The gig economy has been saved

The gig economy Distraction or disruption?

Jeff Schwartz United States

Jeff Schwartz United States Dr. Udo Bohdal-Spiegelhoff Germany

Dr. Udo Bohdal-Spiegelhoff Germany Michael Gretczko United States

Michael Gretczko United States Nathan Sloan United States

Nathan Sloan United States

How can a business manage talent effectively when many, or even most, of its people are not actually its employees? Networks of people who work without any formal employment agreement—as well as the growing use of machines as talent—are reshaping the talent management equation.

View the complete Global Human Capital Trends 2016 report

Explore

View 2016 Global Human Capital Trends

Create and download a custom PDF

Watch the related video

Explore the related infographic

From the increasing use of contingent freelance workers to the growing role of robotics and smart machines, the corporate workforce is changing—radically and rapidly. These changes are no longer simply a distraction; they are now actively disrupting labor markets and the economy.

- Almost half of the executives surveyed (42 percent) expect to increase or significantly increase the use of contingent workers in the next three to five years; 43 percent anticipate greater deployment of robotics and cognitive technologies. Three out of four executives (76 percent) surveyed expect automation will require new skills in the workforce in the next one to three years.

- The concept of “contingent workforce management” is being reshaped by the “gig economy”—networks of people who make a living working without any formal employment agreement—as well as by the increased use of machines as talent.

- New regulations that mandate pay for overtime, increase the minimum wage, and tighten rules for part-time status are becoming more important than ever, with a growing public policy debate over how to regulate and measure new labor models.1

Three years ago, Deloitte introduced the concept of the open talent economy, predicting that new labor models—on and off the balance sheet—would become increasingly important sources of talent.2 Today, they are.

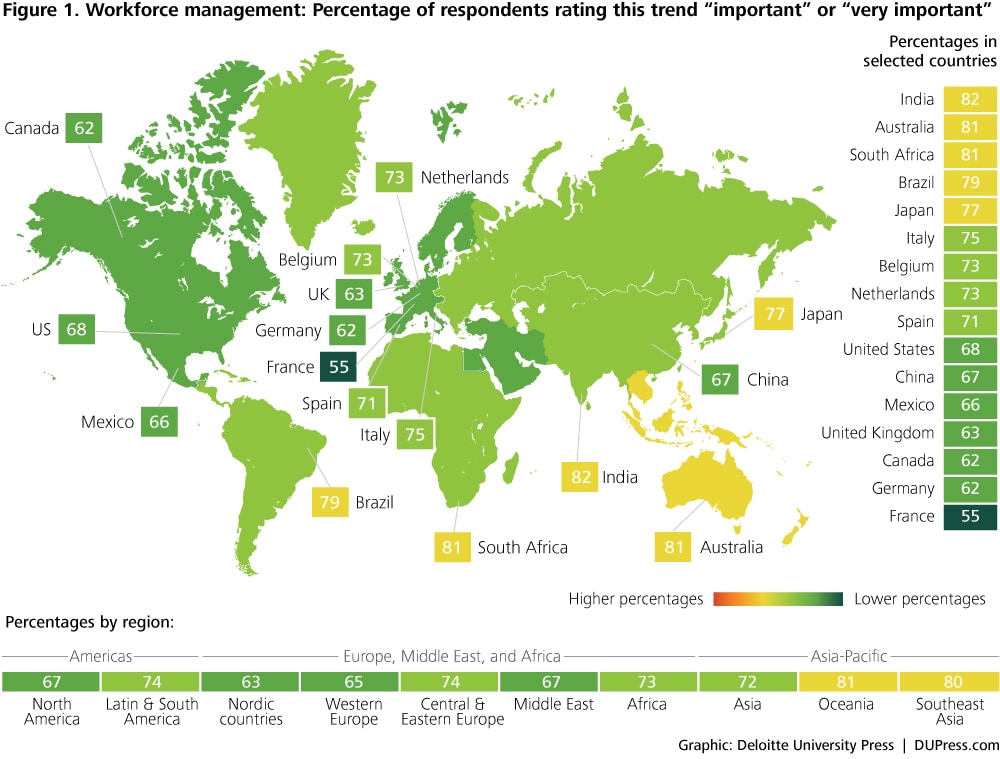

Granted, respondents to this year’s survey rated workforce management the least important of the trends we explored. (See figure 1 for our survey respondents’ ratings of workforce management’s importance across global regions and selected countries.) Nonetheless, rapid changes in the nature of the workforce, through new labor markets and models and through automation, present important challenges for business and HR leaders.

