Capturing value from the smart packaging revolution

15 October 2018

Smart packaging offers significant opportunities and a real risk of disruption. Innovative business models and practices can help overcome challenges and maximize the value of smart packaging applications.

A shipment of high-end skin care products leaves its offshore production facility, and an embedded multifunction sensor in the pallet tracks the location of the product as it moves through multiple transport modes, letting the consumer packaged goods company alert retail partners to the expected time of arrival. At a domestic warehouse, the pallet unfortunately slips off a skid and is partly damaged, the time and location of the shock being recorded by the sensor for later apportionment of responsibility and improvement of handling processes. The products arrive at the retail store where scanners read anti-tamper intelligent labels on each package to confirm that the products have not been tampered with and are nonpirated. At home, a sensor in the cap monitors the consumer’s usage and uploads the data to a smart home hub, which reorders the product automatically as it runs low.

This vignette, although not a real-world example, is a compilation of individual smart packaging functionalities already in the market or in development, and underscores the potential of smart packaging to transform supply chains, product integrity, and customer experience. Senior executives in operations, marketing, finance, IT, and a range of other functions in consumer packaged goods, industrial goods, retail, and packaging would be well-advised to take notice.

Learn More

Explore the retail and consumer products collection

Subscribe to receive consumer business content

Smart packaging solutions offer out-of-the-box business value

Somewhere between US$5 trillion and US$10 trillion worth of consumables are sold globally each year and the vast majority of them are packaged in some way, generating a packaging market of US$424 billion in 2016.1 Yet packaging remains a secondary consideration for manufacturers, brands, and retailers alike. It is often an overlooked and underutilized aspect of product design that packs immense value for all stakeholders. Packaging with enhanced functionality, by way of new technologies, new materials, and thoughtful design—smart packaging—has enormous potential not only to create value, but also to disrupt traditional business models.

Results of our survey of over 400 business leaders revealed that smart packaging, and in particular connected packaging, is indeed on the radar of senior executives, and is attracting significant investment across the value chain as companies seek to exploit the opportunity (see sidebar, “Research methodology”). Survey results validated that connected packaging solutions tend to fall into three broad categories—inventory and life cycle management, product integrity, and user experience—and that the first two are currently attracting the lion’s share of investment.

Research methodology

This report is partly based on the findings of a survey conducted by Deloitte between November 2017 and February 2018. Survey respondents included 425 North American business executives from 12 industries. More than 70 percent of respondents represented companies with revenues of more than US$1 billion. Almost 90 percent were in senior management roles. The margin of error for the entire data set is plus or minus 5–6 percentage points.

While smart packaging is an umbrella term used to denote different types of packaging systems (design-led, active, and connected; table 1), the survey focused on what we refer to in this article as connected packaging and the business opportunity it offers.

Smart packaging is still emerging, but cannot be ignored, as it presents both significant opportunities and a real risk of disruption (figure 1). It generated revenues of US$23.5 billion in 2015, and is expected to grow 11 percent annually, reaching US$39.7 billion by 2020.2 Businesses are looking at packaging as a possible holistic solution to transform the way they deliver, sell, and use products. Market leaders across industries are embracing innovative smart packaging applications, particularly of the connected type, that generate and leverage data to make better business decisions and delight the customer.

The potential upside for smart packaging participants is large, but they face at least four types of challenges: commercial, legal, technological, and organizational. A review of the market and utility of smart packaging will help set the premise for key challenges in large-scale adoption of these applications and the possible solutions.

Defining the smart packaging space

Most of the existing smart packaging solutions are in the “active” realm, using advanced chemistry and materials to offer corrosion/moisture control or thermochromatic capabilities, primarily for food and beverages, health care, and personal care consumer products. Connected packaging, which can communicate with other packages or the internet, is still a relatively untapped opportunity, with simple bar coding and RFIDs used increasingly for tracking and tracing package location in the supply chain. Survey results indicate that adoption of connected packaging varies by industry, with consumer packaged goods, and manufacturing and industrial companies expressing the highest levels of interest. However, connected packaging is still in the initial stages of growth and no application or industry is close to reaching maturity.

