Supply chains and value webs has been saved

Supply chains and value webs Part of the Business Trends series

16 April 2015

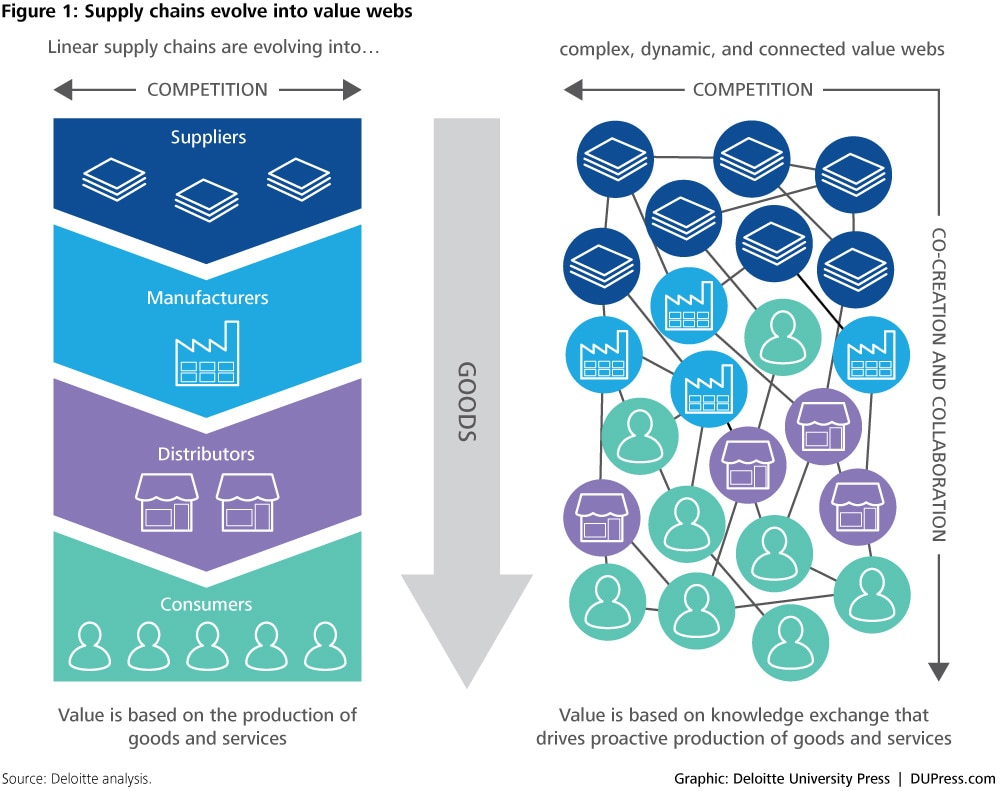

Supply chains are increasingly becoming value webs that span and connect whole ecosystems of suppliers and collaborators; properly activated, they can play a critical role in reshaping business strategy and delivering superior results.

Ecosystems are dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create new value through increasingly productive and sophisticated models of both collaboration and competition. Read more about our view of business ecosystems in the Introduction.

Ecosystems are dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create new value through increasingly productive and sophisticated models of both collaboration and competition. Read more about our view of business ecosystems in the Introduction.

Supply chains are increasingly becoming value webs that span and connect whole ecosystems of suppliers and collaborators; properly activated, they can play a critical role in reshaping business strategy and delivering superior results.

Overview

EXPLORE

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2015 report.

Over the last few decades, supply chain professionals have helped transform the business environment. They have contributed to accelerated globalization by directly connecting actors in emergent and developed economies. They have enabled many major corporations to become nimbler and leaner by focusing on what they themselves do best, while carefully constructing external arrangements for the rest. Supply chain professionals have helped reduce costs, improve efficiency, and substantially enhance operational performance. And they have altered the basis of competition—as one scholar has suggested, increasingly today, “Companies don’t compete—supply chains do.”1

By mastering the management of assets that exist outside the traditional boundaries of the firm, the supply chain profession has also helped forge the dynamic, collaborative, industry-transcending world of ecosystems described throughout this report. As the era of the vertically integrated corporation has waned, new and more fluid alternatives have proliferated. But to date these arrangements have typically replaced ownership with “control.”2 In ecosystems, influence will need to be achieved across increasingly complex networks—through relationships, collaboration, and co-creation. Many traditional supply chains are becoming increasingly agile, adaptive, and resilient, and are supporting faster and more flexible responses to the changing needs of customers. Today’s supply chains contain growing varieties of players interacting in interdependent and often indirect ways.3

