Get set, grow: But are you ready? Optimize organic growth readiness by understanding the practices of overperformers

23 minute read

15 August 2019

Assessing growth readiness can help build a robust agenda for organic growth—and help achieve it. Our growth readiness framework can help diagnose if you’re ready to grow, improve the activities and capabilities that matter, and optimize organic growth readiness.

Introduction

Growth, particularly organic growth, is the lifeblood of organizations. Organic growth, which uses a company’s internal resources to increase revenue, may be slower to achieve than inorganic growth, which is attributable to takeovers or M&A, but it can frequently generate more value. Organic growth can allow companies to expand at a comfortable pace, adapting their business models and structures along the way. It can also enable them to circumvent the cost takeout requirements and integration challenges associated with growth through M&A. A company focused on organic growth sends powerful signals to investors and talent alike about its health, its ability to innovate, and its potential future performance. Understandably then, achieving organic growth is a priority for many top management teams.

However, our research suggests that many companies are leaving value on the table when it comes to organic growth. They often have hidden blind spots around where and how to look for growth opportunities and select the best ones. They also can face biases and weaknesses in developing and executing strategies to exploit them, especially moving resources at scale and speed to such opportunities. They may not be fully ready to grow, and this can inhibit them from achieving their full organic growth potential.

They may not be fully ready to grow, and this can inhibit them from achieving their full organic growth potential.

Learn More

Explore the revenue growth collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

So, how can top management diagnose if and where they have such blind spots? What are the activities, capabilities, and practices that underpin organic growth and how can they improve on them? How can they optimize growth readiness? And most of all, what steps can they take to achieve greater organic growth?

Typically, one of the first steps to achieving greater organic growth is setting out a robust growth agenda. But before that, management teams should assess their growth readiness by carrying out a systematic diagnosis and optimization process. This can help them build a more coherent and robust organic growth agenda that complements their other growth-oriented activities like financial target-setting and identifying growth opportunities. Perhaps more importantly, a focus on growth readiness can enable management teams to approach organic growth as a shared accountability across functional and business-unit boundaries and help them align around the growth agenda.

A focus on growth readiness can enable management teams to approach organic growth as a shared accountability across functional and business-unit boundaries and help them align around the growth agenda.

