The burdens of the past has been saved

The burdens of the past Report 4 of the 2013 Shift Index series

12 November 2013

While individuals are eagerly embracing new knowledge-sharing technologies, our research suggests that outdated institutional structures continue to inhibit organizational knowledge flows.

The burdens of the past

Long-term trends help to tell a story. In the case of the 2013 Shift Index, the story centers on the puzzling discrepancy in technology adoption between individuals and organizations. In their personal lives, individuals are enthusiastically harnessing the power of rapid technological advances and the information flows they unleash to create more value. Why then do so many corporations and institutions seem unable to effectively embrace technological advances that speed up the flow of knowledge?

That’s the critical question raised by the 2013 Shift Index (see sidebar “The Shift Index”), a set of measurements designed to complement the numerous indices tracking the short-term facts and figures of a rolling business cycle. Collectively, these metrics clearly show that we are in the early stages of an enormous transformation that we call the Big Shift. The business environment is changing in a more fundamental way than short-term, boom-and-gloom market and employment numbers show.

The Shift Index

We developed the Shift Index to help executives understand and take advantage of the long-term forces of change shaping the US economy. First released in 2009 and updated annually, the Shift Index tracks 25 metrics across more than 40 years, providing a comprehensive view of underlying trends not captured by short-term economic indicators. These metrics and the relative rates of change between them highlight the evolution and impact of important long-term developments in technology and public policy.

The 25 metrics are divided into three indices that measure the three waves of change in what we call the Big Shift in the global business environment:

- The Foundation index involves changes to the fundamentals of the business landscape catalyzed by advances in the digital technology infrastructure and reinforced by liberalizing public policy. Changes in the Foundation metrics have systematically reduced barriers to entry and movement.

- The Flow index looks at the flows of knowledge, capital, and talent—the key drivers of performance enabled by the foundational advances—as well as the amplifiers of these flows. Flow metrics tend to lag Foundation metrics because of the time required to understand and develop new practices consistent with foundational changes.

- The Impact index captures the consequences of long-term trends on competition, volatility, and performance across industries. Impact metrics will change as firms begin to figure out how to participate in the knowledge, capital, and talent flows across institutional and geographic boundaries.

For more information about the Shift Index methodology, please refer to www.deloitte.com/us/shiftindex.

Driving these changes is the continuing exponential improvement in the cost performance of three core digital technologies: computing power, storage, and bandwidth. As a result, new products and services hit the market faster than ever. Individuals who adopt these products and use them in unexpected ways then generate more products and services, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation. Coupled with public policies driving economic liberalization, the advances in and adoption of new technologies have resulted in fierce competition and a shift of power from institutions to individuals. The 2013 Shift Index finds executive turnover at an all-time high, brand disloyalty and consumer power continuing to rise, and the compensation gap between “creative talent”1 and other workers widening (figures 25–28).

In this fluid, competitive environment, a few institutions and ecosystems are creating new sources of value and discovering new ways to thrive. The data analytics company Palantir has built, from the ground up, the ability to help organizations answer their toughest questions through previously impossible data manipulations and visualizations.2 DPR Construction, recognizing that innovation requires employees to learn faster together, has built a customized online meeting space—an “idea marketplace” where employees share, debate, and develop ideas across organizational boundaries.3 Google combined rapidly advancing technologies to create self-driving cars that see the world with much greater accuracy than human drivers do and can respond to changes much more quickly and precisely.4

Such stories, unfortunately, are not common. Companies like these are on the edge. Traditional rank-and-file firms, where the bulk of the world’s human and material resources still reside, lag behind in many areas. The continued downward trend in return on assets (ROA) among US public companies—which has declined to one-quarter of its level in 19655 (a few years before the invention of the microprocessor)—is one indication of this lag. Companies are working harder than in the past, only to generate lower returns from their assets. Still pursuing goals of greater efficiency and predictability, the value they create diminishes as they strive to squeeze every last bit of variance out of operations.

