GovCloud: The future of government work has been saved

GovCloud: The future of government work

01 January 2012

- Charlie Tierney, Steve Cottle, Katie Jorgensen

Rather than existing in any single agency, GovCloud workers could reside in the cloud, making them truly government-wide employees.

Introduction

Wind back the clock to 1971. Jane, a freshly minted college graduate, joins the government as a clerk. Jane’s work consists largely of entering information into databases and creating reports, which requires her to spend the better part of her work day seated at a terminal near a mainframe computer that fills an entire room. Jane and her colleagues are expected to be at their desks from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., five days a week. Jane is grateful to have a steady 9-to-5 job, and plans to spend her entire career with her agency.

Flash forward 40 years and meet Jane’s grandson, Ian. He carries a slim tablet wherever he goes, which has more computing power than the mainframe with which Jane worked. Ian is constantly tethered to the Internet and works 24/7, from wherever he is. Ian expects to switch from project to project and office to office as his career develops and his interests evolve. If he feels he has reached the limit of his ability to learn or grow in one role, he will look elsewhere for a new opportunity. What if the government could give Ian the opportunities and experiences he seeks?

The GovCloud concept proposed in this paper would restructure government workforces in a way that takes advantage of the talents and preferences of workers like Ian, who are entering the workforce today. The model is based on a large body of research, from interviews with public and private sector experts to best practices from innovative organizations both public and private.

“This is the first generation of people that work, play, think, and learn differently than their parents... They are the first generation to not be afraid of technology. It’s like the air to them.” — Don Tapscott, author of

This report details trends in work and technology that offer significant opportunities for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the government workforce. It lays out the GovCloud model, explaining how governments could be organized to take advantage of its flexibility. It examines how work would be performed in the new model and discusses potential changes to government HR programs to support GovCloud. Other sections provide resources for executives, including a tool to help determine cloud eligibility, steps they can take to pilot the cloud concept, and future scenarios illustrating the cloud in action.

The GovCloud model represents a dramatic departure from the status quo. It is bound to be greeted with some skepticism. Without such innovation, however, governments will be left to confront the challenges of tomorrow with the workforce structure of yesterday. The details of the GovCloud model are open for debate. The purpose of this paper is to jumpstart that debate.

How we work today—and tomorrow

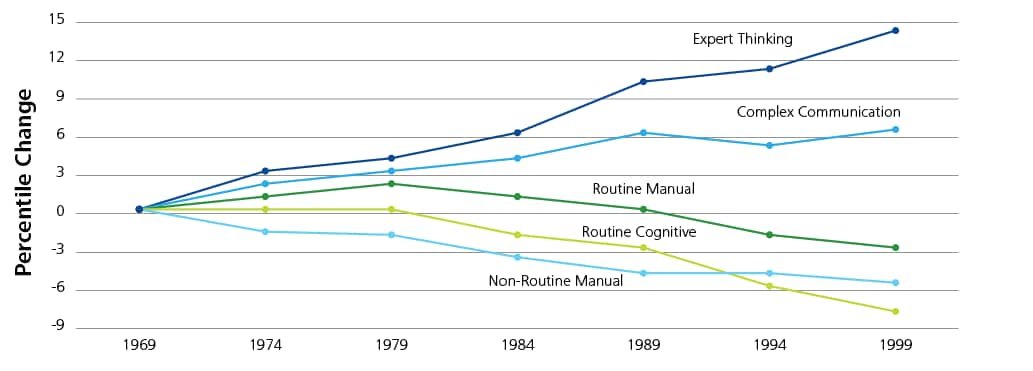

Forty years ago, more than half of employed American adults worked in either blue-collar or clerical jobs. Today, less than 40 percent work in these same categories, and the share continues to shrink.1 Jobs requiring routine or manual tasks are disappearing, while those requiring complex communication skills and expert thinking are becoming the norm.2 Increasingly, employers seek workers capable of creative and knowledge-based work.

“We should ask ourselves whether we’re truly satisfied with the status quo. Are our workday lives so fulfilling, and our organizations so boundlessly capable, that it’s now pointless to long for something better?” — Gary Hamel, author of The Future of Management

The next generation of creative knowledge workers has already entered the job market. These “Millennials” came of age in a rapidly and radically changing world. They are the first true digital “natives.” They have grown up with instant access to information through technology. As such, Millennials have considerably different expectations for the kind of work they do and the information they use. The pursuit for variety in work has led Millennials to cite simply “needing a change” as their top reason for switching jobs.3

Advances in technology have also changed the actual ways in which people perform work. The ability to crowdsource tasks is one example of this change. Since its founding in 2001, volunteers have produced and contributed to over 19 million articles in 281 languages on Wikipedia.4 Built around this concept, a burgeoning industry is developing around “microtasking,” dividing work up into small tasks that can be farmed out to workers. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, rolled out in 2005, allows users to post tasks to a platform where registered workers can accept and complete them for a small fee. When this paper was written, more than 195,000 tasks were available on Mechanical Turk.5

Such technologies may offer suitable possibilities for the public sector. Microtask, a Finnish cloud labor company, maintains Digitalkoot, a program that helps the Finnish National Library convert its image archives into digital text and correct existing errors. It does so with volunteered labor; participants simply play a game in which they are shown the image of a word and then must type it out to help a cartoon character cross a bridge. In doing so, they are turning scanned images into searchable text, greatly improving the search accuracy of old manuscripts.6 At present, more than 100,000 people have completed over 6 million microtasks associated with this project.7

As the pace of computing power and machine learning increases, professors Frank Levy and Richard Murnane contend that more tasks will move from human to computer processing.8 Skeptics need look no further than IBM’s Watson, a computer that can answer questions posed in natural language. In February 2011, Watson defeated two all-time champions of the quiz show Jeopardy! This was not solely a publicity stunt; IBM hopes to sell Watson to hospitals and call centers to help them answer questions from the public.9

Around the globe, more and more governments are looking to increase telework among employees. In 2010, the U.S. government passed legislation calling for more telework opportunities for government employees. Likewise, the Australian government, in order to attract and retain information and communications technology workers, instituted a teleworking policy in 2009 requiring agencies to implement flexible work plans.10 Other countries, including Norway and Germany, are also focusing on flexible work arrangements to improve public sector recruiting.11 In Canada, the government has an official telework policy that recognizes “changes are occurring in the public service workforce with a shift towards more knowledge workers,” and “encourages departments to implement telework arrangements.”12

Cloud definitions

Cloud computing: “Internet-based computing, whereby shared resources, software, and information are provided to computers and other devices on-demand, like electricity.”

