Master protocols Shifting the drug development paradigm

17 September 2018

Master protocols, a collaborative approach to drug development, could help biopharma companies derisk research programs, improve the quality of evidence, and enhance R&D productivity by cutting down research cost and time.

Executive summary

Master protocols could help address scientific, operational, and competitive challenges in the existing drug development model. These adaptive, collaborative clinical studies allow for the simultaneous evaluation of more than one drug for individuals with specific diseases or disease subtypes within the same structure.

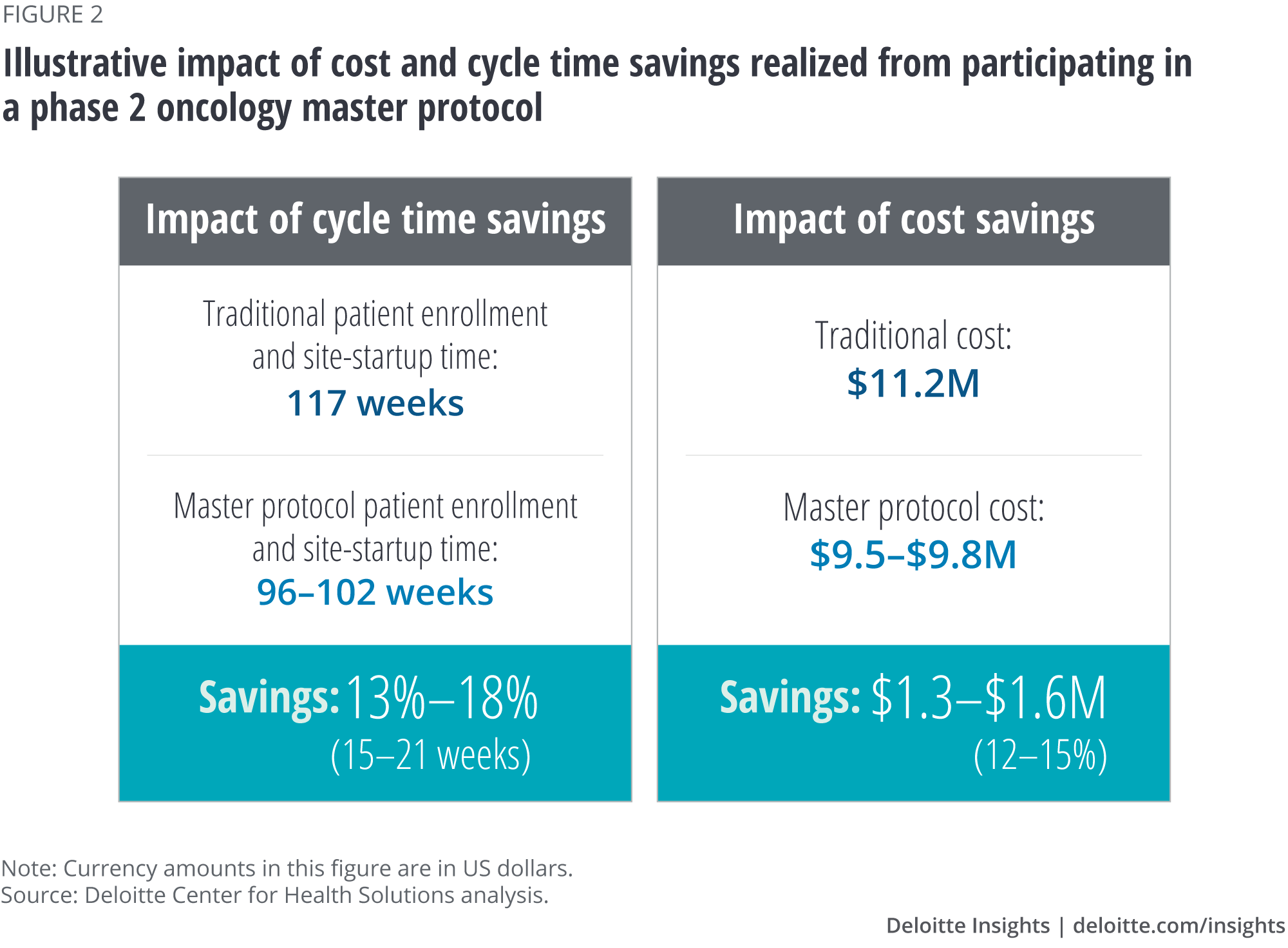

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions (DCHS) interviewed 12 individuals who participate in master protocols from academia, nonprofits, and biopharma to better understand the benefits and tradeoffs for pharma companies participating in master protocols. Our analysis confirms that biopharma companies can derisk research and development (R&D) programs, improve the quality of evidence, and enhance R&D productivity by participating in master protocols. In fact, the potential cost and cycle time impact on a phase 2 oncology trial could be:

- Cost reduction of 12–15 percent (from about US$11 million to about US$9.5 million); and

- Study time reduction of 13–18 percent (about 15–21 weeks), helping accelerate successful products to market.

Understanding master protocols: A collaborative approach to R&D

Biopharma companies are facing an increasing number of challenges in drug development. Over time, developing new drugs has become complex, risky, and expensive. Specifically, the current model—testing one drug, on one target at a time, in one trial—often results in a long, sequential cycle of drug development, millions of dollars in sunk costs, and delays in getting the most effective treatments to patients. This can be especially true in disease areas like immuno-oncology, where the science is complex, the unmet need is high, and pipelines are crowded. In these areas, where biopharma companies sponsor a multitude of individual, sequential trials, competing trials could make the recruitment of patients difficult. Patients, too, struggle to navigate the complex trial landscape to find the optimum trial.