This focus on efficiency and predictability, however appropriate it may be in a relatively stable business environment, is no longer a virtue. Rapid technological advances and new competition from unexpected quarters make forecasts less accurate—and less valuable. Thus, the world of the Big Shift demands resilience and learning over routine and the status quo. Scalable learning trumps scalable efficiency, and participating effectively in knowledge flows within and across organizational boundaries becomes a critical skill.

Fortunately, thanks to the unprecedented cost-performance improvement in computing power, storage, and bandwidth, the communications tools that can enable rapid learning and effective knowledge-sharing are widely available and improving every day. And on an individual level, it hasn’t taken long for us to adjust our habits and adopt a myriad of tools that make communication easier, faster, and cheaper. At home and in transit, we use the Internet to find information, entertain ourselves, and create new content. Mobile phones and social tools give us always-on access to our contacts. Constant connectivity drives ever-higher mobile data traffic.

By and large, people are proving to be highly proactive in adopting newer and better communication tools, willing to change as soon as a lower-cost, higher-value solution appears. Consider the communications metrics in the 2013 Shift Index (figures 10–11): The emergence of over-the-top (OTT) messaging service applications like WhatsApp and MessageMe means that wireless minutes and SMS messaging have likely peaked in absolute terms, while the other means of communication are growing more rapidly.6