The smart packaging industry is still highly fragmented, as both large- and small-to-medium-sized enterprises continue to focus on narrow, one-off solutions, as opposed to delivering an integrated, cohesive offering for large-scale implementation. The interconnected nature of the ecosystem and the wide array of participants from infrastructure providers to packagers, brands, retailers, and consumers have prevented smart packaging from accelerating rapidly.

Innovation in the space has been driven primarily by small startups, and solutions have yet to achieve significant scale. Dominant industrywide Internet of Things (IoT) standards have yet to take hold, much like the days preceding the arrival of Bluetooth or Wi-Fi in local wireless networks. The cost of sensorization and connectivity is still high, even though it has declined significantly in recent years and we expect it to drop further (figure 2).

How are businesses using smart packaging?

Market leaders from several industries are embracing innovative smart packaging applications primarily to address three types of business issues:

- Inventory and life cycle management

- Product integrity

- User experience

Inventory and life cycle management

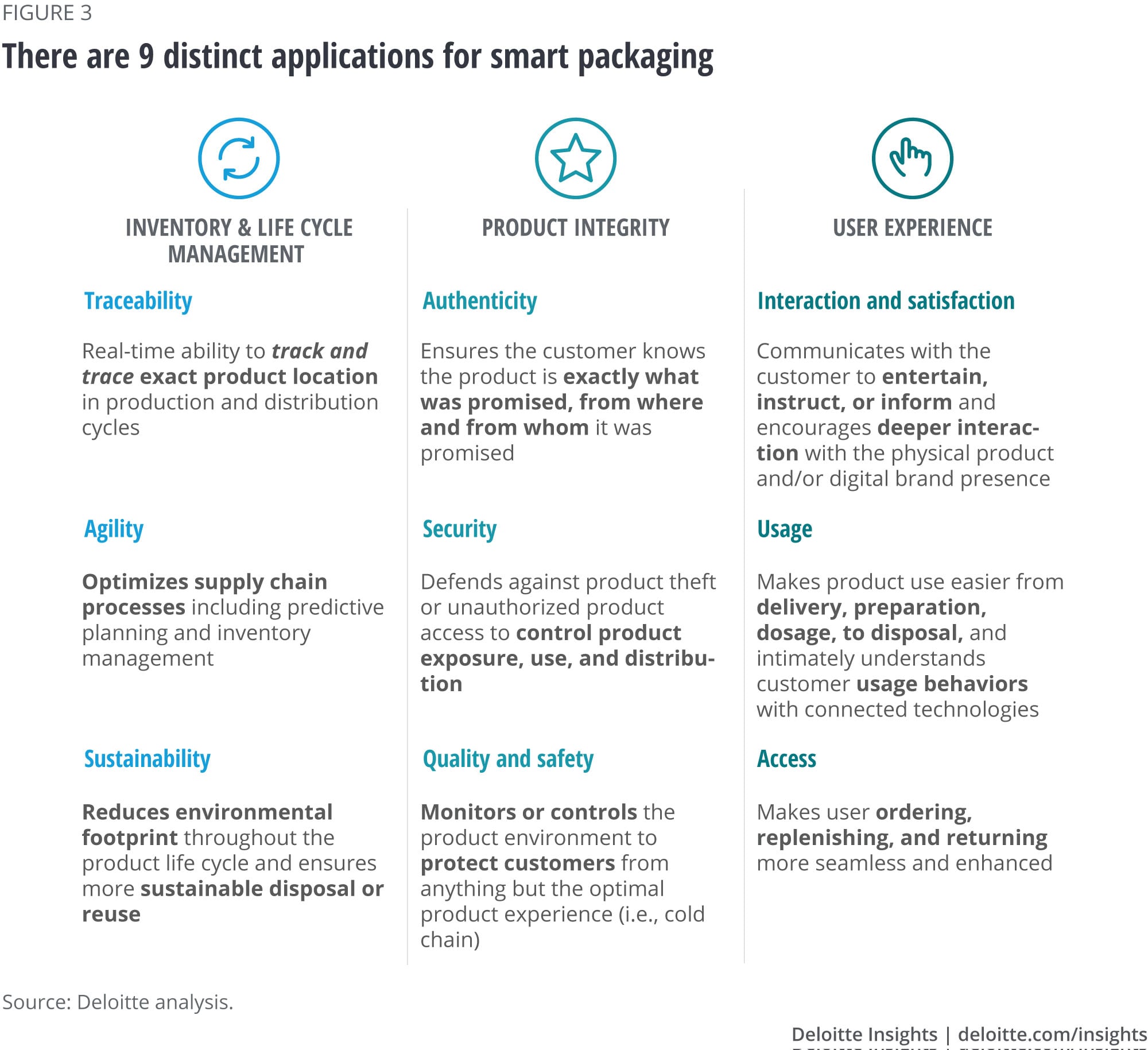

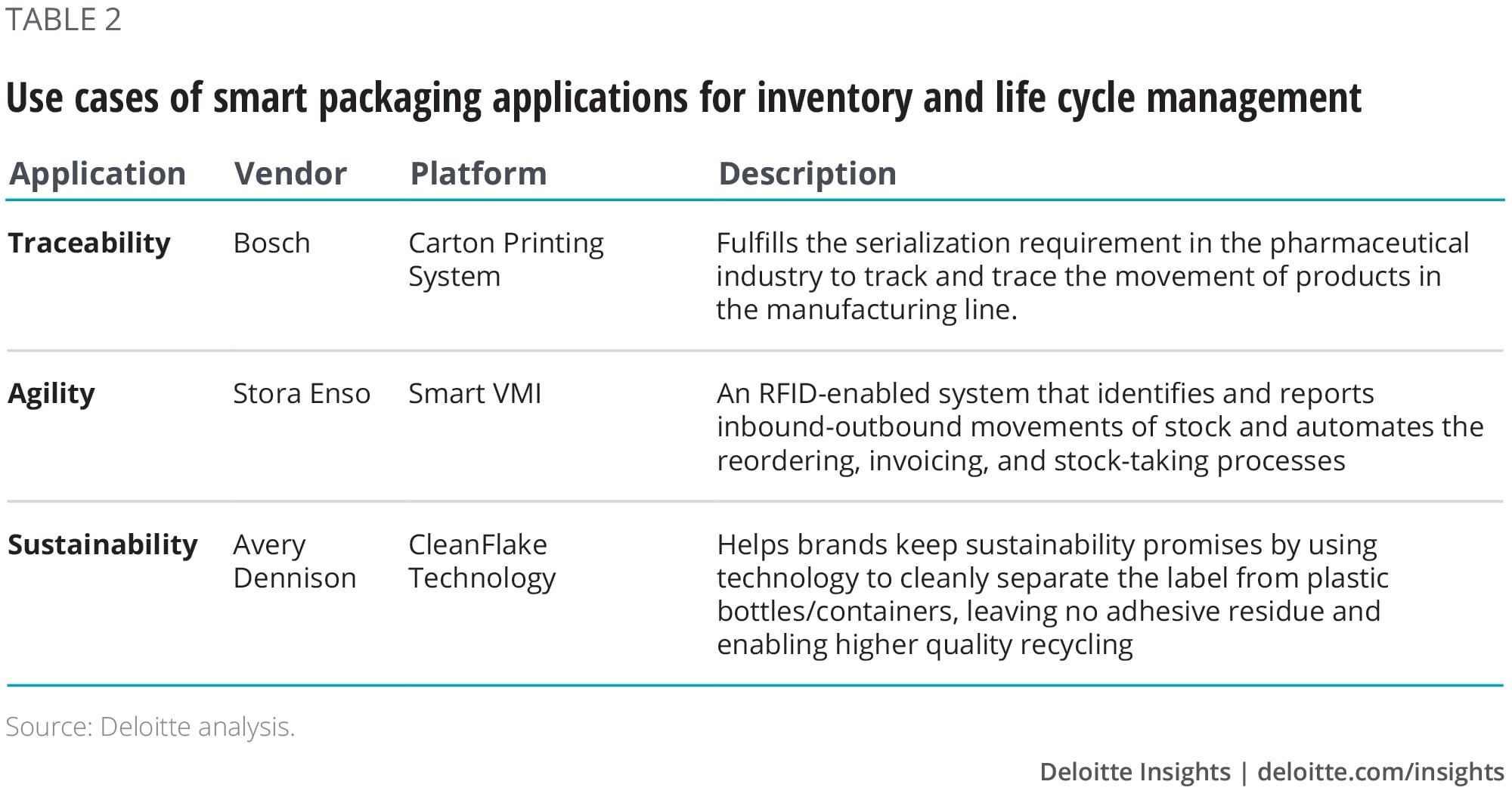

Packaging can provide solutions to common supply chain problems, including sourcing raw materials from suppliers, managing the supply chain, and delivering products to the final customer. We have categorized these applications into three sub-areas—traceability, agility, and sustainability, which are detailed in figure 3— and listed out some genuine use cases in table 2.

Product integrity

Packaging can be a valuable layer of defense against internal and external threats to product integrity. The value at stake is large. Food retailers estimate that 31 percent of all food products are discarded due to spoilage, totaling US$146 billion in losses, and in the area of counterfeit goods, smart packaging could help to combat losses valued at more than US$460 billion.3

These losses for brands and rising quality concerns among consumers are driving adoption of new technology-enabled anti-counterfeiting applications. Blockchain technology is an increasingly important component of these applications, as it allows producers and consumers to create a secure, unalterable record of a product’s provenance and path to market. Some retailers are exploring smart packages that include a device to record information on a blockchain regarding the contents of the package, its environmental condition, and its location, among other data points.

The three key categories of product integrity applications are authenticity, security, and quality, which are explained in figure 3. Table 3 lists out some use cases.

User experience

Packaging can enhance user satisfaction by making the actual product use occasion more engaging, efficient, or informative, as well as by providing valuable consumer insights to brand owners and retailers. Companies can earn greater brand loyalty by using the three main applications of user experience, as mentioned in figure 3. Table 4 lists out some use cases.