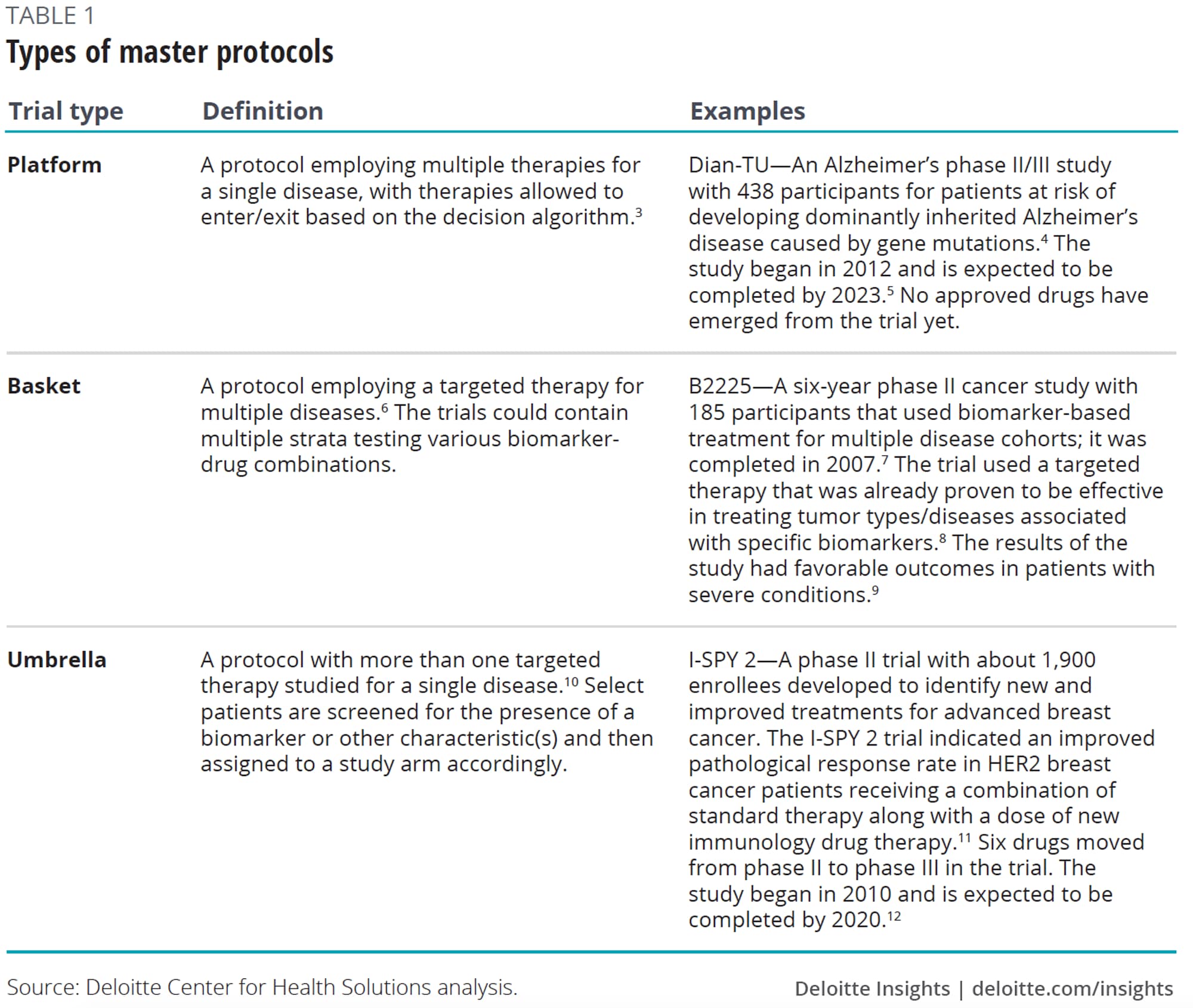

Master protocols could help alleviate some of these challenges. These adaptive, collaborative clinical studies that allow for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple treatments for individuals with specific diseases or disease subtypes within the same trial structure,1 are devised to efficiently answer multiple questions in less time.2 Common types of master protocols are platform, basket, and umbrella trials (see table 1).

Master protocols could reduce the need for redundant clinical trials, enable multiple companies to share infrastructure (including analytical capabilities and costs), and test clinical hypotheses in parallel. They tend to be suited for complex or rare disease areas and can either expedite drugs to market or the decision to terminate unsuccessful programs. Master protocols can offer a patient-centric approach by screening patients just once and enrolling them in an optimum treatment arm.

Master protocols have historically been driven by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), nonprofits, and academics. In fact, the NIH helped lay the foundation for innovative master protocols in the early 1990s. For example, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsored the Asthma Clinical Research network, which used a centralized governance and infrastructure to follow the master protocol approach. Similar models took on schizophrenia as part of Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE).13