At an even more basic level, companies are struggling to understand who (and what) their workforces are composed of and how to manage today’s incredibly diverse combination of worker types.

Today, more than one in three US workers are freelancers—a figure expected to grow to 40 percent by 2020.3 This year’s survey confirms that the contingent workforce has gone global. Fully 51 percent of executives in our global survey plan to increase or significantly increase the use of contingent workers in the next three to five years, while only 16 percent expect a decrease.

Companies such as Airbnb and Uber embody this trend, but they are not the only organizations profiting from the “gig economy.” Companies in all sectors—from transportation to business services—are tapping into freelance workers as a regular, manageable part of their workforces. Cost structure is one factor driving this trend, with some companies opting to pay purchase orders instead of salaries. The availability of talent is another factor; data scientists, for example, may not be willing to move to a company’s remote headquarters but could be engaged remotely and temporarily.

In addition to broader economic and social changes driven by the gig economy, new labor models are expanding beyond contingent workers to include the rapidly growing integration of robotics and cognitive technologies into the workforce. These automated “employees” represent a new form of talent that HR must be prepared to engage and manage.

Within the next three years, 42 percent of executives surveyed expect to increase the use of robotics and cognitive technologies. But, contrary to some news headlines, most organizations do not expect workers to be replaced by machines. In fact, 20 percent expect automation to increase hiring levels, while 38 percent see no impact.

At an even more basic level, companies are struggling to understand who (and what) their workforces are composed of and how to manage today’s incredibly diverse combination of worker types, including workers on and off the balance sheet as well as part-time, contingent, and virtual workers. Across all organizations, industries, and geographies, a new work and social contract is emerging. Today’s HR organization needs to adapt to these changes in the 21st-century workforce.

These new additions to the workforce, after all, work side-by-side with those on the balance sheet. Many have been recruited through the procurement office rather than HR systems. But all affect the company’s reputation and brand. How can HR manage and motivate all these types of workers?

Many HR teams struggle to understand the forces shaping today’s workforce, particularly when translating these new realities into attractive and cost-effective workforce practices that comply with government regulations. According to this year’s survey, 71 percent of executives believe their companies are “somewhat” or “very” able to manage contingent workers. The top three challenges cited include legal or regulatory uncertainty (20 percent), a corporate culture unreceptive to part-time and contingent staff (18 percent), and a lack of understanding among leadership (18 percent).

The move toward automation, robotics, and cognitive technology in the workforce also poses significant challenges. Three out of four executives in this year’s survey believe automation will require new skills over the next several years. When asked about their organization’s capabilities to redesign work done by computers to complement talent, only 13 percent of executives rated them “excellent”—34 percent (1 out of 3) described them as “weak.”

Consider some of the challenges: One major telecom company measures its workforce as either 18,000 (payroll), 30,000 (including contractual workers), or 57,000 (including those who are building out its network)—a huge variance, depending on how the workforce is measured. Uber has three million drivers under contracts that offer the company tremendous flexibility. Are they part of its workforce? And who will decide that question—regulators or the business itself? Could benefits for these workers be allocated through micropayments, for instance?

These questions present a number of challenges. HR can modify policies and programs, but when even a figure as simple as the number of workers at an organization is open to so much interpretation, HR’s task becomes highly complex.

In short, leading organizations are exploring how to make real the promise of the open talent economy. Fundamental questions confront business and HR leaders:

- Who, where, and what is the workforce?

- How can HR, procurement, and IT collaborate to plan and manage the 21st-century workforce?

- How can the best workers be attracted, acquired, and engaged for an optimal cost, no matter what type of work contract they have?

- How can companies leverage automation and smart technologies to improve productivity and create more meaningful and engaging work where employees “race with—not against—machines”?4

There is no simple formula to help companies figure out the optimal mix of talent, skills, and type of worker. Resolving this challenge remains a dream for the future, but that does not relieve organizations of the responsibility to understand and take control of this trend.

One approach is to address whether there are ways in which a blended workforce may be managed more consistently in the organization. Perhaps this push itself will help organizations begin to understand and measure their total workforce and labor costs, rather than simply abandoning the task as HR focuses only on the full-time workforce. And how many people with responsibilities for talent acquisition are proactively working with the CIO to ask if there are machines that can perform jobs?