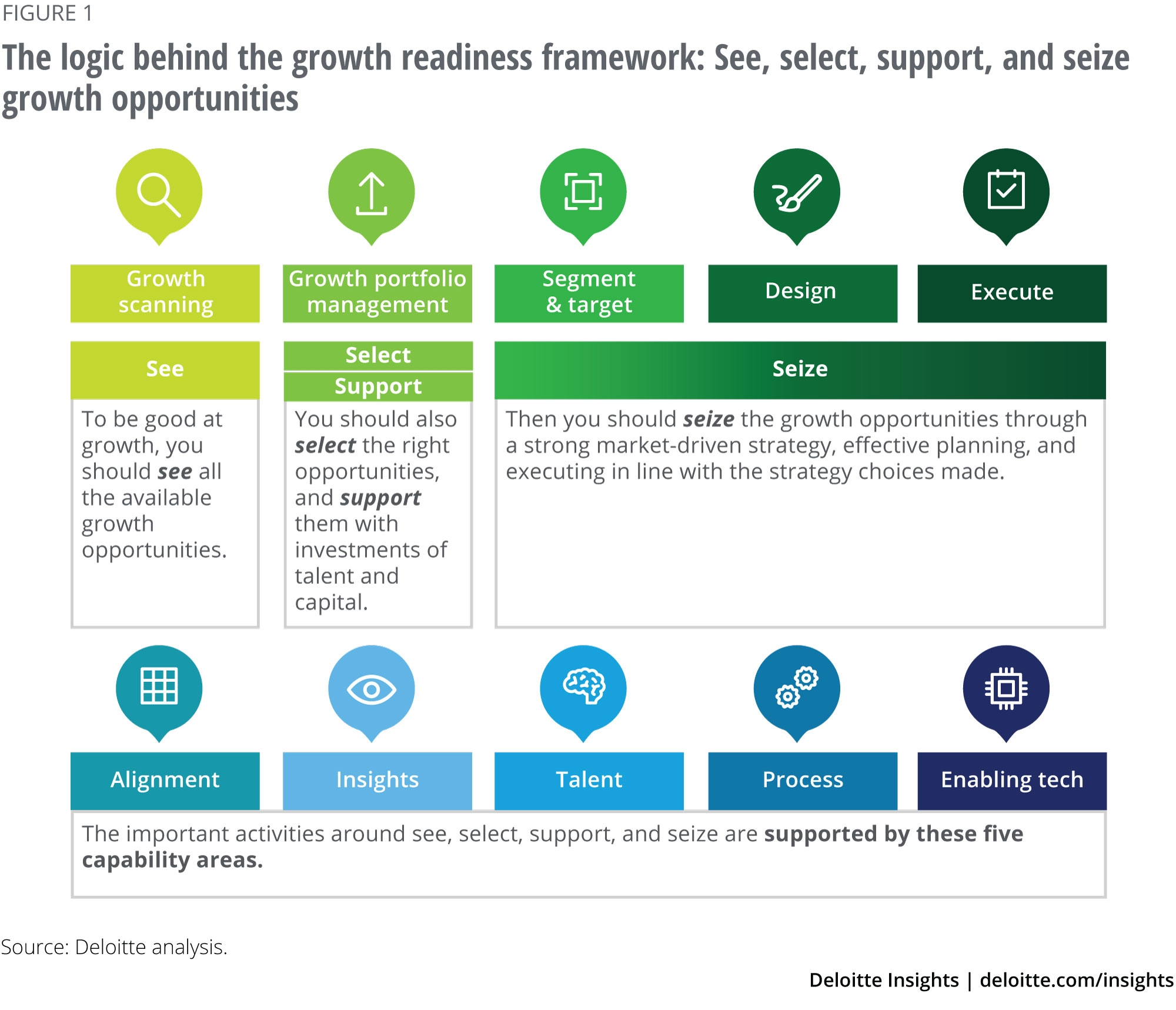

To help companies improve their growth readiness, we posit a growth readiness framework that articulates 10 activity and capability areas essential to organic growth, which we have validated through survey research involving more than 1,200 executives. Covering five activity areas (growth scanning, growth portfolio management, segment and target, design, and execute) and five capability areas (alignment, insights, talent, process, and enabling technology), this framework can provide management teams with a tool to approach the diagnosis of growth readiness in a systematic way. Our research also identified common practices of growth overperformers in each of these 10 areas, offering insights into how management teams might improve the activities and capabilities that drive organic growth (see the sidebar “Our research approach,” for more details on our research methodology and analysis).

In addition to providing guidelines for diagnosis and improvement, we wanted to understand how companies can optimize growth readiness by prioritizing the 10 activity/capability areas. In the process, we discovered two growth archetypes—the see and select archetype and the seize archetype—prevalent among growth overperformers. They represent two distinct ways of winning at organic growth by building strength in different combinations of activities and capabilities across the 10 areas. The choice of growth archetype, as well as an understanding of the activity/capability areas that are important across both archetypes, can help management teams set priorities to improve their growth readiness and kick-start their journey of organic growth.

Our research approach

First, we explored the activities and characteristics of companies that have done well at organic growth (growing above the average rate in their respective industries) as well as those that have struggled to grow (growing below the industry average rate) and came up with a set of observations on the impediments to organic growth. These observations formed the basis for the growth readiness framework. We then stress tested and refined the framework through 25 executive interviews, including those of chief marketing officers (CMOs), chief strategy officers, business division presidents, and other C-level titles.

Second, we translated each of the areas in the growth readiness framework into a series of diagnostic questions designed to assess the respondent’s company’s performance against each.

Third, using the diagnostic questions, we conducted an online research survey of more than 1,200 US-based executives across multiple functions and industries. The survey also asked respondents to self-assess their revenue growth rate relative to their peers over the last three years on a five-point scale, generating growth performance quintiles. This enabled us to compare activity/capability performance with growth performance relative to industry peers.

Then we analyzed the full data set. Here’s what the analysis revealed:

Better performance in any of the growth readiness framework’s 10 activity/capability areas correlates with higher growth relative to a company’s peers. Respondents who had a higher average activity/capability performance fell in a higher growth performance quintile. This was true across an aggregate performance score, as well as within each of the areas. This validated that the activities and capabilities we had included in the framework correlate with growth.

The practices of growth overperformers distinguish them from underperformers. Looking within each activity/capability area, we could identify statistically significant clusters of respondents who had distinctively different practices and see which of these clusters had better or worse growth relative to their peers. This gave us insights into “what good looks like,” and hence potential avenues for improvement in each activity/capability area.

There is more than one way to win at organic growth—we discovered two distinct growth archetypes among growth overperformers. To analyze which of the 10 activity/capability areas are most important to driving growth, we aggregated the top two growth performance quintiles to create a group of growth overperformers. We then came up with two growth archetypes, using cluster analysis to look for statistically significant patterns of strength across the 10 areas, each prioritizing an overlapping but different set of activities and capabilities to drive growth overperformance.

It’s possible to be a growth overperformer even in low-growth industries. Also, the insights gained on organic growth seem to be applicable across all industries and company size categories. We explored variations in responses by industry and company size categories and found growth overperformers in every industry and across low-, medium-, and high-growth industries. Activity/capability performance scores did not differ significantly across company size ranges either. Overperformers exceeded underperformers by about the same margin across all revenue brackets (US$500 million–US$1 billion, US$1 billion–US$5 billion, US$5 billion–US$20 billion, and over US$20 billion).

Growth readiness framework: See, select, support, and seize opportunities

The logic behind the growth readiness framework (figure 1) is intuitive. To be successful at organic growth, a company should:

- See the full set of growth opportunities.