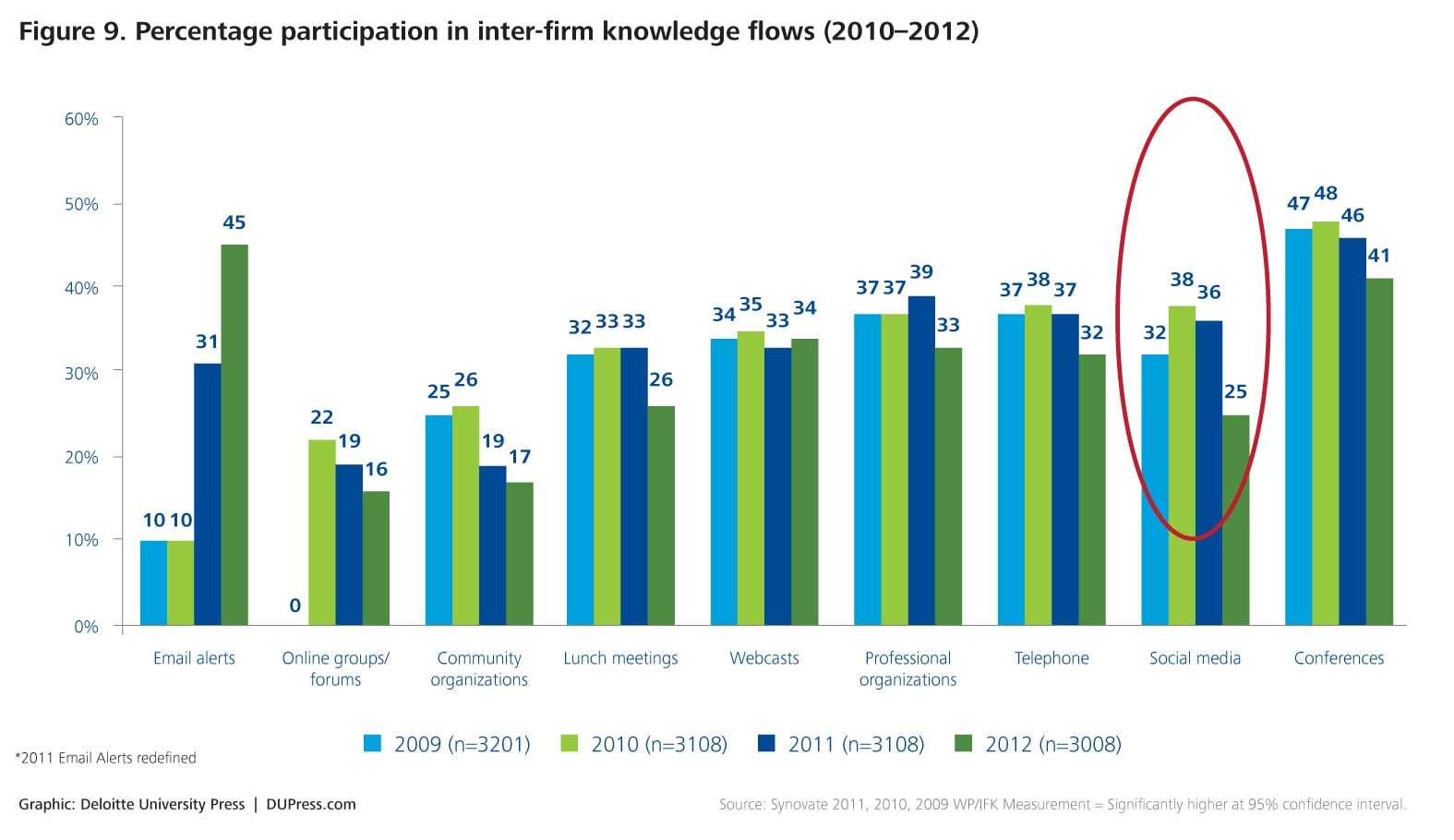

Yet our data also indicate that the ways we connect and share in our personal lives have not carried over to how we connect, innovate, and learn from each other professionally. This is in spite of the fact that the Internet and Web 2.0 tools are driving a convergence of the personal and the professional. More and more people are using technology to work anytime, anywhere; the traditional boundary between “work” and “life” is rapidly dissolving. One might expect social media and other knowledge-sharing tools to be as widely used within as well as outside the workplace. But rather than increasing, the integration of such tools into the work environment is actually declining. In 2012, participation in work-related online forums, professional and community organizations, and social media networks decreased from their 2011 levels. Corporate social media usage, in fact, is lower in 2012 than it was in 2009, with participation rates in social media below 20 percent across most levels of the organization (figure 9)—including middle management (18 percent), lower-level management (13 percent), and non-management (9 percent).

Given the increased availability of knowledge-sharing tools and many companies’ expressed intent to deploy them, these results seem surprising. After all, in a July 2013 Deloitte and MIT Sloan Management Review report, executives across all industries indicated that they considered social business to be important.7 Numerous organizations have demonstrated how social media can help workers resolve exceptions, share practices, crowdsource solutions, and discover expertise wherever it resides. So why has its adoption been so slow at many companies? Executives in the Deloitte-MIT Sloan Management study cited barriers such as the absence of an overall strategy and the lack of a proven business case.8 But we suspect that a more fundamental force may be at work: the historical value accorded to efficiency and controllability by businesses accustomed to a less changeable, less transparent world.

To better understand this year’s Shift Index, as well as to learn about ways to begin to create and capture value in this environment, we invite you to take a deeper look at our 2013 Shift Index research reports:

Unlocking the passion of the explorer

From exponential technologies to exponential innovation

Success or struggle: ROA as a true measure of business performance

Lessons from the edge: What companies can learn from a tribe in the Amazon

The increasing turnover rate among executives (figure 28) also hurts businesses by undermining the ability of a given leadership team to develop long-term, trust-based relationships on behalf of the organization. Whether executives are using their increased bargaining power to find better opportunities elsewhere or simply buckling under mounting performance pressure, the shortening of their average tenure at any particular organization compromises the organization’s ability to make a lasting impact on its chosen industrial or functional domain.In a world where change was relatively slow and steady, leaders felt confident that they could predict the future with a fair degree of accuracy. Goals were framed well in advance, and their achievement was viewed as virtually certain—as long as everyone did his or her job. Jobs, in turn, were well defined and organized to support processes engineered to deliver precise outcomes. In such a world, efficiency and repeatability are virtues, and flexibility can be seen as wasteful and irrelevant. For institutions designed to maximize efficiency and execute tightly scripted processes at scale, cultivating flows of knowledge may seem like a distraction.