Private sector models have since emerged. An example, the I-SPY trial, originated in 1998 when two physician researchers at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) who saw the need for a more precision-medicine approach to breast cancer (see table 1 for more details on I-SPY 2, currently ongoing).14 I-SPY established the master investigational new drug application (IND), allowing for new drugs to easily enter an established master protocol. Building off these learnings, in 2014, the nonprofit group Friends of Cancer Research launched the LungMAP trial which is testing targeted therapies in advanced forms of lung cancer. Friends of Cancer Research worked in collaboration with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and industry partners to develop the clinical trial design.15

Master protocols are typically suited to complex and rare diseases

Master protocols may not be appropriate for all types of compounds or disease areas. They are most likely to be of value in complex and rare diseases, where the benefits of bringing stakeholders together to understand the biology of the disease outweigh the challenges of putting together the effort. To date, these trials have been popular in oncology, with a focus on evaluating genetic subtypes of diseases. Examples include I-SPY 1 and 2, BATTLE, and LungMAP.

Next to oncology, trials have focused on the conditions of the central nervous system (CNS), primarily Alzheimer’s disease. But adoption has been more limited in the CNS because the genetic understanding is often not as advanced as in certain oncology areas. However, collaborators can come together to help identify and validate biomarkers for this poorly understood disease, especially for subpopulations.