Smart packaging is arriving in waves

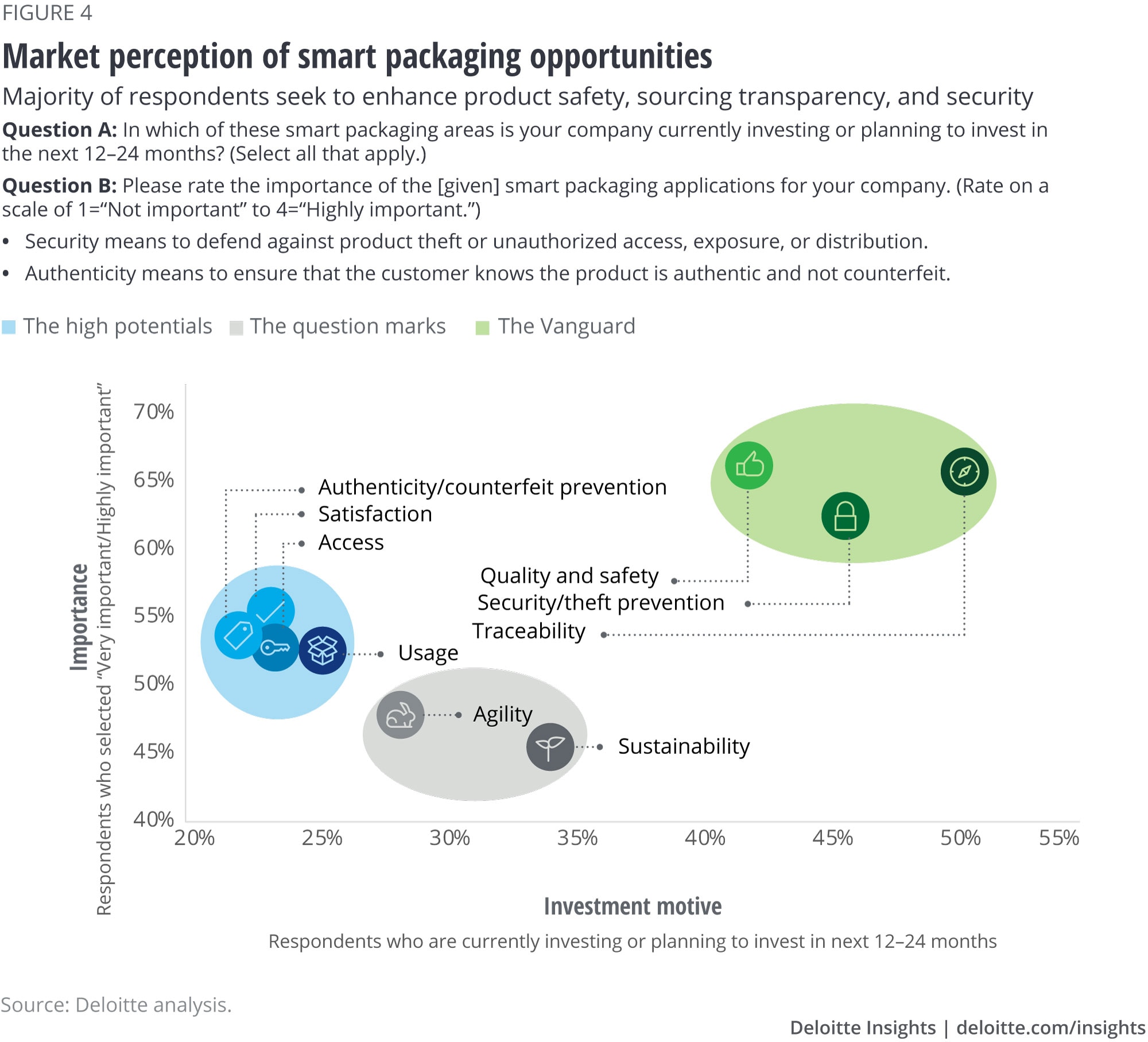

Our analysis of the smart packaging space suggests that the different applications are arriving in waves, as certain applications gain broader and earlier traction than others, which was corroborated by survey results. Figure 4 maps the perceived strategic importance of nine smart packaging applications against the intention to invest in each in the coming years.

The figure illustrates the several applications (the Vanguard) that are seen as important and receive the most investment, addressing track-and-trace and product integrity concerns. Several “high-potential” applications driving the customer experience, though seen as very/highly important by over 50 percent of respondents, are receiving much lower levels of investment. This disconnect is likely due to the complexity of designing and executing solutions that require the collection of end-user data. Given the importance of these solutions, however, we expect these “high potential” problems to be resolved soon and investment to follow.

Smart packaging offers significant opportunities and a real risk of disruption

Smart packaging cannot be ignored because not only can it create enormous value, it can disrupt a number of players in the system. Smart packaging, with revenues of US$23.5 billion in 2015, makes up only a small percentage of the global packaging industry estimated at US$424 billion.4 Nonetheless, it is expected to grow quickly, largely because it is seen as a mechanism for solving a number of high-value business problems.