Nor, in the era before the technologically driven, widespread cross-pollination of ideas, was sharing information necessarily an advantage. Guarding knowledge, rather than sharing it to pursue potential mutual gain, was seen as central to creating value. Workers were trained to protect company information, and any collaboration with those outside of the organization was closely monitored or even discouraged, as such connections could be deemed risky. Most innovation was driven from within the company’s four walls, often without customer feedback or interaction.

What happens when companies continue to try to fit new technologies and practices into old business models and rationales? The 2013 Shift Index’s metrics paint a sobering picture of the results. Economy-wide ROA has fallen to a quarter of its 1965 level, stock prices are increasingly volatile, and firms continue to lose their leadership positions at an increasing rate (figures 20–23).

Our worker passion analysis shows that the widespread belief that passion pertains only to the select few in our workforce can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Passion, as the Shift Index measures it, remains low: Only 11 percent of the US workforce is passionate about their work (figure 15). This is not a promising sign, as worker passion is one of the major factors that lead to accelerated learning and performance improvement.

It is true that one group of workers—the segment sometimes known as “creative talent”—continues to reap a disproportionate share of the value created by the Big Shift. The skills of these individuals, who include scientists, designers, and management executives, are in high demand, and companies are fighting to acquire and retain them. Their scarcity and importance are reflected in the increasing relative compensation of this group (figure 27). But this phenomenon comes at an obvious cost to employers, who are paying more and more to retain skills that are getting harder and harder to find.

Simply put, there is a growing mismatch between the old frameworks and practices that many companies use and the structures and capabilities required to be successful in a rapidly changing environment. Legacy corporate practices are holding businesses back from fully participating in new opportunities. Perhaps even more importantly, companies are becoming significant bottlenecks to the efforts of all of us to harness more of the power of pull—the ability to get better faster as more and more people participate in pull platforms that help us to draw out people and resources when we need them and where we need them.

As long as our institutions continue to resist the Big Shift, the journey ahead will remain stressful and pressure-packed. As workers and as leaders, our lives will not get easier unless we decide to shape, rather than simply adapt to, the future. By working together to reengineer our institutions, we have an opportunity to unleash more of our potential and tap into the increasing returns made possible by ever-expanding flows of knowledge. We can choose to participate in flows of knowledge rather than hold tightly to static stocks of information whose value is rapidly diminishing. Certain institutions are already starting: by scaling edges (a very different and much more promising approach to large-scale organizational transformation); redesigning their work environments; cultivating worker passion; and bringing smaller, proven successes back to the core of their business.

In the context of the Big Shift, what is the rationale for the corporation, and how will the future corporation operate? What would an institution redefined from the bottom up, with the goal of scalable learning, look like? Our future institutions may look very different from today’s, with faster learning and a renewed focus on our customers and ecosystems, all interacting to seize the opportunities created by the Big Shift.