— Amazon

Crowdsourcing: “Neologistic compound of crowd and outsourcing for the act of taking tasks traditionally performed by an employee or contractor, and outsourcing them to a group of people or community, through an "open call" to a large group of people (a crowd) asking for contributions.”

— Wikipedia

GovCloud: “A new model for government based on team collaboration, whereby workforce resources can be surged to provide services to government agencies on-demand.”

— GovLab

Source: Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane, The New Division of Labor: How Computers are Creating the Next Job Market, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 50.

Figure 1: Trends in routine and non-routine tasks in the U.S. 1960-200213

These are all powerful steps in the right direction for employees whose natural work rhythms are not locked into “9 to 5.” Some companies have taken telework one step further. British Telecom is pushing the concept of “agile working” through its Workstyle Project, where employees decide what work arrangements best suit them—rather than a rigid definition by location and hours. BT Workstyle is one of the largest flexible working projects in Europe, with over 11,000 home-based workers. BT has found that its “home-enabled” employees are, on average, 20 percent more productive than their office-based colleagues.14

Similarly, U.S. electronics retailer Best Buy experimented with a “Results Only Work Environment” (ROWE). In a ROWE, what matters is not whether employees are in their office, but rather that they complete their work and achieve measurable outcomes. In a ROWE, salaried employees must put in as much time as is actually needed to do their work—no more, no less.

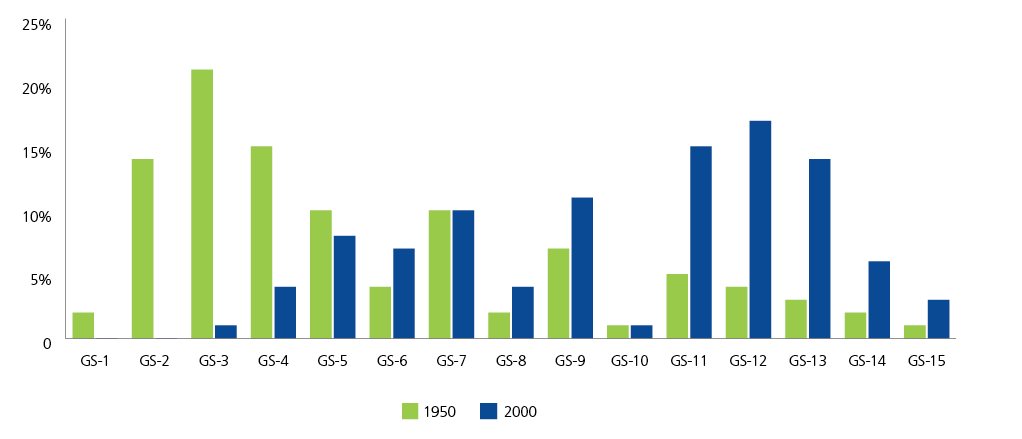

The decline in routine and manual tasks and the rise of new ways of working is not isolated to the private sector. In 1950, the U.S. federal workforce largely comprised clerks performing repetitive tasks. About 62 percent performed these tasks, while only 11 percent performed more “white-collar” work. By 2000, those relationships were reversed. Fifteen percent performed repetitive tasks, compared to 56 percent in the white-collar categories.16 Similarly, in 1944, the number of workers in the UK civil service considered “industrial” totaled 505,000. By 2003, this number fell to 18,200, with “non-industrial” workers reaching 538,000 in 2004.17 And in Canada, in 2006, knowledge-based workers represented 58 percent of federal workers in the Core Public Administration, up from 41 percent 11 years earlier.18

The swelling ranks of “non-industrial” government workers indicate a shift in public sector jobs toward creative, collaborative, and complex work. The workforce structure, however, designed for clerks of the last century, remains largely the same. With limited flexibility to distribute resources, governments often address change by creating new agencies and programs. This can be seen following major events like the outbreaks of the Avian flu and SARs in the past decade, 9/11, and the financial crisis of 2008.

Source: United States Office of Personnel Management, A Fresh Start for Federal Pay: A Case for Modernization (April 2002), p. 5. http://www.opm.gov/strategiccomp/whtpaper.pdf

Figure 2: The changing U.S. federal workforce 1950–200015

| Computing | Cloud characteristics | People |

| Cloud applications reside on shared hardware, accessible by many users. | Shared resources | Cloud workers reside in a central talent pool, accessible by many agencies. |

| Reducing the amount of overall hardware can reduce the cost of maintenance and associated personnel. | More cost effective (efficiency) | A government-wide cloud of workers could reduce the burden on each individual agency of maintaining and managing a large workforce. |

| Hardware is partitioned to allow for specific applications. This space is reclaimed once the application is no longer needed. | Virtualized | Cloud workers can be assigned to specific agencies to complete tasks/projects and then return to the central talent pool once the work is complete. |

| Access to data or applications in the cloud requires constant network connectivity. | Dependent on network connection | In order to access cloud resources, agencies must be part of the GovCloud system. |

| Co-locating software on hardware allows processing power to be quickly shifted from low-need to high-need programs without going through acquisition cycles to purchase additional hardware. | Dynamically scalable (more quickly shift resources) | By pooling workers in a government-wide cloud, resources can be quickly shifted from low-need to high-need programs and agencies, without requiring individual agencies to hire new workers or stand up new departments. |

| Rather than maintaining separate hardware for each user, cloud providers use centralized hardware. | Lower maintenance costs | Rather than each agency staffing and managing each anticipated business need, workers exist in a central cloud and are managed by a central HR function. |

Given increasing budgetary pressures and burgeoning national debts, the conventional model of creating new agencies or permanent structures in response to new challenges is unsustainable. This is exacerbated by our inability to accurately predict future needs and trends. Consider a 1968 Business Week article proclaiming that “the Japanese auto industry isn’t likely to carve out a big share of the market for itself,” or the president of Digital Equipment Corporation, who in 1977 said, “[t]here is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.”19

The world is full of experts who attempt to predict the future—and fail.20

Instead of endeavoring to predict the future, governments can choose to create a flexible workforce that can quickly adapt to future work requirements. To accomplish this, the government can learn from a game-changing concept in the technology world: cloud computing.