- Select the optimal subset of growth opportunities to pursue.

- Support the selected opportunities by moving talent and investment toward them at speed and scale.

- Seize the growth opportunities through rigorous strategy choices and execution.

From our experience working with many companies on organic growth, we know that organizations frequently struggle across these dimensions. They often have blind spots in how they scan for growth opportunities and may have biases in which opportunities they choose to pursue and which they reject. They may lack the discipline or agility to move resources at speed and scale from the core business to support these opportunities. They may have weaknesses in how they read the market environment; how they make strategic choices about target segments; how they design their value proposition, brand, and customer experience; and how they execute in the field the strategic choices made upstream. They may even lack key underlying capabilities to do so or have incomplete and siloed views of where they stand on them.

Diagnosing growth readiness: The 10 activity/capability areas

Building on our observations from working with companies, we expanded and deepened the activities and capabilities into a growth readiness framework encompassing 10 areas. In the top line (figure 2) are the five “activity” areas that capture the ideas of seeing, selecting, supporting, and seizing the growth opportunities.

Activities

- Growth scanning

- Growth portfolio management

- Segment and target

- Design

- Execute

The bottom line (figure 2) reflects the “capability” areas that can enable the activities in the top line:

Capabilities

- Alignment

- Insights

- Talent

- Process

- Enabling technology

In each of the activity and capability areas, we came up with subcategories. For example, design has subcategories such as customer experience/engagement, optimized offerings/value proposition creation, pricing architecture, and go-to-market/channel strategy. In turn, each of those subcategories was broken down into a series of questions designed to assess performance in various aspects of the activity/capability area in question. For example, in growth scanning, we asked respondents about the dimensions and time frames in which they scan for growth opportunities. In alignment, we asked how strongly the top management team felt shared accountability toward organic growth.

The framework brings together elements that are often looked at in isolation by companies—for example, growth scanning may be seen as the responsibility of the strategy function, while enabling technology is usually the province of IT. By deliberately focusing on activities and capabilities, and not functions, the growth readiness framework can enable management teams to evaluate their growth readiness as a whole through a comprehensive but relatively simple model.

Improving growth readiness: Distinctive practices of overperformers

What does “good” look like in each of the 10 areas of the growth readiness framework? What are the distinctive practices of growth overperformers from which one can learn? How might a management team improve its own company’s performance across the 10 activity and capability areas? Drawing on the 1,200-respondent survey, supplemented by our executive interviews, we distilled a set of insights around the practices that correlate with organic growth overperformance in each of the activity/capability areas.

Growth scanning: Looking for growth opportunities

Correcting for blind spots: Every company has potential biases and blind spots in where it looks for growth. Growth overperformers do a better job of correcting for those, between the core and new businesses, across time horizons, and across types of growth opportunities.

More from the core: While every company looks for growth in adjacent and new businesses, overperformers also look deeper into the core business for growth opportunities—such as growth from increasing retention and loyalty.

Balanced scanning over time horizons: Overperformers balance their attention across time horizons—they are very focused on opportunities within the next two years, and they manage to pay much more attention to opportunities more than five years in the future than underperformers.

More expansive scanning: Overperformers scan more broadly and expansively, for example, actively looking for innovative new business models that might offer growth opportunities.

Growth portfolio management: Selecting and supporting growth opportunities

In-market learning: Growth overperformers incorporate the value of in-market learning into their evaluation of which growth opportunities to pursue more so than underperformers.

Learning across the portfolio: All companies look at a range of financial and strategic aspects of individual growth opportunities. But overperformers also take a portfolio view. They incorporate learnings from previous successful and failed investments; they consider companywide factors such as alignment with the corporate mission and core competencies; and they look at how growth investments impact each other as a portfolio. In other words, they don’t just select individual opportunities, they govern across the growth portfolio.

Resource flexibility: Overperformers can move resources such as talent and capital to growth opportunities faster and at greater scale. Underperformers have budgeting habits or other processes that inhibit moving resources.

Segment and target: Making “where to play” choices

Clear and granular choices based on deeper insight. Growth overperformers make clearer, more decisive choices about targeting, for example, on specific segments to pursue. They also have more fine-grained insights into where and how to target, for example, specific stages of a customer journey or specific customer behaviors to influence. And they have a more detailed understanding of their customers that underpins their segmentation and targeting activities.

Enablement through insights, data, decision processes, and technology. Overperformers enable segmentation and targeting by leveraging complementary strengths in insights and data, decision-making processes, and technology. Collectively, these can ensure that deep and granular customer insights are infused into segmentation and targeting decisions.

Design: Making “how to win” choices

Ingredients of winning value propositions. Growth overperformers excel at the design of brand positioning, customer experience, and pricing. They ensure they have all the key ingredients to consistently develop winning value propositions.

Complementary design-related processes and talent. They deploy complementary underlying processes such as design thinking, rapid prototyping, social listening, and ethnographic research; they also have the talent to operate such processes.