2013 Shift Index metrics

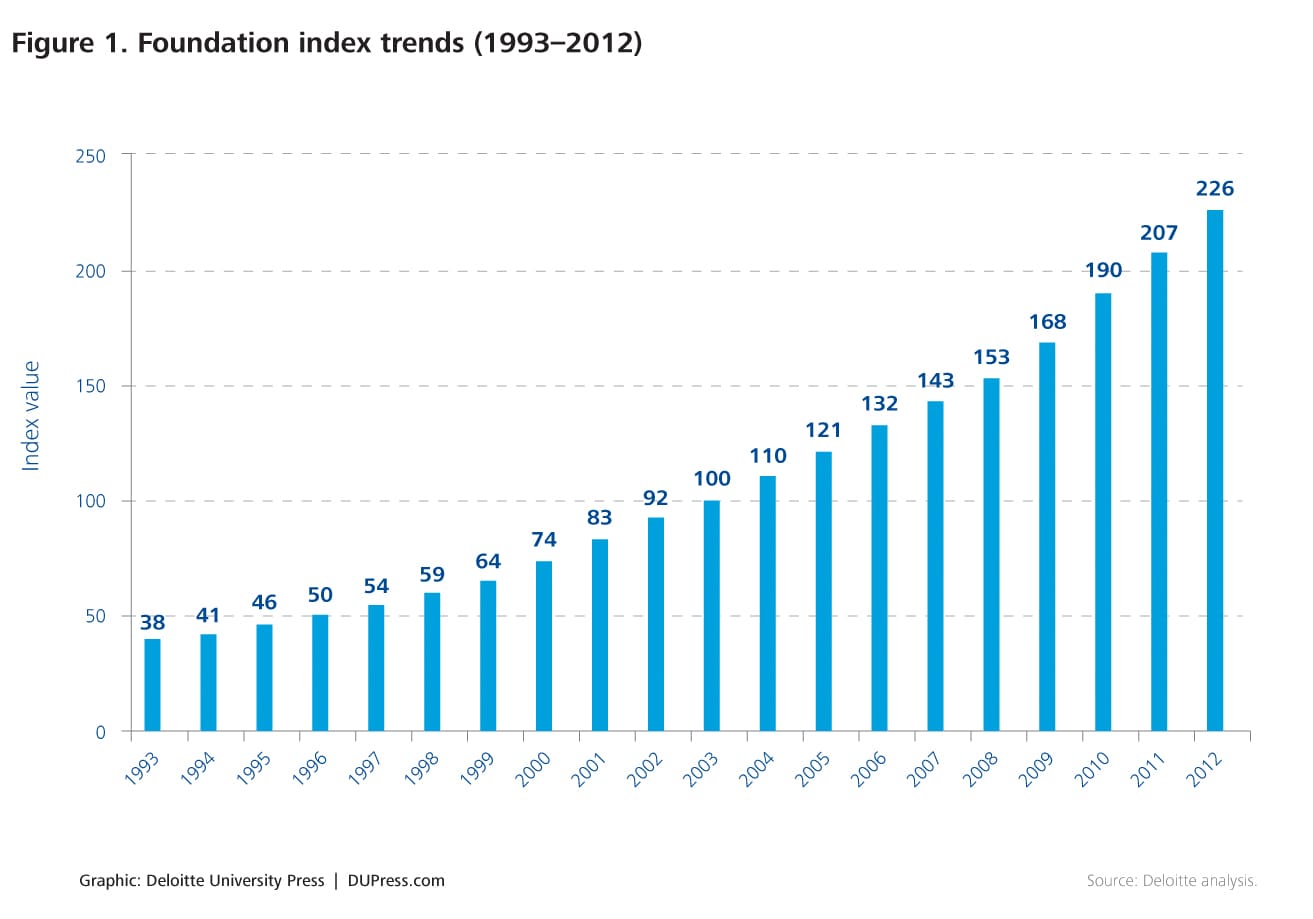

The Shift Index consists of three sub-indices that measure the rate of change in today’s business environment: the Foundation index, the Flow index, and the Impact index. The Big Shift consists of three waves. We are currently in the first wave of the shift (measured by the Foundation index) and are struggling to fully embrace the second wave (captured in the Flow index).

Foundation index

The Foundation index measures changes that are fundamental to the business landscape and are catalyzed by the emergence and spread of digital technology infrastructure and reinforced by long-term public policy shifts toward economic liberalization. The metrics in the Foundation index provide leading indicators for potential change in other areas.

Technology performance

Computing

The cost of computing power has decreased from $222 per million transistors in 1992 to $0.06 per million transistors in 2012. The decreasing cost/performance curve enables the computational power at the core of the digital infrastructure.