Beyond oncology and CNS, master protocols can be of value in disease areas where the science is not well understood, where researchers need to identify and target therapies to subpopulations, or for rare diseases where patients are difficult to recruit.

Understanding the benefits and tradeoffs of master protocols for biopharma companies

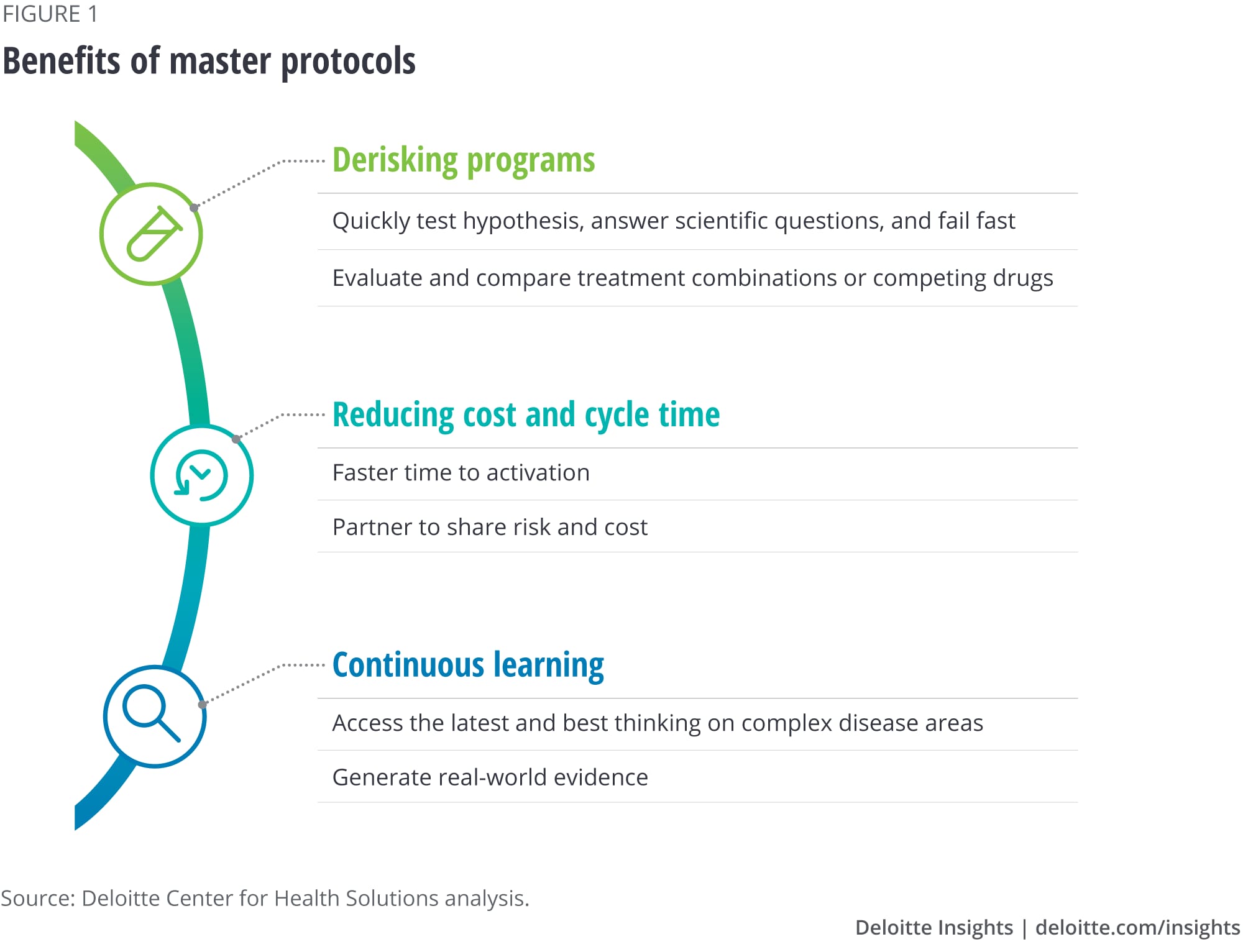

Our research shows that master protocols bring multiple benefits to drug manufacturers (see figure 1).