Execute: Delivering “where to play” and “how to win” choices in the field

Execution discipline and alignment: Growth overperformers deliver the customer experience, pricing, and other elements of the strategy in the field as designed through a combination of strong execution discipline and superior alignment between marketing and sales. Underperformers struggle on both fronts.

Closed-loop, real-time adaptation: Overperformers monitor execution elements such as sales channel and campaign performance and adjust/adapt in real time. Underperformers often lack a closed-loop process and struggle to adapt at speed.

Measure execution: Overperformers emphasize measuring the success and failure of growth opportunities more than underperformers. This is in line with their emphasis on in-market learning and learning across the portfolio in growth portfolio management.

Alignment: Acting in a coordinated way across the organization

Shared growth agenda: Overperformers have a shared growth agenda, including shared ambition and aspiration around growth, shared accountability, and a common view of growth priorities across the enterprise. Underperformers, by contrast, report misalignment of incentives and difficulty forging cross-functional alignment.

Personal leadership of alignment: Many growth-driving executives—including CMOs, chief strategy officers, and other C-suite leaders—said in the survey that they personally create and convene forums to ensure alignment around the growth agenda. These leaders also make efforts to sustain alignment by spending more time in person with their C-suite colleagues than a few years ago.

Insights and data: Creating customer and market insights for the business

Data architecture and strategies: Growth overperformance is highly correlated with the breadth and completeness of a company’s data strategies. Several executives outside of the core IT organization report playing key roles in designing data architecture and strategies in their companies.

New revenue streams from data: Growth overperformers are much more likely to be looking to make use of data to drive new revenue streams.

Talent: Managing people and culture

Talent flexibility: Many surveyed executives said access to quality talent is an important growth driver. Overperformers plan for the use of flexible talent by leveraging talent hired by their key partners and leveraging models such as crowdsourcing.

Hiring for growth drivers: Overperformers ensure sufficient hiring and training around growth drivers identified elsewhere in the growth readiness framework, such as data architecture, design thinking, and agile.

Virtuous cycle of growth and talent: Overperformers create a virtuous cycle of growth and talent attraction, in which growth attracts talent and shapes a culture of innovation, which in turn drive growth. They are also associated with advanced human resource policies around diversity, inclusion, and social responsibility, which too contribute to talent attraction and retention.

Process: Deploying effective and efficient ways of working

Test-and-learn approach: Growth overperformers use iterative, test-and-learn, in-market experimentation, and piloting processes. This is consistent with their emphasis on in-market learning in growth portfolio management and on closed-loop, real-time measurement and adaptation in execution.

Agile, cross-functional processes: They are much more likely to be using agile processes and cross-functional ways of working.

Insight-driven decision-making: They also create processes that connect customer and market insights to enable business decisions.

Enabling technology: Providing support to the business

Enabling targeting, personalization, and more through technology. Overperformers use technology to enable other growth drivers—to support granular targeting and personalization, provide their customers with easy access to information, and to leverage predictive analytics for real-time adaptation of execution activities. They also report that their technology platforms are better integrated, allowing them to better exploit their data for growth.

Overperformers can be critical of technology. In the survey, overperformers and companies that are viewed as sophisticated on technology were often critical of their enabling technology capabilities. It appears that overperformers see the potential of technology to help accelerate growth, which makes them more impatient to see it reach its potential in the business.

These distinctive practices of growth overperformers suggest where potential gaps may exist across the activity and capability areas that underlie organic growth. They also point to potential ways in which companies can improve growth readiness in each of the 10 activity/capability areas.

However, a company should not only diagnose growth readiness and explore areas of improvement, but also optimize growth readiness by prioritizing which activity and capability areas it wants to tackle.