Digital storage

The cost of data storage has decreased from $569 per gigabyte of storage in 1992 to $0.03 per gigabyte in 2012. The decreasing cost/performance of digital storage enables the creation of more and richer digital information.

Bandwidth

The cost of Internet bandwidth has decreased from $1,245 per 1,000 Mbps in 1999 to $23 per 1000 Mbps in 2012. Declining cost/performance of bandwidth enables faster collection and transfer of data to facilitate richer connections and interactions.

Infrastructure penetration

Internet users

More people are using the Internet. From 1990 to 2012, the percentage of the US population accessing the Internet at least once a month grew from near 0 percent to 71 percent. Widespread use of the Internet enables greater sharing of information and resources.

Wireless subscriptions

More people are connected to digital infrastructure via mobile devices. From 1989 to 2012, the percentage of active wireless subscriptions compared to the US population grew from 1 percent to 100 percent, meaning there are now as many wireless subscriptions as there are people (although this does not mean each individual has a subscription). Smartphones made up 41 percent of the subscriptions in 2012.9 Widespread connectivity enables the sharing of data, information, and knowledge from nearly any geographic location.

Public policy

Economic freedom

The Index of Economic Freedom, a compilation of 10 indicators measured by the Heritage Foundation, is a proxy for public policies that promote open markets and the movement of capital, labor, product, and resources. Since 1995, the upward trend for the United States has been driven primarily by gains in investment freedom, financial freedom, trade freedom, and business freedom (4 of the index’s 10 components). Greater economic freedom increases competition and collaboration. In recent years, economic freedom has dropped significantly, in part due to increases in the size of the government.

Flow index

The Flow index measures the key performance drivers—flows of knowledge, capital, and talent—unleashed by the forces measured in the Foundation index. These flows are enabled by the rapidly advancing digital infrastructure and the general trend toward policy liberalization. Worker passion and social media activities amplify the flows. In the Big Shift, stocks of knowledge are less valuable and knowledge flows more important. While individuals take advantage of flows, institutions lag behind.

Virtual flows

Inter-firm knowledge flows

Although overall participation in knowledge-sharing activities that extend beyond organizational boundaries has not changed significantly between 2009 and 2012, workers are slowly changing the types of activities they participate in. While conferences are still common, the percentage of Deloitte survey respondents who use email alerts grew fastest, from 10 percent in 2009 to 45 percent in 2012. Participation in social media has dropped significantly between 2011 and 2012.

Wireless activity

Mobile devices are increasingly important for connectivity and access. Growth in SMS volume (158 percent compound annual growth rate [CAGR]) far exceeds that of wireless minutes (32 percent CAGR). In recent years, however, SMS volume has declined as a result of cheaper over-the-top (OTT) messaging applications (WhatsApp, MessageMe, Google Talk, Viber) and social media-based chat.

Internet activity

Internet traffic for the top 20 highest-capacity US routes has grown exponentially since 1993. In 2012, the average traffic rose to 6,237 gigabytes/second.

Physical flows

Migration of people to creative cities

Migration to the 10 cities ranked as most creative (based on the methodology developed by Richard Florida in his book The Rise of the Creative Class – Revisited) has increased faster than to the least creative cities. The gap between migration rates for these cities is increasing as people seek productive and enriching interactions in the physical world.

Travel volume

Despite better tools to connect digitally, people continue to seek face-to-face interactions. Over the past two decades, passenger travel volume has increased 63 percent and continues to rise. Physical interactions facilitate the transfer of tacit knowledge more readily than other means.

Movement of capital

The absolute amount of capital moving between countries has trended upward for the past 30 years. However, foreign direct investment (FDI) is impacted by many factors, including relative tax rates, interest rates, inflation, and protectionist policies—all of which can be quite volatile year to year.