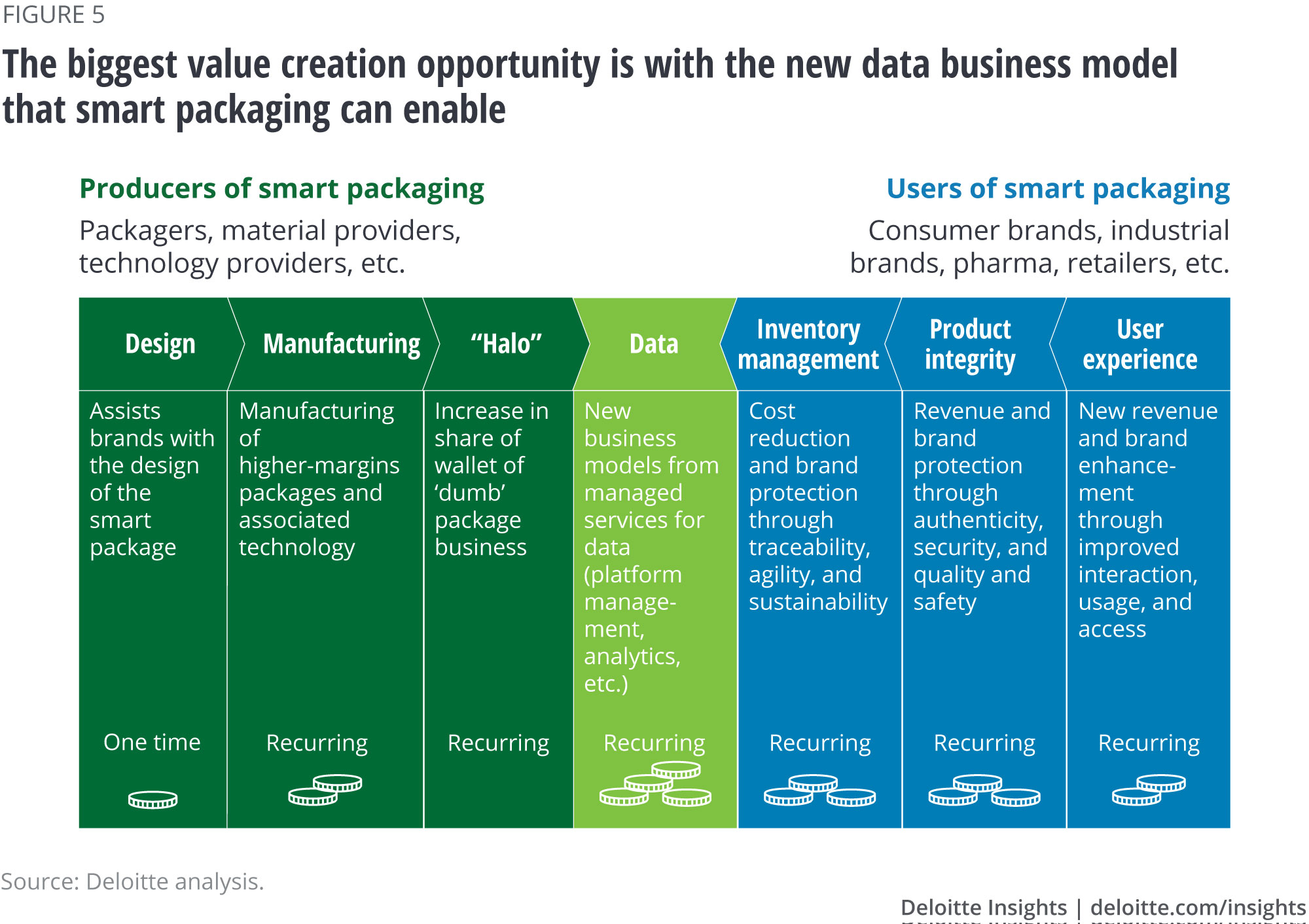

It is clear that both producers and users of smart packaging can benefit from it, as outlined in figure 5. Producers, which include packagers, material producers, and technology providers, stand to gain by designing and/or manufacturing all or part of the solutions. Many have also witnessed gains to their traditional (“nonsmart”) business lines just from proposing more sophisticated smart packaging ideas to their customers, regardless of whether those ideas get commercial traction. We call this the “halo” effect.