- Ability to quickly test hypotheses, answer scientific questions, and fail fast. Master protocols can allow pharma companies to test a hypothesis, particularly in disease areas with high unmet needs, where finding the right patient subpopulation or validating a biomarker is challenging.

- Evaluation and comparison of treatment combinations or competing drugs. Traditional clinical structures test one combination at a time, which may not always be the best way to assess what combinations work best for patients. Master protocols allow researchers to experiment with a variety of drug combinations, which can help companies better predict which combinations may fail faster than through traditional trials.

- Faster time to activation. Master protocols can offer biopharma companies the flexibility to plug into existing well-established infrastructure and patient cohorts. With this ready infrastructure, stakeholders can gain efficiency in cycle times. Adaptive settings can also allow for interim monitoring of success or failure.

- Risk- and cost-sharing. The different stakeholders involved in collaborative trials share the costs related to these trials. Master protocols with multiple arms can thus enable more efficient and cost-effective trials.

- Access to the latest and best thinking for complex disease areas. Master protocols are increasingly employed for complex diseases, such as cancer and Alzheimer’s, and other rare indications. Successful collaborative groups that initiate these trials typically seek to bring together the leading research and clinical experts together to establish these protocols.

- Generation of real-world evidence. The long-term observational data that the trials create can act as a continuous learning system. Potential benefits include generating evidence that a select therapy is as effective as or more effective than others being developed, and supporting the value proposition of a therapy, which can be helpful in reimbursement discussions.