In fact, many “supply chains” appear to be evolving into “value webs,” which span and connect whole ecosystems of suppliers and collaborators. Properly activated, these value webs can be more effective on multiple dimensions—reducing costs, improving service levels, mitigating risks of disruption, and delivering feedback-fueled learning and innovation. This is likely to accelerate as new technologies generate more data, provide greater transparency, and enable enhanced connectivity with even tiny suppliers and partners. The shift can create new challenges for the supply chain profession—but also extraordinary opportunities to play an even more central strategic role in shaping the future of enterprise.

What’s behind this trend?

A set of powerful developments have worked together to help transform the business environment, changing how supply chains are configured, further heightening their strategic significance for many firms, and creating new leadership imperatives for the years ahead.

First, advancing information and communications technologies drastically reduced the transaction costs of dealing with outside entities, so that in short order, many assets that had made sense to own and activities traditionally performed in-house were now often better sourced from external suppliers. The general loosening of corporate dependence on ownership of key assets contributed to the activation of many new external resources and capabilities—and an explosion of new actors ready and able to contribute.

This technological enablement of inter-firm coordination has coincided with a long-term political movement: trade liberalization by many nations around the world. Together, the two forces enabled the offshoring, global outsourcing, and foreign market entries that helped create the new global economy. The leading firms of mature economies moved rapidly to globalize their operations, many of them with an eye to a future when all the growth of the world’s population—the next billion people—would be in emerging economies.4 Meanwhile, many businesses in less mature economies gained the opportunity to grow and join the global economic mainstream.

Leading firms everywhere soon realized there was a “sweet spot” to be found by effectively marrying globalization to “localization.” Nestlé, for example, declares that “food is a local matter,” and operates its networks according to a basic principle: “Centralize what you must, but decentralize what you can.”5 The Coca-Cola Company works to strike a similar balance. One commentator describes its strategy as “mingling global and local… utilizing local suppliers and local bottlers, employing local people, and addressing local culture and taste.”6 For many operations managers, such goals call for complex, multifaceted enhancements of activities taking place at multiple locational levels.

Today, new waves of technology are accelerating these already established shifts. Continuous innovation and global dissemination of new technologies and tools are directly enabling new connectivity, collaboration, and co-creation across multiple businesses. The rise of the Internet of Things—which connects increasingly smart products—is greatly enhancing the creation of and access to data, and producing ever-increasing transparency. Substantial technological changes unfolding today in manufacturing, including 3D printing and new robotics, are set to transform many production processes and may significantly disrupt today’s distribution models.

The speed and scale of these changes are creating new opportunities for many supply chain professionals—and also putting increased pressure on them to adapt. Their role is expanding far beyond enhancing performance by getting essentially the same things done, but differently and elsewhere. Their focus is extending beyond continuous improvement of existing operations. Instead, these professionals are being positioned as increasingly strategic leaders discovering fundamentally different ways of creating new value, driving continuous innovation and learning, and sustaining enterprise growth.

The trend

Having helped transform the operating and performance models of most major enterprises over the last few decades, many supply chains are now playing an even more central strategic role. They are helping lead their businesses into the dynamic, hyper-connected, and collaborative world of ecosystems. In doing so, many are now creating and leading more complex systems perhaps better characterized as value webs. The word “chain” has a powerful metaphoric logic that captures well a series of discrete links by which goods are bought, have value added to them, and are sold to the next value-adder—up until an end buyer consumes them. This remains of critical importance. However, increasingly, value is being created not only within firms, but in the rich interactions between them. Linear sequences of procurement are increasingly supplemented by more iterative and innovation-oriented collaborations.

To be sure, in a world of value webs, the essential goals of traditional supply chain management do not go away. But they are often augmented by new imperatives—like learning, agility, and renewal. Collaboration is an addition to, not a replacement of, traditionally more closed, contractual arrangements. Clear commitments to meet rigorously monitored standards and service-level agreements will remain critical. But to claim the benefits of an increasingly fluid and interdependent value web, leaders should surround their contracts with trust; build on transactions and one-time deals to cultivate long-term relationships and mutual learning; combine the power of control with the potential of co-creation; make sure that defined, fixed standards do not create barriers to valuable innovation and co-evolution; and not only leverage leading practices, but also aim to create “next practices.”

