of advantage and make it feasible to capture a disproportionate share of the value created on the platform.19 Influence points tend to emerge whenever and wherever relationships begin to concentrate on platforms. By having privileged access to a larger and more diverse array of knowledge flows, the company occupying an influence point has an opportunity to anticipate what’s going to happen by seeing signals before anyone else does. That company is also better positioned to shape these flows in ways that can strengthen its position and provide greater leverage. When you’re in the center of flows, small moves, smartly made, can indeed set very big things into motion.

Where would these influence points tend to emerge on platforms? These points often provide significant and sustainable functionality to the broader platform or ecosystem—for example, the broker position in a market platform. It’s even better if the functionality of these influence points evolves rapidly over time because it creates incentives for other participants to stay in close contact with the occupier of the influence point.

Enough examples exist to see that these platforms have a distinctive configuration known as “creation spaces.” Their primary unit of organization is a small team or work group that takes on particular performance challenges. The participants in these groups work closely together over time to come up with creative new ways to address evolving performance challenges. The emphasis on small teams or work groups is essential because the focus is on a powerful form of learning that involves accessing tacit knowledge. This in turn requires the formation of deep, trust-based relationships. These relationships evolve quickly in small teams or workgroups but are very challenging to scale. The second key element of these platforms is that they provide participants with ways to connect with each other beyond the individual team or workgroup to ask questions, share experiences, and get advice. In other words, they scale the potential for learning far beyond the individual group.

As with social platforms and mobilization platforms, learning platforms critically depend on the ability to build long-term relationships rather than simply focusing on short-term transactions or tasks. Unlike the other platforms, though, learning platforms do not view participants as “static resources.” On the contrary, they start with the presumption that all participants have the opportunity to draw out more and more of their potential by working together in the right environment.

The good news is that any of the three current forms of platforms—aggregation, social, and mobilization—have the potential to evolve into learning platforms. The companies that find ways to design and deploy learning platforms will likely be in the best position to create and capture economic value in an increasingly challenging and rapidly evolving business environment.

My take

By Peter Schwartz

Peter Schwartz is senior vice president for strategic planning at Salesforce.com, author of The Art of the Long View, and a frequently sought commentator on forces shaping the future of business.

Platforms today power learning and innovation at the speed of business by providing collaborative and sometimes exponentially productive spaces for value creation. At Salesforce, we take this model seriously, not just by building our own platform and apps but by opening our platform to millions of partners, developers, and customers, allowing them to customize and layer on top of our core.

Platforms today power learning and innovation at the speed of business by providing collaborative and sometimes exponentially productive spaces for value creation. At Salesforce, we take this model seriously, not just by building our own platform and apps but by opening our platform to millions of partners, developers, and customers, allowing them to customize and layer on top of our core.

In fact, one way to think about the latest release of Salesforce 1, our flagship product, is as a set of apps that provides our customers with a way to write their own apps. All of that must be enabled by some pretty sophisticated code as the underlying glue. But most of our users are never going to touch that inner wiring. What they will touch—and what we want them to own and build on as their own—is a set of extensions upon the centerpiece we provide. When customers are given the tools, we are often amazed at the breakthroughs.

For example, I like to tell the story of a major food logistics company building a Salesforce extension that transforms the jobs of truck drivers, who are now a critical point of connection, stringing delivery, sales, and relationship management functions from the final customer all the way back to the source. When we enable that kind of transparency, we are changing the nature of jobs. We now have a customer that not only loves Salesforce, but also owns and operates a deeply personalized version of Salesforce 1 that allows it to see things previously hidden in the most distant pockets of its value web.

And when a client writes a super-interesting extension of the core Salesforce platform, we might look for new ways to complement it by adding, say, robustness, or lightness, or ease-of-use. In other instances we might seek to license the customer’s functionality. Or, increasingly, we look to invest in some of the more exciting prospects, thus building an R&D investment portfolio without the failure rates so common when you incubate from scratch.

In a world of business ecosystems, loyalty may be the final and most important of the currencies exchanged. For Salesforce, a vibrant platform ecosystem of customer developers, apps, and support services, one that has loyalty and mutual commitment as its life blood, is our engine of growth. A lot of the value that is created on the Salesforce platform is directly owned by our partners and customers, and that’s exactly as it should be. We think of the shared value that is collectively created as the adhesive that binds the Salesforce platform to the broader ecosystem in which the client, now co-evolving with Salesforce, competes and generates economic returns.