Major organizations and small startups alike increase their flexibility by sharing storage space, information, and resources in a “cloud,” allowing them to quickly scale resources up and down as needed. Why not apply the cloud model to people? The creation of a government-wide human cloud could provide significant benefits, including:

- The ability to apply resources when and where they are needed

- Increased knowledge flow across agencies and a new focus on broad, government-wide missions

- A reduction in the number of permanent programs

- Fewer structures that stifle creativity and interfere with the adoption of new technologies and innovations

A cloud-based government workforce or “GovCloud” could include workers who perform a range of creative, problem-focused work. Rather than being slotted into any single government agency, cloud workers would be true government-wide employees.

Breaking up bureaucracies

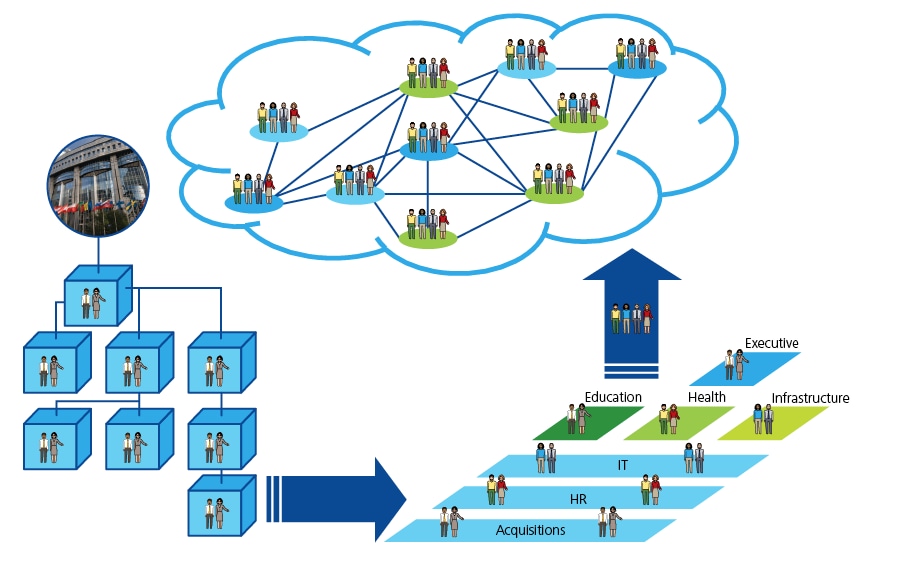

This section outlines the organizational structure of the GovCloud model, which rests on three main pillars: a cloud of government workers, thin executive agencies, and shared services.

The cloud

Most government workforce models tend to constrain workers by isolating them in separate agencies.

Consider the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in the United Kingdom and the subsequent slaughter of more than 6 million pigs, sheep, and cattle. The problem of an impacted food supply is complicated. In most countries, multiple agencies focus on agriculture, food production, and public health. In the United Kingdom, the army and even tourism ministries were impacted by the outbreak as agencies became overwhelmed by the number of animals in need of disposal and by the cordoning off of tourist areas to prevent the spread of the disease.Yet the structure of government agencies often confines employees to work in information silos, creating inherent operational inefficiencies. In a cloud workforce model, experts in each area could be pulled together to support remedies and propose coordinated corrective measures.

“I want someone saying: ‘Did you know that the Ministry of Justice is doing that, or could you piggy-back on what the communities department is doing, or had you thought about doing it in this way?’ You’ve got to get away from thinking about centralized command and control.” 21— Dame Helen Ghosh, Permanent Secretary, UK Home Office

The FedCloud model

The GovCloud model could become a new pillar of government, comprising permanent employees who undertake a wide variety of creative, problem-focused work. As needed, the GovCloud model could also take advantage of those outside government, including citizens looking for extra part-time work, full-time contractors, and individual consultants.

Cloud workers would vary in background and expertise but would exhibit traits of “free-agent” workers—self-sufficient, self-motivated employees who exhibit a strong loyalty to teams, colleagues, and clients. Daniel Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, argues that 33 million Americans—one-quarter of the workforce— already operate as free agents.22

According to the white paper, “Lessons of the Great Recession,” from Swiss staffing company Adecco, contingent workers—those who chose non-traditional employment arrangements23—are expected to eventually make up about 25 percent of the global workforce.24These more autonomous workers, according to Pink, are better suited to 21st-century work, and are more productive—even without traditional monetary incentives.25

Benefits of the cloud

The fluid nature of the cloud can provide significant benefits:

- Knowledge exchange: Avoids “trapping” knowledge within any single agency. The fluidity of the cloud allows for the quick connection of knowledge with the people who need it.

- Adaptability: Allows the government to concentrate resources where needed. The cloud would make federal work more adaptable and focused on cross-cutting outcomes.

- Collaboration: Encourages collaboration, whether in person or virtually, through the expanded use of video conferencing, collaborative tools, and electronic communication.

- Focus resources: Teams can be formed quickly and dissolved when their work is concluded, reducing the likelihood of government structures continuing to operate after they are no longer needed.26

The nature of the cloud—teams forming and dissolving as their tasks require—encourages workers to focus on specific project outcomes rather than ongoing operations.

| GovCloud: Problem-focused | |

| Types of work | Highly collaborative work such as policy creation, analyzing information, and reporting on data results |

| Types of roles | Program managers, economists, performance experts, public health specialists |

| Thin agencies: Mission-focused | |

| Types of work | Work requiring deep agency knowledge and collaboration, specialized scientific and medical work that may require a physical work location, face-to-face delivery of services or “frontline” work |

| Types of roles | Agency directors, inspectors, correction officers, passport office workers |

| Shared services: Support-focused | |

| Types of work | Traditional back-office support functions such as administration and technology support, facilities and logistics, and some HR functions |

| Types of roles | Human resource technicians, accounting technicians, administrative officers |

Benefits of thin agencies

Thin agency structures could lead to:

- Simplified mission accountability and responsibility

- A greater focus on mission outcomes rather than on back-office management

Benefits of shared services

Greater use of shared services could allow the federal government to:

- Reduce redundant back-office structures

- Consolidate real estate obligations and data centers

- Create a government-wide support structure capable of supporting the GovCloud

The need to support some ongoing missions will remain, of course. These missions will be carried out by thin agencies.

Under the cloud concept, federal agencies would remain focused on specific missions and ongoing oversight. These agencies, however, would become “thinner” as many of their knowledge workers transfer into the cloud. Thin agencies could also create opportunities to streamline organizations with overlapping missions.