Potential cost and cycle time savings from collaborative trials

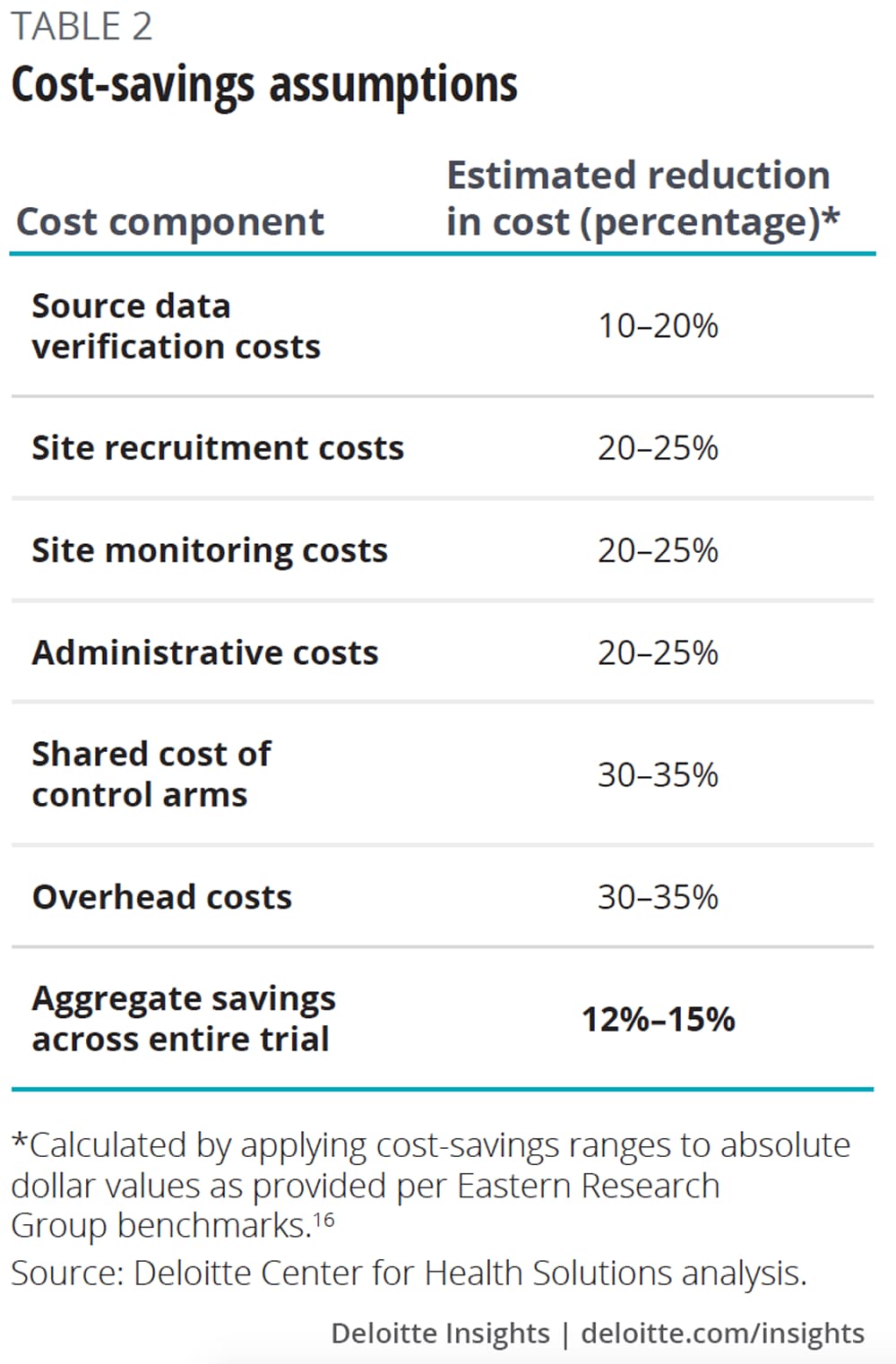

To estimate the potential cost and cycle time savings companies might realize from participating in master protocols (table 2), we put forward a scenario to our interviewees, asking them for their input on potential savings. We then applied these estimates from interviewees to industry benchmarks for the expected cost and cycle time of a phase 2 oncology clinical trial.

Our analysis suggests that companies can potentially save 12–15 percent of the cost (US$1.3M–1.6M) and 13–18 percent of study duration (15–21 weeks) by participating in a phase 2 oncology master protocol (figure 2).

Our research suggests that master protocols could reduce the following typical trial costs by reducing redundancies and leveraging shared infrastructure, including:

- Startup and site recruitment;

- Site monitoring and site data verification;

- Infrastructure, overhead, and administrative costs; and

- Control arms.

Estimate of shorter cycle time from collaborative clinical trials

Based on industry benchmarks and our interviews, we estimated how master protocols could shorten cycle time for a phase 2 oncology trial. Interviewees told us that the primary source of cycle time savings are faster site initiation and patient recruitment.

Based on our calculations, a 10–15 percent reduction in patient recruitment time (First Subject Initiated to Last Subject Randomized) and a 25–30 percent reduction in site startup time (First Protocol Approved to First Subject Initiated) would result in an aggregate cycle time savings of 13–18 percent, or 15–21 weeks (table 4).17 This cycle time reduction could help lower trial costs and bring the drug to market faster.

A major benefit of master protocols is the potential to answer scientific questions faster, which could result in significant time savings. Instead of pursuing a one-drug, one-purpose approach, master protocols could allow for the seamless adaptation and testing of drugs for multiple purposes, patient populations, or in combination. Answering scientific questions more quickly could enable companies to terminate unsuccessful programs or advance promising therapies to market. We have not tried to estimate this cycle time benefit but it is likely to be much more significant than the aspects we did model.

The cost impact of terminating programs earlier, reducing the cost of failure, could also be significant. Further, the revenue impact of accelerating products to market with differentiated value propositions could add to the business case for pursuing a master protocol approach, beyond the cycle time and cost impacts described here.