Optimizing growth readiness: The two growth archetypes

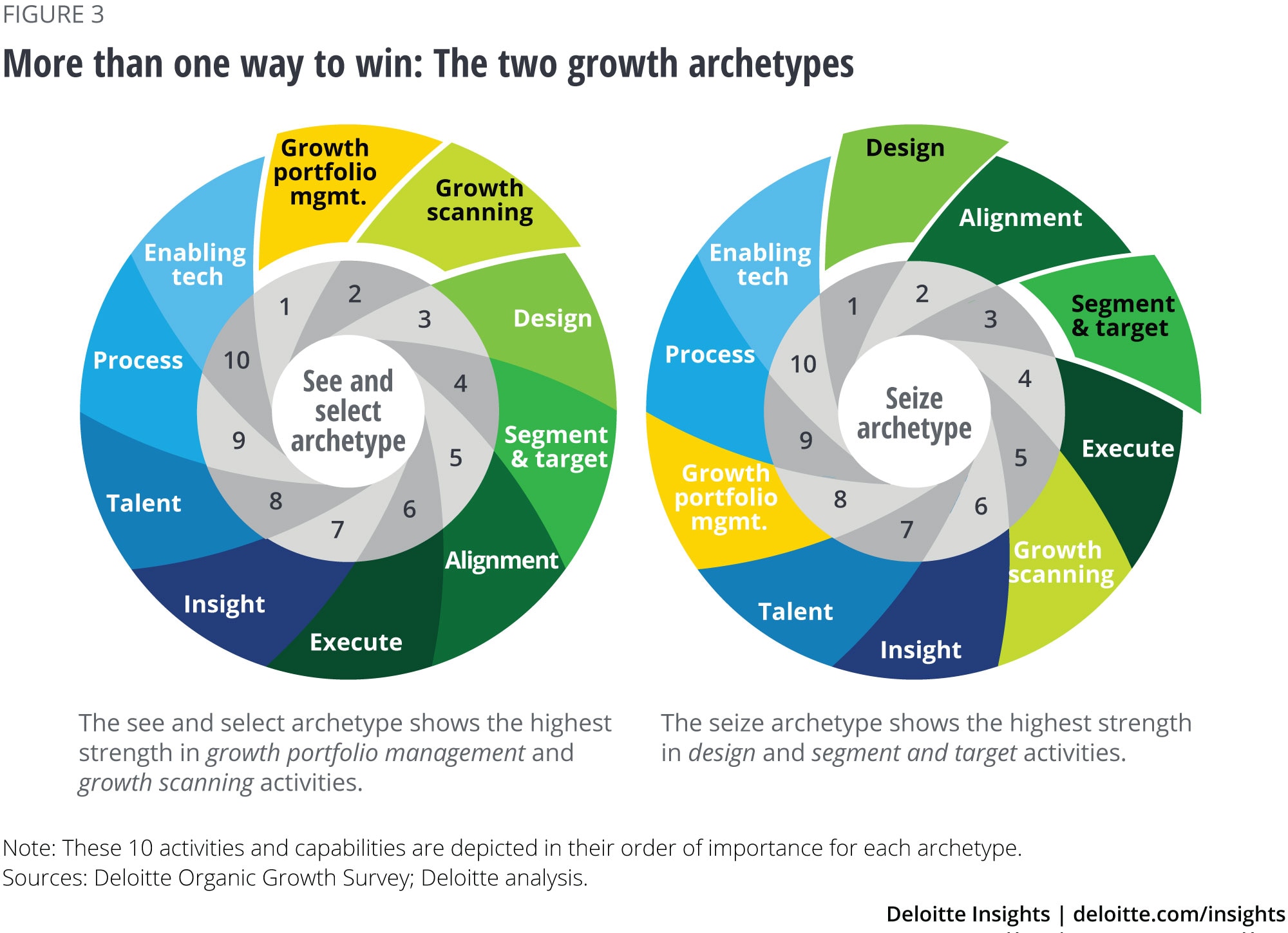

While all of the 10 areas in the growth readiness framework are important—better performance in each of the areas correlates with higher growth—which activities/capabilities matter the most? We found there is more than one way to win at organic growth.

We analyzed growth overperformers to understand if there were, within that group, different patterns of strength across the 10 activity/capability areas. We found two distinct patterns of strength—which we are calling growth archetypes. In other words, there can be two ways to win at organic growth in terms of prioritizing different activity/capability areas.

We found two distinct patterns of strength—which we are calling growth archetypes. In other words, there can be two ways to win at organic growth in terms of prioritizing different activity/capability areas.

While one growth archetype displays the highest strength in growth portfolio management and growth scanning activities, the other shows the highest strength in design and segment and target activities (figure 3). Both archetypes have alignment as the strongest underlying capability. We labeled the growth portfolio management and growth scanning-led archetype as the see and select archetype and the design and segment and target-led model as the seize archetype. The see and select archetype corresponds to the two activities on the top left of the growth readiness framework while seize corresponds to the top right (figure 2).

These archetypes suggest that some growth overperformers do well at organic growth because they see more growth opportunities and select and support them effectively while others do well because they create and execute robust strategies to seize the growth opportunities in front of them.

Which growth archetype works best in which industries?

Under what circumstances and in what industries would each archetype be the most effective? We figured that there is no easy industry split of growth archetypes—all industries have examples of both archetypes, reflecting the unique growth opportunities available to a given company. However, logically speaking, where growth opportunities are far-flung and dynamic, it could be most beneficial to have strength in the scanning and portfolio management disciplines of the see and select archetype. And where growth opportunities are more concentrated and stable, there could be benefit in having strength in the strategy formulation and execution disciplines of the seize archetype.

This view finds validation in the representation of different industries in each of the growth archetypes. While examples of both growth archetypes were visible in all the industries in our sample, there was a marked difference in the representation of individual industries in each archetype:

- Life sciences, hotels/restaurants, and consumer products were substantially overrepresented in the seize archetype while being significantly underrepresented in the see and select archetype.

- Health care, financial services, telecom/media/entertainment, and technology were substantially overrepresented in the see and select archetype, while being significantly underrepresented in the seize archetype.