Some leading companies have explicitly adopted hybrid approaches to embrace such dualities. In one frequently quoted example, Chinese motorcycle manufacturer Dachangjiang deliberately pursued both value web and supply chain arrangements by breaking its design into multiple modules, awarding several suppliers responsibility and substantial latitude for each, and actively encouraging collaboration between them to promote innovation, while also imposing aggressive performance targets regarding pricing, quality, and timing of production.7

Just as most businesses have already learned how to activate and deploy assets they don’t own, they are now becoming increasingly adept at doing so with assets they don’t control, either. The 2015 Deloitte Supply Chain Leadership Survey confirms the value of gaining skills that promote influence. It finds that “leaders” distinguish themselves from “followers” in several areas. They are much more aggressive at using technical capabilities and powerful new technologies, like supplier collaboration and risk analytics, which can be critical in complex, dispersed networks (see figure 2). Leaders also tend to support diversity and inclusion and manage global and virtual teams significantly better than their peers (see figure 3). They are usually more adept at working with others: 80 percent of surveyed leaders rate their ability to negotiate and collaborate with partners highly, compared to less than half of followers.8 These greater abilities and attitudes reflect in the bottom line: 73 percent of surveyed leaders reported financial performance significantly above their industry average, in contrast to less than 15 percent of followers.9

Implications

Value webs are characterized by complex, connected, and interdependent relationships, where knowledge flows, learning, and collaboration are almost as important as more familiar product flows, controls, and coordination. To lead and secure advantage in this increasingly organic and networked environment, leaders will likely have to focus on three core developmental priorities.

Engagement with more, often smaller, players

The emergence of value webs is enabling the conditions for small, highly focused suppliers to proliferate in global supply chains. Important and complex capabilities increasingly involve deep specialization that often flourishes in smaller, tightly niched firms. Barriers to entry are generally declining. Young, nimble, and entrepreneurial firms frequently have innovation advantages. Many of the best and brightest of the Millennial generation are showing themselves to value autonomy and independence, gravitating toward smaller businesses and more flexible employment arrangements. No surprise, then, that according to startup tracker Crunchbase, the average startup in a supply chain today is smaller by almost a third than those that participated in the decade 2000–2010.10 Indeed, some suppliers are so tiny that their connections with large firms can appear more like talent sourcing than procurement.

For the most part, supply chain functions of large businesses weren’t set up to deal with a world of thousands of partners. Now they must adjust.

For many corporations, these connections can bring many advantages, but also invite greater complexity. For the most part, supply chain functions of large businesses weren’t set up to deal with a world of thousands of partners. Now they must adjust. So, for example, we see firms establishing or relying on new “platforms” to facilitate greater levels of connectivity, collaboration, and co-creation with other businesses. (As a familiar example of a platform, picture Amazon Services, which provides its customers with an e-commerce infrastructure for order-taking and fulfillment, allowing them to focus on their offerings.)

In China, Alibaba allows small businesses to build their own supply chains, acting as a facilitator of relationships between firms that otherwise would not or could not cooperate. In the United States, IBM launched Supplier Connection, a platform-based network that helps large firms manage their connections with smaller businesses.11 Across many industries we see the rise of “value networks” that use cloud computing and social network platforms to enable many-to-many supplier connections. For example, Real Time Value Network has over 30,000 trading partners, allowing supply chain managers to more easily find the small players that can bring ideas and flexibility to their arrangements.12

New software tools can also provide broader perspective and deeper insight into expanding value webs. Amgen, for example, which offers treatment for serious illnesses such as cancer and kidney disease, has seen its network expand substantially. “Originally most of our suppliers were closer to home,” observes executive director of supply chain Patricia Turney. “More and more, we’re finding that we are sourcing materials from really remote locations.” So Turney has put tools in place to map the whole ecosystem, and a process to create a “war room” when disruptions threaten supply lines. A few months into implementation, she reports, “We already have some new insights into our tier 2 suppliers and where they’re located that we didn’t have before.”13

Reducing risk, raising resilience, deploying data

Patricia Turney’s comments also serve to highlight the ways in which risk can be reduced in increasingly complex value webs. It seems to be working well for Amgen: As Turney also observed, “We have a phrase . . . ‘every patient, every time.’ We’ve never shorted the market, never had a patient go without life-saving medicine. . . . [We have] 24/7 oversight.”14