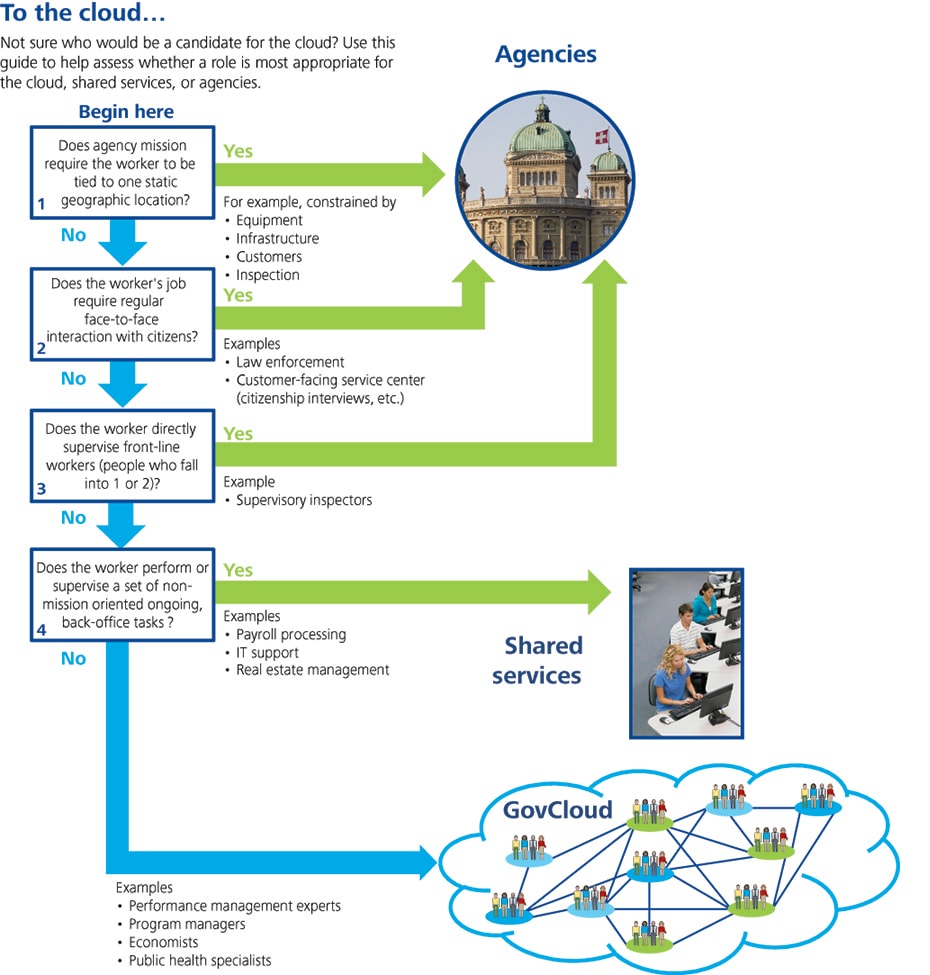

Employees working in thin agencies could fall into two main categories:

- Mission specialists: These are subject matter experts who possess knowledge central to the mission of the agency or tied to one geographic location. Examples include agency executives, policy experts, and others with knowledge that is closely aligned with the mission of a specific agency (e.g., foresters, tax code specialists). Mission specialists also could enter the cloud, based on the specific needs of other agencies.

- Frontline workers: These are employees who represent the “face” of government to citizens—law enforcement officers, investigators, regulators, entitlement providers, etc.—and who interact with citizens on a regular basis. As the nature of frontline work typically does not lend itself to the cloud, these employees would still align with individual agencies.

GovCloud could change the highest levels of public sector workers as we know them today. The Senior Executive Service in the United States, Permanent Secretaries and Directors General in the United Kingdom and Australia—all such senior officials could rotate between agencies, shared services, and the cloud, which would reflect the original intent behind many of these high-level offices: giving executives a breadth of experience in roles across government to help develop shared values and a broad perspective. An important benefit of rotation would be the ability to tap into cloud networks to assemble high-performing teams.

To further focus agencies on specific missions, many of their back-office support functions could be pulled into government-wide shared service arrangements.

The use of shared services in government has come and gone in waves—usually dictated by fiscal necessity. Most countries in Europe, as part of their e-government strategies, have placed increased focus of late on developing shared services, whether through an executive agency or a CIO, as well as working with EU coordination activities. And while the decentralized governments of some EU countries—such as Germany—make shared services more difficult, these countries are using states and agencies to pilot innovative approaches.27

Other efforts around the world include the U.S e-Government Act of 2002, which examined how technology could be used to cut costs and improve services. More recently, the New Zealand government appointed an advisory group in May 2011 to explore public sector reform to improve services and provide better value. In their report, “Better Public Services,” the advisory group recommended the use of shared services to improve effectiveness in a variety of government settings, including policy advice and real estate.29 Following up on this, three New Zealand agencies—the Department of the Prime Minister, the State Services Commission, and the Treasury—announced in December 2011 that they would share such corporate functions as human resources and information technology.30 And though shared services in Western Australia were shut down, other projects in South Australia are moving ahead and already showing savings.31

Shared Services Canada

In August 2011, the government of Canada announced the launch of Shared Services Canada, a program that seeks to streamline and identify savings in information technology. Among its first targets is something as mundane as email. But with more than 100 different email systems being used by government employees, the potential savings and boost to efficiency could be significant. Not only do these incompatible systems cost money by requiring individual departments to negotiate and maintain separate licenses and technical support, it also makes it difficult for government employees to communicate with one another and with the public. And with no single standard, ensuring the security of information transmitted over email becomes more challenging. Shared Services Canada will move the government to one email system as well as consolidate data centers and networks—ultimately looking for anticipated savings of between CA$100 million and CA$200 million annually.28

While the idea of using shared services is not a novel one, it is central to the GovCloud model. The GovCloud model envisions building upon effective practices and those shared services already in operation to deliver services like human resources, information technology, finance, and acquisitions government-wide. Workers in these shared services would include subject matter experts in areas like human resources and information technology, as well as generalists, who support routine business functions.