We observed that the see and select archetype industries are ones in which growth opportunities may be distributed across complex and dynamic ecosystems, so scanning broadly and selecting carefully can be important for growth. In the seize archetype industries, growth opportunities may come from innovating within current and adjacent product categories, so gaining market share through superior strategy and execution may be the key to growth.

Management teams seeking organic growth should consider the location and nature of the growth opportunities available to them while deciding which growth archetype may be appropriate for their company.

Setting growth readiness priorities: What else can you do?

Beyond assessing the nature and location of growth opportunities and figuring out which growth archetype may best fit their situation, management teams should consider a range of other factors while prioritizing activity/capability areas to optimize their growth readiness. Our survey research yielded a set of further insights that suggest potential priorities to consider as well as pitfalls to avoid—such as overrelying on conventional wisdom about organic growth.

The critical capability: Alignment

Both archetypes prioritize alignment. Alignment involves having a shared growth agenda, ambition, and aspiration; having a common view of the enterprisewide growth priorities; and having aligned incentives that can enable organizational collaboration and strategic coordination. The importance of alignment makes intuitive sense, since it can play an enabling role in capturing learning across the portfolio, facilitating the movement of talent and capital to the best growth opportunities while decreasing budget “hoarding,” and identifying activities/capabilities that require enterprisewide investment to improve.

The enabling role of other capabilities

It is the activity in which an underlying capability is used that captures the uplift in performance and not the capability itself—for example, we saw higher ratings for segment and target because technology enabled more granular targeting or personalization. Similarly, design often captured the uplift in performance enabled by a process capability such as rapid prototyping.

Management teams should, therefore, look at both the stand-alone evaluation of the capability and the effectiveness with which it is enabling top-line activities (of the framework). Capabilities that attract poor stand-alone evaluations might, on deeper examination, be supporting superior performance of an enabled activity. Apart from this, we found that the companies that are the most sophisticated in their understanding and use of a given capability are also the most aware of its limitations, the most impatient to see it improve, and the most self-critical of their capabilities.

The table stakes: Design, alignment, and talent/culture

While it is possible, according to our research, to score poorly on certain capabilities such as process and enabling technology and still achieve growth overperformance, there are some activity/capability areas where weaknesses could pose significant roadblocks to growth. None of the growth overperformers had serious weaknesses (i.e., performance scores below 2 out of 5) in the areas of design, alignment, or talent/culture.

This reinforces the importance of design and alignment as seen in the growth archetypes and adds talent/culture to the list. Minimum levels of performance in these three areas can be preconditions of organic growth overperformance and management teams should be concerned if they find severe weaknesses in these areas.