For users of smart packaging (brands, retailers, and end consumers), value creation comes in the form of the three sets of applications described earlier—greater supply chain efficiency, enhanced product integrity, and superior customer engagement. Most important, however, is the value pocket in the middle, i.e., the new set of revenue streams unleashed by the data spun off by smart packages. This is a battleground where the producers and users will meet to determine who will win the spoils. We believe both sides can lay claim to it if they position themselves well, so there is a scenario where the spoils are equitably shared.

With the potential value creation, comes disruption. For instance, if packagers are not able to participate in driving the increasing intelligence of packages, they risk getting marginalized as commodity material providers. Consumer packaged goods producers and other brand owners can create unprecedented customer intimacy through connected solutions, but if their competitors move first, they could be locked out of key customer relationships. Retailers could improve supply chain efficiency, guarantee product integrity, and engage consumers, but could also get disintermediated by brands that can now build direct digital relationships with consumers through the package. Technology players can set industry standards and use this advantage as a platform for data and associated revenue streams, but could get left behind if the standards they back aren’t selected. For all players in the ecosystem, the potential benefits and risks are substantial.

Winning in smart packaging will demand ingenuity and creativity

While there is clear value in smart packaging applications, many challenges exist to large-scale adoption, and overcoming them will require participants to experiment with innovative business models and new ways of doing business.

Commercial challenges

Monetization

“Yes, but how will we make money?” is the common refrain from companies exploring smart packaging, and especially from packagers. Packaging firms provide the critical substrates and engineered materials for packages, but are generally not seen as value-added participants in data-enabled packaging, so have struggled to share in the upside. A leading packaging company codeveloped a plastic “smart ticket” for an entertainment event company that geo-tracked customers through event spaces, automatically added and deducted credits, and allowed automated purchases, among other things. The entertainment company generated significant customer satisfaction and new understanding of customer behavior, which drove increased traffic and sales, while the packaging company earned “cost plus” on the materials. In other words, the company created value, but failed to capture it.

To be able to capture value in smart packaging, companies must first be able to identify their unique, differentiated contribution to the smart packaging solution. This contribution gives them a seat at the “value-add table” and a stronger claim to getting access to data generated by the smart solution. Data is key to new revenue streams and often to premium pricing. For packagers, this contribution could involve providing access to key customers, or as in one case, proprietary knowledge about food preservation chemistry critical to a smart anti-spoil packaging solution. Second, companies should design a profit model that gives them a share of the newly created value. It’s important to leave behind the traditional cost-per-pound commodity trap and experiment with multiple new pricing approaches. In many cases, this will require risk-sharing and coinvestment until the value of the solution is demonstrated. Potential models include full investment in prototype development in return for sharing in incremental sales of the end-product and/or in any data generated by the solution.

Prohibitive costs

Certain connected packaging solutions (such as track-and-trace applications) rely on inexpensive package-level technologies like bar codes, QR codes, and even passive RFIDs. More intelligent solutions, however, that use active RFID, geo-locate, track temperature and shock, or interact with consumers require sensor technologies that are by and large too expensive to use on the primary (single unit) package, making certain smart applications cost-prohibitive. Almost 30 percent of survey respondents listed business case economics as a key barrier to smart packaging. The good news is that the cost of these sensors is declining (figure 2) and will likely at some point be low enough to place on everyday consumer goods. In the meantime, however, brands, retailers, and packagers are using the lower-cost smart technologies on primary packages, and experimenting with more powerful sensors on secondary/tertiary/pallet-level packaging, or on the primary packaging of high-value goods such as perfumes and liquor.

Legal challenges

Regulatory/Privacy concerns

As in any context where information is collected regarding third parties, smart packaging risks butting up against privacy laws. This challenge has become particularly acute in the light of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, whose principles many experts believe may soon also arrive in the United States. Smart packaging solutions that do not collect end-consumer data (for example, track-and-trace solutions focused on supply chain efficiency) should face fewer privacy hurdles, and solution providers should be able to manage privacy concerns in large part through direct contractual arrangements with their business-to-business partners. Smart solutions that do collect consumer data may pose more of a challenge and will have to be engineered in the light of these emerging regulations, possibly utilizing such protective mechanisms as opt-ins or sanitizing, blinding, and aggregating the data.