The potential for shared services continues to grow. As seen with IBM’s Watson and Microtask’s Digitalkoot, new technologies provide an opportunity to accelerate the automated delivery of basic services. Some agencies already have begun capitalizing on these trends. For example, NASA has moved its shared service center website to a secure government cloud, facilitating greater employee self-service and helping to reduce demand on finite call center resources.32

Who belongs in the cloud?

This decision tool is designed to help leaders determine which employees are appropriate for each of the three structures in the GovCloud model—the cloud, thin agencies, and shared services.

To the cloud...

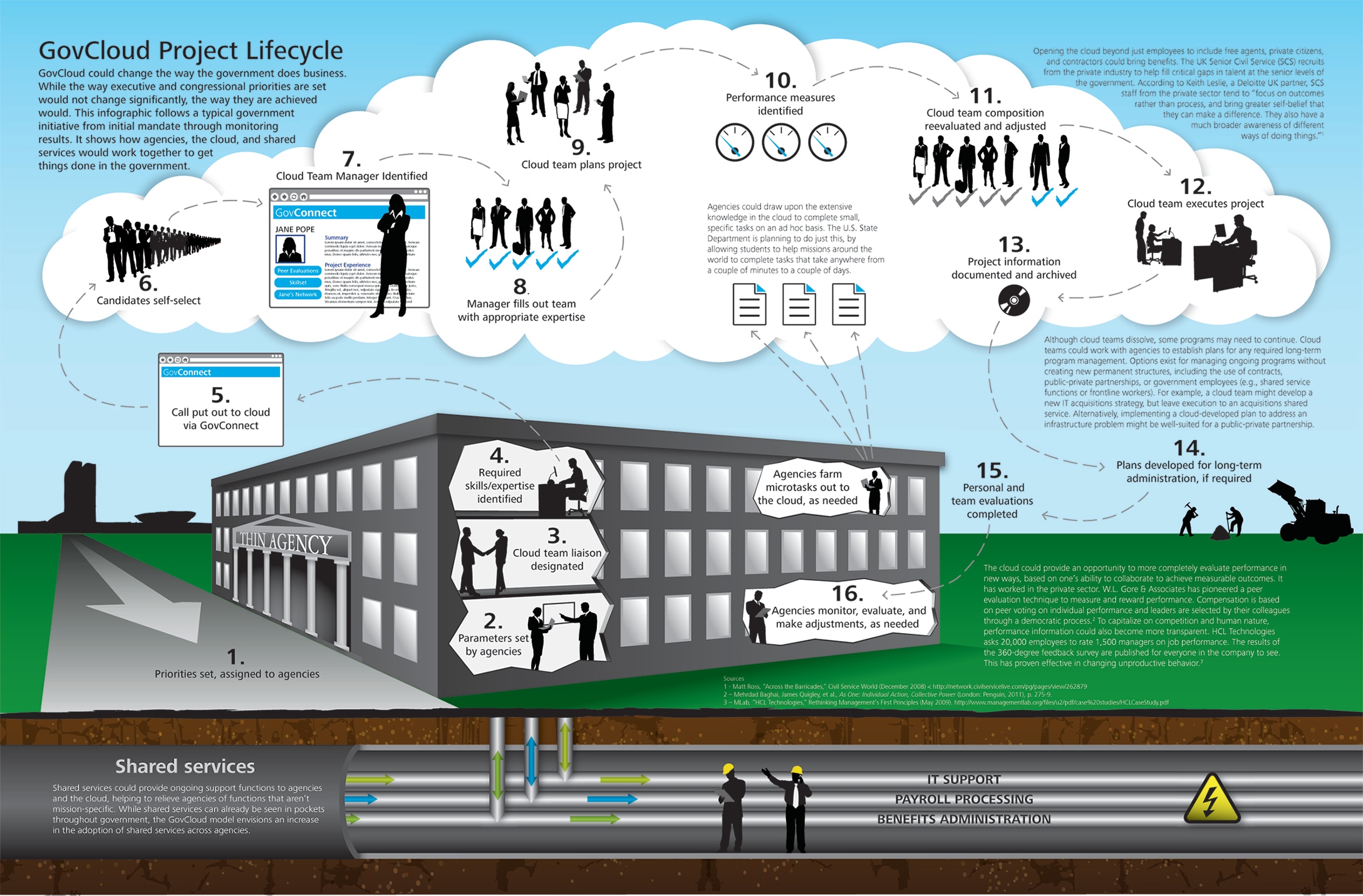

GovCloud Project Lifecycle

Reinventing HR

Managing employees in the cloud will require governments to reinvent human resource management. Individual and team performance evaluations, career development, pay structures, and benefits and pensions would need to change to support GovCloud. This section examines possibilities for HR reinvention, including performance management, career development, workplace flexibility, and benefits.

Performance and career management

Employees working in the cloud would require an alternative to determine pay and career advancement. The government could take its cues from the gaming world and evaluate cloud workers with a point system.

“The manager as we know it will disappear— to be replaced by a new sort of business operative whose expertise is assembling the right people for particular projects.” 33—Daniel Pink, author of Free-Agent Nation

An HR management system that incorporates the accumulation of experience points (XP) through effective work on cloud projects, training, education, and professional certifications could replace the tenure-centric models for cloud employees.

Why experience points (XP)?

- Rewards team players: Creates incentives not only to perform well as an individual but also to be a valuable collaborative team member and to continue one’s personal development

- Manages performance: Allows governments to shift focus from time in grade to a more holistic performance management scheme

- Fits work style: Capitalizes on the work style of Millennials, who value performance over tenure

- Creates right incentives: Takes advantage of “gamification” concepts to incentivize desired behaviors

- Lets workers own their careers: Allows workers to take personal ownership over the management of their careers, including their professional development and work-life integration

As employees accumulate XP, they could “level up” and take on additional responsibilities in future projects. Workers in the cloud could earn XP in four ways:

- Education and training: Employees earn XP based on advanced degrees, continuing education courses, and professional certification.

- Social capital: Employees could earn XP with high social capital scores based on their participation in GovCloud collaboration and networking.

- Leadership: taking on additional leadership responsibilities in cloud teams could raise individual XP scores.

- Projects: Projects in the cloud could be worth a certain number of XP, based on their scope and complexity and team performance. Project managers could award additional XP based on employee level, individual performance, and peer evaluation.

Breaking down silos: DEFRA

After some high-profile incidents—slow responses to outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease, flooding that may have been preventable, and a farming subsidy system that seemed to result in more chaos than aid—the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) was looking to reinvent itself. In 2006, the department launched DEFRA Renew. One of its key goals was to bring the department’s policymaking closer to actual delivery to create more responsive processes.