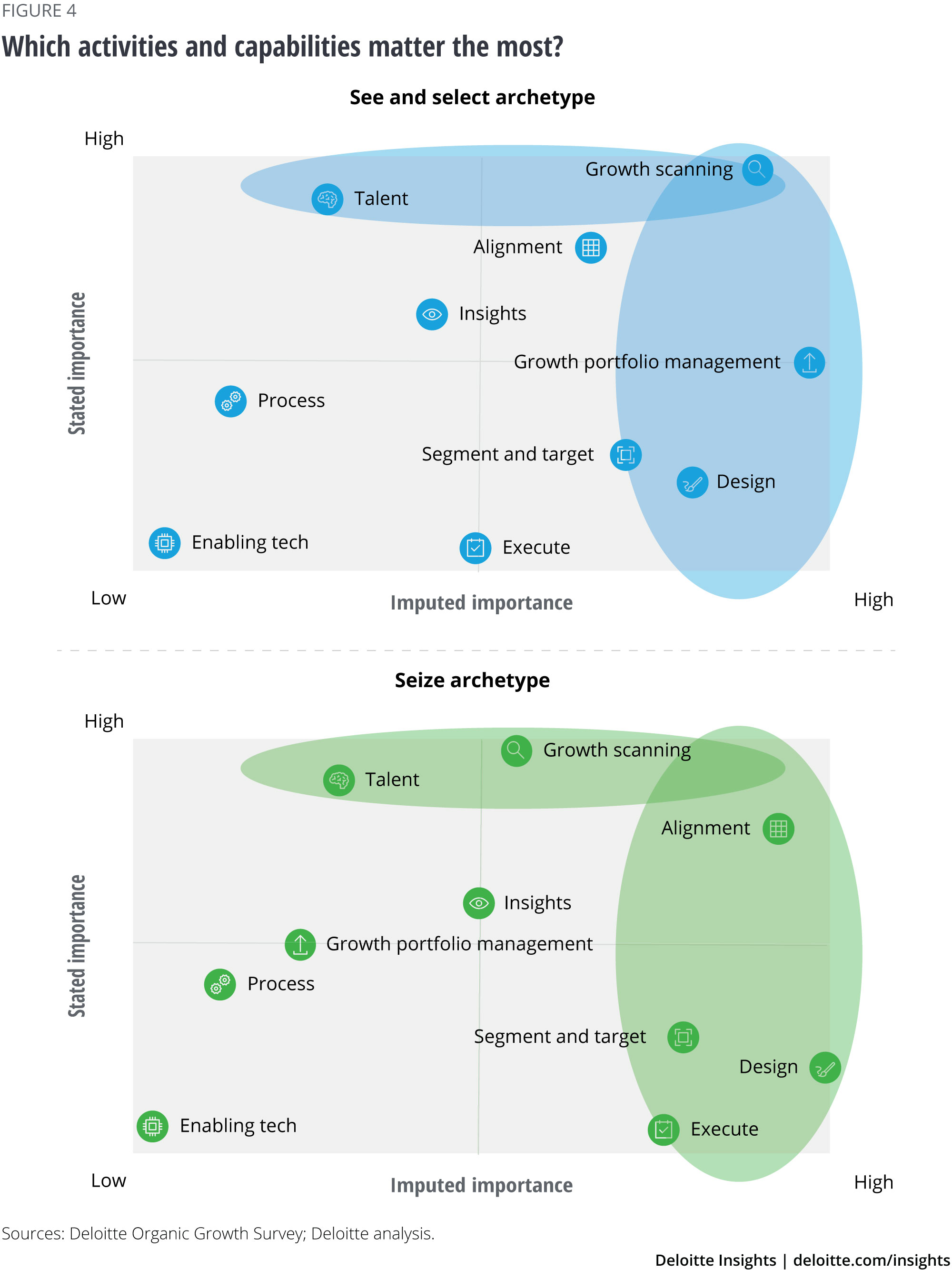

The unexpected importance of segment and target, design, and execute

The three activity areas of segment and target, design, and execute also feature prominently in both growth archetypes and are core to the seize archetype. It’s easy to understand why—they encapsulate the strategy-formulation and execution skills that can be critical to succeeding at organic growth. But surprisingly, they were not initially identified by respondents as the most critical elements for growth. There appeared to be a blind spot there.

Respondents were asked to state which activities/capability areas they thought mattered the most for growth. Figure 4 shows the “stated” importance of each of the 10 activity/capability areas as well as their “imputed” importance (i.e., actual importance based on how each area is prioritized in the growth archetypes.) The bottom right quadrant of each chart represents activity/capability areas that were of low stated importance but high imputed or actual importance—in other words, unexpectedly high importance. Segment/target, design, and execute showed up in that quadrant for both archetypes, which implies that when it comes to organic growth, they can be indispensable and warrant careful diagnosis. Some management teams may be at risk for taking these areas for granted.

The limits of intuition in assessing organic growth readiness

Our survey results threw up even more evidence that some companies have blind spots and biases when it comes to organic growth, and that management teams should be self-aware of the potential limits of their intuition and the validity of conventional wisdom. Respondents named growth scanning and talent as the most important activity and capability areas, respectively. That sounds logical enough—how can you grow if you don’t see the full range of growth opportunities or lack the skilled talent to execute on them?

However, we now know that growth scanning is much more important in one archetype than the other. The intuition about talent, however, was correct—regardless of archetype, none of the growth overperformers in the sample had serious weaknesses in talent/culture (or design or alignment, as described above.) But this was also incomplete: While talent is required, it can be more important to assess the health of the specific activities requiring talent rather than the capability in the abstract.

Beware of the senior management bias

Another source of bias is the seniority of the management making the assessment. Middle management (director/vice president titles) consistently evaluated their activity/capability performance more negatively than senior management (C-suite, board, executive vice president titles). The gap between middle and senior management was 5–6 percent for average and overperformers. However, for underperformers, the gap widened to 13 percent. That is, senior management overestimated their activity/capability performance in companies struggling the most with growth.

The middle management assessments appear to be much more reliable—they track closely with expected performance scores for underperformers, whereas senior management scores for underperformers are closer to what we would expect for average growth performers. Possibly, senior management tends to overestimate the performance of the activities and capabilities because they lead the functions and business units that built them.

The key point is that what holds companies back from organic growth is not just the pattern of strengths and weaknesses across the 10 activity/capability areas. It can also be blind spots and biases of which the management team is unaware, unexamined assumptions about what is most important for organic growth, and the undiagnosed strengths and weaknesses. Assessing growth readiness is a way to uncover those hidden elements and address them systematically to improve organic growth performance.

Companies can be held back from organic growth by blind spots and biases of which the management team is unaware, unexamined assumptions about what is most important for organic growth, and undiagnosed strengths and weaknesses.

Optimizing growth readiness is a team sport

Driving organic growth necessitates businesses to examine the nature and location of growth opportunities and debate archetypes; drive alignment across teams, functions, and levels; evaluate how activities are enabled by their underlying capabilities; challenge intuitive assumptions; and hear from different levels in an organization. No single executive or function is likely to have the perspective required to integrate all the elements. It can require cross-team and cross-functional deliberation and collaboration. Achieving organic growth, therefore, is a team sport.