Data ownership

With a typical smart packaging application depending on the interplay among multiple different stakeholders, the question of who owns the data that the packaging generates will need to be addressed. Typically, in the business-to-consumer realm, brand owners or retailers will claim ownership of the consumer relationship and, therefore, any data regarding the consumer. However, other players, including packagers, have successfully laid claim to this data in two ways—first, as already mentioned, by bringing some unique value contribution to the solution that allows them bargain for rights to the data, and second, by cleverly realizing that they do not need “ownership” of the data, so much as they need “access” to it. For example, a large packaging company let the retailer “own” the data generated by smart cardboard displays in the store, but successfully secured access to the point-of-sale data linked to sales from the display, and could use that data to prove the value of smart displays. Ownership is in fact a bundle of rights over property, including the ability to use, improve, destroy, sell, and rent, among other things. To get value from data, one often only needs one of these rights. The lesson, therefore, is that one should not feel obliged to negotiate for ownership of data, so much as for the few specific rights needed to capture value.

Technology challenges

Technology standardization

Unified IoT technology standards have yet to take root. Several IoT protocol areas, such as infrastructure, identification, transport, and data protocols, each have multiple standards vying for supremacy; these include 6LowPAN, uCode, and mDNS. This creates challenges and opportunities. The main challenge is the lack of a single standard around which all parties can build solutions, which prevents the IoT in general, and smart packaging in particular, from scaling rapidly. As a result, smart packaging players must take a chance by either spreading small technology bets across multiple hands or betting big on one potential winner.

At the same time, the fragmentation of IoT technical standards creates an opportunity for key nontechnology players such as retailers, brands, and packagers to help shape the IoT standards of the future. Companies may want to get involved with standards-setting organizations for this reason.

Organizational challenges

Collaborations

Smart packaging is a solution that requires collaboration among a number of organizations—consumer and industrial product manufacturers, material substrate providers, packagers, retailers, transporters, and a small universe of technology providers (figure 6). Tellingly, over one quarter of survey respondents cited “lack of relevant technology capabilities” as a major barrier to smart packaging success. Very few players have all the necessary components in house. Smart packaging, therefore, relies on the creation and effective maintenance of an ecosystem of partners. The upside is access to a new, asset-light business model. The challenge is the complexity of securing and managing a web of capabilities you don’t own. To be able to excel in smart packaging, companies will have to disproportionately invest in their partnering capabilities, learning how to form various types of alliances to quickly add and drop critical assets and capabilities.

Agile innovation

Not only must smart packaging participants be nimble with their external assets, they need to be agile in configuring their internal innovation assets as well. This does not come easily to most firms, which continue to move all initiatives through rigorous discounted cash flow-driven business case processes. However, given that the rules of competitive advantage are still taking shape, smart packaging will involve agile innovation techniques—developing ideas, rapidly forming teams, jury-rigging prototypes, market-testing them, seeing what works, and iterating.

Nestle, for example, solidified its early lead in single-serve packaged coffee (Nespresso) by pursuing several ingenious channel innovations in quick succession to scale quickly. It started by selling to grocery stores, then expanded to selling directly to consumers through the Nespresso club, and finally to selling through own-brand boutique premium retail stores.

In sum, there are a few emerging truths in the smart packaging arena. First, the upside potential is large, as smart packaging is poised to solve numerous weighty business issues from stock-outs to counterfeiting to product spoilage to customer satisfaction and retention. Second, smart packaging is organizing around a set of nine broad applications, which are arriving in waves—supply chain efficiency is leading the charge, followed closely by product integrity and customer engagement. Third, participants in the traditional packaging space ignore smart packaging at their peril since the downside of missing out could be disruption of their existing business model, and irrelevance. Lastly, to capture the rewards and avoid irrelevance, participants should be bold and creative. Bold plays and new business models are a virtual certainty in the data-enabled world of smart packaging.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.