Organized, mainly by policy, with fixed teams, DEFRA had been unable to redeploy resources as needed in response to a crisis. As part of DEFRA Renew, a new operating model was implemented that used flexible resourcing where staff were assigned to specific projects for fixed periods. This allowed management to measure and build the required capabilities and competencies needed and to allocate resources efficiently to improve overall service quality. New roles were also created to support sustainable staff development and resource management in the new model.

To create buy-in for such a fundamental culture shift within the department, a facilitative approach to decision-making was employed. Change management programs and mentoring were extended to all levels of the department, including leadership. New mechanisms—such as approval panels for resources and the use of business cases—also worked to push changes among staff and promote collaborative behavior.

DEFRA Renew was widely recognized as a key enabler in the department meeting required efficiency improvement targets set by the UK government. DEFRA moved to a more project-based approach, with fewer staff in core teams. According to Dame Helen Ghosh, former Permanent Secretary of DEFRA, they could be more responsive now that “the management board won’t be made up of director generals with individual policy silos.”34

Just as XP could be gained through learning new skills, it could be lost in the following three ways:

- Failure to apply skills: Workers could earn XP for training, but lose these points if they do not use the resulting skills on projects.

- Down time: One would expect some cloud employees to be between projects at any given time, and indeed this provides the capacity to surge when demands require. That said, employees who spend too much time away from project work could lose XP.

- Poor project performance: Employees who receive less-than-satisfactory ratings on individual performance reviews, peer evaluations, or team performance could lose XP.

Salary and benefits

Any serious discussion about creating a new class of government employees requires a fresh look at employee benefits and compensation. For example, XP could be used to help determine workers’ salaries, but additional research into alternative pension and benefit programs is needed. While any discussion on compensation could be contentious, a healthy debate among stakeholders from across the government should be welcomed.

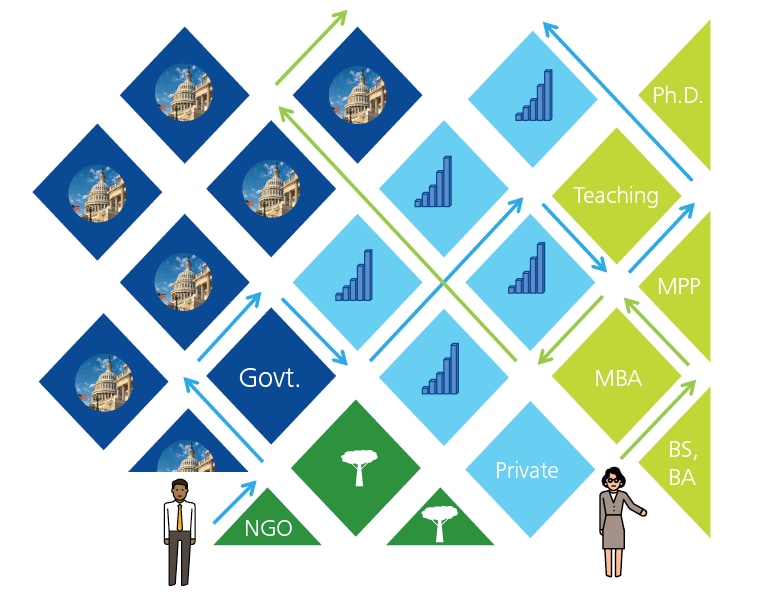

Career paths

As new roles emerge in the cloud, so too could new career paths. Career emphasis could move away from time served in a particular pay grade and toward milestones that are meaningful for employee development.

Each worker may have different career aspirations. For instance, not all workers aspire to management; some may seek to master a particular subject area instead. Career advancement in the cloud would not equate to moving up a ladder, but rather moving along a lattice.

Lattice GovCloud Model

Here’s how the lattice could work for Ian, who we met in the introduction.

- The early years: A few years after being hired into the human resources shared service straight out of school, Ian has been exposed to a wide variety of agencies. Through these interactions, he realizes he has become passionate about the field of social work.

- Seeking a change: Ian decides to leave federal service and pursue a master’s degree in social work, and then take a job at his state’s social services agency. After a few years, Ian accepts a position as director of a mid-sized non-profit.

- Returning to GovCloud: After years of running the non-profit, Ian begins thinking about government service again. He decides to join GovCloud by working just a few hours a week. After working part-time on projects that require social work experience, Ian decides to return full-time. To more effectively manage social programs, Ian seeks out all the performance measurement training he can find.

- Finding a niche: Ian becomes well versed in performance measurement, first for social programs, but he quickly learns how to apply those concepts elsewhere. When his social work experience isn’t needed, he can also lend performance measurement knowledge from the cloud.

- Winding down: As he nears retirement, Ian wants to help train the next generation of social workers by teaching one course per semester at a local university. However, he is able to remain connected to GovCloud and spend one or two days a week working with social programs and measuring the performance of other projects.

“Think of the lattice as a jungle gym. The best opportunities to broaden your experience may be lateral or even down. Look every which way and swing to opportunities.” Fortune— Pattie Sellers,

Cathleen Benko and Molly Anderson, the authors of The Corporate Lattice, argue that the corporate ladder is giving way to a lattice that accommodates flatter, more networked organizations; improves the integration of career and life; focuses on competencies rather than tenure; and helps increase workforce loyalty.35 The lattice metaphor allows employees to choose many ways to “get ahead.”

Learning

It is unlikely that all workers will thrive in the new GovCloud environment right out of the gate. As such, it would be important to assess a worker’s readiness before placing her in GovCloud and providing training on core competencies critical to cloud success. There could also be opportunities to start workers, especially those at earlier stages of a career, within an agency or shared service to build up expertise in some area before “graduating to the cloud.” Once in the cloud, new workers could be paired with mentors, who are more experienced, to help navigate the cloud experience itself.

There should be an emphasis on continuous learning in the cloud. It would be important for cloud workers to continue to refine their skills, develop additional expertise, and adapt to new ways of working. Not only could continuous learning affect workers’ career mobility by increasing the depth and breadth of their skills, but it could also impact their salary and level by increasing their XP.