Since their inception, supply chains have generally been tightly associated with risk management and business continuity planning. Globally extended production and distribution arrangements are often subject to risk factors beyond anyone’s control—from geo-political events to natural disasters. Dependency on the capabilities and integrity of others outside your organization, even if tightly contractually controlled, can create certain vulnerabilities. And, if it was ever possible to lay the blame for product deficiencies on suppliers, that is not likely to remain a credible excuse. For example, in 2013, millions of food products advertised as containing beef were withdrawn from shelves in Europe after they were found to contain horsemeat. The scandal highlighted deficiencies in the traceability of the food supply network, and dealt a blow to the finances and reputations of affected brands, retailers, and restaurants.15 It is simply expected today that firms have clear visibility into the activities—and the integrity—of their vendors.

Increasingly complex, highly distributed networks can generate some new risks, but there is a paradox here. Many also have high levels of resilience and can be, in writer Nassim Taleb’s phrase, “anti-fragile”—displaying self-organizing, flexible qualities surprisingly capable of reconfiguring to overcome shocks and disruptions.16 These qualities are usually stronger when underpinned by strong, enduring relationships. Consider the experience of Renesas, a Japanese producer of microcontrollers, when the 2011 earthquake severely damaged its main production facility. After a swarm of workers from its suppliers and customers voluntarily showed up in sub-zero temperatures and got the plant up and running again, their value web was in many respects stronger for the experience.17

Designing resilience into supply chains and value webs will likely rise in importance, and be supported by new capabilities. For example, 3D printing technologies already enable some supply chains to reduce dependency on far-flung production arrangements. When British fighter jets flew for the first time with components made using 3D printing technology in early 2014, Mike Murray, head of airframe integration at BAE Systems, described a new-found freedom afforded by the technology. “You are suddenly not fixed in terms of where you have to manufacture these things,” said Murray. “You can manufacture the products at whatever base you want, providing you can get a machine there.”18Data is also likely to play an increasingly critical role, especially as the Internet of Things enables vast amounts to be collected and analyzed to create greater transparency and discover opportunities, efficiencies, and problems. However, in Deloitte’s 2015 supply chain survey, only 46 percent of respondents rated their analytics competencies as currently very good, while 67 percent expected them to become more important in the next five years.

Attracting and developing next-generation talent

Talent considerations are also on the rise. Value webs can be an increasingly important source of hard-to-access talent, especially as new and more open models proliferate. Development of the talent of partners is also rising in importance for many firms such as Nike, which are placing increased emphasis on providing shared training programs for suppliers’ employees.19

The supply chain profession itself is also clearly evolving, and will require important new skills and capabilities: design of resilient networks; management of reciprocity-based relationships; adoption of technologies such as 3D printing; and analytics. No wonder the US Bureau of Labor Statistics has calculated that the number of logistics-related jobs will increase by 22 percent between 2012 and 2022.20

Recruiting for these positions may need to be creative. In Deloitte’s 2015 supply chain survey, 70 percent of top-performing supply chain functions expect to use non-traditional recruitment methods in the coming years. In their training efforts, too, they will benefit from preparing veteran managers for deeper collaboration with other business functions and leadership and more central participation in the evolution of strategy.

The most effective supply chain leadership is already at a premium. In the Deloitte 2015 supply chain survey, 71 percent of executives claimed that it was difficult to recruit senior supply chain leaders,21 and only 43 percent felt that their supply chain strategic thinking and problem solving was very good. With 74 percent surveyed also saying that such strategic thinking and problem solving will increase in importance, it seems there is no time to lose (see figure 3).

What’s next?

As the business landscape increasingly configures around dynamic, highly interactive ecosystems, supply chains will likely evolve substantially. Many larger firms will invest in their own supplier ecosystems, recognizing that feeding and nurturing them will help generate demand, innovation, and support in a variety of ways that cannot always be predicted. New mindsets are likely to take hold as the profession embraces more networked and “web-like” arrangements. New leadership capabilities will be increasingly valued, as relationships based on reciprocity, mutual trust, and shared interests become increasingly vital and effective. Listen, for example to Kurt James, a supply chain leader at McDonald’s supply chain:

When hiring, we look for people with character traits uniquely suited to our supply chain—namely, an innate sense of fairness and an ability to consistently empathize with the challenges suppliers face in meeting our often aggressive deadlines, standards, and evolving needs.22

New mindsets are likely to take hold as the profession embraces more networked and “web-like” arrangements.