Management teams seeking to drive organic growth should come together to develop a shared view of the steps required to improve growth readiness. The management team should work through a structured process to diagnose their strengths and weaknesses across the 10 activity/capability areas, to consider how they compare to the practices of growth overperformers, and to set priorities to optimize their efforts across the growth readiness framework. Equipped with a shared understanding of the company’s growth readiness and a growth readiness optimization plan, the management team can then build a more robust growth agenda.

Developing a plan for growth readiness optimization

While the growth readiness optimization plan for a given company will reflect its unique circumstances, there are some rules of thumb for developing such a plan. Here are five factors that management teams should consider:

Start with the knockout risks. Recall that no growth overperformer had serious weaknesses in design, alignment, or talent/culture. Weaknesses in these areas likely represent roadblocks to growth and should be diagnosed and addressed urgently.

Consider which growth archetype best reflects your company’s situation and strategy. Assess not just the current strengths and weaknesses of the activities, but also strategic considerations such as the degree of disruption in current market segments and business models; the scale and nature of already identified growth opportunities; competitive threats; and the company’s in-flight strategy. You may find your organization’s activities and capabilities are misaligned with your future growth strategy needs—for example, a company may have a weakness in growth scanning in an industry prone to disruption and innovation through new business models.

Regardless of growth archetype, work through the activities in the top line of the growth readiness framework from left to right (growth scanning, growth portfolio management, segment and target, design, and execute). While the priority attached to each activity area differs between the growth archetypes, most companies should take the following steps and conduct a diagnosis across all activity areas:

Assess blind spots in growth scanning—many companies have some or the other blind spots, of which they are often unaware. Also, your growth opportunity identification may be biased and may need to be rebalanced across time horizons, among core, adjacent, and new markets, and between current and new business models.

Examine any biases or limitations in how your company prioritizes/selects growth opportunities. For example, are you capturing and applying learning from across the portfolio in selecting growth opportunities?

Explore the flexibility/inflexibility of budget and resource allocation processes in supporting selected growth opportunities. A potential signal of inflexibility is when budgets rarely change year on year and mostly follow a long-term trend regardless of available growth opportunities and their relative priorities.

Diagnose the effectiveness of planning/strategy and execution against growth opportunities.

Assess the health of underlying capabilities, working through the bottom line (alignment, insights, talent, process, and enabling technology) of the growth readiness framework. Explore not only the stand-alone performance of the capabilities but also how far they are enabling and supporting the growth activities in which they are used.

Iterate the steps above to arrive at a shared diagnosis of where growth readiness is falling short across all sections of the growth readiness framework. Then set priorities and a sequence for addressing the weaknesses, reflecting the nature of the growth opportunities available and the most critical activity/capability areas required to exploit them.

Building a robust growth agenda: The three-legged stool

Many companies have historically approached the task of achieving organic growth in two ways—financial target-setting and growth opportunity identification. Often there is a negotiation between those responsible for driving growth from the new opportunities and those setting the financial targets. Eventually, a growth plan is agreed upon in which the new growth opportunities are expected to deliver the financial growth targets.

However, these two mechanisms can be incomplete without a new, third element: Assessing readiness to grow by looking at the performance and health of the activities and capabilities that underpin organic growth.

There are, then, three legs to the “organic growth stool,” not just two. We believe the three-legged stool can provide a much more robust platform on which to build organic growth. Considering only financial targets and growth opportunities without addressing growth readiness across activity/capability areas is likely to lead to underachievement in organic growth. This is often because the undiagnosed blind spots, biases, and weaknesses across the company’s growth-related activities and capabilities act as invisible drags on organic growth performance. If your company has already tried financial target-setting and growth opportunity identification and fallen short on organic growth, conducting a growth readiness assessment may be the first step to diagnosing why.

This is where the growth readiness framework comes in. For management teams seeking to achieve higher organic growth, the framework can provide the basis to diagnose where weaknesses in selected activities and capabilities may be holding the company back from its full growth potential. The findings on distinctive growth practices of overperformers suggest how these activities and capabilities can be improved. The two growth archetypes and other insights can provide guidance on how management teams should set priorities across activity and capability categories and shape them into a growth readiness optimization plan.

You also should build a growth agenda that gets you ready to grow. This agenda should include the three legs of the stool: financial growth targets, growth opportunity identification, and the growth readiness assessment. You should understand not just how much growth you intend to deliver (from financial target-setting), not just where you plan to grow (from growth opportunity identification), but also how you can improve your ability to grow (from growth readiness assessment). The third leg of the stool can help you break out of historical patterns of organic growth performance to reach a new peak.

Such a growth agenda is inherently integrative, crossing multiple functions and involving the entire management team. It often requires alignment and integration of disparate views of the top management team. By expanding the ambit of organic growth to include growth readiness, management teams can formulate a shared growth agenda that positions them to act systematically and collectively to raise their company’s rate of organic growth.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Learn more about strategy and growth

-

Revenue Growth Collection

-

Strategy Collection

-

Consumers in control Infographic7 years ago

-

Digital transformation as a path to growth Article5 years ago

-

Pricing innovation for credit cards Infographic