Learning and development in the cloud could take on many themes of “next learning.” Next learning focuses on creating personalized learning experiences that leverage the latest technologies and collaborative communities to deliver education and learning programs that build knowledge bases and promote learning as a focus and passion, not just a checkbox in a career.36

To broaden cloud worker skills and the ability to handle multiple tasks and work on a variety of projects, cloud learning could include the following principles:37

- Video: The use of video learning could bring an in-person feel to trainings for cloud workers. Further, it could allow for more meaningful mentor relationships, even over long distances. This is an important component of a highly virtual workplace.

- Social and collaborative learning: Use the wisdom of the cloud (and beyond) to create a collaborative learning environment.

- Learning projects: In an environment where cloud workers are completing microtasks or participating in projects, design training to reflect this, helping to hone collaboration and other skills that will be important in the cloud.

- Learning and leading in a distributed workplace: Workers who ascend to positions of leadership will need more than the traditional essentials of leadership to get them there. They will need to learn how to motivate and manage employees in a distributed environment, which requires an emphasis on communication, accountability, trust, and performance.

- Building knowledge bases and connectivity for learning: Elective knowledge management will be critical in the Gov Cloud environment. This is just as important for training as for project information. Make knowledge gained in one area available elsewhere by tagging and promoting content for others to see. This can complement social learning by allowing users to bookmark or promote effective learning channels.

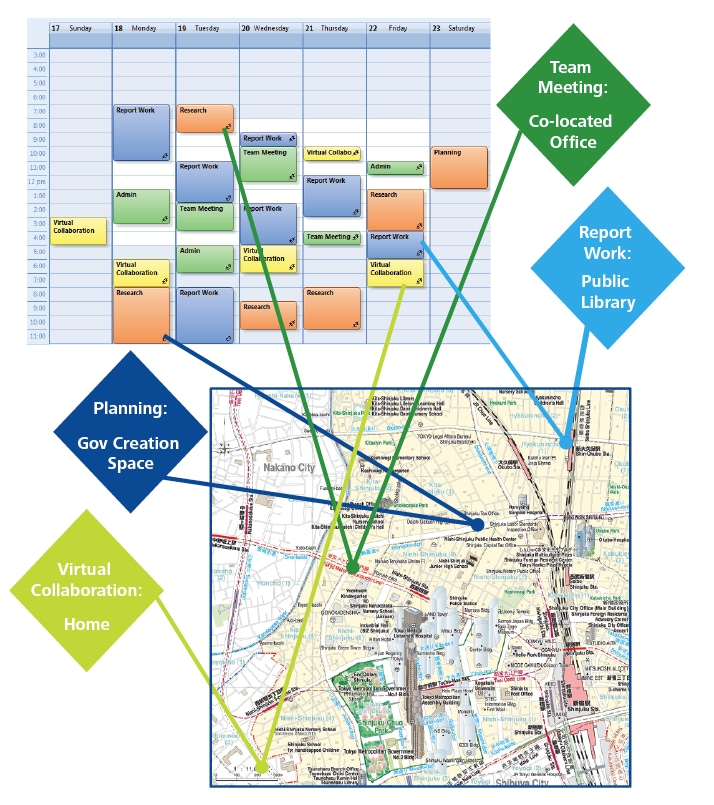

Workplace flexibility

In the cloud, careers and expertise will be built in new ways and work will be something we do, rather than a place we go to. As such, the cloud will give workers more control over their schedules and workloads. By creating a flexible workplace, governments could shed a significant amount of physical infrastructure and create shared workspaces. Many buildings could be converted into co-located spaces; teams could use collaboration spaces or videoconferencing centers.

Some workers might rarely set foot in a government building, instead conducting cloud tasks at home and interacting with project teams virtually. With advancing communications and mobile technology, distance no longer hinders collaboration. It no longer matters whether all workers are at an office between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.; what matters is whether project teams produce results and whether everyone contributes.

A more flexible workplace could also take advantage of resources governments might not otherwise have access to. Some retiring workers may not want to quit working altogether, and a flexible model could be an enticing way to keep their expertise on retainer. Alternatively, the model could take advantage of would-be government employees unwilling to relocate or unable to work a regular schedule. By increasing flexibility, governments could increase their available resource pool, allowing agencies to access the skills and knowledge they need, when they need it. For an example of how a retiree could interact with the cloud, see Appendix C: National Security Case Study.

U.S. State Department pilots the cloud

Don’t think governments will ever take to the cloud? At the U.S. Department of State, the idea could soon be a reality. The Office of eDiplomacy is preparing to pilot a cloud component to its e-internship model for American students as part of the Virtual Student Foreign Service (VSFS), beginning this year. The VSFS currently offers e-internships to U.S. university students of multiple month duration. By using a new micro-volunteering platform, State Department offices and embassies around the world will be able to create non-classified tasks that take anywhere from a couple of minutes to a couple of days to complete. Each task will be tagged by region and/or issue and will automatically populate the profiles of students who have indicated those interests. Students can then select the tasks that interest them the most or that fit into their schedule.

To see that the most pressing work is performed first, offices and embassies will be able to prioritize their tasks, so critical items appear at the top of the queue. Imagine a small embassy preparing for a high-profile, multilateral meeting. The preparations for such an event could be daunting for a small staff. The power of the cloud could augment an individual embassy’s capacity to prepare for a major event and ensure that related items are performed ahead of those that are less critical.

While there are plenty of incentives for participating in the VSFS micro-volunteering platform—from an impressive line on a student’s resume to the chance to make a difference by working on topics of interest—thought is being put into how to creatively incent high performance. One idea is to simply invoke students’ competitive spirit. Competition could be encouraged by a monthly leader board, which results in bragging rights and, potentially, even a low-cost, but high-impact reward. Transparency is also key to competition: with ratings available to State Department staff and other cloud interns and the ability to make short thank you notes from embassies publicly available, interns would be keen to make a good impression.

The potential applications of this type of program are significant. Imagine if offices throughout the State Department could tap into the language and cultural expertise of the thousands of foreign national staff members around the globe. Providing a platform for those employees to contribute even a small amount of time to discreet tasks that require their expertise could unlock a world of knowledge.38

Taking the first steps

Creating the GovCloud model will require bold leadership and the ideas and initiatives of entrepreneurial executives. While a GovCloud model may be years in the making, agencies can begin adopting cloud concepts today.

- Build collaboration spaces: Make interoffice collaboration easier. Create physical spaces in your office where employees can casually spend time sharing information across departments. Provide employees with several hours per week to devote to collaborative efforts with other areas of the agency that interest them.