Substantial experimentation will likely occur, driven particularly by the increasing prevalence and predictive qualities of data. In the realm of social data, for example, “Nowcasting” is a growing field of social listening-enabled forecasting. A recent study analyzed Twitter posts to estimate influenza infection in New York City and proved far more accurate than traditional seasonal flu trend estimates.23 When real-time data sources from across massive webs are brought together, new insights can emerge that enable, for example, far more accurate and localized demand forecasting. New value webs will form as 3D printing transforms multiple aspects of today’s global supply chains, enabling operations to atomize in ways few can even imagine today. Amazon, for example, filed for patents in February 2015 for installing printers in delivery trucks—taking the concept of “real-time” to a new level.24

Many supply chain professionals will become more closely connected to colleagues who are creating “on-demand” talent models, or designing new, more open innovation systems. Consider major corporations such as Ford, AutoDesk, Intel, and Fujitsu that have forged partnerships with TechShop, a growing chain of “makerspaces,” enabling them to connect with the fast-growing Maker Movement.25

All this will compel the supply chain profession that helped shape today’s economy to adapt in turn to its new demands. As ecosystems become increasingly central to business strategy, the core value of the profession will lie less and less in getting the same things done ever more efficiently, and more and more in the strategic pursuit of creating new value, achieving breakthrough performance, sustaining growth, and—once again—changing the world.

My take

By Frank Crespo

Frank Crespo is vice president and chief procurement officer for Caterpillar Inc., where he leads the company’s procurement and logistics functions for products, parts, and services delivered across the $55 billion business.

As supply networks have gone global, complex organizations like Caterpillar find themselves coordinating the activities of thousands of suppliers, globally scattered, each with its own operating subtleties. By volume and variety, we have one of the largest, most complex supply networks in the world, with two-thirds of our suppliers tapped into complex chains of their own. That’s why we made the conscious effort to stop referring to our supply network as a supply “chain.” More than a name change, for us it was about getting our teams and suppliers to realize that everything has interdependencies. To be world class, especially with the ever-increasing clock speed of business, there must be synchronization.

As supply networks have gone global, complex organizations like Caterpillar find themselves coordinating the activities of thousands of suppliers, globally scattered, each with its own operating subtleties. By volume and variety, we have one of the largest, most complex supply networks in the world, with two-thirds of our suppliers tapped into complex chains of their own. That’s why we made the conscious effort to stop referring to our supply network as a supply “chain.” More than a name change, for us it was about getting our teams and suppliers to realize that everything has interdependencies. To be world class, especially with the ever-increasing clock speed of business, there must be synchronization.

The complexity and lack of linearity in a global supply network makes it essential to understand the signals and flows between network nodes. The flow of information is just as important and potentially disruptive as the physical flow of materials. But seeing the data is just the first step. We must also understand what the facts mean and be able to quickly make the right business decisions based on those facts. Failure to do so can lead to actions based on assumptions, which then creates a firefighting mentality versus a proactive, preventive environment.

What Caterpillar is really driving toward is a lean, responsive, and resilient global supply network. While the work of getting there is never fully finished, our suppliers are not alone on that journey. Caterpillar places a great emphasis on collaboration across the network and we can point to the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan for evidence of our shared progress. Many organizations took more than four months to recover from the disruptions. Caterpillar’s supply network took fewer than 45 days.

To make it all work seamlessly, you must have complete buy-in. We spend a great deal of time internally reinforcing our vision at Caterpillar. We also spent a good portion of last year meeting with hundreds of suppliers around the world communicating that vision. One of the first things I told my team the day I arrived at Caterpillar is that it’s all about visibility. No matter how good your talent is, without all stakeholders seeing and hearing the same things, you’re not going to make the best decisions—whether about resources, prioritizations, or trade-offs.

The globalization of business brings a level of complexity that leaders today have likely never experienced. The way we tackle it, though, is simple. Start with the facts. Know what’s going on in your facilities and what’s flowing between them. Organize the supply network well, clarify the definitions of success, facilitate the movement of information, and a healthy supply network will follow. We have to know how to lead and coordinate a vast and decentralized web of interconnected suppliers, or risk being hostage to it.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.