What should companies consider when deciding to participate in master protocols?

Master protocols can bring multiple benefits, but many biopharma companies are just beginning to explore these models. While some interviewees were hesitant about working in a new, collaborative environment with a nontraditional regulatory pathway, biopharma companies can identify and mitigate potential risks early by considering the following factors:

- Governance model. Participating companies should be mindful of the level of control they will be given in the trial setup. Typically, the collaborative is responsible for the study design, and while pharma companies can provide input, academics and investigators usually make the final call. Pharma companies should consider whether or not they will have voting rights around key elements of study design. It is also critical to clarify what elements of IP coming out of the trial will be owned by the pharma company versus the collaborative.

- Stakeholder incentives. While academics and biopharma companies can both benefit from participating in master protocols, they can be motivated by different objectives. For example, academics are often looking to advance science and publish findings. Biopharma companies are typically motivated to get drugs through the highly regulated drug development process as quickly as possible. If academic investigators do not share this same sense of urgency, it could lead to program delays. Success or failure of the trial often depends on the collaborating partners. This makes it imperative for stakeholders funding the trial to define the expected contributions from each partner.

- Operational factors. It is critical to understand the time it might take to set up the master protocol and to establish an investigator network. Companies that are already well established in the disease area in question might be able to tap into existing investigator networks and set up a trial faster. Companies should also consider the stage of development of the compound and whether the master protocol is registration grade (meets regulatory standards for inclusion in a new drug application).

- Regulatory factors. Many companies have expressed concerns about diverging from traditional regulatory pathways, but regulators have signaled strong support for these trials (see sidebar) and the FDA is welcoming dialogue with companies that want to pursue these models. Companies should involve regulatory agencies early so that they can review the master protocol or the trial design up front and avoid bottlenecks at a later stage when cohorts or treatments are being modified in late phases of the trial.18

- Scientific. It is important to consider how the evidence is being recorded, managed, and analyzed. The statistical approach should ideally be in line with the latest approaches and data science. In addition, it’s important to ensure that the latest standard of care is being employed in the trial.

The FDA is supporting master protocols

Scott Gottlieb, MD, the commissioner of the FDA, has spoken about master protocols as one way to address the high and rising expense of developing a new drug. Gottlieb sees advancing the use of master protocols as a strategy to enable more coordination within the same trial structure to evaluate treatments in more than one subtype of a disease or type of patient.19 In an editorial coauthored for the New England Journal of Medicine in July 2017, Janet Woodcock and Lisa LaVange of the FDA stated that as the targets for new drugs become more precise, coordinated research efforts such as master protocols are the way forward.20

The biopharma industry relies on the FDA’s robust and continually adaptive regulatory and guidance process. Many of our interviewees said that the FDA has struck the right balance in moving forward novel types of trials such as master protocols by providing the appropriate level of guidance at the right time. Companies that want to move forward with master protocols should consider early dialogue with the FDA and other regulatory agencies to discuss how best to support study objectives.

Implications for stakeholders

Given the need to make the drug development process more patient-centric and reduce the cost and complexity of drug development, stakeholders should continue to work through the challenges and pursue innovative collaborative trials. Because there are multiple stakeholders participating in these trials, collaborative groups should consider how to strike the right balance in research priorities and incentives for all the participating entities.

We found that nonprofits and patient advocacy groups are likely best positioned to create these collaborative groups; however, they have the fewest resources. These groups often approach the trials by gathering all the existing knowledge on a disease area and involving the right stakeholders in the study. Working on behalf of patients, they are often motivated to collect and share information.

Biopharma companies, with much deeper R&D budgets, should strongly consider contributing to these important initiatives, and they should be given the appropriate level of influence over study design. While companies may need to explore new territory, our scenario analysis suggests it could be the right time to consider collaborative approaches. Collaborating could result in not only significant synergies and savings for the industry, but could also advance promising personalized therapies to market.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.