- Rotate your people: Embrace the Millennials’ aptitude for change. Create a rotational program that allows staff members to work across departments and specialties. As your organization realizes the value of a broader perspective, you can pursue rotation among agencies or even secondments (rotations between the nonprofit, private, and public sectors).

- Start a volunteer cloud: Plant the seeds for the cloud by allowing workers to seek tasks beyond their current responsibilities. Start by providing a platform for managers to post issues or problems they need help in solving. Allow employees to help with projects or tasks that interest them. This will allow them to expand their networks, build new skills, and chase their passions.

- Pilot a GovCloud: Only experience will bring people to understand the power of the cloud. A few agencies could bring the cloud to life by moving resources to a pilot cloud workforce. This would allow them to document lessons learned and determine the viability of the cloud on a wider scale. Use the GovCloud decision tree to help determine who could thrive in the cloud.

One step toward the cloud: Secondments and temporary project teams

The Ontario Public Service (OPS) has significant experience with building as-needed project teams to support specific, high-priority projects using staff brought in from other departments for short-term secondments. What allows this to work is a flexible HR framework that supports and facilitates staff secondments as developmental opportunities. The HR framework contributes to a culture that recognizes and rewards the experience secondees gain in these high-profile work assignments. OPS employees are generally eager to participate in these projects and are typically rewarded throughout their careers for the skills they acquire.39

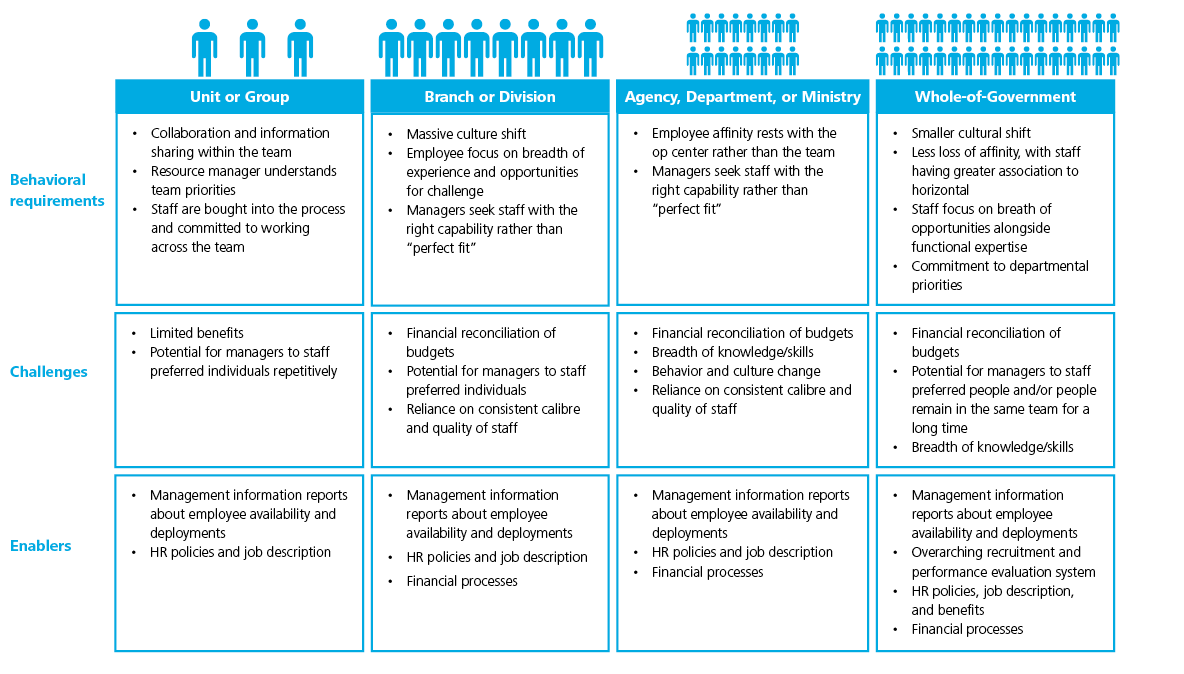

Implementing GovCloud

The GovCloud concept is designed to be versatile as well as applicable to a wide range of entities. Depending on your organization, government executives wishing to employ GovCloud may choose to apply the concept first to a unit, before expanding to other branches or divisions, entire agencies, or the whole of government.

Often, GovCloud principles are most effectively implemented as part of a larger reform program within a particular agency—as with the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs’ Renew program, as described earlier in this report. On a smaller scale, the UK Cabinet Office used flexible resourcing (FR) in its Economic Reform Group (ERG), with a staff of about 400, as part of its cost-reduction plans. Using a simple database that it had developed and a strong program of communications, FR is now used and embraced by all core ERG employees, with strong, clear ownership from the top—another key implementation factor. Says Ian Watmore, the UK Cabinet Office’s former permanent secretary, FR means “we are able to deploy people much more quickly to priority projects.”40

Figure 3 outlines how GovCloud can apply to a variety of organizations.

Figure 3: An illustrative continuum for applying the GovCloud concept to public sector organizations

The road ahead

Most government workforces haven’t undergone a broad restructuring in decades. In that time, the world has been transformed by computers, the Internet, and mobile communications.

To respond to a variety of challenges, governments have created scores of new organizations. However, in today’s world of budget cuts and increased fiscal scrutiny, the constant creation of new, permanent structures is not sustainable.

The GovCloud model could offer a new way to use government resources. A cloud of government-wide workers could coalesce into project-based teams to solve problems and separate when their work is done. This could allow governments to concentrate resources when and where they are needed. By using this model in conjunction with thinner agencies and shared services, governments can reduce back-office redundancies and let agencies focus on their core missions.

This model capitalizes on the work preferences of Millennials—the future government workforce—who value career growth over job security or compensation.41 The GovCloud model allows employees to gain a variety of experiences in a shorter amount of time and to self-select their career direction.

To support GovCloud, governments could establish the processes by which cloud teams would form, work, and dissolve. New ways to evaluate performance and help workers gain skills and build careers should be considered. Today’s employee classification system stresses job descriptions and time in service; this could be transformed with an XP model that emphasizes the individual’s ownership of his or her career.

The GovCloud model will undoubtedly be controversial. Many stakeholders, from governing bodies to public employee unions, must weigh in to shape the future government workforce. The transition to a cloud model will not happen overnight or maybe even in the next five years, but the conversation starts today.