Today’s disparate time collection, labor procurement, scheduling systems, and contingent workforce management solutions do not provide the necessary insights. Disjointed and owned by separate business functions, these systems are tough to align with the new programs needed for the new workforce. Many of today’s applicant-tracking systems are in some ways merely automated filing cabinets. Without these insights, though, no one is truly managing the workforce.

Companies face a new and far more subtle competition for talent, especially as unemployment falls in some markets and voluntary turnover rises.5 Organizations will need new technologies, new ways of measuring costs, and even a new language of talent management for the 21st century.

Lessons from the front lines

The gig economy poses significant questions and opportunities for companies and their workforce talent strategies.

First, in a growing number of industries, technology-enabled talent markets—operating through platforms—are offering new sources of competition. Consider Uber and Lyft for transportation-for-hire services, Topcoder for programming, Handy for household repair projects, Tongal for ads and videos, Hourlynerd for consulting projects, and many others. Companies need to assess how to compete with firms that use talent platforms as their primary means of organizing their workforce.

Second, and perhaps more important: How can companies utilize and leverage gig economy markets to complement their talent and workforce strategies?

One example is how companies are leveraging their creative teams and traditional agencies with new, on-demand models. Tongal advertises itself as “the world’s first studio on demand,” and provides online markets and contests to connect businesses with creative talent around the world to produce ads, videos, music videos, and other products.6 Tongal’s corporate clients include some of the largest companies in the world: Johnson and Johnson, Dannon, LEGO, Ford, and Lenovo.7

To integrate models like Tongal will likely require procurement, business, and HR managers to work together to access and coordinate new models—like on-demand talent markets and crowdsourced competitions—with more traditional in-house teams and outside advertising and creative agencies.

A second example comes from Thomson Reuters, the global information services company. With 55,000 employees and 17,000 technologists, the company launched a crowdsourcing model inside the company. The program posed technology challenges to the company’s engineers to solve problems in other Thomson Reuters divisions—breaking down internal silos and leveraging the insights of the company’s own internal network.8

Where companies can start

- Take a new view of 21st-century talent: Organizations must understand the open talent economy and their needs for different types of workers and automation over the medium term (3 to 5 years) and longer term (5 to 10 years). The process starts with an expansive workforce plan that proactively incorporates on- and off-balance sheet talent, as well as combinations of robotics, thinking machines, and new labor/technology collaborations.

- Designate a “white space” leadership team for workforce and automation planning: Workforce planning for the new workforce is a “white space” exercise. Corporate technology, procurement, and business strategy teams should join HR to produce robust plans for different types of labor and technology combinations.

- Focus on acquisition—both of people and machines: Once companies have a sense of the specific outlines of their talent needs, they can focus on acquiring and engaging each segment of employees with the overall plan in mind. Sources of talent should include people that companies recruit and engage in different ways. Technologies and machines can be used to complement employees on corporate payrolls.

- Broaden and sharpen the focus on productivity: Productivity, and its flip side, engagement, are being reimagined by new workforce and automation opportunities. These new workforce models and new combinations of talent and technology are critical for improving corporate productivity. New workforce planning approaches integrating multiple workforce segments, automation, and cognitive technologies will enhance productivity and product and service quality.

- Develop new workforce and automation models that focus on engagement and the skills of your critical workforce: Increasing employee engagement is one of today’s most important workforce challenges. Companies today must learn how to use new workforce segments and technologies to improve the quality, meaning, and value of the work of their employees.

Bottom line

The design of the 21st-century workforce will present new challenges to HR, technology, and business leaders that require deeper levels of collaboration to develop solutions. The open talent economy and the new workforce-machine age are coming into focus, redefining “talent” to include people and machines working in different places under different contracts.9

This is not simply a distraction; it’s the beginning of a 21st-century workforce transformation. Leading companies are tackling the questions that need to be answered to compete successfully for talent in this new environment. Who and what will the workforce be composed of? How will it be acquired? How can its productivity be measured? How can the organization optimize the new mix of workers from different sources? Given that many segments of a workforce have an impact on products and customers, what are the appropriate ways to engage all of those segments? And who will lead these efforts?

Deloitte’s Human Capital professionals leverage research, analytics, and industry insights to help design and execute the HR, talent, leadership, organization, and change programs that enable business performance through people performance. Visit the “Human Capital” area of www.deloitte.com to learn more.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.