Flow amplifiers

Worker passion

In a 2012 survey of 3,008 full-time US workers, only 11 percent of respondents exhibited all three attributes of worker passion—commitment to domain, questing, and connecting dispositions. Forty-five percent displayed one or two attributes. The results are not surprising; many institutions were designed for predictability, with inflexible, tightly integrated processes to minimize variances to plan.10

Social media activity

Social media has gained importance quickly. From 2007 to 2012, the time users spend on social media relative to the total amount of time they spend on the Internet grew from 7.4 percent to 13.9 percent, although it decreased slightly from 2011 to 2012. This decrease might reflect the use of mobile devices, rather than personal computers (PCs), for social media; non-PC use is not captured in the metric. This type of multi-way communication opens up opportunities to share knowledge and collaborate.

Impact index

The Impact index demonstrates the consequences of the Big Shift; thus, it is a lagging indicator. Individuals, able to quickly adopt new technologies and knowledge flows, are benefiting from the forces of the Big Shift as both consumers and creative talent. Companies, on the other hand, are struggling to evolve their efficiency-based legacy processes and practices to turn the challenges into opportunities.

Markets

Competitive intensity

Competitive intensity is inversely related to industry concentration (as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index or HHI). Before 1995, industry concentration had trended downward for 30 years, indicating a steady increase in competitive intensity. Despite ticking upward in recent years, industry concentration is still less than half of what it was in 1965.

Labor productivity

As a whole, productivity in the US economy has steadily improved for nearly five decades, from 45.3 in 1965 to 110.8 in 2012 (as measured by the Tornqvist aggregation, which shows how effectively economic inputs are converted into output).

Stock price volatility

Over the last 40 years, stock prices have become more volatile. This volatility can be seen as a reflection of investors’ reactions to increasingly volatile global events and greater uncertainty about the future.

Firms

Asset profitability

The aggregate ROA of US firms fell to a quarter of its 1965 levels in 2012. To increase—or even maintain—asset profitability, firms must find new ways to generate value from their assets.

ROA performance gap

The continuing ROA gap between top performers and bottom performers is not unexpected. It is significant, however, that even for the top quartile, ROA has declined from 12.9 percent in 1965 to 9.7 percent in 2012. The bottom quartile has declined more—from 1.2 percent in 1965 to -11.5 percent in 2012.

Firm topple rate

It is increasingly difficult for companies to sustain performance. Between 1965 and 2012, the topple rate (the rate at which companies change ranks) for all companies with more than $100 million in net sales increased as competition exposed low performers and ate away at returns. Recently, the topple rate has fallen after spiking in 2008. The increase in government support after the Great Recession may explain this reduction.

Shareholder value gap

Over the long term, the upper quartile of firms—the “winners”—have only slightly increased the rate of return to shareholders. Meanwhile, in the lower quartile, firms are destroying shareholder value at a faster rate.

People

Higher scores indicate more consumer power. Across most consumer categories, consumers’ perception of their power is increasing. Even at the low end—newspapers and cable/satellite TV—the balance still favors the consumer.

Brand disloyalty

Higher scores indicate higher brand disloyalty. Consumers continue to become less loyal to brands. Among the categories surveyed, brand disloyalty was highest in airlines, hotels, and home entertainment. Brand loyalty was higher in the soft drink, newspaper, and magazine categories.

Returns to talent

Workers in the creative class, as defined by Richard Florida, are reaping relatively more rewards (in the form of compensation) than the rest of the US labor force. The compensation gap between the creative class and the rest of the workforce has steadily widened over the past 10 years.

Executive turnover

Over the long term, executives are leaving their positions (resigning, retiring, or joining different companies) at an increasing rate. Since 2010, however, the executive turnover rate has accelerated, especially for banking and financial institutions. This acceleration may be caused by increasing performance pressures as the financial industry recovers from the recession. The increased turnover may also reflect the effects of pent-up demand as executives changed companies in a recovering job market. In addition, increased visibility into job opportunities via LinkedIn and other sites may also contribute to greater turnover.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.